Abstract

Objective

In recent years, quality of life (QoL) in multiple sclerosis (MS) has been gaining considerable importance in clinical research and practice. Against this backdrop, this systematic review aimed to provide a broad overview of clinical, sociodemographic and psychosocial risk and protective factors for QoL in adults with MS and analyse psychological interventions for improving QoL.

Method

The literature search was conducted in the Scopus, Web of Science and ProQuest electronic databases. Document type was limited to articles written in English, published from January 1, 2014, to January 31, 2019. Information from the selected articles was extracted using a coding sheet and then qualitatively synthesised.

Results

The search identified 4886 records. After duplicate removal and screening, 106 articles met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for qualitative synthesis and were assessed for study quality. Disability, fatigue, depression, cognitive impairment and unemployment were consistently identified as QoL risk factors, whereas higher self-esteem, self-efficacy, resilience and social support proved to be protective. The review analysed a wide spectrum of approaches for QoL psychological intervention, such as mindfulness, cognitive behavioural therapy, self-help groups and self-management. The majority of interventions were successful in improving various aspects of QoL.

Conclusion

Adequate biopsychosocial assessment is of vital importance to treat risk and promote protective factors to improve QoL in patients with MS in general care practice.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, mental health, adult neurology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review of risk factors and psychological intervention for quality of life in multiple sclerosis for over a decade.

A comprehensive and robust search strategy and strict inclusion criteria were employed to cover all the relevant evidence.

Careful standardised risk of bias was assessed in all 106 studies included.

Due to heterogeneity of the studies, only qualitative synthesis of results was possible.

The huge number of publications made it necessary to limit the time span to the 5-year period from January 1, 2014, to January 31, 2019.

Introduction

The Constitution of the WHO declares health to be ‘…a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’.1 Quality of life (QoL) is a multidimensional concept that encompasses the domains included in this definition of health.2 3 Its introduction in medical literature dates back to 1960,4 with its importance continuously growing to date.5

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurodegenerative condition characterised by a wide range of symptoms and a highly unpredictable prognosis, which can severely affect patient QoL.6–8 Patients with MS tend to report lower QoL than the general population.9–12 This diminished QoL may be due to their impaired functioning in daily living, more so if the help of caregivers is required, impeding family relations, work and social dynamics.13 14 The impact of MS on QoL can be affected by numerous disease-related factors, such as disability level or MS type, and individual factors such as social support, education, age or employment.15–18

Identification of risk and protective factors is a key point in implementing strategies to improve patient’s QoL.7 In this context, all influences must be considered to contribute to QoL in MS.7 19 In addition to providing practitioners with useful information on the impact of symptoms and therapy on the patient’s life, QoL is also an indicator of treatment success and a predictor of disease progression.20–22

In view of its relevance in healthcare research, the need to compile and condense available scientific evidence on the subject is urgent. Against this backdrop, this systematic review gives a comprehensive overview of risk and protective factors related to QoL in MS as well as relevant psychological interventions. The growing number of studies on this subject2 22 provides a vast amount of data, which due to the inconsistency of findings needs careful assessment to come to evidence-based conclusions.

Methodology

This systematic review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.23 As a review of prior publications, ethical approval (or informed consent) was unnecessary. A review protocol is available from the corresponding author on request.

Search strategy

The systematic search focused on journal articles published between January 1, 2014, and January 31, 2019. The Scopus, Web of Science and ProQuest databases were searched in February and March 2019. The key words used were (‘multiple sclerosis’) AND (‘quality of life’ OR ‘health-related quality of life’ OR ‘well-being’ OR ‘well-being’ OR ‘life satisfaction’). The search terms were intentionally broad to ensure wide coverage of the literature. The search field was limited to ‘title/abstract’ and language was limited to ‘English’. The complete research string is reported under online supplemental file 1.

bmjopen-2020-041249supp001.pdf (112.7KB, pdf)

There is no published systematic review on this topic in the Cochrane Library.

Study selection

First, title and abstract were screened to identify suitable articles for full text review. The screening process was performed independently by two researchers. Any disagreement about study selection was resolved by consensus with a third reviewer.

Inclusion criteria were the following:

Studies primarily focusing on QoL determinants and psychological intervention to improve it.

Study participants aged over 18 years with a confirmed MS diagnosis.

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

Non-psychological intervention.

Not primary research studies (systematic reviews, meta-analyses, protocols and clinical guidelines were excluded).

Studies on the development and validation of QoL measurement instruments.

QoL risk or intervention studies for healthy behaviour, cognitive rehabilitation, physical activity or pharmacological treatment.

Studies on comorbidity with another illness or mental health diagnosis.

Sample selection based on a special condition (eg, only employees or patients with MS under certain pharmacological treatment).

Studies not using a validated QoL measurement tool.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the studies was appraised with a well-established standardised 12-item checklist,24 in which every item represents a methodological feature: inclusion/exclusion criteria, methodology/design, attrition rate, attrition between-groups, exclusions after, follow-up, occasion of measurements, pre/post measures, dependent variables, control techniques, construct definition and imputing missing data. The codification criteria proposed by the checklist authors was used. No article was excluded from quality appraisal.

Data abstraction

Data were extracted from selected articles based on a previously designed coding sheet. The pilot study was approved by consensus. The information extracted included: title, authors and publication year, country (city), design, sample characteristics, study variables and measurement tools, main results and conclusions. After extraction, the information was independently reviewed by two authors to avoid errors or omitting data.

A meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes, so a narrative synthesis was undertaken.

Results

Literature screening

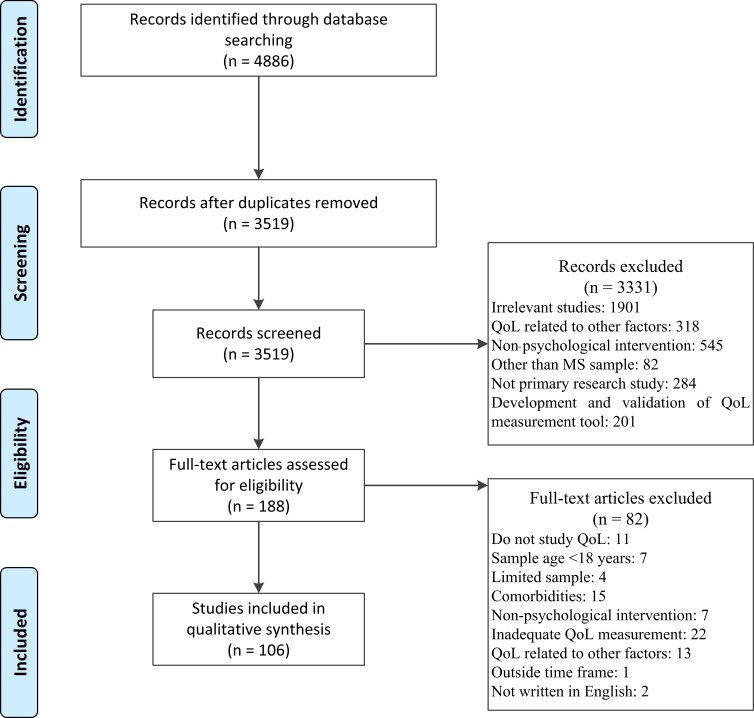

A total of 4886 articles were initially identified from Scopus, Web of Science and ProQuest. After removal of duplicates and abstract analysis, 188 studies were eligible for full text review. Finally, 106 were selected for the narrative analysis. The selection process is detailed below in a PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of selection process. MS, multiple sclerosis; QoL, quality of life.

