Abstract

Mouse spermatogenesis is supported by spermatogenic stem cells (SSCs). SSCs maintain their pool while migrating over an open (or facultative) niche microenvironment of testicular seminiferous tubules, where ligands that support self-renewal are likely distributed widely. This contrasts with the classic picture of closed (or definitive) niches in which stem cells are gathered and the ligands are highly localized. Some of the key properties observed in the dynamics of SSCs in the testicular niche in vivo, which show the flexible and stochastic (probabilistic) fate behaviors, are found to be generic for a wide range of, if not all, tissue stem cells. SSCs also show properties characteristic of an open niche-supported system, such as high motility. Motivated by the properties of SSCs, in this review, I will reconsider the potential unity and diversity of tissue stem cell systems, with an emphasis on the varying degrees of ligand distribution and stem cell motility.

OVERVIEW OF MOUSE SPERMATOGENESIS

Mouse spermatogenesis is supported by the robust and active functions of spermatogenic (spermatogonial) stem cells (SSCs). Spermatogenesis takes place in the seminiferous tubules (precisely, convoluted seminiferous tubules) packed within the testicular capsule (Fig. 1A; Russell et al. 1990; Yoshida 2019). Seminiferous tubules have a simple tube-like architecture with a diameter of 150–200 µm. A single mouse testis has ∼1.7-m-long seminiferous tubules comprised of ∼10 separate loops (Fig. 1A). Throughout their length and circumference, seminiferous tubules present a uniform tissue organization (Fig. 1B,C). Their structural framework is primarily based on highly specialized somatic cells called Sertoli cells, which consist of an epithelium with a prominent basement membrane and tight junction. The epithelial sheet of Sertoli cells nourishes all the stages of spermatogenic cells, together forming a composite “seminiferous epithelium.” Spermatogonia, the mitotic germ cells including SSCs, are located within the “basal compartment,” the gap between the junctional complex and basement membrane (Russell et al. 1990; Meistrich and van Beek 1993; Yoshida 2018a). At the beginning of meiosis, these cells translocate across the junction to the adluminal compartment and undergo meiotic divisions to form haploid spermatids, which then mature into spermatozoa that are eventually released into the lumen. The entire process of spermatogenesis takes approximately 35 days and 60 days in mice and humans, respectively. Such simple and homogeneous cell arrangements and tissue configurations provide an invaluable opportunity for investigating stem cell behavior in the basal compartment, in a reproducible manner suitable for quantitative and statistical analyses.

Figure 1.

Tissue organization of mouse testes and seminiferous tubules. (A) Macroscopic view of a mouse testis. In the testicular capsule (tunica albuginea), long convoluted seminiferous tubules with a total length of ∼1.7 m per testes are tightly packed as ∼10 separate loops connecting to rete testes, the common outlet of sperm. Only a single loop is shown. (B) A pair of seminiferous tubules (rectangle in A), with a vasculature network of arterioles and venules (red) and surrounding interstitial cells (including testosterone-producing Leydig cells and macrophages; yellow), which together comprise the interstitium between the tubules. (C) Tissue architecture of a part of seminiferous epithelium (rectangle in B). Within the anatomical framework composed of somatic cell types (e.g., Sertoli cells, peritubular myoid, and lymphatic endothelial cells), which separate adluminal and basal compartments, all the stages of germ cells show a stratified organization. The spermatogonia (mitotic cells) are located in the basal compartment, whereas meiotic spermatocytes and haploid round and elongating spermatids are in the adluminal compartment. (B and C from Yoshida 2019; modified, with permission, from the author.)

SSCs comprise a small fraction of spermatogonia and are located within the basal compartment. In addition to Sertoli cells and the basement membrane, an ensemble of other somatic cells including peritubular myoid cells, lymphatic endothelial cells, interstitial cells, and vasculature, as well as differentiating germ cells, are implicated in the regulation of SSCs in the basal compartment (Fig. 1C; for review, see Yoshida 2018a).

SSC IDENTITY AND REGULATION

SSC activity resides within a minor fraction of spermatogonia called “undifferentiated spermatogonia” (Aundiff), which show heterogeneous topology (Fig. 2A; Russell et al. 1990; Meistrich and van Beek 1993; de Rooij and Russell 2000; Phillips et al. 2010; de Rooij 2017; Yoshida 2019). Unique to germ cells, although some fractions of Aundiff are singly isolated (called Asingle or As), many others are interconnected with each other via intercellular bridges (ICBs), forming variable lengths of syncytia including Apaired (Apr) and Aaligned (Aal) (Russell et al. 1990). A majority of Aal are composed of 2n cells (i.e., 4, 8, 16, etc.) as a result of the incomplete cytokinesis in the telophase of mitotic divisions, which connected the mitotic sisters, and the synchronous cell-cycle progression among interconnected cells (Russell et al. 1990), although some compose “odd” numbers of cells other than 2n because of fragmentation of syncytia (described below).

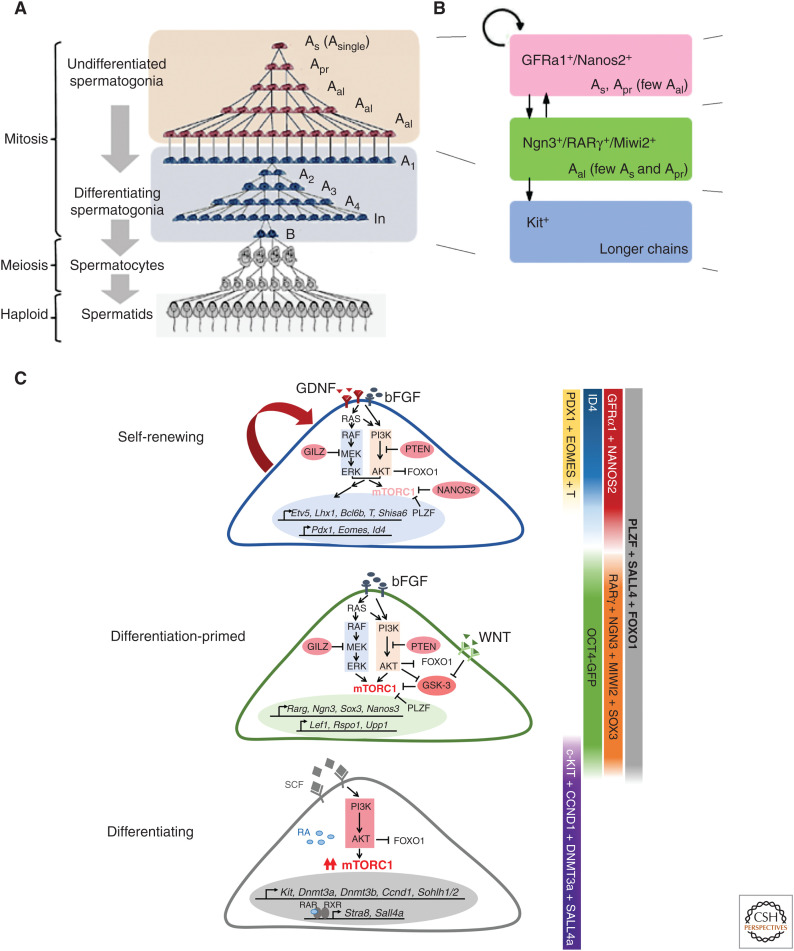

Figure 2.

Heterogeneous composition of spermatogonia and their regulation. (A) Spermatogenic cell types observed in the testis of mature mice, showing characteristic syncytial formation. Undifferentiated spermatogonia, responsible for the vast stem cell functionality, are heterogeneous in the number of interconnected cells. (B) A rough description of the spermatogonial composition based on gene expression. GFRα1+/Nanos2+ cells are the primary self-renewing population in homeostasis; Ngn3+/RARγ+/Miwi2+ cells are differentiation-primed while retaining the stem cell potential; Kit+ cells (i.e., differentiating spermatogonia) are essentially committed for differentiation and unidirectionally proceed toward meiosis. (C) Schematic illustrations summarizing the identified molecular pathways regulating the self-renewing, primed, and committed fractions of spermatogonia. (A adapted from data in Yoshida 2016. C adapted from data in La and Hobbs 2019.)

