Abstract

Patient characteristics have been linked to prevalence and quality of shared decision-making (SDM) behaviors across diverse studies of varied size and focus. We aim to evaluate the extent to which patient characteristics are associated with patient-rated SDM scores as measured by collaboRATE and whether or not collaboRATE varies at the provider group level. We used the 2017 California Patient Assessment Survey data set, which included adult patients of 153 California-based medical groups receiving services between January and October 2016. Mixed-effects logistic regression evaluated relationships between collaboRATE scores and patient characteristics. We analyzed 31 265 total survey responses. Among included covariates, patients’ health status, race, primary language, and mode of survey response were significantly associated with collaboRATE scores. Case-mix adjustment is common in healthcare quality measurement and can be useful in pay-for-performance systems. For those use cases, we recommend adjusting collaboRATE scores by patients’ age, health status, gender, race, and language spoken at home, and survey response mode. However, when case-mix adjustment is not required, we suggest highlighting observed disparities across diverse patient populations to improve attention to inequities in patient experience.

Keywords: communication, measurement, medical decision-making, patient feedback, patient satisfaction

Introduction

Shared decision-making (SDM) has been defined as “a process by which clinicians and patients make decisions together using the best available evidence about the likely benefits and harms of each option, and where patients are supported to arrive at informed preferences” (1,2). Shared decision-making has been demonstrated to improve decisional conflict, uncertainty, and knowledge of treatment options among disadvantaged patients (3) and has been suggested as a possible means of reducing health disparities (4). Shared decision-making has been shown to benefit underserved populations “more than those with higher literacy, education, and socioeconomic status” (3). Shared decision-making also improves knowledge and helps form informed preferences among a broader patient population (5). However, existing literature has also shown the prevalence and quality of SDM and related communication constructs to vary according to patient and clinician characteristics (6 –18), as well as organizational and system-level factors, including the extent to which SDM is included in medical training (19).

In studies assessing SDM and patient–clinician communication across patient characteristics, age, gender, race/ethnicity (including race concordance between patients and clinicians), health status, socioeconomic status (including poverty and proxy measures such as educational attainment and employment status), and English proficiency have each been identified as associated with the prevalence and/or quality of SDM. Joseph-Williams’s 2014 systematic review (13) reports age as a barrier to SDM with mixed findings as to whether it is older or younger age that is associated with lower SDM. Forcino et al (7), Tai-Seale et al (20), Xu and Wong (21), Barton et al (14), and Solberg et al (12) support Joseph-Williams et al’s (13) earlier systematic review, with Forcino et al (7) and Tai-Seale et al (20) finding slightly higher SDM reports by older patients, while Barton et al (14), Solberg et al (12), and Xu and Wong (21) find poorer SDM among older age groups. Forcino et al (7) and Tai-Seale et al (20) also identify gender as a significant predictor of patient-reported SDM, with women more likely than men to provide high SDM ratings.

With regard to race and SDM, Cooper-Patrick et al (10) report that African American patients experienced less participatory healthcare visits than their white counterparts, a finding which was moderated by race concordance between patient and clinician. Both Joseph-Williams et al (13) and Solberg et al (12) found poor health status to be associated with poorer SDM. Lower socioeconomic status has also been demonstrated to predict poorer SDM, with proxies including limited educational attainment associated with poorer SDM in studies by Xu and Wong (21), Joseph-Williams et al (13), and Peek et al (15), patient employment associated with higher SDM in the study by Menear et al (6), and receipt of government financial assistance predicting lower SDM in the study by Xu and Wong (21). Poverty itself was associated with lower SDM in the study by Solberg et al (12). Finally, limited English proficiency was associated with poorer SDM in studies by Barton et al (14), Suurmond and Seeleman (18), Mosen et al (8), and Morales et al (9). Because of these previously identified associations between SDM and patient characteristics, each of these characteristics was represented in the current analysis to replicate those prior studies and determine whether those relationships hold in a large California-based sample. As the largest routinely collected generic (ie, not specific to a certain type of medical decision) SDM measurement effort to date, this study has the potential to further elucidate relationships between patient characteristics and SDM in a large and diverse sample.

Given the promise of SDM in improving health outcomes and reducing disparities (3,4), SDM is increasingly emphasized in clinical practice. This emphasis also translates to medical education, where 75% of medical students report training in SDM (23). Efforts to measure SDM have therefore increased (24), demonstrated by the development of collaboRATE, a 3-item patient-reported measure of SDM (22). CollaboRATE measures the 3 core dimensions of SDM including (1) information provision by clinician to patient, (2) patient preference elicitation, and (3) patient preference integration (22). However, existing SDM literature does not adequately address when and how to appropriately account for differences in patient characteristics, or “case mix,” when measuring and reporting on patients’ SDM experience. Without controlling for patient characteristics, one might obtain highly inaccurate estimates of the relationship of provider characteristics to outcomes because, for example, certain types of providers may be more likely to treat the most severely ill patients. Despite much existing research investigating relationships between certain patient characteristics and SDM, this is the first study to use a large patient survey sample to concurrently investigate the association between patient characteristics and patient-reported SDM measured by collaboRATE in order to inform an appropriate case-mix adjustment strategy. This information would be particularly helpful in applications related to provider performance measurement and incentivization of SDM, which are becoming increasingly common in United States value-based healthcare payment systems such as the Merit-based Incentive Payment Program.

