Abstract

Background:

The Strategies to Reduce Injuries and Develop Confidence in Elders (STRIDE) Study is testing the effectiveness of a multifactorial intervention to prevent serious fall injuries.

Objectives:

To describe procedures that were implemented to optimize participant retention; report retention yields by age, sex, clinical site, and follow-up time; provide reasons for study withdrawals; and highlight the successes and lessons learned from the STRIDE retention efforts.

Design:

Pragmatic cluster randomized trial.

Setting:

86 primary care practices within 10 US health care systems.

Participants:

5,451 community-living persons, 70+ years, at high risk for serious fall injuries.

Measurements:

Study outcomes were collected every 4 months by a central call center. Reconsent was required to extend follow-up beyond the originally planned 36 months.

Results:

Over a median [IQR] follow-up of 3.2 [2.8–3.7] years, 439 (8.1%) participants died and 600 (11.0%) withdrew their consent or did not reconsent to extend follow-up beyond 36 months, yielding rates (per 100 person-years) of deaths and withdrawals of 2.6 and 3.6. The withdrawal rate increased with advancing age, was comparable for men and women, and did not differ much by clinical site. The most common reasons for withdrawal were illness and unable to contact for reconsent at 36 months. Completion of the follow-up interviews was greater than 93% at each time point. Most participants completed all (71.8%) or all but one (9.2%) of the follow-up interviews. The most common reason for not completing a follow-up interview was unable to contact, with rates ranging from 2.8% at 40 months to 4.6% at 20 months.

Conclusions:

Completion of the thrice-yearly follow-up interviews in STRIDE was high, and retention of participants over 44 months exceeded the original projections. The procedures used in STRIDE, together with lessons learned, should assist other investigators who are planning or conducting large pragmatic trials of vulnerable older persons.

Keywords: older persons, retention, pragmatic trials

Retention of participants in clinical trials is important for ensuring that the results are adequately powered, valid and generalizable.1–3 A trial with higher than expected losses to follow up might be under-powered to detect a treatment effect even if its recruitment target was met.1 In addition, poor retention of participants can reduce the internal validity of a trial when losses to follow-up differ significantly by treatment group.2 Finally, because participants who drop out of a study usually differ from those who are retained,3 findings from a trial may not be generalizable to the target population when retention is poor.

Nonetheless, strategies to optimize retention in clinical trials have generally received less attention than those focused on recruitment. Even reports about recruitment and retention have focused considerably more attention on the former issue than the latter.4–7 Relatively few prior trials have focused on strategies to enhance retention of older persons who are frail or at risk of falls.8 Retention is more challenging in this population because of the high prevalence of impairments in mobility, cognition, hearing, and vision, and because concurrent health problems often worsen over time, leading to hospitalization and subsequent changes in living situation.

We recently completed follow-up for the Strategies to Reduce Injuries and Develop Confidence in Elders (STRIDE) Study, a large 44-month pragmatic cluster randomized trial.9 The aim of STRIDE is to determine the effectiveness of an evidence-based, patient-centered multifactorial intervention to prevent serious fall injuries. The current report describes the procedures that allowed us to optimize retention over a follow-up period ranging from 24 to 44 months. We report retention yields by age, sex, clinical site, and follow-up time, provide reasons for study withdrawals, and highlight the successes and lessons learned from the STRIDE retention efforts.

METHODS

Overview

The study design, screening, recruitment and baseline characteristics for STRIDE have been previously described.9, 10 Over the course of 20 months, 5,451 community-living persons, 70 years or older, who were at high risk for serious fall injuries, were recruited from 86 primary care practices within 10 diverse healthcare systems (i.e. clinical sites) across the US.10 Recruitment, enrollment, and follow-up assessments were completed over the phone by the Yale Recruitment and Assessment Center (RAC). All study materials and interviews were available in English and Spanish. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Data on falls, serious fall injuries, and other fall injuries were collected every 4 months using a structured telephone interview that also ascertained hospital admissions, emergency department (ED) visits, and other health care utilization. To facilitate recall, participants were provided monthly calendars to record their falls and injuries. Details about the ascertainment and adjudication of serious fall injuries are provided elsewhere.11 Among a random subsample of 714 participants, who were enrolled earlier in the trial before the age criterion was lowered from 75 to 70 years,10 information was also collected at baseline, 12 months and 24 months on a set of secondary well-being outcomes,9 including concern about falling,12 anxiety and depressive symptoms,13 and physical function and disability.14 The original sample size estimates assumed 3% annual loss-to-follow-up in the absence of a serious fall injury or death and 7% annual death rate in the absence of a serious fall injury.9