Classically, SSCs were thought to be identical to As cells (Huckins 1971a,b; Oakberg 1971; de Rooij 1973; Meistrich and van Beek 1993). This paradigm has been challenged by observations that Apr and Aal spermatogonia give rise to As cells through fragmentation by ICB breakdown, filmed in intravital imaging studies (Nakagawa et al. 2010; Hara et al. 2014), and that As cells are heterogeneous in gene expression, some of which are already destined to differentiation (Nakagawa et al. 2010; Lord and Oatley 2017; Yoshida 2019). Although the identity and behavior of SSCs remain to be fully elucidated, a number of SSC-related signature genes have been identified that can discriminate SSCs among numerous spermatogonia, and define multiple transcriptional and functional states within Aundiff (for reviews, see Lord and Oatley 2017; La and Hobbs 2019; Yoshida 2019). This view has been reinforced much further by single-cell RNA-seq analyses, which, however, lose the topological information of As, Apr, or Aal (Hammoud et al. 2015; Hermann et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2018; Green et al. 2018; La et al. 2018; Suzuki et al. 2019).

Expression of GFRα1 defines a small fraction of Aundiff harboring SSC functionality, comprised mainly of As and Apr along with few Aal (Fig. 2B; Meng et al. 2000; Hofmann et al. 2005; Nakagawa et al. 2010; Hara et al. 2014). GFRα1+ cells (largely Nanos2+), although self-renewing their population, give rise to GFRα1− Aundiff (largely, Ngn3+, Miwi2+, RARγ+); GFRα1− Aundiff are primed to differentiation and rarely contribute to the self-renewing pool in homeostasis (Fig. 2B; Yoshida et al. 2004; Nakagawa et al. 2007, 2010; Sada et al. 2009; Gely-Pernot et al. 2012; Ikami et al. 2015; Carrieri et al. 2017). GFRα1− Aundiff further differentiate to Kit+ “differentiating spermatogonia” that are committed to differentiate undergoing a defined series of mitotic divisions (through stages called A1, A2, A3, A4, intermediate [In], and B spermatogonia) (Fig. 2A,B; Russell et al. 1990; Schrans-Stassen et al. 1999; Ohbo et al. 2003). GFRα1+ cells are further heterogeneous in gene expression, represented by the restricted expressions of genes including Eomes, Pdx1, T, or Shisa6 in similar subfractions of the GFRα1+ population; the heterogeneity of GFRα1+ cells are further represented by variable levels of Id4 expression (Fig. 2C; Helsel et al. 2017; Tokue et al. 2017; Yoshida 2018b, 2019; La and Hobbs 2019; Sharma et al. 2019).

Many intra- and extracellular pathways regulating these self-renewing, primed, and committed states of spermatogonia have been identified at a molecular level (Fig. 2C). Briefly, glial cell–derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) play a crucial role to support the self-renewing population expressing GFRα1, a receptor component for GDNF ligand. Wnt/β-catenin signal inclines the cells toward a differentiation-primed, GFRα1− state (Takase and Nusse 2016; Chassot et al. 2017; Tokue et al. 2017). Retinoic acid (RA) induces the differentiation of GFRα1− cells to become Kit+, mediated by an RA receptor, RARγ (Gely-Pernot et al. 2012; Ikami et al. 2015). RARα also plays auxiliary roles here (Lord et al. 2018). These extracellular signals affect the intracellular machineries, for example, MAPK, PI3K-AKT, β-catenin, RAR, and mTOR pathways (Fig. 2C). I refer to several reviews for detailed mechanism of SSC regulation (Song and Wilkinson 2014; Yoshida 2018a, 2019; La and Hobbs 2019), while in this review I will focus on the stem cell behavior and regulation within the tissue contexts.

OPEN NICHE MICROENVIRONMENT SUPPORTING SSCs

SSCs (e.g., GFRα1+ spermatogonia) are found scattered within the basal compartment of the seminiferous tubules, intermingled among their differentiating progeny (Fig. 3A,B; Hara et al. 2014; Ikami et al. 2015). Further, they actively move, weaving in between Sertoli cells and other spermatogonia, as filmed using intravital live imaging (Fig. 3C; Hara et al. 2014). These observations are at odds with the traditional view of stem cells being tethered to definitive niche domains, although SSCs in the basal compartment show some degree of preferential localization to an area facing the interstitium and accompanying vasculature (arterioles and venules) (Chiarini-Garcia et al. 2001, 2003; Yoshida et al. 2007b; Hara et al. 2014).

Figure 3.

Open niche properties of seminiferous tubules. (A) A whole-mount immufluorescence of a part of seminiferous tubules stained for GFRα1. Note that GFRα1+ spermatogenic stem cells (SSCs) are scattered over the basal compartment. (B) A higher magnification view of a part of an adult seminiferous tubles, stained for GFRα1+ (magenta), Ngn3-GFP+ (green), and Kit+ (blue) in the basal compartment. Note that these cells are intermingled at a single-cell level. (C) Trajectories of Gfrα1-GFP+ cells in an intact testis recorded for 48 h by intravital live-imaging. Trajectories are overlain on the first frame in different colors for individual GFRα1+ Aundiff. Asterisks indicate the initial positions. (D) An image of a whole-mount seminiferous tubule after immunofluorescence (IF), in which positions of GFRa1+ cells are shown in magenta. White and gray lines alongside the tubules indicate 1-mm-long segments, containing the indicated numbers of GFRa1+ cells, showing local fluctuation in the SSC density. (E) Highly constant average density over continual segments more than 10 mm long. Horizontal lines indicate the average values. Scale bars, 50 µm. (Panels A–E from data in Hara et al. 2014, Ikami et al. 2015, and Kitadate et al. 2019.)

The traditional view is that the ligands supporting the stem cell self-renewal show restricted spatial distribution within the defined niche domain. However, in mouse seminiferous tubules, distribution of GDNF and FGF—ligands supporting the SSC self-renewal—are not restricted to particular regions. Rather, they are distributed over a wide area where SSCs and their differentiating progenies are both located in an intermingling fashion. Similarly, differentiation-promoting factors (e.g., Wnt and RA) are also suggested to show uniform spatial distribution. Interestingly, GDNF, Wnt, and RA all show temporal fluctuation with different timing in accordance with the seminiferous epithelial cycle, which is a temporally periodic progression of spermatogenesis (Russell et al. 1990; Sato et al. 2011a; Hogarth et al. 2015; Endo et al. 2017; Tokue et al. 2017; Sharma and Braun 2018; Yoshida 2018a). Therefore, the extracellular microenvironments promoting self-renewal and differentiation are not separated spatially, despite being separated temporally to some extent. Therefore, both SSCs and differentiating cells are quite likely to be exposed to the same extracellular signals (for review, see Yoshida 2018a).

In these tissue contexts, nevertheless, SSCs preserve homeostasis by maintaining their own population, giving rise to differentiating cells to replace the fully differentiated cells that eventually leave the tissue. In particular, despite local fluctuations, the average density of SSCs (i.e., number of SSCs per unit length of tubule) is kept within a small range over the entire length of the tubule, which does not change largely during aging or does not vary between individuals (Fig. 3D,E; Kitadate et al. 2019). Such microenvironments harboring scattered and migrating stem cells are generally referred to as “facultative” or “open” niches with emphasis on their anatomical or functional characteristics, respectively (Fig. 4B), in contrast to traditional “closed” or “definitive” niches, which gather stem cells and regulate their fates locally (Fig. 4A; Morrison and Spradling 2008; Stine and Matunis 2013; Yoshida 2018a).

Figure 4.

Closed/definitive versus open/facultative niche microenvironments. (A) Closed/definitive niche. Self-renewing cells (magenta) are exclusively located in the anatomically defined niche area where ligand(s) promoting self-renewal is concentrated (orange). Once cells move (or pushed) out of this area, they undergo differentiation, leading to a spatial recapitulation of the order of differentiation steps (from magenta to green and to blue, in this case). Here, cells directionally move slowly away from the niche. (B) An open/facultative niche. Self-renewing cells (magenta) are intermingled with differentiation-primed (green) and committed (blue) progenies, in area where ligand(s) for self-renewal shows a widespread distribution (orange). To maintain such tissue organization under the dynamics of population asymmetry, stem cells must migrate actively to continually interchange their positions.

ADVANTAGES OF MOUSE SPERMATOGENESIS FOR STEM CELL RESEARCH

Before describing the SSC dynamics observed in the open niche microenvironment of seminiferous tubules, it is worth emphasizing that mouse spermatogenesis has several practical advantages for the study of tissue stem cells (Yoshida 2012). First, as described earlier, based on the uniform structure of seminiferous tubules with constant diameter and virtually infinite length, the function of SSCs can be analyzed in a highly reproducible and quantitative fashion using whole-mount preparation of seminiferous tubules (Huckins and Kopriwa 1969). Second, the progeny of differentiating cells originating from a single SSC, or a clone, remain clustered within the tubules for more than a month until they leave the tissue, enabling precise identification of the clonal cohort (Nakagawa et al. 2007). Third, germ cells are dispensable for the basic framework of the tubules and for the survival or health of individuals, thereby enabling an easy assessment of the impact of depletion or other perturbation of SSCs. Fourth, in addition to lineage tracing of pulse-labeled SSCs using inducible Cre-loxP systems (e.g., Nakagawa et al. 2007), other key technologies including SSC transplantation into germ cell–depleted host testes (Brinster and Avarbock 1994; Brinster and Zimmermann 1994), spermatogonia culture that maintains SSC potentials (Kanatsu-Shinohara et al. 2003; Kubota et al. 2004), intravital live-imaging (Yoshida et al. 2007b), and ex vivo seminiferous tubule organ culture (Sato et al. 2011b; Komeya et al. 2016) have been established.

