Abstract

Non-sebaceous lymphadenoma (NSLA) is a rare benign salivary gland tumour with lymphoid and epithelial components and without sebaceous differentiation. The large majority of the reported cases arise within the parotid gland. We present an NSLA arising from the submandibular gland. The tumour presented as a painless longstanding neck lump. Ultrasound, fine needle aspiration, MRI and positron emission tomography found features supportive of squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was treated with surgery for oropharyngeal carcinoma of unknown origin, in accordance with local and national guidelines. The final histological assessment revealed the level Ib neck lesion to be NSLA. Although a rare occurrence, these lesions may pose a diagnostic challenge in the head and neck cancer pathway.

Keywords: pathology, otolaryngology / ENT

Background

Non-sebaceous lymphadenoma (NSLA) is a benign salivary tumour characterised by intimately intermingled lymphoid and epithelial components devoid of sebaceous, oncocytic, clear cell and mucinous differentiation.1 2 NSLA was first described in a single case in 1991,3 and recognised as a separate entity to the more common sebaceous lymphadenoma by the WHO in 2005.4 There has been a series of case reports and two case series which amount to 44 reported cases. Of these, only two cases arise from the submandibular gland with the remainder arising from the parotid except one periauricular, one from the lacrimal gland and two from cervical lymph nodes.5–9 Due to the rarity of the tumour, pathogenesis and aetiology is poorly understood and misdiagnosis is common with malignancy being an important differential diagnosis to consider.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old woman presented via an urgent general practice referral to the ear, nose and throat, and head and neck cancer clinic with a painless neck lump first noticed 8 months ago. The patient had a history of Graves’ disease treated with radioiodine and subsequent long-term thyroxine, and a recently resected benign cylindroma of the left frontal scalp. The patient had no history of smoking and minimal alcohol consumption.

On examination, the lump was hard and well circumscribed, measuring 3 cm in the left level Ib neck region, with the clinical appearance of a lymph node in the submandibular triangle. The remainder of the aerodigestive tract visualised by pharyngolaryngoscopy appeared normal.

Investigations

Investigation with ultrasound scan (USS) and fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was carried out. USS showed a 15 mm diameter lymph node with almost complete effacement of the hilum but preserved hilar vascularity and some visible peripheral vascularity. The adjacent level Ib lymph nodes were mildly enlarged but reactive in appearance. No abnormalities of the parotid, submandibular or thyroid glands were identified.

Fine needle aspiration found cells containing large nuclei with nucleoli, moderate cytoplasm and focal keratin pearls. Evidence of keratinisation was demonstrated on Papanicolaou staining of the epithelial cells suggestive of malignancy concluding a likely diagnosis of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. On MRI, the node appeared pathological with subtle heterogeneity and gadolinium enhancement. The palatine tonsils were asymmetrical with minimal right sided enlargement.

Following review at the head and neck cancer multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting, urgent positron emission tomography CT (PET-CT) conferred the node as avid with fluorodeoxyglucose enhancement (figure 1). No obvious upper aerodigestive tract or distant primary site was identified. Focal metabolic activity was found bilaterally in the external iliac lymph nodes, which were subsequently found to be benign on FNAB.

Figure 1.

Positron emission tomography CT showing fluorodeoxyglucose enhancement of the left submandibular gland.

Differential diagnosis

The features of the clinical presentation, USS appearance and cytology findings, with focal enhancement on PET-CT, supported a diagnosis of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary.

Treatment

Following further MDT discussion, in line with local and national guidelines for management of head and neck carcinoma of unknown primary, a panendoscopy with transoral robotic base of tongue mucosectomy, bilateral tonsillectomy and selective left neck dissection of levels Ib–IV was advised and performed on an urgent basis.

Outcome and follow-up

The diagnostic tongue base mucosectomy and tonsillectomies showed no evidence of malignancy. From the ipsilateral selective neck dissection, morphological features on microscopy together with the immunohistochemical studies confirmed an NSLA arising from the left submandibular gland. Forty-nine lymph nodes were clear of disease.