Study procedures were developed in partnership with a diverse set of patient stakeholders,9 who also reviewed relevant materials, such as participant letters, interviewer scripts, brochures and newsletters, to ensure clarity and readability. To preserve blinding of RAC interviewers, communication with the clinical sites was conducted by unblinded RAC staff in partnership with Central Project Management (CPM), located at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Finally, detailed progress reports were reviewed during monthly conference calls by the Screening, Recruitment and Retention Committee, which included representatives from the clinical sites, patient stakeholders, RAC, Data Coordinating Center (DCC), and CPM.

Extension of Follow-up

Follow-up was originally planned for up to 36 months, but after approval had been obtained from the Central Institutional Review Board (IRB) it was later extended to March 2019 (to maintain 90% power),10 providing 24 to 44 months of surveillance. Reconsent to extend follow-up was requested from participants at the end of the 36-month telephone interview.

Procedures to Optimize Retention

Time of Enrollment

During the informed consent process, the purpose of the trial, study requirements, and time commitment were clearly explained to the participant and/or surrogate. Contact information was obtained for the participant, surrogate, and up to two other persons who did not live with the participant but would know how to reach them if RAC staff were unsuccessful.

Mailed Correspondence

After enrollment, a packet of materials was mailed to participants by unblinded RAC staff, including: thank you letter; study brochure; privacy and consent information sheet; study assignment (intervention or usual care); initial fall calendars (5 months) with instructions to complete each month; STRIDE magnet with recommendation to post with calendars on the refrigerator; and NIA “Falls and Older Adults” sheet (Supplementary Document S1). In addition, the usual care group received the CDC Stay Independent brochure (www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/stay_independent_brochure-print.pdf).

About two weeks prior to each thrice-yearly interview, a follow-up packet was mailed, including: cover letter that provided a reminder of the upcoming call, expressed appreciation, and encouraged continued participation in the study; and a set of 5 monthly fall calendars. These mailings also included a token of appreciation every 12 months, including a magnifier, eyeglass cleaning cloth, and rubber jar opener, each branded with the STRIDE logo, and a periodic STRIDE newsletter that included endorsements from local patients/stakeholders and clinicians about importance of the study.

Thrice-yearly Telephone Interviews

The follow-up interviews were completed by carefully selected research staff at the RAC who were rigorously trained in retention techniques (Table 1). Training sessions, led by the RAC director and two senior research staff, were held at the outset of the study. A video on interviewing techniques and bias was viewed and discussed during one of the sessions. Interviewers were certified only after they had: (1) passed quizzes on key aspects of the protocol, manual of procedures, and video; and (2) satisfactorily completed three sample follow-up interviews. To enhance fidelity, calls were monitored, frequently at first and subsequently on an as-needed basis.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Training of STRIDE Interviewers

| Characteristics |

| Mature, experienced in geriatrics |

| Pleasant, persistent, good communication skills |

| Successful experience with study retention |

| Understands importance of study |

| Available to work evening and weekend hours |

| Training |

| Study protocol and manual of procedures |

| Probing and minimizing bias |

| Active listening skills |

| “Customer” care relations |

| Motivational interviewing |

| Handling difficult circumstances, e.g. illnesses, deaths, etc. |

| Performance expectations |

| Identifying need for surrogate because of impairments in cognition/hearing |

| Introducing study to new surrogates or other “gatekeepers” unfamiliar with STRIDE |

| Use of standardized abbreviations in note fields |

| Use of nouns, rather than pronouns in note fields: “she” could be the participant, or one of several daughters |

Calls, which lasted less than 10 minutes on average, started one week before the 4-month target date with a 9-week window for completion. Up to 5 calls were made, with at least one in the morning, afternoon, evening, and weekend. The interviewers stated that they were calling from the Yale University STRIDE Study and wanted to review the participant’s fall calendar information. When needed, messages were left that stated the interviewer’s name and reason for the call, provided the toll-free phone number, and requested a good day/time for a return call. Secure remote access for direct data entry was established so that interviewers could complete calls from home (e.g., during evenings, weekends or inclement weather).

