Abstract

In the present study, the complete chloroplast genome of Vitis davidii Foex strain ‘SJTU003’ was assembled and subjected to phylogenetic analysis. This chloroplast genome of ‘SJTU003’ was 161,335 bp in length, including two inverted repeat regions (IRa and IRb) that were separated by a large single-copy region (89,570 bp) and a small single-copy region (19,059 bp). The genome contained 133 genes, including 88 protein-coding genes, 37 tRNA genes, and 8 rRNA genes. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that V. davidii is most closely related to Vitis flexuosa and Vitis amurensis.

Keywords: Vitis davidii Foex, Illumina sequencing, chloroplast genome, phylogenetic analysis

Vitis davidii Foex, which is one of the native wild grape species found in south central China, has the potential to be used for making wine and juice (Yi et al. 2019). To make better use of V. davidii, the complete chloroplast genome of V. davidii strain ‘SJTU003’ was assembled (GenBank: MN181471) and subjected to phylogenetic analysis.

Fresh ‘SJTU003’ leaves were sampled from the Research Vineyard of Grape Germplasm and Breeding at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 800 Dongchuan Road, Minhang District, Shanghai, China (121°26′E; 31°02′N), and total genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method (Fu et al. 2019). The DNA was stored at −80 °C at the Center of Viticulture and Enology of Shanghai Jiao Tong University and then sequenced using the HiSeq X pair-end 150 sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). A total of 3.79 Gb clean data were obtained, and chloroplast genome was assembled using SOAPdenovo v2.04 (Luo et al. 2012) with the chloroplast genome sequence of Vitis vinifera (DQ424856) as a reference. The DOGMA package (Wyman et al. 2004) and BLAST 2.6.0+ (ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/) were used to predict and annotate genes, respectively.

This chloroplast genome of ‘SJTU003’ was 161,335 bp in length, including two inverted repeat (IR) regions (IRa and IRb) that were separated by a large single-copy (LSC) region (89,570 bp) and a small single-copy (SSC) region (19,059 bp). The GC content of the genome was 37.4%, whereas that of the LSC and SSC regions were 35 and 32% in SSC, and that of the IR regions was 43%. The genome contained 133 genes, including 88 protein-coding genes, 37 tRNA genes, and 8 rRNA genes. Among these genes, 19 contained one intron (tRNA-Lys, rps16, tRNA-Gly, atpF, rpoC1, tRNA-Leu, tRNA-Val, petB, petD, rpl16, two rpl2, two ndhB, two tRNA-Ile, two tRNA-Ala, and ndhA), and 4 contained two introns (ycf3, clpP, and two rps12).

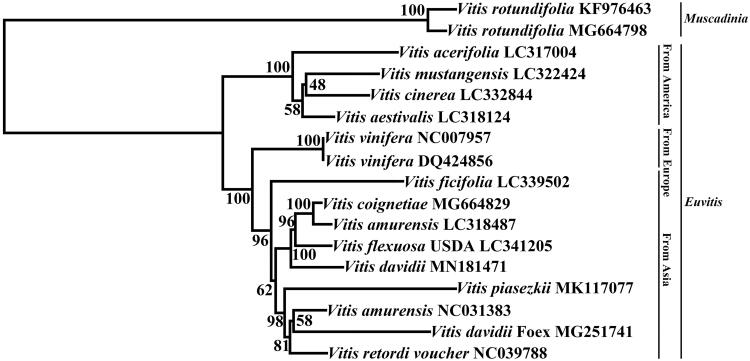

To investigate the phylogenetic position of V. davidii within the Vitaceae, the chloroplast genome sequence of ‘SJTU003’ and those of 16 other Vitis species were aligned using MAFFT version 7 (Katoh and Standley 2013). A neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA X (Kumar et al. 2018; Figure 1). The phylogenetic position of different V. davidii Foex strains had diversity, and V. davidii was most closely related to Vitis flexuosa and Vitis amurensis.

Figure 1.

The phylogenetic relationship of 17 species within the Vitis species based on neighbour-joining (NJ) analysis of chloroplast genomes. The bootstrap values are based on 1000 replicates and are shown next to the nodes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Fu P, Tian Q, Li R, Wu W, Song S, Lu J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Vitis piasezkii. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):1034–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30(4):772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 35(6): 1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J, He G, Chen Y, Pan Q, Liu Y, et al. 2012. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience. 1(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. 2004. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 20(17):3252–3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi T, Hong Y, Li M, Li X. 2019. Examination and characterization of key factors to seasonal epidemics of downy mildew in native grape species Vitis davidii in southern China with the use of disease warning systems. Eur J Plant Pathol. 154(2):389–404. [Google Scholar]