Abstract

Background:

Inhaling 35% carbon dioxide induces an emotional and symptomatic state in humans closely resembling naturally occurring panic attacks, the core symptom of panic disorder. Previous research has suggested a role of the serotonin system in the individual sensitivity to carbon dioxide. In line with this, we previously showed that a variant in the SLC6A4 gene, encoding the serotonin transporter, moderates the fear response to carbon dioxide in humans. To study the etiological basis of carbon dioxide-reactivity and panic attacks in more detail, we recently established a translational mouse model.

Aim:

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether decreased expression of the serotonin transporter affects the sensitivity to carbon dioxide.

Methods:

Based on our previous work, wildtype and serotonin transporter deficient (+/–, –/–) mice were monitored while being exposed to carbon dioxide-enriched air. In wildtype and serotonin transporter +/– mice, also cardio-respiration was assessed.

Results:

For most behavioral measures under air exposure, wildtype and serotonin transporter +/– mice did not differ, while serotonin transporter –/– mice showed more fear-related behavior. Carbon dioxide exposure evoked a marked increase in fear-related behaviors, independent of genotype, with the exception of time serotonin transporter –/– mice spent in the center zone of the modified open field test and freezing in the two-chamber test. On the physiological level, when inhaling carbon dioxide, the respiratory system was strongly activated and heart rate decreased independent of genotype.

Conclusion:

Carbon dioxide is a robust fear-inducing stimulus. It evokes inhibitory behavioral responses such as decreased exploration and is associated with a clear respiratory profile independent of serotonin transporter genotype.

Keywords: Panic attacks, panic disorder, serotonin transporter, carbon dioxide

Introduction

Panic attacks (PAs) are highly prevalent in many psychiatric disorders but are most commonly associated with panic disorder (PD). PAs are sudden surges of intense fear or discomfort peaking within minutes. During this period, four or more specified symptoms such as palpitations, a feeling of choking, or dizziness develop (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

In humans, PAs can be reliably provoked in the laboratory by inhaling air enriched with carbon dioxide (CO2). Various concentrations of CO2 have been examined over the years. Exposure to a low concentration (5–7%) for up to 20 min elicits symptoms as seen in a state of general anxiety and is therefore nowadays considered to represent a model for generalized anxiety disorder (Ainsworth et al., 2015; Bailey et al., 2005, 2007), while a deep breath of 35% CO2 provokes the sudden symptoms and intense fear associated with PAs in patients with PD (for extensive review see Leibold et al., 2015). Interestingly, a comparably intense emotional response can be triggered in healthy individuals when using a higher dosage of CO2 (i.e. taking two vital capacity breaths of 35% CO2 instead of one as in PD patients) (Griez et al., 2007), suggesting a spectrum of CO2-sensitivity.

To study the molecular basis of CO2-sensitivity in depth, the use of CO2 as an experimental stimulus in animal models has gained increasing attention in recent years (D’Amato et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2012; Taugher et al., 2014; Vollmer et al., 2016; Winter et al., 2017; Ziemann et al., 2009). As it is not feasible to apply one or two vital capacity breaths of 35% CO2 in rodents as it is done in humans, a lower percentage of up to 20% is commonly used for 10–20 min to allow assessment of behavior in a testing box filled with CO2. Using this methodology, studies showed that CO2 elicits robust fear-related behavior in rodents. A major aim of such rodent research is the translation of findings to humans. However, it is uncertain how well behavioral assessments in rodents correspond to the self-reported experience in humans. To address this challenge we used CO2 as the experimental stimulus in both rodents and humans and went beyond the traditional outcome measurements by recording additional physiological parameters (Leibold et al., 2016). Next to the finding that CO2 induces a strong fear-related behavioral response in mice and humans alike, we showed comparable cardio-respiratory effects. In detail, we calculated and statistically compared effect sizes, taking into account that the frequency per minute varies between both species. This allowed us to perform a quantitative comparison to demonstrate that exposure to a low concentration of CO2 in rodents corresponds to the response to a 35% CO2 inhalation in humans. Therefore, while the paradigms are not identical, the comparable effects of the cardio-respiratory system in addition to the behavioral fear response suggests that this rodent model represents a model of panic and is a promising approach to bring closer research in rodents and humans.

The mechanisms of how CO2 causes fear and exerts effects such as respiratory stimulation are not fully understood. Under physiological conditions the concentration of CO2 and pH level within the body are maintained within a narrow range. Small fluctuations are not consciously perceived, while larger acute changes typically induce adaptive physiological responses, sensations such as breathlessness, feelings of arousal and panic, and avoidance behavior (Brannan et al., 2001; Diaper et al., 2011; Ziemann et al., 2009). Emotions, in turn, can influence breathing (Homma and Masaoka, 2008) and thereby affect the respiratory response to CO2. Chemoreceptors that detect changes in CO2/pH are located in the peripheral carotid bodies and throughout the entire brain. For instance, Mitchell et al. did groundbreaking work on identifying the location of CO2-chemosensitivity in the medulla (1963b) and showed that increased CO2 in this region mediates an increase in breathing (1963a). Later experiments showed that also the medullary retrotrapezoid nucleus (Guyenet and Bayliss, 2015), and subsets of serotonergic neurons in the medullary raphe nucleus and the dorsal raphe nucleus are pH-sensitive (Richerson, 2004). The retrotrapezoid nucleus receives excitatory serotonergic innervation from both of these raphe nuclei, which can shift the CO2 threshold and stimulate respiration (Guyenet and Bayliss, 2015; Mulkey et al., 2007). Particularly serotonin (5-HT) neurons of the medullary raphe nucleus have been associated with driving the respiratory response to CO2. In contrast, midbrain 5-HT neurons have been associated with arousal and anxiety (Richerson, 2004).

