Abstract

The chemical recycling of poly(lactide) was investigated based on depolymerization and polymerization processes. Using methanol as depolymerization reagent and zinc salts as catalyst, poly(lactide) was depolymerized to methyl lactate applying microwave heating. An excellent performance was observed for zinc(II) acetate with turnover frequencies of up to 45000 h−1. In a second step the monomer methyl lactate was converted to (pre)poly(lactide) in the presence of catalytic amounts of zinc salts. Here zinc(II) triflate revealed excellent performance for the polymerization process (yield: 91 %, Mn ∼8970 g/mol). Moreover, the (pre)poly(lactide) was depolymerized to lactide, the industrial relevant molecule for accessing high molecular weight poly(lactide), using zinc(II) acetate as catalyst.

Keywords: green chemistry, catalysis, polymers, recycling, depolymerization

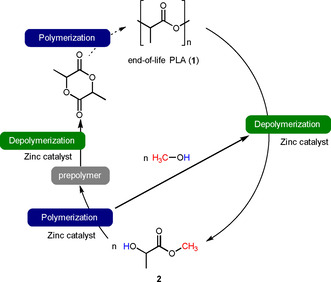

Plastic passion: The chemical recycling of end‐of‐life poly(lactide) is investigated. The recycling is based on depolymerization and polymerization using straightforward zinc salts as catalyst.

Plastics derived from renewable resources can be valuable for a future circular and resource‐efficient chemistry/economy. Moreover, this type of plastics have some advantages compared to fossil resource‐based plastics.[ 1 , 2 ] In recent times, poly(lactide) plastics (PLA, 1, Scheme 1) have been established as most important representative produced on a ∼0.2 m t/y scale. [3] PLA is accessible by a multi‐step process. Initially, in biological transformation carbon dioxide, water and solar energy are converted to biomass, which is subsequently converted to lactic acid. [4] Afterwards, lactic acid is subjected to polycondensation to generate polymer/oligomer 1. Another option is the oligomerization of lactic acid and subsequent degradation to lactide, which can be subjected to ring‐opening polymerization to form 1. PLA can be used in a wide range of applications (e. g., food packaging, pharmaceuticals). Nevertheless, after completing the purpose PLA is designated as End‐of‐Life PLA (EoL‐PLA) and it has to be treated as waste. As a value of PLA the bio‐degradability has been discussed. [5] However, the dwell time in composting plants is too short for complete degradation. As an alternative EoL‐PLA can be degraded by incineration to release the stored energy and produce CO2 and water, which can go through the processes again (vide supra). In contrast to fossil resource‐based plastics, a circular process and carbon‐neutrality is attainable on a short time scale.[ 6 , 7 ] Nevertheless, a drawback of this approach is the necessity for substitution of the EoL‐PLA by fresh PLA, which requires land use and cultivation time, therefore a competition with other agricultural goods can occur. To overcome these issues/limitations a recycling of PLA plastics can be a useful tool. In this regard, the chemical recycling based on depolymerizations and polymerizations can offer benefits. [8] In more detail, the depolymerization process transforms the polymer to the monomer, while the polymerization regenerates the polymer from the monomer (Scheme 1). Numerous chemical recycling methods for EoL‐PLA have been accounted.[ 9 , 10 , 11 ] Especially, the alcoholysis of EoL‐PLA has been studied. In more detail, the EoL‐PLA is reacted with methanol to generate methyl lactate (2) containing the monomeric unit of PLA. The methyl lactate can easily be converted to lactic acid the starting material for 1 (industrially established route). On the other hand, 2 can be polymerized to PLA (less investigated route).[ 12 , 13 ] In both processes methanol is formed, which can be resent to the depolymerization process. Notably, for performing the depolymerization as well as the polymerization catalysts are essential. In case of methanolytic depolymerization catalytic amounts of zinc complexes among others have been successfully applied. [11] However, the application of complexes requires the upstream synthesis of the complex and the corresponding ligand. Therefore, the use of simple zinc salts can be beneficial with respect to catalyst costs and resource‐efficiency. Indeed, Collinson and coworker reported the use of simple zinc(II) acetate as catalyst (1.4 mol%) resulting in a yield of 70 % of 2 after 15 hours at reflux. [11c] Moreover, for the synthesis of 1 starting from 2 metal catalysis has been reported. [13]

Scheme 1.

