Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the change in six-minute walk test (6-MWT) relative to changes in key functional capacity measures after 16-week of exercise training in older (≥65 years) heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) patients.

Design

Prospective, randomized single blinded (by researchers to patient group) comparison of two groups of HFpEF patients.

Settings

Hospital and clinic records. Ambulatory outpatients.

Participants

Participants (N=47) randomized to attention control (n=24, AC) or exercise training (n=23, ET) group

Intervention

The ET group performed cycling and walking at 50-70% VO2peak intensity (3 days per week, 60 min each session).

Main outcome measures

Peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak), ventilatory threshold (VT) and 6-MWT were measured at baseline and after 16-week study period.

Results

At follow-up, 6-MWT was higher than at the baseline in both ET (11%, P = 0.005) and AC (9%, P = 0.004). In contrast, VO2peak and VT values increased in the ET (19 and 11%, respectively; P = 0.001), but decreased in AC at follow-up (2% and 0%, respectively). The change in VO2peak vs 6-MWT after training was also not significantly correlated in the AC (r = 0.01, P = 0.95) nor the ET (r = 0.13, P = 0.57) groups. The change in 6-MWT and VT (an objective submaximal exercise measure) was also not significantly correlated in the AC (r = 0.08, P = 0.74) or ET (r =0.16, P = 0.50) groups.

Conclusions

The results of this study challenge the validity of using the 6-MWT as a serial measure of exercise tolerance in elderly HFpEF patients and suggest that submaximal and peak exercise should be determined objectively by VT and VO2peak in this patient population.

Keywords: Peak oxygen uptake, ventilatory threshold, validity

INTRODUCTION

Exercise intolerance is the primary symptom in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).1 Moderate-continuous endurance exercise training is a well-established non-pharmacologic treatment for medically stable chronic HF patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). However, few studies have evaluated the potential benefits of exercise training in elderly patients with HFpEF.2 Peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) and the ventilatory threshold (VT) are currently considered to be the most objective measures of functional capacity in HF patients.3 In clinical setting, the six-minute walk test (6-MWT) has become a widely used measure of functional capacity in patients with HF.3 However, the relationship between the 6-MWT and objective measures of exercise tolerance in older HFpEF patients, has not been adequately examined. It was hypothesized that the change in 6-MWT would be significantly correlated with changes in key measures of functional capacity (VO2peak and VT), in older HFpEF patients participating in an exercise training intervention.

METHODS

Patients Population.

Forty-seven patients (41 women and 6 men), participated in a National Institutes of Health-funded clinical trial for patients with HF aged ≥ 65 years old. The diagnosis of HF was based on clinical criteria as previously described that included a HF clinical score from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey-I of ≥3, and those used by Rich et al.4 and verified by a board certified cardiologist. Patients’ eligibility, trial protocol, participant characteristics, and main outcomes have been previously described.1,2,5

Study Protocol.

The study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board for Protection of Human Subjects. This was a prospective, randomized single blinded (by researchers to patient group) comparison of two groups of HFpEF patients. During the 16-week intervention period, the exercise training group (ET) participated in a traditional endurance type exercise program, while the attention control group (AC) received no exercise interventions. All tests and measurements were performed in both groups at entry and after the 16-week study period and have been previously described.1 Participants performed a symptom-limited exercise test in the upright position on an electronically braked bicycle (CPE 2000, MedGraphics, Minneapolis, MN). The exercise tests were performed with expired gas analysis MedGraphics Breeze Ex) for the determination of VO2peak and VT.

Exercise training program.

The duration of the exercise training was a minimum of 16-weeks for a total of 48 sessions and was conducted three days a week with each session lasting a total of 60 minutes. After 10 minutes of light exercise and stretching, patients exercised an equal time on a cycle ergometer (Schwinn Airdyne) and over ground walking on an indoor track. The duration of each modality increased gradually to a maximum of 20 minutes per session. The goal of exercise program was to increase each patient’s total exercise volume by 5% each week. Throughout the training period, the exercise intensity was maintained between 50 and 70% of the VO2peak and regulated with heart rate and perceived exertion.

