Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are potent mediators of the graft versus leukemia (GVL) phenomenon critical to the success of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo HCT). Central to calibrating NK effector function via their interaction with class I human leukocyte antigens (HLA) are the numerous inhibitory killer Ig-like receptors (KIR). The KIR receptors are encoded by a family of polymorphic genes, whose expression is largely stochastic and uninfluenced by HLA genotype. These features provide the opportunity to select hematopoietic cell donors with favorable KIR genotypes that confer enhanced protection from relapse via NK-mediated GVL. Over the last two decades, a large body of work has emerged examining the use of KIR genotyping to stratify potential donors based on anticipated NK alloreactivity. Overall, these results support KIR-based donor selection for patients undergoing allo HCT for a diagnosis of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Despite this, the underlying factors that control NK cell responsiveness are not completely understood, and opportunities remain to refine donor selection using NK cell receptor genotyping. In this review, we will summarize the relevant findings with respect to KIR genotyping as a selection parameter for allogeneic hematopoietic cell donors and address practical considerations with respect to KIR-based selection of donors for patients with myeloid neoplasia.

1.0. Introduction

Natural killer cells are lymphocytes defined by their innate capacity to recognize and exert cytotoxicity against malignant or virally infected cells without prior sensitization.[1–3] This attribute distinguishes NK cells from T and B cells, which rely on receptor gene rearrangement for antigen specificity and expansion of antigen-experienced clones to effect adaptive immunity. Recently, the discovery of “memory” populations of NK cells that form after pathogenic stimuli, as well as the recognition that NK cells play a role in recruiting and maintaining other lymphocytes at the immune reaction site, have blurred the line between the innate and adaptive immune systems.[4–7] It is clear that NK cells are a surprisingly diverse family of specialized cell types, responsible for protection from viral infection, maintenance of the placental immune barrier, and recognition of cells that have undergone malignant transformation.[8–10] This latter property has spurred significant interest in NK cells as an agent of cancer immunotherapy, either via adoptive transfer or in the context of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Central to NK cell immunity is the detection of cellular stress in target cells, whereby loss of HLA class I combined with increased expression of NK activating receptor ligands on the target cell tilts the NK cells towards cytotoxicity.[11–13] Discovery of the Ly49 receptor family in mice and the killer Ig-like receptor (KIR) family in humans led to the first understanding of how interaction between inhibitory receptors on the NK cell and HLA class I molecules on adjacent cells maintains NK tolerance to normal cells, but unleashes cytotoxicity abnormal cells with altered HLA expression.[14, 15] Many viral species induce HLA loss in infected cells as a mechanism for T-cell immune evasion, thus sensitizing the target cell to NK mediated immunity.[16] Cancer cells as well may downregulate or lose HLA class I expression [17–19], but readily upregulate HLA class I expression in a minimally inflamed setting [20, 21], causing NK cells in this setting to rely on increased activating signals to trigger cytotoxicity. Sensing immune pressure, malignant cells may then down-regulate NK activating receptor ligands.[22, 23] These observations provide compelling evidence for the narrow margin for cytotoxic response created by simultaneous inhibitory and activating interactions between the target cell and the NK cell. In this review, we will explore how natural variations in inhibitory and activating signaling can be used to manipulate the threshold for NK activation in the setting of HLA-expressing target cells.

Effectively the first cellular therapy to control cancer, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo HCT) exerts a graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect mediated by alloreactive donor lymphocytes. A growing body of clinical evidence supports a significant contribution of NK cells to the GVL phenomenon in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML)[24], and increasingly, NK cells have demonstrated potential as a platform for adoptive cellular therapies[25–28]. Adoptively transferred allogeneic NK cells thus far have demonstrated limited efficacy, however, in part due to poor in vivo persistence.[29] Providing a continuous renewal of allogeneic NK cells, allo HCT remains the most effective means by which to provide durable NK alloreactivity and disease control. Moreover, it is increasingly clear that promoting NK activation does not induce graft versus host disease (GVHD) in allo HCT recipients, offering the possibility of harnessing a GVL effect without inciting GVHD. The use of immunogenetic biomarkers, such as those encoding KIR and their HLA ligands, to predict NK alloreactivity is a cost-effective and increasingly available means in the selection of donors to improve tumor control and transplant outcomes.