In line with these basic research findings, many studies in humans provided support for a role of the 5-HT system in emotional sensitivity to CO2. For instance, tryptophan depletion, a method to reduce brain 5-HT levels, increased the fear response to CO2 inhalation in PD patients and healthy individuals (Miller et al., 2000; Schruers et al., 2000; Schruers and Griez, 2003), whereas administration of a 5-HT precursor, increasing brain 5-HT levels, reduced the response (Schruers et al., 2002). Blocking the 5-HT transporter (5-HTT) and thereby increasing the extracellular availability of 5-HT also reduced the response to CO2 (e.g. Bertani et al., 1997; Perna et al., 2002; Schruers and Griez, 2004). Further, our group showed that the fear reaction to CO2 is moderated by a functional polymorphism in the transcriptional control region of the gene encoding the 5-HTT (polymorphism referred to as 5-HTT gene-linked polymorphic region, 5-HTTLPR). In brief, subjects homozygously carrying the long (L)-allele reported more fear than short (S)-allele carriers (Schruers et al., 2011). In line with this, we also reported a negative association between DNA methylation in the 5-HTT regulatory region and emotional CO2-sensitivity (Leibold et al., 2020).

Making use of our rodent model and as translational follow-up to our previous studies in humans, we here aimed to explore whether partial or complete loss of 5-HTT moderates the response to CO2. For this purpose, wildtype (WT), hetero- (+/–), and homozygous (–/–) 5-HTT knockout mice were exposed to CO2, while the response was examined in terms of fear-related behavior and by monitoring cardio-respiration. Based on the findings of our previous studies, we hypothesized that wildtype mice would show the strongest sensitivity to CO2.

Materials and methods

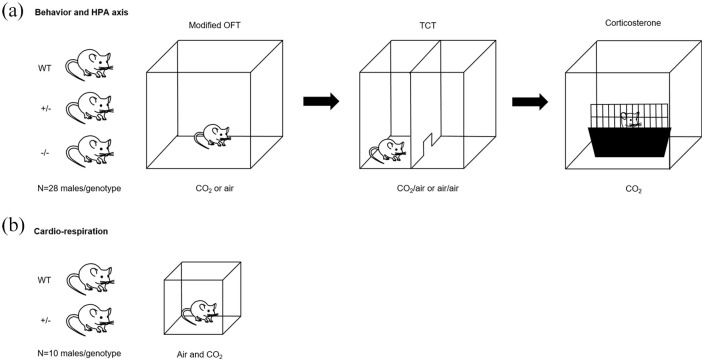

For overview see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of experimental design.

(a) Male wildtype (WT), serotonin transporter (5-HTT) heterozygous (+/–) and 5-HTT homozygous (–/–) knockout mice were first behaviorally tested in the modified open field test (OFT), while being exposed to either carbon dioxide (CO2) (n = 14/genotype) or air (n = 14/genotype), followed by a two-chamber test (TCT) in which a chamber was filled with CO2 and the other one with air or both chambers were filled with air. Then CO2-induced plasma corticosterone levels were determined. (b) Based on the results of these experiments, cardio-respiration was assessed in a new cohort of male WT and 5-HTT +/– mice. HPA: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal.

Fear-related behavior

Animals

Male 5-HTT deficient (Slc6a4tm1Kpl; 5-HTT+/– (n = 28); 5-HTT–/–(n = 28)) mice and their WT littermates (n = 28) were housed individually in ventilated cages within a temperature-controlled environment (21±1°C) and under a reversed day/night cycle (12 h light/12 h dark cycle). Standard rodent chow and water were provided ad libitum. From postnatal day 90 onwards, mice were subjected to fear-related behavioral tasks. For this purpose, per genotype 14 mice were assigned randomly to the experimental group (10% CO2) and 14 mice to the control group (air, 0% CO2): (a) WT mice exposed to air, (b) 5-HTT +/– mice exposed to air, (c) 5-HTT –/– mice exposed to air, (d) WT mice exposed to CO2, (e) 5-HTT +/– mice exposed to CO2, (f) 5-HTT –/– mice exposed to CO2. All procedures of this study were executed according to protocols approved by the Animal Ethics Board of Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Behavioral testing

Modified open field test (OFT)

All animals were first tested in the modified OFT. The OFT chamber consisted of a transparent Plexiglas square (50×50×40 cm), covered with a clear lid, allowing live monitoring of behavior during gas exposure. Gas was infused using an infusion port on the upper part of the box. Overpressure was prevented by two holes at the opposite site. In addition, two computer fans (5×5 cm, 26 dB), fixed to the lid, were used to ensure a homogenous concentration of the infused gas throughout the entire chamber. The CO2 concentration was constantly controlled using a 30% CO2 Sampling Data Logger (CO2 meter, Ormond Beach, Florida, USA).

Mice were placed in the center of the chamber that was pre-filled with either compressed air or 10% CO2 (premixed gas tanks, SOL Nederland B.V., Landgraaf, The Netherlands) depending on the experimental group. Movements were scored automatically with a computerized system (Ethovision Color Pro, Noldus, The Netherlands) for 20 min. For analysis purposes, the floor was subdivided into a 30×30 cm central zone, 10×10 cm corners, and 30×10 cm walls. Time spent in the different zones and total distance moved were analyzed. At the end of the trial, the boxes were cleaned thoroughly.

Behavioral testing was performed under low light conditions during the animals’ dark phase and by an investigator blind to genotype.

Two-chamber test (TCT)

After completing the modified OFT, mice were tested in the TCT. The apparatus consisted of two Plexiglas chambers (each 50×25 cm with 40 cm high walls) that were connected by an open door (3.5×3.5 cm) to allow free crossing, whilst limiting mixing of the gasses between chambers. Each chamber had a separate gas infusion port, a hole to prevent overpressure, and a computer fan (5×5 cm, 26 dB) to ensure a homogenous gas concentration throughout the chamber.

For mice assigned to air exposure, both chambers were pre-filled with air. For mice subjected to CO2 exposure, a chamber was pre-filled with 10% CO2 and the other one with air. The chamber that was filled with CO2 and the chamber in which mice were placed at the beginning of the test were randomized. The concentration of CO2 was continuously controlled using a 30% CO2 Sampling Data Logger (CO2 meter, Ormond Beach, Florida, USA; a steady state of 9% and 2% was reached in case of CO2 infusion). Movements, number of crossings, and time spent in each chamber were automatically scored with a computerized system (Ethovision Color Pro, Noldus, The Netherlands) for a period of 10 min. At the end of each trial, the box was thoroughly cleaned. As in the modified OFT, testing was done under low light conditions during the animals’ dark phase and by an investigator blind to genotype.

