As a medical student, and thereafter as a psychiatry resident, I (J.L.) spent more than 10 years studying diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders. After several years of clinical experience, I thought I had gained some insight into what mental suffering is about. However, as I found out, nothing out there can prepare you for what it is really like.

Here, I describe my journey toward finding meaning in depression, and how low mood becomes a psychotic prism through which the world is observed—my life the last few years.

In the spring of 2017, my life took an unexpected turn as I suddenly found myself in the other chair: a patient instead of a student in psychiatry. The year before that, I had been using bupropion, an antidepressant, to help me with attention deficit and improving structure in everyday life. At that time, I was working in an outpatient clinic for mood disorders, treating patients, and prescribing medications if necessary. I was therefore quick to recognize side effects, like muscle tension and cramps in my jaw and upper legs, associated with my own treatment. Together with my psychiatrist, we decided to discontinue the bupropion, as I was doing well. With the wisdom of hindsight, we should perhaps have considered a risk, given a personal history of depression, a family history of mood disorders, and a particularly busy period at work. In the first weeks after stopping, no problems arose. The muscle cramps disappeared and I was relieved not to have to take medication every day.

However, after a while I began feeling tired, had trouble concentrating, and found it increasingly difficult to get up in the morning. At some point, I decided to use light therapy for 20 min each morning, hoping it would help me get out and about more easily. It did not work. Sleeping, getting started in the morning, and staying motivated throughout the day was not self-evident anymore, but increasingly felt as hard labor. Nightmares started to occur that left me drained of energy during the day. I also felt less confident at work. Internal struggles arose because I was feeling down and it seemed inappropriate that I would be helping others while secretly struggling myself. I increasingly felt like an impostor who could be exposed at any moment. Kind words of others did nothing to change this belief. People around me started noticing changes and finally my colleagues gently but clearly indicated I should seek help. In April 2017, I called in sick and visited my psychiatrist. He confirmed a major depression and together we started to look for new treatment options.

A difficult period started during which I felt utterly lost. I do not remember much from the first weeks, as everything was blurred. My thoughts and movements went as if in slow motion. I could not enjoy even the smallest things and suddenly my future perspective was gone. I experienced psychosis—perceiving a world that was bleak, threatening, lonely, and devoid of meaning. Colors seemed to disappear and I felt that I did not belong to this world anymore, as if there was an invisible shield between me and other people. Yet, this shocking observation left me completely indifferent. During the night, I was living in a horror movie, stuck in vivid nightmares that made me want to avoid sleep. This sleep deprivation only added to the misery, pulling me into its psychotic realm where the line between what is real and what is not starts to disappear.

The part of my psychiatry training that—fortunately—continued was the compulsory trajectory of personal psychotherapy. I was also prescribed antidepressants. One evening, when I felt a little better and found myself able to take a degree of perspective, I wondered if I could monitor the lived experience of my suffering, making it somehow part of my training and my desire to have a future as a psychiatrist. As my concentration was at a low point, I required a relatively simple way to document my journey.

I send an e-mail with a query to a professor I knew. Although I felt embarrassed immediately afterwards, his reaction was supportive, saying my story was important. It made me feel validated and even generated a tiny bit of confidence. He suggested monitoring the recovery process by using the Experience Sampling Method in the form of a freeware smartphone application called the PsyMate. Experience sampling is a self-monitoring tool for momentary data collection, capturing the evolution of mood, cognition, and behavior over time. The person is required to complete multiple short questionnaires of 1-min duration at several moments per day, in response to auditory signals. These data can then be displayed in graphs and figures, making patterns in daily life visible. Experience sampling is used in research and has relevance for clinical practice. Often, for short sampling periods of 1 week. In the past, I had used the PsyMate during a research internship. Back then, it had no personal significance and soon the routine became annoying. Not so, it turned out, when I was ill.

Together with an ESM expert, I began the process that eventually would result in over 2 years of data collection. The app consists of a standard set of questions, monitoring mood (eg, “I feel anxious”), current context (eg, “what am I doing right now”), and appraisal of context (eg, “I like this company”) at 10 random moments per day. In addition to these assessments, a morning and evening questionnaire are available to capture sleep quality and overall feelings at the end of the day. This was our starting point. Every week, we sat together to look at my results on the PsyMate website (www.psymate.eu). In the beginning, this process of weekly contact and daily monitoring, thereby contributing to research, provided an anchor of meaning and purpose.

Over the following weeks, we personalized items to include other relevant symptoms and experiences. For example, we added “I feel numbed,” an overwhelming feeling at the time. Important was that we made sure the list remained balanced and contained positive items as well, to prevent a negative influence on my mood. We also decided to monitor medication more closely by adding a category to the question “Since the last beep I used….” In addition, we added an item about meditation, because we were wondering if the classes I started would impact my mood. Not everything could be personalized; beeps were programmed between 8.30 am and 10.30 pm, which frequently resulted in missed beeps in the morning.

