Pediatricians often serve as interpreters and mediators of health guidelines when discussing vaccines, health screening, and lifestyle choices with parents of our patients. Outside of public health emergencies, these discussions nearly exclusively focus on optimizing the health of the individual child and a focus on family preferences. However, in the current pandemic, nearly everyone has experienced limitations of personal activities for the population health goal of curbing the spread of the novel coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). New information continues to become available about infrequent but serious COVID-19 complications in children, including neurologic and inflammatory sequalae from illness, as well as the role children play in the spread of the virus.1, 2, 3 Moreover, children of color experience a greater proportion of severe COVID-19-related disease, including higher rates of hospitalization and death.4 We also know that the measures helping to control COVID-19 infection rates have negatively impacted the health of children through delays in routine vaccination and well-child care, the mental health consequences of school closures, and heightened concerns about the risk of child abuse in socially isolated children.5, 6, 7 These unintended consequences are presumed to be acceptable harms to protect the public health.

As children return to medical care and some return to in-person schooling, pediatricians are now tasked with navigating concepts in public health ethics when helping parents make decisions affecting their children and the larger community. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has released guidance on face coverings, testing protocols, and the use of personal protective equipment in the context of communities and schools trying to reopen even as rates of new COVID-19 infections increase.8 Nonetheless, questions for pediatricians remain problematic. How can pediatricians balance the needs of their patients with those of the population at large during the COVID-19 public health crisis? How should pediatricians respond when parents’ preferences do not align with public health strategies? What adjustments must be made to the typical model of pediatric shared decision-making (SDM) when guiding parents through clinical decisions that benefit the population as a whole, but lead to limiting choices of the individual patient?

In this commentary, we examine how values typically prioritized in public health ethics such as solidarity and justice can be integrated into SDM, where the individual child's best interest and caregiver preferences are often paramount. Additionally, we suggest a framework to integrate public health ethics into the traditional SDM continuum using 4 scenarios that we examine for risks, benefits, settings, and appropriate levels of directiveness. Although maintaining an awareness of the evolving epidemiology of COVID-19, and in particular, its impact on vulnerable groups, pediatricians must have a solid working knowledge of public health ethics and law to allow them to navigate these conversations effectively.

Approaches to Guide Pediatricians Counseling Families

SDM

When multiple ethically reasonable approaches to care exist, parents or legal guardians (caregivers) and pediatricians typically engage in SDM, grounded in principles of caregiver authority (respect for autonomy) and the child's best interests (beneficence).9 Both parties bring knowledge, values, and preferences to the discussion and work collaboratively, negotiating the contributions of each party to the decision making process and facilitating information exchange to decide what is best for the child, within the context of family goals. The process is highly value sensitive and, importantly, relies on the provider encouraging a bidirectional exchange of information to elicit patient and caregiver preferences.10 SDM generally defers the decision to caregiver views of what is “best” provided they are reasonable and do not lead to harm for the child.11

Public Health Ethics

In public health emergencies, the principles of beneficence (maximizing benefit), and nonmaleficence (avoiding harm) that commonly guide individual decisions in health care are viewed instead through the lens of impact at the population level. Values of justice (the fair distribution of societal burdens and benefits) and solidarity increase in importance. Solidarity is characterized as affirming the moral standing of others and their membership in a community of equal dignity and respect. As Jennings summarizes, solidarity emphasizes an “attention to the moral (and mortal) being of others and their needs, suffering, and vulnerability.”12 Solidarity can also be understood as a call to stand with or assist community members for overall community good and a method to combat structural and systemic injustices.13

Applying these values may at times conflict with principles guiding individual health decisions, such as autonomy.14 The state's police powers to safeguard its people permit paternalistic restrictions on individual liberties when the population-level benefits of the interventions outweigh the harms of individual restrictions. Protection is sometimes achieved through restrictions to individual liberties to actively prevent 1 person from making choices that increase the risk of harm to others. When public health authorities legally mandate a public health practice, the intervention must prevent an avoidable harm, have a “real or substantial relation” to protecting public health, ensure that burdens are not disproportionate to expected benefits, and not pose undue risks.15 Interventions are also justified under frameworks of public health ethics when the intervention is effective, offers significant public health benefit, confers minimal individual burden and risk, and distributes burdens and benefits fairly.16 When such conditions are met, pediatricians (within their practices) and public health officials may have more authority to impose such interventions. However, these interventions may run counter to caregiver preferences under traditional SDM.

