Abstract

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disorder with high incidence and mortality, is leading its way to the top of the list of the deadliest diseases without an effective disease-modifying drug. Ca2+ dysregulation, specifically abnormal release of Ca2+ via over activated ryanodine receptor (RyR), has been increasingly considered as an alternative upstream mechanism in AD pathology. Consequently, dantrolene, a RyR antagonist and FDA approved drug to treat malignant hyperthermia and chronic muscle spasms, has been shown to ameliorate memory loss in AD transgenic mice. However, the inefficiency of dantrolene to pass the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB) and penetrate the Central Nervous System needs to be resolved, considering its dose-dependent neuroprotection in AD and other neurodegenerative diseases. In this mini-review, we will discuss the current status of dantrolene neuroprotection in AD treatment and a strategy to maximize its beneficial effects, such as intranasal administration of dantrolene.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dantrolene, treatment, intranasal, calcium, blood brain barrier

1. INTRODUCTION

Neuroprotective drugs with the potential to repair neuronal damage or promote neurogenesis have been increasingly investigated for the treatment of AD [1]. For example, drugs such as GM-1 gangliosides and gacyclidine, which inhibit abnormal Ca2+ influx, and methylprednisolone and carbamylated erythropoietin, which reduce neuroinflammation, have shown neuroprotective effects [2]. Nevertheless, almost all investigated drugs for AD treatment have yielded disappointing results in clinical trials [2, 3]. As Ca2+ dysregulation has been proposed as an alternative mechanism, researchers have been studying dantrolene as a potential therapeutic drug [4]. In this mini-review, we summarize the current status of dantrolene therapy in AD and strategies for optimizing its therapeutic effects while minimizing its long-term side effects.

2. PATHOLOGY OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

In the 1990s, the amyloid cascade hypothesis demonstrated that the deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) oligomers is the initial pathological event in AD, leading to the formation of amyloid plaques and degradation of the brain and memory [5]. Many research efforts aiming at eliminating amyloid plaques for correction of memory loss in AD have failed [3]. For instance, a recent phase III clinical trial in 2018, conducted by Biogen using a drug called Aducanumab, targeting Aβ oligomers, has been terminated because it failed to decrease amyloid load [6, 7]. Interestingly, the trial was reinitiated because reanalysis of the original data demonstrated beneficial effects of Aducanumab at a higher dose. This example is one of many failed clinical trials [8]. Currently, developing drugs for AD include some secretase inhibitors and anti-Aβ vaccines which are also based on the amyloid cascade hypothesis that the production of amyloidogenic Aβ in the brain is neurotoxic and triggers neuron atrophy and ultimately leads to dementia [9]. The γ-secretase inhibitors such as Semagacestat and Avagacestat can reduce Aβ production in cultured neurons and in AD animals, while anti-Aβ vaccines increase Aβ clearance [10–12]. However, none of these amyloid based therapeutic approaches yielded efficacy in clinical trials. More importantly, patients who received Semagacestat treatment showed an increased risk of skin cancer, and therefore Phase III trials of Semagacestat were discontinued [13]. These unsatisfactory therapeutic outcomes of Semagacestat and other secretase inhibitors may suggest that the time for therapeutic intervention was too late or Aβ may not be the origin of the disease. Thus, there are urgent and enormous needs for the development of new anti-AD therapeutic agents that target the proximal route of the AD. After decades of research investigating new potential AD drug treatments, we have learned a lot more about the pathogenesis and mechanisms of AD. The recent effective treatment of AD cognitive dysfunction by dantrolene in various animal models suggests that Ca2+ dysregulation in AD plays an important role in AD pathology and cognitive dysfunction [14]. Although the extensive studies focused on the amyloid cascade hypothesis failed in developing a new drug, it has taught us a lot more about AD mechanisms and suggestions of alternative ways for AD treatment.