Taking advantages of these properties, studies of mouse SSCs have revealed a number of key dynamics and mechanisms underlying tissue homeostasis and regeneration. In this review, I will describe how the principles/rules/mechanisms that have emerged from the study of SSCs enable a fuller understanding of, and insights to, tissue stem cells in general.

SSC DYNAMICS THAT ARE COMMONLY OBSERVED IN OTHER TISSUES

How do SSCs support homeostasis (i.e., continual spermatogenesis) and regeneration by controlling the balance between self-renewal and differentiation? The analysis of the fate of individual SSCs in vivo has revealed the population dynamics of SSCs. Some of these are found to be generic for a range of tissue stem cells including those supported by closed niches.

Population Asymmetry

By pulse-labeling SSCs using tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase via a Gfrα1-CreER allele, their clonal fate behaviors have been analyzed at a high resolution, including the differentiation status of individual cells within SSC-derived clones (Hara et al. 2014). SSCs follow highly variable fates. Some SSCs give rise to more than one SSC, whereas others produce only differentiating cells. However, their average behavior preserves perfect stem cell dynamics at the population level; that is, they continually self-renew and produce differentiating cells as schematically shown in Figure 5B (Hara et al. 2014). Reinforcing an earlier study performed at a population level (Nakagawa et al. 2007), this scheme is consistent with other studies that label different fractions of Aundiff (e.g., Nanos2+, Bmi1+, or Pax7+) (Sada et al. 2009; Aloisio et al. 2014; Komai et al. 2014). Therefore, the balance between self-renewal and differentiation is achieved at the population level via collective behavior of SSCs (a dynamic called “population asymmetry”) rather than at the single-cell level through invariable asymmetric division (“division asymmetry”) (Fig. 5A; Klein and Simons 2011).

Figure 5.

Division asymmetry versus population asymmetry. (A) A diagram of the dynamics of division asymmetry. All the divisions of stem cells (cells in self-renewing compartment) invariantly give rise to the asymmetric outcome with one self-renewing and one differentiating daughter cell. As a result, the clonal repertoire of the self-renewing pool (indicated by different colors) remains unchanged over time. (B) A diagram of population asymmetry. The balance between self-renewal and differentiation is achieved at the population level so that the number of self-renewing cells is kept constant: Each stem cell division gives rise to variable outcomes, that is, two self-renewing daughters (magenta arrows), two differentiating daughters (blue arrows), or one self-renewing and one differentiating daughter (gray arrows). In this scheme, the stem cells’ clonal repertoire drifts over time, becoming dominated by fewer clones, and eventually being dominated by a single clone. (Adapted, with permission, from Yoshida 2019.)

Neutral Competition and Clonal Drift

Strikingly, the highly variable fate of individual SSC clones is found to be predicted precisely by a minimal mathematical model, in which every SSC is assumed to follow the same probabilistic fate behavior (i.e., to proliferate as SSCs or to differentiate at defined probabilities) (Klein et al. 2010; Hara et al. 2014; Chatzeli and Simons 2020). As a result, during homeostasis, SSCs show “neutral competition” so that the SSC repertoire will be reduced over time, following the dynamics of “neutral drift” (Klein and Simons 2011; Simons and Clevers 2011). Population asymmetry and neutral competition, first described in stem cell systems in interfollicular epidermis (IFE), small intestine epithelium, as well as in mouse spermatogenesis (Clayton et al. 2007; Nakagawa et al. 2007; Doupé et al. 2010; Klein et al. 2010; Lopez-Garcia et al. 2010; Snippert et al. 2010), have been also found in other cycling tissues and recognized as universal rules (Klein and Simons 2011; Krieger and Simons 2015; Chatzeli and Simons 2020).

Context Dependence

Tissue stem cells play roles not only in the maintenance of homeostasis, but also in different contexts such as growth and regeneration (i.e., tissue repair after insult or restoration of tissue functions after transplantation). Contrary to the classical thought that stem cells may be an unequivocally definable entity regardless of context, in mouse spermatogenesis fractions of Aundiff flexibly change their behavior in a context-dependent manner (Nakagawa et al. 2007; Yoshida et al. 2007a). In particular, the Ngn3+/Miwi2+ fraction of Aundiff, which barely self-renew but rather differentiate in homeostatic conditions, can convert reversibly to the GFRα1+ state and significantly contribute to the self-renewing pool after insult by a cytotoxic reagent (busulfan) or after transplantation into the seminiferous tubules of host mice (Nakagawa et al. 2007, 2010; Carrieri et al. 2017). Such a flexible change in fate of differentiation-primed cells was first discovered in Drosophila female and male germlines (Brawley and Matunis 2004; Kai and Spradling 2004), followed by mouse spermatogenesis (Nakagawa et al. 2007). Then, such context-dependent reversion of some differentiation-destined—and even terminally differentiated—cells to the self-renewing stem cell pool during regeneration has been found to be a generic feature among many stem cell–supported tissues, in particular a wide range of epithelial tissues, for example, intestinal epithelium, hair follicle and IFE, and lung bronchioalveolar epithelium (reviews include Beumer and Clevers 2016; Santos et al. 2018; de Sousa E Melo and de Sauvage 2019; Das et al. 2020).

Dynamic Heterogeneity

There is current interest in whether similar state changes also occur during the homeostatic context. By intravital live imaging, GFRα1+ Aundiff were found to interconvert between distinct topological states of As and syncytia (Apr and Aal) through incomplete division (as a result of incomplete cytokinesis) and syncytial fragmentation (as a result of ICB breakdown) (Hara et al. 2014). This has led to the proposal of “dynamic heterogeneity” in which stem cells maintain their pool through continual interconversion between different states (Krieger and Simons 2015). The observed heterogeneous gene expression within the GFRα1+ population (Helsel et al. 2017; La et al. 2018; Yoshida 2019) motivates current investigators to ask whether, and how, SSCs interconvert between multiple transcriptional states during homeostasis. In intestinal crypts, similar state changes of epithelial stem cells during homeostasis is observed to occur in a manner that is closely related to the position within the crypt (Takeda et al. 2011; Buczacki et al. 2013).

SSC DYNAMICS THAT ARE CHARACTERISTIC OF MOUSE SPERMATOGENESIS

In addition to generic stem cell dynamics, SSC behavior also illustrates the characteristic features of an open niche-supported stem cell system.

Stem Cell Motion

Among the most striking features of SSCs that distinguish them from many other tissue stem cells is their prominent motion, observed by intravital live-imaging studies (Fig. 3C; Yoshida et al. 2007b; Hara et al. 2014). In the basal compartment of seminiferous tubules, Gfrα1-GFP+ cells, many of which are singly isolated As cells or Apr, continually move around and weave their way between Sertoli cells and differentiating spermatogonia (Yoshida et al. 2007b; Hara et al. 2014). Interestingly, GFRα1+ spermatogonia are sparsely scattered and show seemingly random tragedies rather than collective or directional movements, while showing some preference to areas near the interstitium and vasculature. Some GFRα1+ SSCs translocate between vasculature-related regions over a distance of 100 µm within a day or two without losing their stem cell potential or signature gene expression (e.g., Gfrα1). Compared to GFRα1+ cells, Ngn3+ cells are less motile and tend to stay around the vasculature-proximal region (Yoshida et al. 2007b). On differentiating to Kit+ differentiating spermatogonia, they leave these areas to spread evenly over the basal compartment (Yoshida et al. 2007b). Then, when meiosis starts after six rounds of mitotic divisions of differentiating spermatogonia, the cells (spermatocytes) dispatch the basal membrane and translocate vertically into the adluminal compartment. Therefore, SSCs are much more motile than their differentiating progenies.

Compared with the prominent motion of GFRα1+ SSCs over long distances in between differentiating cells, the extent of the motion of stem cells in tissues harboring definitive niches is much more limited within the niche domains, including Drosophila testis and ovary (Sheng et al. 2009; Morris and Spradling 2011), mouse intestinal crypt (Ritsma et al. 2014), hair follicle bulge (Rompolas et al. 2012, 2013), and basal layer of IFE (Rompolas et al. 2016), as described later.