Microscopy found a well-circumscribed submandibular lesion featuring thin encapsulation. Scattered throughout and demonstrating with a relatively even distribution were anastomosing trabeculae and irregular nests of squamous epithelium. These featured slightly hyperchromatic basal cells which showed maturation centrally with frequently observed keratin pearls. Intraepithelial lymphocytosis was present. The epithelial cells though demonstrated prominent nucleoli. Occasional epithelial islands showed marked cystic dilatation giving an impression of pseudoglandular appearance with luminal fibrinous and proteinaceous secretions. No sebaceous elements were present. Mitoses were inconspicuous and necrosis not a feature. The lesional stroma was composed of benign lymphoid tissue with scattered variably sized reactive lymphoid follicles featuring germinal centres. There was no vascular invasion. The lesional interface with the submandibular gland further confirmed its salivary gland origin where some of the salivary lobules showed retained architecture but with lesional tissue closely associated with the normal submandibular acinar structures. In the sampled capsular periphery, epithelial islands appeared irregular and pseudoinfiltrative. Lack of a subcapsular sinus or cortical/medullary sinuses further disconfirmed the sample as a lymph node (figures 2–5).

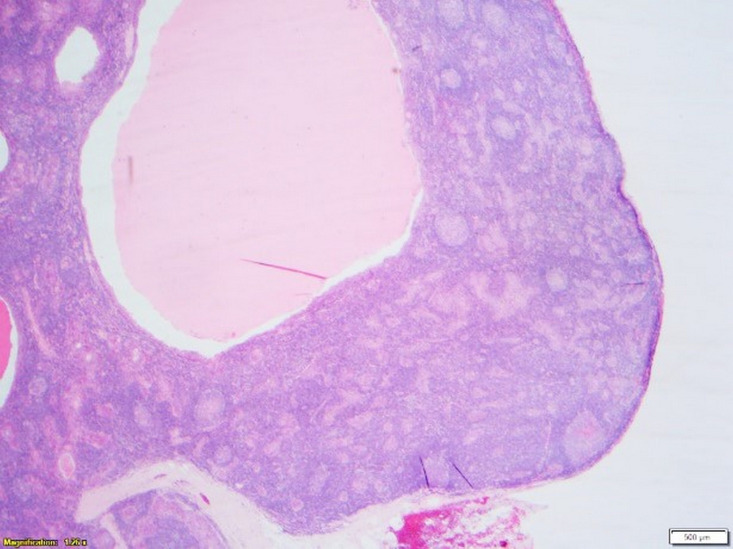

Figure 2.

Low-power view (×2) showing the well-circumscribed and well-demarcated lesion suggestive of cyst formation.

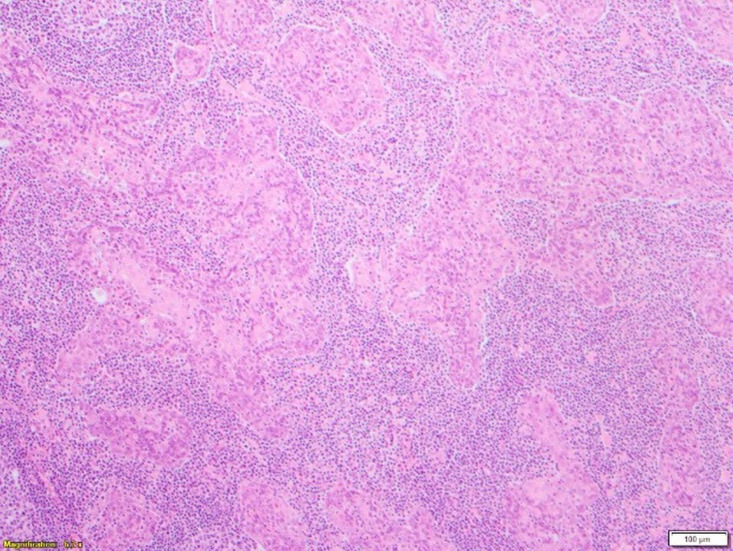

Figure 3.

Lesion showing trabeculae of squamous epithelium.

