Abstract

Background

Few head-to-head comparisons of the different classes of laxatives have been conducted.

Objective

The objective of this work is to compare the efficacy of lactulose plus paraffin vs polyethylene glycol in the treatment of functional constipation (non-inferiority study).

Methods

This randomised, parallel-group, multicentre phase 4 study recruited patients with functional constipation diagnosed according to Rome III criteria. Patients received lactulose plus paraffin or polyethylene glycol for 28 days. The primary end point was the change from baseline in the Patient Assessment of Constipation–Symptoms (PAC-SYM) score.

Results

A total of 363 patients were randomised to lactulose plus paraffin (n = 179) or polyethylene glycol (n = 184). On day 28, the mean PAC-SYM score decreased significantly vs baseline with both treatments (p < 0.001). The lower boundary of the 95% CI exceeded the pre-specified limit of −0.25, therefore establishing non-inferiority of lactulose plus paraffin vs polyethylene glycol. At least one adverse event occurred in 20 patients (11.2%) in the lactulose plus paraffin group and in 26 patients (14.2%) in the polyethylene glycol group, most of which were of mild or moderate severity and unrelated to study drugs.

Conclusion

Lactulose plus paraffin may be used interchangeably with polyethylene glycol for the pharmacological treatment of functional constipation.

Trial registration: EudraCT number 2015-003021-34

Keywords: Constipation, lactulose, laxative, Melaxose, Movicol, paraffin, polyethylene glycol, randomised study, quality of life

Key summary

Established knowledge on this subject

Functional constipation is a common condition that can have a significant effect on patient quality of life.

Although a wide variety of laxatives are available, few head-to-head comparative studies have been conducted. Additionally, most studies have failed to assess the impact of laxative treatments on patient quality of life.

Lactulose plus paraffin (Melaxose) and polyethylene glycol (PEG, Movicol) both have been marketed since the 1990s for the treatment of constipation.

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

This study is the first to establish non-inferiority of the combination of lactulose and paraffin vs PEG in functional constipation in adults, based on the assessment of symptom improvement.

Both agents also improved patient quality of life from baseline.

These findings suggest that lactulose plus paraffin may be used interchangeably with PEG for the treatment of functional constipation in adults.

Introduction

Functional constipation is a very common condition. Estimates of its prevalence range from 2% to 27% of the population depending on the study, and the worldwide prevalence is estimated at 14%.1 However, the real numbers are likely to be higher, as at least 65% of patients with constipation do not seek immediate medical advice, but use over-the-counter laxatives instead.2

Functional constipation has a strong impact on quality of life (QoL) and a high individual and societal economic burden. Moreover, for up to 25% of the population, it is more than a minor annoyance, and can be a long-lasting and sometimes severe condition that has a significant, even debilitating, effect on their QoL.3

Management of constipation typically begins with non-pharmacological measures, including exercise and increased dietary fibre and fluid intake. These general measures often fail to relieve constipation, so therapies such as bulking agents, osmotic laxatives, stimulant laxatives and stool softeners are used to promote regular bowel movements.4 A wide variety of laxatives are available, many of which are effective and well tolerated. Osmotic laxatives, such as lactulose and polyethylene glycol (PEG), are recommended in adults and the elderly as first-line medication.5–9

Melaxose (Biocodex, France) has been marketed for the treatment of symptomatic constipation in adults since 1997. It contains micronised lactulose coated with a thick layer of paraffin. Movicol (PEG 3350) has been marketed since 1995 for the treatment of constipation both for adults and the paediatric population.

Although the vast majority of trials evaluating PEG and lactulose report improvements in the number of bowel movements per week and in certain symptoms of functional constipation,10 few head-to-head comparisons have been conducted to determine whether one laxative class is superior to another. It is also largely unknown whether laxative treatments address the impaired QoL observed in patients with functional constipation, as most studies have failed to assess it.