Metabolic processing of mutated Amyloid-β Precursor Protein (APP) is known to affect the function of RyR and lead to the formation of amyloid plaques, the defining marker of AD. Research work has shown that hydrolysis of APP generates oligomers and APP Intracellular Domains (AICD) [9], via the beta-secretase mediated amyloidogenic pathway [9]. Oligomer formation has been shown to decrease Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Ca2+ ([Ca2+]er) by creating channels on the ER membrane which allows [Ca2+]er to leak, thus, increasing the concentration of Ca2+ in cytosolic space ([Ca2+]c) and the mitochondria ([Ca2+]m) [9, 15, 16]. It should be noted that AD presenilin mutation and associated dysfunction has been demonstrated to cause the loss of normal presenilin function and reduce Ca2+ release from ER, resulting in increased [Ca2+]er concentration in the ER [9]. AICD was found to alter and induce the expression of crucial signaling genes such as RyR, a Ca2+ regulator and release channel on the ER membrane [9, 15–17]. Amounting evidence and data indicate that the dysregulation or overexpression of Ca2+ signaling influences the onset of AD [9, 15, 16]. Therefore, a drug that can inhibit the pathological Ca2+ signaling is proposed to be neuroprotective in AD.

In recent years, Ca2+ dysregulation has been increasingly recognized as an important mechanism of AD pathology and cognitive dysfunction [9, 16, 18]. Studies have found that Ca2+ dysregulation increases Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), impaired autophagy, neurodegeneration, synapse and cognitive dysfunction, and learning and memory deficits [19]. Evidence supporting Ca2+ dysregulation as the precursor to the neurodegenerative pathology and symptoms seen in AD has given the calcium hypothesis of AD widespread support [19]. The following drugs are currently being studied for their ability to correct Ca2+ dysregulation in AD [18]. Carvedilol, a RyR antagonist which stabilizes ER calcium signaling and is in phase IV clinical trial [20]; S18986, an AMPA receptor antagonist which regulates Ca2+ permeability and has been shown to be neuroprotective [21]. Nilvadipine [16], an L-type Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel (VGCC) antagonist that has shown to prevent Aβ accumulation and neurotoxicity when orally administered and is currently in phase III clinical trials [22]. The studies mentioned above show RyR as a target for treating AD. Dantrolene, a RyR antagonist and FDA approved drug to treat malignant hyperthermia and other chronic muscle spasms, etc. [23], has been investigated in several different AD animal models as a potential disease-modifying drug due to its ability to correct RyR [15, 24–26].

3. STUDIES USING DANTROLENE FOR AD TREATMENT

Considering the abnormally increased number of type-2 RyRs and function of RyRs in brains of AD patients or animals [25, 27], inhibition of dantrolene on the channel activation and opening [9] is expected to correct RyR-mediated calcium dysregulation and associated pathology of neurodegeneration, synapse structure damage and dysfunction as well as cognitive dysfunction [15, 25, 26]. Animal research studies that have used dantrolene for the treatment of AD have produced mixed results. In a study conducted by Zhang et al, double transgenic (APPPS1) and Wild Type (WT) mice were fed a 5mg/kg dantrolene solution twice a week from 2 to 8 months of age [26]. Their results indicated that long-term administration of dantrolene increased Aβ burden in APPPS1 vs. WT mice brains [26]. Unfortunately, this study did not investigate the effects of dantrolene on cognitive function. However, our laboratory and others have shown dantrolene to be neuroprotective in triple transgenic Alzheimer mice models (3xTg-AD) [24, 25, 28]. In one of our studies conducted by Peng et al. in 2012, mice of 2 to 5 months of age were treated intially with dantrolene through Intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection, then due to high mortality during the ICV administration, mice of 5 to 13 months of age received Subcutaneous (SQ) injections of dantrolene (5mg/kg) 3 times a week. After memory tests were conducted and the mice brains were analyzed, it was found that dantrolene improved memory in dantrolene treated 3xTg-AD mice in comparison to 3xTg-AD control mice. Additionally, dantrolene treated 3xTg-AD mice displayed decreased amyloid plaque levels in their brains when compared to control 3xTg-AD mice [25]. In a different study conducted by Oulès et al., in 2012, APP (swe)-expressing (Tg2576) mice received a SQ injection of dantrolene and PBS solution for 3 months. Their results showed that dantrolene decreased Aβ burden and ameliorated memory and learning deficits in dantrolene treated mice [24] (Table 1). Although there is not a significant amount of published papers that thoroughly investigate dantrolene therapy to treat AD, the current evidence shows its great potential. However, our studies along with several others have indicated that dantrolene is minimally efficient to penetrate into the CNS which is a limitation for trying to optimize its therapeutic effect in AD and other neurodegenerative diseases [24, 25, 29–31]. Given the research publications [24, 25, 28] discussed above, dantrolene has shown itself to be effective in treating AD; but the publications have failed to fully investigate the concentration and duration of dantrolene in the brain. In our recent study discussed below, we investigated whether intranasal dantrolene is more efficient when administered intranasally and is effective in treating AD as a disease-modifying drug [27, 32].