2.0. KIR: a diverse receptor family responsible for calibrating NK cell responsiveness

KIR receptors are a diverse group of cell surface receptors represented by both inhibitory and activating isoforms. Collectively, KIR are central to the NK cell maturation process and are important in maintaining and calibrating NK cell effector function in the peripheral tissues.[30–32] Inhibitory and activating KIR receptors are encoded by 14 different genes clustered with pseudogenes in the leukocyte receptor complex on chromosome 19q13.4.[33] While a diversity of gene content can populate the KIR gene cluster, two broad haplotype groups exist: the canonical “A” haplotype with fixed KIR gene content enriched for genes encoding inhibitory KIR, and the variable “B” haplotype group, comprised of haplotypes diverse in number of KIR genes and rich in genes encoding activating KIR.[33, 34] Allelic polymorphism, particularly among the inhibitory KIR genes, lends an additional layer of diversity.[35] Considerable differences in KIR genotype therefore exist between individuals, both at the level of gene content and allelic identity. Importantly, because the genetic regions encoding KIR and their HLA ligands are located on distinct chromosomes and segregate according to classic Mendelian patterns of inheritance, individuals do not always inherit the genes encoding HLA ligands for their given KIR; and, likewise, others may exhibit HLA for which they lack the genes encoding cognate KIR. In the context of allo HCT donors, therefore, KIR genotype cannot be imputed from HLA genotype, and donors with similar HLA genotypes will frequently have very different KIR genotypes.

Interaction between inhibitory KIR and their cognate HLA ligands not only prevents auto-aggression of NK cells toward autologous cells, it is also critical for the “education” of NK cells for effector function, whereby cells expressing KIR for self-HLA ligands are more responsive to NK stimulation.[32] Expression of KIR is largely stochastic, leading to NK populations within the NK repertoire with widely differing capacities for response.[36, 37] The inhibitory KIR include KIR3DL1, which interacts with the Bw4 epitope on HLA-B and some HLA-A allotypes; KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3, which recognize the HLA-C group 1 allotypes (C1) characterized by Ser77/Asn80; and KIR2DL1, which recognizes the HLA-C group 2 allotypes (C2) characterized by Asn77/Lys80.

Educated NK cells, which express inhibitory KIR for autologous HLA class I, are far more reactive to target cells in both in vitro and in vivo models compared to uneducated NK cells, which express KIR for which the individual lacks the HLA ligand.[38–40] Even among educated NK cells, those with a high degree of inhibitory signal from self-HLA are even more capable of effector function against transformed or infected cells, but are also more easily inhibited upon engagement of cognate HLA ligand on the same target cell.[41, 42] It is important to note that under highly inflammatory conditions, uneducated NK cells can overcome this deficit to become reactive against target cells, contributing to the immune response.[43] While NK education is central to establishing an NK cell’s threshold for response, it is still “tunable” by alterations in the HLA environment, one aspect of a complex and still poorly understood process of establishing the response capacity of an NK cell.[44]

3.0. Clinical significance of HLA and KIR interaction in HLA-mismatched allo HCT

The clinical significance of donor KIR genotype diversity first became apparent in the context of HLA-haploidentical transplantation using CD34+-selected allograft products (Table 1).[45, 46] In this setting, it was reported that absence of donor KIR ligand in the recipient was associated with decreased relapse of myeloid neoplasia following allo HCT, fulfilling the “missing self” mechanism of NK activation. Isolated donor NK cells expressing cognate KIR for the missing donor KIR ligand in the patient demonstrated reactivity to recipient leukemia cells, supporting NK tumor toxicity due to missing-self and revealing the previously unrecognized contribution of NK cells to the graft versus leukemia (GVL) phenomenon.