The Integration of Public Health Goals with Traditional Shared Decision Making

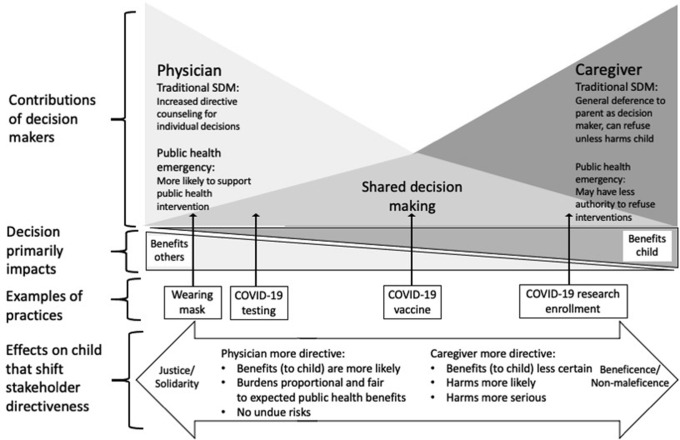

As described elsewhere in the Commentary, the traditional SDM framework is guided by caregiver and patient goals and values. The public health framework requires serious attention to population-level goals and, therefore, heavily relies on the consideration of risks or burdens and benefits at the population level, even if these measures require subsuming some individual interests to meet the goals of justice and solidarity. Pediatricians accustomed to the traditional SDM framework need to navigate these discussions of risk, burden, and benefit at both the individual and population levels when guiding parents through individual health decisions and considerations of various public health interventions. Contributions to SDM may shift from the traditional model, as demonstrated in the Figure . Under traditional SDM, pediatricians defer to caregiver choices, offering more directive recommendations as interventions present children lower risks and higher benefits. Contributions to decision making will be most equally distributed between physician and caregiver when neither benefits nor risks to the child predominate, with differential ratios of risks and benefits shifting contributions to decision making more toward physician or caregiver. Public health decision making prioritizes solidarity, justice, and law, resulting in more physician directiveness when interventions present high population benefits, fairly distributed burdens proportionate to benefits, and low risks or harms to child. To this end, pediatricians will need become facile in discussing justice considerations with families and older children and explain how following public health guidelines benefits communities as a whole and those that might be at greater risk.

Figure.

How does integrating public health considerations relevant to COVID-19 impact shared decision making for children? Under all circumstances, there is a range of shared decision making based on the question, the stakeholders' goals and values. In traditional SDM counseling by pediatricians becomes more directive as interventions present children lower risks and higher benefits. In contrast, public health decision making prioritizes solidarity, justice and law, resulting in more physician directiveness when interventions present population benefits, fairly distributed burdens proportionate to benefits, and low risks/harms to child.

Reconciling Public Health Goals and Traditional Shared Decision Making

We discuss 4 applications of the combined SDM and public health frameworks relevant to COVID-19. These examples, although not exhaustive, were chosen to illustrate varying risk-benefit profiles to the individual and population. Under this framework, information exchange that occurs in SDM will need to include a discussion of the risks and benefits to public health when appropriate. Contributions to SDM will differ depending on the population-level benefits of particular interventions and the risks and benefits to the child. Such conversations should nonetheless incorporate patient and caregiver preferences to the greatest extent possible, respecting traditional principles of SDM.

Masking

Because people may be asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19, masks are recommended to prevent transmission when social distancing is not possible, except in very young children or those with medical conditions precluding their use.17 However, there is no national masking policy and recommendations remain variable across different regions.18 Pediatricians may encounter decisions about mask wearing both within the context of policies and practices within their own clinical environment and in helping families navigate the potential need for mask wearing in other settings. Public health ethics principles described above would support pediatricians who mandate mask wearing in clinical settings given the minimal burden to wearers and collective benefits for other patients and staff.

