To the Editor:As of July 24, 2020, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has caused over 15,000,000 confirmed cases and over 600,000 deaths globally (1). Risk factors for severe illness, such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, have been described (2). According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), individuals with asthma are also at higher risk for hospitalization and other severe outcomes from COVID-19 (3); however, the low numbers of individuals with asthma among hospitalized patients across many available international studies challenges this assumption. In this study, we compared the asthma prevalence among patients hospitalized for COVID-19 reported in 15 studies to that of the corresponding population’s asthma prevalence and to the 4-year average asthma prevalence in influenza hospitalizations in the United States. Furthermore, using a cross-sectional analysis of 436 patients with COVID-19 admitted to the University of Colorado Hospital, we evaluated the likelihood of intubation in patients with asthma compared with patients without asthma.

Methods and Results

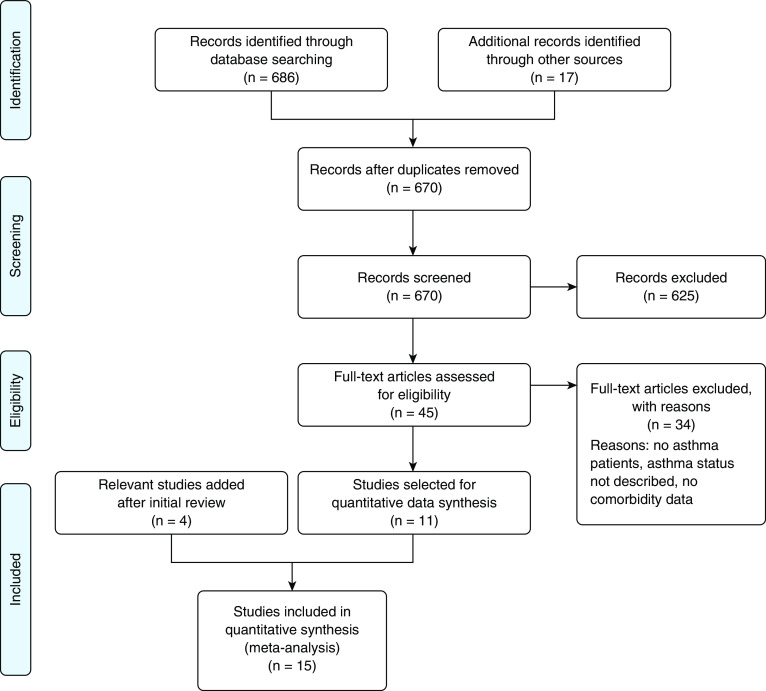

We performed a focused literature review of the English literature to identify studies reporting asthma prevalence among patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection and published before May 7, 2020, identified in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, Medline, and the CDC’s Mortality Morbidity Weekly Review. Unpublished literature was not considered. Review included studies published in English that reported COVID-19 hospitalizations together with asthma or chronic respiratory disease prevalence (not chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] alone). Three independent reviewers agreed on 11 studies to be included initially; an additional four studies were subsequently included after the review dates mentioned above. (Figure 1). The search criteria identified 686 unique studies. Duplicates were removed, leaving 670 unique articles. After the above criteria were applied, 45 articles were assessed with full-text review. Finally, 15 studies were included in our analysis. We used the Clopper-Pearson method to create 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for asthma prevalence within each study (Figure 1). In addition, using local data from patients in our hospital (Table 1), we performed a multivariable logistic-regression model using multiple imputation to determine the effect of asthma status on intubation status after controlling for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) diagram detailing focused review of the literature and excluded studies. The initial number of studies identified after focused review was 11. An additional four studies were added after initial review.

Table 1.

Sample population characteristics of patients with and without asthma among COVID-19–related admissions at University of Colorado

| No Asthma (N = 383; 88%) | Asthma (N = 53; 12%) | Total (N = 436) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (N = 435) | 0.209 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 55.1 (16.7) | 52.0 (18.1) | 54.7 (16.9) | |

| Range | 19–100 | 21–92 | 19–100 | |

| Sex (N = 434), n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| Male | 221 (57.9) | 18 (34.6) | 239 (55.1) | |

| Female | 161 (42.1) | 34 (65.4) | 195 (44.9) | |

| BMI (N = 351) | <0.001 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 30.8 (7.2) | 35.7 (12.3) | 31.4 (8.2) | |

| Range | 15.0–66.2 | 17.8–82.7 | 15.0–82.7 | |

| Intubation status (N = 338), n (%) | 0.461 | |||

| No | 196 (66.4) | 31 (72.1) | 227 (67.2) | |

| Yes | 99 (33.6%) | 12 (27.9%) | 111 (32.8%) | |

| Sent to ICU (N = 351), n (%) | 0.424 | |||

| No | 183 (59.6) | 29 (65.9) | 212 (60.4) | |

| Yes | 124 (40.4) | 15 (34.1) | 139 (39.6) |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ICU = intensive care unit; SD = standard deviation.

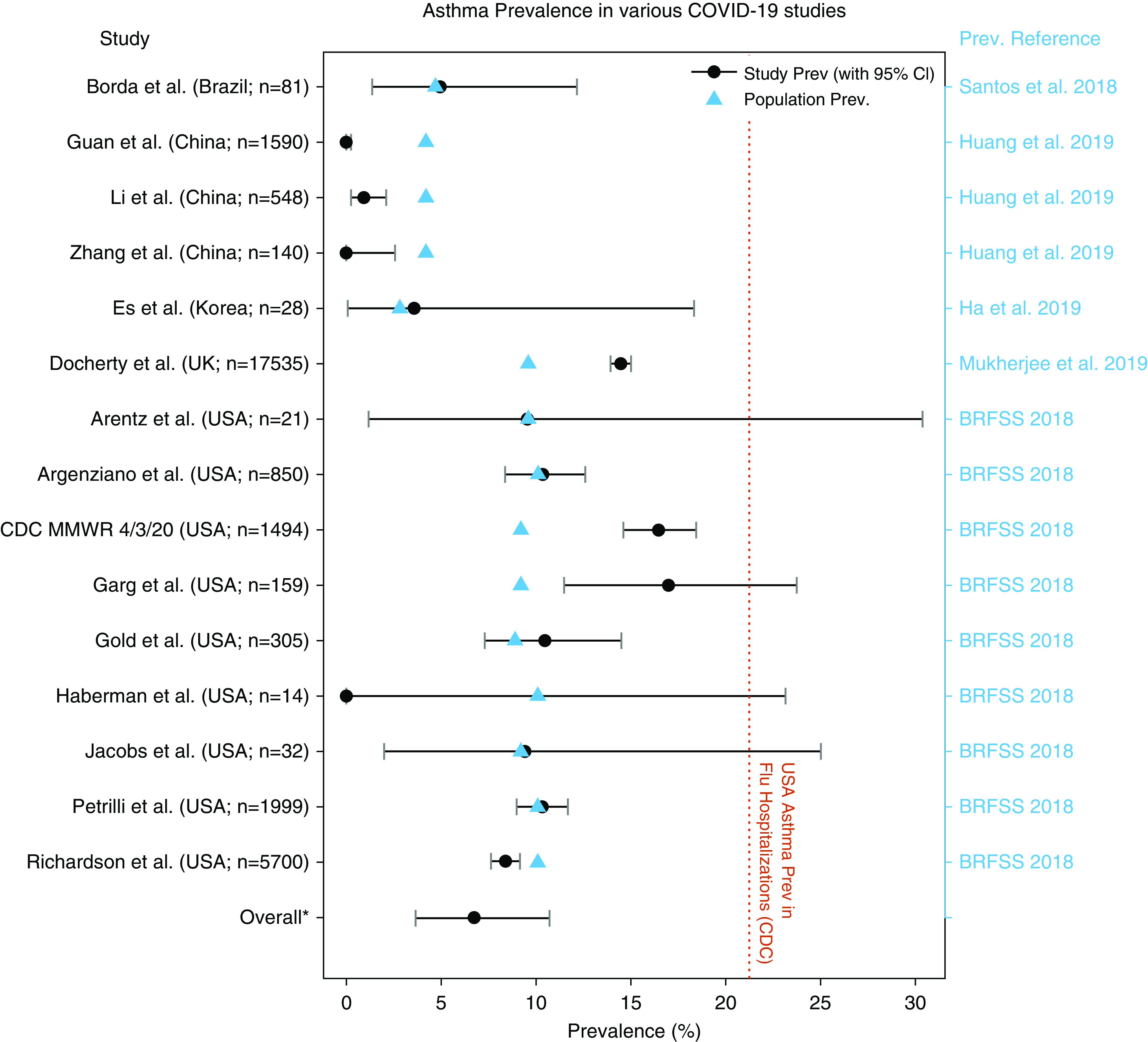

On the basis of Figure 2, the proportion of patients with asthma among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 is relatively similar to that of each study site’s population asthma prevalence. This finding is in stark contrast to findings regarding influenza, in which individuals with asthma make up more than 20% of those hospitalized in the United States. Using data from our hospital, we observed that among patients with COVID-19, those with asthma (12% prevalence), identified using the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases, 10 Revision, code J45, do not seem to be more likely than those without asthma to be intubated (odds ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.33–1.45), after adjusting for age, sex, and BMI.

Figure 2.

Comparing the prevalence (Prev.) of asthma in a series of COVID-19 studies compared with population-level Prev. The orange line corresponds to the 4-year average U.S. asthma Prev. among those hospitalized with flu (CDC FluView Data) (7). For a full study list, please see the References. *Overall (or “pooled”) Prev. (6.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.7–10.7%) and the associated CI assume random study-level effects. BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; flu = influenza; MMWR = Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that asthma prevalence among those hospitalized with COVID-19 appears to be similar to population asthma prevalence and significantly lower than asthma prevalence among patients hospitalized for influenza. Asthma also does not appear to be an independent risk factor for intubation among hospitalized patients with COVID-19, even after adjusting for BMI and age, which are well-known risk factors for severity.

Seasonal coronaviruses typically do not contribute significantly to hospitalizations due to asthma exacerbations because they primarily cause upper respiratory infections (4). In the case of SARS-CoV (not the virus causing COVID-19), individuals with asthma did not seem to be disproportionately affected, although minimal data are available to make this comparison (5, 6). In Middle East respiratory syndrome, asthma patients may be at higher risk, although data are again sparse (5).

During the 2019–2020 influenza season, 24.1% of people hospitalized with influenza had asthma, which is slightly higher than the 4-year 21% average from 2016 to 2020; however, this is considerably higher than the pooled prevalence estimate across the 15 COVID-19 studies (6.8%; 95% CI, 3.7–10.7%) shown in Figure 2 (7). Despite early concern about disproportionately high morbidity and mortality for those with asthma (8), data presented here and elsewhere show minimal evidence of a clinically significant relationship (9, 10).

Data from our hospital does not show a significant association between asthma diagnosis and greater intubation odds among patients with COVID-19, even after adjusting for BMI and age, which are well-known risk factors for severity, and were significantly associated with intubation in our model.

One possible explanation as to why COVID-19 is not associated with greater hospitalization rates among individuals with asthma may depend on the distribution of the angiotesin Converting enzyme receptor (ACE2) in the respiratory airway epithelium. It has been suggested that diabetes mellitus and hypertension may increase ACE2 expression, whereas inhaled-corticosteroid use may decrease ACE2 expression, hence leading to more difficulty with viral entry (11, 12). In addition, patients with asthma in general, and particularly those with a predominantly allergic phenotype, may have significantly lower expression of ACE2 (12). Although the degree of ACE2 receptor expression to overall COVID-19 susceptibility and disease severity is still unclear, it is certainly worth further investigation. Unfortunately, we do not have inhaled-corticosteroid data available on patients in our review or in our hospital to further elucidate possible benefit of these medications as has been suggested (13). In contrast to having asthma, having COPD increases the risk for severe COVID-19 among hospitalized patients (14). This comorbidity is associated with increased ACE2 expression in the lung tissue and small airways (15).

Given the variable prevalence of asthma among hospitalized COVID-19 populations across these studies, it is possible that reporting of comorbidities was done inconsistently across different studies, particularly because the authors did not describe how asthma or chronic respiratory disease diagnoses were gathered in each of these studies. Like studies of asthma, studies of COPD have reported prevalence rates that are lower than the population average, and this is in contrast to the higher-than-expected rates of hypertension and diabetes mellitus among hospitalized patients, which are comorbidities known to be associated with severe COVID-19.

Finally, we acknowledge that our findings may result from an insufficient sample size, and more data obtained from investigating asthma and intubation risk would be beneficial.

Although there is variable asthma prevalence among published studies of COVID-19, the prevalence appears to be similar to the population prevalence and is certainly much lower than what would be expected during seasonal influenza. The results of this study suggest that asthma does not appear to be a significant risk factor for developing severe COVID-19 requiring hospitalization or intubation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This letter has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2020. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center: COVID-19 United States cases by county. [accessed 2020 May 15]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York city area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): people with moderate to severe asthma. [accessed 2020 May 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/asthma.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jartti T, Bønnelykke K, Elenius V, Feleszko W. Role of viruses in asthma. Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42:61–74. doi: 10.1007/s00281-020-00781-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin Y, Wunderink RG. MERS, SARS and other coronaviruses as causes of pneumonia. Respirology. 2018;23:130–137. doi: 10.1111/resp.13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau AC-W, So LK-Y, Miu FP-L, Yung RW, Poon E, Cheung TM, et al. Outcome of coronavirus-associated severe acute respiratory syndrome using a standard treatment protocol. Respirology. 2004;9:173–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. FluView interactive: laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations. [accessed 2020 May 7]. Available from: https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/fluview/FluHospChars.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston SL. Asthma and COVID-19: is asthma a risk factor for severe outcomes? Allergy. 2020;75:1543–1545. doi: 10.1111/all.14348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Razzaghi H, Wang Y, Lu H, Marshall KE, Dowling NF, Paz-Bailey G, et al. Estimated county-level prevalence of selected underlying medical conditions associated with increased risk for severe COVID-19 illness: United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:945–950. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6929a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Z, Hasegawa K, Ma B, Fujiogi M, Camargo CA, Liang L. Association of asthma and its genetic predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:327–329, e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters MC, Sajuthi S, Deford P, Christenson S, Rios CL, Montgomery MT, et al. COVID-19-related genes in sputum cells in asthma: relationship to demographic features and corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:83–90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0821OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson DJ, Busse WW, Bacharier LB, Kattan M, O’Connor GT, Wood RA, et al. Association of respiratory allergy, asthma, and expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:203–206, e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halpin DMG, Faner R, Sibila O, Badia JR, Agusti A. Do chronic respiratory diseases or their treatment affect the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:436–438. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30167-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan W-J, Liang W-H, Zhao Y, Liang HR, Chen ZS, Li YM, et al. China Medical Treatment Expert Group for COVID-19. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000547. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung JM, Yang CX, Tam A, Shaipanich T, Hackett TL, Singhera GK, et al. ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000688. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00688-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.