Differential Competence to Extracellular Signals

Within an open niche of seminiferous tubules, fates of SSCs are regulated by a number of extracellular signals (Fig. 2C). As described earlier, GDNF, WNT, and RA show spatially uniform distribution, indicating that SSCs and progenitors are likely to be equally exposed to these factors. However, SSCs show asymmetric fate outcome, for example, self-renewal and differentiation, in a balanced manner. It has turned out that such a different outcome is due to the differential susceptibility to extracellular signals (Yoshida 2018a). First, Shisa6, a cell-intrinsic WNT inhibitor, is expressed in a subfraction of GFRα1+ cells, which gain resistance to the differentiation-inducing WNT signal (Tokue et al. 2017). Second, when GFRα1+ cells differentiate to GFRα1−, they lose the responsiveness to the self-renewal-promoting ligand, GDNF, as GFRα1 is an essential component of GDNF receptor (Jing et al. 1996). Finally, on losing GFRα1 expression, cells gain the expression of RARγ, and therefore the responsiveness to RA to differentiate to Kit+ (Ikami et al. 2015). Thus, the asymmetric fate outcome of SSCs is based on the heterogeneous susceptibilities to widely distributed ligands.

Competition for Widely Distributed Ligands that Promote Self-Renewal

Within a classic view, stem cell number is kept constant because of limited access to the spatially definitive niche domain, in which the self-renewing factor(s) is present in high concentration (reviews include Watt and Hogan 2000; Fuller and Spradling 2007; Morrison and Spradling 2008; Inaba et al. 2016). In open niches, however, the mechanisms controlling stem cell number (i.e., density) had been unknown. Recently, a mechanism called “mitogen competition” has been proposed to explain the SSC homeostasis in seminiferous tubules (Fig. 6; Kitadate et al. 2019). In this model, motile SSCs effectively compete with each other, without direct cell–cell interactions, by consuming a limited supply of a ligand promoting self-renewal or “mitogen.” In particular, SSCs are suggested to compete for FGFs that are secreted from a subset of lymphatic endothelial cells and distributed broadly over the open niche microenvironment (e.g., vasculature-proximal area of the basal compartment) (Fig. 6A). SSCs that have consumed higher amounts of FGFs would express higher levels of FGF target genes and self-renew with high probability, whereas those that have consumed less FGF would tilt toward differentiation as a result of the expression of differentiation-related genes (Fig. 6B). This theory is primarily based on the linear correlation between SSC density and dose of FGF ligands (Kitadate et al. 2019). It is further supported by the observation that the characteristic oscillating kinetics during the recovery of SSCs after experimental reduction are predicted quantitatively by a simple model based on the mechanism of mitogen competition (Jörg et al. 2019; Kitadate et al. 2019; Chatzeli and Simons 2020). This simple and therefore robust mechanism, which warrants future critical evaluations, would possibly be paradigmatic for stem cell regulation in other open niche-supported tissues.

Figure 6.

Regulation of spermatogenic stem cells (SSCs) by “mitogen competition” in the basal compartment of seminiferous tubules. (A) Schematic of the open niche microenvironment of the basal compartment of seminiferous tubules, regulating GFRa1+ SSCs. A subset of lymphatic endothelial cells and a few interstitial cells (green) fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) (e.g., FGF5, FGF4, FGF8, and possibly others) are produced and secreted to the basal compartment. FGFs, which have an affinity to the basement membrane, are taken up and consumed by motile GFRa1+ SSCs and biases their fate behavior in a concentration-dependent manner (see B). This mechanism self-organizes a density homeostasis of SSCs as well as higher local SSC density near the FGF source. (B) In this scheme, SSCs effectively compete with each other for a limited supply of FGF. SSCs that consume larger amounts of FGF will show higher expression of cell-cycle-promoting and antidifferentiation genes and lower expression of differentiation-promoting genes, tilting their fate toward proliferation without differentiation. SSCs consuming smaller amounts of FGF, on the other hand, will show opposite patterns of target genes, tilting their fate toward differentiation. (Figure reprinted from Kitadate et al. 2019 under the terms of the Creative Commons CC-BY license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.)

UNITY AND DIVERSITY OF STEM CELL NICHE SYSTEMS

As described above, the study of the mouse SSC-niche system has depicted a number of key features, some of which are generic among tissues, while others emphasize the uniqueness of this open niche-supported system. Here, I would suggest that tissue stem cell systems supported by closed/definitive and open/facultative niches may not be, by nature, as different as they might seem. Rather, tissue stem cells share a number of common properties.

Unity

Of particular note, the homeostatic stem cell clone dynamics in different tissues (including mouse small intestinal epithelium, IFE, esophageal epithelium, mammary gland, and spermatogenesis) can be predicted quantitatively by essentially the same class of simple mathematical models that are based on the assumption that stem cells all follow equivalent stochastic (i.e., probabilistic) fate behavior (Klein and Simons 2011; Krieger and Simons 2015; Chatzeli and Simons 2020). This striking finding indicates that stochastic fate behavior (to undergo self-renewal or differentiation at defined probabilities) may be a generic property of many, if not all, tissue stem cells. In addition, tissue stem cells may flexibly transit between multiple states and support tissue homeostasis and regeneration through interplay with external cues from the niche microenvironments.

Diversity

Despite the generic principles of fate stochasticity, stem cell niche systems are indeed highly divergent between different tissue types. Such characteristics may, in principle, reflect the different degrees of (1) spatial distribution of ligand(s) supporting the stem cell self-renewal, and (2) the motility of cells in the self-renewing compartment. These key parameters vary in a mutually correlated and coordinated manner in particular tissue contexts, which diverge according to the shape and the size of the tissues, the number of the stem cells, the nature of niche cells and the distribution of stem cell–regulating ligands, and the modes of stem cell niche interactions, as described below for several well-studied tissues and as schematically shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

A conceptual presentation of tissue stem cell niche systems. Plots of investigated examples of tissue stem cell niche systems on a hypothetical coordinate plane, based on the considered degrees of ligand localization (x-axis) and stem cell motility (y-axis). Drosophila oogenesis in ovary (purple) and spermatogenesis in testis (blue), mouse intestinal stem cells in the crypt (cyan), mouse hair follicle stem cells in the bulge (green), mouse interfollicular epidermis (yellow), mouse hematopoietic stem cells in bone marrow (orange), and mouse spermatogenesis (red) are shown. See text for details. (Dm.) Drosophila, (Mm.) mouse.

A SPECTRUM OF TISSUE STEM CELLS WITH VARYING LIGAND LOCALIZATION AND STEM CELL MOTILITY

In Figure 7, I will try to show a conceptual spectrum of a number of stem cell–supported tissues based on the considered degrees of ligand localization (x-axis) and stem cell motility (y-axis). Here, the x-axis value is based on the extent of spatial distribution of ligands supporting the stem cell self-renewal and the sharpness of their border. The smaller the distributing area is and the sharper the border is, the “more localized” this parameter will be (plotted leftward), while it will be plotted rightward or “more diffuse” when the ligand is distributed in a widespread and diffusive manner. The y-axis value primarily reflects how freely stem cells move over a long distance without losing their stem cell properties. It will be plotted toward the bottom if stem cell motion is restricted, for example, by anchoring to a particular niche structure (e.g., niche cells or extracellular matrixes) or through attachment with the neighboring cells.

These features, in combination, shape the characteristics of stem cell niche interactions in different tissues. Tissues plotted in the bottom left region are more likely supported by a “closed/definitive niche.” Conversely, “open/facultative niche”–supported tissues are found toward the top right. I will give a short overview of a number of tissue stem cell niche systems from this point of view.

Drosophila Ovary and Testis

Among the tissues investigated in depth, the strongest restrictions with regard to both ligand localization and stem cell motility are observed in Drosophila germ line stem cells (GSCs) (shown in purple and blue, respectively, for female and male in Fig. 7; Yamashita et al. 2005; Fuller and Spradling 2007; Spradling et al. 2011; Nelson et al. 2019). Female and male Drosophila gonads develop specialized niche cells (cap and hub cells, respectively), which secrete ligands for stem cell maintenance (e.g., Dpp and Upd, respectively) that act in close proximity and house a small number of GSCs (∼2–3 and ∼6–9 stem cells per niche, respectively). GSCs and niche cells are attached tightly via adherens junctions, which further constrain the orientation of the mitotic spindles of GSCs (in females, this is mediated by a specialized structure called the spectrosome [Lin et al. 1994]). Furthermore, male GSCs extrude nanotubes into niche cells (Inaba et al. 2015). Accordingly, the niche domain is tightly defined within a single-cell distance from the niche cells, and GSCs undergo asymmetric divisions with high probabilities. However, even in these tissues, stem cell division occasionally gives rise to a symmetric outcome of a pair of differentiating or self-renewing daughter cells, indicating infrequent rearrangement of GSCs in this definitive niche (Sheng and Matunis 2011).