Given the large number of call assignments, i.e. up to 1800–1900 per month, interviewers had to work effectively as a team. Two lead interviewers reviewed and carefully planned call assignments based on schedules, participant/surrogate requests, and primary language. The field director established call priorities, reviewed difficult cases, and coordinated communication with CPM.

To assess the need for remedial training, the field director reviewed the frequency of call outcomes by interviewer ID. Productivity and success (e.g. number of calls, number of completed interviews) were determined using standard time estimates and benchmarks. Retraining was also provided at 6-month intervals and when the call management system (described below) was updated.

Systems Support

Data collection was completed using REDCap (http://project-REDCap.org), a secure, HIPAA-compliant web-based application.15 To enhance workflow, the DCC developed a customized “plug-in”, called the Follow-up Interview Manager (FIM). The FIM allowed the field director to manage interviewer case load and provided interviewers with helpful information about their open interviews, including: target date, contact information, detailed summary of prior contacts, log of notes, and designated surrogate. Open interviews were flagged if they were beyond the 9-week window and could be easily sorted by interviewer, target date, type of call (e.g. Month 16), number of calls, last call, and date of participant call back. Communication was enhanced through a cumulative log of notes entered by interviewers and operations staff (i.e., best times to call, assignment to a specific interviewer, etc.).

To effectively manage all aspects of the field operations, a custom software program, called the “Tracker”, was also developed. The notes field in the Tracker, which was linked to the notes in the FIM, facilitated communication of requests between interviewers and other study staff (e.g., mail follow-up packet to alternate address during specific months), and allowed interviewers to record relevant participant-specific information, such as birthday, vacation plans, and sick family members, that could help personalize follow-up calls. An integrated data system permitted contact information to be easily updated from different sources, increasing the likelihood of successful call attempts.

Mechanisms for Participants to Contact Study Team

The primary mechanism for participants (or surrogates) to contact the RAC was a toll-free number. Voicemail messages were checked twice daily (morning and afternoon) with the aim of returning calls within 24 hours. Clear and precise voicemail transcription by unblinded staff facilitated triage of messages to interviewers, data managers, field director, CPM, or clinical site, as appropriate. For example, calls about the intervention were forwarded to the clinical site. Although used less commonly, email and postal mail provided alternative mechanisms of contact with the RAC.

Activities at Clinical Sites

To enhance the visibility of STRIDE across the participating practices, research staff at the clinical sites provided study updates through local newsletters, in-service presentations and other forums. The content of these updates was informed through discussions with the Local and National Patients’ and Stakeholders’ Committees.

Special Circumstances

Participant Death

Deaths were ascertained by the RAC through multiple mechanisms, including a follow-up interview, an email or phone message from a family member or surrogate, a note of deceased from the post office, an online obituary, a serious adverse event (SAE) report from the clinical site, or a note in REDCap based on site-specific safety and outcomes surveillance.9, 11 A final interview was attempted with a surrogate at least four weeks after the death. If unsuccessful after two attempts, a condolence letter, written in close collaboration with the patient stakeholders, was sent, asking the surrogate if s/he would be willing to call the toll-free number to arrange a time for the final interview. Interviewers were prepared to describe the study to surrogates who might not have known about the participant’s involvement.

