Abstract

Background

Emerging findings have increased concern that exposure to fine particulate matter air pollution (aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm; PM2.5) may be neurotoxic, even at lower levels of exposure. Yet, additional studies are needed to determine if exposure to current PM2.5 levels may be linked to hemispheric and regional patterns of brain development in children across the United States.

Objectives

We examined the cross-sectional associations between geocoded measures of concurrent annual average outdoor PM2.5 exposure, regional- and hemisphere-specific differences in brain morphometry and cognition in 10,343 9- and 10- year-old children.

Methods

High-resolution structural T1-weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and NIH Toolbox measures of cognition were collected from children at ages 9–10 years. FreeSurfer was used to quantify cortical surface area, cortical thickness, as well as subcortical and cerebellum volumes in each hemisphere. PM2.5 concentrations were estimated using an ensemble-based model approach and assigned to each child’s primary residential address collected at the study visit. We used mixed-effects models to examine regional- and hemispheric- effects of PM2.5 exposure on brain estimates and cognition after considering nesting of participants by familial relationships and study site, adjustment for socio-demographic factors and multiple comparisons.

Results

Annual residential PM2.5 exposure (7.63 ± 1.57 μg/m3) was associated with hemispheric specific differences in gray matter across cortical regions of the frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes as well as subcortical and cerebellum brain regions. There were hemispheric-specific associations between PM2.5 exposures and cortical surface area in 9/31 regions; cortical thickness in 22/27 regions; and volumes of the thalamus, pallidum, and nucleus accumbens. We found neither significant associations between PM2.5 and task performance on individual measures of neurocognition nor evidence that sex moderated the observed associations.

Discussion

Even at relatively low-levels, current PM2.5 exposure across the U.S. may be an important environmental factor influencing patterns of structural brain development in childhood. Prospective follow-up of this cohort will help determine how current levels of PM2.5 exposure may affect brain development and subsequent risk for cognitive and emotional problems across adolescence.

Keywords: fine particulate matter, MRI, neurodevelopment, cortical thickness, brain, cognition

1. Introduction

Ambient fine particulate matter (aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm; PM2.5) is a ubiquitous criteria air pollutant and environmental neurotoxin (Brockmeyer & D’Angiulli, 2016; Cohen et al., 2017). PM2.5 particles are small enough to infiltrate the lower respiratory tract, and as shown in experimental studies, cause oxidative stress, systemic inflammation and toxic effects on the nervous system and the brain (Block et al., 2012; Thomson, 2019; Woodward et al., 2017; World Health Organization, 2013). Recent evidence from epidemiological studies also indicates that PM2.5 exposure may be especially harmful to children, as the brain continues to develop across childhood and into the third decade of life (Block et al., 2012; Clifford, Lang, Chen, Anstey, & Seaton, 2016; Costa et al., 2017; de Prado Bert, Mercader, Pujol, Sunyer, & Mortamais, 2018; Sram, Veleminsky, Veleminsky, & Stejskalova, 2017). Exposure to PM2.5 and its constituents have been linked with adverse neurobehavioral effects during childhood and adolescence, including reduced intelligence (IQ) (Chiu et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2010; Perera et al., 2009; Porta et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017) and impairment in cognitive function (Chiu et al., 2016; Sunyer et al., 2015; Sunyer et al., 2017). These adverse behavioral effects suggest PM2.5 may impact distinct patterns of brain development, especially given that improvements in cognitive functioning parallel regional and hemispheric cortical and subcortical gray matter neuromaturation across childhood and adolescence (Casey, Tottenham, Liston, & Durston, 2005; Giedd et al., 1999; Gogtay et al., 2004; Herting et al., 2018; Shaw et al., 2006; Sowell, Delis, Stiles, & Jernigan, 2001; Sowell et al., 2003; Sowell et al., 2004; Tamnes et al., 2017) and functional specialization of brain regions (Gazzaniga, 1995; Gotts et al., 2013; Kong et al., 2018; Mesulam, 1990; Nagel, Herting, Maxwell, Bruno, & Fair, 2013).

Human in vivo neuroimaging studies have begun to examine how PM2.5 exposure may influence brain development, but the results have been inconsistent and very little attention has been directed to hemispheric and regional specificity in the brain structures potentially affected by air pollution neurotoxicity. Specifically, patterns of brain maturation occur in a posterior-to-anterior and inferior-to-superior fashion, with sensory and motor cortices developing earlier (Sowell 2004, Giedd 1999), while prefrontal and limbic regions (e.g., amygdala, hippocampus) continue to undergo considerable maturation during adolescence (Giedd 1999, Herting 2018). In addition, cortical areas respond to specific stimuli and are involved in distinct mental processes (Afifi & Bergman, 2005). As such, hemispheric specialization exists for a number of cognitive functions that continue to develop across childhood and adolescence, such as language (Purves et al., 2001), working memory (Nagel et al., 2013) and relational reasoning (Vendetti, Johnson, Lemos, & Bunge, 2015). Because the human brain is comprised of highly specialized components (Kanwisher, 2010), understanding hemispheric and regional specificity of PM2.5 exposure may help elucidate the neural circuits most vulnerable to exposure across child and adolescent development. While associations with global brain volumes have not been observed, previous studies provide preliminary evidence for regional and hemispheric specificity of differences in brain development related to PM2.5 exposure (Beckwith et al., 2020; Guxens et al., 2018; Mortamais et al., 2017; Peterson et al., 2015; Pujol et al., 2016b; Pujol et al., 2016a). For example, higher prenatal PM2.5 exposure in Rotterdam, Netherlands, was related to reduced cortical thickness in the right prefrontal cortex at ages 6–10 years (N=783), while no associations were seen for the left hemishere (Guxens et al., 2018). Reduced cortical thickness, with regional and hemispheric differences noted in the posterior frontal and anterior parietal lobes, were also found in 12 year-old children from Cincinnati, Ohio who were exposed to high traffic-related air pollution during their first postnatal year of life (N=135) (Beckwith et al., 2020). In Barcelona, Spain, increased gray matter density within the basal ganglia in 8–12 year-olds was associated with exposure to PM2.5 components (elemental carbon (EC), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), copper) at the time of testing (N=263) (Mortamais et al., 2017; Pujol et al., 2016b; Pujol et al., 2016a). Two other studies, however, found no associations of cortical gray matter thickness with either prenatal exposure (N=40, ages 7–9 years (Peterson et al., 2015)) or recent exposure (N=263, ages 8–10 (Pujol et al., 2016a)) to PM2.5 constituents. However, these studies have had small sample sizes and limited geographical coverage; potentially limiting generalizability of findings to children in cities across the United States.

In the current study, we aimed to examine how annual PM2.5 exposure relates to gray matter morphology in 10,343 9 to 10-year-olds enrolled in Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. We utilized a novel hybrid model to estimate residential PM2.5 exposure at the time of the study visit and further accounted for geographic, demographic, and socioeconomic diversity at 21 research sites throughout the United States (Compton, Dowling, & Garavan, 2019; Garavan et al., 2018; Jernigan, Brown, & Dowling, 2018; Volkow et al., 2018). Cortical volume is a composite score that reflects both cortical thickness and surface area, with known differences in the developmental trajectories of cortical volume, thickness, and surface area across various brain regions (Raznahan et al., 2011). Moreover, gray matter morphometric properties are not genetically linked (Rakic, 2009); rather cortical thickness and surface area capture distinct biological processes (Raznahan et al., 2011) and should be considered separately in understanding how PM2.5 exposure may impact brain development. Therefore, we hypothesized that higher PM2.5 exposure would be associated with widespread differences in gray matter morphology as well as distinct regional- and hemispheric- specificity. We also hypothesized higher exposure PM2.5 levels would be associated with worse cognitive performance, particularly for measures of general intelligence.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

We obtained baseline data from the 2019 NDA 2.0.1 data release of the ABCD study, which includes in total 11,8705 9–10 year-olds (Garavan et al., 2018; Jernigan et al., 2018; Volkow et al., 2018). Participants were assessed at 21 study sites across the United States. Sample recruitment at these sites and other information about the ACBD study have been reported previously in detail (Bagot et al., 2018; Barch et al., 2018; Casey et al., 2018; Feldstein Ewing et al., 2018; Garavan et al., 2018; Hagler et al., 2018; Luciana et al., 2018; Uban et al., 2018). A schematic overview of the study is available in Supplementary Material (SFig. 1). Briefly, inclusion criteria for the ABCD study were as follows: 1) age 9.00 to 10.99 years at the time of baseline assessment; 2) able to validly and safely complete the baseline visit including MRI; 3) Fluent in English. Child and caregiver participants completed an in-person baseline visit between October 2016 and October 2018 in which residential address and brain scans were collected. Annual average PM2.5 exposure levels estimated for 2016 were assigned to each participant’s primary residential address at the time of the study visit. Details of exclusionary criteria are presented in Supplementary Material. Centralized institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the University of California, San Diego. Study sites obtained approval from their local IRBs. Written informed consent was provided by each parent or caregiver; each child provided written assent. All ethical regulations were complied with during data collection and analysis. An identical protocol was utilized for recruitment, neuropsychological assessment, and neuroimaging of all participants in the ABCD study (Auchter et al., 2018). Our analytic sample was limited to participants with 1) an estimate of PM2.5 exposure in microgram per m3 (μg/m3) at the 1-km2 grid assigned to the primary residence address collected at the time of the study visit, 2) complete data on major sociodemographic characteristics, including age, sex, race/ethnicity and family socioeconomic status, and 3) either complete NIH Cognitive Toolbox scores and/or high-quality T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Missingness in covariates was minimal (N=183), therefore multiple imputations were not performed, rather these individuals were excluded from the study. A total of 10,343 subjects were retained in the MRI analyses, whereas 10,127 subjects were included in the cognitive analyses (SFig. 2).

2.2. MRI Acquisition and Preprocessing

ABCD MRI methods and assessments have been optimized and harmonized across the 21 sites for 3 Tesla scanners (Siemens Prisma, General Electric 750, Philips) (Casey et al., 2018; Hagler et al., 2018). Cortical surface reconstruction and subcortical segmentation was completed via FreeSurfer (version 5.3), including total gray and white matter as well as subcortical volumes, cortical thickness and cortical surface area estimates for cortical regions using the Desikan-Killiany Atlas (Dale, Fischl, & Sereno, 1999; Hagler et al., 2018). At the central ABCD Data Analysis and Informatics Center (DAIC), T1-weighted structural images underwent quality control (QC) across five categories, both prior to and after post-processing to gauge the severity of motion, intensity inhomogeneity, white matter underestimation, pial overestimation, and magnetic susceptibility artifact (Hagler et al., 2018). Only image types passing QC for all categories were included in our analyses (SFig. 2). Subjects lost after MRI QA/QC (n=644) were significantly younger (age in months: 117.7 ± 7.3; p<0.0001) but did not significantly differ by sex (53.6% male; p=0.53) from the rest of the cohort.