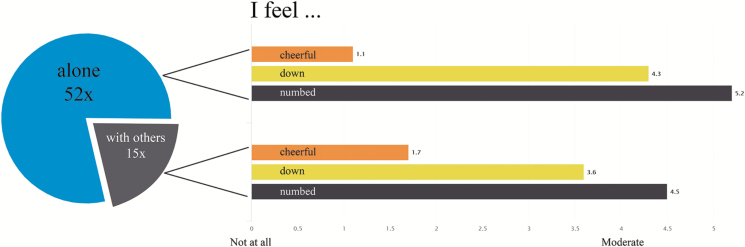

As the collected data were growing, multiple interesting patterns became visible. Often, we would see changes, which made me conscious of minor shifts that I could not have consciously formulated in advance, but which I then recognized were present. In the beginning, few fluctuations were apparent in my mood and I was feeling down all the time. After some time, my treatment started to have effect and more reactivity became visible during the day. Antidepressants often take some time before taking effect, which was also reflected in the data. PsyMate became a way to help me assess treatment effects and propose changes. Examining time budgets was also helpful and a little confronting at first. I was spending a lot of time at home and by myself, although we learned, by graphically combining mood with activities or company, that being outdoors and with others resulted in an increase in positive feelings (figure 1).

Fig. 1.

The pie chart (left) displays my answers on the question “Who am I with” during 2 weeks of sampling, indicating that I was alone 52 times and with others 15 times. The bar graph (right) shows how cheerful, down, and numbed I felt when I was alone vs when I was with others. I felt more cheerful, less down, and less numb when with others.

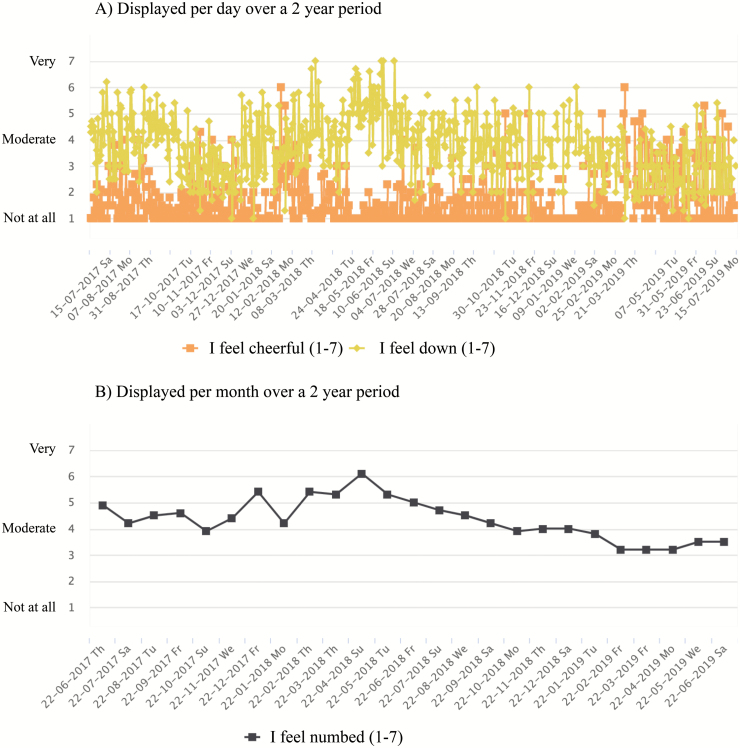

There were many incredibly discouraging drawbacks in my recovery process. However, because I kept monitoring my mood, we could always inspect the “bigger picture” showing overall slow progress over the momentary hollows. This helped me realize I was still moving forward, even though it sometimes did not feel remotely as if my mental state had improved (figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Online feedback graph showing my experience sampling data over a period of 2 years. Part (A) displays the mood items cheerful and down over time with answers averaged by day. Fluctuations in my mood can be seen, next to how the feelings relate to each other. Part (B) displays the item numbed over time with answers averaged by month. A general decline can be seen in how numb I felt, showing my overall recovery.

After 2 grueling years, I am doing better now. I no longer feel an imposter, disconnected from the world. Indeed, monitoring helped me to appraise my situation objectively and kept me on top of my depression instead of being lived by it. Recently, I restarted my psychiatry residency training. Having experienced the benefits of monitoring during different stages of recovery, I would definitely encourage others to integrate such tools into their therapy. Early on, it provides an easy way to keep track of what is going on without having to think too much. Later on, it provides concrete clues for change, guiding treatment choices. At the end, it displays a story about you, as a person, with all the thousands of literally ups and downs as a lived reality. In a strange way, it is both comforting and aiding in a sense of control that one can never completely disappear into the darkness. Having constructed the journey of my lived experience, I am confident that I will be a better doctor. It gives me courage to share my story and inspire healthcare professionals to do the same.

Closing perspective—I (S.J.W.V.) feel privileged to have been able to reflect on the experiences collected by Jaimie. Working together on personalizing PsyMate and finding meaning in a challenging period of life has been a valuable and special experience. As a researcher and psychologist, I learned what is important in experience sampling and what is less relevant. The key is to attempt to reduce complexity to simplicity. Pervasive patterns, once discovered, are turning points in guiding change or finding understanding. I am proud of Jaimie, it takes courage and endurance to open up and use one’s own experience and share it for the benefit of others.