Table 1:

| NK Cell Alloreactivity Models | Hypothesis | Example | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitory KIR | |||

| Missing Self | Donor has a KIR ligand that is missing in the recipient AND donor exhibits the cognate KIR. Loss of inhibitory signal to donor KIR+ NK cells in the recipient activates them for cytotoxicity. | HLA-C1/x, KIR2DL3+ donor used for HLA-C2 homozygous recipient (missing HLA-C1 ligand for KIR2DL3). | [45, 46, 93] |

| Missing Ligand | Donor and recipient lack an inhibitory KIR ligand, rendering donor NK cells expressing the cognate KIR to be uneducated. Uneducated NK cells can participate in GVL reaction if sufficiently activated. | Recipient is HLA-C1 homozygous, HLA-C2 homozygous, or HLA-Bw6 homozygous. Donor exhibits inhibitory KIR but lacks HLA ligand. | [55–57] |

| Education/inhibition | When an inhibitory KIR ligand is present, variation in the cognate inhibitory KIR allows for selection of donors, with KIR that exhibit weak inhibitory interaction. NK cells remain educated but are minimally inhibited and can offer maximum participation in GVL. | Recipient is HLA-Bw4–80I. Donor is selected for KIR3DL1-L, KIR allotypes with weak interaction for HLA-Bw4–80I. | [41, 42, 78] |

| Activating KIR | |||

| Haplotype based selection | KIR B-haplotypes have more activating receptors, potentially leading to lower threshold for activating cells in the NK repertoire. | Donors are selected for KIR B-haplotypes, particularly those donors with activating receptors in the centromeric portion of the haplotype. | [59–63, 94] |

| HLA-C1/KIR2DS1 based selection | KIR2DS1 educates NK cells via interaction with HLA-C2. Overstimulation with HLA-C2 “disarms” NK cells, rendering them hyporesponsive. | For HLA-CI/x recipients, donors exhibiting HLA-C1 and KIR2DS1 are selected. | [68–70, 78] |

The recent introduction of post-transplant administration of cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy) as a GVHD prophylaxis strategy has obviated the use of isolated hematopoietic progenitor cells in HLA-mismatched adult donor allo HCT. The underlying hypothesis of PT-Cy is to activate and then selectively eliminate alloreactive T-cells by withholding immune suppression for three days after the allograft infusion prior to administration of PT-Cy on days 3 and 4 post-transplant. Recently published data in PT-Cy recipients suggest that this strategy also eliminates alloreactive NK cells, potentially dampening the overall contribution of the NK repertoire to GVL.[47] It is important to note, however, that in this study a robust recovery of KIR+ NK cells was still protective from relapse. Together, these findings suggest that PT-Cy based GVHD prophylaxis may be improved with strategies that either promote NK immune reconstitution or supplement the NK repertoire with donor NK cells infused after PT-Cy. At the current time, the data are insufficient to support KIR-based selection of haploidentical related donors when using a PT-Cy based approach, outside of a clinical trial.

Umbilical cord blood (UCB)-derived progenitor cells are another graft source to facilitate HLA-mismatched allo HCT. The role of KIR ligand mismatching in the graft versus host (GvH) direction has been tested in several relatively large, retrospective studies, yielding inconsistent results.[48–51] For example, a retrospective study of 218 patients with acute leukemia undergoing single-unit UCB performed by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT)/Eurocord-NetCord consortium demonstrated protection from relapse in recipients that underwent HCT using a KIR ligand mismatched donor. Three other studies of similar size, however, did not identify a benefit from KIR-ligand mismatched UCB donors. Indeed, data from the single center study performed at the University of Minnesota suggested an association between KIR ligand mismatching in the GvH direction and increased acute GVHD in recipients of reduced intensity conditioned allo HCT from double UCB recipients.[51] Despite the association with increased GVHD, KIR ligand mismatching did not provide protection from relapse in this study. Finally, the impact of KIR allelic polymorphism on UCB allo HCT outcomes remains largely unexplored. Overall, significant heterogeneity of clinical and transplant-specific parameters in UCB allograft recipients limits broad conclusions from these collective results.