Reluctant Participant

When participants expressed an interest in withdrawing from the study, interviewers were trained to offer options that might be considered less “burdensome”, such as eliminating the use of fall calendars and reducing the frequency of follow-up interviews. If participants declined less intensive follow-up, they were asked for permission to continue tracking their healthcare utilization and medical records, i.e. partial withdrawal.9 Continued tracking was important because the adjudication protocol required that a self-reported serious fall injury be confirmed by another data source,11 and the Central IRB did not allow us to access healthcare utilization or medical records after a participant withdrawal, even if the fall injury occurred prior to the date of withdrawal.

If the interviewers learned of a withdrawal from a phone or email message and were unable to reach the participant by phone, a personalized letter was sent offering the option of partial withdrawal. Whenever possible, the reason for withdrawal was ascertained.

Unable to Locate Participant

When participants or surrogates could not be reached by phone after 3–4 attempts, interviewers called the additional contacts provided by the participant to inquire about a change in status (e.g., move or illness), or to complete the interview when appropriate. When these efforts were not successful, unblinded RAC staff asked the clinical site for updated contact information or report of death. If needed, a personalized letter was sent to participants indicating that the RAC was trying to reach them and requesting that they provide the best phone number and time to call via the toll-free number or email. For completeness, the RAC also reviewed “undeliverable” letters for new addresses from the Post Office and checked electronic obituaries, Whitepages, and reverse phone lookup.

Extending Follow-up Beyond 36 Months

Upon completion of the 36-month interview, participants were thanked for participating in the STRIDE Study and were asked for permission, i.e. reconsented, to extend follow-up through the end of March 2019. Participants were informed that their continued follow-up would allow us to better accomplish the goals of the study. Interviewers were trained to share the value of having participants continue their involvement in the study without exerting pressure. Participants who declined to complete any additional interviews were asked for permission to continue tracking their healthcare utilization and medical records through the end of March 2019.

Statistical Analyses

The percentages of participants who were lost to follow-up from deaths and withdrawals (partial or full) through March 2019 were calculated by age, sex, and clinical site. To account for differences in the duration of follow-up, values were also calculated as rates per 100 person-years. These analyses were repeated for the subsample (714 participants), the remaining 4,737 participants, and the subset of 1,214 participants who were enrolled contemporaneously with the subsample, although these results were not stratified by clinical site because of small numbers. Finally, completion of the follow-up interviews was calculated over time; and reasons for withdrawals (partial and full) were categorized.

RESULTS

Over a median [IQR] follow-up of 3.2 [2.8–3.7] years, 439 (8.1%) participants died and 600 (11.0%) withdrew consent or did not reconsent to extend follow-up beyond 36 months, yielding rates (per 100 person-years) of deaths and withdrawals of 2.6 and 3.6. Less than 5% of the withdrawals (29/600) occurred after completion of the 36-month follow-up interview. Table 2 provides results according to age, sex, and clinical site. As expected, mortality increased with advancing age and was higher for men than women. Although withdrawals also increased with advancing age, with rates (per 100 person-years) ranging from 1.7 for participants 70–74 years to 5.8 for those 85 years or older, they differed little by sex. Losses to follow-up did not differ appreciably by clinical site, with mortality rates ranging from 1.8 for Partners Healthcare to 3.9 for Reliant Medical Group and withdrawal rates ranging from 2.5 for Johns Hopkins Medicine to 4.6 for University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. As shown in Supplementary Table S2, mortality and withdrawal rates were higher for the random subsample of participants, and these differences were observed for all but two of the age- and sex-specific subgroups. However, among participants who were recruited contemporaneously, these differences were generally diminished for mortality and were largely eliminated for withdrawals (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 2.

Losses to Follow-up from Deaths and Study Withdrawals by Age, Sex and Clinical Site

| Characteristics | Enrolled | Died, not Withdrawn | Withdrawna | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | percent | rateb | n | percent | rateb | |

| Overall | 5,451 | 439 | 8.1 | 2.8 | 600 | 11.0 | 3.6 |

| Age, y | |||||||

| 70–74 | 1,037 | 31 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 49 | 4.7 | 1.7 |