2.3. Estimation of fine particulate matter exposure

We used daily estimates of state-of-the-art hybrid spatiotemporal PM2.5 models to aggregate annual PM2.5 exposure levels with 1-km2 resolution and to assign them to each participant’s home addresses at the time of the baseline visit (Di et al., 2019). Each child’s primary residential address was collected from the participant’s caregiver during the study visit and geocoded by the DAIC using the google map API to generate latitude and longitude (Google Maps Platform Documentation, 2019). Daily PM2.5 concentrations were obtained for the 2016 calendar year using an ensemble-based model approach (Di et al., 2019) that combines the strengths of satellite-based aerosol optical depth (AOD) models, land-use regression, and chemical transport models (CTM). This spatiotemporal modeling approach also incorporated the input of normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), surface reflectance, absorbing aerosol index, elevation, road density, emission inventory, population density, percentage urban land, meteorological parameters, and other spatial covariates. To account for complex atmospheric mechanisms, a neural network, a random forest, and gradient boosting were used for their capacity to model nonlinearity and interactions, and then ensemble averaged with a geographically weighted regression. The model for the continental United States from 2000 to 2016 has been trained and tested with left out monitors, with ten-fold cross-validation (CV) for daily predictions showing a high R2 of 0.86 on the left-out monitors; for annual average exposure, CV R2 was 0.89. Annual average 2016 calendar year estimates were then aggregated and assigned to the geocoded baseline residential locations of ABCD participants by the DAIC.

2.4. Covariates

Selection of potential confounders was based on both prior knowledge and empirical data (Weng, Hsueh, Messam, & Hertz-Picciotto, 2009). A directed acyclic graph (DAG) (Greenland & Brumback, 2002) was used to identify confounders that may predict neurobehavioral development and exposure to ambient air pollutants (SFig. 3). The following covariates were included in the main analysis: child’s age, familial relationships, caregiver’s report of the child’s sex at birth, race/ethnicity, parental higher education (of any household member), total combined family income, parental employment status, handedness and the imaging device manufacturer. We also included an average score of three-items assessing parent perspectives of how safe and free from crime their neighborhood is (Mujahid, Diez Roux, Morenoff, & Raghunathan, 2007). For subcortical volume analyses, intracranial volumes (ICV) were also included as a covariate. The ABCD Data Exploration and Analysis and Exploration Portal (DEAP) variable definitions were used for race and ethnicity and for parental higher education. Details about the remaining covariate measurements and selection of additional covariates are available in Supplementary Material (STable 1).

PM2.5 exposure estimates capture both local and regional sources of air pollution, and the urban built environment is likely to impact PM2.5 exposure. In sensitivity analyses we assessed additional confounding effects of population density and distance to road (STable 2), and we explored heterogeneity of PM2.5 effects by ABCD site. Specifically, residentially derived United Nations population density was measured as persons per km2 (based on population counts of the 2010 national census tract adjusted for potential underreporting across the world) (Center for International Earth Science Information Network - CIESIN - Columbia University, 2016) as a proxy for urbanicity. Distance to major roads and highways in meters (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2017) was treated as a categorical variable reflecting those living <150, 150–300m, 300–600m, or > 600m based on previous studies showing that near-roadway pollutants decay to background levels by approximately 115–570m (Karner, Eisinger, & Niemeier, 2010).

2.5. Neurocognitive performance

The ABCD study neurocognitive session at the baseline visit included the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (NIHT) (Heaton et al., 2014; Luciana et al., 2018; Weintraub et al., 2014). Each child completed the List Sorting Working Memory Test, Flanker Attention Test, Dimensional Card Sorting Task, Picture Vocabulary Test, Oral Reading Recognition Test, Picture Sequence Memory Test, and Pattern Comparison Processing Speed Test. Using performance on these 7 items, composite scores include a total cognitive score, as well as crystalized and fluid cognitive function score (Gershon et al., 2013). Given our models included demographic variables, unstandardized scores were utilized as the primary dependent variables of cognition.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R software (version 3.5.2). We first examined differences in covariate information across PM2.5 quintiles using Pearson’s Chi-square test for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Next, we implemented multilevel mixed effects modeling to examine the association between annual PM2.5 exposure and structural brain or neurocognitive performance outcomes of interest. Based on recent evidence showing regional- and hemisphere- specific differences in surface area and cortical thickness in the general population (Kong et al., 2018) as well as in relation to PM2.5 (Guxens et al., 2018; Peterson et al., 2015) we examined the main effect of PM2.5 and a cross-product term of PM2.5 by hemisphere (i.e. interaction, see equation (1)), to determine if the association between PM2.5 and brain morphology differed by hemisphere, in 31 regions of surface area and 27 regions of cortical thickness. Previous research has showed subcortical volumes may also be associated with annual PM2.5 related exposure during childhood (Pujol et al., 2016b), therefore we also examined 8 subcortical regions including cerebellum volumes. We included a random effect for ABCD site (j) and a nested random effect for family (k) within ABCD site for participant i so as to account for between-site variability and within-family correlations. A nested random intercept for subject (i) was also added to the model to account for the hemisphere related within-subject variability. At the first stage of the analysis we used generalized additive mixed effect models (GAMMs) to explore the shape of the association between PM2.5 and outcomes under study. Significant deviations from linearity were not detected, so we proceeded with a linear modeling strategy. Our final modeling equation was:

| (1) |

Next, we employed a two-level linear mixed-effects model to examine the association of annual residential PM2.5 exposure with whole brain estimates (total surface area, total cortical thickness, total gray and total white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, intracranial volume, and ventricle volumes). We included a random effect for ABCD site (j) and a nested random effect for family (k) within ABCD site for participant i, as presented in the following equation:

| (2) |

In all analyses, we scaled the effect estimates for PM2.5 to 5 μg/m3. This increment has been widely used in previous research assessing health effects of PM2.5, including brain and cognitive development, thus allowing direct comparability of previous results with ours (Beelen et al., 2014; Guxens et al., 2014; Guxens et al., 2018). Regional and hemispheric analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons using a false discovery rate correction and a 0.05 level of significance. To interpret PM2.5 and brain metrics in regions with significant interactions, individual regression models were fit for each hemisphere separately to illustrate the difference in the associations with PM2.5 by hemisphere interactions (Robinson, 2013). Finally, we also employed the two-level linear mixed-effects model presented in equation (2) to examine the association of PM2.5 exposure with each of the 7 NIH Cognitive Toolbox outcomes and the 3 composite scores. We also examined the potential effect moderation by sex through stratified analyses, as previous studies have suggested sex-specific effects of PM2.5 (Costa et al., 2017; Kern et al., 2017). In follow-up sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for population density and distance to road, and explored heterogeneity of PM2.5 effects by site by including a random slope of PM2.5 by site.

Results

3.1. Study population and exposure distribution

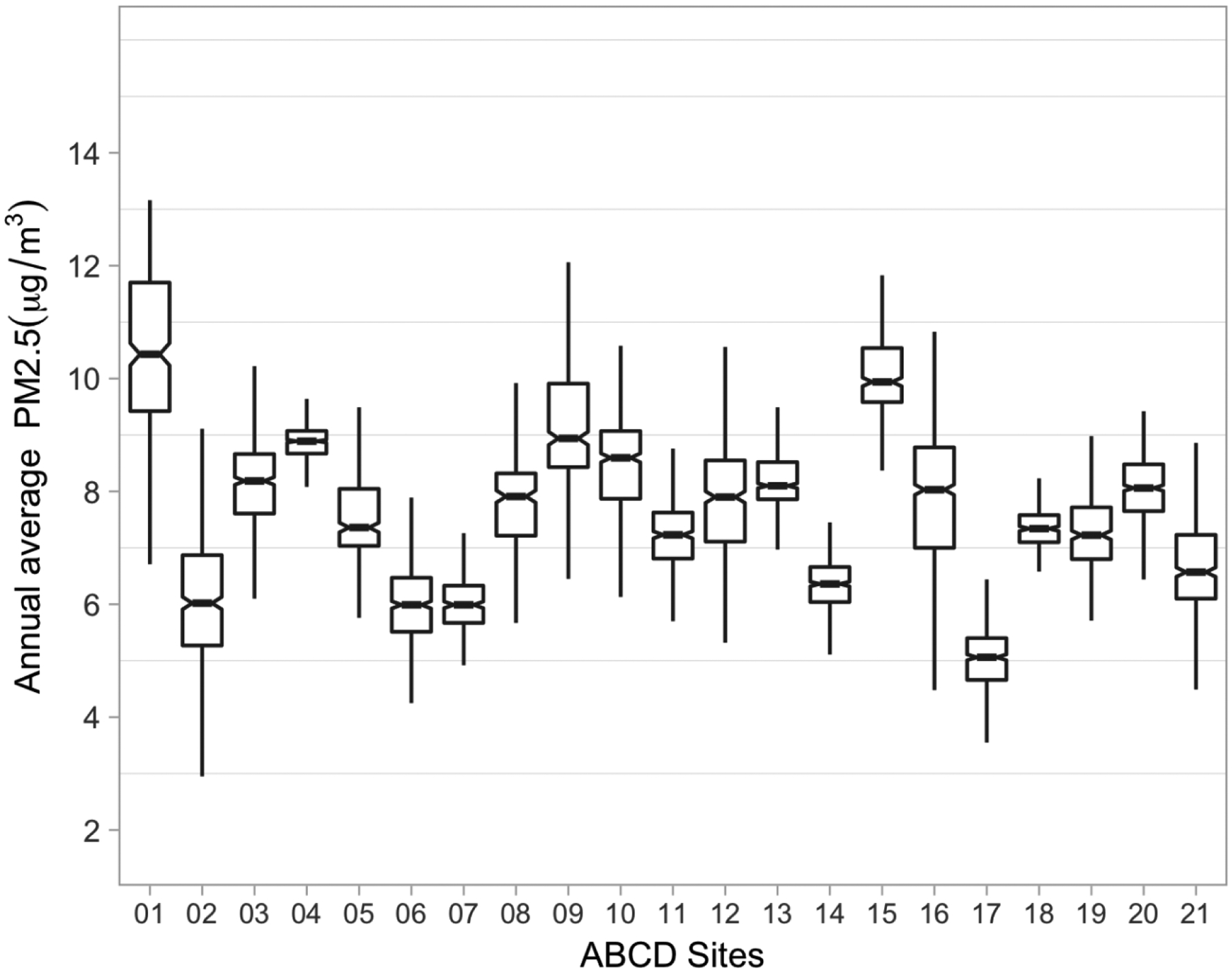

Substantial variability was seen in annual PM2.5 exposures both within and between the 21 ABCD study sites, with median PM2.5 concentrations ranging from 5.1 μg/m3 (Site 17, min=2.4 μg/m3, max=9.3 μg/m3) to 10.4 μg/m3 (Site 01, min=1.7 μg/m3, max=13.2 μg/m3) and overall distribution ranging from 1.72 – 15.9 μg/m3 (Fig. 1, Table 1). The distribution of annual PM2.5 exposures was associated with both demographic and social covariates (Table S2). Participants with relatively high exposure in the upper two quintiles (>8.45 μg/m3) were more likely to be ethnic minorities (Hispanic or Black), to have parents with a lower level of education, and to come from families earning less than $49,999 in total family income over the past 12 months (Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of baseline annual PM2.5 average (based on daily estimates at the primary residential location) by ABCD study site (N=10,343) in the ABCD Study.