In this study, we aim to (1) replicate existing studies using a large patient survey sample to evaluate the extent to which patient-level characteristics are associated with patient-rated SDM scores as measured by collaboRATE, a brief patient-reported measure of SDM (22), and (2) inform an appropriate case-mix adjustment strategy for patient-reported collaboRATE data. Based on prior literature using collaboRATE to measure SDM (11,20), we hypothesized that collaboRATE scores would increase with patient age and be higher among female patients than male patients.

Methods

Data

This study involved secondary analysis of the 2017 California Patient Assessment Survey (PAS) data set. The PAS is an annual cross-sectional survey conducted by the Pacific Business Group on Health. Our use of the deidentified data set was approved by the Pacific Business Group on Health and deemed exempt from further ethics review by our institutional review board.

Participants

Per the PAS standard sampling procedure, participants included adult (18 years and older) patients with commercial health insurance coverage who received ambulatory healthcare services from one of 153 participating California-based medical groups between January and October 2016.

Survey Administration

The PAS administration procedure invites a random sample of eligible patients to complete the survey through a sequence of survey administration modes, beginning with e-mail invitations to complete the survey online, followed by mailing the survey, and finally offering telephone administration for prior nonrespondents. Questionnaire administration was offered in English, Spanish, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese languages. Surveys were administered between December 2016 and March 2017.

Measures

Of the 35 total items in the 2017 PAS, this study includes demographic items in addition to collaboRATE, a 3-item patient-reported measure of SDM. The collaboRATE items included: (1) How much effort did this doctor make to help you understand your health issues?; (2) How much effort did this doctor make to listen to the things that matter most to you about your health issues?; and (3) How much effort did this doctor make to include what matters most to you in choosing what to do next? CollaboRATE responses were given on a scale of 0, labeled “no effort was made,” to 10, labeled “every effort was made,” representing a minor adaptation of the original 0 to 9 scale in order to conform to the standard Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) 0 to 10 response scale. Table 1 summarizes all included measures.

Table 1.

Measures.

| Measure | Item(s) | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| collaboRATE (adapted from (22)) |

|

0 (No effort was made) to 10 (Every effort was made) |

| Age | What is your age? | 18 to 24; 25 to 34; 35 to 44; 45 to 54; 55 to 64; 65 to 74; 75 or older |

| General health status | In general, how would you rate your overall health? | Excellent; Very good; Good; Fair; Poor |

| Mental health status | In general, how would you rate your overall mental or emotional health? | Excellent; Very good; Good; Fair; Poor |

| Gender | Are you male or female? | Male; Female |

| Educational attainment | What is the highest grade or level of school that you have completed? | Eighth grade or less; Some high school, but did not graduate; High school graduate or GED; Some college or 2-year degree; 4-year college graduate; More than 4-year college degree |

| Race | What is your race? | White or Caucasian; Black or African American; Asian; Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander; American Indian or Alaska Native; Other |

| Hispanic or Latino origin | Are you of Hispanic or Latino origin or descent? | Yes, Hispanic or Latino; No, not Hispanic or Latino |

| Primary language | What language do you mainly speak at home? | English; Spanish; Some other language |

| Primary or specialty care | (From survey sample data) | PCP; Specialist |

| Mode of response | (From survey sample data) | Mail; Web; Phone |

| Medical group/clinic | (From survey sample data) | Anonymized medical group ID |

| Medical group size | Number of survey respondents in each medical group (per Patient Assessment Survey quotas) | Continuous numeric variable |

Analysis

Scoring

We used the top score approach to collaboRATE scoring (25). At the item level, we considered each response with the highest possible score of “10—Every effort was made” to be a top score. Overall collaboRATE top scores included responses for which all 3 items received the highest possible score of 10. This scoring approach has demonstrated validity in a prior evaluation of collaboRATE’s psychometric properties and is intended to mitigate the ceiling effects common to patient-reported experience measures (25). Unadjusted collaboRATE scores consist of the proportion of top scores over all responses. For illustrative purposes, we also present adjusted collaboRATE scores accounting for the following independent variables: care setting (primary vs specialty), survey administration mode, size of medical group, patient’s age, patient’s general and mental health status, patient’s gender, patient’s educational attainment, patient’s race, whether or not the patient is of Hispanic or Latino origin, patient’s primary language, and the medical group.