4.0. KIR-based selection of HLA-matched adult unrelated donors

Facilitated by the growth of volunteer donor registries, unrelated donor (URD) transplantation has increased dramatically over the past four decades.[46] Between 2013 – 2017, as reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) registry, 12,683 URD transplants were performed in the United States for the diagnosis of AML or MDS.[52] Allele matching for the HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, and HLA-DRB1 loci is now the standard of care to define an “8/8 HLA-matched” URD.[53] The likelihood of having an available 8/8 HLA-matched URD is highly dependent on the overall diversity of HLA haplotypes within the patient population, resulting in wide disparities of donor availability for any given patient.[54] Among 528 patients with AML who underwent a formal URD search at our center, 77 (14.6%) had only one evaluated URD whereas 389 (73.7%) patients had three or more URDs evaluated for allo HCT. These numbers illustrate the underlying reality of URD availability: many patients have no matched donors available, but among those that do have at least one URD available, most will have several donors from whom to choose.

URD transplants matched for HLA genotype are, by definition, also KIR-ligand matched, precluding donor NK alloreactivity due to missing-self activation. Most individuals lack at least one HLA ligand for their cognate KIR (e.g. individuals homozygous for HLA-C1 lack the HLA-C2 ligand for KIR2DL1). In the context of allo HCT, this so-called “missing ligand” circumstance leaves some donor NK cells uneducated but also uninhibited upon contact with malignant cells.[43] The realization that uneducated NK cells can induce a potent GVL effect led to the hypothesis that recipient missing-ligand may be beneficial in the context of allo HCT. Several large scale observational studies have demonstrated that recipients missing one of the KIR ligands among HLA-C1, -C2, or -Bw4 had lower incidence of relapse and improved relapse-free survival after HLA-matched allo HCT (Table 1).[55–57] Again, the observed benefit was confined to recipients with a diagnosis of AML, supporting the unique role of NK cells in the GVL effect against this disease.

4.1. Activating KIR-based donor selection: KIR haplotypes and KIR2DS1/HLA-C1

HLA genotype in individuals is fixed and therefore cannot be manipulated to induce missing self or missing ligand donor NK activation in HCT. In contrast, however, donor KIR genotypes can vary greatly, leading investigators to examine whether donor KIR genotypes might increase allogeneic NK response to leukemia in HCT. Among the two KIR haplotype groups, the KIR-haplotype A contains only one activating KIR gene, KIR2DS4, which is frequently represented by an allele encoding a truncated non-signaling mutant.[58] In contrast, the KIR haplotype-B group possesses a more diverse membership, with haplotypes containing up to six activating KIR genes, including KIR3DS1, KIR2DS1, KIR2DS2, KIR2DS3, KIR2DS4, and KIR2DS5. Although the ligands for many of the activating KIR remain unknown, a reasonable hypothesis posits that donors with B haplotypes may result in a global NK repertoire with a lower threshold for activation, increasing the likelihood of a successful GVL response, and preventing leukemia relapse following allo HCT. Several older retrospective studies using CIBMTR registry data support this hypothesis, with some evidence that donors with B haplotypes with the centromeric-residing KIR2DS2 (cenB) are associated with relapse protection, particularly donors homozygous for cenB (cenBB).[59–62] An evaluation of patients treated in the modern era (2010–2016), could still demonstrate an effect of KIR haplotype-B on AML relapse, but only in patients receiving non-myeloablative conditioning regimens.[59] A prospective study evaluating donor selection based on KIR haplotypes has been completed for unrelated donor transplantation (NCT01288222); while initial results suggest that KIR haplotype-based donor selection is feasible, efficacy results from this study are pending.[63] Finally, retrospective studies in UCB allo HCT did not identify an impact of UCB donor haplotype B content on unit dominance or transplant outcomes following double-unit UCB transplantation. [64, 65]