Masking can be thought of as a universal precaution similar to immunizations; both are intended to afford the individual protection, but also to diminish disease transmission to others. Similar to the case of vaccinations, pediatricians may be asked by some caregivers to allow exceptions to rules for mask wearing. Permissible exceptions will require strong medical justification, such as medical conditions in which the mask would make breathing difficult or if an individual lacks the capacity to remove the mask, such as children younger than 2 years of age or those with severe neurodevelopmental impairments. One might also consider allowing exceptions for a child with strong behavioral challenges that practically make wearing a mask very difficult—if the struggle to continue the mask wearing could actually increase transmission of viral particles, clearly the benefit of the mask would be lost. In such circumstances, alternatives to masks such as face shields or alternatives to visits in the clinical setting, such as a telehealth appointment, should be considered when feasible. Negotiating such conversations requires balancing the public health benefits of mask wearing with the potential individual risks and benefits associated with the practice. Only when there are compelling risks to the patient or loss of benefit to the public would it be ethically acceptable for pediatricians to accommodate requests to exempt patients from mask wearing requirements or to recommend against mask wearing generally.17

Community rates of disease and acceptance of masking varies across regions and at different points in time. Compliance becomes more critical as rates of infection increase. Exceptions to masking, therefore, may vary in impact based on the local disease burden at the time in question. However, the best practice remains to counsel universal masking, regardless of rates of COVID-19, so that when exceptions are necessary, those surrounding the child are in compliance and making the situation as safe as possible. Conversely, pediatricians may need to support patients seeking to protect themselves and others but who are struggling with family or community members who do not comply with public health recommendations. Pediatricians can equip families with evidence, information, and tools to help facilitate conversations with family members or community members (eg, how to get a child to become comfortable with mask wearing, why masking protects others, airborne transmission in indoor gathering vs outdoor gatherings, etc).19

Targeted COVID-19 Testing of Asymptomatic Children

Many hospitals require COVID-19 testing of asymptomatic children before certain invasive procedures and hospital admissions. Although some patients may individually benefit from knowing test results, the primary benefit of testing is not to the individual, but to facilitate appropriate levels of infection control, including proper room assignment, judicious use of personal protective equipment, and optimizing hospital operations.20 Some parents may prefer to forego testing to avoid the perceived burden of discomfort to the child. Although this is a small but real burden to the child, the benefits of protecting health care resources and other patients make mandating COVID-19 testing ethically permissible. However, accommodations may need to be considered as burdens and risks to patient increase (eg, for children who may have such significant aversions that they would require sedation to tolerate testing).

As testing methods become less invasive, more rapid and reliable, and available in greater volumes, risks and benefits will continue to evolve. The AAP has recently advocated for continued asymptomatic testing after contact exposure because of the high rates of many (but not all) asymptomatic children.21 Mandating repeated testing protocols such as those proposed to allow for safer activities (eg, testing every few days of on-campus college students) should improve the calculus of the benefits over risks, although even despite such a program, for example, at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, surges have forced temporary in-person instruction closures.22

COVID-19 Vaccination

When a vaccine is available, supplies will likely be limited, requiring consideration of whom should be prioritized for vaccination. Children will be an important population to vaccinate, given potential for spreading through asymptomatic carrier children, particularly as schools and daycares reopen. Pediatricians will need to engage families in SDM and directive counseling to the weigh benefits of viral protection for the child and others against possible unknown risks. There also exists a need from professional societies and the public health infrastructure to provide clear guidance and messaging on the importance of vaccination specifically in the context of COVID-19.23 Returning children to school safely is important for academics and the healthy development and well-being of children, and although this goal remains elusive for many reasons, mass vaccination of children may need to be an important consideration.24 Nevertheless, mandating vaccination soon after release would be fraught with challenges given the accelerated vaccine development timeline, potential unknown risks and complications, and evolving understanding of COVID-19 epidemiology.25 , 26 The US Food and Drug Administration's options for approving a new vaccine (whether a vaccine works) will depend on its efficacy, its proportional uptake, and the rates of the virus in that community. Whether a vaccine is safe will be gauged by risks and degrees of harm agreed upon as acceptable.27 Despite the anticipated public health benefits of achieving herd immunity and the possibility of returning to school faster, prematurely mandating COVID-19 vaccination could also aggravate hesitancy and refusals pediatricians already face with vaccines.28 These considerations are likely to be more salient in communities of color, who have already suffered a disproportionate burden of disease. For COVID-19, involvement in vaccine trials has also been lower for Black participants, which may also contribute to increasing vaccine hesitancy in the future.29 Therefore, parents should be allowed to refuse any potential COVID-19 vaccine until the risks and efficacy are well-established in children.