Patient characteristics: Relationship to collaboRATE top-box scores

We used mixed-effects logistic regression analysis to evaluate the relationship between collaboRATE top-box scores and patient characteristics. The regression included the following as fixed effects: care setting (primary vs specialty); survey response mode (mail, telephone, or online); medical group size, represented by the number of survey responses per medical group; patient’s age; patient’s general health status; patient’s mental health status; patient’s gender; patient’s educational attainment; patient’s race; whether or not the patient claimed Hispanic or Latino origin; and patient’s primary language. Reference groups for categorical variables were selected a priori and intended to facilitate interpretation of results. Including patient characteristics accounts for possible confounding of patient case mix with provider characteristics. We evaluated odds ratios and random-effects standard deviation estimates to understand the relationship between covariates (independent variables) and overall collaboRATE SDM scores (dependent variable). All analyses controlled for clustering by medical group by including it as a categorical predictor but treating its coefficients as random effects. The random-effects specification has the advantage of allowing the effects of any time invariant predictors to be estimated while still accounting for the clustering of data within medical groups in the determination of standard errors, p values, and confidence intervals. To evaluate the total effect of categorical predictors with more than 2 levels (eg, the 3-level survey mode variable), we used χ2 tests to simultaneously contrast each of the levels. We tested monotonicity in ordinal scale variables using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis exploring the interaction between patient age and general health status by adding an interaction term to the regression model described above. As this sensitivity analysis resulted in a statistically nonsignificant interaction term (p > .05), we used the original regression specification described above in presenting and discussing our results.

We used Stata 13 software for all statistical analysis. As most missingness on patient characteristic variables was observed in blocks, missing data on any collaboRATE or demographic items resulted in listwise exclusion from regression analysis. To account for multiple comparisons in our large data set, we adopted a stringent statistical significance threshold of α ≤ .01.

Patient and provider characteristics: collaboRATE item-level analysis

Replicating the analysis described above using the same fixed and random effects, we conducted mixed-effects logistic regression analysis with top-box scores for each of the 3 collaboRATE items as dependent variables and compared odds ratios and confidence intervals across models. Please see Supplemental Materials for results of item-level analysis.

Results

Participant Characteristics

We analyzed 31 265 total responses to the PAS, reflecting an overall survey response rate of 29.5%. Majorities of respondents were between the ages of 45 and 64 (61.7%), attended at least some college (81.3%), were white (63.5%), and spoke English at home (86.3%). Table 2 presents full demographic details for survey respondents.

Table 2.

Demographic Profile of Survey Respondents.

| Proportion of Participants | Number of Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (n = 31 265) | ||

| 18-24 | 2.7% | 847 |

| 25-34 | 8.8% | 2750 |

| 35-44 | 12.9% | 4041 |

| 45-54 | 22.9% | 7147 |

| 55-64 | 38.9% | 12 149 |

| 65-74 | 11.1% | 3477 |

| 75 or older | 2.7% | 854 |

| General health status (n = 31 039) | ||

| Excellent | 12.7% | 3953 |

| Very good | 33.7% | 10 447 |

| Good | 36.4% | 11 311 |

| Fair | 14.6% | 4526 |

| Poor | 2.6% | 802 |

| Mental health status (n = 31 096) | ||

| Excellent | 30.2% | 9393 |

| Very good | 35.0% | 10 888 |

| Good | 24.9% | 7753 |

| Fair | 8.5% | 2638 |

| Poor | 1.4% | 424 |

| Gender (n = 31 211) | ||

| Male | 38.2% | 11 936 |

| Female | 61.8% | 19 275 |

| Educational attainment (n = 30 934) | ||

| 8th grade or less | 2.3% | 714 |

| Some high school, but did not graduate | 3.0% | 935 |

| High school graduate or GED | 13.3% | 4126 |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 36.0% | 11 142 |

| 4-year college graduate | 20.8% | 6442 |

| More than 4-year college degree | 24.5% | 7575 |

| Racea (n = 29 725) | ||

| White or Caucasian | 63.5% | 18 860 |

| Black or African-American | 6.4% | 1892 |

| Asian | 14.3% | 4258 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1.6% | 467 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1.8% | 535 |

| Other | 16% | 4764 |

| Hispanic or Latino origin (n = 30 478) | ||

| Yes, Hispanic or Latino origin | 25.6% | 7804 |

| No, not Hispanic or Latino origin | 74.4% | 22 674 |

| Primary language (n = 29 979) | ||

| English | 86.3% | 25 867 |

| Spanish | 7.6% | 2262 |

| Some other language | 6.2% | 1850 |

| Specialty (n = 31 265) | ||

| Primary care patient | 53.2% | 16 627 |

| Secondary care patient | 46.8% | 14 638 |

a Multiple responses accepted.

