Abstract

Contexts are known to affect hedonic and emotional responses to various food products. This study was conducted to investigate the effects of context on consumer acceptance and emotion of a domestic food and an unfamiliar ethnic food. Here, 97 Chinese and 83 Koreans rated hedonic and emotional responses to Korean shallot-seafood pancake (Haemul-pajeon) and Chinese shallot pancake (Cōngyóubĭng), in a sensory or ethnic context. Context did not significantly influence liking, but the Koreans’ liking for Cōngyóubĭng significantly decreased in ethnic context compared to sensory context. Context significantly influenced eliciting positive emotions to domestic foods, whereas the context that increased positive emotions differed by the nationality of the panel. Ethnic food evaluated in ethnic context elicited emotions with negative valence or high arousal, whereas actual tasting significantly reduced these emotions. The results suggest that previous experiences and associations moderate the effect of context on emotions and acceptance.

Keywords: Context, Emotion, Cross-cultural study, Ethnic food, Liking

Introduction

Ethnic food refers to “foods from an ethnic group’s or a country’s cuisine, which is culturally and socially accepted by consumers outside of the respective ethnic groups” (Kwon, 2015). Increases in encounters with other cultures through tourism, trade, immigration, and mass media, including online social networks, have stimulated a demand for indigenous ethnic food products (Mak et al., 2012). The global ethnic food market was valued at approximately $365 billion in 2018, and its average annual growth rate was estimated at 11.80% over the forecast period of 2019–2024 (Mordor Intelligence, 2019). China has particularly become an emerging market for Korean ethnic food, owing to the growing popularity of Korean pop culture and Chinese consumers’ perception that Korean food is safe and reliable (Jang and Paik, 2012; Yan, 2012). Korean food exports to China reached $3.62 trillion in 2016, which is 18% greater than the previous year (Park, 2016). Accordingly, efforts to launch products based on Korean traditional recipes targeting the Chinese market are actively being undertaken to expand food export.

Recently there has been a growing research interest in food-evoked emotional reactions, since emotions are closely related with food acceptance (Piqueras-Fiszman and Jaeger, 2014a; 2014b). Disliking of unfamiliar foods is strongly correlated with negative emotions, such as fear and doubtfulness (Shim et al., 2019); whereas positive emotions, such as joy, happiness, and satisfaction, have a significant positive correlation with food liking (Cardello et al., 2012). Furthermore, Dalenberg et al., (2014) reported that emotional responses better predict individual food choices than liking. The relationship between emotion and liking may have a practical implication in developing a strategy to improve liking for ethnic foods, because ethnic foods are generally perceived as unfamiliar by foreign consumers and this perception causes neophobic responses that result in negative hedonic and emotional responses (Hong et al., 2014; Rozin and Vollmecke, 1986). From the correlation between positive emotions and liking, it is assumed that elicitation of positive emotion from unfamiliar ethnic food may have a positive impact on liking.

It is generally agreed that emotions are distinguished from other affective feelings, such as attitudes, personality traits, or moods (Meiselman, 2015). Compared with other affective feelings, emotions are characterized by rapid change, high intensity, and short lasting (Spinelli and Monteleone, 2018). Emotions can be interpreted and classified by mapping them in an affective space constructed from two basic dimensions of emotion, namely valence (positive-negative affect) and arousal (calm-exciting) (Thomson and Crocker, 2013).

Considerable attention has been given to the effects of context on emotional responses. Context refers to a series of events or experiences that are not part of a reference event but are related to the reference event, and in the field of food, environmental-cultural, personal, and sociocultural factors have been suggested as contextual factors that can influence food intake and choices (Rozin and Tuorila, 1993). Dorado et al. (2016) reported that consumers rated positive emotions evoked from beer higher and negative emotions lower when they were asked to freely elicit a beer-drinking scenario compared to a no-scenario condition. Also, beer samples were better discriminated in terms of liking and emotional responses in the scenario condition than in the no-scenario condition. Situational information and emotions may be encoded with foods while it is consumed. Thus emotions could be retrieved when faced with the situation that is similar to the experienced one. Even when encountered with a novel situation, retrieval can occur with the aid of analogy (Piqueras-Fiszman and Spence, 2015). Furthermore, evoked context can influence affective responses through assimilation or contrast effect of which theoretical background is based on Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory (1957). This theory proposes that negative responses to a stimulus result from a negative psychological status called dissonance when belief, values, perceptions, behaviors, and attitude are not consistent with one another. In sensory science, if the sensory experience of a product confirmed the expectation generated by an evoked context, the affective responses will shift toward a more positive direction (assimilation); however, when sensory expectation is not confirmed by the actual performance, much negative responses will be produced (contrast) (Cardello and Meiselman, 2018). Thus it is assumed that evoked context is also likely to influence positive or negative emotion elicitation through assimilation or contrast, which are closely related with liking.

This study was conducted to investigate the effect of context on emotional and hedonic responses to unfamiliar ethnic foods. More specifically, this study focused on Chinese consumers’ responses to Korean food developed for the Chinese market under a linguistically evoked context using a short product description. Based on the assimilation and contrast models, it is hypothesized that more positive emotional and hedonic responses will be elicited when an appropriate context that is consistent with the consumers’ perception of the product compared with when an evoked context is inconsistent. Therefore, the outcomes of this study may expectedly provide alternative strategies to improve foreign consumers’ acceptance of unfamiliar Korean ethnic foods.

Materials and methods

Sample

Based on the result from preliminary focus group interviews (FGI), Haemul-pajeon (Korean scallion and seafood pancake) was selected as a sample that signifies unfamiliar ethnic food and Cōngyóubĭng (Chinese scallion pancake) was chosen as familiar domestic food and Chinese counterpart of Haemul-pajeon since it was considered to be most similar with Haemul-pajeon. Haemul-pajeon was manufactured as a frozen ready-to-heat (RTH) product by Ourhome R&D center (Seongnam-si, Kyeonggi-do, Korea). The frozen RTH type of Cōngyóubĭng product (Rande Food Co., Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan) was purchased from a local grocery. The products were stored at – 20 °C until the test, and used within a month after reception.