| 75–79 | 1,857 | 103 | 5.5 | 1.7 | 192 | 10.3 | 3.3 |

| 80–84 | 1,344 | 114 | 8.5 | 2.7 | 154 | 11.5 | 3.6 |

| 85 or older | 1,213 | 191 | 15.7 | 5.4 | 205 | 16.9 | 5.8 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Men | 2,070 | 226 | 10.9 | 3.6 | 220 | 10.6 | 3.5 |

| Women | 3,379 | 213 | 6.3 | 2.1 | 380 | 11.2 | 3.7 |

| Clinical Site | |||||||

| Essentia Health | 462 | 47 | 10.2 | 3.5 | 60 | 13.0 | 4.4 |

| Healthcare Partners | 419 | 36 | 8.6 | 2.8 | 51 | 12.2 | 3.9 |

| Johns Hopkins Medicine | 620 | 45 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 47 | 7.6 | 2.5 |

| Mercy Health Network, U Iowa | 369 | 31 | 8.4 | 2.8 | 41 | 11.1 | 3.6 |

| Michigan Medicine, U Michigan | 549 | 49 | 8.9 | 2.8 | 54 | 9.8 | 3.1 |

| Mount Sinai Health System | 504 | 33 | 6.5 | 2.2 | 44 | 8.7 | 2.9 |

| Partners Healthcare | 735 | 42 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 79 | 10.7 | 3.5 |

| Reliant Medical Group | 602 | 74 | 12.3 | 3.9 | 85 | 14.1 | 4.5 |

| U Pittsburgh Medical Center | 650 | 47 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 91 | 14.0 | 4.6 |

| U Texas Medical Branch | 541 | 35 | 6.5 | 2.2 | 48 | 8.9 | 3.0 |

Includes partial and full withdrawals. 29 (4.8%) of the withdrawals occurred after completion of the 36-month follow-up interview, but before the end of the extended follow-up on March 31, 2019.

Per 100 person-years of follow-up

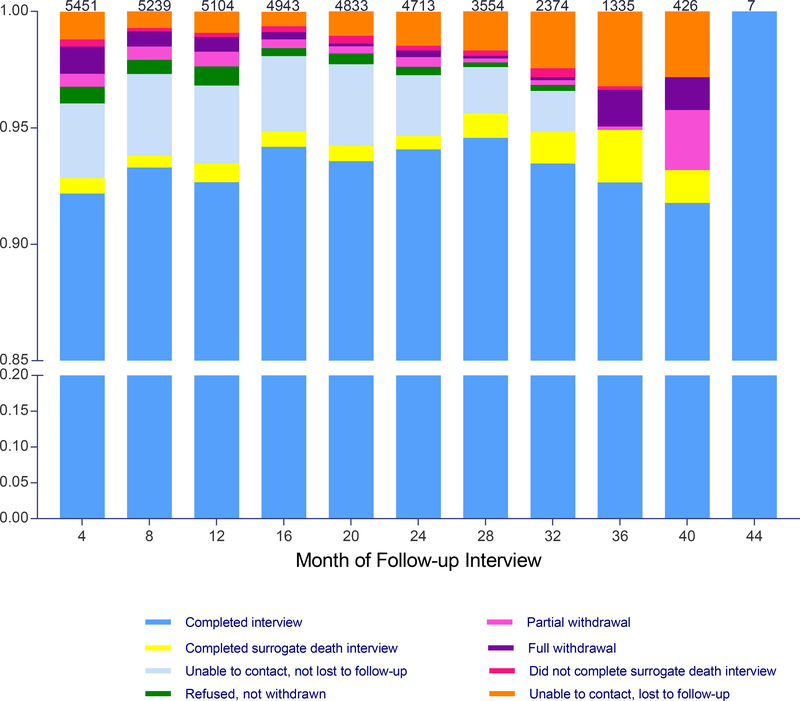

As shown in Figure 1, the completion rate for the follow-up interviews, including surrogate death interviews, was greater than 93% at each time point. Most participants completed all (71.8%) or all but one (9.2%) of the follow-up interviews. At each time point, the most common reason for not completing a follow-up interview was unable to contact (with or without loss to follow-up), with rates ranging from 2.8% at 40 months to 4.6% at 20 months. Although the rate of partial withdrawal was less than 0.7% at each interview other than 40 months, the absolute number over time was not insubstantial at 170.