Methodological quality

Methodological quality scores using the 12-item checklist are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Methodological quality of articles (n=106)

| Inclusion criteria | Design | Attrition | Attrition between groups | Exclusion after | Follow-up period | Occasion of measurement | Same pre–post measurement | Normalisation of DV measurement | Control techniques | Construct definition | Imputing missing data | |||||||||||

| Yes | No or N/A* | Pre-experimental | Quasi experimental | Experimental | Yes | No or N/A* | Yes | No or N/A* | Yes | No or N/A* | Yes | No or N/A* | One | Two or more | Yes | No or N/A* |

Yes | No or N/A* | Yes | No or N/A* | ||

| 99 | 1 | 7.7 | 33.7 | 58.7 | 48.1 | 51.9 | 28.9 | 62.9 | 22.1 | 77.9 | 32.7 | 67.3 | 70.2 | 29.8 | 70.2 | 29.8 | 100 | 70.2 | 29.8 | 100 | 19.2 | 80.8 |

*No or N/A=the item is not proceeded or does not appear.

Study characteristics

The articles included were analysed by their primary and secondary outcomes. Seventy studies analysed QoL risk and protective factors (table 2), 11 focused on the development of QoL at different ages and times in the disease (table 3) and 25 studied the effect of psychological intervention on QoL in MS (table 4).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included articles

| Authors, publication year |

Study design | Quality of life measurement | Sample size (N) Age (mean) Sex (female%) |

Main results | |

| Risk factors | Protective factors | ||||

| Clinical variables | |||||

| Gupta et al (2014)25 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) | N=74 451 47.9 years 51.3% |

EDSS (PCS) | |

| Gross et al (2017)36 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=810 RRMS 48.9 years SPMS 55.7 years RRMS 71.6% SPMS 56.2% |

Progressive MS type (PCS) | |

| Zhang et al (2019)38 | Cross-sectional | EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) | N=1958 55.3 years 78.1% |

Progressive MS type onset | |

| Rezapour et al (2017)26 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=171 35.7 years 76.6% |

Relapses in the last 3 months | Mild EDSS RRMS type |

| Marck et al (2017)56 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=2296 45.5 years 82.2% |

Pain | |

| Milinis et al (2016)57 | Cross- sectional | Leeds MS Quality of Life Scale (MSQoL) | N=701 48.8 years 72% |

Spasticity | |

| Zettl et al (2014)58 | Cross- sectional | EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) |

N=414 48.6 years 64.3% |

Spasticity | |

| Leonavicius et al (2016)42 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=137 44.7 years 72.3% |

Fatigue (MCS) | |

| Garg et al (2016)43 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=89 54.26 years 66% |

Fatigue | |

| Fernández-Muñoz et al (2015)44 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=108 44 years 55% |

Fatigue | |

| Weiland et al (2015)45 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=2738 45.5 years 82.3% |

Fatigue | |

| Aygünoğlu et al (2015)46 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=120 34.24 years 70% |

Fatigue | |

| Vister et al (2015)47 | Cross- sectional | WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) 2.0 | N=210 50.8 years 72.4% |

Fatigue | |

| Tabrizi et al (2015)48 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=217 36.2 years 79% |

Fatigue Poor sleep quality Low MCS (PCS) |

|

| White et al (2019)64 | Cross- sectional | EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) | N=531 51.60 years 70.1% |

Sleep disorder | |

| Barin et al (2018)49 | Cross- sectional | EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) |

N=855 48 years 72.7% |

Fatigue Balance Spasticity Paralysis Walking difficulties |

|

| Kratz et al (2016)50 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=180 50.5 years 78% |

Fatigue (MCS) Pain (MCS) Memory loss (MCS) |

|

| Colbeck et al (2018)53 | Cross- sectional | RAND-36 Health Item Survey (RAND-36) | N=30 – 73.33% |

Cognitive fatigue Low sensory sensitivity Sensation avoiding |

|

| Grech et al (2015)65 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=107 48.8 years 77.6% |

Cognitive inflexibility | |

| Sgaramella et al (2014)68 | Cross- sectional | Quality of life questionnaire (QoL) | N=39 42.2 years 71.8% |

Executive function | |

| Khalaf et al (2016)59 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=1048 47.8 years 81% |

Lower urinary tract symptoms | |

| Vitkova et al (2014)60 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=223 38.4 years 67.3% |

Bladder dysfunction (PCS) Sexual dysfunction (MCS) |

|

| Qaderi et al (2014)61 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=132 36.9 years 100% |

Sexual problems (PCS and MCS) |

|

| Schairer et al (2014)62 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) | N=6138 50.6 years 74.7% |

Sexual dysfunction | |

| Ma et al (2017)63 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) | N=231 40.2 years 58.4% |

Sleep disorders | |

| Psychosocial variables | |||||

| Hernández-Ledesma et al (2018)71 | Cross- sectional | WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQoL-BREF) | N=26 39.2 years 57.5% |

Problem avoidance Social withdrawal Wishful thinking Self-criticism Anxiety Depression |

Problem resolution Cognitive restructuring Emotional social and instrumental support Emotional expression |

| Grech et al (2018)80 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=107 48.8 years 77.57% |

Behavioural disengagement Suppression and self-control Emotional venting |

Acceptance Growth Restrain |

| Zengin et al (2017)79 | Cross- sectional | WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQoL-BREF) | N=214 36–46 years 53.2% |

Self-distraction Denial Substance use |

Planning Active coping Acceptance Positive reinterpretation Social support |

| Farran et al (2016)81 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life Questionnaire (MusiQoL) | N=34 36 years 56% |

Self-criticism Escape avoidance Distancing Self-controlling |

Emotional social support Instrumental social support Planful problem solving Positive reappraisal |

| Mikula et al (2014)82 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=113 40.8 years 77% |

Problem focused coping Stopping unpleasant emotion Getting support |

|

| Van Damme et al (2016)85 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=117 41 years 70.2% |

Acceptance (PCS and MCS) tenacious goal pursuit (PCS) flexible goal adjustment (MCS) |

|

| Wilski et al (2016)88 | Cross- sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) | N=257 47.9 years 69.93% |

Self-efficacy Self-esteem Illness identity |

|

| Nery-Hurwit et al (2018)86 | Cross- sectional | Function Neutral Health-Related Quality of Life Short Form (FuNHRQoL-SF) | N=259 48.6 years 84.23% |

Resilience Self-compassion |

|

| Calandri et al (2018)89 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) | N=90 37 years 61.1% |

Sense of coherence | |

| Fernández-Muñoz et al (2018)75 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=108 44 years 55% |

Depression | |

| Pham et al (2018)76 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) | N=310 49 years 73.6% |

Anxiety | |

| Prisnie et al (2018)72 | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=2 weeks later) | Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) | N=139 40 years 70.5% |

Anxiety Depression |

|

| Alsaadi et al (2018)73 | Cross- sectional | WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQoL-BREF) | N=80 35.1 years 65% |

Anxiety Depression |

|

| Labiano-Fontcuberta et al (2015)74 | Cross- sectional | Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis (FAMS) | N=157 41.7 years 66.9% |

Depression Anxiety Anger expression-in |

|

| Paziuc et al (2018)69 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=60 46 years 85% |

Trait anxiety State anxiety Depression |

Extraversion Emotional Stability |

| Phillips et al (2014)70 | Cross-seccional | WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQoL-BREF) | N=32 44.0 years 75% |

Emotional problems | |

| Salhofer-Polanyi et al (2018)77 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=139 40.0 years 70.5% |

Depressive temperament Cyclothymic temperament |

Hyperthymic temperament |

| Demirci et al (2017)78 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=74 35.3 years 65.51% |

Type D personality | |

| Mikula et al (2015)93 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=116 40.4 years 72.4% |

Social participation (MCS y PCS) | |

| Costa et al (2017)92 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=150 41.7 years 70.7% |

Social support | |

| Nakazawa et al (2018)27 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=63 41.7 years 66.67% |

EDSS level | Resilience |

| Ciampi et al (2018)28 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) | N=43 57.2 years 65.1% |