Intestinal Stem Cells in the Crypt

While considered to be a typical closed/definitive niche, mammalian intestinal crypts show somewhat weaker constraints on intestinal stem cells (ISCs), compared with Drosophila GSCs (cyan in Fig. 7; Clevers 2013; Gehart and Clevers 2019). Typically, ∼16 cells showing a stem cell gene expression signature (including Lgr5) lie intermingled among Paneth cells in the crypt base, which produce Wnts, the major ligands that promote self-renewal acting in a short range (Sato et al. 2011a; Farin et al. 2016). Wnts, as well as R-spondins, are also produced by mesenchymal telocytes, which are also located in proximity to the ISCs across the basement membrane (Santos et al. 2018). No differentiating cells are found within this region (except for Paneth cells and their progenitors), and stem cell properties cannot be maintained outside this region. However, unlike the Drosophila gonads in which stem cell motility is highly restricted, stem cells relocate rather freely and actively within the definitive niche domain, leading to typical dynamics of population asymmetry and rapid clonal drift within a niche (Lopez-Garcia et al. 2010; Snippert et al. 2010; Ritsma et al. 2014; Chatzeli and Simons 2020).

Hair Follicle Bulge

A more relaxed stem cell niche system is observed in the hair follicle stem cells located in the bulge, which give rise to multiple cell types to comprise the hair and accessory structures (Taylor et al. 2000; Alonso and Fuchs 2003; Hsu et al. 2014; Fujiwara et al. 2018). The hair follicle bulge, albeit its greater spatial extent than the crypt base of intestinal epithelium, may still be better considered as a closed/definitive niche (green in Fig. 7). A single bulge houses hundreds of stem cells, which appear to be heterogeneous depending largely on their position within the bulge region, as suggested from the gene expression and fate behaviors (Rompolas et al. 2012, 2013; Rompolas and Greco 2014; Fujiwara et al. 2018; Rognoni and Watt 2018). The stem cell subsets and the source of the ligands (e.g., Wnts, Tgfβ, and BMPs) show intricate but well-organized spatial heterogeneity within a bulge, as is being realized by combining single-cell transcriptome with tissue immunostaining (Joost et al. 2016). The stem cells are also found to be motile in the bulge to a limited extent (Rompolas et al. 2012).

Interfollicular Epidermis

In the IFE of mammalian skin, the domain of stem cell localization may not be definable. Indeed, identity of IFE stem cells has not reached full agreement. The basal cells might compose a single self-renewing pool that supports the homeostasis as an entirety, while some degree of functional and transcriptional heterogeneity/hierarchy has been also evidenced (Jones et al. 2007; Mascré et al. 2012; Sada et al. 2016; Fujiwara et al. 2018; Tabib et al. 2018). Inhomogeneous microenvironment has been implicated in relation to the undulation of basement membrane particularly in humans (Jones et al. 1995; Jensen et al. 1999), which can be recapitulated by artificial culture substrates (Mobasseri et al. 2019). Although these findings suggest the role of mechanical factor to the stem cell–supporting microenvironment, a defined niche domain with localized ligand distribution has not been identified. Rather, this tissue (in particular that of mice showing flattened architecture) would be better considered to be supported by an open niche with virtually infinite spatial extent (yellow in Fig. 7). Here, stem cell clones show population asymmetry and stochastic clonal drift (Clayton et al. 2007; Doupé et al. 2010; Rompolas et al. 2016; Chatzeli and Simons 2020). However, unlike SSCs in seminiferous tubules, the IFE stem cells in the skin develop coherent clones with minimal intermingling. This indicates low motility of IFE stem cells on the basement membrane with rare rearrangements between neighbors. On differentiation to keratinocytes, cells lose the contact with the basement membrane and move vertically.

Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Bone Marrow

Mammalian bone marrow is considered to provide a typical facultative/open niche microenvironment for hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (orange in Fig. 7; Morrison and Spradling 2008; Stine and Matunis 2013). Quite a small number of HSCs, in particular long-term HSCs, are scattered over the marrow, making primary contact with heterogeneous stromal cells secreting a set of ligands (e.g., SCF, CXCL12, thrombopoietin) located perivascularly (Nagasawa et al. 2011; Morrison and Scadden 2014; Crane et al. 2017; Baryawno et al. 2019). Interestingly, however, such microenvironments (i.e., the contact to these niche cells) appear to harbor not only HSCs but also their progenitors, which are present in greater numbers than stem cells. In addition, because of the difficulty in observing the bone marrow and visualizing HSCs live, in situ analyses (in particular the live-imaging studies) of HSCs has been limited to particular situations such as posttransplantation (Lo Celso et al. 2009). Therefore, particular microenvironment supporting HSCs and their behaviors therein warrant investigation based on the success of highly specific visualization of HSCs making use of specific markers, for example, α-catulin or Hoxb5 (Acar et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2016). Although HSCs could be tethered to an unidentified definitive region where ligands are concentrated, it may be also possible that the ligands are distributed widely and homeostasis of motile HSCs is achieved by a mechanism similar to SSCs.

Mouse Spermatogenesis

Finally, mouse spermatogenesis may be plotted on the top right corner of the coordinate plane, in the opposite position to the Drosophila gonads (red in Fig. 7). In the basal compartment of seminiferous tubules, in which the ligands (e.g., GDNF and FGFs) are widely supplied, sparsely distributed SSCs show active migration to a much larger extent compared with tissues described above, leading to considerable intermingling between stem cell clones (Nakagawa et al. 2007; Klein et al. 2010; Hara et al. 2014; Kitadate et al. 2019). However, the ligand supply is not perfectly uniform: the FGF-producing cells show a biased localization to extratubular interstitium, in which SSC density is highest (Chiarini-Garcia et al. 2001, 2003; Yoshida et al. 2007b; Kitadate et al. 2019). Therefore, some degree of definitive/closed niche-like property is also evident in mouse testis.

FUTURE QUESTIONS REGARDING SSC DYNAMICS IN SEMINIFEROUS TUBULES

Based on the findings in mouse spermatogenesis, the unity and diversity of tissue stem cell systems have been discussed, with a special emphasis on the spatial (structural) characteristics in the niche microenvironment and the motility of stem cells therein. In addition, it should be vital to point out the potential importance of temporal changes. Tissue-level homeostasis over large time and spatial scales may be based on local and short-term fluctuations.

There is already evidence that mouse spermatogenesis involves a spatiotemporally coordinated pattern of periodic change, called the “seminiferous epithelial cycle” and “spermatogenic wave” (Russell et al. 1990; Yoshida 2019). Within a short segment of a tubule, generation of differentiating spermatogonia from the Aundiff compartment and subsequent differentiation steps occur synchronously in a temporally periodic manner, showing an interval of 8.6 days in the case of mice (cycle) (Leblond and Clermont 1952; Oakberg 1956). Furthermore, the phase of this “cycle” is recapitulated spatially along the length of the tubule, resulting in a traveling wave-like spatiotemporal orchestration (wave) (Perey et al. 1961).

Historically, cycle and wave have provided invaluable clues to researches on the fate of SSCs based on static information. The data were obtained from fixed tissues (including S-phase labeling) when cell-fate tracing within a tissue (e.g., live imaging or lineage tracing) was not possible (Huckins 1971b; Meistrich and van Beek 1993). Application of recent analytical techniques will throw light on the SSC dynamics within a temporally fluctuating niche microenvironment. Indeed, production of GDNF in Sertoli cells oscillates in a temporally periodic manner in accordance with the cycle (Sato et al. 2011a; Tokue et al. 2017; Sharma and Braun 2018). Further, hair follicle bulge stem cells change their properties periodically to promote the hair cycle (Rompolas and Greco 2014; Lay et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016; Adam et al. 2018). Similar temporal fluctuation could be involved in other tissues, although it might be hidden by the lack of clear local synchronization or spatial pattern. In any case, the issue of time dependence will enhance our understanding of tissue stem cells.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this review, I have summarized the contributions made by the study of mouse spermatogenesis to a general understanding of tissue stem cell niche systems. Based on the biological and technical advantages of the system, mouse spermatogenesis will continue to provide important new insights into the properties of stem cells and their regulation by the niche.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to all our laboratory members and colleagues for the past and ongoing exciting collaborations and discussions. Fruitful comments from Ben Simons and Hironobu Fujiwara on this manuscript are really appreciated. Researches conducted in our laboratory and described in this article have been supported in part by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the PRESTO program from Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), and the AMED-CREST program from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED). The author has no conflict of interests to declare.