CO2-evoked freezing

In both behavioral tests, freezing was scored by a trained observer blind to exposure and genotype. Freezing was defined as absence of any movements apart from respiration and is considered to reflect fear-related behavior in rodents (Mongeluzi et al., 2003).

CO2-induced plasma corticosterone secretion

To assess the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responsiveness to CO2, plasma corticosterone levels were determined. Immediately after taking the mice from their home cage, the first blood sample was drawn via saphenous vein puncture (pre-CO2 level) using heparinized blood collection tubes (Microvette CB300, Sarstedt, Germany). Then, mice were returned to their home cage and exposed to 10% CO2 for 20 min, after which a second blood sample was taken (post-CO2 level). Blood samples were kept on ice and centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Plasma was collected and stored at −80°C until further processing. Blood corticosterone levels were analyzed using radioimmunoassay. An ImmunuChem Double antibody corticosterone 125I RIA Kit for rodents (MP Biomedicals, Orangeburg, New York, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Per sample 5 µL plasma was diluted in steroid diluents (1:100 for pre-CO2 and 1:200 for post-CO2 samples). Fifty μL of corticosterone 125I and 100 μL anti-corticosterone were added per 50 µL of diluted sample, after which the tubes were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Then, 250 µL precipitant solution was added to each sample and subsequently centrifuged at 2300 rpm for 15 min. After removing the supernatant the precipitation was counted in a Wizard gamma counter 2470 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

Cardio-respiratory response

In a next step, separate groups of WT and 5-HTT +/– knockout mice (background C57BL/6, n = 20/genotype, all male) were tested to assess the cardio-respiratory response to CO2. 5-HTT +/– mice might be considered the best model for the human 5-HTTLPR, because the S-allele is associated with a reduced expression of 5-HTT and not a complete deficiency as seen in 5-HTT –/– mice. Mice were housed in pairs of the same genotype within a temperature-controlled environment (25±1°C) and under reversed day/night cycle (12 h light/12 h dark cycle). Animals had access to standard rodent chow and water ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA. All assessments were made under low-light conditions during the dark phase. Mice were weighted on testing days. Breathing and heart rate were recorded simultaneously in a custom-made whole-body Plexiglas chamber (350 cm3). After habituation to the chamber for 30 min (with air infusion, all tanks from Airgas, Cheshire, Connecticut, USA), mice were exposed to air for 20 min, followed by 9% CO2 for 10 min. Flow rates were controlled using a digital flowmeter (0.4 L/min; WU-32446-33, Cole-Parmer, Inc., Hoffman Estates, Illinois, USA). Breathing was measured using a low pressure transducer (DC002NDR5; Honeywell International, Inc.; Minneapolis, USA) that was fitted to the recording chamber. Pressure oscillations induced by breathing were calibrated with 150 pulses/min (300 µL). Heart rate was measured non-invasively using two electrodes placed on the sides of the shaved thorax. The electrodes were connected to an amplifier (Model 440 Instrumentation Amplifier, Brownlee Precision Co., San Jose, California, USA). Ambient temperature (BAT-12 microprobe, Physiotemp Instruments, Inc., Clifton, New Jersey, USA) and relative humidity (HIH-4602-A sensor; Honeywell International, Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) within the chamber were recorded throughout the entire experiment. Immediately after the experiment, the animal’s temperature was measured rectally (BAT-12 microprobe, Physiotemp Instruments, Inc., Clifton, New Jersey, USA). Signals were digitized (PCI-6221 or USB-6008 National Instruments Corp., Austin, Texas, USA) and displayed in Matlab (version R2011b, Mathworks Co., Natick, Massachusetts, USA) with a custom-written acquisition program.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 25, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Statistical significance was considered as p < 0.05. Data are presented as mean + standard error of the mean (SEM). Behavioral data were analyzed using 3×2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess interaction effects of genotype (WT, 5-HTT +/– or 5-HTT –/–) and exposure (air or CO2), which were followed by separate ANOVA and post-hoc Bonferroni tests. For the TCT, additionally univariate analyses were used to assess genotype effects in the CO2 or air chamber (separate analyses). Corticosterone levels were ln-transformed before being analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA and separate ANOVAs for distinct time points. Physiological data of WT mice was published previously (Leibold et al., 2016), and here analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA on ln-transformed values. About 400 breathing-induced pressure changes of the second half of each gas exposure were analyzed. Artifacts due to moving, coughing, sniffing, and sighs were excluded. Animal temperature and body weight were considered to calculate tidal volume (amplitude) and ventilation. Heart rate was analyzed in terms of 30 s of the second half of each gas exposure and using the quick peaks gadget in Origin 9.0 (Origin Lab Corp., USA).

Results

Fear-related behavior

Modified OFT

In the modified OFT, significant overall effects of genotype (F(2,78) = 14.081, p < 0.001), exposure (F(1,78) = 552.442, p < 0.001), and a genotype × exposure interaction (F(2,78 = 18.996, p < 0.001) were observed on total distance moved (Figure 2(a)). Post-hoc analysis showed that within all three genotypes, CO2 exposure strongly reduced the distance covered compared to air exposure (p < 0.001). In addition, when exposed to air, 5-HTT –/– mice covered less distance in comparison with both WT and 5-HTT +/– mice (both p < 0.001). This effect was not present during CO2 exposure (both p = 1.000).

Figure 2.

Assessment of the behavioral performance in the modified open field test. (a) Under air exposure serotonin transporter (5-HTT) –/– mice covered less distance than mice of other genotypes. Exposure to carbon dioxide (CO2) significantly reduced the total distance moved in all genotypes. (b) During air exposure 5-HTT –/– mice spent less time in the center zone in comparison with wildtype (WT) mice. When exposed to CO2, only WT mice spent less time in the center compared to air exposure, no difference was found in 5-HTT +/– and 5-HTT –/– mice. (c) In all genotypes, CO2 exposure resulted in a robust freezing response compared to air exposure. Bars represent mean + standard error of the mean (SEM). +/–: heterozygous 5-HTT knockout mice; –/–: homozygous 5-HTT knockout mice. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; same letters indicate a group difference of p < 0.05.