Statistical analyses.

Power analyses for the study are described in prior publication.2 Before all statistical analyses, data were checked for violations of normality using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilks tests. “Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances” used for the homogeneity of variance assumption. Independent t-test used for comparison of variables between groups. Given the large number of comparisons, Bonferroni adjustment was used to reduce potential of Type I error. To adjust for group differences at follow-up, data was analyzed using a univariate analysis of covariance. Differences between follow-up and baseline data also presented as percent change. The relationship between variables at baseline, and for change from baseline to follow-up, were examined using Pearson correlation coefficient. SPSS software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) used for all statistical analyses. All reported P-values were two-sided and were significant if ≤0.05.

RESULTS

Exercise testing responses for submaximal and peak variables are displayed in Table 1. There were no significant differences between AC and ET groups for VO2peak, 6-MWT and other analyzed variables at baseline. Only VT (mL·kg−1·min−1) was significantly different (P = 0.04) between AC and ET at baseline. Exercise training compliance, adherence and adverse events were acceptable and have been presented in the main outcome paper.5

Table 1.

Exercise testing values of the study population at baseline and follow-up. Values are mean ± SD.

| ATTENTION CONTROL GROUP (AC) n=24 | EXERCISE TRAINING GROUP (ET) n = 23 | Follow-up ADJUSTED ** | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASELINE | FOLLOW-UP | P value | BASELINE | FOLLOW-UP | P value- | AC | ET | P value | |

| Peak Exercise (Bike) | |||||||||

| Workload (W) | 46.2 ± 14.8 | 47.3 ± 19.2 | 0.66 | 51.6 ± 19.4 | 59.8 ± 19.9 | 0.01 | 49.6 ± 2.7 | 57.5 ± 2.7 | 0.048 |

| Time (s) | 383 ± 119 | 353 ± 144 | 0.03 | 400 ± 132 | 484 ± 126 | 0.001 | 360 ± 17 | 477 ± 17 | 0.002 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 136 ± 17 | 129 ± 20 | 0.01 | 133 ± 20 | 138 ± 16 | 0.25 | 128 ± 2.8 | 138 ± 2.7 | 0.015 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||||||

| Systolic | 185 ± 28 | 175 ± 27 | 0.04 | 186 ± 27 | 187 ± 22 | 0.78 | 175 ± 4 | 187 ± 4 | 0.049 |

| Diastolic | 86 ± 12 | 84 ± 11 | 0.42 | 89 ± 8 | 88 ± 9 | 0.76 | 85 ± 2 | 87 ± 2 | 0.452 |

| VO2 (mL·min−1) | 994 ± 263 | 972 ± 261 | 0.59 | 1053 ± 240 | 1255 ± 322 | 0.001 | 998 ± 38 | 1227 ± 39 | 0.001 |

| VO2 (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 12.7 ± 3.2 | 12.6 ± 3.4 | 0.85 | 13.5 ± 2.3 | 16.0 ± 2.6 | 0.001 | 12.9 ± 0.4 | 15.7 ± 0.4 | 0.001 |

| VCO2 (mL·min−1) | 1119 ± 308 | 1065 ± 366 | 0.25 | 1155 ± 300 | 1400 ± 356 | 0.001 | 1083 ± 39 | 1382 ± 39 | 0.001 |

| VE/VCO2 ratio | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.695 |

| Respiratory exchange ratio | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.55 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.17 | 1.1 ± 0.01 | 1.1 ± 0.02 | 0.175 |

| VT (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 8.3 ± 1.3 | 8.3 ± 2.2 | 0.88 | 9.3 ± 1.5* | 10.4 ± 1.4 | 0.001 | 8.6 ± 0.4 | 10.0 ± 0.4 | 0.010 |

| 6-MWT (m) | 402 ± 142 | 430 ± 125 | 0.004 | 455 ± 68 | 506 ± 53 | 0.005 | 449 ± 12 | 487.1 ± 11.4 | 0.028 |