EDSS level Fatigue Depression |

|

| Fernández-Jiménez et al (2015)32 | Cross-sectional | Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis (FAMS) | N=97 47.3 years 82.5% |

EDSS level Depression |

|

| Klevan et al (2014)29 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=93 41.8 years 69% |

EDSS (PCS) Fatigue Depression Apathy |

|

| Williams et al (2014)55 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) |

N=447 49.3 years 70.02% |

Pain (PCS) Muscle spasms (PCS) Stiffness (PCS) Depression (MCS) |

|

| Hyncicova et al (2018)40 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=67 32.3 years 53.7% |

Number and severity of symptoms Fatigue Stress Depression Anxiety |

|

| Shahrbanian et al (2015)39 | Cross- sectional | Person Generated Index (PGI) | N=188 43 years 74% |

Pain Fatigue Irritability Anxiety Depression Sleep disorder Cognitive deficit |

|

| Strober et al (2018)51 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=69 40.4 years 89.5% |

Pain Fatigue Behavioural disengagement Denial Depression Anxiety High neuroticism Low extroversion Low self-efficacy |

Acceptance Growth Emotional social and instrumental support Planning Active coping Positive reinterpretation Humour |

| Dymecka et al (2018)52 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) | N=137 46.5 years 53.3% |

Fatigue Upper limb disability Lower limb disability Cognitive disorders Emotional problems |

|

| Samartzis et al (2014)66 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=100 40.5 years 64% |

Perceived planning/organisation dysfunction Perceived retrospective memory dysfunction Depression |

|

| Brola et al (2016)31 | Cross-sectional | EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) |

N=2385 37.8 years 69.7% |

EDSS level MS duration Lack of DMD treatment Age |

|

| Brola et al (2017)30 | Cross-sectional | EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) |

N=765 44.9 years 67.7% |

EDSS MS duration Be unemployed Age No immunomodulatory therapy |

|

| Abdullah et al (2018)54 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=200 35.1 years 68% |

Motor symptoms Low resistance Sensory symptoms Low income Be unemployed |

|

| Nickel et al (2018)33 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (MusiQoL) | N=1220 47.8 years 76% |

EDSS Comorbidity |

High educational level High employment status |

| Campbell et al (2017)67 | Cross-sectional | Functional assessment of multiple sclerosis (FAMS) EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) |

N=62 49.4 years 69.35% |

Cognitive deficit Be unemployed |

|

| Chiu et al (2015)94 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) | N=157 43.8 years 86% |

Be unemployed | Disability adjusted employment |

| Boogar et al (2018)35 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) | N=193 38.1 years 64.8% |

High disability Depression Low socioeconomic status |

Positive story treatment |

| Bishop et al (2015)41 | Cross-sectional | Quality of Life Scale (QoLS) | N=1839 54 years 78.1% |

Number and severity of symptoms Perceived stress |

High educational level High employment status Job satisfaction Job match |

| Cioncoloni et al (2014)34 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=57 41.7 years 68.42% |

EDSS level Fatigue Pain Bladder dysfunction Bowel dysfunction Depressive manifestations Sleeping problems Introverted personality Be unemployed |

|

| Cichy et al (2016)37 | Cross-sectional | Quality of Life Scale (QoLS) | N=703 63 years 76% |

Progressive MS Progressive diagnosis Number and severity of symptoms Perceived stress Be male Not married/not living with significant other Unable to meet living expenses |

|

| Mediational variables | Mediator variable | Mediated relation | |||

| Mikula et al (2018)84 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=156 40 years 75% |

Coping strategies Problem focused Emotional focused Stopping |

Personality type D and MCS |

| Mikula et al (2015)83 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=154 40.05 years 76% |

Coping strategies | Fatigue and MCS and PCS |

| Mikula et al (2017)90 | Cross- sectional | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=74 35.3 years 65.51% |

Self-esteem | Social participation and MCS |

| Koelmel et al (2017)87 | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=10 weeks later/T3=26 weeks later/T4=52 weeks later) | Short Form Health Survey 8 (SF-8) | N=163 52.2 years 87.1% |

Resilience | Social support and MCS |

| Valvano et al (2016)91 | Cross- sectional | Leeds MS Quality of Life Scale (MSQoL) | N=128 45.5 years 85% |

Cognitive fusion | Stigma and QoL |

DMD, disease modifying drug; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; MCS, Mental Composite Score; MS, multiple sclerosis; PCS, physical composite; QoL, quality of life; RRMS, remittent remitting; SPMS, secondary progressive.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies

| Authors, publication year | Study design (T1: /T2:…) | Quality of life measurement | Sample size (N) Age (median) Sex (female%) |

Main results |

| Years of diagnosis | ||||

| Possa et al (2017)95 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N=38 32.9 years 58% |

Decrease in MCS (38%) and PCS (19%) in the first year after diagnosis. |

| Calandri et al (2017)97 | Cross-sectional | Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) | N=102 35.8 years 61.8% |

Problem solving (β=0.28) and avoidance (β=0.25) was related to a higher MCS in the first 3 years of diagnosis. |

| Nourbakhsh et al (2016)98 | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=3 months after diagnosis/T3=6 months after diagnosis/T4=12 months after diagnosis/T5=18 months after diagnosis/T6=24 months after diagnosis/T6=36 months after diagnosis) | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=43 36 years 72% |

Baseline severity of fatigue and depression predicts PCS and cognitive function and fatigue MCS in the first 3 years of diagnosis. |

| MS progression | ||||

| Kinkel et al (2015)100 | Longitudinal (T1=CIS diagnosis/T2=5 years after diagnosis/T3=10 years after diagnosis) | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory (MSQLI) | N=127 34.1 years 74% |

A second clinic event consistent with CDMS, higher EDSS at the diagnosis and an earlier onset CDMS predicts a decrease in PCS. |

| Bueno et al (2014)101 | Cross-sectional (25–30 years after diagnosis) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N=61 54.9 years 83.6% |

Patient changing from benign (EDSS<3) to non-benign (EDSS>3) decreases PCS. |

| Years of MS duration | ||||

| Baumstarck et al (2015)102 | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=24 months later) | Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life questionnaire (MusiQol) Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=526 40.0 years 74.3% |

Low levels of QoL, higher MS duration and higher EDSS level at T1 predicted worse QoL at T2. |

| Tepavcevic et al (2014)103 | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=3 years later/T3=6 years later) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N=93 41.5 years 71% |

Higher EDSS and depression at basal level predicted a decrease of QoL at T1 and T2. |

| Young et al (2017)105 | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=7 years later/T3=10 years later) | Assessment of Quality of life (AQoL) | N=70 59.8 years 71.6% |

Higher pain predicts a decrease in QoL. |

| Chruzander et al (2014)104 | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=10 years later) | EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) | N=118 49 years 72% |

Cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms and EDSS predicted a decrease in QoL at T2. |

| Group age | ||||

| Stern et al (2018)96 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N=57 50 years 73.7% |

The youngest group (35–44) presents worst PCS vs the oldest (55–65). |

| Buhse et al (2014)99 | Cross-sectional | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life–54 (MSQoL-54) | N=211 65.5 years 80% |

Risk of neurologic impairment, physical disability, depression and the comorbidity of thyroid disease was associated with decrease in PCS. Being widowed and employed was associated with increase in PCS. |

CDMS, clinical defined multiple sclerosis; CIS, clinical isolated syndrome; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; MCS, Mental Composite Score; MS, multiple sclerosis; PCS, Physical Composite Score; QoL, quality of life.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the included articles

| Authors, publication year |

Programme name | Study design | Quality of life measurement | Sample size (N) Age (median) Sex (female%) |

Main results |

| Mindfulness-based therapies | |||||

| Carletto et al (2017)106 | Body-affective mindfulness (BAM) | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=post-treatment/T3=6 months later) | Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis (FAMS) | N=45 44.1 years 71.1% |