When a COVID-19 vaccine is deemed to be safe and available for distribution to children, pediatricians will be asked to help interpret for families the guidance from federal agencies and professional societies such as the AAP to make thoughtful decisions for their children. Pediatricians who have already established trusting relationships with their patients will be the best ambassadors for vaccine-related questions. Families who display vaccine hesitancy for existing immunizations will benefit from pediatricians who strengthen families’ health literacy and who use proven methods to ensure understanding of information, including information technology.30, 31, 32

Research

Therapeutics for COVID-19 remain under investigation, and some children suffer serious postinfectious complications.2 Pediatricians should anticipate counseling families about current knowledge on alternative treatments and assist them in understanding the risks and benefits of enrolling infected children in pediatric studies. Participation of children in COVID-19 research studies remains important so that children have appropriate and early access to future medical treatments and support for psychological sequelae; such sequelae have been reported during and after natural disasters. For observational studies (eg, tracking outcomes for children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children) that pose minimal risk to the child, pediatricians may be more directive in recommending participation while being mindful that children may have special vulnerabilities after a traumatic event like this pandemic.33 In contrast, investigational treatments with higher potential harms but possible benefits such as an unproven medication to prevent multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in a child infected with COVID-19 or a vaccine trial will likely pose greater risks to the child and require careful exploration by pediatrician and caregiver with more deference to caregiver preferences.

Specifically, the AAP has advocated for the inclusion of children in research on potential COVID-19 vaccine and said:

[I]t is counter to the ethical principle of distributive justice to allow children to take on great burdens during this pandemic but not have the opportunity to benefit from a vaccine, or to delay that benefit for an extended period of time, because they have not been included in vaccine trials. Children must be included in vaccine trials to best understand any potential unique immune responses and/or unique safety concerns.34

Recently, children older than age 12 years are eligible to participate in COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials.35 Families considering participating will need to weigh risk to their child as well as the potential public health benefit; pediatricians can support caregivers’ decision making by helping the family to understand the potential overall benefit to the adolescent and ensure there is assent from the adolescent. Ultimately, deference should be given to caregiver choices.

Special Considerations for Adolescents

Adolescents have developing autonomy and some may have decision making capacity similar to that of an adult and should participate in SDM as it pertains to their own health care. When adolescent values differ from that of their family and impact health care choices, pediatricians need to share information, practice good communication, ensure transparency, and sometimes engage in conflict resolution. If there is a disagreement related to COVID-19 where a family endorses masking, social distancing, and testing, but the adolescent does not, the pediatrician may need to explore personal and community barriers and provide best practice guidance through evidence-based current public health recommendations. Although state laws differ in adolescents' ability to give sole consent for immunizations, the pediatrician can strive to help parents and the patient arrive at a shared decision by providing a space for clarifying concerns, medical facts, and goals in a way that respects both stakeholders. Finally, the pediatrician may need to help support decision making that allows the adolescent to feel safe, such as if the patient attends school in a region where there is no masking requirement. In each scenario, the pediatrician will need to assess the adolescent's level of evolving decision-making capacity to help titrate information delivery, the deliberation over risks and benefits, and the degree of adolescent participation in decision making.

Special Considerations for Groups at Risk for Experiencing Disproportionate Burdens from COVID-19 Illness and Public Health Measures in Response to the Pandemic

Minority groups have experienced higher rates of illness and mortality from COVID-19. Higher rates of infection and mortality are due, in large part, to systemic biases and structural inequities that create baseline disparate health care access, quality, and outcomes for certain groups of people.36 Of the nearly 800 reported cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, 70% occurred in Black and Hispanic/Latino children.37 The very same groups that would most likely benefit from an effective vaccine or study of this disease have also shown greater rates of mistrust in the health system and in research attributable to historical experiences of unethical treatment.38 Given this delicate juxtaposition of need and trust, public health efforts that aim to address health equity have the best chances of restoring faith in general medical care.