Figure 1.

Completion of the follow-up interviews over time. Rates are based on the number of non-decedents from the prior interview, which is provided at the top of each bar. A diminishing number of participants who were enrolled later in the study were scheduled for follow-up interviews beyond 24 months. As described in the Methods, participants had to be reconsented at 36 months. A surrogate death interview was completed for 299 (76.7%) of the 390 decedents who had not completed the final follow-up interview, been lost to follow-up, or withdrawn partially from the study. The designation, “Unable to contact, lost to follow-up”, was made retrospectively at the end of the study.

The reasons for study withdrawals are provided in Table 3. Overall, the most common reasons for study withdrawal were illness, unable to contact for reconsent at 36 months, study not useful, too busy, and no longer interested, although 13.8% of participants provided more than one reason. Differences in reasons between the partial and full withdrawals were relatively modest except for illness, unable to contact for reconsent at 36 months, and declined to extend follow-up beyond 36 months.

Table 3.

Reasons Provided by Participants for Study Withdrawal

| Overall N=600 |

Partiala N=215 |

Full N=385 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

n (%) |

|||

| Illness | 101 (16.8) | 55 (25.6) | 46 (11.9) |

| Unable to contact for reconsent at 36 months | 75 (12.5) | 0 | 75 (19.5) |

| Study not useful | 50 (8.3) | 23 (10.7) | 27 (7.0) |

| Too busy | 42 (7.0) | 12 (5.6) | 30 (7.8) |

| No longer interested | 42 (7.0) | 15 (7.0) | 27 (7.0) |

| Declined to extend follow-up beyond 36 months | 21 (3.5) | 0 | 21 (5.5) |

| Moved out of area or to facility | 15 (2.5) | 12 (5.6) | 3 (0.8) |

| Did not understand what study involved | 12 (2.0) | 4 (1.9) | 8 (2.1) |

| Participant unable and surrogate refused | 12 (2.0) | 6 (2.8) | 6 (1.6) |

| No longer receiving primary care at assigned practice | 8 (1.3) | 1 (0.5) | 7 (1.8) |

| Other | 107 (17.8) | 46 (21.4) | 61 (15.8) |

| Multiple reasons | 81 (13.5) | 28 (13.0) | 53 (13.8) |

| No reason given | 34 (5.7) | 13 (6.0) | 21 (5.5) |

Participant declined to complete any additional follow-up interviews, but permitted continued tracking of his/her health care utilization and medical records.

DISCUSSION

The procedures described in the current manuscript allowed us to approximate an ambitious goal of limiting losses to follow-up for reasons other than death to 3% per year in the absence of a serious fall injury. Over a follow-up period of 24 to 44 months, the rates of withdrawals and deaths per 100 person-years were 3.6 and 2.6, respectively, compared with the projected rates of 3.0 and 7.0, indicating that retention of participants exceeded the estimates used in the original sample size calculations9. Because the reported rates do not account for losses that occurred after a serious fall injury, the STRIDE Study should maintain its projected 90% power to detect a 20% reduction in serious fall injuries.

The 21 participants who declined to extend their follow-up beyond the originally planned 36 months were included as study withdrawals. Many of these participants told the interviewers that they had fulfilled their original commitment and did not feel comfortable changing the agreement, highlighting the importance of establishing clear expectations at the outset of a trial. Another 75 participants could not be contacted for reconsent at 36 months. Together, these two groups represented about 16% of the study withdrawals, making our retention rate conservative. Future trials might consider including language about the possibility of extending follow-up in the informed consent process. Not surprisingly, the most common reason for study withdrawal was illness. The majority of participants (mean age, 80 years) had multimorbidity, all were at increased risk for falls, and only a minority reported excellent or very good self-reported health.10 Nonetheless, the observed mortality rate was less than half the projected rate, suggesting the possibility of a healthy enrollee effect.

