Abstract

On October 5th, 2020, Drs. Harvey J. Alter, Michael Houghton and Charles M. Rice were rewarded with Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for “the discovery of hepatitis C virus (HCV)”. During the past 50 years, remarkable achievements have been made in treatment of HCV infection: it has changed from being a life-threatening chronic disease to being curable. In this commentary, we briefly summarized the milestone events in the “scientific journey” from the first report of non-A, non-B hepatitis and discovery of the pathogen (HCV) to final identification of efficacious direct-acting antivirals. Further, we address the challenges and unmet issues in this field.

Background

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Drs. Harvey J. Alter, Michael Houghton and Charles M. Rice for the discovery of hepatitis C virus (HCV). HCV is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA hepatophilic virus. In contrast to oral transmission of hepatitis A virus (HAV) and bodily fluids-mediated transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV), HCV is primarily transmitted through blood transfusion and intravenous drug use. After acute HCV infection, approximately 75–85% of the patients develop chronic hepatitis C (CHC). Patients with CHC are prone to hepatic cirrhosis, chronic liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma [1]. HCV infects more than 170 million people worldwide, and approximately 10 million in China [1, 2], and thus represents a huge healthcare and economic burden.

Discovery of HCV

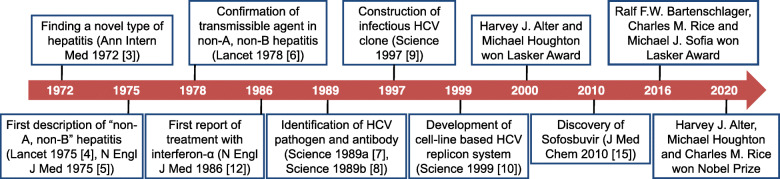

Discovery of HCV began with the finding a novel type of hepatitis in patients who received blood transfusion [3] (Fig. 1). HAV and HBV were not present in such patients [4, 5]. Alter and colleagues coined the term “non-A, non-B hepatitis” in 1975 [4]. They collected plasma/serum samples from a blood donor with chronic hepatitis and 4 people who developed “non-A, non-B hepatitis” after receiving blood transfusion, and injected these samples to 5 chimpanzees. As they suspected, all 5 chimpanzees developed hepatitis, as evidenced by elevated alanine aminotransferase as well as liver pathological changes, confirming the presence of a yet unknown transmissible agent in the blood of patients with non-A, non-B hepatitis [6].

Fig. 1.

Milestones in the discovery of HCV and development of treatment

In 1989, Houghton and colleagues constructed a random-primed complementary DNA library using plasma samples from patients with non-A, non-B hepatitis [7]. One clone in this library was not derived from host DNA, and appeared to be from a novel RNA virus belonging to the Flavivirus family (at least 10,000 nucleotides and is positive-stranded) [7]. Houghton and colleagues named this novel virus as HCV and reported a diagnostic assay using yeast-expressed recombinant polypeptide based on HCV genome to capture viral antibodies in the same journal that published the sequencing information [8].

Rice and colleagues later constructed a full-length clone of HCV complementary DNA that could transcribe an infectious RNA variant of HCV [9]. Upon intrahepatic inoculation of this clone, chimpanzees developed chronic hepatitis, with production of antibodies against HCV and viral replication in the blood [9]. Subsequently, Bartenschlager and colleagues developed an in vitro cell culture using a human hepatoma cell line to replicate HCV [10]. This cell-based model is indispensable in revealing the biological features of HCV as well as developing anti-HCV agents.

Identification and application of DAAs

Treatment of CHC with interferon-α, alone or in combination with ribavirin, is effective, but only in approximately 30% of the patients [11, 12]. Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications that directly block the activity of HCV non-structural proteins revolutionized the treatment of CHC [13]. PSI-6130 was the first DAA that inhibits the HCV NS5B RNA polymerase and selectively suppresses HCV replication [14], but clinical development effort was abandoned due to low bioavailability. PSI-7851, also known as sofosbuvir, is a PSI-6130 derivative [15], and improved in vivo efficacy against HCV of various genotypes [16, 17]. Ledipasvir is a DAA that inhibits the HCV NS5A RNA polymerase [18, 19]. The combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir achieved >95% response rate with minimal side effects in adult CHC patients [13]. The latest development is Vosevi. As a polypill (sofosbuvir, velpatasvir and voxilaprevir in a single tablet), Vosevi is easy to use, and has many advantages, including improved pharmacokinetics and strong antiviral activity. There has been speculation that with Vosevi and other treatments in the pipeline, we are now approaching the ultimate WHO goal of eradicating HCV by 2030.