Chemical recycling concept for PLA.

However, based on the general reaction path we wonder if catalysts based on simple zinc salts can enable the depolymerization as well as the polymerization, which can add some value to a circular and resource‐efficient chemistry/economy.

Initially, as model for optimization of the depolymerization reaction conditions transparent end‐of‐life plastic cups containing poly(lactide) (1 a, Mn=57,500 g/mol, Mw=240,800 g/mol, D=4.2, PLLA) as major component was investigated (Table 1). Small pieces of the PLA 1 a (2.78 mmol with respect to the monomer unit, implying that 1 a contains 100 % of PLA), an excess of methanol (67.5 equivalents with respect to the monomer unit of 1 a) and catalytic amounts of Zn(OTf)2 (1.0 mol% with respect to the monomer unit of 1 a) were added to a microwave glass vial. After sealing the vial the mixture was stirred and reacted at 160 °C applying microwave heating (MW) for 10 min, meanwhile the PLA was completely dissolved (Table 1, entry 2). After cooling to ambient temperature an aliquot was added to CDCl3 for determination of the yield/conversion by 1H NMR analysis. The existence of the depolymerization product 2 was proven by the presence of a singlet at δ = 3.78 ppm, which corresponds to the methyl ester functionality (‐C(=O)OCH 3). Additionally, a doublet at δ = 1.41 ppm (3JHH=6.91 Hz, CH 3CH‐function) and a quartet of doublets at δ = 4.28 ppm (3JHH=6.91 Hz, 3JHH=5.20 Hz, CH3CHOH‐function) were observed, which matches to compound 2. For Zn(OTf)2 as catalyst an excellent yield of >99 % was detected (Table 1, entry 2). The yield of 2 was calculated by relating the integral of the CH3CHOH‐function of 2 to the integral of the CH3CHOR‐function of the polymer/oligomer leftover (∼5.17 ppm). Moreover, other zinc salts were tested revealing also excellent yield for Zn(OAc)2, while zinc halides showed an inferior performance (Table 1, entries 3–6). [14] Importantly, in the absence of any zinc salt no product formation was observed (Table 1, entry 1).

Table 1.

Depolymerization of 1 a using zinc catalysis – optimization of reaction conditions.