The samples were prepared following the manufacturer’s guideline. Two sheets of Haemul-pajeon (diameter, 13 cm; thickness, 1.5 cm) was cooked in a 28 cm-diameter frying pan (Tefal D2300612, Group SEB, Ecully, France), which had been preheated on a portable gas stove (ST-001A, SUNTOUCH Co., Ltd. Korea) at the strong heat setting for 30 s, with 9 mL cooking oil (Soybean oil, Sajo, Incheon, Korea) for 2 min on medium heat for each side, turning it over every 1 min. One sheet of Cōngyóubĭng (diameter, 20 cm; thickness, 1 cm) was cooked in frying pan with 15 mL cooking oil in the same way as for Haemul-pajeon. One sheet of Haemul-pajeon was cut into six pieces, and one sheet of Cōngyóubĭng was cut into eight pieces, and two pieces of each product were served per person on a disposable white polypropylene plate (diameter 14 cm, height 1.5 cm) coded with three-digit random numbers. The samples were presented immediately after cooking, as requested by the panelists. The temperature of the samples at the time of tasting was 60 ± 1 °C.

Consumer test

Panel

From the series of preliminary FGIs, it was speculated that the target consumers of Korean foods in China would be young people in their 20 s and early 30 s who are interested in Korean pop culture. Therefore, the recruitment targeted Chinese consumers in their 20 s. The Chinese panel was recruited by posting a flyer in the Korean language institutes at universities and Chinese student communities in Seoul, Korea. Among all potential participants, 97 Chinese consumers residing in Korea were recruited. Although Chinese consumers’ responses were main research interest, Koreans were also recruited as a “control” group to cross-culturally compare their responses. Through offline and online advertisements, 83 Koreans in the same age range as the Chinese participants were recruited. A signed consent form was obtained from all participants. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Kookmin University Institutional Review Board (KMU-201611-HR-129).

Procedure

The samples were evaluated both in the context that emphasized sensory characteristics (sensory context: “This product contains plenty of mussels, clams, and shrimp”/“This product has a light and savory flavor with fragrant green onion”) and ethnic characteristics (ethnic context: “You can enjoy the authentic taste of Korea/China”). Context was verbally evoked by providing the panel with the aforementioned statements. The context-forming phrases were first developed from the product description, and then verified in an interview setting as to whether the phrase can evoke the context as intended, whether the length and tone of the phrase was adequate and neutral, and whether they had the similar weight across the products and context. The context-forming phrases and ballots were translated in Chinese by a bilingual translator, and then back-translated by another translator for verification.

The participants were introduced briefly to the test procedure and rinsing protocol before the test began. They rated expected liking after reading the given context using a 9-point category scale (1—dislike very much; 9—like very much). After then, the participants selected all emotional terms evoked by the sample under each context and evaluated their intensities using a 5-point category scale (1—weak; 5—strong) following the rate-all-that-apply (RATA) test protocol. The 22 emotional terms previously developed by Kim and Hong (2020) were used in the ballot. The presentation of emotional terms on the ballot were randomized across panelists, samples, and contexts.

After a 3-min break, the participants tasted a sample and evaluated liking and emotional terms in the presence of context. Participants were asked to rinse their mouth with filtered water (22 °C ± 2 °C) between samples. Finally, the participants’ demographic and eating habit information were collected.

A within-subject design was applied to allow participants to evaluate both samples in both contexts. The presentation order of samples and context was balanced across participants. The instructions and ballots were presented in either Korean or Chinese, depending on the nationality of the participant.

Statistical analysis

The effects of the factors on liking was investigated using the analysis of variance (ANOVA). The ANOVA model included nationality of panel, types of samples, tasting, and context as main factors, as well as their secondary and tertiary interactions.

Prior to emotional response analysis, one sample t-test was applied to examine whether near-zero RATA ratings were significantly different from zero. A multivariate ANOVA was performed to investigate the effects of factors on the RATA results from a holistic view. A univariate ANOVA was conducted to investigate the effects of the factors on individual emotional terms once the holistic difference was found. However, comparisons between both countries were not taken into account for the ANOVA of RATA tests, because the meanings of Chinese and Korean terms may not exactly match due to cultural and linguistic differences (Spinelli and Montelleone, 2018). Also, the valence and arousal potentials of the corresponding terms showed cross-cultural differences between China and Korea (Kim and Hong, 2020). Thus, Korean and Chinese emotion data were analyzed separately, and their ANOVA models included panel, samples, tasting, context, and their secondary and tertiary interactions. Panel was considered as random effect while other factors were treated as fixed effect. Duncan’s multiple range test was conducted as post-hoc analysis. The valence and arousal potentials measured for each term in the previous study (Kim and Hong, 2020) were used for the interpretation of the results.

A Chi square test was performed to test the significance of cross-cultural differences in the demographic data and eating habits. The SPSS software (ver. 23, IBM, New York, United State) was used for statistical analysis. The level of significance was set to p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results and discussion

Consumer demographics

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants. There were significant differences in some variables between Korean and Chinese panels, such as gender ratio, duration of stay in the other country, and experience in Haemul-pajeon by Chinese and Cōngyóubĭng by Koreans, since the Chinese panel was recruited among those who resided in Korea using both convenience and snowball sampling methods. A higher proportion of male participants was found in the Korean panel than in the Chinese panel. Majority of the Korean participants stayed in China for less than 1 week, whereas the Chinese panel mostly stayed in Korea for 1–3 years. Also, more Chinese participants had experienced Haemul-pajeon, and the consumption frequency was also higher in the Chinese panel than that of the Koreans’ Cōngyóubĭng consumption frequency. Overall, the Chinese panel’s exposure level to Haemul-pajeon was higher than the Korean panel’s exposure level to Cōngyóubĭng. The Chinese panel’s longer period of staying in Korea was likely to increase their exposure to Haemul-pajeon. Therefore this should be considered when results are cross-culturally compared.

Table 1.

Consumer demographic

| Classification | Percent (%) | χ2 (df) | Significant probability (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean (n = 83) | Chinese (n = 97) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 33.7 | 18.6 | 5.416 (1) | 0.020 |

| Female | 66.3 | 81.4 | ||

| Age | ||||

| 19–29 | 100.0 | 97.9 | 1.731 (2) | 0.421 |

| 30–39 | 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 40–49 | 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 50–59 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Student | 98.8 | 91.8 | 5.028 (2) | 0.081 |

| Housewife | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Office worker | 1.2 | 4.1 | ||

| Part-timer | 0.0 | 4.1 | ||

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Stay period (of Korean in China/of Chinese in Korea) | ||||

| Less than 1 week | 83.1 | 0.0 | 176.551 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Less than 1 month | 15.7 | 0.0 | ||

| Less than 6 months | 1.2 | 6.2 | ||

| Less than 1 year | 0.0 | 9.3 | ||

| More than 1 year– less than 2 years | 0.0 | 38.1 | ||

| More than 2 year– less than 3 years | 0.0 | 33.0 | ||

| More than 3 years | 0.0 | 13.4 | ||

| Ethnic food experience (cōngyóubĭng to Korean/ pajeon to Chinese) | ||||

| Yes | 15.7 | 83.5 | 82.509 (1) | < 0.001 |

| No | 84.3 | 16.5 | ||

| Ethnic food intake frequencya (Korean / Chinese) | ||||

| Once to twice–more than once a day | 69.2 | 0.0 | 68.755 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Less than 5 times–more than once a week | 15.4 | 3.7 | ||

| More than 5 times– < 10 times/more than once a month | 15.4 | 46.3 | ||

| More than 10 times–once in 2–3 months | 0.0 | 28.0 | ||

| More than once a year | 0.0 | 8.5 | ||

| Hardly eat | 0.0 | 11.0 | ||

| Other | 0.0 | 2.4 | ||

aOnly participants who have had experience eating Cōngyóubĭng among Korean and Haemul-pajeon among Chinese were asked to respond to the intake frequency of the food

