Abstract

Background

As the fight against the COVID-19 epidemic continues, medical workers may have allostatic load.

Objective

During the reopening of society, medical and nonmedical workers were compared in terms of allostatic load.

Methods

An online study was performed; 3,590 Chinese subjects were analyzed. Socio-demographic variables, allostatic load, stress, abnormal illness behavior, global well-being, mental status, and social support were assessed.

Results

There was no difference in allostatic load in medical workers compared to nonmedical workers (15.8 vs. 17.8%; p = 0.22). Multivariate conditional logistic regression revealed that anxiety (OR = 1.24; 95% CI 1.18–1.31; p < 0.01), depression (OR = 1.23; 95% CI 1.17–1.29; p < 0.01), somatization (OR = 1.20; 95% CI 1.14–1.25; p < 0.01), hostility (OR = 1.24; 95% CI 1.18–1.30; p < 0.01), and abnormal illness behavior (OR = 1.49; 95% CI 1.34–1.66; p < 0.01) were positively associated with allostatic load, while objective support (OR = 0.84; 95% CI 0.78–0.89; p < 0.01), subjective support (OR = 0.84; 95% CI 0.80–0.88; p < 0.01), utilization of support (OR = 0.80; 95% CI 0.72–0.88; p < 0.01), social support (OR = 0.90; 95% CI 0.87–0.93; p < 0.01), and global well-being (OR = 0.30; 95% CI 0.22–0.41; p < 0.01) were negatively associated.

Conclusions

In the post-COVID-19 epidemic time, medical and nonmedical workers had similar allostatic load. Psychological distress and abnormal illness behavior were risk factors for it, while social support could relieve it.

Keywords: Allostatic load, Anxiety, COVID-19, Depression, Medical worker, Stress, Well-being

Introduction

On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak was a global health emergency [1]. As of July 23, 2020, at 7:02 p.m. CEST, COVID-19 15,012,731 cases and 619,150 deaths had been reported [2]. Long-term exposure to COVID-19 as a life-threatening stressor has been reported to be associated with a variety of psychosocial problems and mental symptoms in medical workers, especially frontline doctors and nurses [3, 4, 5]. It has been posited that persistent distress over the long term leads to changes in the psychosocial stress response which could be determined by clinimetric criteria for quantifying these changes linked to detrimental health consequences [3, 6, 7].

The ability of a person's physiological systems to adjust to challenges and stressors, or allostasis, is a required element of a healthy performance [6]. However, the amassed outcomes of repeated, frequent adjustment to stressors throughout life course give rise to disequilibrium and imbalance of these same physiological systems, referred to as allostatic load. When environmental challenges exceed the individual ability to cope, allostatic overload might ensue [8]. Medical workers are often first-line fighters in the treatment of patients with COVID-19. On a daily basis, they experience different levels of risk and pressure with regard to being infected in their workplace [9], and they are exposed to long and distressing work shifts to satisfy health requirements, especially at the stage of insufficient personal protective medical equipment [10, 11]. Psychosocial distress and mental symptoms were reported at the early stage and the stage after the maximum point of COVID-19 epidemic in China [3], with individuals being exposed to a prolonged origin of distress which may exceed their coping skills [6, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15].

Social support [16], originating in multiple sources such as family, friends, colleagues, and the community, may be a beneficial factor for medical workers, reducing their psychological distress and allostatic overload [5]. However, at the stage of reopening society in China [17], there is a paucity of studies on the prevalence of allostatic load among medical workers and related risk factors. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large nationwide study devoted to medical workers at the stage of reopening society among the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesize that there is a higher prevalence of allostatic load, as reported by self-ratings, in medical workers compared to nonmedical workers.

Materials and Methods

Design, Subjects, and Procedure

This is a cross-sectional study based on an online survey conducted from June 25 to July 10, 2020 (see online suppl. material; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000511823 for all online suppl. material). This study was performed 22 weeks after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China [10]. This survey period paralleled the reopening stage after the maximum point of the COVID-19 epidemic in China [17, 18]; during the reopening stage, individuals gradually returned to normal life after the Wuhan lockdown, thus after a period of great distress.

Citizens aged at least 18 years were welcome to join in an online survey via the Wenjuanxing platform (https://www.wjx.cn/m/83506828.aspx), which was distributed on the Internet and the WeChat platform. The online examination included questions on sociodemographic and clinical variables. A math question (i.e., 93 − 7 = ?) was placed at the end to guarantee the quality and completeness of the questionnaire and reduce the risk completion of the survey in an irresponsible manner. Participants who had not completed the survey received from the online platform a warning on unanswered questions when they did the math question. The online platform also offered warnings to those who gave up, and it recorded the number of those who completed the questionnaire during the study period.

Measurements

Demographic Data

Age, sex, job classification (i.e., medical or nonmedical worker), marital status (i.e., married and unmarried), education (>9 and ≤9 years) [3], number of hours worked per week, years of working, and health status (i.e., good or very good condition, not bad but not good, very bad, or bad) were collected via ad hoc questions. Participants were also asked whether they had a history of physical diseases, hospitalization, allergies, or mental illnesses before COVID-19 and whether they were taking medication, whether they consumed substances, coffee, tea, or excessive alcohol, and whether they were current smokers. Stressors were collected via the PsychoSocial Index (PSI) [15], as was information on whether COVID-19 was an additional stressor for participants (the question was: “Do you consider whether COVID-19 is currently an additional source of stress for you in daily life?”)