Footnote: The line within the box marks the median; the boundaries of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; horizontal bars denote the variability outside the upper and lower quartiles (ie, within 1.5 IQR of the lower and upper quartiles).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study sample (N=10,343) in the ABCD Study.

| Characteristics of study sample (N=10, 343) | |

|---|---|

| Age (months): mean ± SD (range) | 119.1 ± 7.7 (108–131) |

| Familial relationship | |

| Single: N (%) | 7179 (69.4%) |

| Sibling: N (%) | 1368 (13.2%) |

| Twin: N (%) | 1769 (17.1%) |

| Triplet: N (%) | 27 (0.3%) |

| Sex | |

| Female: N (%) | 4933 (47.7%) |

| Male: N (%) | 5410 (52.3%) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Asian: N (%) | 212 (2.1%) |

| Black: N (%) | 1461 (14.1%) |

| Hispanic: N (%) | 2111 (20.4%) |

| Other: N (%) | 1025 (9.9%) |

| White: N (%) | 5534 (53.5%) |

| Parental higher education | |

| ≤HS diploma/GED: N (%) | 1426 (13.8%) |

| Some college: N (%) | 2682 (25.9%) |

| Bachelor: N (%) | 2663 (25.7%) |

| Post Graduate: N (%) | 3572 (34.5%) |

| Total family income | |

| <$5,000: N (%) | 337 (3.3%) |

| $5,000 – $11,999: N (%) | 359 (3.5%) |

| $12,000 – $15,999: N (%) | 237 (2.3%) |

| $16,000 – $24,999: N (%) | 430 (4.2%) |

| $25,000 – $34,999: N (%) | 571 (5.5%) |

| $35,000 – $49,999: N (%) | 803 (7.8%) |

| $50,000 – $74,999: N (%) | 1329 (12.8%) |

| $75,000 – $99,999: N (%) | 1401 (13.5%) |

| $100,000 – $199,999: N (%) | 2942 (28.4%) |

| > $200,000: N (%) | 1094 (10.6%) |

| Unknown: N (%) | 840 (8.1%) |

| Parental employment status | |

| Working: N (%) | 7187 (69.5%) |

| Unemployed: N (%) | 73 (0.7%) |

| Temporarily Laid off: N (%) | 71 (0.7%) |

| Looking for work: N (%) | 411 (4.0%) |

| Sick Leave: N (%) | 17 (0.2%) |

| Stay at Home Parent: N (%) | 1826 (17.7%) |

| Maternity Leave: N (%) | 26 (0.3%) |

| Retired: N (%) | 65 (0.6%) |

| Student: N (%) | 200 (1.9%) |

| Disabled: N (%) | 213 (2.1%) |

| Other: N (%) | 207 (2.0%) |

| Unknown: N (%) | 47 (0.5%) |

| Handedness | |

| Left: N (%) | 1145 (11.1%) |

| Right: N (%) | 9157 (88.5%) |

| Both: N (%) | 41 (0.4%) |

| MRI manufacturer | |

| Ge Medical Systems: N (%) | 2415 (23.3%) |

| Philips Medical Systems: N (%) | 1205 (11.7%) |

| Siemens: N (%) | 6723 (65.0%) |

| Neighborhood quality: mean ± SD (range) | 3.9± 0.97 (1–5) |

| Annual average PM2.5 (μg/m3) mean ± SD (range) | 7.63 ± 1.57 (1.72–15.9) |

2.2. Links between residential PM2.5 exposure levels and cortical brain structure

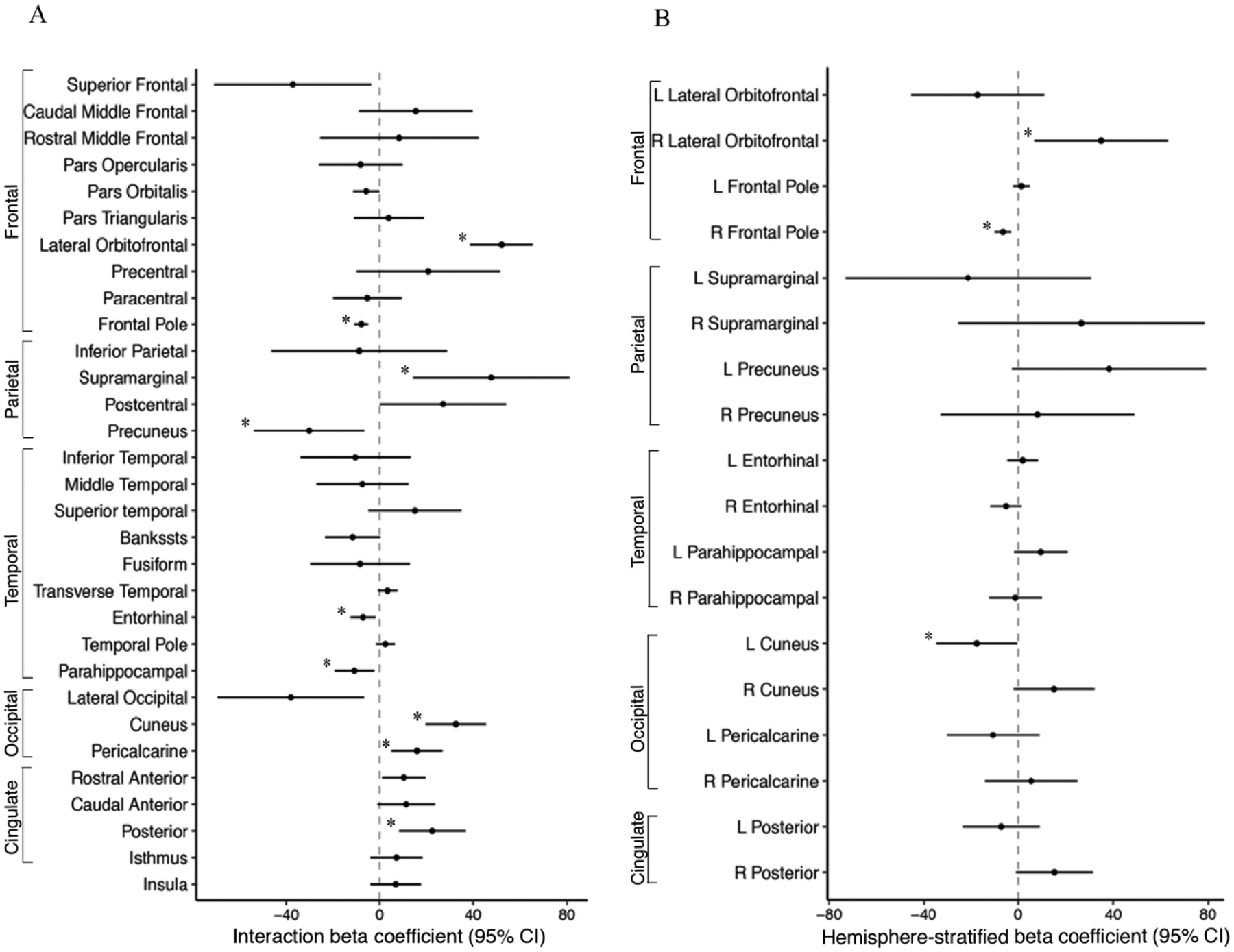

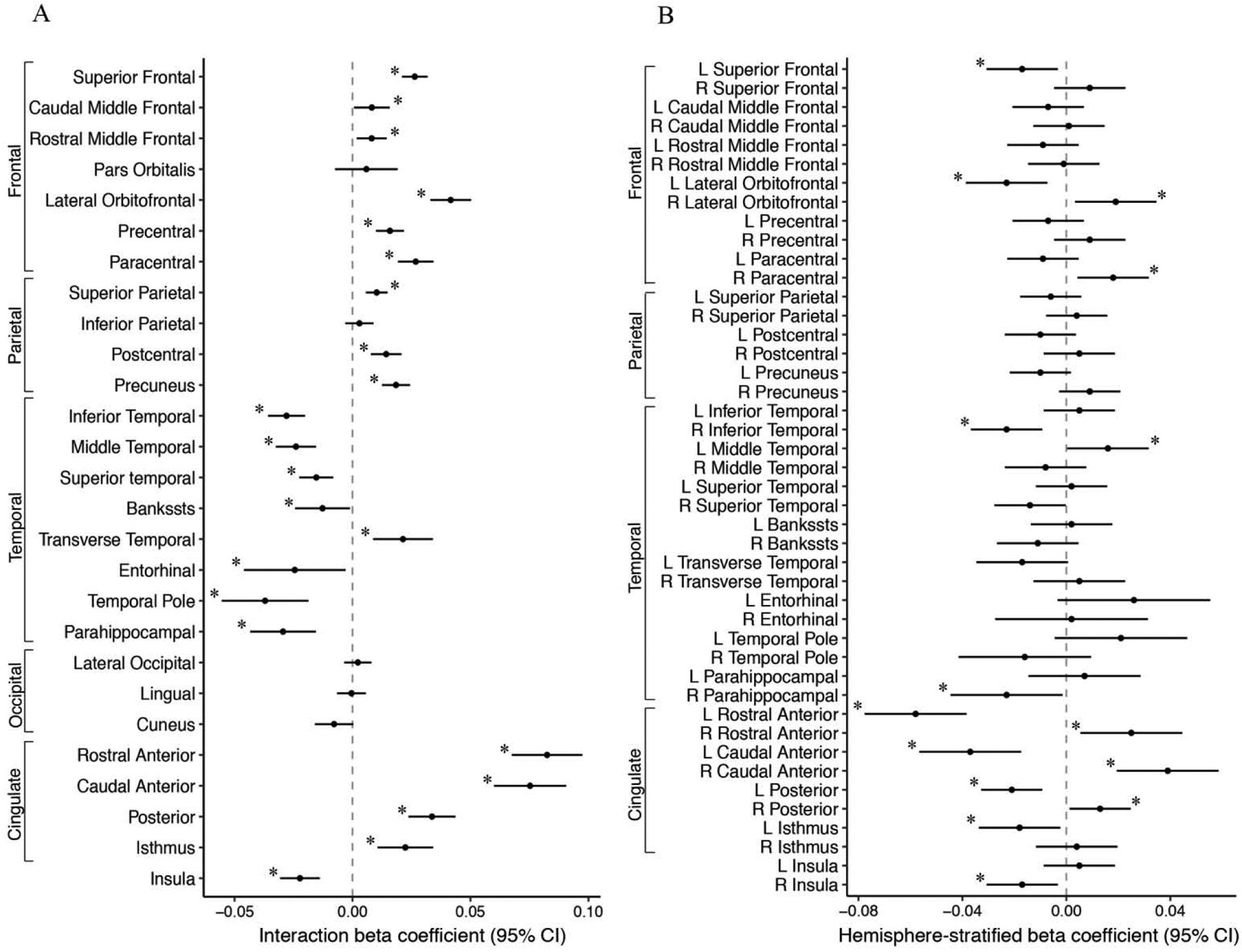

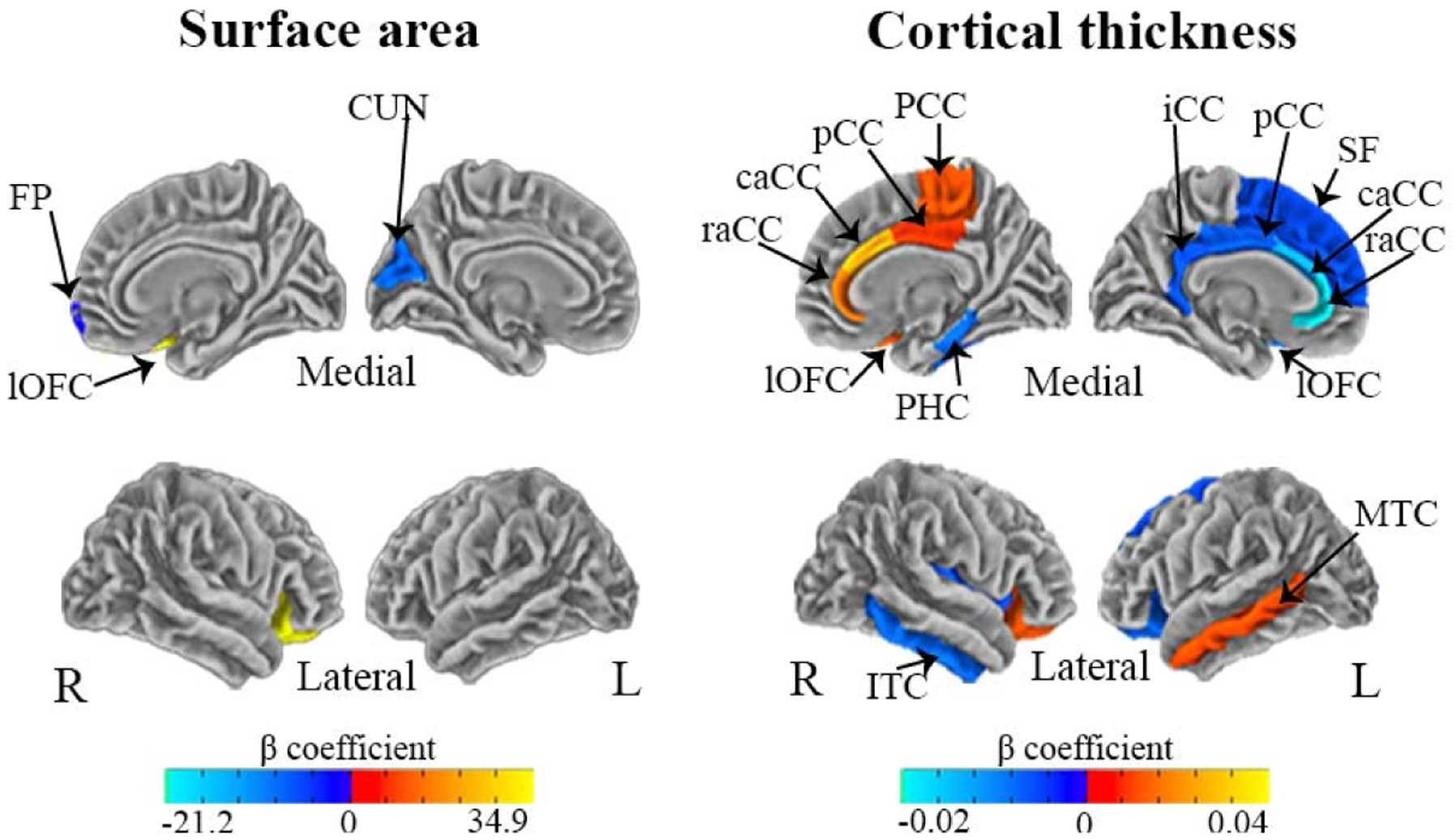

Increased PM2.5 exposure was associated with hemispheric-specific differences in surface area and cortical thickness in regions of the frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital and cingulate lobes (FDR corrected, p<0.05). Specifically, we observed hemispheric differences (i.e. significant PM2.5 - hemisphere interaction) in the association of PM2.5 with surface area for 9/31 regions (29%) (Figure 2 A) and 22/27 (81%) cortical thickness regions examined (Figure 3A). Results from