The objective of the present study was to compare, for the first time in a head-to-head manner, the combination of lactulose and paraffin with PEG, and to determine whether lactulose plus paraffin is non-inferior to PEG in the treatment of constipation. PEG was chosen as the comparator because it is among the most commonly prescribed laxatives and is recommended in first-line therapy by local and international guidelines.6–8

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

This was a randomised, parallel-group, phase 4 multicentre study (EudraCT number: 2015-003021-34) with masked treatment allocation.

Adult outpatients (aged ≥18 years) attending one of 71 community gastroenterologist or general practitioner practices in France were included if they had functional constipation according to Rome III criteria and a Patient Assessment of Constipation–Symptoms (PAC-SYM) score of 18 or greater at the baseline visit (day 0). Patients were excluded if they had organic constipation or another chronic digestive condition that could confound the evaluation of constipation, including organic (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease, neoplasia, intestinal obstruction) or functional (irritable bowel disease) disease, or a history of abdominal surgery (except appendectomy). The patients presenting with constipation secondary to chronic disease such as endocrine, metabolic or neurologic diseases were excluded.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est 6 (ethics committee) on 16 November 2015. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to initiating any procedures. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Trial conduct and study drugs

Patients attended the study site four times. At the inclusion visit (day −14), patients received information on the study and signed the informed consent form, and the inclusion criteria were checked. Patients were instructed to stop current treatment for constipation (wash-out) and received four Microlax (Johnson & Johnson, USA) enemas as rescue medication, to be used only after three days without bowel movement.

Between day 0 and day 28, patients received, according to the randomisation list, two tablespoons of Melaxose (each containing 1.75 g of lactulose and 2.145 g of paraffin) or one sachet of Movicol (containing 13.125 g of PEG 3350) per day, which are the recommended doses according to the labels.11,12

A randomisation list had been prepared prior to the study, and investigators allocated treatment numbers in chronological order. Because the appearance of the study drugs was different, a double-blind design was not possible and masked allocation was used: The outer packaging of the study drugs had identical appearance and the investigator could not know the patient’s treatment beforehand (the patient would know only after opening the outer packaging). This procedure is in line with the CONSORT and GRADE guidelines.13,14

Laxatives other than the study drugs as well as opioids were prohibited, and the dosing of antidepressants or drugs that could cause constipation could not be modified during the study.

Procedures and outcomes

Primary end point

The PAC-SYM is a self-administered 12-item questionnaire with a recall period of 2 weeks, developed to measure the presence and severity of constipation-related symptoms.15 It is divided into three subscales: abdominal symptoms (bloating, discomfort, pain and cramps), stool symptoms (incomplete bowel movement, false alarm, straining, too hard and too small) and rectal symptoms (painful bowel movement, burning and bleeding or tearing). Each item is scored from 0 (symptom absent) to 4 (very severe), therefore, the total score ranges from 0 to 48. In this study, the total and subscale scores were adjusted to values ranging from 0 to 4 according to a previously described validation method.15

Secondary end points

The Patient Assessment of Constipation–Quality of Life (PAC-QOL) questionnaire assesses constipation-related impairment on four subscales: physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort, worries and concerns, and satisfaction.16 PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL were completed at all visits (day −14, day 0, day 14 and day 28).

The number and consistency of spontaneous bowel movements (SBM) were recorded daily in the patient’s diary from day −14 to day 28. Spontaneous was defined as not induced by any drug other than lactulose plus paraffin or PEG. Stool consistency was assessed using the Bristol scale (hard: 1–2; normal: 3–5; liquid: 6–7).

The patient’s global impression of change (PGIC; change to daily activities produced by study treatment, constipation symptoms and QoL) was assessed using the seven-point Likert scale ranging from ‘no change (or worse)’ to ‘markedly better’. Investigator’s global assessment of treatment efficacy was assessed using the five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘not effective at all’ to ‘very effective’.

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded throughout the study.

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation was based on the change from baseline in the PAC-SYM score and data reported in previous placebo-controlled studies.15,17–21 A sample size of 142 patients was calculated to provide 80% power to detect the difference between treatments with a two-sided significance level of 5% (or a one-sided significance level of 2.5%), assuming a non-inferiority margin of −0.25 and an SD of 0.75. The sample size was increased to 157 to account for 10% of patients being non-evaluable for PAC-SYM.