Medical Group/Survey Characteristics and Overall collaboRATE Scores

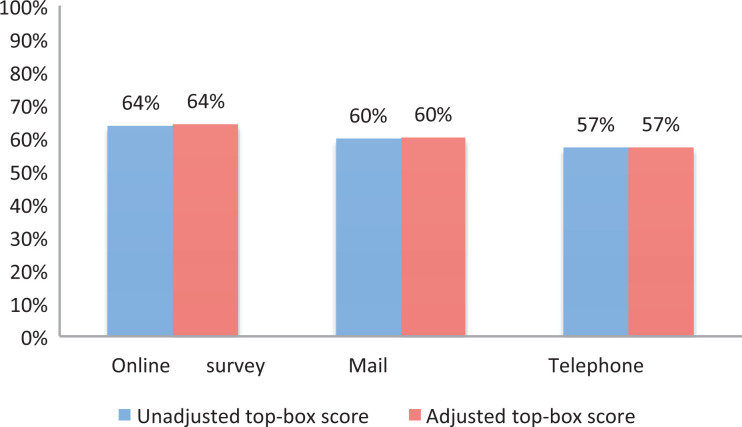

Among the included medical group and survey characteristics, only mode of survey response was significantly associated with collaboRATE scores (χ2 = 58.0, p < .001). Online survey responses had the highest collaboRATE scores, followed by mail and then phone. Online survey respondents (odds ratio [OR]: 1.226; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.148-1.310; p < .001) were 23% more likely than mail respondents to give a top collaboRATE score, and mail respondents were 10% more likely than phone respondents (OR: 0.903; 95% CI: 0.845-0.966; p = .003) to give a top collaboRATE score. The medical group-level standard deviation was 0.195 (95% CI: 0.160-0.236). Table 3 shows full regression results, and Figure 1 shows collaboRATE scores across survey administration modes.

Table 3.

Mixed-Effects Logistic Regression Results: Patient, Provider Characteristics, and collaboRATE Scores.

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Care setting | |

| Primary | (Reference category) |

| Specialty | 1.021 (0.972-1.074) |

| Survey administration | |

| (Reference category) | |

| Phone | 0.903 (0.845-0.966) |

| Web | 1.226 (1.148-1.310) |

| Medical group size | 1.000 (1.000-1.001) |

| Age | |

| 18-24 | (Reference category) |

| 25-34 | 1.036 (0.875-1.226) |

| 35-44 | 1.219 (1.036-1.434) |

| 45-54 | 1.370 (1.170-1.604) |

| 55-64 | 1.487 (1.274-1.737) |

| 65-74 | 1.739 (1.468-2.060) |

| 75+ | 1.768 (1.420-2.202) |

| General health status | |

| Excellent | (Reference category) |

| Very good | 0.649 (0.593-0.710) |

| Good | 0.534 (0.486-0.586) |

| Fair | 0.487 (0.436-0.544) |

| Poor | 0.462 (0.385-0.554) |

| Mental health status | |

| Excellent | (Reference category) |

| Very good | 0.673 (0.631-0.719) |

| Good | 0.558 (0.518-0.602) |

| Fair | 0.538 (0.484-0.598) |

| Poor | 0.444 (0.356-0.555) |

| Gender | |

| Male | (Reference category) |

| Female | 1.151 (1.093-1.213) |

| Educational attainment | |

| 8th grade or less | (Reference category) |

| Some high school | 0.972 (0.769-1.230) |

| High school graduate or GED | 0.986 (0.805-1.207) |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 0.860 (0.704-1.050) |

| 4-year college graduate | 0.638 (0.520-0.783) |

| More than 4-year college degree | 0.613 (0.500-0.752) |

| Race | |

| White or Caucasian | 1.022 (0.894-1.170) |

| Black or African-American | 1.203 (1.029-1.410) |

| Asian | 0.783 (0.677-0.906) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1.178 (0.943-1.471) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.934 (0.773-1.128) |

| Other | 0.999 (0.866-1.152) |

| Hispanic/Latino origin | |

| Hispanic or Latino | (Reference category) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 0.936 (0.864-1.014) |

| Primary language | |

| English | (Reference category) |

| Spanish | 0.774 (0.683-0.876) |

| Some other language | 0.806 (0.718-0.905) |

| Medical group: Standard deviation estimate (95% CI) | 0.195 (0.160-0.236) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1.

collaboRATE scores by mode of survey response.