|

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entry |

Catalyst |

Catalyst loading [mol %] |

MeOH [equiv.] |

T [°C] |

t [min] |

Yield 2 [%][b] |

TOF [h−1][c] |

|

1 |

– |

– |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

<1 |

<1 |

|

2 |

Zn(OTf)2 |

1.0 |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

>99 |

600 |

|

3 |

ZnCl2 |

1.0 |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

60 |

360 |

|

4 |

ZnBr2 |

1.0 |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

28 |

168 |

|

5 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

1.0 |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

>99 (92)[d] |

600 |

|

6 |

Zinc(II) methacrylate |

1.0 |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

>99 |

600 |

|

7 |

Poly(zinc(II) methacrylate) |

1.0 |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

<1 |

<1 |

|

8[e] |

Poly(zinc(II) methacrylate) |

1.0 |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

<1 |

<1 |

|

9 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

1.0 |

67.5 |

140 |

10 |

>99 |

600 |

|

10 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

1.0 |

67.5 |

120 |

10 |

>99 |

600 |

|

11 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

1.0 |

67.5 |

100 |

10 |

91 |

546 |

|

12 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

0.5 |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

>99 |

1200 |

|

13 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

0.25 |

67.5 |

160 |

10 |

>99 |

2400 |

|

14 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

0.5 |

67.5 |

160 |

5 |

>99 |

2400 |

|

15 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

0.25 |

67.5 |

160 |

5 |

72 |

3456 |

|

16 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

0.1 |

67.5 |

180 |

1 |

75 |

45000 |

|

17 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

0.5 |

56.3 |

160 |

10 |

>99 |

600 |

|

18[f] |

Zn(OAc)2 |

1.0 |

67.5 |

64.7 |

1440 |

>99 |

4 |

[a] Conditions: 1 a (transparent PLA cup), 2.78 mmol with respect to the monomer unit, it is presumed that 1 a is composed of 100 % of PLA), catalyst (0‐1.0 mol%, 0–0.0278 mmol with respect to the monomer unit of 1 a), MeOH (56.3‐67.5 equiv. with respect to the monomer unit of 1 a), temperature: 100–180 °C (microwave heating), time: 1–10 min. [b] The yield of 2 bases on 1H NMR spectroscopy. [c] The TOF was calculated: (mole product/mole catalyst)*h−1. The TOF was calculated using the yield of 2 after the designated time. [d] Isolated yield. [e] Anisole (1 g) or 1,2,4‐trichlorbenzene (1 g) or THF (3 g) as cosolvent. [f] Reaction was performed under reflux using oil bath heating.

In case of Zn(OAc)2 chemical 2 was isolated in 92 % yield from the reaction mixture. In detail, the methanol and compound 2 were separated from the catalyst by distillation under vacuum to circumvent side/back processes (polymerization). Afterwards, the mixture of 2 (b.p. ∼144 °C) and methanol (b.p. ∼65 °C) was separated by distillation.Next the reaction temperature was decreased stepwise to 100 °C showing still a good yield of 91 % at 100 °C (Table 1, entries 9–11).

Interestingly, with a Zn(OAc)2 loading of 0.25 mol% an excellent performance was still noticed, which corresponds to a turnover frequency (TOF) of 2400 h−1 (Table 1, entry 13). By increasing the temperature to 180 °C a further increase of the TOF to 45000 h−1 was observed (Table 1, entry 16). Noteworthy, the Zn(OAc)2 catalyst outperform our earlier reported systems, e. g. DMAP (∼178 h−1), KF (∼816 h−1), bismuth subsalicylate (∼13800 h−1) or Sn(Oct)2 (∼39600 h−1).[ 10j , 10k , 10l , 10m ] Finally, the reaction was performed under conventional heating under refluxing conditions (Table 1, entry 18). Here 2 was obtained in >99 % yield after 24 hours.

Afterwards, the protocol was tested in the depolymerization of different PLA‐products (Table 2). In all cases excellent performance with yields >99 % was observed for the Zn(OAc)2 catalyst. Moreover, the depolymerization of PLA 1 a was studied in the presence of different kinds of polymers, which can be beneficial for plastic separation (Table 3). Therefore, best conditions for 1 a were applied (1.0 mol% Zn(OAc)2, 160 °C, 67.5 equiv. methanol, 5 min). In more detail, PLA 1 a was mixed with an equimolar amount of another polymer (based on its repeating unit) and the mixture was subjected to depolymerization. In all cases excellent catalyst performance was observed for the conversion of PLA to methyl lactate. Importantly, most additional polymers were recovered. Only in case of poly(bisphenol A carbonate) the depolymerization products bisphenol A and dimethyl carbonate were detected by 1H NMR.

Table 2.

Zn(OAc)2 catalyzed depolymerization of PLA goods.