Table 1.

Studies investigating therapeutic effects of dantrolene in treating AD through different administration routes.

| Model Used | Administration Route | Dantrolene Brain Concentration | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3xTg-AD | ICV and SQ | ICV: 200–10,090 ng/g SQ: N/A |

Decreased memory loss, Improved memory learning, and reduced Aβ burden and plaque formation in the hippocampus. | [25] |

| Tg2576 | SQ | N/A | Decreased Aβ burden, senile plaque formation, and learning deficits. | [24] |

| APPPS1 | Oral | N/A | Increased amyloid load, loss of hippocampal excitatory synaptic markers, and neuronal atrophy. | [26] |

| 5XFAD | IN | SQ at 20 min: 110–150 ng/g IN at 20 min: 110–250 ng/g SQ at 60 min: 90–110 ng/g IN at 60 min: 150–260 ng/g |

Ameliorated memory loss, more effective than SQ, and did not change Aβ burden in comparison to control. | [32] |

Studies using various administration routes demonstrated mixed results. Most studies found that dantrolene is capable of improving memory, even if amyloid plaques did not change. There is a lack of animal studies that investigated neuroprotective concentrations of dantrolene in the brain relative to effectiveness.

Another benefit of using dantrolene for treatment of AD is due to its minimal side effects, even when it is administered for prolonged periods [29]. Some common side effects that have been reported are headaches, dizziness, drowsiness, anorexia, diarrhea, light-headedness, nausea and vomiting. Dantrolene has been shown to cause liver damage, but it is only attributed to chronic oral use at a high dose [29]. Scientists have been working to maximize effectiveness of dantrolene neuroprotection and minimize its side effects.

4. NEW APPROACH TO OPTIMIZE DANTROLENE NEUROPROTECTION

Intranasal administration of therapeutic drugs has been used to improve drug penetration into the CNS for agents that have limitations of passing the BBB [30, 33]. Due to dantrolene’s short half-life [23, 34], an improved administration method needs to be used for reaching a constant and elevated brain/plasma ratio [23]. Based on research indicating that dantrolene is dose-dependent [23–25, 29–31], the intranasal approach would be beneficial to cross the BBB and penetrate the CNS at an optimal concentration and duration [35].

Our recent study indicated that, compared to oral administration of dantrolene, intranasal approach provided significantly higher peak concentration and longer duration in the brain [36].