Patient Characteristics and Overall collaboRATE Scores

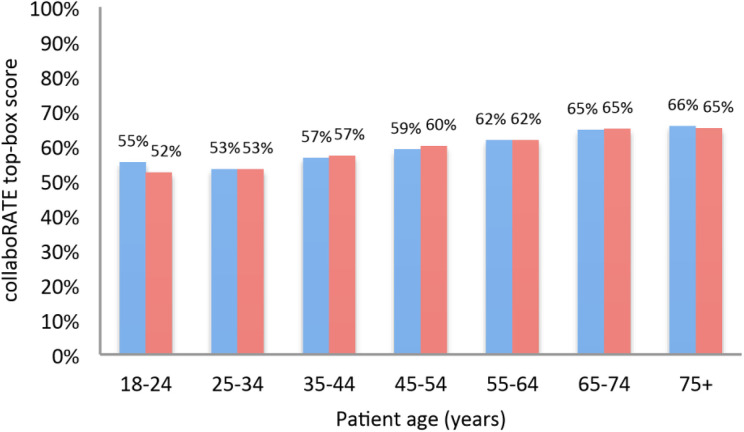

CollaboRATE scores significantly increased with patient age (χ2 = 137.6, p < .001). Compared to a reference group of 18- to 24-year-olds, 45- to 54-year-olds were 37% more likely to give top collaboRATE scores (OR: 1.370; 95% CI: 1.170-1.604; p < .001), 55- to 64-year-olds were 49% more likely to give top collaboRATE scores (OR: 1.487; 95% CI: 1.274-1.737; p < .001), 65- to 74-year-olds were 74% more likely to give top collaboRATE scores (OR: 1.739; 95% CI: 1.468-2.060; p < .001), and patients ages 75 and older were 77% more likely to give top collaboRATE scores (OR: 1.768; 95% CI: 1.420-2.202; p < .001). Figure 2 portrays collaboRATE scores by patient age-group.

Figure 2.

collaboRATE scores by patient age.

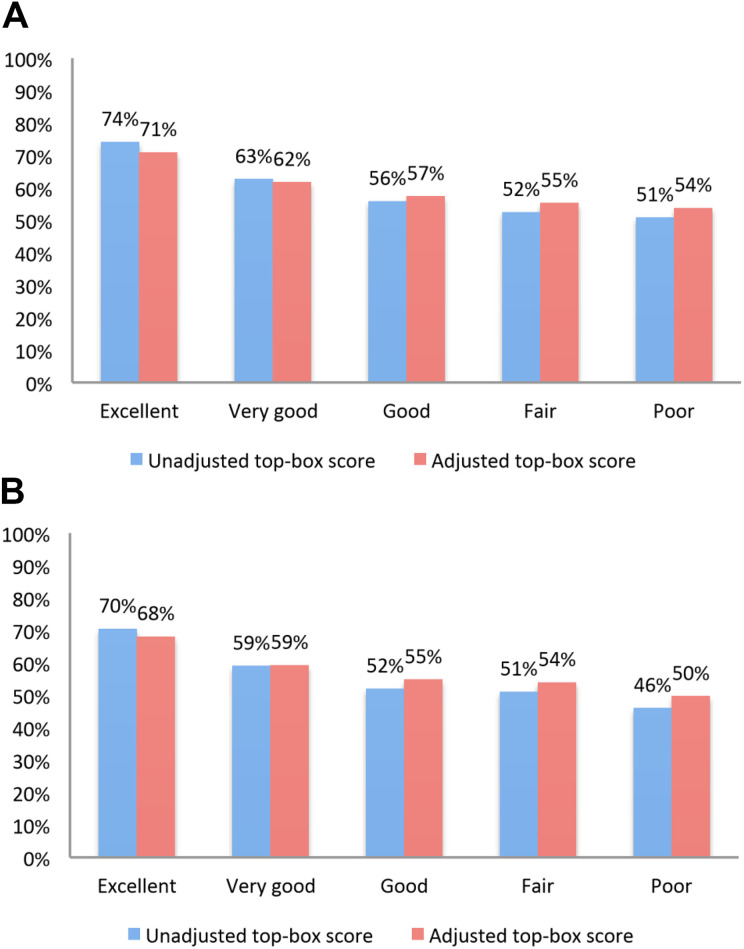

Health status was also significantly related to collaboRATE scores, with poorer general health associated with poorer collaboRATE ratings (χ2 = 572.1, p < .001). Compared to patients reporting excellent general health, patients reporting very good (OR: 0.649; 95% CI: 0.593-0.710; p < .001), good (OR: 0.534; 95% CI: 0.486-0.586; p < .001), fair (OR: 0.487; 95% CI: 0.436-0.544; p < .001), and poor (OR: 0.462; 95% CI: 0.385-0.554; p < .001) general health were all much less likely to give top collaboRATE scores. Similarly, poorer mental health was significantly associated with poorer collaboRATE ratings, with an overall difference in collaboRATE scores across the mental health categories (χ2 = 760.1, p < .001). Patients reporting very good (OR: 0.673; 95% CI: 0.631-0.719; p < .001), good (OR: 0.558; 95% CI: 0.518-0.602; p < .001), fair (OR: 0.538; 95% CI: 0.484-0.598; p < .001), and poor (OR: 0.444; 95% CI: 0.356-0.555; p < .001) mental health were much less likely than patients reporting excellent mental health to give collaboRATE top scores. Figure 3A and B shows collaboRATE scores by patients’ general and mental health status, respectively.

Figure 3.