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Entry[a] |

Product |

Yield of 2 [%][b] |

|

1 |

transparent cup (1 oz) (1 a) |

>99 |

|

2 |

transparent cup (250 mL) (1 b) |

>99 |

|

3 |

transparent disposable food box (1 c) |

>99 |

|

4 |

transparent sushi box cover (1 d) |

>99 |

|

5 |

transparent bottle (1 e) |

>99 |

|

6 |

drinking straw with green strips (1 f) |

>99 |

|

7 |

disposable fork with talcum powder (1 g) |

>99 |

|

8 |

lid for espresso mugs (contains ∼20‐30 % talcum powder) (1 h) |

>99 |

|

9 |

lid for coffee mugs (1 i) |

>99 |

|

10 |

black lid for coffee mugs (1 j) |

>99 |

|

11 |

sushi box (black base) (1 k) |

>99 |

|

12 |

blue ice cream spoon (1 l) |

>99 |

[a] Conditions: 1 a–1 l (200.0 mg, 2.78 mmol with respect to the monomer unit), Zn(OAc)2 (5.1 mg, 1.0 mol%, 0.0278 mmol with respect to the monomer unit of 1), MeOH (6.0 g, 187.3 mmol, 67.5 equiv. with respect to monomer unit of 1), temperature: 160 °C (microwave heating), time: 10 min. [b] The yield of 2 bases on 1H NMR spectroscopy. The amount of substance of 2 was linked to the amount of substance of PLA.

Table 3.

Zn(OAc)2 catalyzed depolymerization of PLA in the presence of additional polymers.

|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Entry[a] |

Additional polymer B |

Yield of 2 [%][b] |

Yield [%][c] |

|

1 |

– |

>99 |

<1 |

|

2 |

Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

3 |

Poly(ϵ‐caprolactone) (PCL) (Mn ∼80,000 g/mol) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

4 |

Poly((R)‐hydroxybutyric acid) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

5 |

Poly(bisphenol A carbonate) |

>99 |

87[d] |

|

6 |

Nylon 6 |

>99 |

<1 |

|

7 |

Poly(phenylene sulfide) (PPS) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

8 |

Poly(ethylene) (PE) (Mn ∼1,700 g/mol) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

9 |

Poly(styrene) (PS) (Mw ∼35,000 g/mol) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

10 |

Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) (Mw ∼48,000 g/mol) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

11 |

Poly(vinyl alcohol) (Mw ∼67,000 g/mol) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

12 |

Poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether (Mn ∼5,000 g/mol) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

13 |

Epoxy resin (Mn ∼1,750 g/mol) |

>99 |

<1 |

|

14 |

Poly(dimethylsiloxane) |

>99 |

<1 |

[a] Conditions: 1 a (200.0 mg, 2.78 mmol with respect to the monomer unit), polymer B (2.78 mmol with respect to the monomer unit), Zn(OAc)2 (5.1 mg, 1.0 mol%, 0.0278 mmol with respect to the monomer unit of 1), MeOH (6.0 g, 187.3 mmol, 67.5 equiv. with respect to monomer unit of 1), temperature: 160 °C (microwave heating), time: 5 min. [b] The yield of 2 bases on 1H NMR spectroscopy. The amount of substance of 2 was linked to the amount of substance of PLA. [c] The yield was determined by 1H NMR for depolymerization product(s) of the additional polymer. [d] Bisphenol A and dimethylcarbonate.