Statistical analysis

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population included all patients assigned a randomisation number. The safety population included all randomised patients who received 1 or more doses of a study drug. The per-protocol (PP) population included all randomised patients with no major protocol deviation.

For quantitative variables, mean, SD, median, minimum and maximum, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. For qualitative variables, frequency tables were prepared.

Non-inferiority of lactulose plus paraffin to PEG with regard to the primary end point of change in the mean PAC-SYM score at day 28 would be established if the lower limit of the 95% CI of the difference between groups, analysed using analysis of covariance, was greater than the predefined limit of −0.25. The primary analysis was carried out in the PP population. Sensitivity analyses were carried out in the ITT population.

SBM frequency per week was calculated as the mean of available entries in the patient diary over that week. Stool consistency was calculated as the weekly average number of stools by category. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

A total of 412 patients were screened for the study (Figure 1). From April 2016 to December 2017, 363 patients across 71 sites were included. One patient randomly assigned to PEG was included erroneously, never received the study drug and was included in the ITT, but not the safety, population. The ITT population comprised 363 patients (lactulose plus paraffin, n = 179; PEG, n = 184) and the safety population, 362 patients. Twelve patients discontinued the study because of protocol deviations (n = 3), AEs (n = 2), consent withdrawal (n = 2), concomitant pathology not linked to the study drug (n = 1), drop-out (n = 1) and other reasons (n = 3). The PP population comprised 291 patients (80.2% of the ITT population). The average duration of participation was 28.7 days. Adherence to study treatment was high at 96.4% of the expected intake, according to patients’ diaries.

Figure 1.

Patient flow.

ITT: intention to treat; PEG: polyethylene glycol; PP: per protocol.

There were no significant differences between groups in the general medical history, except for a tendency toward greater body mass index (p = 0.053) and more frequent sensation of anorectal obstruction (p = 0.054) in the lactulose plus paraffin group (Table 1). The mean duration of disease indicated long-standing constipation (duration >10 years). Forty-two per cent of the patients were taking at least one laxative in the month before study entry, with no difference between study groups notably regarding the investigated drugs. All of these drugs were stopped during the 14-day washout; only the rescue medication was allowed and was actually taken by more than 70% of the included patients.

Table 1.

Patients’ baseline characteristics (ITT population).

| Lactulose plus paraffin n = 179 | PEG n = 184 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 53.3 (18.1) | 52.9 (18.3) |

| Sex (n (%)) | ||

| Male | 53 (29.6) | 47 (25.5) |

| Female | 126 (70.4) | 137 (74.5) |

| Weight (kg) | 71.8 (13.8) | 68.6 (14.0) |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 26.0 (5.0) | 25.9 (4.8) |

| Physical exercise (n (%)) | 78 (43.6) | 90 (48.9) |

| Regularly | 41 (52.6) | 43 (47.8) |

| Occasionally | 37 (47.4) | 47 (52.2) |

| Relevant comorbidities (n (%)) | ||

| Gastritis | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.2) |

| Hypertension | 44 (24.6) | 35 (19.0) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 17 (9.5) | 15 (8.2) |

| Diabetes | 9 (5.0) | 11 (6.0) |

| Osteoarthritis | 12 (6.7) | 10 (5.4) |

| Depression | 13 (7.3) | 12 (6.5) |

| ≥2 Rome III criteria (n (%)) | 179 (100) | 184 (100) |

| Straining | 161 (89.9) | 172 (93.5) |

| Lumpy or hard stools | 159 (88.8) | 170 (92.4) |

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation | 128 (71.5) | 130 (70.7) |

| Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage | 81 (45.3) | 64 (34.8) |

| Manual manoeuvres | 27 (15.1) | 20 (10.9) |

| <3 SBMs per wk | 132 (73.7) | 145 (78.8) |

| Duration of constipation, y | 11.2 (14.8) | 11.8 (15.4) |

| Treatment for constipation during previous mo (n (%)) | 72 (40.2) | 82 (44.6) |

| SBM, number per wk | 4.1 (3.1) | 4.3 (3.1) |

| PAC-SYM score | 2.1 (0.4) | 2.1 (0.5) |

| Use of rescue medication during wash-out (n (%)) | 124 (72.1) | 135 (76.7) |

Data are presented as mean (SD) unless stated otherwise

BMI: body mass index; ITT: intention to treat; PAC-SYM: Patient Assessment of Constipation–Symptoms; PEG: polyethylene glycol; SBM: spontaneous bowel movement.