A, collaboRATE scores by patient’s general health status. B, collaboRATE scores by patient’s mental health status.

Gender, educational attainment, race, and primary language were also significantly associated with collaboRATE scores. Women were 15% more likely than men to give collaboRATE top scores (highest possible responses; OR: 1.151; 95% CI: 1.093-1.213; p < .001). Compared to patients with eighth grade educational attainment or less, 4-year college graduates were 36% less likely to give top collaboRATE scores (OR: 0.638; 95% CI: 0.520-0.783; p < .001) and patients with more than a 4-year college degree were 39% less likely to give top collaboRATE scores (OR: 0.613; 95% CI: 0.500-0.752; p < .001). However, we observed only a very small overall negative correlation between education and collaboRATE score (ρ = −0.04, p < .001). Across racial groups, only responses from Asian patients had statistically significant associations with collaboRATE scores when compared to responses from all non-Asian patients (including those of white, black/African-American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, or other race). Asian survey respondents were 22% less likely than non-Asian respondents to give a top collaboRATE score (OR: 0.783; 95% CI: 0.677-0.906; p = .001). Finally, compared to patients who speak English at home, patients who speak Spanish (OR: 0.774; 95% CI: 0.683-0.876; p < .001) or some other language (OR: 0.806; 95% CI: 0.718-0.905; p < .001) at home were both less likely to give collaboRATE top scores. Figure 4A and B shows unadjusted and adjusted collaboRATE scores, respectively, across patient characteristics.

Figure 4.

A, Unadjusted collaboRATE scores by patient characteristics. B, Adjusted collaboRATE scores by patient characteristics.

Discussion

Key Findings

Even while controlling for patient and survey characteristics, we observed moderate variation at the provider group level as evidenced by the random-effect standard deviation of 0.195. This standard deviation approximately equates to a 95% confidence interval for the probability of obtaining a top collaboRATE score around a base probability of 0.56 (0.46-0.65). Thus, when everything but the provider is fixed, the difference in the probability of a top-box score being obtained for the provider at the 97.5th percentile and the provider at the 2.5th percentile is approximately 0.19. This sizable effect implies that there is substantial heterogeneity between providers in the likelihood of receiving a top-box score that is not explained by observed factors.

In analysis adjusting for available provider-level characteristics, several patient characteristics were associated with top collaboRATE scores (highest possible SDM scores) including age, health status, gender, race, and language spoken at home. Younger patients gave lower collaboRATE scores than their older counterparts. Patients reporting excellent general and mental health gave higher scores than those in poorer health. On average, men gave lower collaboRATE scores than women. Patients reporting Asian race and patients speaking a language other than English at home were more likely than others to give low collaboRATE scores. In addition, mode of survey response was associated with collaboRATE scores. Although telephone survey responses tended to yield lower scores than those returned via postal mail, Internet-based responses had more favorable scores than mailed responses.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, including its use of a large data set with SDM ratings from diverse patient populations across California. As a routinely administered survey used for performance measurement purposes, the PAS provides a unique look at routine and large-scale measurement of SDM. However, detailed information on clinicians and provider organizations was unavailable in this deidentified public data set; analysis of medical group characteristics was therefore very limited in this study. Our use of the number of survey responses as a proxy for medical group size assumes proportional sampling which may not have always been operationalized. Additionally, we lack observational data on SDM performance for the sample of clinical encounters rated in this study. We were therefore unable to strictly delineate differences in SDM behaviors across patient characteristics from other potential survey response biases. Finally, the fully California-based patient sample and 30% survey response rate may limit the generalizability of this study’s findings.

Results in Context

Our findings contribute additional insight into the role of patient and provider characteristics in SDM measurement among a large patient sample in a routine survey setting. This study finds evidence confirming existing literature with regard to less SDM reported by patients in poorer health (12,13). Interestingly, this relationship between poorer health and poorer collaboRATE scores was statistically significant despite controlling for patient age, where we saw older patients provide higher collaboRATE scores than their younger counterparts. Although these findings initially appear to be in conflict, they may result from a cohort effect on patient age paired with an experiential effect related to health status. In a qualitative study of primarily older patients (average age of 65), Frosch and colleagues found that participants felt “compelled to…defer to physicians during clinical consultations,” possibly accounting for the less critical SDM ratings we observed among older patients in the current study (26). Additionally, poorer SDM and clinical communication among patients in poorer health is intuitive in that complex health needs can require more attention to decision-making and communication processes.

Our findings also support prior work demonstrating an association between limited English proficiency and poorer SDM (8,9,14,18). Although we do not have data specific to English proficiency in this study, we found that patients who speak a language other than English at home reported experiencing poorer SDM than those who speak English at home.

To our knowledge, this is the first US study to report a significant association between patient-reported SDM and Asian patient race as we observed lower collaboRATE scores among patients identifying as Asian. Further research exploring normative expectations of SDM (27) among Asian-American patients and clinicians would be helpful in better understanding this observed disparity in collaboRATE scores.