Consumer acceptance

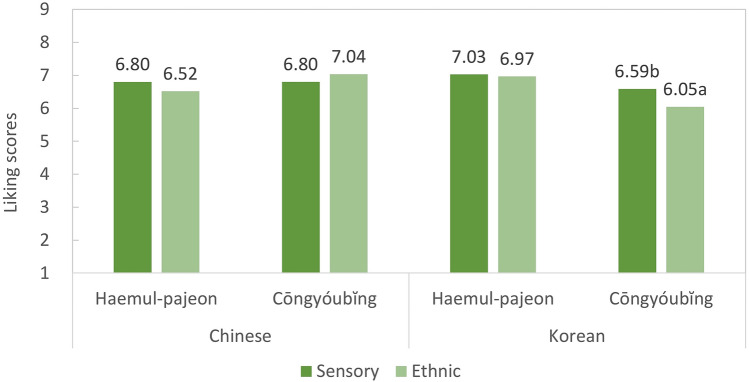

In this study, the results of ANOVA were explained focusing on the effect of context, the variable of main research interest. The effect of context was marginal (F1,1425 = 3.813, p = 0.051). Liking, in the sensory context (6.8 ± 1.7), was slightly higher than that in the ethnic context (6.7 ± 1.6). The results of the secondary and tertiary interactions were explained focusing the effect of context, the variable of main research interest. Among the interactions involving context, only nationality of the panel × sample × context significantly influenced liking (F1,1425 = 8.917, p = 0.003). Figure 1 shows that the effect of context appeared differently depending on nationality and sample. The Chinese panel’s liking for Haemul-pajeon and Cōngyóubĭng did not show any significant difference by context. However, the Koreans’ liking for Cōngyóubĭng was significantly higher in the sensory context than in the ethnic context. The Koreans panel’s liking for Haemul-pajeon was not affected by context. When the food from their home country was evaluated, both the Chinese and Korean panels’ liking was unaffected by both contexts. However when both panels evaluated liking for the food from the other country, liking tended to be negatively influenced by the ethnic context.

Fig. 1.

Mean liking scores of Haemul-pajeon and Cōngyóubĭng by nationality of panel, sample, and context

Context alone had a marginal influence on liking, but it rather influenced through its interaction with nationality and sample. The mechanism underlying this interaction may be related with familiarity to foods. Both panels’ liking for food from their respective home countries was unaffected by context, because the criteria to make a judgment on liking may have been stabilized over their previous exposure to the domestic food, thus remaining unchanged by context. In contrast, foreign food might be more susceptible to the influence of context. Hein et al., (2012) found that the effects of context on the liking of blackcurrant juice and apple juice varied by the sample type. Hedonic ratings decreased when context that is inappropriate or irrelevant in relation to the sample was evoked. Hersleth et al., (2015) observed that context that was more familiar to subjects increased consumer acceptance and purchase intent, resulting in better discrimination of liking among the samples. Based on these findings, it was initially assumed that the ethnic context would be perceived as more relevant to foreign food; therefore, the liking for foreign food can be positively influenced by the ethnic context. However, ethnic context seems to work differently from this assumption. Ethnic context might have interacted with foreign food to promote neophobic responses to unfamiliar foreign food, such as fear about the sensory characteristics of the sample (Tasci and Knutson, 2004), as well as doubt and uncertainty about what the “authentic taste of Korea/China” is, and whether the product performance would match up to this description. This interaction particularly had a greater effect on the Korean panel who were less exposed to Cōngyóubĭng (Table 1). Meanwhile, the Chinese panel, who had been more familiarized with Haemul-pajeon, was less influenced by ethnic context.

Emotional characteristics

One sample t test shows that all ratings of emotional terms were significantly different from zero (data not shown; p < 0.05); therefore, all RATA data were used for subsequent analyses. Sample, tasting, and context had significant global effects on emotional responses elicited by both the Korean and Chinese panels (Table 2). In addition, secondary and tertiary interaction effects (sample × context, sample × tasting, and sample × tasting × context) were also significant for both Koreans and Chinese. The tasting × context interaction was only significant in the Korean panel’s results (Table 2). Looking at the values of Wilk’s lambda as presented in Table 2, sample, tasting, and their interaction mostly contributed to the total variance of the emotional responses. Context and its secondary and tertiary interactions contributed less to the total variation than sample and tasting, but they significantly influenced emotional responses globally. Again, results are discussed mainly focusing on the effects involving context.

Table 2.

Wilks’ λ and significant probability associated with effects of consumer, sample, tasting, context and interactions between four factors on RATA test of emotions by Chinese and Korean consumer groups