Efficacy

Primary end point

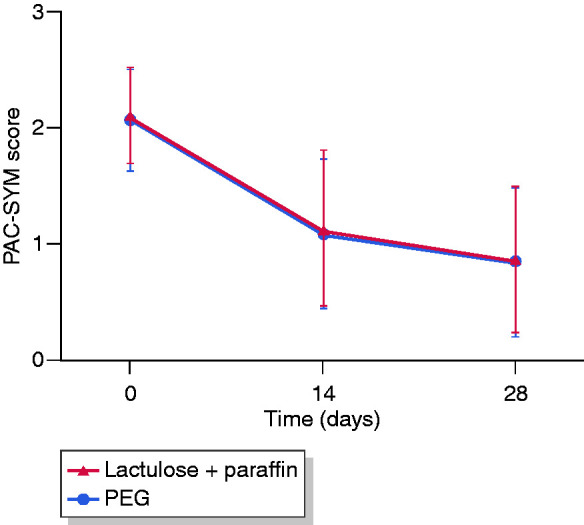

Mean PAC-SYM scores decreased from approximately 2.1 at baseline to 1.1 at day 14 and 0.9 at day 28 with both treatments (Figure 2). Change from baseline to day 14 and to day 28 was statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating a fast and sustained effect. The between-group difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) was −0.017 and the lower boundary of the 95% CI of the difference was −0.115, establishing the non-inferiority of lactulose plus paraffin vs PEG (Table 2). Analysis conducted using a mixed model for repeated measurements, with visit and baseline value as fixed covariates, demonstrated a highly significant (p < 0.001) effect of time and baseline values.

Figure 2.

Change in the PAC-SYM scores over time (PP population).

PAC-SYM: Patient Assessment of Constipation–Symptoms; PEG: polyethylene glycol; PP: per protocol.

Table 2.

Overall and subscale PAC-SYM scores (PP population).

| Lactulose plus paraffin n = 147 | PEG n = 144 | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall, mean (SD) score | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 2.1 (0.4) | 2.1 (0.4) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 0.9 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.7) |

| Change from baseline to end of treatment | −1.2 (0.0) | −1.2 (0.1) |

| Mean (95% CI) difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) | −0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) | |

| Abdominal symptoms, mean (SD) score | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.7) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 0.9 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.8) |

| Change from baseline to end of treatment | −1.1 (0.1) | −1.0 (0.1) |

| Mean (95% CI ) difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) | −0.1 (−0.1 to 0.2) | |

| Rectal symptoms, mean (SD) score | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.9) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.6) |

| Change from baseline to end of treatment | −0.9 (0.0) | −1.0 (0.0) |

| Mean (95% CI) difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.0) | |

| Stool symptoms, mean (SD) score | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.6) |

| End of treatment (Day 28) | 1.0 (0.8) | 0.0 (0.8) |

| Change from baseline to end of treatment | −1.6 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) |

| Mean (95% CI) difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) | −0.0 (−0.2 to 0.2) | |

CI: confidence interval; PAC-SYM: Patient Assessment of Constipation–Symptoms; PEG: polyethylene glycol; PP: per protocol.

The proportion of patients with a PAC-SYM change of 0.5 or greater was similar in both groups: 89.8% and 89.6% with lactulose plus paraffin and PEG, respectively. Sensitivity analysis conducted in the ITT population confirmed these results.

The non-inferiority of lactulose plus paraffin vs PEG was established for all three domains of PAC-SYM (Table 2). In both groups, baseline values (2.6 for both) and relative decreases at day 28 (approximately 60% of baseline values) were higher for stool symptoms than for abdominal and rectal symptoms.