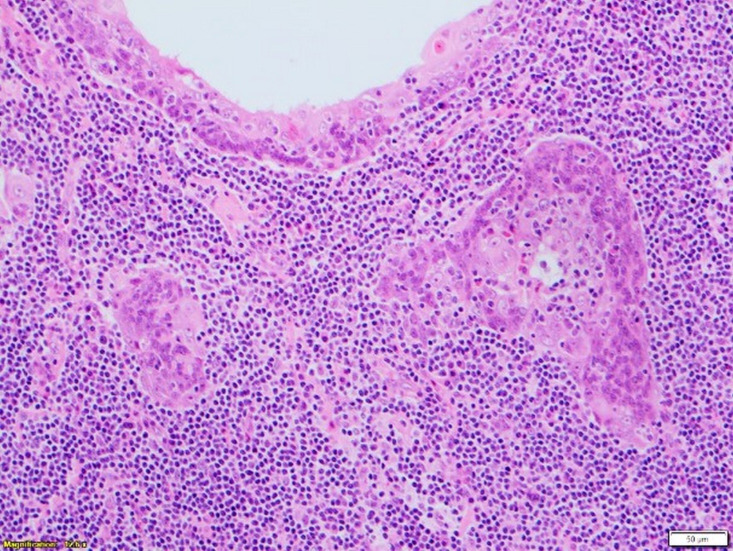

Figure 4.

High-power view (×10) showing part of a cystic island and benign lymphoid parenchyma.

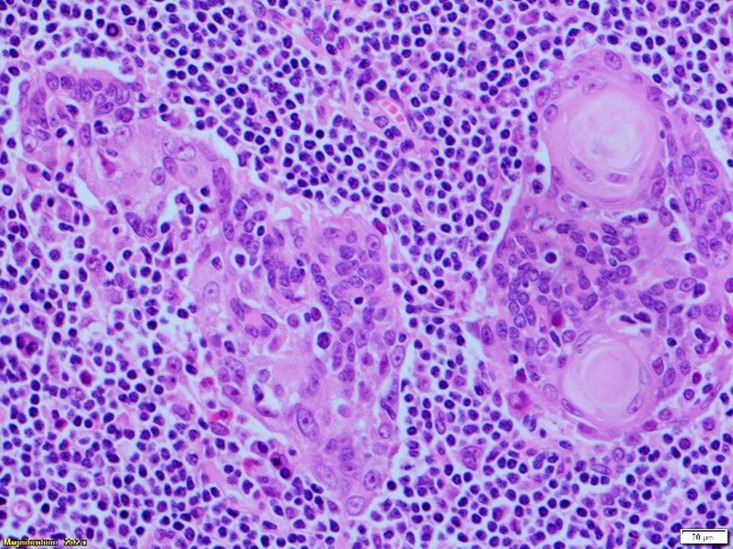

Figure 5.

High-power view (×20) showing lymphoepithelium forming small keratin pearls.

Immunoprofile studies further confirmed epithelial differentiation. Epithelial components were positive for AE1/3, epithelial membrane antigen, cytokeratin 7 (CK7) and CK5. Within the basal levels, p63 was pronounced. Staining for S100 showed scattered dendritic cells. No true mucinous secretions were identified on diastase periodic acid-Schiff or Alcian blue periodic acid-Schiff. Proliferation Index ki-67 was low with <5% of cells in cycle. In viral studies, p16 showed weak cytoplasmic uptake significantly different to the expression pattern of human papilloma virus driven squamous cell carcinoma. Androgen receptor and in situ hybridisation for Epstein-Barr virus-encoded ribonucleic acid was negative.

The patient recovered well from surgery without complications. The benign diagnosis, although subject to overtreatment, was received well by the patient and rendered no indication for further treatment.

Discussion

Lymphadenomas (LADs) are rare and poorly understood benign salivary gland tumours in which a benign squamous epithelial cell proliferation with an associated benign lymphoid parenchyma are observed. Lymphadenomas are broadly categorised into two categories: sebaceous and non-sebaceous. NSLAs, which are less common, lack sebaceous differentiation in the epithelial component.5 6 Contrasting theories in the literature explain the lymphoid component of NSLAs. Reactive tumour associated lymphoid tissue is described by some authors, whereas others speculate the glandular inclusions within lymph nodes give rise to the tumours, similar to Warthin’s tumours.1 2 5 10 11

Features of NSLA appear to be heterogeneous with respect to histology, age and gender distribution. Median age from two case series ranges from 50 to 65 years.1 5 Tumours present as long-standing painless masses usually in the parotid gland. Malignant transformation of NSLA is described in one reported case.9 There may be an association between LADs and immunomodulatory therapy. A study of 33 LADs found 30% of patients had a history of immunomodulatory drug therapy for autoimmune diseases, cancer or pre-existing low-grade malignancy.5 We note that in this case, the patient had a history of autoimmune disease and recently resected benign cylindroma but without a history of immunomodulatory therapy. In two case series of NSLA, of the total 22 cases, squamous differentiation with keratinisation was seen in 2 cases.5 We note that in this case, keratinisation was demonstrated on cytology and histology as previously described.