Clinimetric Assessment of Allostatic Load

Clinimetric evaluation of allostatic load was determined by PSI, which is a 55-item sensitive index assessing stress and related psychological distress [15, 19]. PSI has 12 items on sociodemographic and clinical data and the remaining 43 items on 5 domains, i.e., stress (items 13–20 and 22–30), well-being (items 31–36), psychological distress (items 37–51), abnormal illness behavior (items 52–54), and quality of life (item 55). Well-being and quality of life can be merged into a global well-being score [6, 19]. Participants were sorted as having allostatic load if they had been exposed to a stressor, in terms of major life events or chronic persistent circumstances, and presented clinical manifestations of psychiatric/psychosomatic symptoms and/or impairment in social and occupational functioning and/or a decline in psychological well-being [13, 15, 19]. For the present study, stressors were assessed by items 13–30 and split into the following 3 categories: interpersonal (items 20 and 26), work (items 15, 23, and 24), and daily stress (items 13, 14, 16–19, 25, and 27–30). Items 15 and 16 were related to “current job change” and “economic difficulties”, respectively. The variable “unemployment/employment” was tested via items 21 and 23. In details, “unemployment” was defined when the answers to both items 21 (Do you have a job?) and 23 (Are you retired or student?) were “no.” And “employed/employment” was determined depending on whether the answer to items 21 (Do you have a job?) was “yes.”

Clinimetric Evaluation of Mental Status

A clinimetric assessment of mental status was performed using the Symptom Questionnaire (SQ) [20], a simple self-rating questionnaire that assesses clinical symptoms and well-being with a high sensitivity [20]. SQ has 92 items, with 68 assessing symptoms, and 24 antonyms of some of the symptoms that show well-being. The tool has 4 sub-scales, i.e., depression, anxiety, somatization, and hostility/irritability. For each scale, a higher score suggests more psychological distress [20].

Social Support Assessment

The Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) is a 10-item self-report instrument assessing the degree of individual social support over the past year [21]. It encompasses 3 subscales, i.e., subjective support (items 1 and 3–5), objective support (items 2, 6, and 7), and utilization of support (items 8–10). Subjective support means that people feel supported, cared for, and helped by family members, friends, and colleagues. Objective support means visible, practical, and direct support. The utilization of support refers to the level of social support applied. A higher score for each subscale suggests a higher degree of social support [16, 21].

Statistical Analyses

Medical workers were frontline doctors and nurses who worked in a hospital with patients, regardless of whether they were patients with COVID-19 or not, between January 23 and April 8, 2020 (i.e., from the start of the lockdown to the opening of Wuhan). Nonmedical workers were those who did not work in hospitals/medical institutions during the above time period [3].

A χ2 test was used to compare group differences in categorical variables. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare continuous variables. Subgroup analyses were performed for medical and nonmedical workers. Interactions of job classification and various characteristics were also evaluated using logistic regression analyses. Allostatic load was used as a dependent variable while independent variables were: age, sex, marital status, education, employment, current job change, economic difficulties, a good health status, number of hours worked per week, years of working, previous physical status before the epidemic, lifestyle factors, presence and number of psychiatric disorders before the epidemic, SQ, SSRS, and PSI domains (including stress, abnormal illness behavior, and global well-being).

In order to minimize the between-group selection bias and control for potential confounding factors (i.e., age, gender, education, employment, current job change, and economic difficulties), propensity score matching (PSM) was applied to match medical and nonmedical workers [19]. Multivariate conditional logistic regressions were performed to evaluate the associations of allostatic load with mental symptoms (i.e., anxiety, depression, somatization, hostility, and SQ total score), social support (i.e., objective support, subjective support, utilization of support, and SSRS total score), abnormal illness behavior, and global well-being. Three models were used. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for marital status, previous physical diseases before the epidemic, history of allergies, coffee or tea drinks, smoking status, alcohol consumption, number of hours worked per week, and years of working. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for anxiety, depression, insomnia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The formula used to diagnose allostatic load via the PSI [19] was: A1 (yes) + A2 (yes) + B1 (yes) and/or B2 (yes) and/or B3 (yes). A1 = yes if the sum of items 13–20 and 22–30 is ≥1 score. A2 = yes if the answer to item 33 is 1. B1 = yes if at least 2 of the items 37–51 are met. B2 = yes if the sum of items 31, 32, 35, and 36 is ≥1 score. B3 = yes if the total of items 24 and 25 is equal to 2.

All hypotheses were tested at a significance level of 0.05. Data analyses were performed via SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Sixteen of the 3,606 subjects nationwide (4.4/‰) who wrongly responded to the math question were excluded, and thus 3,590 were analyzed (see online suppl. material). Of them, 1,244 were medical workers (i.e., 54 doctors and nurses who volunteered in the Hubei medical service and directly contacted COVID-19 patients in Hubei at the initial stage of COVID-19; 137 doctors and nurses who directly contacted COVID-19 patients in their hospitals but not in the Hubei medical service; and 1,053 doctors and nurses who did not volunteer in Hubei but directly contacted patients, including asymptomatic COVID-19 patients) and 2,346 were nonmedical workers (see online suppl. material). Eight medical workers and 209 nonmedical workers were unemployed during our study. Unemployment of medical workers referred to resigning and waiting for a change of work unit; unemployment of nonmedical workers was due to being laid off because of the COVID-19 epidemic.

In unmatched samples, the prevalence of allostatic load in medical workers was 15.8% (197/1,244) and 20.7% (468/2,346) among nonmedical workers (χ2 = 9.11; p < 0.01). Similar results were found among the 3 different groups of medical workers (see online suppl. 3) and PSM samples adjusted for age, sex, and education (n = 1,192 per group; see online suppl. 4). No statistically significant difference between medical and nonmedical workers was observed via logistic regression with interactive items of job classification and each covariate (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics by job classification and allostatic load in unmatched samples

| Characteristic | Medical workers (n = 1,244) |

p value1 | Nonmedical workers (n = 2,346) |

p valuea | pinteractionb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| allostatic load | nonallostatic load | allostatic load | nonallostatic load | ||||

| Subjects | 15.8 (197) | 84.2 (1,047) | 20.0 (468) | 80.1 (1,878) | <0.01 | ||

| Age, years | 34.84±7.97 | 37.35±8.60 | <0.01 | 35.09±9.48 | 39.72±10.68 | <0.01 | 0.50 |