With regard to time spent in center (Figure 2(b)), there was no overall genotype effect (F(2,78) = 1.953, p = 0.149), but a significant exposure effect (F(1,78 = 1.953, p = 0.008) and a genotype × exposure interaction (F(2,78) = 4.731, p = 0.011). Post-hoc follow-up revealed that CO2 exposure decreased the time spent in the center zone within WT mice only (p = 0.003). Furthermore, the duration spent was shorter in 5-HTT –/– air-exposed mice compared to WT air-exposed mice (p = 0.028), indicative of relatively more fear-related behavior in 5-HTT –/– mice. However, under CO2 exposure, 5-HTT –/– and 5-HTT +/– spent a comparable amount of time in the center as they did during air exposure (both p = 1.000), while WT mice spent less time in the center during CO2 exposure (p = 0.003). Comparing 5-HTT –/– and 5-HTT +/– mice with WT mice during CO2 exposure did not lead to a statistically relevant difference (both p = 1.000).

Moreover, regarding freezing (Figure 2(c)), overall analysis showed that there was no main effect of genotype (F(2,78) = 0.069, p = 0.933), while CO2 exposure was associated with alterations in freezing behavior (F(1,78) = 88.88, p < 0.001). The interaction genotype × exposure was not significant (F(2,78) = 1.503, p = 0.229). When exposed to CO2, mice showed a robust freezing response in comparison with air exposure (WT and 5-HTT +/–: p < 0.001, 5-HTT –/–: p = 0.002), reflecting fear-related behavior.

TCT

In the TCT, with one chamber filled with CO2 and one with air, or both filled with air, overall effects of genotype (F(2,78) = 5.647, p = 0.005), exposure (F(1,78) = 319.772, p < 0.001) and an interaction of genotype × exposure (F(2,78) = 3.266, p = 0.043) on total distance moved were present (Figure 3(a)). Post-hoc comparisons showed that in line with the modified OFT, when exposed to CO2, the distance covered was significantly reduced in all genotypes when compared to air exposure (p < 0.001). Again, under air exposure, 5-HTT –/– mice travelled less than WT mice (p = 0.007) and 5-HTT +/– mice (p = 0.015), a difference that was absent when exposed to CO2 (both p = 1.000).

Figure 3.

Assessment of the behavioral performance in the two-chamber test. (a) The total distance moved was strongly reduced under carbon dioxide (CO2) exposure in all genotypes. Serotonin transporter (5-HTT) –/– mice covered less distance than wildtype (WT) and 5-HTT +/– mice during air exposure. (b) Under CO2 exposure the number of crossings was significantly lower than during air exposure. (c) When exposed to air, no genotype differences were found. When exposed to CO2, a marked freezing response was observed only in WT and 5-HTT +/– mice compared to air-exposure. 5-HTT –/– mice froze less to CO2 than WT mice. (d) The ratio of time spent and freezing per chamber indicated that WT and 5-HTT +/– mice froze longer in the chamber filled with CO2 than 5-HTT –/– mice. No effect was found within the chamber filled with air. Bars indicate mean + standard error of the mean (SEM). +/–: heterozygous 5-HTT knockout mice; –/–: homozygous 5-HTT knockout mice. ***p < 0.001; a, b, d same letters indicate a group difference of p < 0.05; c, same letters indicate a group difference of 0.05.

Further, genotype did not significantly affect the number of crossings between the chambers (F(2,78) = 0.587, p = 0.559; Figure 3(b)). There was an overall exposure effect (F(1,78) = 147.743, p < 0.001), but not a genotype × exposure interaction (F(2,78) = 92.967, p = 0.549). Within all genotypes, the number of crossings was reduced under CO2 exposure compared to air exposure (p < 0.001). Regarding time spent in each chamber, when both chambers were filled with air, there was no overall effect of genotype (e.g. left chamber p = 0.653). Likewise, when one chamber was filled with CO2, there was no genotype difference in the duration spent in the CO2 chamber (F(2,39) = 1.425, p = 0.253). As in the modified OFT, overall, there was no genotype effect (F(2,789) = 1.272, p = 0.286), but a significant exposure effect (F(1,78) = 92.967, p < 0.001). Moreover, we observed a genotype × exposure interaction (F(2,78) = 5.382, p = 0.006) on the total freezing duration (Figure 3(c)). Post-hoc analyses showed that within genotype, both WT and 5-HTT +/– mice froze significantly more under CO2 exposure than when exposed to air (p < 0.001), which was not the case for 5-HTT –/– mice (p = 0.072). Between genotypes, 5-HTT –/– mice froze less to CO2 than WT mice (p = 0.034).

Evidently, the freezing duration influences the time spent in a particular chamber. To correct for this, for mice exposed to CO2 in one chamber and to air in the other chamber a ratio of time spent freezing relative to the total time spent in that particular chamber was calculated (Figure 3(d)). Within the CO2 chamber, an overall effect of genotype was found (F(2,37) = 4.623, p = 0.016). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the freezing/time spent ratio tended to be lower in 5-HTT –/– mice compared to WT (p = 0.067) and was significantly lower than in 5-HTT +/– mice (p = 0.022). No overall genotype effect was found in the other chamber, i.e. the one filled with air (F(2,30) = 0.776, p = 0.469).

CO2-induced plasma corticosterone secretion

Repeated measures ANOVA on plasma corticosterone levels showed a significant effect (F(1,78) = 334.286, p < 0.001) of increased levels after CO2 exposure for 20 min, but no time × genotype interaction (F(2,78) = 2.232, p = 0.114) (Figure 4). Analysis of the distinct time points showed no genotype differences in corticosterone levels (pre-CO2: F(2,78) = 1.423, p = 0.247; stress: F(2,78) = 1.841, p = 0.166). However, there was a significant effect of previous CO2 exposure in the behavioral tasks on pre-CO2 (F(1,78) = 5.707, p = 0.019) and post-CO2 corticosterone levels (F(1,78) = 17.929, p < 0.001), with higher levels when previously exposed to CO2.

Figure 4.

Plasma corticosterone secretion before and after exposure to 10% carbon dioxide (CO2) for 20 min. CO2 exposure strongly increased corticosterone levels in mice of all genotypes (exposure effect p = 0.002). Bars represent mean + standard error of the mean (SEM). +/–: heterozygous 5-HTT knockout mice; –/–: homozygous 5-HTT knockout mice; 5-HTT: serotonin transporter; WT: wildtype mice.