| Wilks’ λ | Significant probability (p) | |

|---|---|---|

| Chinese | ||

| Sample | 18.159 | < 0.001a |

| Tasting | 16.366 | < 0.001 |

| Context | 2.198 | 0.006 |

| Sample × context | 2.045 | 0.012 |

| Tasting × context | 1.561 | 0.080 |

| Sample × tasting | 4.347 | < 0.001 |

| Sample × tasting × context | 2.201 | 0.006 |

| Korean | ||

| Sample | 23.248 | < 0.001 |

| Tasting | 17.452 | < 0.001 |

| Context | 7.130 | < 0.001 |

| Sample × context | 8.207 | < 0.001 |

| Tasting × context | 2.867 | 0.001 |

| Sample × tasting | 11.879 | < 0.001 |

| Sample × tasting × context | 3.105 | < 0.001 |

aSignificant probability smaller than 0.05 were highlighted in bold

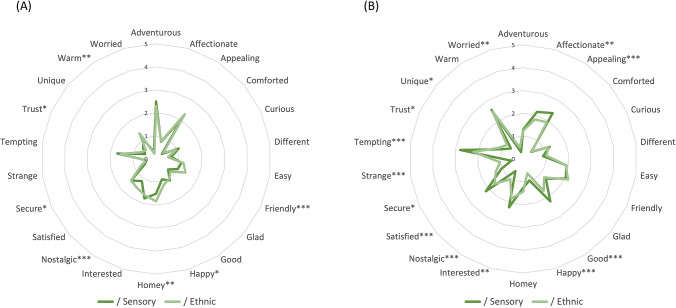

The main effect of context

Context had a significant effect on the Chinese panel’s evaluation of friendly, happy, homey, nostalgic, secure, trust, and warm (“Appendix 1”). Those terms were all induced more strongly in the ethnic context (Fig. 2A). Context had a significant effect on the Korean panel’s rating of affectionate, appealing, good, happy, interested, nostalgic, satisfied, secure, strange, tempting, trust, unique, and worried (“Appendix 2”). Affectionate, appealing, good, happy, interested, satisfied, and tempting were more strongly induced in the sensory context, and nostalgic, secure, strange, trust, unique, and worried were more strongly induced in the ethnic context (Fig. 2B). Overall, the ethnic context increased emotions with neutral-positive valence and neutral-low arousal, such as nostalgic, secure, or trust, in both Chinese and Korean panels. Context emphasizing “the authentic taste of China/Korea” may have evoked a safe and reliable feeling. Sensory context particularly influenced the Korean panel’s emotion, mostly those with positive valence and low arousal. However, sensory context also increased emotions with high arousal, such as interested and tempting. This implies that sensory context could evoke more interest in foods in Koreans, and possibly increase their consumption motive.

Fig. 2.

Differences in RATA ratings between two contexts by A Chinese panel and B Korean panel (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ANOVA)

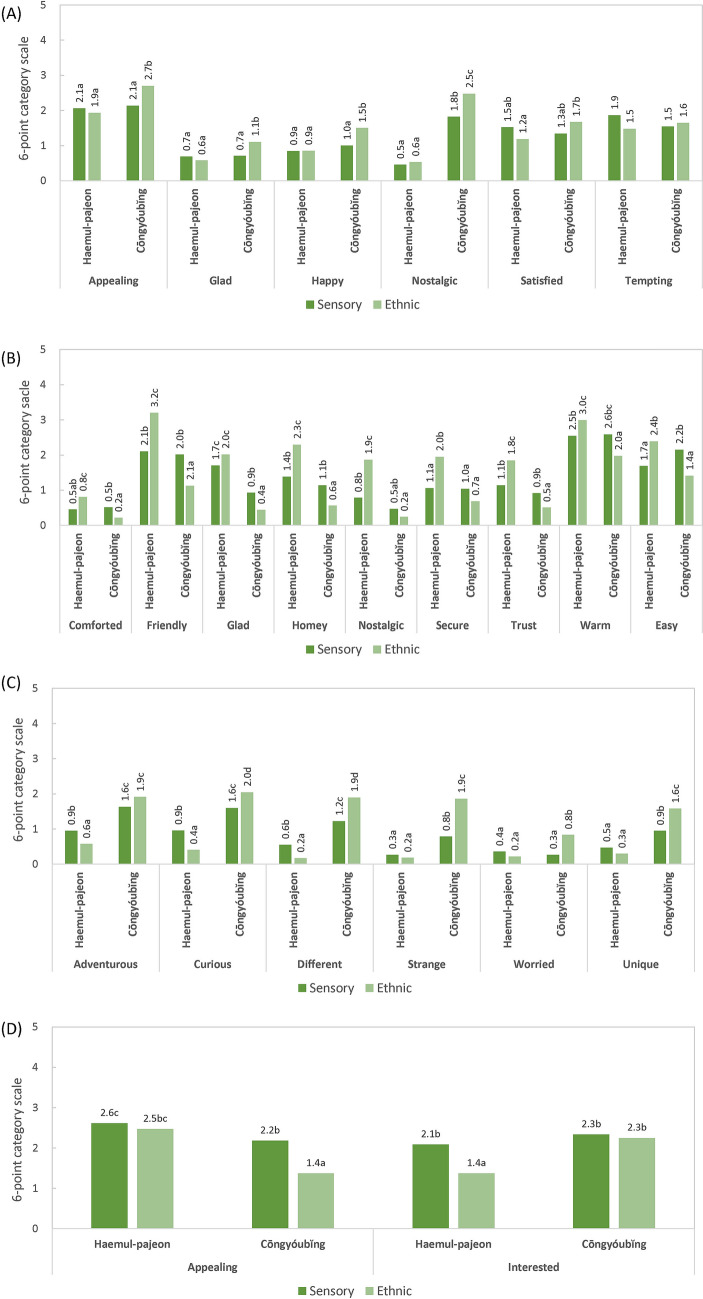

The secondary interaction effects

The interaction of sample × context had a significant effect on the Chinese panel’s evaluation of appealing, glad, happy, nostalgic, satisfied, and tempting (“Appendix 1”). These terms have positive valence and neutral or lower arousal (Kim and Hong, 2020). Appealing, glad, happy, and nostalgic were induced significantly stronger for Cōngyóubĭng in the ethnic context than in the sensory context. However, the emotions elicited for Haemul-pajeon did not differ much between the ethnic and sensory contexts (Fig. 3A). Although not significant, under the ethnic context, satisfied and tempting tended to be more weakly evoked from Haemul-pajeon but more strongly evoked from Cōngyóubĭng.

Fig. 3.

A Chinese panel’s ratings of emotion RATA of sensory and ethnic context by sample, and B, C, D Korean panel’s ratings of emotion RATA of sensory and ethnic context by sample (different alphabet letters indicate significant difference at p < 0.05, Duncan’s multiple range test)

The sample × context interaction had a significant effect on more emotional terms elicited by Koreans than those by Chinese (“Appendix 2”). Terms with a positive valence and neutral/lower arousal potential, such as comforted, friendly, glad, homey, nostalgic, secure, trust, warm, and easy, were more strongly expressed in the ethnic context when evaluating Haemul-pajeon. However, when evaluating Cōngyóubĭng, the results under the ethnic and sensory context were similar, or the emotions were more weakly rated under the ethnic context than under the sensory context (Fig. 3B). Meanwhile, adventurous, curious, different, strange (with positive-neutral valence and high arousal), worried (with negative valence and high arousal), and unique (with neutral valence and arousal) were evaluated more strongly under the ethnic context for Cōngyóubĭng and under the sensory context for Haemul-pajeon (Fig. 3C). Appealing and interested were evaluated weaker when the ethnic context was presented in both Cōngyóubĭng and Haemul-pajeon. However, the difference in ratings between the two contexts was significantly bigger for appealing in Cōngyóubĭng and for interested in Haemul-pajeon (Fig. 3D).