Footnotes

Editors: Cristina Lo Celso, Kristy Red-Horse, and Fiona M. Watt

Additional Perspectives on Stem Cells: From Biological Principles to Regenerative Medicine available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Acar M, Kocherlakota KS, Murphy MM, Peyer JG, Oguro H, Inra CN, Jaiyeola C, Zhao Z, Luby-Phelps K, Morrison SJ. 2015. Deep imaging of bone marrow shows non-dividing stem cells are mainly perisinusoidal. Nature 526: 126–130. 10.1038/nature15250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam RC, Yang H, Ge Y, Lien WH, Wang P, Zhao Y, Polak L, Levorse J, Baksh SC, Zheng D, et al. 2018. Temporal layering of signaling effectors drives chromatin remodeling during hair follicle stem cell lineage progression. Cell Stem Cell 22: 398–413.e7. 10.1016/j.stem.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisio GM, Nakada Y, Saatcioglu HD, Peña CG, Baker MD, Tarnawa ED, Mukherjee J, Manjunath H, Bugde A, Sengupta AL, et al. 2014. PAX7 expression defines germline stem cells in the adult testis. J Clin Invest 124: 3929–3944. 10.1172/JCI75943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso L, Fuchs E. 2003. Stem cells of the skin epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 11830–11835. 10.1073/pnas.1734203100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baryawno N, Przybylski D, Kowalczyk MS, Kfoury Y, Severe N, Gustafsson K, Kokkaliaris KD, Mercier F, Tabaka M, Hofree M, et al. 2019. A cellular taxonomy of the bone marrow stroma in homeostasis and leukemia. Cell 177: 1915–1932.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beumer J, Clevers H. 2016. Regulation and plasticity of intestinal stem cells during homeostasis and regeneration. Development 143: 3639–3649. 10.1242/dev.133132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawley C, Matunis E. 2004. Regeneration of male germline stem cells by spermatogonial dedifferentiation in vivo. Science 304: 1331–1334. 10.1126/science.1097676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster RL, Avarbock MR. 1994. Germline transmission of donor haplotype following spermatogonial transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 91: 11303–11307. 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster RL, Zimmermann JW. 1994. Spermatogenesis following male germ-cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 91: 11298–11302. 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczacki SJ, Zecchini HI, Nicholson AM, Russell R, Vermeulen L, Kemp R, Winton DJ. 2013. Intestinal label-retaining cells are secretory precursors expressing Lgr5. Nature 495: 65–69. 10.1038/nature11965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrieri C, Comazzetto S, Grover A, Morgan M, Buness A, Nerlov C, O'Carroll D. 2017. A transit-amplifying population underpins the efficient regenerative capacity of the testis. J Exp Med 214: 1631–1641. 10.1084/jem.20161371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassot AA, Le Rolle M, Jourden M, Taketo MM, Ghyselinck NB, Chaboissier MC. 2017. Constitutive WNT/CTNNB1 activation triggers spermatogonial stem cell proliferation and germ cell depletion. Dev Biol 426: 17–27. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Chatzeli L, Simons BD. 2020. Tracing the dynamics of stem cell fate. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a036202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Miyanishi M, Wang SK, Yamazaki S, Sinha R, Kao KS, Seita J, Sahoo D, Nakauchi H, Weissman IL. 2016. Hoxb5 marks long-term haematopoietic stem cells and reveals a homogenous perivascular niche. Nature 530: 223–227. 10.1038/nature16943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zheng Y, Gao Y, Lin Z, Yang S, Wang T, Wang Q, Xie N, Hua R, Liu M, et al. 2018. Single-cell RNA-Seq uncovers dynamic processes and critical regulators in mouse spermatogenesis. Cell Res 28: 879–896. 10.1038/s41422-018-0074-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini-Garcia H, Hornick JR, Griswold MD, Russell LD. 2001. Distribution of type A spermatogonia in the mouse is not random. Biol Reprod 65: 1179–1185. 10.1095/biolreprod65.4.1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini-Garcia H, Raymer AM, Russell LD. 2003. Non-random distribution of spermatogonia in rats: evidence of niches in the seminiferous tubules. Reproduction 126: 669–680. 10.1530/rep.0.1260669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton E, Doupé DP, Klein AM, Winton DJ, Simons BD, Jones PH. 2007. A single type of progenitor cell maintains normal epidermis. Nature 446: 185–189. 10.1038/nature05574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H. 2013. The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell compartment. Cell 154: 274–284. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane GM, Jeffery E, Morrison SJ. 2017. Adult haematopoietic stem cell niches. Nat Rev Immunol 17: 573–590. 10.1038/nri.2017.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das D, Fletcher RB, Ngai J. 2020. Cellular mechanisms of epithelial stem cell self-renewal and differentiation during homeostasis and repair. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 9: e361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij DG. 1973. Spermatogonial stem cell renewal in the mouse. I: Normal situation. Cell Tissue Kinet 6: 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij DG. 2017. The nature and dynamics of spermatogonial stem cells. Development 144: 3022–3030. 10.1242/dev.146571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij DG, Russell LD. 2000. All you wanted to know about spermatogonia but were afraid to ask. J Androl 21: 776–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa E Melo F, de Sauvage FJ. 2019. Cellular plasticity in intestinal homeostasis and disease. Cell Stem Cell 24: 54–64. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupé DP, Klein AM, Simons BD, Jones PH. 2010. The ordered architecture of murine ear epidermis is maintained by progenitor cells with random fate. Dev Cell 18: 317–323. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Freinkman E, de Rooij DG, Page DC. 2017. Periodic production of retinoic acid by meiotic and somatic cells coordinates four transitions in mouse spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114: E10132–E10141. 10.1073/pnas.1710837114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farin HF, Jordens I, Mosa MH, Basak O, Korving J, Tauriello DV, de Punder K, Angers S, Peters PJ, Maurice MM, et al. 2016. Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem-cell niche. Nature 530: 340–343. 10.1038/nature16937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H, Tsutsui K, Morita R. 2018. Multi-tasking epidermal stem cells: beyond epidermal maintenance. Dev Growth Differ 60: 531–541. 10.1111/dgd.12577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller MT, Spradling AC. 2007. Male and female Drosophila germline stem cells: two versions of immortality. Science 316: 402–404. 10.1126/science.1140861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehart H, Clevers H. 2019. Tales from the crypt: new insights into intestinal stem cells. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 16: 19–34. 10.1038/s41575-018-0081-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gely-Pernot A, Raverdeau M, Célébi C, Dennefeld C, Feret B, Klopfenstein M, Yoshida S, Ghyselinck NB, Mark M. 2012. Spermatogonia differentiation requires retinoic acid receptor γ. Endocrinology 153: 438–449. 10.1210/en.2011-1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CD, Ma Q, Manske GL, Shami AN, Zheng X, Marini S, Moritz L, Sultan C, Gurczynski SJ, Moore BB, et al. 2018. A comprehensive roadmap of murine spermatogenesis defined by single-cell RNA-Seq. Dev Cell 46: 651–667.e10. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud SS, Low DH, Yi C, Lee CL, Oatley JM, Payne CJ, Carrell DT, Guccione E, Cairns BR. 2015. Transcription and imprinting dynamics in developing postnatal male germline stem cells. Genes Dev 29: 2312–2324. 10.1101/gad.261925.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Nakagawa T, Enomoto H, Suzuki M, Yamamoto M, Simons BD, Yoshida S. 2014. Mouse spermatogenic stem cells continually interconvert between equipotent singly isolated and syncytial states. Cell Stem Cell 14: 658–672. 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsel AR, Yang QE, Oatley MJ, Lord T, Sablitzky F, Oatley JM. 2017. ID4 levels dictate the stem cell state in mouse spermatogonia. Development 144: 624–634. 10.1242/dev.146928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann BP, Mutoji KN, Velte EK, Ko D, Oatley JM, Geyer CB, McCarrey JR. 2015. Transcriptional and translational heterogeneity among neonatal mouse spermatogonia. Biol Reprod 92: 54 10.1095/biolreprod.114.125757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann MC, Braydich-Stolle L, Dym M. 2005. Isolation of male germ-line stem cells; influence of GDNF. Dev Biol 279: 114–124. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth CA, Arnold S, Kent T, Mitchell D, Isoherranen N, Griswold MD. 2015. Processive pulses of retinoic acid propel asynchronous and continuous murine sperm production. Biol Reprod 92: 37 10.1095/biolreprod.114.126326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu YC, Li L, Fuchs E. 2014. Emerging interactions between skin stem cells and their niches. Nat Med 20: 847–856. 10.1038/nm.3643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckins C. 1971a. The spermatogonial stem cell population in adult rats. I: Their morphology, proliferation and maturation. Anat Rec 169: 533–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckins C. 1971b. The spermatogonial stem cell population in adult rats. II: A radioautographic analysis of their cell cycle properties. Cell Tissue Kinet 4: 313–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckins C, Kopriwa BM. 1969. A technique for the radioautography of germ cells in whole mounts of seminiferous tubules. J Histochem Cytochem 17: 848–851. 10.1177/17.12.848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikami K, Tokue M, Sugimoto R, Noda C, Kobayashi S, Hara K, Yoshida S. 2015. Hierarchical differentiation competence in response to retinoic acid ensures stem cell maintenance during mouse spermatogenesis. Development 142: 1582–1592. 10.1242/dev.118695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba M, Buszczak M, Yamashita YM. 2015. Nanotubes mediate niche-stem-cell signalling in the Drosophila testis. Nature 523: 329–332. 10.1038/nature14602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba M, Yamashita YM, Buszczak M. 2016. Keeping stem cells under control: new insights into the mechanisms that limit niche-stem cell signaling within the reproductive system. Mol Reprod Dev 83: 675–683. 10.1002/mrd.22682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen UB, Lowell S, Watt FM. 1999. The spatial relationship between stem cells and their progeny in the basal layer of human epidermis: a new view based on whole-mount labelling and lineage analysis. Development 126: 2409–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing S, Wen D, Yu Y, Holst PL, Luo Y, Fang M, Tamir R, Antonio L, Hu Z, Cupples R, et al. 1996. GDNF-induced activation of the ret protein tyrosine kinase is mediated by GDNFR-α, a novel receptor for GDNF. Cell 85: 1113–1124. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81311-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PH, Harper S, Watt FM. 1995. Stem cell patterning and fate in human epidermis. Cell 80: 83–93. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90453-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PH, Simons BD, Watt FM. 2007. Sic transit gloria: farewell to the epidermal transit amplifying cell? Cell Stem Cell 1: 371–381. 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joost S, Zeisel A, Jacob T, Sun X, La Manno G, Lönnerberg P, Linnarsson S, Kasper M. 2016. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals that differentiation and spatial signatures shape epidermal and hair follicle heterogeneity. Cell Syst 3: 221–237.e9. 10.1016/j.cels.2016.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörg DJ, Kitadate Y, Yoshida S, Simons BD. 2019. Competition for stem cell fate determinants as a mechanism for tissue homeostasis. arXiv 190103903. [Google Scholar]