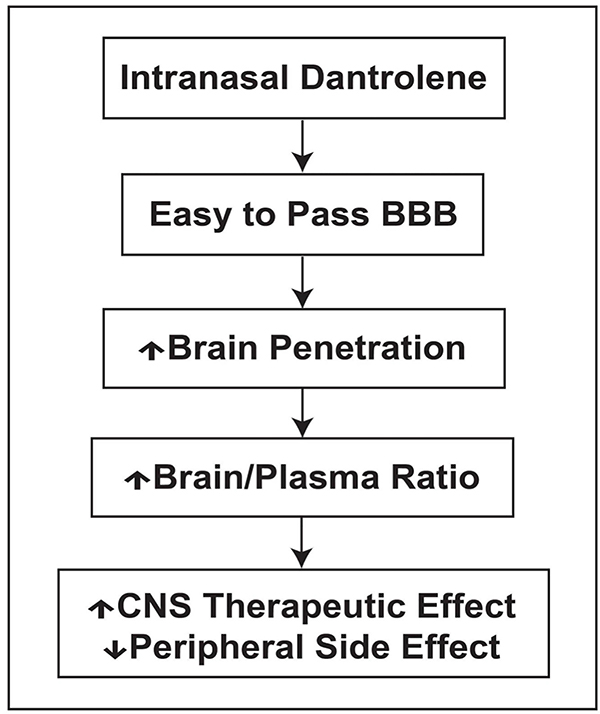

In our recent study [32], WT and 5XFAD mice were randomly assigned into 5 groups: Control, intranasal (IN), Vehicle, IN Dantrolene, SQ vehicle, and SQ Dantrolene. Additionally, the groups were divided into subgroups of early treatment, beginning at 2 months of age, and late treatment, beginning at 6 months of age. Additionally, we carried out various tests after treatments to examine motor, memory and smell functions. Our results suggest that in comparison to the oral approach, the intranasal administration of dantrolene significantly increased the concentration and duration in the brain [32] (Table 1). Intranasal dantrolene also achieved greater passage through the BBB and higher brain concentration than SQ administration [32]. Furthermore, intranasal dantrolene treated 5XFAD mice had an overall better effect than the SQ approach in ameliorating memory loss, even when treatment started after the full onset of AD pathology and cognitive dysfunction. Additionally, intranasal dantrolene after 9 months of treatment, produced tolerable side effects on liver structures and motor, smell and liver functions. Interestingly, it did not affect amyloid pathology significantly [32]. This new study suggests that intranasal administration of dantrolene may optimize the neuroprotective effects in the CNS and minimize its toxic effects in the peripheral system (Fig. 1). We are investigating and confirming the therapeutic effects and side effects of intranasal dantrolene in animal models more translational to AD patients before its clinical trials in patients.

Fig. (1). Intranasal dantrolene maximizes CNS therapeutics but minimizes peripheral side effects.

The increased dantrolene concentrations in CNS after intranasal administration yield effective therapeutic effects with a relatively lower dose and lower peripheral side effects.

Current studies on dantrolene show that it is neuroprotective but has limitations due to its poor permeability to access the CNS and BBB at effective concentrations. Although some studies indicated that dantrolene did not ameliorate Aβ deposition and plaque formation significantly [26, 32], it was still consistent in improving memory and cognitive function overall [24]. Our first study in which we administered dantrolene intranasally has shown to be significantly more effective in treating AD in comparison to the SQ approach. The intranasal dantrolene approach is strongly advised to optimize the treatment of AD but requires more investigation before clinical use.

Another approach to ameliorate RyR over activation mediated neuropathology in AD is the development of new RyR modulators and inhibitors, that have similar effects to dantrolene, but can pass the BBB easily and produce minimal side effects. It has been shown that S-107 can ameliorate protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of the RyR and inhibit pathological RyR calcium leakage, providing neuroprotection and ameliorating cognitive dysfunction in a FAD animal model [37] Ideally, it would be beneficial if these new compounds are able to pass the BBB easily and inhibit RyRs in the brain and associated pathology, with minimal side effects after chronic treatment in AD patients [38].