Secondary efficacy end points

In both groups, the number of SBMs increased during the first two weeks of treatment from approximately 4 per week at day 0 to 6 per week at day 14, and then remained stable (Figure 3). The pattern of change was similar to that of the PAC-SYM score. Time effect was strong (p < 0.001), indicating a significant improvement with study treatment over time. On day 28, there was no difference between treatment groups in SBM frequency. The proportion of days with 1 or more SBMs increased to a similar extent in both groups, from 46.9% in the lactulose plus paraffin group and 48.7% in the PEG group at baseline, to 72.9% and 73.6%, respectively, at day 28. The proportion of patients with more than three SBMs per week at day 28 was 92.1% and 93.9%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Number of SBMs per week (PP population).

PEG: polyethylene glycol; SBM: spontaneous bowel movement.

The proportion of hard stools decreased from 59.4% and 59.9% at baseline to 24.3% and 20.7% at day 28 in the lactulose plus paraffin and PEG groups, respectively, and that of normal stools increased from 34.2% and 34.1% at baseline to 64.7% and 66.8% at day 28, respectively.

An improvement in the total and subscale PAC-QOL scores was observed in both treatment groups on day 28, with no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p > 0.05 for both, Table 3).

Table 3.

Overall and subscale PAC-QOL scores (PP population).

| Lactulose plus paraffin n = 146 | PEG n = 144 | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall, mean (SD) score | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 2.0 (0.6) | 2.0 (0.6) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.7) |

| Change from baseline to end of treatment | 0.9 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.1) |

| Mean (95% CI) difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) | |

| Physical discomfort, mean (SD) score | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.7) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.8) |

| Change from baseline to end of treatment | 1.2 (0.06) | 1.2 (0.1) |

| Mean (95% CI) difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) | |

| Psychosocial discomfort, mean (SD) score | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.8) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.8) |

| Change from baseline to end of treatment | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Mean (95% CI) difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.1) | |

| Worries and concerns, mean (SD) score | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.8) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 1.0 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.8) |

| Change from baseline to end of treatment | 0.8 ± 0.052 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Mean (95% CI) difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) | |

| Satisfaction, mean (SD) score | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.1 (0.8) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.0) |

| Change from baseline to end of treatment | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) |

| Mean (95% CI) difference (lactulose plus paraffin−PEG) | 0.0 (−0.2 to 0.3) | |

CI: confidence interval; PAC-QOL: Patient Assessment of Constipation–Quality of Life; PEG: polyethylene glycol; PP: per protocol.

In both groups, difficulties with defecation decreased dramatically under treatment (Table 4). Lactulose plus paraffin was significantly more effective than PEG in improving the feeling of discomfort during rectal evacuation (p = 0.048).

Table 4.

Problems with defecation (ITT population).

| Lactulose plus paraffin n = 179 | PEG n = 184 | |

|---|---|---|

| Straining | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 38.9 (34.3) | 42.4 (33.2) |

| Day 14 | 22.8 (28.9) | 21.0 (29.4) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 19.4 (29.0) | 22.1 (31.1) |

| P | 0.1583 | |

| Discomfort during evacuation | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 17.1 (26.2) | 16.88 (24.2) |

| Day 14 | 9.0 (18.0) | 9.33 (19.8) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 6.8 (17.0) | 8.58 (21.1) |

| P | 0.0478 | |

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 27.3 (29.9) | 31.6 (31.1) |

| Day 14 | 16.8 (26.9) | 21.1 (31.9) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 15.8 (27.2) | 18.1 (29.2) |

| P | 0.7164 | |

| Hard stools | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 29.1 (31.3) | 33.81 (33.6) |

| Day 14 | 13.7 (23.5) | 15.05 (25.2) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 10.0 (19.8) | 14.07 (24.5) |

| P | 0.5228 | |

| Long duration of evacuation | ||

| Baseline (day 0) | 18.2 (25.2) | 23.5 (29.7) |

| Day 14 | 9.8 (19.9) | 10.0 (21.0) |

| End of treatment (day 28) | 7.9 (17.2) | 11.8 (23.5) |

| P | 0.4822 | |

Data are presented as mean (SD) of the percentage of days during which the difficulty was reported. P values for treatment*time effect (mixed model for repeated measurements; analysis performed on raw (nontransformed) data with visit as fixed covariate.