Breathing and heart rate recordings

In a next step, the cardio-respiratory response was assessed in WT and 5-HTT +/– mice only, i.e. excluding 5-HTT –/– mice, because these genotypes might represent the best model for the human 5-HTTLPR that is associated with a reduced and not complete deficiency of 5-HTT, and because re-analyzing the behavioral response of WT and 5-HTT +/– mice retained a significant genotype × exposure interaction (F(1,52) = 4.156, p = 0.047) on the time spent in the center zone of the modified OFT. WT animals spent less time in the center when exposed to CO2 compared to air-exposure (p = 0.001), while there was no difference in 5-HTT +/– animals (p = 1.000).

Analyzing breathing frequency, repeated measures analysis showed no main effect of genotype (F(1,37) = 1.887, p = 0.178) or genotype × exposure interaction (F(1,37) = 1.224, p = 0.276) (Figure 5(a)). However, a strong main effect of exposure was observed (F(1,37) = 123.192, p < 0.001), with increased breathing frequency during CO2 compared to air exposure. Similarly, overall, tidal volume was not affected by genotype (F(1,37) = 0.245, p = 0.623), but by exposure (F(1,37) = 392.665, p < 0.001) and a tendency towards an interaction of both (F(1,37) = 3.563, p = 0.067). CO2 appeared to increase tidal volume in comparison with air exposure (see Table 1 for mean + SEM). Furthermore, there was no overall effect of genotype (F(1,37) = 0.158, p = 0.693) and no genotype × exposure interaction (F(1,37) = 2.661, p = 0.111) on ventilation. However, a main effect of exposure was present F(1,37) = 340.193, p < 0.001), with increased ventilation when exposed to CO2 compared to air. With regard to heart rate, there was no genotype effect (F(1,36) = 0.508, p = 0.481), but overall, CO2 exposure decreased the mean heart rate compared to air exposure (F(1,36) = 54.219, p < 0.001) (Figure 5(b)). No interaction of genotype × exposure was observed (F(1,36) = 2.241, p = 0.143).

Figure 5.

Respiratory and cardiovascular monitoring during exposure to air and carbon dioxide (CO2). (a) Schematic representation of a 2 s epoch of pressure-induced changes to assess breathing frequency and tidal volume (amplitude) during inhaling air (top) and CO2 (bottom). CO2 strongly increased breathing frequency in comparison with air exposure. (b) Heart rate decreased during inhaling CO2. No genotype effect was present in any outcome measurement. Bars represent mean + standard error of the mean (SEM). +/–: heterozygous 5-HTT knockout mice; 5-HTT: serotonin transporter; WT: wildtype mice. ***p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Carbon dioxide (CO2)-induced changes in respiratory and cardiovascular measurements.

| Genotype | Breathing frequency (breaths/min) | Tidal volume (mL/g) | Ventilation (mL/min/g) | Heart rate (beats/min) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | CO2 | Air | CO2 | Air | CO2 | Air | CO2 | |

| WT | 263 (15) | 382 (14) | 0.06 (<0.01) | 0.10 (0.01) | 13.37 (1.29) | 37.97 (2.63) | 661 (13) | 554 (20) |

| 5-HTT +/– | 224 (17) | 354 (21) | 0.05 (<0.01) | 0.11 (0.01) | 11.64 (0.94) | 40.70 (2.82) | 677 (12) | 520 (23) |

5-HTT: serotonin transporter; 5-HTT +/–: heterozygous 5-HTT knockout mice; WT: wildtype mice.

Values represent mean (standard error of the mean (SEM)).

Discussion

As follow-up to our previous study in humans showing a differential self-reported fear response to CO2 depending on the 5-HTTLPR genotype (Schruers et al., 2011), we further investigated the relationship between chemosensitivity and the 5-HT system by exposing WT, 5-HTT +/–, and 5-HTT –/– mice to CO2. In line with our previous studies in humans (Leibold et al., 2016; Schruers et al., 2011) and mice (Leibold et al., 2016), CO2 induced robust fear-related behaviors and strongly activated the respiratory system. However, in contrast to our hypothesis, there were only minor effects of differential 5-HTT expression on behavior.

In humans, the use of CO2 as experimental panic-stimulus is well established in PD patients and, when using a higher dosage, also in healthy individuals (for review see Leibold et al., 2015). This is suggestive of the involvement of fundamental neurobiological mechanisms. Inhaling air enriched with CO2 is associated with an acute drop in brain pH (Schuchmann et al., 2006; Ziemann et al., 2008, 2009) that can trigger various adaptive responses, as such a pH drop can have life-threatening consequences. In this study, we investigated the responses to CO2 by using two behavioral tasks (modified OFT and TCT) and by assessing cardio-respiration. Generally, the OFT is considered an anxiety test, in which avoidance of the center zone (open zone) is one of the main outcome measurements. It has to be mentioned that anxiety is distinct from fear/panic and that different brain structures and behaviors are involved (Blanchard and Blanchard, 1990). Anxiety predominates when the distance to a threat is large, i.e. when there is a potential threat. This is associated with risk assessment and approach behavior. Fear dominates when the distance to a threat is small, i.e. when there is a direct threat. This leads to primitive survival responses. Conceptually, prefilling the OFT testing box with CO2 that reduces the pH within the body and thus causes a threat from the smallest distance possible, namely from within body, can be considered to elicit a state of fear/panic rather than anxiety. Further support for this notion is provided by our previous study in mice, in which we showed that that exposure to a low concentration of CO2 in rodents leads to cardio-respiratory effects corresponding to the ones evoked by a 35% CO2 inhalation in humans (Leibold et al., 2016). In the TCT, with one chamber being filled with CO2 and one with air, avoidance to an aversive stimulus is tested. It is assumed that mice spend more time in the chamber filled with air to avoid the effects of CO2 (Ziemann et al., 2009).