This dynamic generates additional considerations and challenges for pediatricians who counsel minority families in situations where public health goals may differ from individual preferences. Pediatricians need to use models that bridge the gaps between health care professionals and the families they serve, especially in the face of different cultural experiences.39 Preserving and respecting SDM requires that pediatricians engage in thoughtful and informed dialogue with special attention to reflective listening, incorporation of health-literate sensitive educational materials, acknowledgement of explicit and implicit biases, awareness and validation of current and past mistreatment, and with attention to the potential for institutional inequities to build trust and to avoid perpetuating existing disparities.40 Any consideration of mandatory interventions in particular should include specific attention to measuring the impact on groups at risk for disparities and gauging whether changes in structural and systemic practices may have unintended consequences that worsen existing disparities and mistrust.41 It is important to note that, in addition to considerations for their interpersonal interactions with caregivers and families, to further principles of public health ethics, pediatricians also have a special role in addressing these structural and systemic issues as advocates for children. It is especially important that existing disparities are not worsened when negotiating public health goals and SDM.

Conclusion

Interventions offering high chances of benefit to the population and low risks to individuals may be ethically mandated by pediatricians and legally mandated by public health officials under ethical and legal public health frameworks. As risks to the individual patient increase in likelihood or in degree of harmfulness, a more traditional SDM model emphasizing individual goals may be most appropriate. By integrating public health law and ethics into traditional models of SDM, pediatricians can guide families through decisions affecting public health and their children.

Individual health care decisions related to COVID-19 that impact public health goals may require more directive counseling and education by pediatricians when the benefits to the public are widespread and certain and harms to individual children are minimal and unlikely. Reconciling public health goals and SDM frameworks may sometimes require balancing competing values, preferences, and medical considerations. Pediatricians have a special responsibility to guide and educate caregivers in navigating these situations, which includes balancing individual preferences and public health goals, encouraging information sharing, and ultimately preserving the caregiver role in SDM. Additionally, pediatricians have an important role in addressing unique considerations for children facing disproportionate burdens in the current pandemic. To effectively navigate these responsibilities, pediatricians must have an understanding of individual SDM and public health ethics and law and in which situations one framework might take precedence over the other.

Acknowledgments

We thank Craig Klugman, PhD, for his review of this report.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Abdel-Mannan O., Eyre M., Löbel U., Bamford A., Eltze C., Hameed B., et al. Neurologic and radiographic findings associated with COVID-19 infection in children. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldstein L.R., Rose E.B., Horwitz S.M., Collins J.P., Newhams M.M., Son M.F., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wald E.R., Schmit K.M., Gusland D.Y. A pediatric infectious disease perspective on COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1095. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabin R.C. Why the Coronavirus more often strikes children of color. www.nytimes.com/2020/09/01/health/coronavirus-children-minorities.html

- 5.United Nations Sustainable Development Group The impact of COVID-19 on children. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-impact-covid-19-children

- 6.Feltman D.M., Moore G.P., Beck A.F., Sifferman E., Bellieni C., Lantos J. Seeking normalcy as the curve flattens: ethical considerations for pediatricians managing collateral damage of COVID-19. J Pediatr. 2020;225:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenthal C.M., Thompson L.A. Child Abuse Awareness Month during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:812. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics Cloth face coverings. https://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/cloth-face-coverings/

- 9.Kon A.A. The shared decision-making continuum. JAMA. 2010;304:903–904. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Global Seminar Salzburg. Salzburg statement on shared decision making. BMJ. 2011;342:d1745. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz A.L., Webb S.A., American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161485. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jennings B. Relational ethics for public health: interpreting solidarity and care. Health Care Anal. 2019;27:4–12. doi: 10.1007/s10728-018-0363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould C. Solidarity and the problem of structural injustice in healthcare. Bioethics. 2018;32:541–552. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gostin L.O., Jacobson V. Massachusetts at 100 years: police power and civil liberties in tension. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:576–581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harlan, John Marshall, Supreme Court of the United States U.S. Reports: Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11. 1904. www.loc.gov/item/usrep197011/