Increase in general score FAMS from T1 to T2 (p<0.001) and from T2 to T3 (p=1). |

| Besharat et al (2017)107 | Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment) | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N intervention/control=12/11 35 years 100% |

Increase in general QoL score in the intervention group (p<0.05). |

| Blankespoor et al (2017)108 | Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N=25 52.6 years 84% |

Increase PCS (p<0.001). |

| Simpson et al (2017)109 | Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment/T3=3 months later) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory (MSQLI) | N=25 43.6 years 92% |

Small and insignificant increase QoL from T1 to T2 (p=0.48) and insignificant increase from T2 to T3 (p=0.71). |

| Spitzer et al (2018)110 | Community-based group mindfulness | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment/T3=8 weeks later) | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=23 48.4 years 91.3% |

Increase MCS from T1 to T2 (p=0.008). |

| Ghodspour et al (2018)111 | Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N intervention/control=15/15 36 years 100% |

Increase in health distress (p=0.032), mental well-being (p=0.001), role limitation due to emotional problems (p=0.005) and cognitive performance (p=0.04) subscales. |

| Cognitive behavioural | |||||

| Case et al (2018)112 | Trial of healing light guided imagery (HLGI) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N intervention/control=9/8 49.1 years – |

Increase in PCS (p=0.01) and MCS (p<0.01) in the intervention group. |

| Blair et al (2017)113 | Dialectical Behaviour Group Therapy (TCD) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment/T3=6 months later) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N intervention/control=10/10 40.4 years 90% |

Increase in MSQoL-54 from T1 to T3 (p=0.01). |

| Calandri et al (2017)114 | Group-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=6 month post-treatment/T3=1 year post-treatment) | Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) | N intervention/control=54/31 38 years 61% |

Increase in MCS T2 in the CBT group vs control (p=0.036). Increase in MCS T3 in the CBT group vs control (p=0.049). |

| Graziano et al (2014)115 | Group-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment/T3=6 months later) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N intervention/control=41/41 42.3 years 66% |

Increase in MSQoL-54 at T3 in the CBT group vs control group (p<0.05). |

| Kiropoulos et al (2016)116 | Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for depressive symptoms | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment/T3=20 weeks later) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N intervention/control=15/15 34.6 years 86.7% |

Differences between control and CBT group MCS and PCS in T2 and T3 (p<0.001). |

| Chruzander et al (2016)117 | Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) focused on depressive symptoms | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=3 weeks post-treatment/T3=3 months post-treatment) | Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) |

N=15 38 years 80% |

Improvement in QoL from MSIS-29 and EQ-5D in T2 and T3 (p<0.05). |

| Kikuchi et al (2019)118 | Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) on depression | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=mind-treatment/T3=post-treatment) | Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis (FAMS) | N=7 46.1 years 71.4% |

Positive but not significant increase in FAMS (p>0.05). |

| Pakenham et al (2018)119 | Resilience Training Programme (ACT) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment/T3=3 months later) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N=37 39.4 years 73% |

Increase in PCS (p<0.001) and MCS (p<0.006) from T1 to T2, maintained at T3, without significant changes. |

| Proctor et al (2018)120 | Telephone-supported acceptance and commitment bibliotherapy (ACT) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-randomisation/T2=12 weeks after randomisation) | EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) | N intervention/control=14/13 45.8 years 78% |

No significant increase in QoL (p=0.62). |

| Social and group support | |||||

| Liu (2017)125 | Hope-Based Group Therapy (HBGT) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment) | Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) | N intervention/control=18/14 35.1 years 100% |

Physical and psychological QoL increase in HBT group (p<0.05). |

| Abolghasemi et al (2016)121 | Supportive–Expressive Therapy (SE) | Longitudinal (T1=pre-treatment/T2=post-treatment | WHO Quality of Life questionnaire (WHOQoL-BREF) | N intervention/control=16/16 31.8 years 41.7% |

Increase QoL from T1 to T2 (p<0.001). |

| Jongen et al (2016)123 | Intensive social cognitive treatment (can do treatment) with participation of support partners | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=12 months post-treatment) | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N=38 – 65.8% |

PCS increase (p=0.032) and MCS (p=0.087) in the RR group. |

| Jongen et al (2014)122 | Intensive social cognitive wellness programme with participation of support partners | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=1 months post-treatment/T3=3 months post-treatment T4=6 months post-treatment | Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Instrument (MSQoL-54) | N=44 45.7 years 79.5% |

MCS increase at T2, T3 and T4 and PCS at T4 (p<0.05). |

| Eliášová et al (2015)124 | Self-Help group (SH) | Cross-sectional (T1=after the treatment) | WHO Quality of Life questionnaire (WHOQoL-BREF) | N intervention/control=46/35 42.2 years 59% |

Increase in physical (p<0.001), psychological (p<0.001) and social relationships (p<0.001) in the SH group. |

| Symptom and self-management-based therapies | |||||

| Mulligan et al (2016)126 | Fatigue self-management programme ‘Minimise Fatigue, Maximise Life: Creating Balance with Multiple Sclerosis (MFML)’ | Longitudinal (T1=1 month pre-treatment/T2=pre-treatment/T3=post-treatment). | Short Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12) | N=24 49.3 years 100% |

Positive but not significant changes in SF-12 (p>0.05). |

| Thomas et al (2014)127 | Group-based fatigue management (FACETS) | Longitudinal (T1=1 week before treatment/T2=1 month post-treatment/T3=4 month post-treatment/T4=12 month post-treatment) | Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) |

N intervention/control=84/80 48 years 73% |

Changes in physical health MSIS-29 (p=0.046) and vitality SF-36 (p=0.03) at T4. |

| Ehde et al (2015)128 | Telephone-Delivered Self-Management (SM) | Longitudinal (T1=before group randomisation/T2=post-treatment/T3=6 month post-treatment/T4=12 month post-treatment) | Short Form Health Survey 8 (SF-8) | N intervention/control=75/88 51 years 89.3% |

MCS and PCS increase at T2, T3 and T4 (p<0.05). |

| Feicke et al (2014)129 | Education programme for self-management competencies (S.MS) | Longitudinal (T1=1 basal level/T2=post-treatment/T3=6 month post-treatment) | Hamburg quality of life questionnaire in multiple sclerosis (Sclerosis Quality) | N intervention/control=31/33 41.9 years 87.1% |

Stable positive changes in QoL (p=0.007). |

| Other psychological intervention | |||||

| LeClaire et al (2018)130 | Group Positive Psychology | Longitudinal (T1=basal level/T2=post-treatment) | Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | N=11 53.5 years 100% |

Increase in SF-36 vitality subscale score (p=0.016). Increase in mental health SF-36 subscale (p=0.098) that did not reach statistical significance. |

HBT, hope-based group therapy; MCS, mental component score; PCS, physical component score; QoL, quality of life; RR, relapsing–remitting.

All the articles included employed standardised and validated QoL measurement instruments; 64 studies evaluated QoL with a generic measure and 50 studies made use of a disease-specific measure. The Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) was mainly used (n=29) as a generic measure and Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) (n=28) as a disease-specific measure. Finally, 11 studies used more than one measure to evaluate QoL. The study designs were mostly cross-sectional (n=74), and sample sizes ranged from 7 to 74 451 participants.

The main findings of the articles are summarised below.

Risk and protective MS QoL factors

Factors influencing MS patient’s QoL are summarised in table 2.