Examining the effects of CO2 in these tasks showed that CO2 induced a robust fear-related behavioral response in mice, in line with previous reports (Johnson et al., 2011, 2012; Leibold et al., 2016; Ziemann et al., 2009). However, unexpectedly, there were only minor effects of 5-HTT genotype. More specifically, total distance moved was strongly decreased in both tasks, independent of genotype. Likewise, the total duration of freezing, a correlate of fear and panic in mice (Mongeluzi et al., 2003; Ziemann et al., 2009), in the modified OFT and the number of crossings between compartments in the TCT were similarly affected in all genotypes. Exceptions are the duration spent in the center zone of the modified OFT, an outcome measurement that is relatively independent on locomotor activity, and freezing in the TCT. With regard to the duration spent in the center zone of the modified OFT, 5-HTT –/– mice show no decrease in time spent in the center zone during CO2 exposure compared to air exposure. This suggests an altered threat perception and/or altered coping strategy in mice carrying the full knockout. For instance, the fact that 5-HTT –/– mice already spent very little time in the center during air exposure could represent heightened aversion to the OFT itself in this genotype, leading to a ceiling effect. In the TCT, however, 5-HTT –/– mice spent less time freezing over the total time spent in the aversive compartment. This, again, could indicate that mice carrying the full knockout perceive CO2 differently or have an altered coping strategy. Furthermore, it cannot be excluded that the TCT is less aversive in comparison to the OFT, as the compartments are smaller. These observations are in line with previous work showing, e.g., that mice fully deficient of 5-HTT performed worse in the more stressful water maze test compared to WT and 5-HTT +/– littermates, while no differences were observed in Barnes maze (Karabeg et al., 2013).

Next to direct effects on animal behavior, we aimed to measure avoidance of CO2 as an aversive stimulus. In the TCT, animals had the option to leave the compartment filled with CO2. Unexpectedly, we did not observe any avoidance, in contrast to previous studies in mice, in which WT mice spent most of the time in the chamber filled with air (D’Amato et al., 2011; Ziemann et al., 2009). This discrepancy can be explained by the immense freezing response that we observed in the present study when CO2 was present, which seems to have prevented the animals from leaving the CO2 chamber. This notion is supported by the strongly reduced crossing frequency between both chambers in the presence of CO2 Ziemann et al. (2009) used 15% CO2 in this task in their previous study. In our study, a steady state of 9% CO2 was reached, which is lower than the previously used concentration of 15% CO2. In addition, care was taken to use an optimized methodological approach, including fans to homogenize the air, continuous measurement of the CO2 concentration, and a randomization regarding side of CO2 administration and side, in which mice were placed at the beginning of the test. Moreover, the chambers of our set-up were bigger compared to the set-up used by Ziemann et al. The combination of a larger box in our study and CO2 may have been a particularly aversive stimulus. Possibly, this led to a ceiling effect and prevented finding any subtle genotype differences under CO2 exposure. CO2 exposure is stressful in nature as shown by the observed increase in plasma corticosterone, which is in line with previous reports (D’Amato et al., 2011). This effect of CO2 is independent of genotype and suggests that differences in behavioral performance are not primarily dependent on HPA axis reactivity.

In addition, to studying the behavioral effects of CO2 exposure, also the effects on the cardio-respiratory system were explored. CO2 strongly activated the respiratory system with an increase in breathing frequency and tidal volume; heart rate decreased in comparison to air exposure. These results are consistent with those previously reported in, for example, freely moving rats (Annerbrink et al., 2003) and phrenic nerve recordings of anesthetized rats under CO2 exposure (Dumont et al., 2011). In the present study, effects were independent of genotype. To the best of our knowledge, little research has been done regarding examining the respiratory response to CO2 in mice deficient for 5-HTT or in humans related to the 5-HTTLPR genotype. Li and Nattie (2008) observed in their study that 5-HTT –/– males had a smaller increase in ventilation to CO2 than WT mice. 5-HTT +/– mice were not tested. The lack of a difference between WT and 5-HTT +/– mice in our study might be explained by 5-HT neurons sufficiently acting as chemosensors and initiating an adaptive response (Richerson, 2004), independent of 5-HT availability, or by a functionally insufficient difference in extracellular 5-HT availability to exert effects in this regard.

In addition to the potential explanations above that could contribute to the lack of clear differential 5-HTT expression effects in our study, another possibility is that several genetic and environmental vulnerability factors have to interact to lead to an altered functioning in the brain and a phenotype of heightened CO2-sensitivity. For instance, likewise to 5-HT neurons, many other neurons including noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus (LC) are activated by CO2/pH (Biancardi et al., 2008; Filosa et al., 2002; Pineda and Aghajanian, 1997). The LC receives major input from the medullary nucleus paragigantocellularis, a key region in cardio-respiratory regulation (Aston-Jones et al., 1986), and was shown to modulate the respiratory response to CO2 (Biancardi et al., 2008). Furthermore, LC neurons are involved in the behavioral response to stress (Stanford, 1995) and by projecting to nuclei of the limbic system these neurons likely mediate fear. Based on basic research findings like these and other research, it has been suggested that the central noradrenergic system, particularly the LC, is the common site for mediating the increases in fear and physiology to a 35% CO2 inhalation in humans (Bailey et al., 2003). It is noteworthy that the LC and the dorsal raphe nucleus are connected by extensive reciprocal connections (Kim et al., 2004). CO2 was shown to stimulate the release of 5-HT in the LC. By exerting inhibitory effects, 5-HT reduces the stimulatory effects of the LC on breathing in response to CO2 (de Souza Moreno et al., 2010). Contrary to this effect, in general, projections from the LC have excitatory effects on dorsal raphe nucleus neurons (Brown et al., 2002). These connections make it interesting to investigate, e.g. pharmacologically, whether disturbances in both systems might interact to express a phenotype of heightened CO2-sensitivity. While it is known that both 5-HT and noradrenergic neurons are sensitive to pH/CO2, it is unknown which neuronal molecule senses these changes and an alteration in that molecule could also contribute to a higher sensitivity to CO2. An interesting candidate is the acid-sensing ion channel 1a (ASIC1a). Genetic knockout of ASIC1a significantly blunts the CO2-induced behavioral effects (Ziemann et al., 2009) and antagonism normalizes the hyperreactivity to CO2 that is seen in a specific mouse model (Battaglia et al., 2019). Further, in addition to genetic factors, also their interaction with environmental stimuli shape behavioral phenotypes. For example, early life adversities such as maternal separation and repeated cross-fostering have been shown to increase the sensitivity to CO2 in rodents (Battaglia et al., 2019; D’Amato et al., 2011). Therefore, interplays of genetic vulnerabilities and environmental stressors could provide important insights for understanding the pathophysiology in more depth.

