Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral pneumonia has been the most serious and lethal consequence of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) since the pandemic began in March of 2020. Currently there have been 8 million cases of COVID-19 in the United States and over 220,000 deaths (1). If we assume that at least 50% of patients with COVID-19 who died developed ARDS, then there has been a minimum of 100,000 deaths from COVID-19 ARDS in the United States within just 8 months. If we estimate mortality from COVID-19 ARDS to be 25%, then this estimate translates to at least 400,000 ARDS cases from COVID-19 to date and many more by the end of this calendar year. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were approximately 190,000 cases of classical ARDS annually in the United States (2). With this comparison, the annual incidence of COVID-19 ARDS probably exceeds the incidence of classical ARDS by at least twofold. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify mechanisms of lung and systemic injury in COVID-19, some of which can hopefully be translated to new effective therapies.

In this issue of the Journal, Hue and colleagues (pp. 1509–1519) report the results of a prospective observational study that compared patients with COVID-19 ARDS (n = 38) to patients who had classical ARDS (n = 36) (3). The patients with COVID-19 ARDS displayed a phenotype of impaired adaptive immune responses that was associated with severe lymphopenia (both CD4+ [cluster of differentiation 4–positive] and CD8+ T cells and B cells) and delayed lymphocyte activation. In addition, after adjustment for age and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, elevated concentrations of serum IP-10 (IFNγ-induced protein 10) and GM-CSF (granulocyte–macrophage colony–stimulating factor) were associated with increased mortality in patients with COVID-19 ARDS, findings that fit well with the role of IP-10 in recruiting T cells and monocytes and the contribution of GM-CSF in production of proinflammatory cytokines and leukocyte chemotaxis. In contrast, serum concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1Ra showed no differences between the COVID-19 ARDS versus classical ARDS and were not associated with mortality. Importantly, SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal loads were higher on admission and throughout the hospital course in patients who died. Coexpression of HLA-DR and CD38 on CD8+ T cells increased in the patients with COVID-19 over time, consistent with immune activation in the context of viral infection. Interestingly, serum concentration of EGF was elevated in the patients with COVID-19 ARDS compared with patients with classical ARDS, and was significantly higher in patients with COVID-19 ARDS who survived. These findings are summarized in Figure 1, emphasizing acute lung injury in the context of COVID-19.

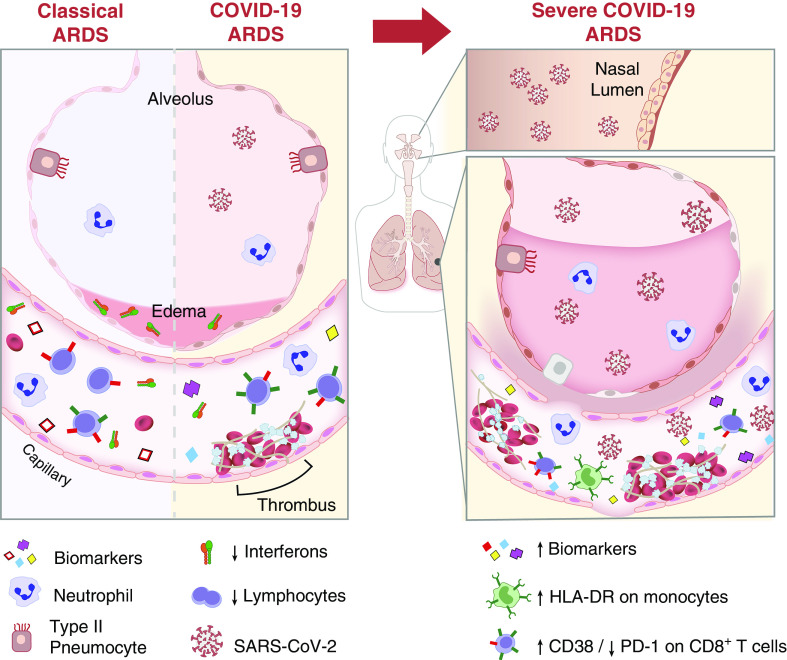

Figure 1.

Airway and alveolar biology during classical acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and coronavirus disease (COVID-19) ARDS. The alveolar–interstitial–capillary unit is similarly affected during classical ARDS and COVID-19 ARDS (left panel). In both types of ARDS, there is a marked upregulation of proinflammatory biomarkers, increase in capillary endothelial permeability, and an increase in inflammatory cells (neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages) in the vascular and alveolar compartments. There are, however, notable differences in the types of upregulated biomarkers, with lower expression of IFNs and an increase in thrombotic mediators in COVID-19 relative to classical ARDS. Relative to the milder forms of COVID-19 ARDS, significant alterations in severe COVID-19 ARDS (right panel) include a higher severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral load in both the upper airways (nasal lumen) and in the circulation, a higher neutrophil count and activity (i.e., NET formation), increase in inflammatory biomarkers and thrombosis, greater monocyte (HLA-DR expression) and lymphocyte activation (CD8+ T-cell CD38 expression), and more damage to the alveolar–interstitial–capillary unit.

There are strengths and shortcomings of this report. The comparison of patients with COVID-19 ARDS to classical ARDS made it possible to focus on COVID-19–specific factors in the pathogenesis of ARDS. However, because the study was restricted to a single center with a modest number of patients, the data do not provide insight into the spectrum of illness severity in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Nevertheless, what can we learn from this study regarding the biology of COVID-19 compared with classical ARDS, how do these results complement the findings in other COVID-19 studies, and how can we advance our understanding of mechanisms of injury in COVID-19 ARDS?

