To the Editor:

We are writing with an update on mortality over time for our recent report, ICU and ventilator mortality among critically ill adults with COVID-19.[1] In our initial report of patients admitted from March 6 to April 17, 2020, hospital mortality was 30.9% (67/217) and mortality among those receiving mechanical ventilation was 35.7% (59/165).

ICU admissions and mortality

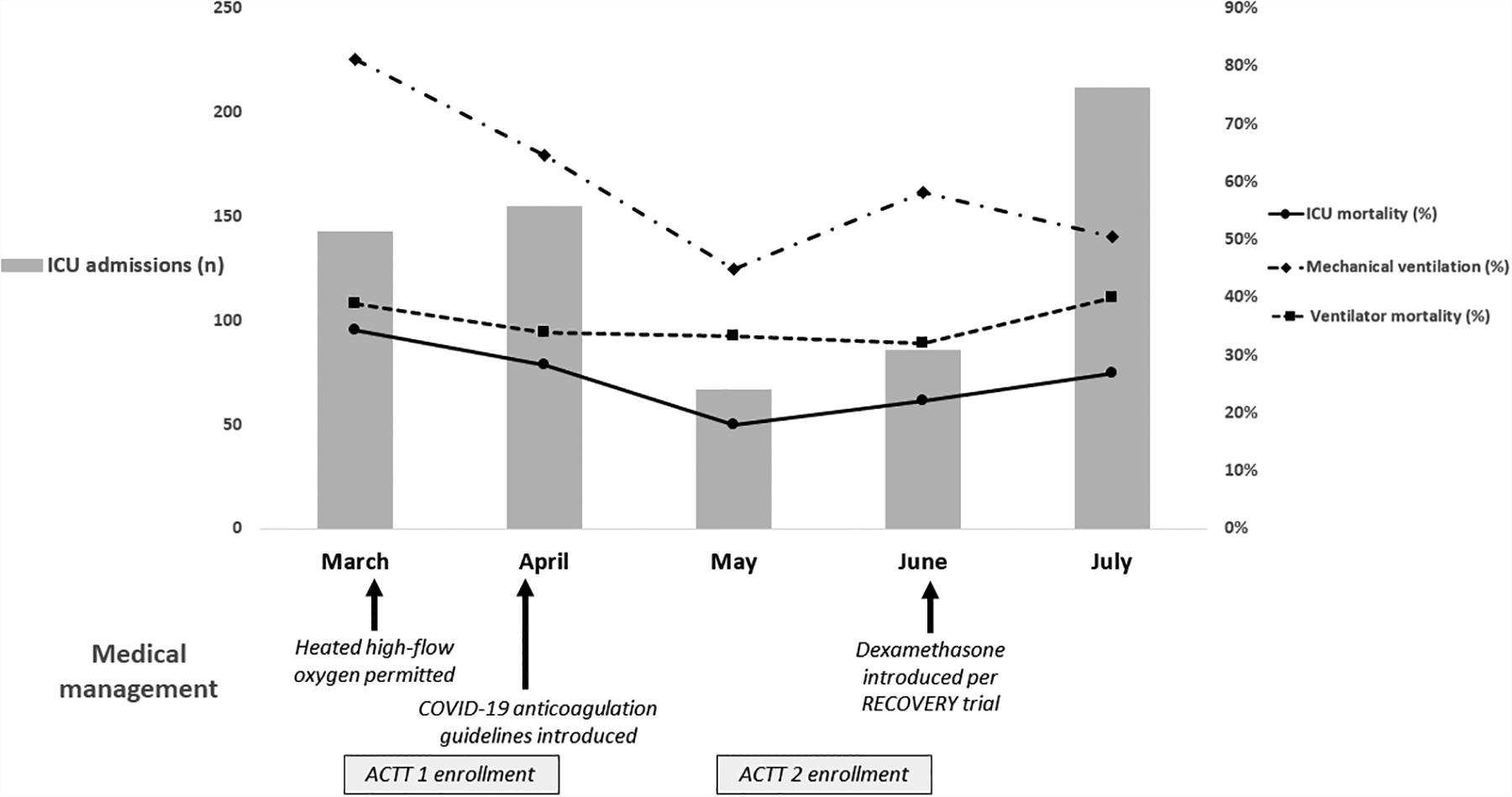

Since our earlier report, ICU admission numbers initially declined—from 143 patients in March and 155 in April to 67 in May and 86 in June—before increasing to 212 admissions in July (Figure, Table). This second wave of admissions in July did require the expansion of ICU capacity in order to accommodate critically ill patients with and without COVID-19. Nonetheless, and despite similar comorbidities and severity of illness throughout this time period (as measured by the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, initial Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, and PaO2/FiO2 ratio), hospital mortality declined from a peak of 34.3% in March, to 28.4% in April, 17.9% in May, 22.1% in June, and 26.8% in July.

Figure.

ICU admission numbers, changes in medical management, and patient outcomes over time for patients admitted to the ICU with COVID-19 from March to July, 2020.

Table.