Conclusion and perspective

Despite of the optimism brought about by the advances in the past decades, many challenges are ahead [20]. First, there is no effective vaccine in sight. Also, cured patients often fail to gain fully reinvigorated immunity. Second, more efforts must be made to identify and treat asymptomatic patients. Third, high risk behaviors (such as needle sharing) must be curbed. Last but not least, effective treatments must be made accessible to all infected people.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CHC

Chronic hepatitis C

- HAV

Hepatitis A virus

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

Authors’ contributions

FSW conceived and designed this paper. WH wrote the manuscript. CZ and JJS revised the manuscript. JYZ contributed to the literature research. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Webster DP, Klenerman P, Dusheiko GM. Hepatitis C. Lancet. 2015;385:1124–1135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62401-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang FS, Fan JG, Zhang Z, Gao B, Wang HY. The global burden of liver disease: the major impact of China. Hepatology. 2014;60:2099–2108. doi: 10.1002/hep.27406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alter HJ, Holland PV, Purcell RH, Lander JJ, Feinstone SM, Morrow AG, et al. Posttransfusion hepatitis after exclusion of commercial and hepatitis-B antigen-positive donors. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:691–699. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-5-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alter HJ, Holland PV, Morrow AG, Purcell RH, Feinstone SM, Moritsugu Y. Clinical and serological analysis of transfusion-associated hepatitis. Lancet. 1975;2:838–841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feinstone SM, Kapikian AZ, Purcell RH, Alter HJ, Holland PV. Transfusion-associated hepatitis not due to viral hepatitis type a or B. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:767–770. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197504102921502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alter HJ, Purcell RH, Holland PV, Popper H. Transmissible agent in non-a, non-B hepatitis. Lancet. 1978;1:459–463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-a, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuo G, Choo QL, Alter HJ, Gitnick GL, Redeker AG, Purcell RH, et al. An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-a, non-B hepatitis. Science. 1989;244:362–364. doi: 10.1126/science.2496467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolykhalov AA, Agapov EV, Blight KJ, Mihalik K, Feinstone SM, Rice CM. Transmission of hepatitis C by intrahepatic inoculation with transcribed RNA. Science. 1997;277:570–574. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohmann V, Korner F, Koch J, Herian U, Theilmann L, Bartenschlager R. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science. 1999;285:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoofnagle JH, Seeff LB. Peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2444–2451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct061675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoofnagle JH, Mullen KD, Jones DB, Rustgi V, Di Bisceglie A, Peters M, et al. Treatment of chronic non-A,non-B hepatitis with recombinant human alpha interferon. A preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1575–1578. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612183152503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, Hyland RH, Ding X, Mo H, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:515–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark JL, Hollecker L, Mason JC, Stuyver LJ, Tharnish PM, Lostia S, et al. Design, synthesis, and antiviral activity of 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methylcytidine, a potent inhibitor of hepatitis C virus replication. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5504–5508. doi: 10.1021/jm0502788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sofia MJ, Bao D, Chang W, Du J, Nagarathnam D, Rachakonda S, et al. Discovery of a beta-d-2′-deoxy-2′-alpha-fluoro-2′-beta-C-methyluridine nucleotide prodrug (PSI-7977) for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7202–7218. doi: 10.1021/jm100863x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, Yoshida EM, Rodriguez-Torres M, Sulkowski MS, et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1867–1877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1878–1887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao M, Nettles RE, Belema M, Snyder LB, Nguyen VN, Fridell RA, et al. Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect. Nature. 2010;465:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature08960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawitz EJ, Gruener D, Hill JM, Marbury T, Moorehead L, Mathias A, et al. A phase 1, randomized, placebo-controlled, 3-day, dose-ranging study of GS-5885, an NS5A inhibitor, in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2012;57:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartenschlager R, Baumert TF, Bukh J, Houghton M, Lemon SM, Lindenbach BD, et al. Critical challenges and emerging opportunities in hepatitis C virus research in an era of potent antiviral therapy: considerations for scientists and funding agencies. Virus Res. 2018;248:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.