The withdrawal rate increased as expected with advancing age, was comparable for men and women, and did not differ much across the ten clinical trial sites. Because more than a third of the participants who withdrew from the study permitted continued tracking of their health care utilization and medical records, it will be possible to confirm their previously reported fall injuries.11 We found that the withdrawal rate was higher among the subsample of 714 participants (compared with the remaining 4,737 participants) who had agreed to the expanded interviews at baseline, 12 months and 24 months, which usually took about 10 additional minutes to complete, suggesting potential trade-offs between retention and collection of additional data. Participants in the subsample also had higher mortality, a finding that could not be explained by differences in age or sex. These subsample differences, however, were diminished or eliminated when comparisons were restricted to participants who were recruited contemporaneously, suggesting that the mix of participants may have changed over the 20-month recruitment period.

Given the importance of retention for optimizing the power, validity and generalizability of a clinical trial, we implemented a series of retention-enhancing procedures (described in Methods) that were based on best practices and our collective clinical trial experience. During the trial, we faced a series of challenges, both expected and unexpected, that might have diminished retention. These challenges, along with strategies designed to optimize retention, are summarized in Table 4. A guiding principle was that every contact between research staff and participant contributes to the likelihood that the participant will remain in the trial. Interviewers asked about falls and injuries since the last completed interview, enhancing ascertainment in the setting of one or more missed interviews. While face-to-face contacts may help to establish and strengthen connections between research staff and participants, all follow-up interviews in STRIDE were completed over the phone, obviating the need for vulnerable older persons to travel to an assessment center.

Table 4.

Challenges and Strategies to Optimize Retention in STRIDE Study

| Challenges | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Caller ID | Have same interviewer with same number call participant over time |

| Era of robocalls | Leave clear and distinct message(s) on voice mail, while holding on phone to give participant time to answer |

| Participants have busy schedules | Follow-up Interview Manager provided days/times when prior calls were completed, tracked number and days/times of attempted calls, and flagged interviews that were overdue. |

| Large volume of calls | Effective communication among interviewers |

| No face-to-face contact between interviewers and participants | Ensure that all forms of communication with participants are clear and consistent Patient stakeholders reviewed all written correspondence for readability. Prior to each follow-up interview, reminder letters were mailed with the next set of fall calendars. |

| Contact information is incomplete or not current | Call alternative contact(s) Unblinded RAC staff request current contact information from clinical site. |

| Reluctant participant | Be respectful but persistent Listen carefully Offer to call back on another day and/or time Avoid getting to “no” by offering to skip current interview and trying again in 4 months Discuss difficult cases with field director, leading to customized approach |

| Participant appears to be confused | Reach out to alternative contact and ask him/her to serve as surrogate |

| Unexpected events | Interviewers were trained to be prepared for uncommon events, e.g. recent death or illness of a participant or loved one. Adjust call schedules due to extraordinary circumstances at a clinical site, e.g. hurricane, wildfires, school shooting Work with clinical sites and CPM to modify communication with participants who evidence heightened sensitivity |

| Allow more time to complete interview |

Abbreviations: CPM, Central Project Management; RAC, Recruitment and Assessment Center

Many older persons participate in research studies out of a sense of altruism.16 For clinical trials such as STRIDE, participants who are assigned to an active treatment group may also benefit from the intervention being evaluated. Because the blind has not yet been broken, it was not possible to determine whether retention differed by treatment group. Because the interviews were completed by phone, our findings may not be generalizable to other modes of follow-up. Despite these limitations, STRIDE is one of the few trials, to our knowledge, that has rigorously evaluated retention of older participants, particularly those who are frail or at risk of falls. According to a recent systematic review17 and an earlier Cochrane review,18 only four prior reports have empirically evaluated retention among persons 70 years or older,19–22 and all four evaluated response rates to a postal questionnaire, with follow-up ranging from only 4 months21 to 2 years.20

In summary, completion of the thrice-yearly follow-up interviews in STRIDE was high, and retention of participants over 44 months exceeded the original projections. The procedures used in STRIDE, together with lessons learned, should assist other investigators who are planning or conducting large pragmatic trials of vulnerable older persons.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Document S1. Falls and Older Adults, National Institute on Aging