regional effect estimates stratified by hemisphere revealed positive associations between PM2.5 in some regions and negative associations in others. For surface area, an increase of 5-μg/m3 in PM2.5 exposure was associated with 17.5 mm2 smaller surface area in the left cuneus and 6.5 mm2 smaller surface area in the right frontal pole. In contrast, an increase of 5-μg/m3 in PM2.5 exposure was associated with a 34.9 mm2 increase in right lateral orbital frontal surface area (Fig. 2B, Fig. 4). For cortical thickness, an increase of 5-μg/m3 in PM2.5 exposure was associated with thinner cortices (0.01–0.02 mm) in the left superior frontal, left orbital frontal, left cingulate cortex (rostral anterior, caudal anterior, posterior, isthmus), right inferior temporal, right parahippocampal, and right insula (Fig. 3B, Fig. 4). In addition, an increase of 5-μg/m3 in PM2.5 exposure was also found to be associated with increases in cortical thickness (0.01–0.04 mm) in the right lateral orbital frontal, right paracentral, right caudal anterior and posterior cingulate, and the left middle temporal cortex (Fig. 3B, Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

A) PM2.5-by-hemisphere interaction effect estimates; and B) Region-specific PM2.5 effect estimates on surface area (mm2) that differed statistically by hemisphere in the ABCD Study.

Footnote: A) Visualization of beta coefficients (95% CI) denoting regions associated with PM2.5 -by-hemisphere interaction presented with ‘*’ for passed False Discovery Rate correction. B) Visualization of beta coefficients (95% CI) denoting regions associated stratified post-hoc analyses within a given hemisphere derived from significant PM2.5 -by-hemisphere interactions presented with ‘*’ p < 0.05. PM2.5 units are 5 μg/m3.

Figure 3.

A) PM2.5-by-hemisphere interaction effect estimates; and B) Region-specific PM2.5 effect estimates on cortical thickness (mm) that differed statistically by hemisphere in the ABCD Study.

Footnote: A) Visualization of beta coefficients (95% CI) denoting regions associated with PM2.5 -by-hemisphere interaction presented with ‘*’ for passed False Discovery Rate correction. B) Visualization of beta coefficients (95% CI) denoting regions associated stratified post-hoc analyses within a given hemisphere derived from significant PM2.5 -by-hemisphere interactions presented with ‘*’ p < 0.05. PM2.5 units are 5 μg/m3.

Fig. 4.

Hemispheric-specific differences in regional effects of PM2.5 exposure on surface area and cortical thickness in the ABCD Study

Visualization of beta coefficients denoting regions significantly associated with PM2.5 (using a fixed increment of 5 μg/m3) within a given hemisphere based on stratified post-hoc analyses (P-values at p<0.05), including CUN: Cuneus; lOFC: Lateral Orbitofrontal; FP: Frontal Pole; SF: Superior Frontal; lOFC: Lateral Orbitofrontal; raCC: Rostral Anterior Cingulate; caCC: Caudal Anterior Cingulate; pCC: Posterior Cingulate; iCC: Isthmus Cingulate; PCC: Paracentral; ITC: Inferior Temporal; MTC: Middle Temporal; PHC: Parahippocampal. Negative associations are presented in dark-light blue and positive associations are presented in red-yellow.