- 16.Kass N.E. An ethics framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1776–1782. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu D.K., Akl E.A., Duda S., Solo K., Yaacoub S., Schunemann H.J. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395:1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller H. Coronavirus mask mandates differ across the country as hot spots multiply and states play politics. www.cnbc.com/2020/06/26/coronavirus-mask-mandates-differ-across-the-country-as-hot-spots-multiply.html

- 19.American Academy of Pediatrics COVID 19. www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/COVID-19/Pages/default.aspx

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidance for healthcare professionals who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html

- 21.Goza S. AAP statement on CDC recommendations against COVID-19 testing for asymptomatic individuals. https://services.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2020/aap-statement-on-cdc-recommendation-against-covid-19-testing-for-asymptomatic-individuals/

- 22.Nadworny E. Despite mass testing, University of Illinois sees coronavirus cases rise. NPR. www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/09/03/909137658/university-with-model-testing-regime-doubles-down-on-discipline-amid-case-spike

- 23.Mello M.M., Silverman R.D., Omer S.B. Ensuring uptake of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1296–1299. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2020926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Academy of Pediatrics COVID-19 planning considerations: guidance for school re-entry. https://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/covid-19-planning-considerations-return-to-in-person-education-in-schools/

- 25.O’Callaghan K.P., Blatz A.M., Offit P.A. Developing a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine at warp speed. JAMA. 2020;324:437–438. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lurie N., Sharfstein J.M., Goodman J.L. The development of COVID-19 vaccines: safeguards needed. JAMA. 2020;324:439–440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah A., Marks P.W., Hahn S.M. Unwavering regulatory safeguards for COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA. 2020;324:931–932. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gidengil C., Chen C., Parker A.M., Nowak S., Matthews L. Beliefs around childhood vaccines in the United States: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2019;37:6793–6802. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farmer B. As Covid-19 vaccine trials move at warp speed, recruiting black volunteers takes time. www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/09/11/911885577/as-covid-19-vaccine-trials-move-at-warp-speed-recruiting-black-volunteers-takes

- 30.Marti M., de Cola M., MacDonald N.E., Dumolard L., Duclos P. Assessments of global drivers of vaccine hesitancy in 2014-Looking beyond safety concerns. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gianfredi V., Moretti M., Lopalco P.L. Countering vaccine hesitancy through immunization information systems, a narrative review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:2508–2526. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1599675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodman J.L., Grabenstein J.D., Braun M.M. Answering key questions about COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20590. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferreira R.J., Buttell F., Cannon C. Ethical issues in conducting research with children and families affected by disasters. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:42. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0902-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Academy of Pediatrics Letter to HHS and FDA-Children in COVID 19 Vaccine Trials. https://downloads.aap.org/DOFA/AAPLettertoHHSandFDAChildreninCOVID19VaccineTrials.pdf

- 35.Aubrey A. Will kids get a COVID-19 vaccine? Pfizer to expand trial to ages 12 and up. www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/10/13/923248377/will-kids-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-pfizer-to-expand-trial-to-ages-12-and-up

- 36.Abedi V., Olulana O., Avula V., Chaudhary D., Khan A., Shahjouei S., et al. Racial, economic and health inequality and COVID-19 infection in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00833-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Center for Disease Control and Prevention Health department-reported cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) in the United States. www.cdc.gov/mis-c/cases/ind37,ex.html

- 38.Sullivan L.S. Trust, risk, and race in American medicine. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020;50:18–26. doi: 10.1002/hast.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellis W.R., Dietz W.H. A new framework for addressing adverse childhood and community experiences: the building community resilience model. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:S86–S93. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Derrington S.F., Paquette E., Johnson K.A. Cross-cultural interactions and shared decision-making. Pediatrics. 2018;142:S187–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0516J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trent M., Dooley D.G. Dougé J, Section on Adolescent Health, Council on Community Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence. The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20191765. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]