ITT: intent-to-treat; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

Overall satisfaction of patients and physicians at the end of the study was high, without any statistical differences between treatment groups. PGIC was ‘better’ or ‘markedly better’ for 110 patients (62.8%) in the lactulose plus paraffin group and 100 patients (57.1%) in the PEG group. Treatment was judged as ‘effective’ or ‘very effective’ by 71.5% and 66.3% of investigators for lactulose plus paraffin and PEG, respectively.

Tolerability and safety

Twenty patients (11.2%) in the lactulose plus paraffin group and 26 patients (14.2%) in the PEG group reported 1 or more AEs. Most (>95%) AEs were of mild or moderate severity and unrelated to study drugs. The most frequent AEs with lactulose plus paraffin and PEG were diarrhoea (1.7% and 3.3%, respectively), abdominal distension (0.6% and 2.2%, respectively), nausea (1.7% and 1.1%, respectively), abdominal pain (2.2% and 0%, respectively) and dizziness (1.7% and 0%, respectively).

All AEs that were related to the study drug (lactulose plus paraffin: n = 3, 1.7%; PEG: n = 10, 5.5%) were gastrointestinal in nature, the most frequent being diarrhoea (0.6% and 3.0% respectively).

Two patients in the PEG group reported 1 or more serious AEs (both required hospitalisation); these AEs were not related to study treatment. Severe anaemia occurred in a 71-year-old man on anticoagulant treatment that resolved one day later. A mild depressive syndrome occurred in a 77-year-old woman with a history of depression and behavioural disorder, and was ongoing at the end of the study. The study drug was unchanged for both patients.

Three patients discontinued the study because of AEs. One patient in the lactulose plus paraffin group experienced spinal pain (not related to study treatment) and diarrhoea due to a painkiller. The other two patients were in the PEG group; one patient experienced episodes of gastroesophageal reflux, abdominal bloating and nausea, and the other patient had an episode of increased bloating (these AEs were all possibly treatment related).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to demonstrate the non-inferiority of lactulose plus paraffin vs PEG in the treatment of adult functional constipation. Baseline PAC-SYM scores were similar to those reported in the meta-analysis by Miller and colleagues22 and those reported in an observational study (mean score 1.6).23

The non-inferiority of lactulose plus paraffin to PEG was established and the change in the PAC-SYM score from baseline was greater than 1.2 points, which is markedly higher than the minimal clinically important difference of 0.5 determined by Yiannakou and colleagues.24 The robustness of this finding is supported by the sensitivity analysis conducted in the ITT population and by the analyses of the three subscales. Several other important evaluation parameters were also dramatically improved relative to baseline, for example, the number of stools increased from approximately four to six, the proportion of patients with three or more stools per week at day 28 was greater than 90% and the proportion of hard stools decreased by more than 50%.

Functional constipation is characterised by persistently difficult or seemingly incomplete defecation, and/or infrequent bowel movements (once every 3 to 4 days or less) in the absence of alarm symptoms or secondary causes.6 This definition, issued by the World Gastroenterology Organisation and adopted by the French National Society of Gastroenterology, emphasises the fact that assessment of constipation cannot rely on the number of stools per week alone, but must also consider the patient’s perspective.6 The European Medicines Agency (EMA) encourages the use of patient-reported outcome measures.25 For these reasons, this study used the PAC-SYM score as the primary evaluation criterion. PAC-SYM has been validated15,24,26 and used in more than 30 clinical studies and several meta-analyses.22,27

Although the analysis of correlation between the PAC-SYM score and stool frequency was not planned in the protocol, the pattern of change in both parameters over time was remarkably similar. This is consistent with the finding of the meta-analysis of 13 comparative studies, conducted by Shin and colleagues27 in which both the PAC-SYM score and the proportion of patients with three or more SBMs per week were significantly improved after treatment with 5-HT agonists relative to control, with a relative risk of 1.85 and 1.47, respectively.27 Further studies are needed to assess the statistical correlation between these two parameters.