P < 0.05 (difference between AC and ET at baseline)

Adjusted for baseline values using ANCOVA

VO2: Oxygen uptake

VCO2: Carbon dioxide production

VE/ VCO2: Ventilatory equivalent from carbon dioxide

VT: Oxygen consumption at ventilation threshold

6-MWT: 6-minute walk test

After the 16-week intervention, the 6-MWT distance at follow-up was higher than at baseline test in both AC (9%, P = 0.04) and ET (11%, P = 0.05). In contrast, after the 16 week training period VO2peak and VT values were increased (P = 0.01) in ET and showed a decrease or no change in AC. In addition, the 6-MWT (P = 0.02), VO2peak (P = 0.001), and VT (P = 0.01) were higher in the ET than AC group at 16 weeks. As a result, the mean change (i.e., the difference between follow-up and baseline data expressed as % change) was 19% and 18% higher in VO2peak (mL·min−1 and mL·kg−1·min−1, respectively), (P = 0.001), and 11% higher VO2 at VT (expressed as mL·kg−1·min−1), (P = 0.001) for ET group. In contrast, no significant change was seen in the AC for these variables (Table 1).

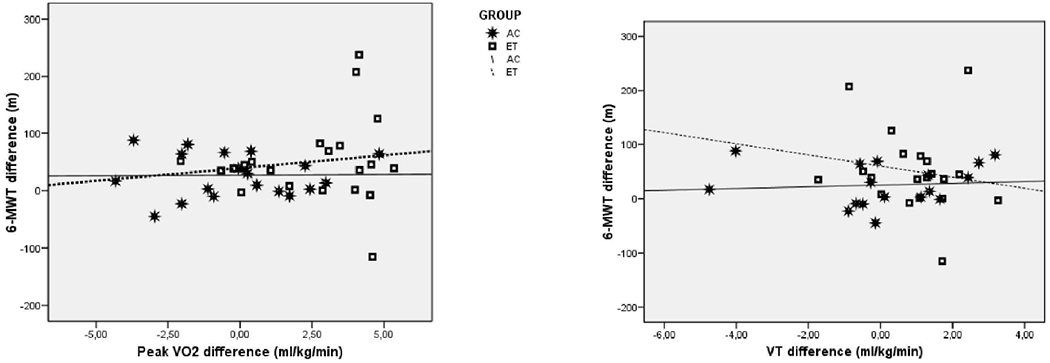

Non-significant correlations were observed between the change in VO2peak (mL·kg−1·min−1) and the change in 6-MWT in the AC (r = 0.01, P = 0.95) and the ET (r = 0.13, P = 0.57) groups (Figure 1). Furthermore, non-significant correlations were observed between the change in submaximal exercise variables (6-MWT vs. VT), in the AC (r = 0.08, P = 0.74) and the ET (r = 0.16, P = 0.50) groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship between the change in 6-MWT (m) with the change in VO2peak (mL·kg−1·min−1) and the change in VT (ml·kg−1·min−1) for Attention Control (AC) group and Exercise Training (ET) group.

DISCUSSION

The current study provides the first examination of the change in 6-MWT relative to changes in key functional capacity outcomes measures after exercise training in older HFpEF patients. Data from this randomised clinical trial demonstrates that there is a no meaningful relationship between the changes in 6-MWT and VO2peak in either the AC or ET groups (Figure 1). These findings are in accord with the results of previous investigations indicating that 6-MWT may not be an optimal surrogate for VOpeak and VT in elderly HFrEF patients.6 Contrary to these findings, a previous study suggested the potential usefulness of 6-MWT for evaluating functional status in women with HFpEF. However, this study was based on the change in 6-MWT performance after a walking intervention and did not explore the relationship of 6-MWT to objective measures of exercise capacity such as VO2 peak and VT.7 Forman et al.3 demonstrated that 6MW distance significantly correlated with VO2peak in a large group of HFrEF patients and suggested that the 6MWT may be a substitute for a cardiopulmonary exercise test. However, the present study had the following advantages: 1) it was conducted on a well characterized cohort of HFpEF versus HFrEF patients, recognizing that the physiopathology and prognosis of HFrEF are different from HFpEF patients, 2) it was conducted entirely with elderly HF patients, recognizing that HFpEF and HFrEF are differentially influenced by aging8 and 3) the test administrator was blinded to patient group assignment.