There is a paucity of literature describing NSLAs arising from the submandibula gland. Two cases, both in females, are described as part of a case series.5 It appears that lymphadenomas more commonly arise from the parotid gland.1 5–7 9 This case is a rare but useful example of the diagnostic challenges faced with neck lumps. A core biopsy may have provided a better understanding of the histology and should be used as an adjunct for those lesions considered clinically ‘unusual’ in their presentations.

In the UK, there are national multidisciplinary guidelines which recommend all patients presenting with confirmed cervical lymph node metastatic squamous cell carcinoma undergo whole-body PET-CT scan, panendoscopy with directed biopsies, bilateral tonsillectomy and tongue base mucosectomy if available, with consideration of concomitant chemotherapy with radiation or neck dissection depending on tumour and patient factors.12 During every stage of investigation until definitive histology, this case mimicked the behaviour of a squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary. To our knowledge, there are no reports diagnosing NSLA prior to histopathology reporting of the entire tumour.7

Learning points.

Non-sebaceous lymphadenoma (NSLA) can pose a diagnostic challenge in the context of the head and neck cancer pathway and multidisciplinary team decision-making due to its rarity, unusual site and its ability to mimic malignancy both clinically and in all investigations prior to histological examination.

It is important to be mindful of rare entities such as NSLA in the management of patients with head and neck cancer.

A core biopsy may have provided a better understanding of the histology and should be used as an adjunct for those lesions considered clinically ‘unusual’ in their presentations.

Footnotes

Contributors: GG conducted literature review, editing and writing of report. DJ undertook initial research of case, sourcing and writing case materials and reviewing manuscript. GP provided histopathology images with annotations, pathology reporting and specialist head and neck pathology review and recommendations, and reviewed manuscript, and was a pathologist involved in patient's care. EO provided specialist head and neck review and recommendations, reviewed the case and research, and was the surgeon involved in patient's care.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Weiler C, Agaimy A, Zengel P, et al. Nonsebaceous lymphadenoma of salivary glands: proposed development from intraparotid lymph nodes and risk of misdiagnosis. Virchows Arch 2012;460:467–72. 10.1007/s00428-012-1225-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auclair PL. Tumor-Associated lymphoid proliferation in the parotid gland. A potential diagnostic pitfall. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994;77:19-26. 10.1016/s0030-4220(06)80102-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auclair PL, Ellis GL, Gnepp DR. Other benign epithelial neoplasms : Ellis GL, Auclair PL, Gnepp DR, “Surgical pathology of the salivary glands”. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, et al. World Health organization classification of tumours—pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Iarc 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seethala RR, Thompson LDR, Gnepp DR, et al. Lymphadenoma of the salivary gland: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 33 tumors. Mod Pathol 2012;25:26–35. 10.1038/modpathol.2011.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu G, He J, Zhang C, et al. Lymphadenoma of the salivary gland: report of 10 cases. Oncol Lett 2014;7:1097–101. 10.3892/ol.2014.1827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamanaka H, Hasegawa H, Tanaka M, et al. Parotid gland Non-Sebaceous Lymphadenoma: a case report. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019;57:42–5. 10.5152/tao.2019.4129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pau M, Brcic L, Seethala RR, et al. Non-sebaceous lymphadenoma of the lacrimal gland: first report of a new localization. Virchows Arch 2018;473:127–30. 10.1007/s00428-018-2322-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kara H, Sönmez S, Bağbudar S, et al. Malignant transformation of parotid gland Non-sebaceous Lymphadenoma: case report and review of literature. Head Neck Pathol 2020. 10.1007/s12105-020-01133-3. [Epub ahead of print: 29 Jan 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musthyala NB, Low SE, Seneviratne RH. Lymphadenoma of the salivary gland: a rare tumour. J Clin Pathol 2004;57:1007. 10.1136/jcp.2004.018028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii A, Kawano H, Tanaka S, et al. Non-sebaceous lymphadenoma of the salivary gland with serous acinic cell differentiation, a first case report in the literature. Pathol Int 2013;63:272–6. 10.1111/pin.12061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackenzie K, Watson M, Jankowska P, et al. Investigation and management of the unknown primary with metastatic neck disease: United Kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines. J Laryngol Otol 2016;130:S170–5. 10.1017/S0022215116000591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]