Next the depolymerization product 2 was applied as starting material for the resynthesis of polymer 1 (Table 4). In this regard, a mixture of methyl lactate and catalytic amounts of Zn(OTf)2 was heated at 130 °C for 24 hours (Table 1, entry 2). After cooling to ambient temperature an aliquot was taken for determination of the yield/conversion by 1H NMR analysis. The existence of the polymerization product 1 b was proven by the presence of a multiplet at δ = ∼5.10 ppm, which corresponds to the CH3CHO‐functionality of the polymer, while the CH3CHO‐functionality of the monomer can be detected at δ = 4.28 ppm (vide supra). Additionally, a quartet was observed at δ = 5.02 ppm (J=6.66 Hz, 1H, CH3CH‐), which corresponds to L‐lactide (3). [15] In consequence a conversion of 90 % and a NMR yield of 85 % of 1 b and 5 % of 3 was calculated. Moreover, a number average molecular weight (Mn) of ∼4614 g/mol was calculated based on the end‐groups of the PLA. In addition, different zinc(II) salts were tested as catalysts (Table 4, entries 3–5). Good yields 69–70 % for 1 b with Mn 576‐1243 g/mol and 2–15 % for 3 were observed for all zinc salts, while in the absence of any zinc source no product formation was noticed (Table 4, entry 1). Reducing the loading of the catalyst revealed a decrease of product yield accompanied by an increase of lactide formation (Table 4, entries 7–10). Increasing the reaction time revealed the formation of a higher molecular weight PLA (Mn ∼8970 g/mol) (Table 4, entry 11). Moreover, at lower temperature a reduced yield was noticed (Table 4, entry 13).

Table 4.

Polymerization of 2 using zinc catalysis – optimization of reaction conditions.[a]

|

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entry |

Catalyst |

Catalyst loading [mmol] |

T [°C] |

t [h] |

Conv. 2 [%][b] |

Yield 3 [%][b] |

Yield 1 b [%][b] |

Mn (1 b) [g/mol][c] |

|

1 |

– |

– |

130 |

24 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

|

2 |

Zn(OTf)2 |

1.0 |

130 |

24 |

90 |

5 |

85 |

n ∼53.4; Mn ∼4614 |

|

3 |

ZnCl2 |

1.0 |

130 |

24 |

85 |

15 |

69 |

n ∼6.5; Mn ∼576 |

|

4 |

ZnBr2 |

1.0 |

130 |

24 |

79 |

9 |

70 |

n ∼14.2; Mn ∼1243 |

|

5 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

1.0 |

130 |

24 |

72 |

2 |

70 |

n ∼8.4; Mn ∼739 |

|

7 |

Zn(OTf)2 |

0.5 |

130 |

24 |

93 |

7 |

86 |

n ∼14.9; Mn ∼1295 |

|

8 |

Zn(OTf)2 |

0.1 |

130 |

24 |

83 |

15 |

68 |

n ∼8.7; Mn ∼762 |

|

9 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

0.5 |

130 |

24 |

67 |

5 |

62 |

n ∼3.5; Mn ∼319 |

|

10 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

0.25 |

130 |

24 |

35 |

<1 |

35 |

n ∼1.8; Mn ∼168 |

|

11 |

Zn(OTf)2 |

1.0 |

130 |

48 |

91 |

5 |

86 |

n ∼104.0; Mn ∼8970 |

|

12[d] |

Zn(OAc)2 |

1.0 |

111 |

24 |

69 |

10 |

59 |

n ∼10.3; Mn ∼904 |

|

13 |

Zn(OAc)2 |

1.0 |

80 |

24 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

‐ |

[a] Reaction conditions: 2 (1.92 mmol), catalyst (0–0.0192 mmol), 80–130 °C, 24–48 h. [b] The conversion was determined by 1H NMR. [c] Calculation based on 1H NMR data. [d] Toluene as solvent (2.0 mL).

Moreover, for plastic cups (1 a) a scale‐up reaction was carried out (Scheme 2). In more detail, the reaction was performed in accordance to the reaction conditions stated in Table 1 entry 15 by using 20.0 g of 1 a. After purification/isolation by distillation 25.7 g of 2 were isolated, which corresponds to a yield of 98 %. Next, the isolated compound 2 was subjected to the polymerization protocol. Two grams of 2 were reacted with catalytic amounts of Zn(OTf)2 at 130 °C for 24 hours. Polymer 1 b was obtained in 92 % NMR yield and lactide in 2 % NMR yield. In addition, the mixture of polymer 1 b and lactide (3) was reacted with catalytic amounts of Zn(OAc)2 at 210 °C and 6 mbar. As product lactide was isolated in 49 % yield (L‐lactide: 44 %). [16]

Scheme 2.