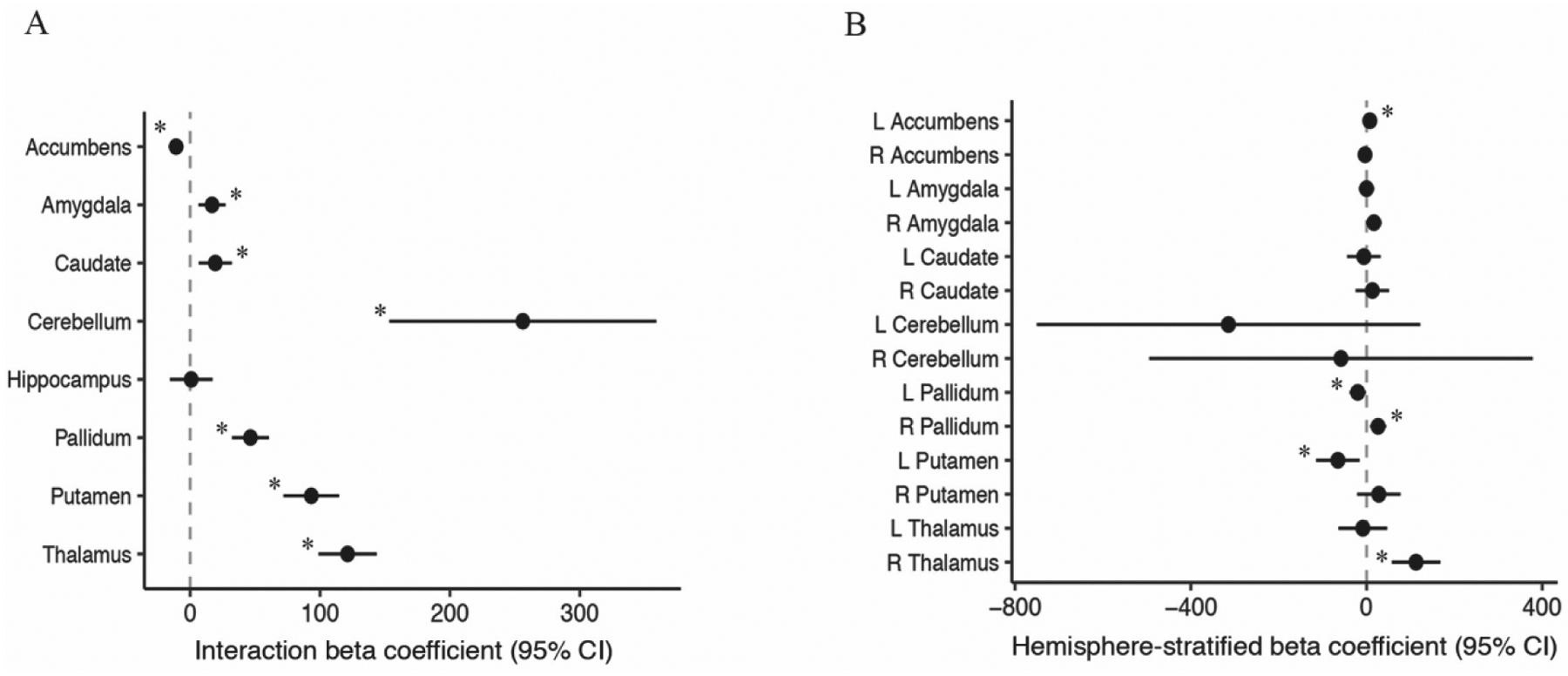

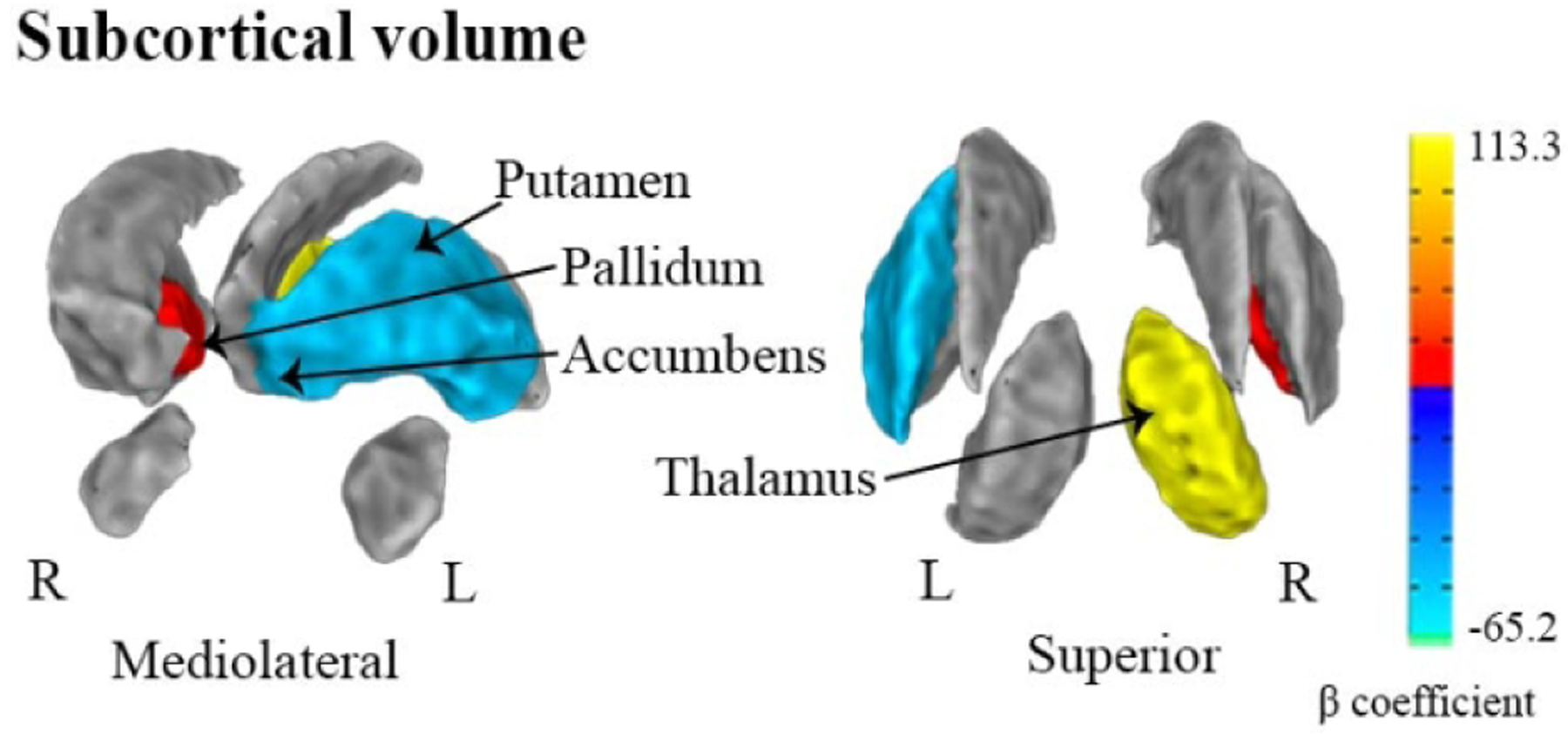

3.3. Links between residential PM2.5 exposure levels and brain volumes

Increased PM2.5 exposure was associated with hemispheric-specific differences in subcortical and cerebellum volumes, with the exception of the hippocampus (Fig. 5A). Regional effect estimates stratified by hemisphere revealed an increase of 5-μg/m3 in exposure was associated with a 112.7 mm3 increase in right thalamic volumes, 26.3 mm3 increase in the right pallidum, 7.4 mm3 in the left accumbens (Fig. 5B, Fig. 6). In constrast, an increase of 5-μg/m3 was also related to a 65.2 mm3 decrease in the left putamen and a 20.1 mm3 decrease in the left pallidum (Fig. 5B, Fig. 6). No significant associations were found between PM2.5 exposure and global measures of whole-brain surface area, cortical thickness, cortical volume or subcortical volumes (Table 2).

Figure 5.

A) PM2.5-by-hemisphere interaction effect estimates and; B) Region-specific PM2.5 effect estimates on cerebellum and subcortical volumes (mm3) that differed statistically by hemisphere in the ABCD Study.

Footnote: A) Visualization of beta coefficients (95% CI) denoting regions associated with PM2.5 -by-hemisphere interaction presented with ‘*’ for passed False Discovery Rate correction. B) Visualization of beta coefficients (95% CI) denoting regions associated stratified post-hoc analyses within a given hemisphere derived from significant PM2.5 -by-hemisphere interactions presented with ‘*’ p < 0.05. PM2.5 units are 5 μg/m3.

Fig. 6.

Hemispheric-specific differences in regional effects of PM2.5 exposure on subcortical volumes (mm3) in the ABCD Study

Visualization of beta coefficients denoting regions of subcortical volumes significantly associated with PM2.5 (using a fixed increment of 5 μg/m3) within a given hemisphere based on stratified post-hoc analyses (P-values at p<0.05). Negative associations are presented in dark-light blue and positive associations are presented in red-yellow.

Table 2.

Annual PM2.5 Average and Global Measures of Whole Brain Estimates in the ABCD Study

| ROI | Coefficients | CI (95%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cortical Surface area | 276.6 | −1080.0 | 1633.1 | 0.689 |

| Mean Cortical Thickness | −0.004 | −0.013 | 0.006 | 0.457 |

| Whole Brain Volume | 669.5 | −3056.5 | 4395.4 | 0.725 |

| Subcortical Gray Matter Volume | 71.4 | −184.0 | 326.8 | 0.583 |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid Volume | −2.6 | −20.2 | 15.0 | 0.771 |

| Intracranial Volume | 1676.5 | −8846.2 | 12199.1 | 0.755 |

| All Ventricles Volume | −192.3 | −679.5 | 294.9 | 0.439 |

| Lateral Ventricles Volume | −219.9 | −686.3 | 246.5 | 0.355 |

| Cerebral White Matter Volume | 1256.2 | −871.1 | 3383.5 | 0.247 |

ROI, Region of Interest; β, Beta coefficient; CI, Confidence Interval.

Note: The models are based on main effects of PM2.5. All models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, neighborhood quality, parental higher education, total family income, parental employment status, imaging device manufacturer, handedness and intracranial volume for volumetric measures, including random intercepts for ABCD site and familial relationship (participants belonging to the same family). Models were scaled for PM2.5 using a fixed increment of 5 μg/m3

3.4. PM2.5 exposure and neurocognitive performance

There were no significant associations between PM2.5 and task performance on individual measures of neurocognition or composites of total, crystallized or fluid cognition (Table 3).

Table 3.

Annual PM2.5 Average Exposure and Neurocognitive Performance in the ABCD Study

| NIH Toolbox Score | Coefficients | CI (95%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| List Sorting Working Memory Test | −0.2 | −1.2 | 0.9 | 0.76 |

| Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test | 0.7 | −0.1 | 1.6 | 0.09 |

| Dimensional Change Card Sort Test | 0.2 | −0.6 | 1.0 | 0.63 |

| Picture Vocabulary Test | −0.1 | −0.8 | 0.5 | 0.67 |

| Oral Reading Recognition Test | 0.3 | −0.3 | 1.0 | 0.282 |

| Picture Sequence Memory Test | −0.71 | −1.7 | 0.3 | 0.175 |

| Pattern Comparison Processing Speed Test | −1.1 | −2.4 | 0.3 | 0.117 |

| Total Cognition Composite | −0.1 | −0.8 | 0.7 | 0.85 |

| Crystallized Cognition Composite | 0.1 | −0.5 | 0.7 | 0.66 |

| Fluid Cognition Composite | −0.3 | −1.2 | 0.6 | 0.55 |

β, Beta coefficient; CI, Confidence Interval.

Note: The models are based on main effects of PM2.5. All models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, neighborhood quality, parental higher education, total family income, parental employment status, including random intercepts for ABCD site and familial relationship (participants belonging to the same family). Models were scaled for PM2.5 using a fixed increment of 5 μg/m3.