CONCLUSION

With disappointing failures on new effective drug development in Alzheimer’s disease focusing on amyloid pathology, it is the time to change the strategies in this research area. With its promising neuroprotective effects targeting upstream calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease, dantrolene, a clinically used muscle relaxant, has been repurposed to be a disease modifying drug for effective treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. The novel approach of intranasal administration of dantrolene, instead of commonly used oral approach, further increase dantrolene brain concentrations and durations not only strengthen its therapeutic effects but minimize its side effects.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This study was supported by grants from the NIH (R01GM084979, R01AG061447) to Huafeng Wei.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Huafeng Wei was once a member of the Advisory Board of Eagle Pharmaceutical Company for a one-day meeting in 2017 and the contract expired. Eagle Pharmaceutical Company produces and sells ryanodex, a new formula of dantrolene. Dr. Huafeng Wei is one of the inventors in a US provisional patent application entitled “Intranasal Administration of Dantrolene for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease” filed on June 28, 2019 (Serial number 62/868,820) by the University of Pennsylvania Trustee. The patent application is also part of the research collaboration agreement between the University of Pennsylvania and Eagle Pharmaceutical Company who makes and sells ryanodex, a new formula of dantrolene.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- [1].Rapid growth in neuroscience research: A study of neuroscience papers from 2006–2015 has revealed the most productive journals and contributing countries, and the most popular research topics [Internet]. ScienceDaily; 2019. [cited 23 June 2019]. Available from: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/04/170420093736.htm [Google Scholar]

- [2].Stocum D Regenerative medicine of neural tissues. Regen Biol Med 2012; 285–323. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schneider LS, Mangialasche F, Andreasen N, et al. Clinical trials and late-stage drug development for Alzheimer’s disease: An appraisal from 1984 to 2014. J Intern Med 2014; 275(3): 251–83. 10.1111/joim.12191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Khachaturian ZS. Calcium hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease and brain aging. Ann NY Acad Sci 1994; 747(1): 1–11. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44398.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Reitz C Alzheimer’s disease and the amyloid cascade hypothesis: A critical review. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2012; 2012: 369808 10.1155/2012/369808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer disease and aducanumab: Adjusting our approach. Nat Rev Neurol 2019; 15(7): 365–6. 10.1038/s41582-019-0205-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Feuerstein A. Biogen halts studies of closely watched alzheimer’s drug, a blow to hopes for new treatment. 2019 https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/biogen-halts-studies-of-closely-watched-alzheimers-drug-a-blow-to-hopes-for-new-treatment/?redirect=1.