- Kai T, Spradling A. 2004. Differentiating germ cells can revert into functional stem cells in Drosophila melanogaster ovaries. Nature 428: 564–569. 10.1038/nature02436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Miki H, Ogura A, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. 2003. Long-term proliferation in culture and germline transmission of mouse male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod 69: 612–616. 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitadate Y, Jörg DJ, Tokue M, Maruyama A, Ichikawa R, Tsuchiya S, Segi-Nishida E, Nakagawa T, Uchida A, Kimura-Yoshida C, et al. 2019. Competition for mitogens regulates spermatogenic stem cell homeostasis in an open niche. Cell Stem Cell 24: 79–92.e6. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AM, Simons BD. 2011. Universal patterns of stem cell fate in cycling adult tissues. Development 138: 3103–3111. 10.1242/dev.060103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AM, Nakagawa T, Ichikawa R, Yoshida S, Simons BD. 2010. Mouse germ line stem cells undergo rapid and stochastic turnover. Cell Stem Cell 7: 214–224. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komai Y, Tanaka T, Tokuyama Y, Yanai H, Ohe S, Omachi T, Atsumi N, Yoshida N, Kumano K, Hisha H, et al. 2014. Bmi1 expression in long-term germ stem cells. Sci Rep 4: 6175 10.1038/srep06175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komeya M, Kimura H, Nakamura H, Yokonishi T, Sato T, Kojima K, Hayashi K, Katagiri K, Yamanaka H, Sanjo H, et al. 2016. Long-term ex vivo maintenance of testis tissues producing fertile sperm in a microfluidic device. Sci Rep 6: 21472 10.1038/srep21472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger T, Simons BD. 2015. Dynamic stem cell heterogeneity. Development 142: 1396–1406. 10.1242/dev.101063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. 2004. Growth factors essential for self-renewal and expansion of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 16489–16494. 10.1073/pnas.0407063101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La HM, Hobbs RM. 2019. Mechanisms regulating mammalian spermatogenesis and fertility recovery following germ cell depletion. Cell Mol Life Sci 76: 4071–4102. 10.1007/s00018-019-03201-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La HM, Mäkelä JA, Chan AL, Rossello FJ, Nefzger CM, Legrand JMD, De Seram M, Polo JM, Hobbs RM. 2018. Identification of dynamic undifferentiated cell states within the male germline. Nat Commun 9: 2819 10.1038/s41467-018-04827-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay K, Kume T, Fuchs E. 2016. FOXC1 maintains the hair follicle stem cell niche and governs stem cell quiescence to preserve long-term tissue-regenerating potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: E1506–E1515. 10.1073/pnas.1601569113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblond CP, Clermont Y. 1952. Definition of the stages of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium in the rat. Ann NY Acad Sci 55: 548–573. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1952.tb26576.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Yue L, Spradling AC. 1994. The Drosophila fusome, a germline-specific organelle, contains membrane skeletal proteins and functions in cyst formation. Development 120: 947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Celso L, Fleming HE, Wu JW, Zhao CX, Miake-Lye S, Fujisaki J, Côté D, Rowe DW, Lin CP, Scadden DT. 2009. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature 457: 92–96. 10.1038/nature07434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Garcia C, Klein AM, Simons BD, Winton DJ. 2010. Intestinal stem cell replacement follows a pattern of neutral drift. Science 330: 822–825. 10.1126/science.1196236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord T, Oatley JM. 2017. A revised Asingle model to explain stem cell dynamics in the mouse male germline. Reproduction 154: R55–R64. 10.1530/REP-17-0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord T, Oatley MJ, Oatley JM. 2018. Testicular architecture is critical for mediation of retinoic acid responsiveness by undifferentiated spermatogonial subtypes in the mouse. Stem Cell Reports 10: 538–552. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascré G, Dekoninck S, Drogat B, Youssef KK, Brohée S, Sotiropoulou PA, Simons BD, Blanpain C. 2012. Distinct contribution of stem and progenitor cells to epidermal maintenance. Nature 489: 257–262. 10.1038/nature11393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meistrich ML, van Beek ME. 1993. Spermatogonial stem cells. In Cell and molecular biology of the testis (ed. Desjardins C, Ewing LL), pp. 266–295. Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Lindahl M, Hyvönen ME, Parvinen M, de Rooij DG, Hess MW, Raatikainen-Ahokas A, Sainio K, Rauvala H, Lakso M, et al. 2000. Regulation of cell fate decision of undifferentiated spermatogonia by GDNF. Science 287: 1489–1493. 10.1126/science.287.5457.1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobasseri SA, Zijl S, Salameti V, Walko G, Stannard A, Garcia-Manyes S, Watt FM. 2019. Patterning of human epidermal stem cells on undulating elastomer substrates reflects differences in cell stiffness. Acta Biomater 87: 256–264. 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.01.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris LX, Spradling AC. 2011. Long-term live imaging provides new insight into stem cell regulation and germline-soma coordination in the Drosophila ovary. Development 138: 2207–2215. 10.1242/dev.065508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Scadden DT. 2014. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 505: 327–334. 10.1038/nature12984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. 2008. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell 132: 598–611. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa T, Omatsu Y, Sugiyama T. 2011. Control of hematopoietic stem cells by the bone marrow stromal niche: the role of reticular cells. Trends Immunol 32: 315–320. 10.1016/j.it.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Nabeshima Y, Yoshida S. 2007. Functional identification of the actual and potential stem cell compartments in mouse spermatogenesis. Dev Cell 12: 195–206. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Sharma M, Nabeshima Y, Braun RE, Yoshida S. 2010. Functional hierarchy and reversibility within the murine spermatogenic stem cell compartment. Science 328: 62–67. 10.1126/science.1182868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JO, Chen C, Yamashita YM. 2019. Germline stem cell homeostasis. Curr Top Dev Biol 135: 203–244. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakberg EF. 1956. Duration of spermatogenesis in the mouse and timing of stages of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium. Am J Anat 99: 507–516. 10.1002/aja.1000990307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakberg EF. 1971. Spermatogonial stem-cell renewal in the mouse. Anat Rec 169: 515–531. 10.1002/ar.1091690305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohbo K, Yoshida S, Ohmura M, Ohneda O, Ogawa T, Tsuchiya H, Kuwana T, Kehler J, Abe K, Schöler HR, et al. 2003. Identification and characterization of stem cells in prepubertal spermatogenesis in mice. Dev Biol 258: 209–225. 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00111-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perey B, Clermont Y, Leblond CP. 1961. The wave of the seminiferous epithelium in the rat. Dev Dyn 108: 47–77. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips BT, Gassei K, Orwig KE. 2010. Spermatogonial stem cell regulation and spermatogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365: 1663–1678. 10.1098/rstb.2010.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsma L, Ellenbroek SIJ, Zomer A, Snippert HJ, de Sauvage FJ, Simons BD, Clevers H, van Rheenen J. 2014. Intestinal crypt homeostasis revealed at single-stem-cell level by in vivo live imaging. Nature 507: 362–365. 10.1038/nature12972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rognoni E, Watt FM. 2018. Skin cell heterogeneity in development, wound healing, and cancer. Trends Cell Biol 28: 709–722. 