A Cochrane meta-analysis that included 10 randomised controlled trials comparing lactulose with PEG in the management of chronic constipation reported that PEG was better than lactulose alone in improving the stool frequency and consistency, relieving abdominal pain and reducing the need for additional products.10 In our study a different galenic formulation was used, combining lower doses of lactulose and paraffin, for an equivalent laxative activity, resulting in a reduction in the related side effects of lactulose (bloating, gas and abdominal pain) when compared to a standard treatment with a 50% lactulose solution.28 Micronised particles of lactulose are coated with a protective paraffin layer (melting point of 35°C to 40°C) so that lactulose is gradually released in the colon as paraffin dissolves. Whereas lactulose increases the amount of water in the large bowel by osmolarity, paraffin provides lubrication and emulsification of the faecal mass, thus improving symptoms related both to proximal colonic transit and distal evacuation.

Some new pharmacological treatments of chronic constipation were recently investigated29: a) a 5-HT4 agonist such as prucalopride, tegaserod or velusetrag, b) the guanilate cyclase C receptor agonist linaclotide, c) the chloride channel type 2 opener lubiprostone, and finally d) an ileal bile acid transport inhibitor (elobixibat).

When studied in constipated patients, all these new drugs were concluded to be better than placebo in improving functional constipation.30 To date, they are not widely available, are usually much more expensive than older therapies, and some might have presented safety concerns.

To our knowledge, only one study has compared one of these new drugs, prucalopride, to PEG, leading to no difference in efficacy.31

One potential limitation of the present study is the absence of a double-blinding procedure. However, the masking procedure used was in line with the CONSORT and GRADE recommendations for limiting bias.13,14

Our study was designed for four weeks of treatment, preceded by a two-week washout period. This could be considered a relatively short duration; however, it is consistent with recent pivotal studies. Further investigations to assess the efficacy of laxatives on a long-term basis are warranted.

Another objective was to evaluate the impact of both treatments on QoL. In the present study, the overall PAC-QOL score was significantly improved at day 28 compared with baseline. All four domains were decreased, and the greatest improvement was observed in physical discomfort and patient satisfaction.

We observed a significant reduction in problems with defecation in patients receiving lactulose plus paraffin compared with PEG. These findings could be attributed to the beneficial effect of paraffin. The safety of both products was favourable, with an overall rate of AEs that was less than 15%, and with few AEs related to the study drug (lactulose plus paraffin: 1.7%; PEG: 5.5%). No new or unexpected safety signals were noted.

In conclusion, this study is the first to establish the non-inferiority of the combination of lactulose and paraffin vs PEG in functional constipation. Both treatments also increased the frequency of SBMs and improved patient QoL. Therefore, this combination of lactulose and paraffin, like other osmotic laxatives, may be used to treat functional constipation in adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Georgii Filatov, of Springer Healthcare Communications, for editing the manuscript before submission. The authors would like to acknowledge their co-investigator, Professor Philippe Ducrotté, who passed away in December 2017, for his help in making this study possible. Prof Ducrotté was fully involved in the conception of this study and he actively participated in the investigators’ meetings. Prof Ducrotté was one of the most well-recognised French gastroenterologists because of his major works on gastrointestinal motility and functional gastrointestinal pathologies. He was also a great mentor for many young gastroenterologists and a very friendly colleague in our international and national community.

Data for this work are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors have nothing to declare.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est 6 (ethics committee) 16 November 2015. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study design, data collection and analysis, and medical writing assistance were funded by Biocodex, France. Analysis and interpretation of the data were performed by M. Dapoigny and T. Piche, as well as validation of medical writing.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to initiating any procedures.