Clinical factors

Functional impairment as assessed by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) level was one of the leading causes of diminished QoL.25–35 Disease duration,30 31 progressive type,26 36 37 progressive MS onset38 and relapses in the last 3 months were further relevant factors negatively affecting QoL.26

Several studies found a significant association between the severity and number of symptoms and the decline of QoL in MS.33 37–41 Fatigue was identified as a main risk factor.28 29 39 40 42–52

A number of articles stated the importance of sensory53 54 and motor49 52 54 55 dysfunction on QoL, including paralysis, walking difficulties, balance, stiffness and spasms as motor problems, specifically emphasising pain34 39 50 51 55 56 and spasticity,49 57 58 and low sensory sensitivity and sensation avoidance as sensory problems.

Bladder dysfunction,34 59 60 bowel dysfunction,34 sexual,60–62 and sleeping34 39 48 63 64 problems contributed to deterioration of QoL.

A diversity of cognitive impairments, for instance, cognitive fatigue, memory loss and planning/organisational dysfunction, were recognised as risk factors by a number of studies.39 50 52 53 65–67 Sgaramella et al68 showed that maintaining executive functioning was a protective factor of QoL. This was also the only study on the important subject of cognitive reserve and QoL.

Psychosocial factors

Emotional symptoms

Some studies reported the beneficial effect of emotional stability on QoL69 and the harmful effect of emotional problems.52 70 The emotional symptom studied most was depression28 29 32 34 35 39 40 51 55 65 69 71–75 followed by anxiety.39 40 51 69 71–74 76 Both symptoms were confirmed as risk factors for QoL in MS. Similarly, high levels of perceived stress,37 40 41 anger expression-in74 and apathy29 were identified as factors related to emotional regulation negatively affecting QoL in MS.

Personality domains

The role of personality domains was explored in several studies. Cyclothymic and depressive temperament were associated with a lower QoL in MS, in contrast to hyperthymic temperament, which was associated with higher QoL.77 Another study recognised extraversion as a personality trait related to higher QoL levels.69 Cioncoloni et al34 recognised introverted personality as a risk factor for QoL in MS, and finally, type D personality was another relevant factor.78

Coping strategies

Results with regard to coping strategies were consistent. Active coping, problem resolution, planning problem solving, cognitive positive restructuring, emotional and instrumental social support, emotional expression, acceptance and growth were related to a higher QoL in MS.51 71 79–82 In addition, Grech et al80 found a similar connection with restrained coping, Strober51 with humour and Mikula et al82 with stopping unpleasant emotion coping strategies. On the contrary, problem avoidance,71 81 behavioural disengagement,51 80 distancing,81 self-distraction,79 denial,51 79 emotion-focused and venting coping strategies,80 social withdrawal,71 wishful thinking,71 self-criticism,71 81 suppression80 and self-controlling coping70 were associated with lower QoL.

Coping strategies were also identified as relevant mediator variables. Problem-focused, emotion-focused and stopping unpleasant emotion coping strategies were partial mediators between fatigue83 or type D personality84 and QoL as measured by the Mental Composite Score (MCS).

Other psychological factors

According to Van Damme et al,85 acceptance of the illness is a protective factor for QoL. The role of flexible adjustment and tenacious goal pursuit in achieving personally blocked goals was not as clear, although their findings showed a trend towards a positive relationship.

Resilience was confirmed as a protective factor of QoL in MS.27 86 Moreover, Koelmel et al87 highlighted its role as a mediator variable in the relationship between social support and MCS.

High levels of self-efficacy,51 88 self-esteem,88 illness identity88 and sense of coherence89 correlated with higher QoL, and self-esteem mediated in the relationship of social support with MCS.90 Ultimately, cognitive fusion, the extent to which people feel fused with or attached to their thoughts, mediated the relationship between stigma and QoL in MS.91

Social factors

Social support92 and participation93 were positively related with QoL. Several mediators in this relationship were mentioned above.

Demographic factors

Employment was found to be the leading sociodemographic factor influencing QoL. Several studies displayed an association between unemployment and lower QoL.30 34 54 67 94 Others showed a positive correlation between jobs adapted to disability,94 job match and job satisfaction,41 high employment status33 41 and QoL in MS. Low socioeconomic status35 and financial straits37 were also risk factors for lower QoL.

Brola et al30 31 noted that not having access to an adequate pharmacological treatment put QoL in danger. Congruent with this finding, Boogar et al35 found a positive treatment experience to be a protective factor.

Other sociodemographic variables related to poorer QoL in MS were male sex,37 old age,30 31 unmarried or living with significant others,37 whereas a higher education was a protective factor.33

Disease history

Some of the selected studies examined QoL in MS in its early years. According to Possa et al,95 QoL decreased in the first year of diagnosis, as assessed by the MCS and Physical Composite Score (PCS). Stern et al96 found the worst QoL in the youngest group of patients with MS.

Calandri et al97 found that during the first 3 years from diagnosis, problem solving and avoidance coping strategies had a positive effect on QoL. Nourbakhsh et al98 also studied factors influencing the development of QoL in the first 3 years. Their results showed that higher baseline levels of fatigue and depression predicted worse QoL as assessed by the PCS, whereas lower cognitive functioning and higher fatigue predicted a worse MCS.

Another study on QoL in MS by Buhse et al99 focused on old age. These authors identified neurological impairment, physical disability, depression and comorbidity with thyroid disease as risk factors for worse QoL as assessed by the PCS in a sample of elderly patients with MS. On the contrary, being widowed and employed were identified as protective PCS factors.

In a longitudinal study, Kinkel et al100 showed that a second clinical event consistent with clinically defined MS, higher EDSS at the time of diagnosis and an earlier MS onset predicted a decrease in PCS 10 years after diagnosis. Bueno et al101 also showed that progression from benign MS to non-benign MS predicted a decrease in PCS 25–30 years after diagnosis.

Some longitudinal predictors of QoL identified have been: longer MS duration predicted worse QoL 2 years later,102 and worse EDSS predicted worse QoL 2,102 6,103 and 10104 years later. Depression predicted worse QoL 6103 and 10104 years later, and stronger pain105 and cognitive impairment104 predicted worse QoL 10 years later.

Interventions

Details of the selected articles on psychological intervention are presented in table 4.

Mindfulness-based therapies

All mindfulness-based therapy intervention programmes showed improvement in QoL at some evaluation point and at least in some QoL domains. Body-affective mindfulness intervention increased the general QoL score up to 6 months after treatment.106

Of the three studies on mindfulness-based stress reduction programmes, two showed a significant increase in QoL after treatment.107–109 One study109 only produced a small, insignificant increase after treatment and at the 3-month follow-up.

A community-based mindfulness programme resulted in a significant increase in MCS.110

Finally, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy did not show any significant difference in general QoL between the control and the experimental group; however, it did show significant differences in QoL: in health distress, mental well-being, role limitation due to emotional problems and cognitive performance.111

Cognitive behavioural

A wide spectrum of cognitive behavioural interventions was analysed.

In a study by Case et al,112 the experimental group attended 10 1-hour weekly sessions of healing light guided imagery. They found a greater increase in QoL in this group than with 10 hours of positive journaling in the active control group.

Blair et al113 focused intervention on emotion regulation. The design consisted of 16 1.5-hour biweekly sessions for 8 weeks. The intervention resulted in a significant increase in QoL 6 months after treatment.

Interventions by Calandri et al114 and Graziano et al115 had a comparable design. Participants were divided into two subgroups by age. Intervention comprised four to five 2-hour sessions over the course of 2 months, and one follow-up session 6 months after treatment. Calandri et al114 also included one follow-up session 12 months after treatment. At follow-up, the intervention groups in both studies had experienced an increase in QoL.

Three studies116–118 focused intervention on depressive symptoms. Kiropoulos et al116 and Chruzander et al117 found improvement in QoL at post-treatment and follow-up assessments. Kikuchi et al118 also found a post-treatment improvement, but not significant.

Two of the studies based intervention on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Pakenham et al119 implemented an 8-week programme aimed at training in resilience. QoL increased at treatment end and at 3-month follow-up. Proctor et al120 implemented an 8-week intervention comprising telephone calls and self-help ACT books. No significant increase in QoL was observed.