Supplementary Document S2. Acknowledgements

Supplementary Table S1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Supplementary Table S2. Losses to Follow-up from Death and Study Withdrawals by Subsample Status, Age, and Sex

Supplementary Table S3. Losses to Follow-up from Death and Study Withdrawals by Subsample Status, Age, and Sex among Participants Who Were Enrolled Contemporaneously

Acknowledgments:

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Role of the Sponsors:

The organizations funding this study had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02475850

REFERENCES

- 1.Akl EA, Briel M, You JJ et al. Potential impact on estimated treatment effects of information lost to follow-up in randomised controlled trials (LOST-IT): systematic review. BMJ 2012;344:e2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Sample size slippages in randomised trials: exclusions and the lost and wayward. Lancet 2002;359:781–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szklo M Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiol Rev 1998;20:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mody L, Miller DK, McGloin JM et al. Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:2340–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonk J A road map for the recruitment and retention of older adult participants for longitudinal studies. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58 Suppl 2:S303–S307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcantonio ER, Aneja J, Jones RN et al. Maximizing clinical research participation in vulnerable older persons: identification of barriers and motivators. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1522–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levkoff S, Sanchez H. Lessons learned about minority recruitment and retention from the Centers on Minority Aging and Health Promotion. Gerontologist 2003;43:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Provencher V, Mortenson WB, Tanguay-Garneau L, Belanger K, Dagenais M. Challenges and strategies pertaining to recruitment and retention of frail elderly in research studies: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2014;59:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhasin S, Gill TM, Reuben DB et al. Strategies to Reduce Injuries and Develop Confidence in Elders (STRIDE): a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial of a multifactorial fall injury prevention strategy: design and methods. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018;73:1053–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill TM, McGloin JM, Latham NK et al. Screening, recruitment, and baseline characteristics for the Strategies to Reduce Injuries and Develop Confidence in Elders (STRIDE) Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018;73:1495–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganz DA, Siu AL, Magaziner J et al. Protocol for serious fall injury adjudication in the Strategies to Reduce Injuries and Develop Confidence in Elders (STRIDE) study. Inj Epidemiol 2019;6:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol 1990;45:P239–P243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment 2011;18:263–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jette AM, Haley SM, Ni P, Olarsch S, Moed R. Creating a computer adaptive test version of the late-life function and disability instrument. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:1246–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baczynska AM, Shaw SC, Patel HP, Sayer AA, Roberts HC. Learning from older peoples’ reasons for participating in demanding, intensive epidemiological studies: a qualitative study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017;17:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacey RJ, Wilkie R, Wynne-Jones G, Jordan JL, Wersocki E, McBeth J. Evidence for strategies that improve recruitment and retention of adults aged 65 years and over in randomised trials and observational studies: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2017;46:895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brueton VC, Tierney J, Stenning S et al. Strategies to improve retention in randomised trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:MR000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cockayne S, Torgerson DJ. A randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of offering study results as an incentive to increase response rates to postal questionnaires [ISRCTN26118436]. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell N, Hewitt CE, Lenaghan E et al. Prior notification of trial participants by newsletter increased response rates: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:1348–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacLennan G, McDonald A, McPherson G, Treweek S, Avenell A, Group RT. Advance telephone calls ahead of reminder questionnaires increase response rate in non-responders compared to questionnaire reminders only: The RECORD phone trial. Trials 2014;15:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avenell A, Grant AM, McGee M et al. The effects of an open design on trial participant recruitment, compliance and retention--a randomized controlled trial comparison with a blinded, placebo-controlled design. Clin Trials 2004;1:490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Document S1. Falls and Older Adults, National Institute on Aging

Supplementary Document S2. Acknowledgements

Supplementary Table S1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Supplementary Table S2. Losses to Follow-up from Death and Study Withdrawals by Subsample Status, Age, and Sex

Supplementary Table S3. Losses to Follow-up from Death and Study Withdrawals by Subsample Status, Age, and Sex among Participants Who Were Enrolled Contemporaneously