3.5. Sensitivity and exploratory analysis of sex differences in PM2.5 effects

Because some studies that have found sex differences in PM2.5 effects on behavior (Chiu et al., 2016; Sunyer et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017), we also performed analyses stratified by sex. However, we found no evidence that sex moderated the associations of PM2.5 with stratified hemispheric regions of surface area, cortical thickness, subcortical volume, whole brain measures and neurocognitive performance in children ages 9–10 years (STables 4–8). PM2.5 exposure levels were similar among subjects living <150m from a major roadway (Mean=7.53, SD=1.63 ug/m3), 150–300m (Mean=7.79, SD=1.57 ug/m3) or 300–600m (Mean=7.72, SD=1.59 ug/m3). A small, but significant, association was seen between PM2.5 exposure levels and population density (β=0.0001, 95% CI: 0.00008–0.000098, p<0.0001). Adjustment for population density and residential distance to major road did not materially change PM2.5 results (STables 9–11). We also explored heterogeneity of the PM2.5 exposure effect by site (by including a random slope of PM2.5 by site in our models) and did not find significant heterogeneity between PM2.5 exposure and any of the outcomes examined.

3. Discussion

This is the largest air pollution-brain MRI study (N=10,343) to examine effects of exposure to fine particulate matter on morphometric measures of developing brains of children (age 9–10 years) in the United States. In this respect, the sample size provided statistical power to examine the effects of PM2.5 by hemisphere in cortical-, subcortical brain regions, and neurocognitive outcomes. Annual residential PM2.5 exposure assigned to the primary address at baseline study enrollment was associated with hemispheric- and region-specific differences in gray matter. However, no associations were found with cognitive function as measured by the NIH Toolbox. The observed brain morphological findings were robust to adjustment for various socio-demographic factors and multiple comparison adjustment.

Our findings are congruent with previous studies suggesting brain regional specificity in neurotoxic effects of air pollution exposure during childhood (Pujol et al., 2016b; Pujol et al., 2016a). Children and adolescents may be especially at risk for neurotoxic effects of air pollution because their brain are still growing and they are developing vital learning skills as well as social and interpersonal competencies (Sebastian, Burnett, & Blakemore, 2008; Steinberg, 2005). Interestingly, PM2.5 exposure was associated with both increases and decreases in gray matter surface area, thickness, and volume. The observed regional- and hemispheric specific patterns of both positive and negative associations between PM2.5 and gray matter may reflect the dynamic neurodevelopmental trajectories across early life that vary by brain region. For instance, sensory motor and language functions reach peak volumes in early childhood while the prefrontal, temporal, and basal ganglia continue to mature up to mid-to-late twenties (Crone, 2009; Herting et al., 2018; Lebel & Deoni, 2018; Lebel, Treit, & Beaulieu, 2017; Sowell et al., 2003; Tamnes et al., 2017). A hallmark pattern of child and adolescent development is synaptogenesis and peak volume around age 10, followed by pruning of synapses and increases in myelination, which is captured on MRI as a decrease in cortical thickness (Gotts et al., 2013; Herting et al., 2018; Mallya & Deutch, 2018; Sowell et al., 2003). In line with these findings, we found regional specific associations between PM2.5 exposure and cortical thickness of the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and basal ganglia as well as differences in the directionality of associations by hemisphere. Interestingly, hemispheric differences have also been previously noted in typical patterns of cortical thickness, albeit the pattern of asymmetry was found to change between early childhood versus late adolescence (Shaw et al., 2011). Moreover, regional- and hemispheric- differences have also been noted in a number of neurodevelopmental and mental health disorders, including Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Shaw et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2009), autism (Eyler, Pierce, & Courchesne, 2012), and depression (W. Liu et al., 2016; Yucel et al., 2009). Additional research is needed to understand if environmental exposures, including PM2.5, may partially contribute to risk for these types of disorders through effects on hemispheric patterns of brain maturation across childhood and adolescence.

We hypothesize that annual PM2.5 exposure could alter the timing of the pruning process, either delaying or accelerating this process, in a regional and hemisphere specific manner. A possible biological mechanism of PM2.5 exposure on the pruning process could be through actions on microglia cells. Microglia engulf dendritic spines during synaptic pruning in adolescence (Mallya, Wang, Lee, & Deutch, 2018). Both animal studies and human studies in populations living in highly polluted cities indicate that PM exposure leads to changes within the brain (Block et al., 2004; Levesque et al., 2011; F. Liu et al., 2015; Ljubimova et al., 2018; Pope et al., 2016), including microglial activation (Calderon-Garciduenas et al., 2008; Ljubimova et al., 2018; Woodward et al., 2017). Additional experimental studies are needed to elucidate the underlying role of microglia and to identify additional plausible neurological consequences of PM2.5 exposure during adolescence, such as neuroinflammation, neurovascular damage, altered neurotransmitters, and up-regulation of genes encoding inflammatory cytokine pathways (Calderon-Garciduenas et al., 2008; Calderon-Garciduenas et al., 2015; Ljubimova et al., 2018; Pope et al., 2016).

The current study strengthens preliminary evidence from previous human studies suggesting that air pollution may exert region-specific neurotoxic effects on the brain (Guxens et al., 2018; Mortamais et al., 2017; Pujol et al., 2016b; Pujol et al., 2016a). A few studies have examined associations of prenatal or postnatal exposure to ambient air pollution and brain structure in children. One study found that higher prenatal PM2.5 exposure was associated with reduced cortical thickness in the right prefrontal cortex in 6 to 10 year-olds (Guxens et al., 2018). In another study of 7–9 year-old children, PAHs derived from PM2.5 exposure were associated with surface reductions largely seen in the left hemisphere, as well as more focal patterns of increases in surface area that were largely driven by white matter (Peterson et al., 2015). Our findings provide additional evidence that the brain is vulnerable to air pollution through postnatal development, as air pollution exposure at ages 9–10 was associated with concurrent brain structure morphology. Given that both the prenatal and childhood windows have been identified as robust periods of neuromaturation, future studies are needed to disentangle specific brain alterations due to prenatal versus postnatal ambient PM2.5 exposure.

Structural brain differences associated with ambient PM2.5 identified in the current study are of particular concern as exposure levels of ABCD sites (median= 5.1–10.4 μg/m3; overall range=1.72 – 15.9 μg/m3) were generally below the regulatory standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (12 μg/m3) (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2012) and the World Health Organization (10 μg/m3) (World Health Organization, 2005). Similarly low PM2.5 exposure levels in large, recent studies from the U.S. (N= 4 522 160; mean=10.1 μg/m3; range = 4.8–20.1 μg/m3) (Bowe, Xie, Yan, & Al-Aly, 2019) and Canada (N=299,500; mean (SD)=6.32 (2.54) μg/m3) (Pinault et al., 2016) were associated with increased mortality risk. Our study adds to emerging evidence that health effects of PM2.5 may be seen at concentrations below the national or international standards. While the majority of low to middle income countries do not meet standards of the U.S. EPA or WHO, 49% of high income countries in North America, Europe, and the Western Pacific have low PM2.5 exposure levels (World Health Organization, 2018). Thus, our findings of potential brain effects of PM2.5 in children may be most generalizable to countries and urban areas that are currently near meeting those worldwide standards. Consequently, our data suggest that current PM2.5 exposure across the U.S. may be an important environmental factor influencing patterns of structural brain development in childhood.

We did not observe associations of current childhood PM2.5 exposure with assessments of neurocognitive performance. In this respect, our results are not consistent with previous studies showing that residential exposure to fine particulate matter or its constituents is associated with deficits in general intelligence (Chiu et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2010; Perera et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2017) and poorer cognitive performance (Chiu et al., 2016). These differences between studies may be a function of exposure heterogeneity, type of exposure assessment, geographical location, sensitivity of cognitive tests implemented, or differences in study design. For instance, a number of studies focused on PAHs, a specific component of PM2.5 (Edwards et al., 2010; Perera et al., 2009). The two studies assessing childhood PM2.5 exposure and cognitive outcomes conducted in the U.S. (Perera et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2017) had small sample size, geographical/spatial coverage limited to cities (New York, Southern California), restricted sociocultural backgrounds (ethnic minorities) and/or higher exposed populations that could possibly explain observed associations attributable to unmeasured or residual confounding. Notwithstanding absence of measureable neuroperformance deficits, the observed alterations in brain structure found in the present study may still have important clinical relevance and public health implications. Specifically, these structural alterations could be early biomarkers of neurocognitive impairments, or other unfavorable neurological outcomes, that may develop over time. Specifically, recent neuroscience has identified the need to understand how individual differences in brain maturation contribute to vulnerability (Foulkes & Blakemore, 2018); trajectories of brain development at either extreme (reduced and/or augmented structural brain development via over or under pruning) may be linked to various cognitive and mental health problems (Gogtay & Thompson, 2010). From childhood to adulthood, individuals typically show a ~1mm change in gray matter (Tamnes et al., 2017) with about ~0.021 mm/year seen during childhood (Zhou, Lebel, Treit, Evans, & Beaulieu, 2015). In the current study an increase of 5-μg/m3 was associated with differences in cortical thickness on the magnitude ranging from 0.01–0.04 mm, suggesting that continual exposure to PM2.5 during childhood and adolescence could substantially impact an individual’s brain growth trajectories with potentially lifelong consequences.

The study has several strengths, including a large, diverse sample with air pollution estimates at the individual level with high spatiotemporal precision (1-km2 resolution) (Di et al., 2019), and the ability to adjust for important demographic and socio-economic confounders. This unique sample provided us with complete structural evaluation of MRI measurements of cortical thickness, surface area, subcortical volume in a regional fashion as well as whole-brain assessments and explored a critical time window of children’s brain maturation when dynamic changes accompany cortical development. However, a few limitations should be noted. The cross-sectional design is a limitation to causal inference, especially since brain maturation is an ongoing developmental process. Future research is needed to determine the impact of PM2.5 exposure on the subsequent maturation of brain regions during the transition period from early childhood to adolescence, as these prospectively collected data become available through ABCD or other cohorts. As the ABCD dataset does not currently include PM2.5 estimates for prenatal and earlier life residential addresses, we were not able to assess the role of prenatal PM2.5 exposure in brain structure and function. Once lifetime address history has been collected (which is planned for follow-up visits in the ABCD cohort), it will be a priority to assess early life PM associations with brain health. The ABCD study enrollment process was dynamically monitored to ensure the study met target sex, socioeconomic, ethnic, and racial diversity (Garavan et al., 2018). However, participation was limited to the 21 study sites, which may contribute to ecological confounding effects. The current study was also limited in exposure assessment as it did not include personal, home, or school-based measures of air pollution using real-time monitors. In addition, the ABCD dataset does not currently contain estimates of other regional pollutants at the 1-km2 resolution or PM2.5 constituents (for example polyaromatic hydrocarbons, elemental carbon, or metals), or the near-roadway PM mixture that may be more toxic than mass alone, and may vary across the participating study sites. However, in sensitivity analyses PM2.5 effect estimates did not vary substantially across study site locations. Previous studies have suggested PM2.5 findings may be driven by traffic-related pollution (Pujol et al., 2016a; Sunyer et al., 2015; Sunyer et al., 2017). However, our results remained robust to adjustment for distance to major roadway, as well as for population density. Distance to major roadway is only a proxy for near-roadway exposure. Better indicators of near-roadway air pollution exposure and of exposure to PM2.5 constituents are needed to assess their effects.