Social and group support

The following social support and group interventions had an impact on QoL in MS.

Abolghasemi et al121 implemented a 12-session supportive–expressive therapy programme, which improved QoL.

Jongen et al122 tested an intensive social-cognitive wellness programme involving the partner or other significant informal caregiver. The results showed an increase in the MCS at 1, 3 and 6 months from treatment and in the PCS 6 months after treatment. The results of the programme were evaluated again 12 months after treatment. The relapsing–remitting MS group showed an increase in PCS and MCS.123

Eliášová et al124 found more improvement across several QoL domains in patients with MS after self-help group sessions than in patients who did not attend the self-help groups. Liu125 detected an increase in physical and psychological QoL in women with MS after participating in a hope-based group therapy programme for 1 hour twice a week for 8 weeks.

Symptom and self-management-based therapies

Two studies analysed a fatigue self-management group therapy. Mulligan et al126 reported positive, but not significant, changes in QoL after their treatment. Thomas et al127 reported significant positive changes in physical health assessed by the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) and vitality as measured by the SF-36 in the intervention group 12 months after the treatment.

In addition to fatigue self-management, Ehde et al128 focused in their intervention on pain and depression self-management. The results were compared with an educational programme. There was a higher QoL post-treatment and 12-month follow-up score in the self-management group. Feicke et al129 implemented a programme focused on MS self-management. As in Ehde et al,128 improvements in QoL were still maintained at 6-month follow-up.

Other psychological intervention

LeClaire et al130 implemented a 5-week positive psychology programme. The results showed only a significant improvement in the SF-36 vitality subscale.

Discussion

First, the present systematic review was intended to identify risk and QoL protective factors in MS. The results showed that the EDSS was most employed for assessment of functional impairment.25–35 As expected, the number and severity of symptoms and associated impairment appeared to play a crucial role in QoL. Fatigue,28 29 39 40 42–52 cognitive impairment,39 50 52 53 63 66 67 and pain,35 39 50 51 55 56 in particular, were the focus of a large number of studies and were confirmed as important risk factors. Longitudinal studies suggested that greater fatigue,98 pain105 and cognitive impairment98 104 also predicted worse QoL up to 10 years later. This has important clinical implications, as treatment of the abovementioned symptoms should be prioritised. In general, functional impairment,102–104 as well as longer duration of illness,102 was predictor of QoL 2 to 10 years later, whereas disease progression101 from benign to non-benign MS predicted QoL as measured by the PCS up to 30 years later.

Among the emotional symptoms, there was convincing evidence that depression,28 29 32 34 35 39 40 51 55 66 69 71–75 along with depressive temperament77 and anxiety,38 40 51 69 71–74 76 were associated with lower QoL and that depression also predicted QoL up to 10 years later.104

The coping strategies applied obviously influenced QoL in MS, however their effect depended on the specific circumstances of the disease history. For example, problem solving and avoidance coping, normally classified as opposite strategies, both seemed to have a positive effect on the MCS in the first 3 years of diagnosis.97 However, in general, strategies associated with denial51 79 and avoidance of the challenges of the disease, such as problem avoidance,71 81 behavioural disengagement,51 80 distancing,81 self-distraction,79 social withdrawal71 and wishful thinking,71 were associated with a lower QoL. On the contrary, strategies based on acceptance and active commitment, such as active coping, humour, problem resolution, cognitive positive restructuring and emotional expression, led to higher QoL in MS.51 71 79–82 Obviously, there is a close connection between the active confrontation of the challenges of illness and specific personality-based convictions, such as a high self-efficacy. Thus, higher self-efficacy,51 88 self-esteem88 and sense of coherence89 improved QoL in MS.

Regarding sociodemographic influences on QoL, not surprisingly, unemployment, a low socioeconomic status35 and financial difficulties37 proved to be major risk factors.30 34 54 67 94 In keeping with the negative influence of the scarcity of resources, lack of access to therapy was also identified as a risk factor.30 31

The second aim of this systematic review was to study QoL in patients with MS at different times during their disease history. Two studies showed diminishing QoL in patients with MS in its early stage.95 96 This might have to do with the fact that patients being diagnosed with a severe chronic disease need a certain time to come to terms with this emotional shock. Oscillation between avoidance and problem solving, which both have a positive influence in the first 3 years after diagnosis,97 may be behind this inner struggle. In older patients, neurological impairment and physical disability,97 which represent the age-associated increase in physical impairment, were identified as risk factors for QoL in MS.

Finally, the third aim of this review was to analyse psychological interventions for the improvement of QoL in MS. Symptomatic improvement of psychopathology usually at the centre of psychotherapy outcome studies was not the primary focus of our review.131 Eight of the intervention studies specifically treated depressive symptomatology,106 110–112 115 117 118 either with mindfulness-based or cognitive behavioural approaches, both of which proved to be successful.

Three studies were specifically directed towards the treatment of fatigue112 126 127 by light guided imagery or self-management programmes. Both the imagery and self-management group intervention approaches were successful, whereas the individual self-management programme did not show significant improvement.

A variety of mindfulness-based approaches107–109 and a community-based intervention were directed at stress reduction.110 Three of the four studies showed some kind of improvement in QoL, including the only study with a control group.

Several of the interventions were designed to reinforce protective factors in patients with MS. Graziano et al115 focused on identity redefinition, sense of coherence and self-efficacy. Pakenham et al119 implemented a programme based on resilience training, and the programme by Blair et al113 focused on the improvement of emotional regulation. All of them were successful in improving QoL, confirming the alternative focus on protective factors instead of risk factors.

A wide spectrum of interventions based on social support concentrated on reinforcement of the social network of patients with MS, for example, self-help groups,124 hope-based group therapy,125 supportive–expressive therapy121 and social cognitive training with support partners.122 123 All interventions aimed at helping people overcome MS barriers in daily living by strengthening their social support, improving some aspects of QoL. This is consistent with the studies mentioned above92 93 and emphasises the importance of social support and participation as a protective factor for QoL.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study was the impossibility of carrying out a quantitative synthesis of the results, due to the heterogeneity of methodologies and designs in the articles included. Due to the vast number of topics and limited resources, our search was restricted to a 5-year period through January 2019.

Conclusions

This review was intended to give a broad overview of QoL in MS. The findings show the importance of clinical, psychosocial and demographic variables as QoL risk and protective factors. A variety of psychological interventions ranging from mindfulness-based and cognitive behavioural approaches to self-help groups addressing these factors were identified as promising options for improving QoL. These findings have important clinical implications. A sound biopsychosocial assessment of patients with MS in daily clinical practice is necessary to ensure the possibility of early identification of QoL risk factors and evidence-based psychological intervention is recommended to improve or stabilise QoL.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

IG-G, AM-R, RC and MÁP-S-G contributed equally.

Contributors: IG-G, AM-R, RC and MÁP-S-G contributed to conceptualisation, investigation, methodology, validation, writing original draft and writing review and editing.

Funding: This study was financially supported by the program of Formation of University Professor of Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport of Spain grant number: FPU 17/04240.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. Governance Basic documents. World health organisation, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution [Accessed 15 Dec 2019].