Scale‐up of end‐of‐life PLA depolymerization and polymerization of methyl lactate.

In summary, we have established an easy‐to‐adopt chemical recycling method for EoL poly(lactide) (PLA). In more detail, the method bases on the zinc‐catalyzed depolymerization of PLA applying methanol as depolymerization reagent to obtain methyl lactate as product. Noteworthy, as catalyst simple zinc salts are applied to realize excellent yields of 2 (>99 %) within short reaction times (10 min) under microwave heating. Applying Zn(OAc)2 as catalyst turnover frequencies up to ∼45000 h−1 were obtained. The principle of operation of the concept was successfully proven in the conversion of a variety of PLA goods. In a second part methyl lactate was reacted with zinc salts to generate new low molecular weight PLA. Here good performance was observed for Zn(OTf)2 with yields of 91 % and Mn ∼8970 g/mol. The synthesized PLA was converted to lactide by zinc catalyzed depolymerization. The lactide can be used to access high molecular weight PLA.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Universität Hamburg is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Prof. Dr. Axel Jacobi von Wangelin, Dr. Felix Scheliga and Dr. Dieter Schaarschmidt (all UHH) for general discussions and support.

E. Cheung, C. Alberti, S. Enthaler, ChemistryOpen 2020, 9, 1224.

References

- 1.Plastics are typically composed of polymers and often other substances e. g. fillers, plasticizers, colorants.

- 2.

- 2a. Zhang X., Fevre M., Jones G. O., Waymouth R. M., Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 839–885; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Mittal V., Renewable Polymers – Synthesis, Processing, and Technology, John Wiley & Sons, Salem, 2011; [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Yu L., Biodegradable Polymer Blends and Composites from Renewable Resources, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Groot W., Poly (Lactic Acid): Synthesis, Structures, Properties, Processing, And Applications, R. Auras, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Lim L. T., Auras R., Rubino M., Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008, 33, 820–852; [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Moon S. I., Lee C. W., Miyamoto M., Kimura Y., J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2000, 38, 1673–1679; [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Li H., Wang C. H., Bai F., Yue J., Woo H. G., Organometallics 2004, 23, 1411–1415; [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Dechy-Cabaret O., Martin-Vaca B., Bourissou D., Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 6147–6176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Yang J., Pan H. W., Li X., Sun S. L., Zhang H. L., Dong L. S. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 46183-46194; [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Wang D., Yu Y., Ai X., Pan H., Zhang H., Dong L., Polym. Adv. Technol. 2019, 30, 203–211; [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Hajighasemi M., Nocek B. P., Tchigvintsev A., Brown G., Flick R., Xu X., Cui H., Hai T., Joachimiak A., Golyshin P. N., Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 2027–2039; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Penkhrue W., Kanpiengjai A., Khanongnuch C., Masaki K., Pathom-Aree W., Punyodom W., Lumyong S., Prep. Biochem. 2017, 47, 730–738; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5e. Qi X., Ren Y., Wang X., Int. Biodegradation 2017, 117, 215–223; [Google Scholar]

- 5f. Beigbeder J., Soccalingame L., Perrin D., Benezet J.-C., Bergeret A., Waste Manage. 2019, 83, 184–193; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5g. Gil-Castell O., Badia J. D., Ingles-Mascaros S., Teruel-Juanes R., Serra A., Ribes-Greus A., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 158, 40–51; [Google Scholar]

- 5h. Badia J. D., Stromberg E., Kittikorn T., Ek M., Karlsson S., Ribes-Greus A., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 143, 9–19; [Google Scholar]

- 5i. Badia J. D., Gil-Castell O., Ribes-Greus A., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 137, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.See for mechanical recycling:

- 6a. Badia J. D., Ribes-Greus A., Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 84, 22–39; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Dhar P., Prodyut, Kumar R., Bhasney M. S. M., Bhagabati P., Kumar A., Katiyar V., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 14493–14508; [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Zhao P., Rao C., Gu F., Sharmin N., Fu J., J. Cleaner Prod. 2018, 197, 1046–1055; [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Beltran F. R., Ortega E., Solvoll A. M., Lorenzo V., de la Orden M. U., Martinez Urreaga J., J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 2142–2152. See for biodegradation: [Google Scholar]

- 6e. Ghorpade V. M., Gennadios A., Hanna M. A., Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 76, 57–61; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6f. Gil-Castell O., Badia J. D., Ingles-Mascaros S., Teruel-Juanes R., Serra A., Ribes-Greus A., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 158, 40–51; [Google Scholar]

- 6g. Satti S. M., Shah A. A., Marsh T. L., Auras R. , J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 3848–3857; [Google Scholar]

- 6h. Sedničková M., Pekařová S., Kucharczyk P., Bočkajd J., Janigová I., Kleinová A., Jochec-Mošková D., Omaníková L., Perďochová D., Koutný M., Sedlařík V., Alexy P., Chodák I., Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 434–442; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6i. Satti S. M., Shah A. A., Auras R., Marsh T. L., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 144, 392–400; [Google Scholar]

- 6j. Karamanlioglu M., Preziosi R., Robson G. D., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 137, 122–130; [Google Scholar]

- 6k. Pikon K., Czop M., Polish J. Environ. Studies 2014, 23, 969–973; [Google Scholar]

- 6l. Madhavan Nampoothiri K., Nair N. R., John R. P., Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8493–8501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cosate de Andrade M. F., Souza P. M. S., Cavalett O., Morales A. R., J. Polym. Environ. 2016, 24, 372–384. [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a.J. Aguado, D. P. Serrano, Feedstock Recycling of Plastic Wastes The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 1999;

- 8b. Lu X.-B., Liu Y., Zhou H., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 11255–11266; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Feghali E., Tauk L., Ortiz P., Vanbroekhoven K., Eevers W., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 179, 109241; [Google Scholar]

- 8d. Payne J., McKeown P., Jones M. D., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 165, 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Odelius K., Hoglund A., Kumar S., Hakkarainen M., Ghosh A. K., Bhatnagar N., Albertsson A.-C., Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1250–1258; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Tsuji H., Ikarashi K., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 85, 647–656; [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Makino K., Arakawa M., Kondo T., Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1985, 33, 1195–201; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9d. Tsuji H., Polymer 2002, 43, 1789–1796; [Google Scholar]

- 9e. Tsuji H., Yamada T., J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 87, 412–419; [Google Scholar]

- 9f. Song X., Wang H., Yang X., Liu F., Yu S., Liu S., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 110, 65–70; [Google Scholar]

- 9g. Iñiguez-Franco F., Auras R., Dolan K., Selke S., Holmes D., Rubino M., Soto-Valdez H., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 149, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Petrus R., Bykowski D., Sobota P., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5222–5235; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Roman-Ramirez L. A., Mckeown P., Jones M. D., Wood J., ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 409–416; [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Liu M., Guo J., Gu Y., Gao J., Liu F., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 15127–15134; [Google Scholar]

- 10d. Zaitsev K. V., Cherepakhin V. S., Zherebker A., Kononikhin A., Nikolaev E., Churakov A. V., J. Organomet. Chem. 2018, 875, 11–23; [Google Scholar]

- 10e. Leibfarth F. A., Moreno N., Hawker A. P., Shand J. D., J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2012, 50, 4814–4822; [Google Scholar]

- 10f. Hirao K., Nakatsuchi Y., Ohara H., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 925–928; [Google Scholar]

- 10g. Bykowski D., Grala A., Sobota P., Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 5286–5289; [Google Scholar]

- 10h. Carné Sánchez A., Collinson S. R., Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 1970–1976; [Google Scholar]