| Male sex | 26.4 (52) | 21.3 (223) | 0.11 | 39.3 (184) | 42.1 (790) | 0.28 | 0.06 |

| Married | 77.2 (152) | 79.6 (833) | 0.45 | 66.7 (312) | 76.6 (1,438) | <0.01 | 0.11 |

| Educational level >9 years | 97.0 (191) | 97.8 (1,024) | 0.47 | 85.3 (399) | 92.6 (1,738) | <0.01 | 0.38 |

| Employed | 99.0 (195) | 99.4 (1,041) | 0.37 | 87.2 (408) | 92.1 (1,729) | <0.01 | 0.96 |

| Current job change | 10.7 (21) | 7.0 (73) | 0.07 | 24.2 (113) | 13.0 (245) | <0.01 | 0.32 |

| Economic difficulties | 51.8 (102) | 16.6 (174) | <0.01 | 62.2 (291) | 21.1 (397) | <0.01 | 0.51 |

| Good health status | 32.0 (63) | 50.2 (526) | <0.01 | 29.9 (140) | 53.3 (1,000) | <0.01 | 0.27 |

| Time worked per week, h | 47.93±13.75 | 45.08±13.27 | 0.01 | 36.60±21.00 | 34.77±19.88 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Time worked, years | 12.05±8.05 | 14.12±9.18 | 0.01 | 13.25±9.54 | 17.7±11.05 | <0.01 | 0.21 |

| Previous physical status | |||||||

| History of physical diseases | 34.5 (68) | 26.1 (273) | 0.01 | 23.1 (108) | 21.9 (411) | 0.58 | 0.11 |

| History of hospitalization | 36.6 (72) | 42.2 (442) | 0.14 | 41.0 (192) | 42.6 (799) | 0.55 | 0.36 |

| History of allergies | 26.9 (53) | 23.7 (248) | 0.33 | 20.5 (96) | 17.8 (334) | 0.17 | 0.98 |

| Lifestyle factors | |||||||

| Taking medication | 28.4 (56) | 23.4 (245) | 0.13 | 23.9 (112) | 22.8 (429) | 0.62 | 0.34 |

| Taking recreational drugs | 0 (0.0) | 0.8 (8) | 0.62 | 2.8 (13) | 1.0 (18) | <0.01 | 0.05 |

| Current coffee or tea drinkers | 52.8 (104) | 53.7 (562) | 0.82 | 60.0 (281) | 64.1 (1,204) | 0.10 | 0.47 |

| Current smokers | 13.2 (26) | 7.3 (76) | 0.01 | 26.1 (122) | 18.0 (338) | <0.01 | 0.48 |

| Current alcohol drinkers | 25.9 (51) | 18.3 (192) | 0.01 | 36.1 (169) | 30.9 (580) | 0.03 | 0.33 |

| Previous psychiatric conditions | |||||||

| History of mental illness | 1.0 (2) | 0.5 (5) | 0.31 | 1.9 (9) | 0.4 (7) | <0.01 | 0.35 |

| History of anxiety | 15.2 (30) | 6.9 (72) | <0.01 | 12.8 (60) | 3.3 (62) | <0.01 | 0.06 |

| History of depression | 10.2 (20) | 4.0 (42) | <0.01 | 10.5 (49) | 2.2 (42) | <0.01 | 0.07 |

| History of insomnia | 13.7 (27) | 8.3 (87) | 0.02 | 12.6 (59) | 4.5 (84) | <0.01 | 0.06 |

| History of PTSD | 18.8 (37) | 6.8 (71) | <0.01 | 13.2 (62) | 3.5 (66) | <0.01 | 0.34 |

| Had at least one the above | 24.9 (49) | 13.2 (138) | <0.01 | 17.5 (82) | 7.1 (133) | <0.01 | 0.31 |

| Psychiatric conditions (n) | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.14 | ||||

| 0 | 75.1 (148) | 86.8 (909) | 82.5 (386) | 92.9 (1,745) | |||

| 1 | 7.6 (15) | 5.8 (61) | 3.6 (17) | 3.4 (64) | |||

| 2 | 6.6 (13) | 3.5 (37) | 3.0 (14) | 1.7 (32) | |||

| 3 | 4.6 (9) | 2.1 (22) | 4.1 (19) | 1.1 (20) | |||

| 4 | 6.1 (12) | 1.3 (14) | 4.9 (23) | 0.6 (12) | |||

| 5 | 0 (0) | 0.4 (4) | 1.9 (9) | 0.3 (5) | |||

| SQ | |||||||

| Anxiety | 14.08±6.02 | 6.55±5.59 | <0.01 | 13.51±6.03 | 5.97±5.55 | <0.01 | 0.86 |

| Depression | 14.38±5.99 | 6.50±5.55 | <0.01 | 13.93±6.09 | 6.19±5.56 | <0.01 | 0.60 |

| Somatization | 12.08±5.72 | 6.93±4.79 | <0.01 | 11.34±5.58 | 6.49±4.66 | <0.01 | 0.93 |

| Hostility | 12.18±5.83 | 6.02±5.32 | <0.01 | 12.04±5.76 | 5.60±5.23 | <0.01 | 0.52 |

| Total | 52.72±20.74 | 26.00±18.53 | <0.01 | 50.82±20.11 | 24.25±18.20 | <0.01 | 0.85 |

| SSRS | |||||||

| Objective support | 6.97±3.09 | 8.56±3.10 | <0.01 | 6.75±2.91 | 8.36±3.11 | <0.01 | 0.84 |

| Subjective support | 19.90±4.86 | 22.84±4.97 | <0.01 | 19.26±5.00 | 22.76±4.98 | <0.01 | 0.30 |

| Utilization of support | 6.57±1.95 | 7.65±1.97 | <0.01 | 6.60±2.01 | 7.38±2.02 | <0.01 | 0.07 |

| Total score | 33.45±8.00 | 39.04±8.13 | <0.01 | 32.61±8.05 | 38.49±8.09 | <0.01 | 0.66 |

| Factors from the PSI | |||||||

| Stress | 5.51±2.66 | 2.99±2.20 | <0.01 | 6.06±2.67 | 3.13±2.28 | <0.01 | 0.44 |

| Abnormal illness behavior | 3.44±2.44 | 1.51±1.92 | <0.01 | 3.41±2.37 | 1.73±1.93 | <0.01 | 0.68 |

| Global well-being | 3.80±1.55 | 7.02±1.59 | <0.01 | 3.87±1.66 | 7.11±1.58 | <0.01 | 0.46 |

Values are presented as means ± SD or percents (n).