Context influenced evocation of emotions with positive valence and low arousal when both Chinese and Korean panels evaluated the food from their home country but not foreign food. However, context had a different effect on evoking emotions according to nationality of the panel. The Chinese panel’s emotions were more strongly elicited when Cōngyóubĭng was rated in the ethnic context than in the sensory context, whereas the Korean panel’s emotions were more strongly evoked when Haemul-pajeon was rated in the sensory context than in the ethnic context. The context by sample interaction also affected emotions with high arousal, but only in the Korean panel’s emotion. These emotions were felt stronger when the domestic food was evaluated in the sensory context, and the foreign food was evaluated in the ethnic context. This difference in emotional responses to foreign foods between Korean and Chinese panels seems to be related with the fact that Korean panel were less familiar to the foreign food than Chinese panel. Exposure to unfamiliar stimuli might have generated alertness, which is related with emotions of high arousal.

Overall, context influences emotional responses to domestic food. Desmet and Schifferstein (2008) identified personal and cultural meaning as sources of food emotion. Vignolles and Pichon (2014) reported that sweet foods evoked joy, happiness, comfort, and positive food nostalgia due to their pre-established association with childhood enjoyment. Further, it has been suggested that familiarity to foods was closely related with context, thereby affecting emotional responses (Dorado et al., 2016; Sester et al., 2013; Spinelli et al., 2015). Therefore, both panels could have developed more associations between domestic food and a certain situation, compared with foreign food. However, the association between foods and context varied according to the nationality of the panels, suggesting that the same context may have different influences on liking and emotional responses, depending on the subjects’ cultural background. This suggests that the mechanism underlying the effects of context on emotions works differently from this study’s hypothesis, which stated that the appropriateness of context for a given food would drive positive emotions. Contrarily, it may be due to the strength of association between context and food, which is determined by familiarity and a certain degree of exposure, playing a bigger role in emotion elicitation for foreign and domestic foods.

Considering that the liking and emotional valence have a strong positive correlation (Cardello et al., 2012; Gutjar et al., 2015), the Korean panel’s result that positive emotions are reduced when evaluating Cōngyóubĭng in the ethnic context may have some relevance to the decreased liking in the same condition.

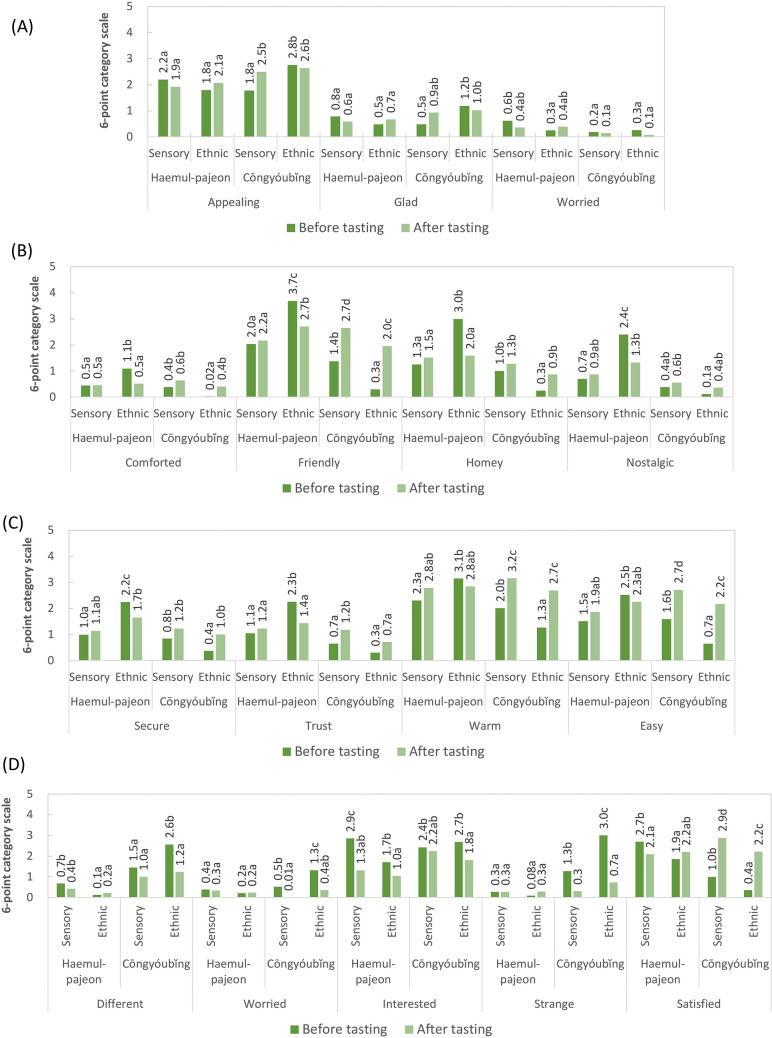

The tertiary interaction effects

The interaction of sample, tasting, and context had a significant effect on appealing, glad, and worried in the Chinese participants (“Appendix 1”). These feelings showed a tendency to decrease in the sensory context and increase in the ethnic context after tasting Haemul-pajeon, although this was not significant; however, they were evoked stronger in the sensory context and weaker in the ethnic context after tasting Cōngyóubĭng (Fig. 4A). Appealing had a particularly significant increase after tasting Cōngyóubĭng in the sensory context.

Fig. 4.

Differences in A Chinese emotional responses B, C, D Korean emotional responses by context, tasting and sample, (different alphabet letters indicate significant difference at p < 0.05, Duncan’s multiple range test)

The same three-way interaction affected more emotional terms elicited by Koreans than those by Chinese (“Appendix 2”). Throughout this study, the Koreans’ emotional responses tended to be more susceptible to the effects of various factors than the Chinese panel’s emotional responses. These differences should be investigated in future studies as to whether they are due to cultural differences or experimental conditions. When sensory context was presented for Haemul-pajeon, comforted, friendly, homey, nostalgic, secure, trust, warm, and easy did not show any significant difference or tended to increase slightly (but not significantly) after tasting, but those emotions were significantly increased in the ethnic context (Fig. 4B, C). When Cōngyóubĭng was evaluated under both sensory and ethnic contexts, the aforementioned emotions increased (Fig. 4B, C). When Koreans evaluated Haemul-pajeon, negative-neutral emotions with high arousal potential, such as different, worried, and strange, did not significantly differ in both the sensory and ethnic contexts before and after tasting (Fig. 4D). In contrast, these emotions were significantly decreased after tasting Cōngyóubĭng, regardless of context. Interested decreased after tasting both samples in both contexts, but the decrease in rating was bigger when Haemul-pajeon was tasted in the sensory context, and the same result was observed when Cōngyóubĭng was tasted in the ethnic context. Positively-valenced satisfied significantly decreased after tasting Haemul-pajeon under the sensory context, but increased slightly, although not significantly, under the ethnic context. When Cōngyóubĭng was evaluated in both sensory and ethnic contexts, satisfied was significantly increased after tasting (Fig. 4D).