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompolas P, Greco V. 2014. Stem cell dynamics in the hair follicle niche. Semin Cell Dev Biol 25–26: 34–42. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompolas P, Deschene ER, Zito G, Gonzalez DG, Saotome I, Haberman AM, Greco V. 2012. Live imaging of stem cell and progeny behaviour in physiological hair-follicle regeneration. Nature 487: 496–499. 10.1038/nature11218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompolas P, Mesa KR, Greco V. 2013. Spatial organization within a niche as a determinant of stem-cell fate. Nature 502: 513–518. 10.1038/nature12602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompolas P, Mesa KR, Kawaguchi K, Park S, Gonzalez D, Brown S, Boucher J, Klein AM, Greco V. 2016. Spatiotemporal coordination of stem cell commitment during epidermal homeostasis. Science 352: 1471–1474. 10.1126/science.aaf7012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell L, Ettlin R, Sinha Hikim A, Clegg E. 1990. Histological and histopathological evaluation of the testis. Cache River, Clearwater, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Sada A, Suzuki A, Suzuki H, Saga Y. 2009. The RNA-binding protein NANOS2 is required to maintain murine spermatogonial stem cells. Science 325: 1394–1398. 10.1126/science.1172645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sada A, Jacob F, Leung E, Wang S, White BS, Shalloway D, Tumbar T. 2016. Defining the cellular lineage hierarchy in the interfollicular epidermis of adult skin. Nat Cell Biol 18: 619–631. 10.1038/ncb3359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos AJM, Lo YH, Mah AT, Kuo CJ. 2018. The intestinal stem cell niche: homeostasis and adaptations. Trends Cell Biol 28: 1062–1078. 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Aiyama Y, Ishii-Inagaki M, Hara K, Tsunekawa N, Harikae K, Uemura-Kamata M, Shinomura M, Zhu XB, Maeda S, et al. 2011a. Cyclical and patch-like GDNF distribution along the basal surface of Sertoli cells in mouse and hamster testes. PLoS ONE 6: e28367 10.1371/journal.pone.0028367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Katagiri K, Gohbara A, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Ogura A, Kubota Y, Ogawa T. 2011b. In vitro production of functional sperm in cultured neonatal mouse testes. Nature 471: 504–507. 10.1038/nature09850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrans-Stassen BH, van de Kant HJ, de Rooij DG, van Pelt AM. 1999. Differential expression of c-kit in mouse undifferentiated and differentiating type A spermatogonia. Endocrinology 140: 5894–5900. 10.1210/endo.140.12.7172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Braun RE. 2018. Cyclical expression of GDNF is required for spermatogonial stem cell homeostasis. Development 145: dev151555 10.1242/dev.151555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Srivastava A, Fairfield HE, Bergstrom D, Flynn WF, Braun RE. 2019. Identification of EOMES-expressing spermatogonial stem cells and their regulation by PLZF. eLife 8: e43352 10.7554/eLife.43352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng XR, Matunis E. 2011. Live imaging of the Drosophila spermatogonial stem cell niche reveals novel mechanisms regulating germline stem cell output. Development 138: 3367–3376. 10.1242/dev.065797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng XR, Brawley CM, Matunis EL. 2009. Dedifferentiating spermatogonia outcompete somatic stem cells for niche occupancy in the Drosophila testis. Cell Stem Cell 5: 191–203. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons BD, Clevers H. 2011. Strategies for homeostatic stem cell self-renewal in adult tissues. Cell 145: 851–862. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, van der Flier LG, Sato T, van Es JH, van den Born M, Kroon-Veenboer C, Barker N, Klein AM, van Rheenen J, Simons BD, et al. 2010. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143: 134–144. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song HW, Wilkinson MF. 2014. Transcriptional control of spermatogonial maintenance and differentiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 30: 14–26. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A, Fuller MT, Braun RE, Yoshida S. 2011. Germline stem cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: a002642 10.1101/cshperspect.a002642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine RR, Matunis EL. 2013. Stem cell competition: finding balance in the niche. Trends Cell Biol 23: 357–364. 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Diaz VD, Hermann BP. 2019. What has single-cell RNA-Seq taught us about mammalian spermatogenesis? Biol Reprod 101: 617–634. 10.1093/biolre/ioz088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabib T, Morse C, Wang T, Chen W, Lafyatis R. 2018. SFRP2/DPP4 and FMO1/LSP1 define major fibroblast populations in human skin. J Invest Dermatol 138: 802–810. 10.1016/j.jid.2017.09.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takase HM, Nusse R. 2016. Paracrine Wnt/β-catenin signaling mediates proliferation of undifferentiated spermatogonia in the adult mouse testis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: E1489–E1497. 10.1073/pnas.1601461113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, Jain R, LeBoeuf MR, Wang Q, Lu MM, Epstein JA. 2011. Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science 334: 1420–1424. 10.1126/science.1213214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G, Lehrer MS, Jensen PJ, Sun TT, Lavker RM. 2000. Involvement of follicular stem cells in forming not only the follicle but also the epidermis. Cell 102: 451–461. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00050-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokue M, Ikami K, Mizuno S, Takagi C, Miyagi A, Takada R, Noda C, Kitadate Y, Hara K, Mizuguchi H, et al. 2017. SHISA6 confers resistance to differentiation-promoting wnt/β-catenin signaling in mouse spermatogenic stem cells. Stem Cell Rep 8: 561–575. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Siegenthaler JA, Dowell RD, Yi R. 2016. Foxc1 reinforces quiescence in self-renewing hair follicle stem cells. Science 351: 613–617. 10.1126/science.aad5440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt FM, Hogan BL. 2000. Out of Eden: stem cells and their niches. Science 287: 1427–1430. 10.1126/science.287.5457.1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita YM, Fuller MT, Jones DL. 2005. Signaling in stem cell niches: lessons from the Drosophila germline. J Cell Sci 118: 665–672. 10.1242/jcs.01680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S. 2012. Elucidating the identity and behavior of spermatogenic stem cells in the mouse testis. Reproduction 144: 293–302. 10.1530/REP-11-0320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S. 2016. From cyst to tubule: innovations in vertebrate spermatogenesis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 5: 119–131. 10.1002/wdev.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S. 2018a. Open niche regulation of mouse spermatogenic stem cells. Dev Growth Differ 60: 542–552. 10.1111/dgd.12574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S. 2018b. Regulatory mechanism of spermatogenic stem cells in mice: their dynamic and context-dependent behavior. In Reproductive & developmental strategies (ed. Kobayashi K, Kitano T, Iwao Y, Kondo M), pp. 47–67. Springer, Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S. 2019. Heterogeneous, dynamic, and stochastic nature of mammalian spermatogenic stem cells. Curr Top Dev Biol 135: 245–285. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2019.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Takakura A, Ohbo K, Abe K, Wakabayashi J, Yamamoto M, Suda T, Nabeshima Y. 2004. Neurogenin3 delineates the earliest stages of spermatogenesis in the mouse testis. Dev Biol 269: 447–458. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Nabeshima Y, Nakagawa T. 2007a. Stem cell heterogeneity: actual and potential stem cell compartments in mouse spermatogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1120: 47–58. 10.1196/annals.1411.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Sukeno M, Nabeshima Y. 2007b. A vasculature-associated niche for undifferentiated spermatogonia in the mouse testis. Science 317: 1722–1726. 10.1126/science.1144885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]