Obtained from χ2 tests for categorical variables and 2-sample Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables.

Obtained from logistic regression models with interactive items of job classification and each covariate.

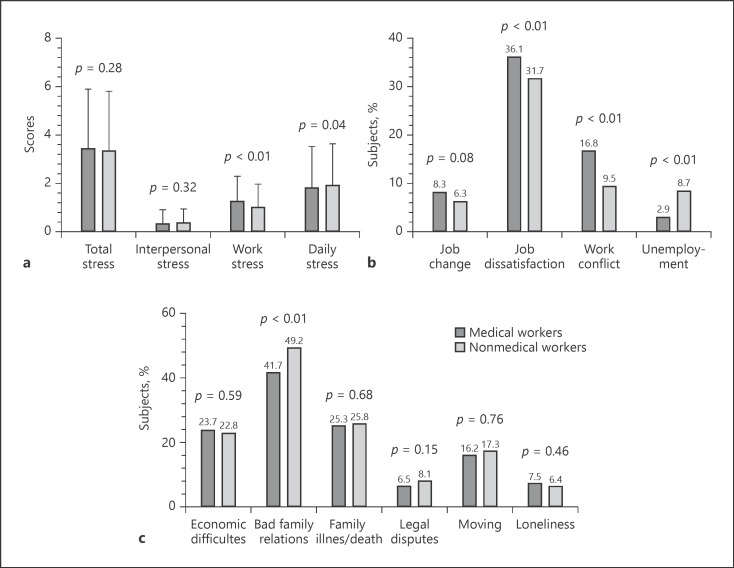

We further explored the differences in stressors between medical and nonmedical workers. Unmatched samples (1,222/1,244 vs. 2,344/2,346; p = 0.89) and each group of PSM (n = 1,138) believed that COVID-19 was a current additional origin of stress in their daily lives. In addition to COVID-19, medical workers had a higher score of work stress than nonmedical workers (p < 0.01; Fig. 1a), and especially a higher percentage of job dissatisfaction (36.1 vs. 31.7%; p < 0.01) and work conflict (16.8 vs. 9.5%; p < 0.01), while nonmedical workers had a higher rate of joblessness (8.7 vs. 2.9%; p < 0.01; Fig. 1b). For daily stress, nonmedical workers had a higher score than medical workers (p = 0.04; Fig. 1a); in particular, they had a higher rate of bad family relations (49.2 vs. 41.7%; p < 0.01; Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Allostatic load and its components in medical and nonmedical workers in PSM samples (n = 1,138). a Total stress and components. b Components of work stress. c Components of daily stress.

Table 2 shows comparisons of PSM samples, adjusting for age, sex, education, employment, current job change, and economic difficulties. Medical (n = 1,138) and nonmedical workers (n = 1,138) had no statistically significant difference in prevalence of allostatic load (15.8 vs. 17.8%; p = 0.22), while statistically significant differences were found for the following variables: marital status, previous physical diseases before the epidemic, personal history of allergies, coffee or tea drinking, smoking status, alcohol consumption, number of hours worked per week, years of working, personal history of anxiety, depression, insomnia, PTSD.

Table 2.

Comparison of propensity score-matched samples adjusted for age, sex, education, employment, job change, and economic difficulties

| Covariates | Medical workers (n = 1,138) |

Nonmedical workers (n = 1,138) |

p valuea | p valueb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| allostatic load | nonallostatic load | total | allostatic load | nonallostatic load | total | |||

| Subjects, n or % | 180 | 958 | 15.8 | 202 | 936 | 17.8 | 0.22 | − |

| Age, years | 35.30±8.14 | 37.88±8.70 | 37.47±8.66 | 33.49±8.17 | 38.70±9.70 | 37.77±9.65 | 0.54 | 0.05 |

| Male sex | 28.9 (52) | 23.3 (223) | 24.2 (275) | 23.3 (47) | 26.0 (243) | 25.5 (290) | 0.47 | 0.09 |

| Married | 78.9 (142) | 80.5 (771) | 80.2 (913) | 68.3 (138) | 76.1 (712) | 74.7 (850) | <0.01 | 0.27 |

| Educational level >9 years | 96.7 (174) | 97.6 (935) | 97.4 (1,109) | 96.0 (194) | 97.5 (913) | 97.3 (1,107) | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| Employed | 98.9 (178) | 99.4 (952) | 99.3 (1,130) | 99.0 (200) | 99.2 (929) | 99.2 (1,129) | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| Job changed currently | 11.7 (21) | 7.6 (73) | 8.3 (94) | 13.9 (28) | 4.7 (44) | 6.3 (72) | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Economic difficulties | 55.6 (100) | 17.8 (170) | 23.7 (270) | 53.5 (108) | 16.1 (151) | 22.8 (259) | 0.59 | 0.90 |

| Good health status | 31.7 (57) | 50.9 (488) | 47.9 (545) | 29.7 (60) | 53.3 (499) | 49.1 (559) | 0.56 | 0.44 |

| Time worked per week, h | 47.67±13.86 | 45.06±13.31 | 45.47±13.43 | 38.88±18.99 | 36.38±18.86 | 36.82±18.90 | <0.01 | 0.30 |

| Time worked, years | 12.45±8.26 | 14.65±9.31 | 14.30±9.18 | 11.27±8.11 | 16.55±10.24 | 15.61±10.09 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| Previous physical status | ||||||||