Tasting generally increased positive emotions when the foreign food was rated in the ethnic context, but they were decreased when the domestic food was evaluated in the sensory context. Koreans tended to feel negative (worried) or high arousal emotions (different, strange) less strongly after tasting both the domestic and foreign foods than before tasting, but the reduction was greater in foreign food. Also, the Korean panel became less interested after tasting the domestic food in the sensory context and the foreign food in the ethnic context. Koreans were found to feel less satisfied after tasting the domestic food in the sensory context, but they became more satisfied after tasting the foreign food in both contexts.

The results of the present study imply that the foreign food–ethnic context condition strengthened the uncertainty of the unfamiliar foreign food, as well as the interest in it. However, when the food was actually tasted, such feelings were reduced. It is assumed that relief from the alertness regarding unfamiliar foreign food consequently generated positive emotions with neutral arousal. As previously suggested (Fotaine & Scherer, 2013; Spinelli et al., 2015), novelty dimension, which measures unpredictability and suddenness, may be important in interpreting emotions that are elicited from ethnic foods. This necessitates the inclusion of novelty dimensions in future studies of emotional responses to foreign foods. Meanwhile, the expectation formed through the domestic food-sensory context condition (“plenty of seafood” for Haemul-pajeon) seemed not to be met, thus decreasing positive feelings. This result is consistent with previous studies that reported an increase in positive emotions and decrease in negative emotions when expectations were met by actual performances (assimilation; Spinelli et al., 2015; Dorado et al., 2016). Context was reported to contribute to improved liking and generation of positive emotions, but only when their sensory and emotional experiences are coherent with the expectations (Danner et al., 2016; Piqueras-Fiszman and Jaeger, 2014a; 2014b; Spinelli et al., 2015).

The results of this study should be interpreted with care, because the panels differed in the level of exposure to the food used in the evaluation. The Chinese panel were familiar with Korean foods, since the consumer test was conducted using Chinese consumers who have resided in Korea. Because the familiarity of foods is one of the main factors determining preference for ethnic food (Hong et al., 2014), the level of experience in and knowledge of ethnic food could have influenced Korean and Chinese panel’s responses to foreign and domestic foods. Thus, it is difficult to conclude that the results of the evaluation represent the actual Chinese consumers’ liking and emotional responses to Korean food. A future on-site test in China is required to gain understanding about the effects of context on liking for ethnic foods, as well the emotion they evoke. Another limitation of the study is that the effect of each context was not compared with the control; therefore, identifying the size of effect with respect to no context condition was difficult. However, even though no context was presented, individual panelists may have considerably developed personal association for evaluation, which may result in more variations in baseline data. This should be investigated in future studies.

This study demonstrates the effects of context on emotional and hedonic responses, mainly through its interactions with the samples. Ethnic context alone increased positive and calming emotions, but when combined with foreign food, it intensified emotions with high arousal or negative valence. The actual experience gained by tasting mitigated such emotions. This interaction may be reflected in liking, showing a decrease in liking for foreign food evaluated under the ethnic context. Cultural difference and the degree of experience in the foreign food culture influenced the emotional responses. The outcomes of this study has practical implications that can contribute to establishing strategies to help consumers accept ethnic foods better. In line with this, it is necessary to explore in advance which contexts would be most appropriate for consumers when exporting ethnic foods abroad, taking into account the exposure and experience levels of consumers in the importing countries to the culture of the ethnic foods’ country of origin.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (IPET) through High Value-added Food Technology Development Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (Grant No. 315068-3).

Appendix 1: F-values and p-values associated with effects of sample, tasting, context and interactions between three factors on emotion RATA test by Chinese consumer

| Sample | Tasting | Context | Sample × context | Tasting × context | Sample × tasting | S × T × Cb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | |

| Adventurous | 6.027 | 0.016a | 106.908 | < 0.001 | 3.566 | 0.062 | 0.056 | 0.814 | 0.009 | 0.925 | 4.717 | 0.032 | 0.109 | 0.742 |

| Affectionate | 0.109 | 0.742 | 0.565 | 0.454 | 0.044 | 0.834 | 3.363 | 0.070 | 1.237 | 0.269 | 9.590 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.928 |

| Appealing | 11.261 | 0.001 | 1.475 | 0.227 | 3.062 | 0.083 | 7.497 | 0.007 | 0.309 | 0.580 | 1.475 | 0.227 | 7.724 | 0.007 |

| Comforted | 9.215 | 0.003 | 2.211 | 0.140 | 0.864 | 0.355 | 0.061 | 0.805 | 0.649 | 0.423 | 2.399 | 0.125 | 0.983 | 0.324 |

| Curious | 49.661 | < 0.001 | 135.015 | < 0.001 | 1.809 | 0.182 | 0.289 | 0.592 | 0.350 | 0.555 | 10.073 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Different | 30.852 | < 0.001 | 1.364 | 0.246 | 2.279 | 0.134 | 1.500 | 0.224 | 1.364 | 0.246 | 5.590 | 0.020 | 0.884 | 0.350 |

| Easy | 7.733 | 0.007 | 0.402 | 0.527 | 0.688 | 0.409 | 0.193 | 0.662 | 0.402 | 0.527 | 5.258 | 0.024 | 2.002 | 0.160 |

| Friendly | 123.251 | < 0.001 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 13.826 | < 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.916 | 0.138 | 0.711 | 2.212 | 0.140 | 0.341 | 0.560 |

| Glad | 8.777 | 0.004 | 0.528 | 0.469 | 2.450 | 0.121 | 7.502 | 0.007 | 0.378 | 0.540 | 0.612 | 0.436 | 7.199 | 0.009 |

| Good | 0.011 | 0.916 | 29.183 | < 0.001 | 0.550 | 0.460 | 3.055 | 0.084 | 0.137 | 0.712 | 5.186 | 0.025 | 0.045 | 0.833 |

| Happy | 15.053 | < 0.001 | 12.827 | 0.001 | 5.941 | 0.017 | 5.701 | 0.019 | 0.633 | 0.428 | 26.249 | < 0.001 | 0.121 | 0.728 |

| Homey | 44.712 | < 0.001 | 0.324 | 0.571 | 8.926 | 0.004 | 0.650 | 0.422 | 1.295 | 0.258 | 0.324 | 0.571 | 1.295 | 0.258 |