- [8].Mullane K, Williams M. Alzheimer’s therapeutics: Continued clinical failures question the validity of the amyloid hypothesis-but what lies beyond? Biochem Pharmacol 2013; 85(3): 289–305. 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bezprozvanny I, Mattson MP. Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci 2008; 31(9): 454–63. 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Henley DB, May PC, Dean RA, Siemers ER. Development of semagacestat (LY450139), a functional γ-secretase inhibitor, for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2009; 10(10): 1657–64. 10.1517/14656560903044982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Coric V, van Dyck CH, Salloway S, et al. Safety and tolerability of the γ-secretase inhibitor avagacestat in a phase 2 study of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2012; 69(11): 1430–40. 10.1001/archneurol.2012.2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Dodart JC, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Peripheral anti-A beta antibody alters CNS and plasma A beta clearance and decreases brain A beta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98(15): 8850–5. 10.1073/pnas.151261398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Doody RS, Raman R, Farlow M, et al. A phase 3 trial of semagacestat for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(4): 341–50. 10.1056/NEJMoa1210951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liang L, Wei H. Dantrolene, a treatment for Alzheimer disease? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2015; 29(1): 1–5. 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang Y, Shi Y, Wei H. calcium dysregulation in alzheimer’s disease: A target for new drug development. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 2017; 7(5): 374 10.4172/2161-0460.1000374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tong BC, Wu AJ, Li M, Cheung KH. Calcium signaling in Alzheimer’s disease & therapies. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2018; 1865(11 Pt B): 1745–60. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Choi RH, Koenig X, Launikonis BS. Dantrolene requires Mg2+ to arrest malignant hyperthermia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017; 114(18): 4811–5. 10.1073/pnas.1619835114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Copenhaver PF, Anekonda TS, Musashe D, et al. A translational continuum of model systems for evaluating treatment strategies in Alzheimer’s disease: Isradipine as a candidate drug. Dis Model Mech 2011; 4(5): 634–48. 10.1242/dmm.006841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Berridge MJ. Calcium hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Physiol 2009; 459(3): 441–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang J, Ono K, Dickstein DL, et al. Carvedilol as a potential novel agent for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2011; 32(12): 2321.e1–2321.e12. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bloss EB, Hunter RG, Waters EM, Munoz C, Bernard K, McEwen BS. Behavioral and biological effects of chronic S18986, a positive AMPA receptor modulator, during aging. Exp Neurol 2008; 210(1): 109–17. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Salomone S, Caraci F, Leggio GM, Fedotova J, Drago F. New pharmacological strategies for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Focus on disease modifying drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 73(4): 504–17. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04134.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Krause T, Gerbershagen MU, Fiege M, Weisshorn R, Wappler F. Dantrolene-a review of its pharmacology, therapeutic use and new developments. Anaesthesia 2004; 59(4): 364–73. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Oulès B, Del Prete D, Greco B, et al. Ryanodine receptor blockade reduces amyloid-β load and memory impairments in Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Neurosci 2012; 32(34): 11820–34. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0875-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Peng J, Liang G, Inan S, et al. Dantrolene ameliorates cognitive decline and neuropathology in Alzheimer triple transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett 2012; 516(2): 274–9. 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang H, Sun S, Herreman A, De Strooper B, Bezprozvanny I. Role of presenilins in neuronal calcium homeostasis. J Neurosci 2010; 30(25): 8566–80. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1554-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu Z, Yang B, Liu C, et al. Long-term dantrolene treatment reduced intraneuronal amyloid in aged Alzheimer triple transgenic mice. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2015; 29(3): 184–91. 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chakroborty S, Briggs C, Miller MB, et al. Stabilizing ER Ca2+ channel function as an early preventative strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 2012; 7(12): e52056 10.1371/journal.pone.0052056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Muehlschlegel S, Sims JR. Dantrolene: Mechanisms of neuroprotection and possible clinical applications in the neurointensive care unit. Neurocrit Care 2009; 10(1): 103–15. 10.1007/s12028-008-9133-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hanson LR, Frey WH II. Intranasal delivery bypasses the blood-brain barrier to target therapeutic agents to the central nervous system and treat neurodegenerative disease. BMC Neurosci 2008; 9(3): S5 10.1186/1471-2202-9-S3-S5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang L, Andou Y, Masuda S, Mitani A, Kataoka K. Dantrolene protects against ischemic, delayed neuronal death in gerbil brain. Neurosci Lett 1993; 158(1): 105–8. 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90623-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shi Y, Zhang L, Gao X, et al. Intranasal dantrolene as a disease-modifying drug in Alzheimer 5XFAD mice. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2019; 15(7): 597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xiao C, Davis FJ, Chauhan BC, et al. Brain transit and ameliorative effects of intranasally delivered anti-amyloid-β oligomer antibody in 5XFAD mice. J Alzheimers Dis 2013; 35(4): 777–88. 10.3233/JAD-122419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Haraschak JL, Langston VC, Wang R, et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of oral dantrolene in the dog. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2014; 37(3): 286–94. 10.1111/jvp.12089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Meredith ME, Salameh TS, Banks WA. Intranasal delivery of proteins and peptides in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. AAPS J 2015; 17(4): 780–7. 10.1208/s12248-015-9719-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wang J, Shi Y, Yu S, et al. Intranasal administration of dantrolene increased brain concentration and duration. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0229156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lacampagne A, Liu X, Reiken S, et al. Post-translational remodeling of ryanodine receptor induces calcium leak leading to Alzheimer’s disease-like pathologies and cognitive deficits. Acta Neuropathol. 2017; 134(5):749–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schrank S, McDaid J, Briggs CA, et al. Human-induced neurons from presenilin 1 mutant patients model aspects of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21(3) 1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]