| History of physical diseases | 36.7 (66) | 26.8 (257) | 28.4 (323) | 26.2 (53) | 19.1 (179) | 20.4 (232) | <0.01 | 0.85 |

| History of hospitalization | 37.2 (67) | 41.4 (397) | 40.8 (464) | 44.6 (90) | 41.8 (391) | 42.3 (481) | 0.47 | 0.20 |

| History of allergies | 27.8 (50) | 23.6 (226) | 24.2 (276) | 23.3 (47) | 18.9 (177) | 19.7 (224) | 0.01 | 0.87 |

| Lifestyle factors | ||||||||

| Taking medication | 29.4 (53) | 23.6 (226) | 24.5 (279) | 24.3 (49) | 21.4 (200) | 21.9 (249) | 0.14 | 0.59 |

| Taking recreational drugs | 0 (0) | 0.8 (8) | 0.7 (8) | 2.5 (5) | 0.6 (6) | 1.0 (11) | 0.49 | 0.03 |

| Current coffee or tea drinkers | 53.3 (96) | 54.5 (522) | 54.3 (618) | 60.9 (123) | 62.8 (588) | 62.5 (711) | <0.01 | 0.88 |

| Current smokers | 13.3 (24) | 7.8 (75) | 8.7 (99) | 16.8 (34) | 11.2 (105) | 12.2 (139) | 0.01 | 0.71 |

| Current alcohol drinkers | 27.2 (49) | 19.2 (184) | 20.5 (233) | 27.7 (56) | 23.2 (217) | 24.0 (273) | 0.04 | 0.40 |

| Previous psychiatric conditions | ||||||||

| History of mental illness, | 1.1 (2) | 0.4 (4) | 0.5 (6) | 1.0 (2) | 0.5 (5) | 0.6 (7) | 0.78 | 0.76 |

| History of anxiety | 15.6 (28) | 6.6 (63) | 8.0 (91) | 12.4 (25) | 3.0 (28) | 4.7 (53) | <0.01 | 0.14 |

| History of depression | 10.0 (18) | 3.9 (37) | 4.8 (55) | 6.9 (14) | 2.1 (20) | 3.0 (34) | 0.02 | 0.65 |

| History of insomnia | 13.9 (25) | 8.1 (78) | 9.0 (103) | 10.9 (22) | 3.8 (36) | 5.1 (58) | <0.01 | 0.17 |

| History of PTSD | 18.9 (34) | 6.8 (65) | 8.7 (99) | 11.4 (23) | 2.8 (26) | 4.3 (49) | <0.01 | 0.36 |

| Had at least one of the above | 25.6 (46) | 12.8 (123) | 14.8 (169) | 16.8 (34) | 6.4 (60) | 8.3 (94) | <0.01 | 0.43 |

| Psychiatric conditions (n) | <0.01 | 0.14 | ||||||

| 0 | 74.4 (134) | 87.2 (835) | 85.2 (969) | 83.2 (168) | 93.6 (876) | 91.7 (1,044) | ||

| 1 | 7.8 (14) | 5.4 (52) | 5.8 (66) | 4.5 (9) | 3.4 (32) | 3.6 (41) | ||

| 2 | 7.2 (13) | 3.8 (36) | 4.3 (49) | 4.0 (8) | 1.3 (12) | 1.8 (20) | ||

| 3 | 5.0 (9) | 2.1 (20) | 2.6 (29) | 4.5 (9) | 1.0 (9) | 1.6 (18) | ||

| 4 | 5.6 (10) | 1.2 (12) | 1.9 (22) | 3.0 (6) | 0.3 (3) | 0.8 (9) | ||

| 5 | 0 (0) | 0.3 (3) | 0.3 (3) | 1.0 (2) | 0.4 (4) | 0.5 (6) | ||

| SQ | ||||||||

| Anxiety | 14.22±5.93 | 6.51±5.63 | 7.73±6.33 | 14.04±5.70 | 5.89±5.35 | 7.33±6.25 | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| Depression | 14.54±5.95 | 6.49±5.58 | 7.76±6.36 | 13.93±5.92 | 5.95±5.42 | 7.37±6.29 | 0.11 | 0.94 |

| Somatization | 12.12±5.65 | 6.92±4.82 | 7.75±5.31 | 11.52±5.24 | 6.31±4.45 | 7.24±5.01 | 0.04 | 0.29 |

| Hostility | 12.19±5.79 | 5.99±5.35 | 6.97±5.88 | 12.58±5.64 | 5.68±5.10 | 6.91±5.83 | 0.79 | 0.11 |

| Total | 53.08±20.38 | 25.92±18.69 | 30.21±21.39 | 52.07±18.93 | 23.84±17.39 | 28.85±20.7 | 0.16 | 0.13 |

| SSRS | ||||||||

| Objective support | 7.06±3.15 | 8.61±3.11 | 8.36±3.17 | 7.00±2.87 | 8.46±3.03 | 8.20±3.06 | 0.22 | 0.98 |

| Subjective support | 19.96±4.86 | 22.95±4.97 | 22.47±5.07 | 19.21±4.82 | 22.73±4.86 | 22.10±5.04 | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| Utilization of support | 6.54±1.98 | 7.63±1.99 | 7.45±2.02 | 6.66±2.10 | 7.55±1.95 | 7.40±2.00 | 0.31 | 0.45 |

| Total score | 33.55±8.06 | 39.18±8.16 | 38.29±8.39 | 32.87±8.15 | 38.74±7.88 | 37.70±8.24 | 0.12 | 0.61 |

| Factors from the PSI | ||||||||

| Stress | 5.64±2.65 | 3.02±2.20 | 3.44±2.47 | 5.62±2.59 | 2.92±2.17 | 3.40±2.48 | 0.64 | 0.80 |

| Abnormal illness behavior | 3.44±2.42 | 1.50±1.91 | 1.80±2.12 | 3.57±2.32 | 1.66±1.87 | 2.00±2.09 | 0.01 | 0.51 |

| Global well-being | 3.76±1.55 | 7.04±1.58 | 6.52±1.98 | 3.89±1.63 | 7.20±1.54 | 6.61±2.00 | 0.18 | 0.94 |

Values are presented as means ± SD or percents (n) unless otherwise stated.