| Interested | 4.121 | 0.045 | 27.857 | < 0.001 | 1.030 | 0.313 | 0.237 | 0.627 | 0.059 | 0.808 | 11.356 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.903 |

| Nostalgic | 285.001 | < 0.001 | 0.045 | 0.833 | 14.030 | < 0.001 | 8.728 | 0.004 | 2.850 | 0.095 | 0.003 | 0.958 | 2.675 | 0.105 |

| Satisfied | 1.707 | 0.194 | 29.441 | < 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.982 | 8.162 | 0.005 | 1.083 | 0.301 | 0.358 | 0.551 | 1.484 | 0.226 |

| Secure | 30.297 | < 0.001 | 0.135 | 0.714 | 4.246 | 0.042 | 0.230 | 0.632 | 2.965 | 0.088 | 0.007 | 0.933 | 1.613 | 0.207 |

| Strange | 29.435 | < 0.001 | 8.097 | 0.005 | 0.071 | 0.791 | 0.071 | 0.791 | 0.416 | 0.520 | 10.895 | 0.001 | 0.761 | 0.385 |

| Tempting | 0.373 | 0.543 | 2.765 | 0.100 | 1.340 | 0.250 | 3.998 | 0.048 | 1.872 | 0.174 | 6.273 | 0.014 | 1.244 | 0.267 |

| Trust | 8.056 | 0.006 | 2.397 | 0.125 | 5.393 | 0.022 | 1.203 | 0.276 | 2.201 | 0.141 | 0.504 | 0.480 | 0.266 | 0.607 |

| Unique | 38.023 | < 0.001 | 2.351 | 0.128 | 3.458 | 0.066 | 0.384 | 0.537 | 2.769 | 0.099 | 0.308 | 0.580 | 1.159 | 0.284 |

| Warm | 25.089 | < 0.001 | 5.091 | 0.026 | 7.828 | 0.006 | 0.130 | 0.719 | 3.423 | 0.067 | 0.521 | 0.472 | 0.588 | 0.445 |

| Worried | 17.118 | < 0.001 | 2.155 | 0.145 | 2.155 | 0.145 | 2.155 | 0.145 | 1.237 | 0.269 | 0.239 | 0.626 | 5.560 | 0.020 |

ap-value smaller than 0.05 were highlighted in bold

bS × T × C, three way interaction between sample, tasting and context

Appendix 2: F-values and p-values associated with effects of sample, tasting, context and interactions between three factors on emotion RATA test by Korean consumer

| Sample | Tasting | Context | Sample × context | Tasting × context | Sample × tasting | S × T × Cb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | |

| Adventurous | 106.892 | < 0.0011) | 57.986 | < 0.001 | 0.245 | 0.622 | 11.594 | 0.001 | 3.223 | 0.076 | 10.364 | 0.002 | 0.552 | 0.460 |

| Affectionate | 99.140 | < 0.001 | 0.366 | 0.547 | 9.832 | 0.002 | 1.092 | 0.299 | 0.148 | 0.701 | 29.659 | < 0.001 | 1.891 | 0.173 |

| Appealing | 43.961 | < 0.001 | 0.221 | 0.640 | 17.011 | < 0.001 | 8.548 | 0.004 | 2.137 | 0.148 | 71.531 | < 0.001 | 1.704 | 0.195 |

| Comforted | 12.954 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.807 | 0.167 | 0.684 | 19.511 | < 0.001 | 2.415 | 0.124 | 16.727 | < 0.001 | 6.022 | 0.016 |

| Curious | 120.585 | < 0.001 | 80.059 | < 0.001 | 0.273 | 0.602 | 23.255 | < 0.001 | 1.350 | 0.249 | 21.605 | < 0.001 | 3.457 | 0.067 |

| Different | 167.797 | < 0.001 | 27.118 | < 0.001 | 2.441 | 0.122 | 32.071 | < 0.001 | 2.051 | 0.156 | 19.021 | < 0.001 | 11.021 | 0.001 |

| Easy | 4.249 | 0.042 | 30.303 | < 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.866 | 33.592 | < 0.001 | 0.212 | 0.646 | 26.182 | < 0.001 | 4.249 | 0.042 |

| Friendly | 93.300 | < 0.001 | 21.666 | < 0.001 | 0.887 | 0.349 | 78.358 | < 0.001 | 2.694 | 0.105 | 70.922 | < 0.001 | 10.952 | 0.001 |

| Glad | 170.051 | < 0.001 | 1.449 | 0.232 | 1.006 | 0.319 | 19.480 | < 0.001 | 0.040 | 0.841 | 33.849 | < 0.001 | 1.145 | 0.288 |

| Good | 72.790 | < 0.001 | 3.320 | 0.072 | 28.011 | < 0.001 | 3.320 | 0.072 | 4.705 | 0.033 | 100.713 | < 0.001 | 2.350 | 0.129 |

| Happy | 58.092 | < 0.001 | 0.489 | 0.486 | 16.107 | < 0.001 | 1.856 | 0.177 | 0.066 | 0.797 | 32.571 | < 0.001 | 2.507 | 0.117 |

| Homey | 84.804 | < 0.001 | 0.346 | 0.558 | 2.370 | 0.128 | 47.799 | < 0.001 | 9.653 | 0.003 | 22.377 | < 0.001 | 21.850 | < 0.001 |

| Interested | 17.000 | < 0.001 | 35.703 | < 0.001 | 8.599 | 0.004 | 5.360 | 0.023 | 0.109 | 0.742 | 4.387 | 0.039 | 8.343 | 0.005 |

| Nostalgic | 145.043 | < 0.001 | 2.366 | 0.128 | 27.985 | < 0.001 | 66.284 | < 0.001 | 13.244 | < 0.001 | 16.724 | < 0.001 | 16.724 | < 0.001 |

| Satisfied | 29.870 | < 0.001 | 62.802 | < 0.001 | 21.076 | < 0.001 | 1.721 | 0.193 | 4.543 | 0.036 | 83.305 | < 0.001 | 5.021 | 0.028 |

| Secure | 34.910 | < 0.001 | 1.700 | 0.196 | 6.095 | 0.016 | 32.337 | < 0.001 | 1.293 | 0.259 | 11.266 | 0.001 | 5.048 | 0.027 |

| Strange | 166.872 | < 0.001 | 80.175 | < 0.001 | 34.101 | < 0.001 | 46.657 | < 0.001 | 10.833 | 0.001 | 101.739 | < 0.001 | 19.571 | < 0.001 |

| Tempting | 32.584 | < 0.001 | 0.520 | 0.473 | 33.971 | < 0.001 | 2.441 | 0.122 | 1.592 | 0.211 | 44.484 | < 0.001 | 0.708 | 0.403 |