- 2.Patti F, Pappalardo A. Quality of life in patients affected by multiple sclerosis: a systematic review : Preedy VR, Watson RR, Handbook of disease burdens and quality of life measures. New York (NY: New York: Springer, 2010: 3769–83. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein U. The world Health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL) position paper from the world Helath organization. SocSciMed 1995;41:1403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Post MWM, Marcel WM. Definitions of quality of life: what has happened and how to move on. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2014;20:167–80. 10.1310/sci2003-167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gellert GA. The importance of quality of life research for health care reform in the USA and the future of public health. Qual Life Res 1993;2:357–61. 10.1007/BF00449431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benito-León J, Morales JM, Rivera-Navarro J, et al. A review about the impact of multiple sclerosis on health-related quality of life. Disabil Rehabil 2003;25:1291–303. 10.1080/09638280310001608591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyarat SY, Subih M, Rayan A, et al. Health related quality of life among patients with multiple sclerosis: the role of psychosocial adjustment to illness. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2019;33:11–16. 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yalachkov Y, Soydaş D, Bergmann J, et al. Determinants of quality of life in relapsing-remitting and progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019;30:33–7. 10.1016/j.msard.2019.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amtmann D, Bamer AM, Kim J, et al. People with multiple sclerosis report significantly worse symptoms and health related quality of life than the US general population as measured by PROMIS and NeuroQoL outcome measures. Disabil Health J 2018;11:99–107. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittock SJ, Mayr WT, McClelland RL, et al. Quality of life is favorable for most patients with multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Neurol 2004;61:679–86. 10.1001/archneur.61.5.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCabe MP, McKern S. Quality of life and multiple sclerosis: comparison between people with multiple sclerosis and people from the general population. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2002;9:287–95. 10.1023/A:1020734901150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt S, Vilagut G, Garin O, et al. [Reference guidelines for the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey version 2 based on the Catalan general population]. Med Clin 2012;139:613–25. 10.1016/j.medcli.2011.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrović N, Prlić N, Gašparić I, et al. Quality of life among persons suffering from multiple sclerosis. Medica Jadertina 2019;49:217–26 https://hrcak.srce.hr/234930 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Algahtani HA, Shirah BH, Alzahrani FA, et al. Quality of life among multiple sclerosis patients in Saudi Arabia. Neurosci 2017;22:261–6. 10.17712/nsj.2017.4.20170273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilski M, Gabryelski J, Brola W, et al. Health-Related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: links to acceptance, coping strategies and disease severity. Disabil Health J 2019;12:608–14. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pérez de Heredia-Torres M, Huertas-Hoyas E, Sánchez-Camarero C, et al. Occupational performance in multiple sclerosis and its relationship with quality of life and fatigue. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020;56:148–54. 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.05914-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochoa-Morales A, Hernández-Mojica T, Paz-Rodríguez F, et al. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis and its association with depressive symptoms and physical disability. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019;36:101386 10.1016/j.msard.2019.101386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorstyn DS, Roberts RM, Murphy G, et al. Employment and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analytic review of psychological correlates. J Health Psychol 2019;24:38–51. 10.1177/1359105317691587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt S, Jöstingmeyer P, Depression JP. Depression, fatigue and disability are independently associated with quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: results of a cross-sectional study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019;35:262–9. 10.1016/j.msard.2019.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ysrraelit MC, Fiol MP, Gaitán MI, et al. Quality of life assessment in multiple sclerosis: different perception between patients and neurologists. Front Neurol 2018;8:1–6. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Revicki DA, Osoba D, Fairclough D, et al. Recommendations on health-related quality of life research to support labeling and promotional claims in the United States. Qual Life Res 2000;9:887–900. 10.1023/A:1008996223999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baumstarck K, Boyer L, Boucekine M, et al. Measuring the quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis in clinical practice: a necessary challenge. Mult Scler Int 2013;2013:1–8. 10.1155/2013/524894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chacón-Moscoso S, Sanduvete-Chaves S, Sánchez-Martín M. The development of a checklist to enhance methodological quality in intervention programs. Front Psychol 2016;7:1811. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta S, Goren A, Phillips AL, et al. Self-Reported severity among patients with multiple sclerosis in the U.S. and its association with health outcomes.. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2014;3:78–88. 10.1016/j.msard.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rezapour A, Almasian Kia A, Goodarzi S, et al. The impact of disease characteristics on multiple sclerosis patients’ quality of life. Epidemiol Health 2017;39:e2017008–7. 10.4178/epih.e2017008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakazawa K, Noda T, Ichikura K, et al. Resilience and depression/anxiety symptoms in multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018;25:309–15. 10.1016/j.msard.2018.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciampi E, Uribe-San-Martin R, Vásquez M, et al. Relationship between social cognition and traditional cognitive impairment in progressive multiple sclerosis and possible implicated neuroanatomical regions. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018;20:122–8. 10.1016/j.msard.2018.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klevan G, Jacobsen CO, Aarseth JH, et al. Health related quality of life in patients recently diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2014;129:21–6. 10.1111/ane.12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brola W, Sobolewski P, Jantarski K. Multiple sclerosis: patient-reported quality of life in the Świętokrzyskie region. Med Stud Med 2017;33:191–8. 10.5114/ms.2017.70345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brola W, Sobolewski P, Fudala M, et al. Self-Reported quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: preliminary results based on the Polish MS registry. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:1647–56. 10.2147/PPA.S109520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernández-Jiménez E, Arnett PA. Impact of neurological impairment, depression, cognitive function and coping on quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis: a relative importance analysis. Mult Scler 2015;21:1468–72. 10.1177/1352458514562439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nickel S, von dem Knesebeck O, Kofahl C. Self-assessments and determinants of HRQoL in a German MS population. Acta Neurol Scand 2018;137:174–80. 10.1111/ane.12854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cioncoloni D, Innocenti I, Bartalini S, et al. Individual factors enhance poor health-related quality of life outcome in multiple sclerosis patients. significance of predictive determinants. J Neurol Sci 2014;345:213–9. 10.1016/j.jns.2014.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boogar IR, Talepasand S, Jabari M. Psychosocial and medical determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Noro Psikiyatr Ars 2018;55:29–35. 10.29399/npa.16983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gross HJ, Watson C, Characteristics WC. Burden of illness, and physical functioning of patients with relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional us survey. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2017;13:1349–57. 10.2147/NDT.S132079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cichy KE, Li J, Rumrill PD, et al. Non-vocational health-related correlates of quality of life for older adults living with multiple sclerosis. J Rehabil 2016;82:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Taylor BV, Simpson S, et al. Patient‐reported outcomes are worse for progressive‐onset multiple sclerosis than relapse‐onset multiple sclerosis, particularly early in the disease process. Eur J Neurol 2019;26:155–61. 10.1111/ene.13786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shahrbanian S, Duquette P, Kuspinar A, et al. Contribution of symptom clusters to multiple sclerosis consequences. Qual Life Res 2015;24:617–29. 10.1007/s11136-014-0804-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyncicova E, Kalina A, Vyhnalek M, et al. Health-Related quality of life, neuropsychiatric symptoms and structural brain changes in clinically isolated syndrome. PLoS One 2018;13:e0200254–13. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bishop M, Rumrill PD, Roessler RT. Quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis: replication of a three-factor prediction model. Work 2015;52:757–65. 10.3233/WOR-152203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leonavicius R. Among multiple sclerosis and fatigue. Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research 2016;22:141–5. 10.1016/j.npbr.2016.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garg H, Bush S, Gappmaier E. Associations between fatigue and disability, functional mobility, depression, and quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2016;18:71–7. 10.7224/1537-2073.2015-013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernández-Muñoz JJ, Morón-Verdasco A, Cigarán-Méndez M, et al. Disability, quality of life, personality, cognitive and psychological variables associated with fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2015;132:118–24. 10.1111/ane.12370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA, Marck CH, et al. Clinically significant fatigue: prevalence and associated factors in an international sample of adults with multiple sclerosis recruited via the Internet. PLoS One 2015;10:e0115541–18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aygunoglu SK, Çelebİ A, Vardar N, et al. Correlation of fatigue with depression, disability level and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neuropsychiatr 2015;52:247–51. 