- 10i. Plichta A., Lisowska P., Kundys A., Zychewicz A., Dębowski M., Florjańczyk Z., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 108, 288–296; [Google Scholar]

- 10j. Alberti C., Damps N., Meißner R. R. R., Enthaler S., ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 6845–6848; [Google Scholar]

- 10k. Alberti C., Damps N., Meißner R. R. R., Hofmann M., Rijono D., Enthaler S., Adv. Sus. Sys. 2020, 4, 1900081; [Google Scholar]

- 10l. Hofmann M., Alberti C., Scheliga F., Meißner R. R. R., Enthaler S., Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 2625–2629; [Google Scholar]

- 10m. Alberti C., Kricheldorf H. R., Enthaler S., ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12313–12316; [Google Scholar]

- 10n. Kindler T.-O., Alberti C., Fedorenko E., Santangelo N., Enthaler S., ChemistryOpen 2020, 9, 401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Calhorda M. J., Dagorne S., Avilés T., ChemCatChem 2014, 6, 1357–1367; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Roman-Ramirez L. A., Mckeown P., Jones M. D., Wood J., ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 409–416; [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Carné Sánchez A., Collinson S. R., Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 1970–1976; [Google Scholar]

- 11d. Román-Ramírez L. A., McKeown P., Jones M. D., Wood J., ACS Omega 2020, 5, 5556–5564; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11e. McKeown P., Román-Ramírez L. A., Bates S., Wood J., Jones M. D., ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 5233–5238; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11f. Román-Ramírez L. A., Powders M., McKeown P., Jones M. D., Wood J., J. Polym. Environ. DOI: 10.1007/s10924-020-01824–6; [Google Scholar]

- 11g. Román-Ramírez L. A., McKeown P., Shah C., Abraham J., Jones M. D., Wood J., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 11149–11156; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11h. Payne J., McKeown P., Mahon M. F., Emanuelsson E. A. C., Jones M. D., Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 2381–2389. [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a. Dai L., Liu R., Si C., Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1777–1783; [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Tsuji H., Kondoh F., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 141, 77–83; [Google Scholar]

- 12c. Liu Y., Wei R., Wie J., Liu X., Prog. Chem. 2008, 20, 1588–1594; [Google Scholar]

- 12d. Jiang B., Tantai X., Zhang L., Hao L., Sun Y., Deng L., Shi Z., RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 50747–50755; [Google Scholar]

- 12e. Huang W., Qi Y., Cheng N., Zong X., Zhang T., Jiang W., Li H., Zhang Q., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 101, 18–23; [Google Scholar]

- 12f. Tsuneizumi Y., Kuwahara M., Okamoto K., Matsumura S., Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. De Clercq R., Dusselier M., Poleunis C., Debecker D. P., Giebeler L., Oswald S., Makshina E., Sels B. F., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 8130–8139; [Google Scholar]

- 13b. De Clercq R., Dusselier M., Makshina E., Sels B. F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 3074–3078; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13c. Jeon B. W., Lee J., Kim H. S., Cho D. H., Lee H., Chang R., Kim Y. H., J. Biotechnol. 2013, 168, 201–207; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13d. Upare P. P., Hwang Y. K., Chang J.-S., Hwang D. W., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 4837–4842. [Google Scholar]

- 14.For further investigations Zn(OAc)2 (∼295 €/mol) was used, due to the lower price compared to Zn(OTf)2 (∼1796 €/mol).

- 15.Compared with an authentic sample.

- 16.See for instance:

- 16a. Zhang Y., Qi Y., Yin Y., Sun P., Li A., Zhang Q., Jiang W., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 2865–2873; [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Jiang B., Tantai X., Zhang L., Hao L., Sun Y., Deng L., Shi Z., RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 50747–50755; [Google Scholar]

- 16c. Noda M., Okuyama H., Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 47, 467–471 and references therein. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary