Abstract

The first complete chloroplast genome of Amomum villosum (Zingiberaceae) was reported in this study. The A. villosum genome was 163,608 bp in length, and comprised a pair of inverted repeat (IR) regions of 29,820 bp each, a large single-copy (LSC) region of 88,680 bp, and a small single-copy (SSC) region of 15,288 bp. It encoded 141 genes, including 87 protein-coding genes (79 PCG species), 46 tRNA genes (28 tRNA species), and 8 rRNA genes (4 rRNA species). The overall AT content was 63.92%. Phylogenetic analysis showed that A. villosum was closely related to two species Amomum kravanh and Amomum compactum within the genus Amomum in family Zingiberaceae.

Keywords: Amomum villosum, Zingiberaceae, Amomum, chloroplast genome, phylogenetic analysis

Amomum villosum is one species of the genus Amomum (Zingiberaceae), which distributes predominantly in Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi and Yunan provinces in China (Wu and Larsen 2000). Amomum villosum plants are 1–3 m tall; rhizomes procumbent above ground, clothed with brown, scalelike sheaths; leaves sessile or subsessile; leaf sheath with netlike, depressed squares (Wu and Larsen 2000). Fruits of this species own high medicinal value (Wu et al. 2016). Morphological classification of Amomum species is difficult owing to the morphological similarity of vegetative parts among species in genus Amomum (Wu and Larsen 2000). Within genus Amomum, only two complete chloroplast genomes for species Amomum kravanh and Amomum compactum have been reported so far (Wu et al. 2017), hindering molecular species identification of Amomum species based on chloroplast genomes. Nevertheless, no complete chloroplast genome of A. villosum has been reported.

Amomum villosum was collected from Banna, Yunnan province, and stored at the resource garden of environmental horticulture research institute (specimen accession no. Av2015), Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guangzhou, China. Total chloroplast DNA was extracted from about 100 g of fresh leaves of A. villosum using the sucrose gradient centrifugation method (Li et al. 2012). Chloroplast DNA (accession no. AvDNA2017) was stored at −80 °C in Guangdong Key Lab of Ornamental Plant Germplasm Innovation and Utilization, Environmental Horticulture Research Institute, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guangzhou, China. Library construction was done using Illumina (Illumina, CA, USA) and PacBio (Novogene, Beijing, China) sequencing, respectively. The Illumina and PacBio sequencing data were deposited in the NCBI sequence read archive under accession numbers SRR8185318 and SRR8184508, respectively. After trimming, 80.8 M clean data of 150 bp paired-end reads and 0.48 M clean data of 8–10 kb subreads were generated. The chloroplast genome of A. villosum was assembled and annotated by using the reported methods (Li, Wu, et al. 2019). The annotated complete chloroplast genome sequence of A. villosum was submitted to the GenBank (accession no. MK262730).

The complete chloroplast genome of A. villosum was 163,608 bp in length, and comprised a pair of inverted repeat (IR) regions of 29,820 bp each, a large single-copy (LSC) region of 88,680 bp and a small single-copy (SSC) region of 15,288 bp. It was predicted to contain a total of 141 genes, including 87 protein-coding genes (79 PCG species), 46 tRNA (28 tRNA species), and 8 rRNA (4 rRNA species). Twenty species genes occurred in double copies, including eight PCG species (ndhB, rpl2, rpl23, rps7, rps12, rps19, ycf1, and ycf2), eight tRNA species (trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU, trnL-CAA, trnV-GAC, trnL-GAU, trnA-UGC, trnR-ACG, and trnN-GUU) and all four rRNA species (rrn4.5, rrn5, rrn16, and rrn23). All these 20 species genes were located in the IR regions. The ycf1 gene crossed the bounders of SSC-IRa and SSC-IRb regions, respectively, while the rps12 gene was located its first exon in the LSC region and other two exons in the IRs regions. In addition, 10 PCG genes (atpF, ndhA, ndhB, rpoC1, petB, petD, rpl2, rpl16, rps12, and rps16) and 6 tRNA genes (trnK-UUU, trnG-GCC, trnL-UAA, trnV-UAC, trnI-GAU, and trnA-UGC) had a single intron, while two other genes (ycf3 and clpP) possessed two introns. The nucleotide composition was asymmetric (31.68% A, 18.30% C, 17.78% G, 32.25% T) with an overall AT content of 63.92%. The AT contents of the LSC, SSC, and IR regions were 66.30%, 69.94%, and 58.85%, respectively.

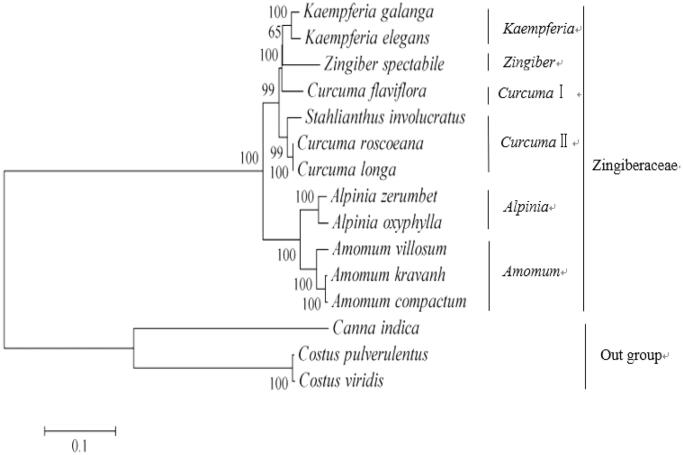

To obtain its phylogenetic position within family Zingiberaceae, a phylogenetic tree was constructed by using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) arrays from available 15 species chloroplast genomes using Costus viridis, Costus pulverulentus, and Canna indica as outgroup taxa. The SNP arrays were obtained as a previously described method (Li, Zhao, et al. 2019). For each chloroplast genome, all SNPs were connected in the same order to obtain a sequence in FASTA format. Multiple FASTA format sequences alignments were carried out using ClustalX version 1.81 (Thompson et al. 1997). A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree (Figure 1) was constructed using the SNPs from 15 chloroplast genomes alignment result with MEGA7 (Kumar et al. 2016). As shown in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1), A. villosum was closely related to two species A. kravanh and A. compactum within the genus Amomum in family Zingiberaceae with available SNPs.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree constructed with single nucleotide polymorphisms arrays from 15 species chloroplast genomes using maximum-likelihood method. The bootstrap values were based on 1000 replicates and are indicated next to the branches. Accession numbers: Alpinia zerumbet JX088668, Alpinia oxyphylla NC_035895.1, Curcuma flaviflora KR967361, Curcuma roscoeana NC_022928.1, Curcuma longa MK262732, Kaempferia galanga MK209001, Kaempferia elegans MK209002, Zingiber spectabile JX088661, Amomum kravanh NC_036935.1, Amomum compactum NC_036992.1, Stahlianthus involucratus MK262725, Costus pulverulentus KF601573, Costus viridis MK262733, and Canna indica KF601570.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 33:1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DM, Wu W, Liu XF, Zhao CY. 2019. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the complete chloroplast genome sequence of Costus viridis (Costaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4:1118–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DM, Zhao CY, Liu XF. 2019. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Kaempferia galanga and Kaempferia elegans: molecular structures and comparative analysis. Molecules. 24:474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Hu Z, Lin X, Li Q, Gao H, Luo G, Chen S. 2012. High-throughput pyrosequencing of the complete chloroplast genome of Magnolia officinalis and its application in species identification. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 47:124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Larsen K. 2000. Zingiberaceae vol 24. Flora of China. Beijing (China): Science Press; p. 322–377. [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Liu N, Ye Y. 2016. The Zingiberaceous resources in China. Wuhan (China): Huazhong university of science and technology university press; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Li Q, Hu Z, Li X, Chen S. 2017. The complete Amomum kravanh chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the commelinids. Molecules. 22:1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]