Some potential limitations of the present study should be kept in mind: As only male animals were tested no potential sex effects were examined. In humans, a higher prevalence of PD is reported in females (Dick et al., 1994; Gater et al., 1998), while CO2 studies did not consistently find this effect (Kelly et al., 2006; Leibold et al., 2013; Nardi et al., 2007; Nillni et al., 2012; Poonai et al., 2000). Therefore, more research into the effect of sex and menstrual cycle phase is warranted. Further, cardio-respiration was not assessed in 5-HTT –/– mice. As mice of this genotype were affected differentially in the behavioral tasks, physiological alterations associated with CO2 exposure should also be assessed in this genotype in future studies.

Conclusion

Overall, under CO2 exposure there was no effect of differential 5-HTT expression on physiological parameters and only minor interaction effects on behavior. Future research is needed that also addresses the interplays with other systems. These insights could contribute to a better understanding of the pathophysiology underlying CO2-sensitivity and eventually to develop better treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Denise Hermes, Barbie Machiels, Marjan Philippens, and Hellen Steinbusch for their technical assistance. They also thank the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG: CRC TRR 58 A5, CRU 125, CRC TRR 58 A1/A5, No. 44541416), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Grant No. 728018, Eat2beNICE), ERA-Net NEURON/RESPOND (No. 01EW1602B), ERA-Net NEURON/DECODE (No. 01EW1902), 5-100 Russian Academic Excellence Project, NIH/NINDS (K08 NS069667) and the Beth and Nate Tross Epilepsy Research Fund for their financial support.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: KPL served as a speaker for Eli Lilly and received research support from Medice, and travel support from Shire, all outside the submitted work. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: NL was financially supported by the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds, Germany, Daniel van den Hove (DvdH) by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG: CRC TRR 58 A5). GB was supported by NIH/NINDS K08 NS069667 and the Beth and Nate Tross Epilepsy Research Fund. KPL was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG: CRU 125, CRC TRR 58 A1/A5, No. 44541416), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant No. 728018 (Eat2beNICE), ERA-Net NEURON/RESPOND, No. 01EW1602B, ERA-Net NEURON/DECODE, No. 01EW1902 and 5-100 Russian Academic Excellence Project. The funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

ORCID iD: Nicole K Leibold  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2347-5423

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2347-5423

References

- Ainsworth B, Marshall JE, Meron D, et al. (2015) Evaluating psychological interventions in a novel experimental human model of anxiety. J Psychiatr Res 63: 117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Annerbrink K, Olsson M, Melchior LK, et al. (2003) Serotonin depletion increases respiratory variability in freely moving rats: Implications for panic disorder. Int J Neuropsychoph 6: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Ennis M, Pieribone VA, et al. (1986) The brain nucleus locus coeruleus: Restricted afferent control of a broad efferent network. Science 234: 734–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JE, Argyropoulos SV, Kendrick AH, et al. (2005) Behavioral and cardiovascular effects of 7.5% CO2 in human volunteers. Depress Anxiety 21: 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JE, Argyropoulos SV, Lightman SL, et al. (2003) Does the brain noradrenaline network mediate the effects of the CO2 challenge? J Psychopharmacol 17: 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JE, Kendrick A, Diaper A, et al. (2007) A validation of the 7.5% CO2 model of GAD using paroxetine and lorazepam in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol 21: 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M, Rossignol O, Bachand K, et al. (2019) Amiloride modulation of carbon dioxide hypersensitivity and thermal nociceptive hypersensitivity induced by interference with early maternal environment. J Psychopharmacol 33: 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertani A, Perna G, Arancio C, et al. (1997) Pharmacologic effect of imipramine, paroxetine, and sertraline on 35% carbon dioxide hypersensitivity in panic patients: A double-blind, random, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharm 17: 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancardi V, Bicego KC, Almeida MC, et al. (2008) Locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons and CO2 drive to breathing. Pflüg Arch Eur J Phy 455: 1119–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC. (1990) An Ethoexperimental Analysis of Defense, Fear and Anxiety. Dunedin: Otago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brannan S, Liotti M, Egan G, et al. (2001) Neuroimaging of cerebral activations and deactivations associated with hypercapnia and hunger for air. P Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 2029–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Sergeeva OA, Eriksson KS, et al. (2002) Convergent excitation of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons by multiple arousal systems (orexin/hypocretin, histamine and noradrenaline). J Neurosci 22: 8850–8859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato FR, Zanettini C, Lampis V, et al. (2011) Unstable maternal environment, separation anxiety, and heightened CO2 sensitivity induced by gene-by-environment interplay. PLoS One 6: e18637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Moreno V, Bicego KC, Szawka RE, et al. (2010) Serotonergic mechanisms on breathing modulation in the rat locus coeruleus. Pflüg Arch Eur J Phy 459: 357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaper A, Nutt DJ, Munafo MR, et al. (2011) The effects of 7.5% carbon dioxide inhalation on task performance in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol 26: 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick CL, Bland RC, Newman SC. (1994) Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in Edmonton. Panic disorder. Acta Psychiat Scand Suppl 376: 45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont FS, Biancardi V, Kinkead R. (2011) Hypercapnic ventilatory response of anesthetized female rats subjected to neonatal maternal separation: Insight into the origins of panic attacks? Resp Physiol Neurobi 175: 288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filosa JA, Dean JB, Putnam RW. (2002) Role of intracellular and extracellular pH in the chemosensitive response of rat locus coeruleus neurones. J Physiol 541: 493–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gater R, Tansella M, Korten A, et al. (1998) Sex differences in the prevalence and detection of depressive and anxiety disorders in general health care settings: Report from the World Health Organization Collaborative Study on psychological problems in general health care. Arch Gen Psychiat 55: 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griez EJ, Colasanti A, van Diest R, et al. (2007) Carbon dioxide inhalation induces dose-dependent and age-related negative affectivity. PLoS One 2: e987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. (2015) Neural control of breathing and CO2 homeostasis. Neuron 87: 946–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma I, Masaoka Y. (2008) Breathing rhythms and emotions. Exp Physiol 93: 1011–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PL, Fitz SD, Hollis JH, et al. (2011) Induction of c-Fos in ‘panic/defence’-related brain circuits following brief hypercarbic gas exposure. J Psychopharmacol 25: 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PL, Samuels BC, Fitz SD, et al. (2012) Activation of the orexin 1 receptor is a critical component of CO2-mediated anxiety and hypertension but not bradycardia. Neuropsychopharmacology 37: 1911–1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabeg MM, Grauthoff S, Kollert SY, et al. (2013) 5-HTT deficiency affects neuroplasticity and increases stress sensitivity resulting in altered spatial learning performance in the Morris water maze but not in the Barnes maze. PLoS One 8: e78238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MM, Forsyth JP, Karekla M. (2006) Sex differences in response to a panicogenic challenge procedure: An experimental evaluation of panic vulnerability in a non-clinical sample. Behav Res Ther 44: 1421–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MA, Lee HS, Lee BY, et al. (2004) Reciprocal connections between subdivisions of the dorsal raphe and the nuclear core of the locus coeruleus in the rat. Brain Res 1026: 56–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold NK, van den Hove DL, Esquivel G, et al. (2015) The brain acid-base homeostasis and serotonin: A perspective on the use of carbon dioxide as human and rodent experimental model of panic. Prog Neurobiol 129: 58–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold NK, van den Hove DL, Viechtbauer W, et al. (2016) CO2 exposure as translational cross-species experimental model for panic. Transl Psychiat 6: e885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold NK, Viechtbauer W, Goossens L, et al. (2013) Carbon dioxide inhalation as a human experimental model of panic: The relationship between emotions and cardiovascular physiology. Biol Psychol 94: 331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold NK, Weidner MT, Ziegler C, et al. (2020) DNA methylation in the 5-HTT regulatory region is associated with CO2-induced fear in panic disorder patients. Eur Neuropsychopharm 36: 154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Nattie E. (2008) Serotonin transporter knockout mice have a reduced ventilatory response to hypercapnia (predominantly in males) but not to hypoxia. J Physiol 586: 2321–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller HE, Deakin JF, Anderson IM. (2000) Effect of acute tryptophan depletion on CO2-induced anxiety in patients with panic disorder and normal volunteers. Brit J Psychiat 176: 182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RA, Loeschcke HH, Massion WH, et al. (1963. a) Respiratory responses mediated through superficial chemosensitive areas on the medulla. J Appl Physiol (1985) 18: 523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RA, Loeschcke HH, Severinghaus JW, et al. (1963. b) Regions of respiratory chemosensitivity on the surface of the medulla. Regul Respiration 109: 661–681. [Google Scholar]