10.5152/npa.2015.8714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vister E, Tijsma ME, Hoang PD, et al. Fatigue, physical activity, quality of life, and fall risk in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2017;19:91–8. 10.7224/1537-2073.2015-077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tabrizi FM, Radfar M, Fatigue RM. Fatigue, sleep quality, and disability in relation to quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2015;17:268–74. 10.7224/1537-2073.2014-046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barin L, Salmen A, Disanto G, et al. The disease burden of multiple sclerosis from the individual and population perspective: which symptoms matter most? Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018;25:112–21. 10.1016/j.msard.2018.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kratz AL, Ehde DM, Hanley MA, et al. Cross-Sectional examination of the associations between symptoms, community integration, and mental health in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97:386–94. 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.10.093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strober LB. Quality of life and psychological well-being in the early stages of multiple sclerosis (MS): importance of adopting a biopsychosocial model. Disabil Health J 2018;11:555–61. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dymecka J, Bidzan M. Biomedical variables and adaptation to disease and health-related quality of life in Polish patients with MS. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2678. 10.3390/ijerph15122678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colbeck M, processing S. Sensory processing, cognitive fatigue, and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Can J Occup Ther 2018;85:169–75. 10.1177/0008417417727298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abdullah EJ, Badr HE. Assessing the quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis in Kuwait: a cross sectional study. Psychol Health Med 2018;23:391–9. 10.1080/13548506.2017.1366660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams AE, Vietri JT, Isherwood G, et al. Symptoms and association with health outcomes in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a US patient survey. Mult Scler Int 2014;2014:1–8. 10.1155/2014/203183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marck CH, De Livera AM, Weiland TJ, et al. Pain in people with multiple sclerosis: associations with modifiable lifestyle factors, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and mental health quality of life. Front Neurol 2017;8:1–7. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Milinis K, Tennant A, Young CA. Spasticity in multiple sclerosis: associations with impairments and overall quality of life. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;5:34–9. 10.1016/j.msard.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zettl UK, Henze T, Essner U, et al. Burden of disease in multiple sclerosis patients with spasticity in Germany: mobility improvement study (move I). Eur J Health Econ 2014;15:953–66. 10.1007/s10198-013-0537-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khalaf KM, Coyne KS, Globe DR, et al. The impact of lower urinary tract symptoms on health‐related quality of life among patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurourol Urodyn 2016;35:48–54. 10.1002/nau.22670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vitkova M, Rosenberger J, Krokavcova M, et al. Health-Related quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients with bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:987–92. 10.3109/09638288.2013.825332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qaderi K, Merghati Khoei E. Sexual problems and quality of life in women with multiple sclerosis. Sex Disabil 2014;32:35–43. 10.1007/s11195-013-9318-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schairer LC, Foley FW, Zemon V, et al. The impact of sexual dysfunction on health-related quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014;20:610–6. 10.1177/1352458513503598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma S, Rui X, Qi P, et al. Sleep disorders in patients with multiple sclerosis in China. Sleep Breath 2017;21:149–54. 10.1007/s11325-016-1416-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.White EK, Sullivan AB, Drerup M. Short report: impact of sleep disorders on depression and Patient-Perceived health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2019;21:10–14. 10.7224/1537-2073.2017-068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grech LB, Kiropoulos LA, Kirby KM, et al. The effect of executive function on stress, depression, anxiety, and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2015;37:549–62. 10.1080/13803395.2015.1037723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Samartzis L, Gavala E, Zoukos Y, et al. Perceived cognitive decline in multiple sclerosis impacts quality of life independently of depression. Rehabil Res Pract 2014;2014:1–6. 10.1155/2014/128751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Campbell J, Rashid W, Cercignani M, et al. Cognitive impairment among patients with multiple sclerosis: associations with employment and quality of life. Postgrad Med J 2017;93:143–7. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sgaramella TM, Carrieri L, Stenta G, et al. Self-Reported executive functioning and satisfaction for quality of life dimensions in adults with multiple sclerosis. Int J Child Heal Hum Dev 2014;7:167 10.1186/1471-244X-13-253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paziuc LC, Radu MR. The influence of mixed anxiety-depressive disorder on the perceived quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov, Seriels VI: Medical Sciences 2018;11:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phillips LH, Henry JD, Nouzova E, et al. Difficulties with emotion regulation in multiple sclerosis: links to executive function, mood, and quality of life. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2014;36:831–42. 10.1080/13803395.2014.946891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hernández-Ledesma AL, Rodríguez-Méndez AJ, Gallardo-Vidal LS, et al. Coping strategies and quality of life in Mexican multiple sclerosis patients: physical, psychological and social factors relationship. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018;25:122–7. 10.1016/j.msard.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prisnie JC, Sajobi TT, Wang M, et al. Effects of depression and anxiety on quality of life in five common neurological disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018;52:58–63. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alsaadi T, Hammasi KE, Shahrour TM, et al. Depression and anxiety as determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis - United Arab Emirates. Neurol Int 2017;9:75–8. 10.4081/ni.2017.7343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Labiano-Fontcuberta A, Mitchell AJ, Moreno-García S, et al. Impact of anger on the health-related quality of life of multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 2015;21:630–41. 10.1177/1352458514549399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fernández-Muñoz JJ, Cigarán-Méndez M, Navarro-Pardo E, et al. Is the association between health-related quality of life and fatigue mediated by depression in patients with multiple sclerosis? A Spanish cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e016297–6. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pham T, Jetté N, Bulloch AGM, et al. The prevalence of anxiety and associated factors in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018;19:35–9. 10.1016/j.msard.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Salhofer-Polanyi S, Friedrich F, Löffler S, et al. Health-Related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: temperament outweighs EDSS. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:1–6. 10.1186/s12888-018-1719-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Demirci S, Demirci K, Demirci S. The effect of type D personality on quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neuropsychiatr 2017;54:272–6. 10.5152/npa.2016.12764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zengin O, Erbay E, Yıldırım B, et al. Quality of life, coping, and social support in patients with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Tnd 2017;23:211–8 https://doi.org/ 10.4274/tnd.37074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grech LB, Kiropoulos LA, Kirby KM, et al. Target coping strategies for interventions aimed at maximizing psychosocial adjustment in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2018;20:109–19. 10.7224/1537-2073.2016-008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Farran N, Ammar D, Darwish H. Quality of life and coping strategies in Lebanese multiple sclerosis patients: a pilot study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;6:21–7. 10.1016/j.msard.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mikula P, Nagyova I, Krokavcova M, et al. Coping and its importance for quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:732–6. 10.3109/09638288.2013.808274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mikula P, Nagyova I, Krokavcova M, et al. The mediating effect of coping on the association between fatigue and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med 2015;20:653–61. 10.1080/13548506.2015.1032310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mikula P, Nagyova I, Krokavcova M, et al. Do coping strategies mediate the association between type D personality and quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis? J Health Psychol 2018;23:1557–65. 10.1177/1359105316660180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Van Damme S, De Waegeneer A, Debruyne J. Do flexible goal adjustment and acceptance help preserve quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis? Int J Behav Med 2016;23:333–9. 10.1007/s12529-015-9519-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nery-Hurwit M, Yun J, Ebbeck V. Examining the roles of self-compassion and resilience on health-related quality of life for individuals with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Health J 2018;11:256–61. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koelmel E, Hughes AJ, Alschuler KN, et al. Resilience mediates the longitudinal relationships between social support and mental health outcomes in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:1139–48. 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.09.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wilski M, Tasiemski T. Health-Related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: role of cognitive appraisals of self, illness and treatment. Qual Life Res 2016;25:1761–70. 10.1007/s11136-015-1204-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Calandri E, Graziano F, Borghi M, et al. Depression, positive and negative affect, optimism and health-related quality of life in recently diagnosed multiple sclerosis patients: the role of identity, sense of coherence, and self-efficacy. J Happiness Stud 2018;19:277–95. 10.1007/s10902-016-9818-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]