Conclusions

The current study found associations between childhood brain structure and PM exposure, even at levels of exposure be low the current standard. While progress has been made in improving air quality, our findings indicate that additional research is needed to understand the long-term consequences of neurodevelopmental effects of air pollution at levels children are currently experiencing across the U.S.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Largest study to date on fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and brain in children

Individual residential PM2.5 exposure assigned for 10,343 U.S. children at 21 sites

PM2.5 associated with regional- and hemisphere-specific brain differences

PM2.5 was not associated with NIH Toolbox performance

Findings were similar in both boys and girls

Acknowledgements

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children age 9-10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD Study is supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants [U01DA041022, U01DA041028, U01DA041048, U01DA041089, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041120, U01DA041134, U01DA041148, U01DA041156, U01DA041174, U24DA041123, U24DA041147]. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/nih-collaborators. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/principal-investigators.html. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators. The ABCD data repository grows and changes over time. The ABCD data used in this report came from 10.15154/1504041. Additional support for this project, including the estimates and assignment of PM2.5 exposure to each subject’s residential address, was provided by the National Institutes of Health [NIEHS P30ES007048-23S1, 3P30ES000002-55S1, NIH P01ES022845] and EPA grants [RD 83587201, RD-83544101]. The Rose Hills Foundation also supported the efforts of MH and DCS.

Abbreviations:

- PM2.5

particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter of ≤2.5 μm

- ABCD

Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Afifi AK, & Bergman RA (2005). Functional neuroanatomy : text and atlas. New York; London: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Auchter AM, Hernandez Mejia M, Heyser CJ, Shilling PD, Jernigan TL, Brown SA, … Dowling GJ (2018). A description of the ABCD organizational structure and communication framework. Dev Cogn Neurosci. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagot KS, Matthews SA, Mason M, Squeglia LM, Fowler J, Gray K, … Patrick K (2018). Current, future and potential use of mobile and wearable technologies and social media data in the ABCD study to increase understanding of contributors to child health. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Albaugh MD, Avenevoli S, Chang L, Clark DB, Glantz MD, … Sher KJ (2018). Demographic, physical and mental health assessments in the adolescent brain and cognitive development study: Rationale and description. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith T, Cecil K, Altaye M, Severs R, Wolfe C, Percy Z, … Ryan P (2020). Reduced gray matter volume and cortical thickness associated with traffic-related air pollution in a longitudinally studied pediatric cohort. PLoS One, 15(1), e0228092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beelen R, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Stafoggia M, Andersen ZJ, Weinmayr G, Hoffmann B, … Hoek G (2014). Effects of long-term exposure to air pollution on natural-cause mortality: an analysis of 22 European cohorts within the multicentre ESCAPE project. Lancet, 383(9919), 785–795. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62158-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Elder A, Auten RL, Bilbo SD, Chen H, Chen JC, … Wright RJ (2012). The outdoor air pollution and brain health workshop. Neurotoxicology, 33(5), 972–984. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Wu X, Pei Z, Li G, Wang T, Qin L, … Veronesi B (2004). Nanometer size diesel exhaust particles are selectively toxic to dopaminergic neurons: the role of microglia, phagocytosis, and NADPH oxidase. FASEB J, 18(13), 1618–1620. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1945fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowe B, Xie Y, Yan Y, & Al-Aly Z (2019). Burden of Cause-Specific Mortality Associated With PM2.5 Air Pollution in the United States. JAMA Netw Open, 2(11), e1915834. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeyer S, & D’Angiulli A (2016). How air pollution alters brain development: the role of neuroinflammation. Transl Neurosci, 7(1), 24–30. doi: 10.1515/tnsci-2016-0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Garciduenas L, Mora-Tiscareno A, Ontiveros E, Gomez-Garza G, Barragan-Mejia G, Broadway J, … Engle RW (2008). Air pollution, cognitive deficits and brain abnormalities: a pilot study with children and dogs. Brain Cogn, 68(2), 117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Garciduenas L, Vojdani A, Blaurock-Busch E, Busch Y, Friedle A, Franco-Lira M, … D’Angiulli A (2015). Air pollution and children: neural and tight junction antibodies and combustion metals, the role of barrier breakdown and brain immunity in neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis, 43(3), 1039–1058. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Cannonier T, Conley MI, Cohen AO, Barch DM, Heitzeg MM, … Workgroup AIA (2018). The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study: Imaging acquisition across 21 sites. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Tottenham N, Liston C, & Durston S (2005). Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? Trends Cogn Sci, 9(3), 104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for International Earth Science Information Network - CIESIN - Columbia University. (2016). Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population Density Adjusted to Match 2015 Revision UN WPP Country Totals. Retrieved from: 10.7927/H4HX19NJ [DOI]

- Chiu YH, Hsu HH, Coull BA, Bellinger DC, Kloog I, Schwartz J, … Wright RJ (2016). Prenatal particulate air pollution and neurodevelopment in urban children: Examining sensitive windows and sex-specific associations. Environ Int, 87, 56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford A, Lang L, Chen R, Anstey KJ, & Seaton A (2016). Exposure to air pollution and cognitive functioning across the life course--A systematic literature review. Environ Res, 147, 383–398. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AJ, Brauer M, Burnett R, Anderson HR, Frostad J, Estep K, … Forouzanfar MH (2017). Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet, 389(10082), 1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30505-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Dowling GJ, & Garavan H (2019). Ensuring the Best Use of Data: The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study. JAMA Pediatr. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa LG, Cole TB, Coburn J, Chang YC, Dao K, & Roque PJ (2017). Neurotoxicity of traffic-related air pollution. Neurotoxicology, 59, 133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA (2009). Executive functions in adolescence: inferences from brain and behavior. Dev Sci, 12(6), 825–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00918.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Fischl B, & Sereno MI (1999). Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage, 9(2), 179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Prado Bert P, Mercader EMH, Pujol J, Sunyer J, & Mortamais M (2018). The Effects of Air Pollution on the Brain: a Review of Studies Interfacing Environmental Epidemiology and Neuroimaging. Curr Environ Health Rep, 5(3), 351–364. doi: 10.1007/s40572-018-0209-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Q, Amini H, Shi L, Kloog I, Silvern R, Kelly J, … Schwartz J (2019). An ensemble-based model of PM2.5 concentration across the contiguous United States with high spatiotemporal resolution. Environ Int, 130, 104909. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.104909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SC, Jedrychowski W, Butscher M, Camann D, Kieltyka A, Mroz E, … Perera F (2010). Prenatal exposure to airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and children’s intelligence at 5 years of age in a prospective cohort study in Poland. Environ Health Perspect, 118(9), 1326–1331. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyler LT, Pierce K, & Courchesne E (2012). A failure of left temporal cortex to specialize for language is an early emerging and fundamental property of autism. Brain, 135(Pt 3), 949–960. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein Ewing SW, Chang L, Cottler LB, Tapert SF, Dowling GJ, & Brown SA (2018). Approaching Retention within the ABCD Study. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes L, & Blakemore SJ (2018). Studying individual differences in human adolescent brain development. Nat Neurosci, 21(3), 315–323. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0078-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H, Bartsch H, Conway K, Decastro A, Goldstein RZ, Heeringa S, … Zahs D (2018). Recruiting the ABCD sample: Design considerations and procedures. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaniga MS (1995). Principles of human brain organization derived from split-brain studies. Neuron, 14(2), 217–228. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90280-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon RC, Wagster MV, Hendrie HC, Fox NA, Cook KF, & Nowinski CJ (2013). NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function. Neurology, 80(11 Suppl 3), S2–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e5f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, … Rapoport JL (1999). Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nature Neuroscience, 2(10), 861–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis AC, … Thompson PM (2004). Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 101(21), 8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, & Thompson PM (2010). Mapping gray matter development: implications for typical development and vulnerability to psychopathology. Brain Cogn, 72(1), 6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Google Maps Platform Documentation. (2019). Geocoding API. Retrieved from http://developers.google.com/maps/documentation