In contrast to other studies of SDM and clinical communication focused on patients’ racial identities (15,10), we did not find a significant difference in collaboRATE SDM scores reported by black or African-American patients compared to scores from those who are not black or African-American despite a sufficiently large sample to detect such differences (28). However, while Cooper-Patrick and colleagues found that African American patients rated their visits as “significantly less participatory than whites,” they also identified more participation among patients with race-concordant clinical relationships than among those whose race was different than that of their clinician (10). Although we lack detailed clinician-level data among this sample, race concordance is one possible explanation for our lack of significant findings that merits further investigation. Further mixed-methods research into SDM experience across patient and provider racial identities may help to elucidate these relationships.

Additionally, despite existing evidence for better SDM experience among patients with higher educational attainment (13,15,21), our findings depart from that prior literature as they suggest that patients with 4-year college degrees were least likely to give top collaboRATE scores.

Case-mix adjustment is common in healthcare quality measurement and “uses statistical models to predict what each [provider’s] ratings would have been for a standard patient or population, thereby removing from comparisons the predictable effects of differences in patient characteristics that are consistent across [providers]” (29). This adjustment can be useful in provider performance profiling and pay-for-performance systems. Indeed, Paddison et al suggest that case-mix adjustment for performance assessment often has a minimal impact on most provider scores but “may meaningfully improve measurement of performance for practices with less typical patient populations, discouraging practices from ‘cream-skimming’ by avoiding enrolling patients who could be seen as ‘hard to treat’” (30). Incentivizing “cream-skimming” behavior through lack of case-mix adjustment for provider performance measurement threatens to exacerbate the disparities that performance measurement seeks to highlight and ameliorate. Based on our analysis, for provider performance profiling use cases, we recommend adjusting collaboRATE scores by mode of survey administration as well as patient age, health status, gender, race, and language spoken at home.

However, unlike quality metrics based on biomarkers or patient-reported symptoms, SDM is a process that can be highly influenced by, and even dependent on, patient characteristics. Because SDM is defined by the clinician–patient interaction, it is unavoidably influenced by patients’ personal characteristics and dependent on clinicians’ skill in navigating healthcare conversations regardless of those characteristics. In fact, the possibility of “cream-skimming” implies that patient-reported estimates of SDM may hide even further inequities in the quality of SDM across patient groups (30). For this reason, we believe that many measurement use cases, such as quality improvement initiatives, do not require case-mix adjustment. In these situations where case-mix adjustment is not required, we suggest highlighting observed disparities and quantifying potential unobserved disparities in SDM across diverse patient populations to improve attention to inequities in patient experience that can have substantial downstream effects on patient outcomes. Further research evaluating the role of SDM in improving health disparities is therefore advised.

Conclusion

We found significant associations between collaboRATE scores and mode of survey administration, patient age, health status, female gender, Asian race, and language spoken at home. These observed relationships can be used for case-mix adjustment if indicated.

Supplemental Material

JPE_Supplemental_materials for Do collaboRATE Scores Reflect Differences in Perceived Shared Decision-Making Across Diverse Patient Populations? Evidence From a Large-Scale Patient Experience Survey in the United States by Rachel C Forcino, Marcus Thygeson, A James O’Malley, Marjan J Meinders, Gert P Westert and Glyn Elwyn in Journal of Patient Experience

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Grace Lin, MD, for facilitating PAS data access.

Author Biographies

Rachel C Forcino is research project coordinator at The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

Marcus Thygeson is chief Health Officer at Bind Benefits.

A James O’Malley is professor at The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice and the Department of Biomedical Data Science, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth.

Marjan J Meinders is senior researcher at the Scientific Center for Quality of Healthcare, Radboud University Medical Center.

Gert P Westert is professor and head of the Scientific Center for Quality of Healthcare, Radboud University Medical Center.

Glyn Elwyn is professor at The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

Authors’ Note: R.C.F., M.T., A.J.O., M.J.M., G.P.W., and G.E. contributed to design of the work. R.C.F., M.T., A.J.O., and G.E. contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. R.C.F. drafted the manuscript; M.T., A.J.O., M.J.M., G.P.W., and G.E. critically revised the manuscript. Our use of the deidentified data set was approved by the Pacific Business Group on Health and deemed exempt from further review by Dartmouth College’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (study #31002).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Glyn Elwyn is a developer of the collaboRATE measure; he is also an adviser to PatientWisdom, an organization which offers to collect collaboRATE data.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Rachel C Forcino  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9938-4830