The association between increased mortality and higher nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in the study by Hue and colleagues matches well with new evidence of impaired type-1 IFN responses associated with more severe COVID-19 illness (4). Type-I IFNs inhibit viral replication and, as such, have direct antiviral effects (5). In a recent study by Hadjadj and colleagues (4), a cross-sectional analysis of 50 patients with COVID-19 identified a phenotype of markedly impaired IFN responses in patients with severe and critical COVID-19, specifically undetectable IFN-β and low INF-α production and activity in the serum, findings that were associated with a persistent viral load in the blood, a possible surrogate of uncontrolled lung infection (4). Patients with mild and moderate COVID-19 demonstrated robust IFN responses, as measured by gene expression in circulating leukocytes and serum IFN levels. This report also identified an exaggerated inflammatory response partly driven by the transcriptional factor NF-κB that might have been initiated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns, such as viral RNA. The mechanisms that explain the impaired IFN responses were not identified but could be mediated by SARS-CoV-2 itself (5), as occurred in other coronavirus-associated acute lung injury (6), genetic susceptibility, or other yet to be identified pathways.

What have we learned from other COVID-19 studies? Immunophenotyping of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes has demonstrated that the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, especially with a reduction in CD8+ T cells, is a marker of COVID-19 severity. Increased plasmablasts are also prognostic of organ failure (7). There is considerable heterogeneity in peripheral T-cell activation, ranging from robust to absent. We also know that vascular injury and thromboses of pulmonary capillaries, small and even larger vessels, are features of severe COVID-19 ARDS, more so than in influenza-induced ARDS or classical ARDS (8). There is also evidence that patients with severe COVID-19 ARDS have higher pulmonary dead space, decreased lung perfusion, and elevated circulating D-dimer (9). There are several candidate mechanisms to account for the lung and systemic vascular injury, including neutrophil extracellular traps (10) and hyperfibrinolysis that contribute to the elevated D-dimer (11).

What is needed now to further advance our understanding of the biologic mechanisms of injury in COVID-19 ARDS? Studies of protein biomarkers and gene expression in both the circulation and the airspaces would provide more insight into pathways of lung and systemic injury. Also, because dexamethasone in the RECOVERY (Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy) trial was especially effective in mechanically ventilated patients (12), biological marker measurements in different compartments before and after glucocorticoid treatment could help determine which pathways are altered, including quantification of type-I IFNs and SARS-CoV-2 viral load, because glucocorticoids can impair IFN-mediated viral clearance (13). Furthermore, we need to understand the mechanisms of recovery from COVID-19 ARDS. Elevated plasma EGF in the study by Hue and colleagues (3) was associated with better survival and may represent endogenous release of a factor that can stimulate alveolar epithelial cell regeneration and lung repair (14). More insights into regenerative pathways could be gained from studies with SARS-CoV-2 lung injury in mice (15). Significant progress has been made in understanding the pathogenesis of severe ARDS from COVID-19, although much more needs to be learned to account for the heterogeneity of disease severity, with a major focus on determining how much of the lung injury is due to direct viral invasion and how much from the resulting host immune response. There are therapeutic implications for both mechanisms. Thus far, there is one antiviral agent, Remdesivir, that has modest efficacy in mild to moderate disease (16) and one broad antiinflammatory agent, dexamethasone, with beneficial effects in severe disease (12), but more therapies are needed to mitigate pathogen- and host-mediated injury across the spectrum of COVID-19 illness severity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Diana Lim for her help with production of the figure.

Footnotes

Supported by HL140026 and HL123004 (M.A.M.), University of Toronto Clinician Investigator Program and the Clinician Scientist Training Program (A.L.), and by K24-DK113381 (K.D.L.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202009-3629ED on September 30, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. CDC COVID Data Tracker. [updated 2020 Oct 20; accessed 2020 Sep 23]. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker.

- 2. Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hue S, Beldi-Ferchiou A, Bendib I, Surenaud M, Fourati S, Frapard T, et al. Uncontrolled innate and impaired adaptive immune responses in patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1509–1519. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1885OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hadjadj J, Yatim N, Barnabei L, Corneau A, Boussier J, Smith N, et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science. 2020;369:718–724. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang BX, Fish EN. Global virus outbreaks: interferons as 1st responders. Semin Immunol. 2019;43:101300. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2019.101300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prompetchara E, Ketloy C, Palaga T. Immune responses in COVID-19 and potential vaccines: lessons learned from SARS and MERS epidemic. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2020;38:1–9. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kuri-Cervantes L, Pampena MB, Meng W, Rosenfeld AM, Ittner CAG, Weisman AR, et al. Comprehensive mapping of immune perturbations associated with severe COVID-19. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabd7114. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grasselli G, Tonetti T, Protti A, Langer T, Girardis M, Bellani G, et al. collaborators. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30370-2. [online ahead of print] 27 Aug 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Radermecker C, Detrembleur N, Guiot J, Cavalier E, Henket M, d’Emal C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps infiltrate the lung airway, interstitial, and vascular compartments in severe COVID-19. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20201012. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ji HL, Zhao R, Matalon S, Matthay MA. Elevated Plasmin(ogen) as a common risk factor for COVID-19 susceptibility. Physiol Rev. 2020;100:1065–1075. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, et al. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with covid-19 - preliminary report. N Engl J Med. [online ahead of print] 17 Jul 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cain DW, Cidlowski JA. Immune regulation by glucocorticoids. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:233–247. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matthay MA, Zemans RL, Zimmerman GA, Arabi YM, Beitler JR, Mercat A, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:18. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bao L, Deng W, Huang B, Gao H, Liu J, Ren L, et al. The pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in hACE2 transgenic mice. Nature. 2020;583:830–833. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, et al. ACTT-1 Study Group Members. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19 - preliminary report. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2022236. [online ahead of print] 22 May 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.