References

- 1.Suares NC, Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1582–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tack J, Muller-Lissner S, Stanghellini V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation – a European perspective. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 23: 697–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wald A, Scarpignato C, Kamm MA, et al. The burden of constipation on quality of life: Results of a multinational survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 26: 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piche T, Dapoigny M, Bouteloup C, et al. Recommandations pour la pratique clinique dans la prise en charge et le traitement de la constipation chronique de l’adulte: Recommendations for the clinical management and treatment of chronic constipation in adults. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2007; 31: 125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chassagne P, Ducrotte P, Garnier P, et al. Tolerance and long-term efficacy of polyethylene glycol 4000 (Forlax®) compared to lactulose in elderly patients with chronic constipation. J Nutr Health Aging 2017; 21: 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindberg G, Hamid SS, Malfertheiner P, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guideline: Constipation – a global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011; 45: 483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bharucha AE, Pemberton JH, Locke GR., 3rd. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. Gastroenterol 2013; 144: 218–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mion F. Conseil de pratique: Constipation, https://www.snfge.org/content/cp035-constipation (2018, accessed 7 November 2019).

- 9.Izzy M, Malieckal A, Little E, et al. Review of efficacy and safety of laxatives use in geriatrics. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016; 7: 334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee-Robichaud H, Thomas K, Morgan J, et al. Lactulose versus polyethylene glycol for chronic constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010: CD007570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laboratoires BIOCODEX. Examen du dossier de la spécialité inscrite pour une durée de cinq ans à compter du 2 février 2005. (JO du 20 mai 2005), https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2010-10/melaxose_-_ct-7108.pdf (1995, accessed 15 November 2019).

- 12.Norgine Limited. Movicol 13.8g sachet, powder for oral solution, https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1025/smpc (1995, accessed 15 November 2019).

- 13.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64: 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, et al. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA 2012; 308: 2594–2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank L, Kleinman L, Farup C, et al. Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999; 34: 870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, et al. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40: 540–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller-Lissner S, Rykx A, Kerstens R, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of prucalopride in elderly patients with chronic constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22: 991-998, e255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ke M, Zou D, Yuan Y, et al. Prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation in patients from the Asia-Pacific region: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012; 24: 999–e541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, et al. Clinical trial: The efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation – a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29: 315–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tack J, Stanghellini V, Dubois D, et al. Effect of prucalopride on symptoms of chronic constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014; 26: 21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Speed C, Heaven B, Adamson A, et al. LIFELAX – diet and LIFEstyle versus LAXatives in the management of chronic constipation in older people: randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 2010; 14: 1–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller LE, Ibarra A, Ouwehand AC. Normative values for colonic transit time and patient assessment of constipation in adults with functional constipation: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol 2017; 11: 1179552217729343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flourié B, Not D, François C, et al. Factors associated with impaired quality of life in French patients with chronic idiopathic constipation: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 28: 525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yiannakou Y, Tack J, Piessevaux H, et al. The PAC-SYM questionnaire for chronic constipation: Defining the minimal important difference. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 46: 1103–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on the evaluation of medicinal products for the treatment of chronic constipation (including opioid induced constipation) and for bowel cleansing, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-evaluation-medicinal-products-treatment-chronic-constipation-including-opioid-induced_en.pdf (2015, accessed 14 November 2019).

- 26.Lacy BE, Levenick JM, Crowell M. Chronic constipation: New diagnostic and treatment approaches. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2012; 5: 233–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin A, Camilleri M, Kolar G, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Highly selective 5-HT4 agonists (prucalopride, velusetrag or naronapride) in chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordin J, Berger M, Blatrix C, et al. Treatment of adult constipation with lactulose plus paraffin vs. 50% solution of lactulose. Méd Chir Dig 1997; 26: 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camilleri M. New treatment options for chronic constipation: Mechanisms, efficacy and safety. Can J Gastroenterol 2011; 25: 29B–35B. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson AD, Camilleri M, Chirapongsathorn S, et al. Comparison of efficacy of pharmacological treatments for chronic idiopathic constipation: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut 2017; 66: 1611–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cinca R, Chera D, Gruss HJ, et al. Randomised clinical trial: macrogol/PEG 3350+electrolytes versus prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation – a comparison in a controlled environment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 37: 876–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]