- Gotts SJ, Jo HJ, Wallace GL, Saad ZS, Cox RW, & Martin A (2013). Two distinct forms of functional lateralization in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(36), E3435–3444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302581110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, & Brumback B (2002). An overview of relations among causal modelling methods. Int J Epidemiol, 31(5), 1030–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guxens M, Garcia-Esteban R, Giorgis-Allemand L, Forns J, Badaloni C, Ballester F, … Sunyer J (2014). Air pollution during pregnancy and childhood cognitive and psychomotor development: six European birth cohorts. Epidemiology, 25(5), 636–647. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guxens M, Lubczynska MJ, Muetzel RL, Dalmau-Bueno A, Jaddoe VWV, Hoek G, … El Marroun H (2018). Air Pollution Exposure During Fetal Life, Brain Morphology, and Cognitive Function in School-Age Children. Biol Psychiatry, 84(4), 295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler DJ, Hatton SN, Makowski C, Cornejo MD, Fair DA, Dick AS, … Dale AM (2018). Image processing and analysis methods for the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Akshoomoff N, Tulsky D, Mungas D, Weintraub S, Dikmen S, … Gershon R (2014). Reliability and validity of composite scores from the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery in adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 20(6), 588–598. doi: 10.1017/S1355617714000241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herting MM, Johnson C, Mills KL, Vijayakumar N, Dennison M, Liu C, … Tamnes CK (2018). Development of subcortical volumes across adolescence in males and females: A multisample study of longitudinal changes. Neuroimage, 172, 194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan TL, Brown SA, & Dowling GJ (2018). The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study. J Res Adolesc, 28(1), 154–156. doi: 10.1111/jora.12374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N (2010). Functional specificity in the human brain: a window into the functional architecture of the mind. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 107(25), 11163–11170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005062107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karner AA, Eisinger DS, & Niemeier DA (2010). Near-roadway air quality: synthesizing the findings from real-world data. Environ Sci Technol, 44(14), 5334–5344. doi: 10.1021/es100008x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern JK, Geier DA, Homme KG, King PG, Bjorklund G, Chirumbolo S, & Geier MR (2017). Developmental neurotoxicants and the vulnerable male brain: a systematic review of suspected neurotoxicants that disproportionally affect males. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis, 77(4), 269–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong XZ, Mathias SR, Guadalupe T, Group ELW, Glahn DC, Franke B, … Francks C (2018). Mapping cortical brain asymmetry in 17,141 healthy individuals worldwide via the ENIGMA Consortium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 115(22), E5154–E5163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718418115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, & Deoni S (2018). The development of brain white matter microstructure. Neuroimage. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Treit S, & Beaulieu C (2017). A review of diffusion MRI of typical white matter development from early childhood to young adulthood. NMR Biomed. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque S, Taetzsch T, Lull ME, Kodavanti U, Stadler K, Wagner A, … Block ML (2011). Diesel exhaust activates and primes microglia: air pollution, neuroinflammation, and regulation of dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Environ Health Perspect, 119(8), 1149–1155. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Huang Y, Zhang F, Chen Q, Wu B, Rui W, … Ding W (2015). Macrophages treated with particulate matter PM2.5 induce selective neurotoxicity through glutaminase-mediated glutamate generation. J Neurochem, 134(2), 315–326. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Mao Y, Wei D, Yang J, Du X, Xie P, & Qiu J (2016). Structural Asymmetry of Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Correlates with Depressive Symptoms: Evidence from Healthy Individuals and Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Neurosci Bull, 32(3), 217–226. doi: 10.1007/s12264-016-0025-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljubimova JY, Braubach O, Patil R, Chiechi A, Tang J, Galstyan A, … Holler E (2018). Coarse particulate matter (PM2.5–10) in Los Angeles Basin air induces expression of inflammation and cancer biomarkers in rat brains. Sci Rep, 8(1), 5708. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23885-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciana M, Bjork JM, Nagel BJ, Barch DM, Gonzalez R, Nixon SJ, & Banich MT (2018). Adolescent neurocognitive development and impacts of substance use: Overview of the adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) baseline neurocognition battery. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallya AP, & Deutch AY (2018). (Micro)Glia as Effectors of Cortical Volume Loss in Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull, 44(5), 948–957. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallya AP, Wang HD, Lee HNR, & Deutch AY (2018). Microglial Pruning of Synapses in the Prefrontal Cortex During Adolescence. Cereb Cortex. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM (1990). Large-scale neurocognitive networks and distributed processing for attention, language, and memory. Ann Neurol, 28(5), 597–613. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortamais M, Pujol J, van Drooge BL, Macia D, Martinez-Vilavella G, Reynes C, … Sunyer J (2017). Effect of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on basal ganglia and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in primary school children. Environ Int, 105, 12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujahid MS, Diez Roux AV, Morenoff JD, & Raghunathan T (2007). Assessing the measurement properties of neighborhood scales: from psychometrics to ecometrics. Am J Epidemiol, 165(8), 858–867. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel BJ, Herting MM, Maxwell EC, Bruno R, & Fair D (2013). Hemispheric lateralization of verbal and spatial working memory during adolescence. Brain Cogn, 82(1), 58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2013.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera FP, Li Z, Whyatt R, Hoepner L, Wang S, Camann D, & Rauh V (2009). Prenatal airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure and child IQ at age 5 years. Pediatrics, 124(2), e195–202. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Rauh VA, Bansal R, Hao X, Toth Z, Nati G, … Perera F (2015). Effects of prenatal exposure to air pollutants (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) on the development of brain white matter, cognition, and behavior in later childhood. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(6), 531–540. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinault L, Tjepkema M, Crouse DL, Weichenthal S, van Donkelaar A, Martin RV, … Burnett RT (2016). Risk estimates of mortality attributed to low concentrations of ambient fine particulate matter in the Canadian community health survey cohort. Environ Health, 15, 18. doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0111-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA 3rd, Bhatnagar A, McCracken JP, Abplanalp W, Conklin DJ, & O’Toole T (2016). Exposure to Fine Particulate Air Pollution Is Associated With Endothelial Injury and Systemic Inflammation. Circ Res, 119(11), 1204–1214. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta D, Narduzzi S, Badaloni C, Bucci S, Cesaroni G, Colelli V, … Forastiere F (2016). Air Pollution and Cognitive Development at Age 7 in a Prospective Italian Birth Cohort. Epidemiology, 27(2), 228–236. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol J, Fenoll R, Macia D, Martinez-Vilavella G, Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Rivas I, … Sunyer J (2016b). Airborne copper exposure in school environments associated with poorer motor performance and altered basal ganglia. Brain Behav, 6(6), e00467. doi: 10.1002/brb3.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol J, Martinez-Vilavella G, Macia D, Fenoll R, Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Rivas I, … Sunyer J (2016a). Traffic pollution exposure is associated with altered brain connectivity in school children. Neuroimage, 129, 175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Hall WC, LaMantia AS, Mooney RD, … White LE (2001). Language and Lateralization In Neuroscience. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P (2009). Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nat Rev Neurosci, 10(10), 724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrn2719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raznahan A, Shaw P, Lalonde F, Stockman M, Wallace GL, Greenstein D, … Giedd JN (2011). How does your cortex grow? J Neurosci, 31(19), 7174–7177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0054-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CDT,S; Schumacker RE (2013). Tests of Moderation Effects: Difference in Simple Slopes versus the Interaction Term. Multiple Linear Regression Viewpoints, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian C, Burnett S, & Blakemore SJ (2008). Development of the self-concept during adolescence. Trends Cogn Sci, 12(11), 441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Gilliam M, Liverpool M, Weddle C, Malek M, Sharp W, … Giedd J (2011). Cortical development in typically developing children with symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity: support for a dimensional view of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry, 168(2), 143–151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, Clasen L, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, … Giedd J (2006). Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature, 440(7084), 676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature04513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Lalonde F, Lepage C, Rabin C, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, … Rapoport J (2009). Development of cortical asymmetry in typically developing children and its disruption in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 66(8), 888–896. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Delis D, Stiles J, & Jernigan TL (2001). Improved memory functioning and frontal lobe maturation between childhood and adolescence: a structural MRI study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 7(3), 312–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Peterson BS, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, & Toga AW (2003). Mapping cortical change across the human life span. Nat Neurosci, 6(3), 309–315. doi: 10.1038/nn1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Leonard CM, Welcome SE, Kan E, & Toga AW (2004). Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and brain growth in normal children. J Neurosci, 24(38), 8223–8231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1798-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sram RJ, Veleminsky M Jr., Veleminsky M Sr., & Stejskalova J (2017). The impact of air pollution to central nervous system in children and adults. Neuro Endocrinol Lett, 38(6), 389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn Sci, 9(2), 69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunyer J, Esnaola M, Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Forns J, Rivas I, Lopez-Vicente M, … Querol X (2015). Association between traffic-related air pollution in schools and cognitive development in primary school children: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med, 12(3), e1001792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunyer J, Suades-Gonzalez E, Garcia-Esteban R, Rivas I, Pujol J, Alvarez-Pedrerol M, … Basagana X (2017). Traffic-related Air Pollution and Attention in Primary School Children: Short-term Association. Epidemiology, 28(2), 181–189. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamnes CK, Herting MM, Goddings AL, Meuwese R, Blakemore SJ, Dahl RE, … Mills KL (2017). Development of the Cerebral Cortex across Adolescence: A Multisample Study of Inter-Related Longitudinal Changes in Cortical Volume, Surface Area, and Thickness. J Neurosci, 37(12), 3402–3412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3302-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson EM (2019). Air Pollution, Stress, and Allostatic Load: Linking Systemic and Central Nervous System Impacts. J Alzheimers Dis, 69(3), 597–614. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of the Interior. (2017). One Million-Scale Major Roads of the United States. Retrieved from http://nationalmap.gov/small_scale/mld/1roadsl.html

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2012). Revised Air Quality Standards for Particle Pollution and Updates to the Air Quality Index (AQI). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-04/documents/2012_aqi_factsheet.pdf

- Uban KA, Horton MK, Jacobus J, Heyser C, Thompson WK, Tapert SF, … Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development, S. (2018). Biospecimens and the ABCD study: Rationale, methods of collection, measurement and early data. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendetti MS, Johnson EL, Lemos CJ, & Bunge SA (2015). Hemispheric differences in relational reasoning: novel insights based on an old technique. Front Hum Neurosci, 9, 55. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, Croyle RT, Bianchi DW, Gordon JA, Koroshetz WJ, … Weiss SRB (2018). The conception of the ABCD study: From substance use to a broad NIH collaboration. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Tuvblad C, Younan D, Franklin M, Lurmann F, Wu J, … Chen JC (2017). Socioeconomic disparities and sexual dimorphism in neurotoxic effects of ambient fine particles on youth IQ: A longitudinal analysis. PLoS One, 12(12), e0188731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelazo PD, Slotkin J, … Gershon R (2014). The cognition battery of the NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function: validation in an adult sample. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 20(6), 567–578. doi: 10.1017/S1355617714000320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HY, Hsueh YH, Messam LL, & Hertz-Picciotto I (2009). Methods of covariate selection: directed acyclic graphs and the change-in-estimate procedure. Am J Epidemiol, 169(10), 1182–1190. doi:kwp035 [pii] 10.1093/aje/kwp035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward NC, Levine MC, Haghani A, Shirmohammadi F, Saffari A, Sioutas C, … Finch CE (2017). Toll-like receptor 4 in glial inflammatory responses to air pollution in vitro and in vivo. J Neuroinflammation, 14(1), 84. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0858-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2005). WHO Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide: Summary of risk assessment. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69477/WHO_SDE_PHE_OEH_06.02_eng.pdf;jsessionid=31EE3DC816945B0DD9E7027348EB5E08?sequence=1 [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2013). Health effects of particulate matter: Policy implications for countries in eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/189051/Health-effects-of-particulate-matter-final-Eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2018). Exposure to ambient air pollution from particulate matter for 2016. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/airpollution/data/AAP_exposure_Apr2018_final.pdf?ua=1

- Yucel K, McKinnon M, Chahal R, Taylor V, Macdonald K, Joffe R, & Macqueen G (2009). Increased subgenual prefrontal cortex size in remitted patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res, 173(1), 71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Lebel C, Treit S, Evans A, & Beaulieu C (2015). Accelerated longitudinal cortical thinning in adolescence. Neuroimage, 104, 138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.