- Mongeluzi DL, Rosellini RA, Ley R, et al. (2003) The conditioning of dyspneic suffocation fear. Effects of carbon dioxide concentration on behavioral freezing and analgesia. Behav Modif 27: 620–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey DK, Rosin DL, West G, et al. (2007) Serotonergic neurons activate chemosensitive retrotrapezoid nucleus neurons by a pH-independent mechanism. J Neurosci 27: 14128–14138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardi AE, Valenca AM, Lopes FL, et al. (2007) Caffeine and 35% carbon dioxide challenge tests in panic disorder. Hum Psychopharm 22: 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nillni YI, Berenz EC, Rohan KJ, et al. (2012) Sex differences in panic-relevant responding to a 10% carbon dioxide-enriched air biological challenge. J Anxiety Disord 26: 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perna G, Bertani A, Caldirola D, et al. (2002) Antipanic drug modulation of 35% CO2 hyperreactivity and short-term treatment outcome. J Clin Psychopharm 22: 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda J, Aghajanian GK. (1997) Carbon dioxide regulates the tonic activity of locus coeruleus neurons by modulating a proton- and polyamine-sensitive inward rectifier potassium current. Neuroscience 77: 723–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poonai N, Antony MM, Binkley KE, et al. (2000) Carbon dioxide inhalation challenges in idiopathic environmental intolerance. J Allergy Clin Immun 105: 358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson GB. (2004) Serotonergic neurons as carbon dioxide sensors that maintain pH homeostasis. Nat Rev: Neurosci 5: 449–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schruers K, Esquivel G, van Duinen M, et al. (2011) Genetic moderation of CO2-induced fear by 5-HTTLPR genotype. J Psychopharmacol 25: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schruers K, Griez E. (2003) The effects of tryptophan depletion on mood and psychiatric symptoms. J Affect Disorders 74: 305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schruers K, Griez E. (2004) The effects of tianeptine or paroxetine on 35% CO2 provoked panic in panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol 18: 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schruers K, Klaassen T, Pols H, et al. (2000) Effects of tryptophan depletion on carbon dioxide provoked panic in panic disorder patients. Psychiatry Res 93: 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schruers K, van Diest R, Overbeek T, et al. (2002) Acute L-5-hydroxytryptophan administration inhibits carbon dioxide-induced panic in panic disorder patients. Psychiatry Res 113: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchmann S, Schmitz D, Rivera C, et al. (2006) Experimental febrile seizures are precipitated by a hyperthermia-induced respiratory alkalosis. Nat Med 12: 817–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford SC. (1995) Central noradrenergic neurones and stress. Pharmacol Ther 68: 297–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taugher RJ, Lu Y, Wang Y, et al. (2014) The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis is critical for anxiety-related behavior evoked by CO2 and acidosis. J Neurosci 34: 10247–10255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer LL, Ghosal S, McGuire JL, et al. (2016) Microglial acid sensing regulates carbon dioxide-evoked fear. Biol Psychiatry 80: 541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter A, Ahlbrand R, Naik D, et al. (2017) Differential behavioral sensitivity to carbon dioxide (CO2) inhalation in rats. Neuroscience 346: 423–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann AE, Allen JE, Dahdaleh NS, et al. (2009) The amygdala is a chemosensor that detects carbon dioxide and acidosis to elicit fear behavior. Cell 139: 1012–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann AE, Schnizler MK, Albert GW, et al. (2008) Seizure termination by acidosis depends on ASIC1a. Nat Neurosci 11: 816–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]