Characteristics and clinical outcomes for patients admitted to a Coronavirus Disease-ICU from March to July, 2020.

| March | April | May | June | July | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # ICU admits | 143 | 155 | 67 | 86 | 212 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 65 (56–73) | 65 (54–76) | 61 (52–71) | 62 (49–73) | 62 (49–73) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 31 (27–36) | 30 (25–37) | 30 (25–37) | 29 (25–36) | 31 (27–38) |

| Black, n (%) | 103 (72.0) | 104 (67.1) | 37 (55.2) | 86 (61.6) | 147 (69.3) |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 7 (5–9) | 8 (6–10) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 6 (4–8) |

| Initial SOFA score, median (IQR) | 6 (5–7) | 7 (5–9) | 6 (5–8) | 7 (4–11) | 7 (4–11) |

| Initial P/F Ratio, median (IQR) | 164 (119–247) | 168 (123–262) | 168 (121–263) | 153 (103–243) | 132 (85–202) |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 116 (81.1) | 100 (64.5) | 30 (44.8) | 50 (58.1) | 107 (50.5) |

| Vent days, median (IQR) | 8 (4–13) | 11 (5–19) | 15 (6–23) | 9 (4–17) | 13 (8–25) |

| Vent deaths, n (%) | 45 (38.8) | 34 (34.0) | 10 (33.3) | 16 (32.0) | 25 (40.0) |

| Hospital LOS, median (IQR) | 14 (9–23) | 14 (9–24) | 13 (6–23) | 13 (7–21) | 13 (8–19) |

| Hospital deaths, n (%) | 49 (34.3) | 44 (28.4) | 12 (17.9) | 19 (22.1) | 30 (26.8) |

ICU = intensive care unit, BMI = body mass index, SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, P/F = PaO2/FiO2, LOS = length of stay.

Mechanical ventilation

The proportion of patients receiving mechanical ventilation also declined, from a peak of 81.1% in March, to 64.5% in April, 44.8% in May, 58.1% in June, and 50.5% in July. However, ventilator mortality remained relatively stable between 32–40% throughout the five-month period. Of note, our institution did not support the use of heated high-flow oxygen until March 25th, which likely contributed to higher intubation rates in March.

Medical management

Our ICU care and treatments also changed over time. In early April our institution introduced a COVID-specific anticoagulation strategy with an intermediate level of prophylaxis for a D-dimer ≥3,000 ng/ml. While analyses on the impact of this strategy are underway, published reports suggest a survival benefit with anticoagulation in COVID-19.[2, 3] Our institution was also a study site for ACTT1 and ACTT2. From March 11 to April 19, 96 patients enrolled in ACTT1 and, from May 8 to June 30, 77 patients enrolled in ACTT2. Although ACTT1 did not show a benefit for remdesivir in patients requiring high-flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation,[4] ACTT2 results are pending and it is possible that the combination of remdesivir and baracitinib (which approximately half of patients would have received) could have contributed to the improved mortality in May and June. Likewise, after the RECOVERY trial data were made available in mid-June,[5] 45/86 (52%) and 177/212 (83%) patients received dexamethasone in June and July, respectively, of whom 31 (68.9%) and 137 (77%) survived.

We are gratified to report these improvements in mortality over time, which echo the findings of a recent meta-analysis and published data from the United Kingdom.[6, 7] These declines in mortality likely reflect improvements in our provision of critical care as we have gained experience with this novel pathogen. Our medical management is also now supported by findings from a small, but growing, number of randomized clinical trials. However, the rapidly changing landscape of COVID-19, both in terms of local case numbers and the evidence base for clinical care, underscores the importance of continuing to assess outcomes so that we can better understand how best to care for our patients.

Footnotes

Copyright form disclosure: Dr. Auld received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Sara C. Auld, Emory Critical Care Center, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, Department of Epidemiology, Emory University.

Mark Caridi-Scheible, Emory Critical Care Center, Department of Anesthesiology, Emory University.

Chad Robichaux, Department of Biomedical Informatics, Emory University, and Georgia Clinical and Translational Science Alliance (CTSA).

Craig M. Coopersmith, Emory Critical Care Center, Department of Surgery, Emory University.

David J. Murphy, Emory Critical Care Center, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, Emory University, Office of Quality and Risk, Emory Healthcare.

References

- 1.Auld SC, Caridi-Scheible M, Blum JM, Robichaux C, Kraft C, Jacob JT, Jabaley CS, Carpenter D, Kaplow R, Hernandez-Romieu AC et al. : ICU and Ventilator Mortality Among Critically Ill Adults With Coronavirus Disease 2019. Crit Care Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paranjpe I, Fuster V, Lala A, Russak AJ, Glicksberg BS, Levin MA, Charney AW, Narula J, Fayad ZA, Bagiella E et al. : Association of Treatment Dose Anticoagulation With In-Hospital Survival Among Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 76(1):122–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z: Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18(5):1094–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, Hohmann E, Chu HY, Luetkemeyer A, Kline S et al. : Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Normand S-LT: The RECOVERY Platform. New England Journal of Medicine 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong RA, Kane AD, Cook TM: Outcomes from intensive care in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Anaesthesia 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ICNARC report on COVID-19 in critical care [https://www.icnarc.org/About/Latest-News/2020/04/04/Report-On-2249-Patients-Critically-Ill-With-Covid-19]