Furthermore, the lack of correlation between the change in VT and 6-MWT, both submaximal exercise variables, suggests that 6-MWT does also not appear to be an acceptable surrogate measure for submaximal exercise performance in HFpEF patients. Although VT can be difficult to identify in some HF patients, and may have substantial inter-observer and intra-observer variability9, in the present study VT was determined by two different methods and was detectable in 95% of the patients. Previous studies have determined that VT is a useful noninvasive outcome measure in this HFpEF10 and with good reproducibility.

In the present investigation, the ET group experienced an average of 11% in 6-MWT which parallels the change observed in VT. Furthermore, the ET showed an 18% increase in VO2peak. In contrast the AC group demonstrated a 9% increase in the 6-MWT over the 16 week period without any significant change in VO2peak and VT (Table 1). These findings have two important implications; 1) the 6-MWT may have demonstrated a significant “practice effect” in elderly HFpEF patients, despite the previous report of good reliability7, and 2) the “gold-standard” submaximal and peak exercise capacity measures (i.e., VT and VO2peak, respectively) responded as expected in the ET and AC groups.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

Limitations of the present study include the small sample size as well as the homogeneity of the sample (i.e., mostly older female patients with HFpEF), making it difficult to generalize these findings to other clinical populations. Although the sample size is relatively small, the well-defined HFpEF group and rigorous protocol (i.e., randomized and blinded testing to patient group, with careful serial measures of VO2peak and 6-MWT) are major strengths of this investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the findings of this study challenge the utility of 6-MWT as a reliable serial measure of exercise intolerance in trials of older HFpEF patients and suggests that measured VO2peak and VT should be used as the primary outcome measures for serial assessment of exercise tolerance in this patient population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the following National Institutes of Health research grants: R01AG18915, P30AG021332, R01HL093713, and R01AG020583

Abbreviations

- 6-MWT

six-minute walk test

- AC

attention control

- ET

exercise training

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- VO2peak

peak oxygen uptake

- VT

ventilatory threshold

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There are not conflicts of interest

Reprints are not available

Clinical Trial Registration number: NCT00959660

REFERENCES

- 1.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, John JM, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Kitzman DW. Determinants of exercise intolerance in elderly heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(3):265–274. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109711015476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Herrington DM, et al. Effect of endurance exercise training on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: A randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(7):584–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forman DE, Fleg JL, Kitzman DW, et al. 6-min walk test provides prognostic utility comparable to cardiopulmonary exercise testing in ambulatory outpatients with systolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(25):2653–2661. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.1010 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(18): 1190–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Little WC. Exercise training in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction / clinical perspective. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2010;3(6):659–667. http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/content/3/6/659.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maldonado-Martin S, Brubaker PH, Kaminsky LA, Moore JB, Stewart KP, Kitzman DW. The relationship of a 6-min walk to VO(2 peak) and VT in older heart failure patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(6):1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gary RA, Sueta CA, Rosenberg B, Cheek D. Use of the 6-minute walk test for women with diastolic heart failure. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24(4):264–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitzman DW, Upadhya B. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A heterogenous disorder with multifactorial pathophysiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(5):457–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baba R, Nagashima M, Goto M, et al. Oxygen uptake efficiency slope: A new index of cardiorespiratory functional reserve derived from the relation between oxygen uptake and minute ventilation during incremental exercise. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28(6): 1567–1572. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109796004123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marburger CT, Brubaker PH, Pollock WE, Morgan TM, Kitzman DW. Reproducibility of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(7):905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]