| Trust | 114.107 | < 0.001 | 1.063 | 0.306 | 4.084 | 0.047 | 58.218 | < 0.001 | 14.712 | < 0.001 | 29.191 | < 0.001 | 9.065 | 0.003 |

| Unique | 71.456 | < 0.001 | 15.048 | < 0.001 | 4.841 | 0.031 | 15.048 | < 0.001 | 3.017 | 0.086 | 9.064 | 0.003 | 2.444 | 0.122 |

| Warm | 26.821 | < 0.001 | 53.127 | < 0.001 | 0.691 | 0.408 | 31.657 | < 0.001 | 1.803 | 0.183 | 40.066 | < 0.001 | 7.914 | 0.006 |

| Worried | 18.212 | < 0.001 | 37.595 | < 0.001 | 12.129 | 0.001 | 32.937 | < 0.001 | 2.312 | 0.132 | 34.073 | < 0.001 | 4.872 | 0.030 |

ap-value smaller than 0.05 were highlighted in bold

bS × T × C, three way interaction between sample, tasting and context

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Thee authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Seon-Ho Kim, Email: xorhdakd123@naver.com.

Jae-Hee Hong, Email: jhhong2017@snu.ac.kr.

References

- Cardello AV, Meiselman HL, Schutz HG, Craig C, Given Z, Lesher LL, Eicher S. Measuring emotional responses to foods and food names using questionnaires. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012;24:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardello AV, Meiselman HL. Contextual influences on consumer responses to food products. Vol. 2, pp. 3-67. In: Methods in consumer research. Ares G, Varela P (eds). Woodhead Publishing, Ltd., Duxford, UK (2018)

- Dalenberg JR, Gutjar S, ter Horst GJ, de Graaf K, Renken RJ, Jager G. Evoked emotions predict food choice. PLOS one. 2014;9:e115388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danner L, Ristic R, Johnson TE, Meiselman HL, Hoek AC, Jeffery DW, Bastian SEP. Context and wine quality effects on consumers’ mood, emotions, liking and willingness to pay for Australian Shiraz wines. Food Res. Int. 2016;89:254–265. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet PMA, Schifferstein HNJ. Positive and negative emotions associated with food experience. Appetite. 2008;50:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorado R, Chaya C, Tarrega A, Hort J. The impact of using a written scenario when measuring emotional response to beer. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016;50:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Redwood, CA, USA: Standford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine JJR, Scherer KR. The global meaning structure of the motion domain: Investigating the complementarity of multiple perspectives on meaning. pp. 106-125. In: Components of emotional meaning: A sourcebook. Fontaine JJR, Scherer KR, Soriano C (eds). Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK (2013)

- Gutjar S, Dalenberg JR, de Graaf C, de Wijk RA, Palascha A, Renken RJ, Jager G. What reported food-evoked emotions may add: a model to predict consumer food choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015;45:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hein KA, Hamid N, Jaeger SR, Delahunty CM. Effects of evoked consumption contexts on hedonic ratings: a case study with two fruit beverages. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012;26:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hersleth M, Monteleone E, Segtnan A, Næs T. Effects of evoked meal contexts on consumers’ responses to intrinsic and extrinsic product attributes in dry-cured ham. Food Qual Prefer. 2015;40:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JH, Park HS, Chung SJ, Chung L, Cha SM, Lê S, Kim KO. Effect of familiarity on a cross-cultural acceptance of a sweet ethnic food: a case study with Korean traditional cookie (Yackwa) J. Sens. Stud. 2014;29:110–125. doi: 10.1111/joss.12087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang G, Paik WK. Korean Wave as tool for Korea’s new cultural diplomacy. Adv. Appl. Sociol. 2012;2:196–202. doi: 10.4236/aasoci.2012.23026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Hong JH. Comparison of emotional terms elicited for Korean home meal replacement between Chinese and Koreans. Kor. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;52:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon DY. What is ethnic food? J. Ethnic Food. 2015;2:1. doi: 10.1016/j.jef.2015.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mak AH, Lumbers M, Eves A. Globalization and food consumption in tourism. Ann. Tourism Res. 2012;39:171–196. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meiselman HL. A review of the current state of emotion research in product development. Food Res. Int. 2015;76:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mordor Intelligence, Ethnic Foods Market—Growth, Trends and Forecasts (2019–2024). Available from: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/ethnic-foods-market. Accessed Nov. 26, 2019

- Park JH, Trust in Korean Foods … K-food is Booming in China. Economic Review 2016. Available from: http://www.econovill.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=287476. Accessed Nov. 22, 2017.

- Piqueras-Fiszman B, Jaeger SR. The impact of evoked consumption contexts and appropriateness on emotion responses. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014;32:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piqueras-Fiszman B, Jaeger SR. Emotion responses under evoked consumption contexts: a focus on the consumers’ frequency of product consumption and the stability of responses. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014;35:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piqueras-Fiszman B, Spence S. Sensory expectations based on product-extrinsic food cues: an interdisciplinary review of the empirical evidence and theoretical accounts. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015;40:165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Tuorila H. Simultaneous and temporal contextual influences on food acceptance. Food Qual. Prefer. 1993;4:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0950-3293(93)90309-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Vollmecke TA. Food likes and dislikes. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1986;6(1):433–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.002245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setser C, Dacremont C, Deroy O, Valentin D. Investigating consumers’ representations of beers through a free association task: a comparison between packaging and blind conditions. Food Qual. Pref. 2013;28:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shim HK, Lee CL, Valentin D, Hong JH. How a combination of two contradicting concepts is represented: the representation of premium instant noodles and premium yogurt by different age groups. Food Res. Int. 2019;125:108506. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli S, Monteleone E. Emotional responses to products. Vol. 1, pp. 261-296. In: Methods in consumer research. Ares G, Varela P (eds). Woodhead Publishing, Ltd., Duxford, UK (2018)

- Spinelli S, Masi C, Zoboli GP, Prescott J, Monteleone E. Emotional responses to branded and unbranded foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015;42:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tasci AD, Knutson BJ. An argument for providing authenticity and familiarity in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Leis. Marketing. 2004;11:85–109. doi: 10.1300/J150v11n01_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson DM, Crocker C. A data-driven classification of feelings. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013;27:137–152. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vignolles A, Pichon PE. A taste of nostalgia: links between nostalgia and food consumption. Qual. Market Res. Int. J. 2014;17:225–238. doi: 10.1108/QMR-06-2012-0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y. Food safety and social risk in contemporary China. J. Asian Stud. 2012;71:705–729. doi: 10.1017/S0021911812000678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]