Obtained to assess the covariate difference between medical workers and nonmedical workers from χ2 tests for categorical variables and 2-sample Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables.

Obtained from logistic regression models with interactive items of job classification and each covariate.

Multivariate conditional logistic regression for allostatic load risk in PSM samples, adjusted for age, sex, education, employment, job change, and economic difficulties, revealed that anxiety (OR = 1.24; 95% CI 1.18–1.31; p < 0.01), depression (OR = 1.23; 95% CI 1.17–1.29; p < 0.01), somatization (OR = 1.20; 95% CI 1.14–1.25; p < 0.01), hostility (OR = 1.24; 95% CI 1.18–1.30; p < 0.01), SQ total score (OR = 1.08; 95% CI 1.06–1.09; p < 0.01), and abnormal illness behavior (OR = 1.49; 95% CI 1.34–1.66; p < 0.01) were independent risk factors for allostatic load, while objective support (OR = 0.84; 95% CI 0.78–0.89; p < 0.01), subjective support (OR = 0.84; 95% CI 0.80–0.88; p < 0.01), utilization of support (OR = 0.80; 95% CI 0.72–0.88; p < 0.01), SSRS total score (OR = 0.90; 95% CI 0.87–0.93; p < 0.01), and global well-being (OR = 0.30; 95% CI 0.22–0.41; p < 0.01) were protective factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate conditional logistic regression for allostatic load risk in propensity score-matched samples adjusted for age, sex, education, employment, job change, and economic difficulties

| Social support and stress (continuous) | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Anxiety | 1.24 (1.19–1.30) | <0.01 | 1.25 (1.19–1.31) | <0.01 | 1.24 (1.18–1.31) | <0.01 |

| Depression | 1.22 (1.17–1.27) | <0.01 | 1.22 (1.17–1.28) | <0.01 | 1.23 (1.17–1.29) | <0.01 |

| Somatization | 1.20 (1.15–1.26) | <0.01 | 1.20 (1.15–1.26) | <0.01 | 1.20 (1.14–1.25) | <0.01 |

| Hostility | 1.24 (1.18–1.30) | <0.01 | 1.24 (1.18–1.31) | <0.01 | 1.24 (1.18–1.30) | <0.01 |

| SQ total score | 1.07 (1.06–1.09) | <0.01 | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | <0.01 | 1.08 (1.06–1.09) | <0.01 |

| Objective support | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | <0.01 | 0.85 (0.79–0.90) | <0.01 | 0.84 (0.78–0.89) | <0.01 |

| Subjective support | 0.85 (0.82–0.89) | <0.01 | 0.84 (0.80–0.89) | <0.01 | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | <0.01 |

| Utilization of support | 0.81 (0.74–0.88) | <0.01 | 0.81 (0.74–0.89) | <0.01 | 0.80 (0.72–0.88) | <0.01 |

| SSRS total score | 0.91 (0.89–0.93) | <0.01 | 0.91 (0.88–0.93) | <0.01 | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) | <0.01 |

| Abnormal illness behavior | 1.49 (1.35–1.65) | <0.01 | 1.49 (1.34–1.65) | <0.01 | 1.49 (1.34–1.66) | <0.01 |

| Global well-being | 0.32 (0.25–0.42) | <0.01 | 0.31 (0.23–0.41) | <0.01 | 0.30 (0.22–0.41) | <0.01 |

Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: additionally adjusted for marital status, number of hours worked per week, years of working, previous physical diseases before the epidemic, history of allergies, current coffee or tea consumption, smoking status, and current alcohol use. Model 3: additionally adjusted for anxiety, depression, insomnia, and PTSD.

Discussion

COVID-19 as a persistently life-threatening stressor brought psychological distress, even allostatic overload, on medical workers and nonmedical workers during the first stage of COVID-19 [3]. It also had other unprecedented global impacts [22]. However, much less is known about the prevalence of allostatic load after the reopening of society during COVID-19 in China. Our study first examined this occurrence among medical and nonmedical workers. Interestingly, the results showed that medical and nonmedical workers did not differ in allostatic load prevalence during the stage of reopening society in China, which was contrary to our hypothesis. Similarly, total stress scores did not differ in the 2 groups. Social support and global well-being were protective factors against allostatic load, while mental symptoms including anxiety, depression, somatization, hostility, SQ total score, and abnormal illness behavior were independent risk factors for allostatic load.

In our study, we further observed that, with the change of COVID-19 in China, although both medical and nonmedical workers still regarded COVID-19 as an additional stress in their lives and there were no differences in total stress score; they felt a different stress since they were probably exposed to different stressors. For medical workers, stressors from work included job dissatisfaction and work conflicts, while nonmedical workers had a higher percentage of joblessness. In addition, nonmedical workers had a higher daily stress than medical workers. In terms of daily stressors, nonmedical workers had prominently bad family relations. Socioeconomic status (typically including education, occupation, and income) affects allostatic load or overload in general populations [8]. In our study, we found that nonmedical workers had a higher prevalence of allostatic load than medical workers in unmatched samples and in PSM samples, adjusted for age, sex, and education. When we used PSM samples, adjusting for age, sex, education, employment, job change, and economic difficulties, there was no difference. Additionally, we found that those who were not employed had different reasons for unemployment. These findings indicated that the difference in the prevalence of allostatic load in both groups was caused by different socioeconomic conditions. Our results again emphasize that socioeconomic factors play an important role in allostatic load [8] and should be spotlighted in similar studies in the future.