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9938-4830

Glyn Elwyn  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0917-6286

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0917-6286

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Forcino RC, Yen RW, Aboumrad M, Barr PJ, Schubbe D, Elwyn G, et al. US-based cross-sectional survey of clinicians’ knowledge and attitudes about shared decision-making across healthcare professions and specialties. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Durand M-A, Carpenter L, Dolan H, Bravo P, Mann M, Bunn F, et al. Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Malaga G, editor PLoS One. 2014;9:e94670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. King JS, Eckman MH, Moulton BW. The potential of shared decision making to reduce health disparities. J Law Med Ethics. 2011;39:30–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Menear M, Garvelink MM, Adekpedjou R, Perez MMB, Robitaille H, Turcotte S, et al. Factors associated with shared decision making among primary care physicians: findings from a multicentre cross-sectional study. Heal Expect. 2018;21:212–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forcino RC, Barr PJ, O’Malley AJ, Arend R, Castaldo MG, Ozanne EM, et al. Using CollaboRATE, a brief patient-reported measure of shared decision making: results from three clinical settings in the United States. Heal Expect. 2018;21:82–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mosen DM, Carlson MJ, Morales LS, Hanes PP. Satisfaction with provider communication among Spanish-speaking Medicaid enrollees. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4:500–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morales LS, Cunningham WE, Brown JA, Liu H, Hays RD. Are Latinos less satisfied with communication by health care providers? J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:409–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282:583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barr PJ, Forcino RC, Thompson R, Ozanne EM, Arend R, Castaldo MG, et al. Evaluating CollaboRATE in a clinical setting: analysis of mode effects on scores, response rates and costs of data collection. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Solberg LI, Crain AL, Rubenstein L, Unützer J, Whitebird RR, Beck A. How much shared decision making occurs in usual primary care of depression? J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:291–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barton JL, Trupin L, Tonner C, Imboden J, Katz P, Schillinger D, et al. English language proficiency, health literacy, and trust in physician are associated with shared decision making in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1290–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Wilson SC, Chin MH. Race and shared decision-making: perspectives of African-Americans with diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ratanawongsa N, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Couper MP, Van Hoewyk J, Powe NR. Race, Ethnicity, and shared decision making for hyperlipidemia and hypertension treatment: the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making. 2010;30:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levinson W, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, Frankel RM, Kuby A, Bereknyei S, et al. “It’s not what you say…”: racial disparities in communication between orthopedic surgeons and patients. Med Care. 2008;46:410–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suurmond J, Seeleman C. Shared decision-making in an intercultural context: barriers in the interaction between physicians and immigrant patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scholl I, LaRussa A, Hahlweg P, Kobrin S, Elwyn G. Organizational- and system-level characteristics that influence implementation of shared decision-making and strategies to address them—a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tai-Seale M, Elwyn G, Wilson CJ, Stults C, Dillon EC, Li M, et al. Enhancing shared decision making through carefully designed interventions that target patient and provider behavior. Health Aff. 2016;35:605–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu RH, Wong EL. Involvement in shared decision-making for patients in public specialist outpatient clinics in Hong Kong. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:505–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elwyn G, Barr PJ, Grande SW, Thompson R, Walsh T, Ozanne EM. Developing CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of shared decision making in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yen RW, Barr PJ, Cochran N, Aarts JW, Légaré F, Reed M, et al. Medical students’ knowledge and attitudes towards shared decision making: results from a multinational cross-sectional survey. MDM P&P. 2019;4(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gärtner FR, Bomhof-Roordink H, Smith IP, Scholl I, Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH. The quality of instruments to assess the process of shared decision making: a systematic review. van Wouwe JP, editor. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barr PJ, Thompson R, Walsh T, Grande SW, Ozanne EM, Elwyn G. The psychometric properties of CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of the shared decision-making process. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frosch DL, May SG, Rendle KAS, Tietbohl C, Elwyn G. Authoritarian physicians and patients’ fear of being labeled “Difficult” among key obstacles to shared decision making. Health Aff. 2012;31:1030–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Politi MC, Dizon DS, Frosch DL, Kuzemchak MD, Stiggelbout A. Importance of clarifying patients’ desired role in shared decision making to match their level of engagement with their preferences Service design for Shared Decision-Making View project Shared Decision-Making in the ED View project. BMJ. 2013;347:f7066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wilson Van Voorhis CR, Morgan BL. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2007;3:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 29. O’Malley AJ, Zaslavsky AM, Elliott MN, Zaborski L, Cleary PD. Case-mix adjustment of the CAHPS® hospital survey. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:2162–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paddison C, Elliott M, Parker R, Staetsky L, Lyratzopoulos G, Campbell JL, et al. Should measures of patient experience in primary care be adjusted for case mix? Evidence from the English General Practice Patient Survey. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:634–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

JPE_Supplemental_materials for Do collaboRATE Scores Reflect Differences in Perceived Shared Decision-Making Across Diverse Patient Populations? Evidence From a Large-Scale Patient Experience Survey in the United States by Rachel C Forcino, Marcus Thygeson, A James O’Malley, Marjan J Meinders, Gert P Westert and Glyn Elwyn in Journal of Patient Experience