The present results mirrored the reality of the society in China in the period since the lockdown of Wuhan on January 23, 2020 [23]. With great efforts made by the whole society, COVID-19 in China gradually has been controlled. Wuhan unlocked in an orderly way on April 8, 2020 [24]. In fact, as of the end of April, cases of COVID-19 have been cleared [25]. Despite the fact that there was another wave of COVID-19 emerging in Beijing, China had reduced coronavirus cases to nearly 0 by July 6, 2020 [26]. Society has been gradually reopened since the end of April [17], although these days some new confirmed cases have been reported in Xinjiang [27] and Dalian [28]. No certain treatment for COVID-19 currently exists [29]. Routine prevention measures for COVID-19, including masks, social distancing, eye protection, and hand and environmental disinfection [29, 30], are key to reducing the spread of COVID-19. Undoubtedly, city lockdowns due to COVID-19 are not a long-term solution for preventing COVID-19, and simultaneously preventing COVID-19 and returning to normal life is becoming the new state of normality in society [17, 31].

During the new stage of returning to a normal life, medical and nonmedical workers have been asked to gradually adapt to the new condition with routine preventions for controlling COVID-19, which is a stressor. Additionally, COVID-19, as a fatal stressor, has lasted many months and might have produced allostatic load or overload in those much exposed. Due to the different risks of being infected, citizens have gone through different feelings or pressure induced by COVID-19. However, with gaining more knowledge on how to prevent and control COVID-19 [32] and the sufficient supply of face masks [33], citizens have slowly become habituated to routine prevention of COVID-19 and have gained the ability to reduce the potential of being contracted [3]. In fact, by the early days of March 2020, with the updated guideline on COVID-19 [34], no doctors had been infected among about 40,000 medical personnel from the nation supporting Hubei medical services [35]. Therefore, in addition to COVID-19 as a source of stress, other pressures from daily life, especially those related to work and bad family relations, have started to become the most important source of distress. Specifically, job dissatisfaction and work conflicts were the main sources of stress for medical workers, and joblessness and bad family relations were the main sources of stress for nonmedical workers.

Social support and global well-being were independent protecting factors against allostatic load, while mental symptoms and abnormal illness behavior were risk factors. Our results indicated that social support could have a role in reducing the emergence of allostatic load in both groups; also psychological distress, hypochondriacal beliefs, and bodily preoccupations could worsen or exacerbate the occurrence of allostatic load in medical and nonmedical workers. The present findings parallel those on the role of social support in decreasing adverse consequences of stress [5]. Increasing social support and reducing clinical symptoms and abnormal illness behavior may be helpful to implement strategies that decrease or minimize allostatic load and overload. Indeed, allostatic overload could happen in a healthy population [36], the general population [7], and patients with various diseases [12, 37, 38].

The present study has some strengths. First, this is the first application of clinimetric criteria such as the PSI and the SQ in Chinese populations. Second, this is the first time the topic has been examined. Also, there are limitations. First, the psychological measurement was based on an online survey and self-report instruments. Clinical interviews and biological parameter collection are encouraged for future studies, which include endocrinological and physiological data and/or their variations in subjects with a bearing on allostasis before and after a social support intervention. Another limitation is that it was not possible to know the characteristics of those who did not take part in the survey (for instance their health condition or socioeconomic status), and thus we cannot confirm that the subjects of this study are representative of the general population.

In brief, medical workers had a similar prevalence of allostatic load than nonmedical workers during reopening of the society with strict routine prevention measures for COVID-19. The 2 groups felt various stresses with the progression of COVID-19. For medical workers, most stressors were related to job dissatisfaction and work conflict, while nonmedical workers' allostatic load was primarily related to joblessness and bad family relations. Different strategies should be provided to eliminate or minimize allostatic load in medical and nonmedical workers. Among them, social support might be a useful and practical one.

Statement of Ethics

All subjects gave their informed consent online. This study has been approved by the local ethics committee and is registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000039079).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have had no financial relationship with any organization that might have an interest in the submitted study in the last 3 years.

Funding Sources

H.W. was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC1310001 and 2016YFC1307000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771862), the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Project (Z171100000117016), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (KZ201710025017), the Beijing Municipal Hospital Research and Development Plan (PX2017069), and the Beijing Hundred, Thousand, and Ten Thousand Talents Project (2017-CXYF-09). The sponsors of this study had no role in the design, data management, or writing of this paper.

Author Contributions

M.P., L.W., Q.X., L.Y., B.Z., K.W., and H.W.: calculation of allostatic load according to the PSI. F.S. and H.W.: translation of the PSI and the SQ. M.P., L.W., Q.X., K.W., F.S., P.Z., Y.N., W.Z., W.Z., H.W., J.L., H.S., B.M., H.L., Y.J., H.C., Z.Y., Q.T., Y.Y., Z.Z., W.L., X.G., X.L., M.Y., P.W., P.W., C.W., J.L., L.J., X.H., D.L., D.X., Y.D., T.S., H.D., and Y.W.: conduction of this study. H.W. and L.Y.: statistical analysis. M.P., L.W., Q.X., and K.W.: administrative, technical, or material support. H.W.: drafting of this paper. F.C. and H.W.: critical revision of this paper. H.W.: conception, design, and supervision. All of the authors approved this paper.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgment

We thank all of the participants for their time and effort.

M.P., L.W., and Q.X. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.The Verge World Health Organization declares global public health emergency over coronavirus outbreak [Internet] [cited 2020 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.theverge.com/2020/1/30/21115357/coronavirusoutbreak-global-public-emergency-worldhealth-organization.

- 2.World Health Organization WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet] [cited 2020, Jul 23]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/

- 3.Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, Peng M, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89((4)):242–50. doi: 10.1159/000507639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao J, Wei J, Zhu H, Duan Y, Geng W, Hong X, et al. A study of basic needs and psychological wellbeing of medical workers in the fever clinic of a tertiary general hospital in Beijing during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89((4)):252–4. doi: 10.1159/000507453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theorell T. COVID-19 and working conditions in health care. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89((4)):193–4. doi: 10.1159/000507765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fava GA, McEwen BS, Guidi J, Gostoli S, Offidani E, Sonino N. Clinical characterization of allostatic overload. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019 Oct;108:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomba E, Offidani E. A clinimetric evaluation of allostatic overload in the general population. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81((6)):378–9. doi: 10.1159/000337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidi J, Lucente M, Sonino N, Fava GA. Allostatic load and its impact on health: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2020 Aug;•••:1–17. doi: 10.1159/000510696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard: China [Internet] [cited 2020 Jul 25]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/wpro/country/cn.

- 10.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar;382((13)):1199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide [Internet] [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortageof-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide.

- 12.Guidi J, Lucente M, Piolanti A, Roncuzzi R, Rafanelli C, Sonino N. Allostatic overload in patients with essential hypertension. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020 Mar;113:104545. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fava GA, Guidi J, Semprini F, Tomba E, Sonino N. Clinical assessment of allostatic load and clinimetric criteria. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79((5)):280–4. doi: 10.1159/000318294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fava GA, Cosci F, Sonino N. Current psychosomatic practice. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86((1)):13–30. doi: 10.1159/000448856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonino N, Fava GA. A simple instrument for assessing stress in clinical practice. Postgrad Med J. 1998 Jul;74((873)):408–10. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.74.873.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin J, Su Y, Lv X, Liu Q, Wang G, Wei J, et al. Perceived stressfulness mediates the effects of subjective social support and negative coping style on suicide risk in Chinese patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020 Mar;265:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.China Plus Headline News April 30, 2020, 10 PM [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: http://chinaplus.cri.cn/podcast/detail/2/52048.

- 18.CCTV News Client Central Steering Group: Over 3,000 medical staff in Hubei were infected in the early stage of the epidemic, currently no infection reports among medical aid staff [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 6]. Available from: https://politics.gmw.cn/2020-03/06/content_33626862.htm.

- 19.Piolanti A, Offidani E, Guidi J, Gostoli S, Fava GA, Sonino N. Use of the psychosocial index: a sensitive tool in research and practice. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85((6)):337–45. doi: 10.1159/000447760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benasi G, Fava GA, Rafanelli C. Kellner's symptom questionnaire, a highly sensitive patient-reported outcome measure: systematic review of clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89((2)):74–89. doi: 10.1159/000506110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao SY. Theoretical basis and application of the Social Support Rating Scale. J Clin Psychol Med. 1994;4((2)):98–100. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medical News Today COVID-19 global impact: How the coronavirus is affecting the world [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/covid-19-global-impact-howthe-coronavirus-is-affecting-the-world.

- 23.The Telegraph Virus-hit Chinese city goes into lockdown, with transport links severed and food shortage fears [Internet] [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/01/23/wuhan-lockdown-police-guard-train-stations-carsqueue-leave/

- 24.Chinanews Control of Wuhan Lihan and Hubei Channel officially lifted [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 8]. Available from: https://www.tellerreport.com/life/2020-04-08-control-of-wuhan-lihan-and-hubei-channel-officially-lifted-.H1xK9HqqvU.html.

- 25.Xinhua Wuhan's severe COVID-19 cases drop to zero: official [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 25]. Available from: http://www.china.org.cn/china/2020-04/25/content_75974686.htm.

- 26.Associated Press China reduces COVID-19 cases to near zero, now battling bubonic plague [Internet] [cited 2020, Jul 6]. Available from: https://fox8.com/news/coronavirus/china-reduces-covid-19-cases-to-nearzero-now-battling-bubonic-plague/

- 27.China Daily Xinjiang COVID-19 outbreak expected to slow: Public health expert [Internet] [cited 2020 Jul 20] Available from: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202007/20/WS-5f15a423a31083481725ad50.html.

- 28.Xinhua News Agency Update: China's Dalian reports two more confirmed COVID-19 cases [Internet] [cited 2020 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.msn.com/en-xl/news/other/update-chinas-dalian-reports-two-more-confirmed-covid-19-cases/ar-BB175DGC.

- 29.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020 Aug;324((8)):782–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schünemann HJ, et al. COVID-19 Systematic Urgent Review Group Effort (SURGE) study authors Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020 Jun;395((10242)):1973–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.General Office of the National Health Commission The National Health Commission further improves the ability of pre-hospital medical emergency response under the normalization of the prevention and control of COVID-19 epidemic [Internet] [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-07/14/content_5526762.htm.

- 32.National Health Commission of China Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. 8th ed (in Chinese) [Internet] [cited 2020 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202008/0a7bdf12bd4b46e5bd28ca7f9a7f5e5a/files/a449a3e2e2c94d9a856d5faea2ff0f94.pdf.

- 33.Sina Pharmaceutical News The supply of masks is sufficient and the price of melt blown cloth has plummeted [Internet] [cited 2020 Mar 22]. Available from: https://med.sina.com/article_detail_103_1_79482.html.

- 34.China News Network Two departments issue the novel coronavirus infection pneumonia diagnosis and treatment plan (trial version 7) [Internet] [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: http://www.chinanews.com/gn/2020/03-04/9113100.shtml.

- 35.Ma Xiaohua In January, Hubei had more than 3,000 medical infections, and the Wuhan Health and Medical Committee reported “None” for half a month [Internet] [cited 2020 Mar 6]. Available from: https://news.sina.com.cn/o/2020-03-06/doc-iimxyqvz8395569.shtml.

- 36.Offidani E, Ruini C. Psychobiological correlates of allostatic overload in a healthy population. Brain Behav Immun. 2012 Feb;26((2)):284–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Offidani E, Rafanelli C, Gostoli S, Marchetti G, Roncuzzi R. Allostatic overload in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2013 May;165((2)):375–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guidi J, Offidani E, Rafanelli C, Roncuzzi R, Sonino N, Fava GA. The assessment of allostatic overload in patients with congestive heart failure by clinimetric criteria. Stress Health. 2016 Feb;32((1)):63–9. doi: 10.1002/smi.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data