KIR2DS1, found in the telomeric portion of B-haplotypes, encodes the only activating KIR known to contribute to NK education.[38, 66] KIR2DS1+ NK cells are progressively hyporesponsive in the presence of increasing amounts of ligand HLA-C2 in the environment.[67] Consequently, KIR2DS1+ NK cells from HLA-C2 homozygous individuals are tolerized and hyporesponsive to an HLA-C2+ target.[68] Venstrom and colleagues found in 1,272 patients undergoing transplant for AML that the presence of KIR2DS1 in allo HCT donors was protective from relapse, but only in the context of HLA-C1/x donors and not in the context of HLA-C2 homozygous donors.[69] Interestingly, donor HLA-C2 homozygosity also reverses the beneficial effects of donor KIR B-haplotype independent of KIR2DS1, suggesting that an environment rich in HLA-C2 ligands is generally suppressive toward NK cells with activating KIR.[62, 69, 70]

Donor activating KIR may have impacts on transplant outcomes separate from AML relapse. Donors possessing KIR3DS1 were associated with protection from acute GVHD, but did not affect relapse in a population of 1,087 patients with AML undergoing HLA well-matched URD allo HCT.[71] An activating isoform of KIR3DL1, KIR3DS1 binds to HLA-F open conformers in lieu of HLA-Bw4, leading to an uneducated status and insensitivity toward HLA-Bw4 for KIR3DS1+ NK cells.[72]

4.2. KIR3DL1 allele-based donor selection

KIR3DL1 and HLA-B alleles encoding the Bw4 epitope are the most polymorphic of the KIR/KIR ligand pairs, and different pairings of each exhibit significant differences in NK education and strength of inhibition.[73–76] KIR3DL1 allotypes may be organized into biologically relevant subtype groups based on surface expression: KIR3DL1-h subtypes (such as those encoded by KIR3DL1*001, *002 and *015) are highly expressed on the NK cell surface; KIR3DL1-l subtypes (including those encoded by KIR3DL1*005 and *007) are weakly expressed on the NK cell surface; and the KIR3DL1-null allotype (encoded by KIR3DL1*004) are retained intracellularly (Figure 2).[73–77] KIR3DS1 is considered a KIR3DL1 activating variant that does not have measurable binding to HLA-Bw4. As a general principle, KIR3DL1-h subtypes encode receptors that bind with higher affinity to HLA-Bw4+ subtypes with Ile80 (Bw4–80I) compared to HLA-Bw4+ subtypes with Thr80(80T). Consequently, NK cells bearing KIR3DL1-h receptors are more sensitive to inhibition by target cells expressing Bw4–80I ligands. In contrast, NK cells bearing KIR3DL1-l subtypes demonstrate higher inhibition with Bw4–80T allotypes.[42] Finally, neither the KIR3DL1-n allotype nor KIR3DS1 is inhibited by HLA-Bw4 on the target cell. This range of NK education and inhibitability among the KIR3DL1 subtypes for the different HLA-Bw4 subtypes presents an opportunity for selecting donors whose KIR3DL1 receptors will signal the least inhibition upon encountering patient HLA-Bw4.

Figure 2:

Donor KIR3DL1 and recipient HLA-Bw4 subtype combinations, their effects on NK function, and their associations with outcomes following allo HCT for AML.

Two large-scale retrospective studies have examined the role of KIR3DL1/HLA-Bw4 subtype interactions in allo HCT (Table 1). The first was an analysis of 1,328 AML patients undergoing HCT from 9/10 and 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donors conducted by our group and facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program and CIBMTR.[41] In this population, donors with weakly interacting or low inhibition KIR3DL1-Bw4 subtype combinations were protective from relapse and beneficial for overall survival, even after adjustment for other KIR interactions. A more recent analysis conducted by Schetelig and colleagues in the German Cooperative Transplant Study Group and the Deutsches Register für Stammzelltransplantationen failed to demonstrate a low inhibition KIR3DL1/HLA-Bw4 benefit, or any other KIR-related benefit, in 2,222 patients transplanted for AML.[78] It is important to note that in the latter study, lower-intensity conditioning and the use of anti-thymocyte globulin were more common than in studies evaluating patients treated primarily in the United States. It is important to note that the above analyses only examined the contribution of HLA-B allotypes with the Bw4 KIR epitope, but several HLA-A allotypes also exhibit the Bw4 epitope. A recent study by van der Ploeg and colleagues demonstrated that the Bw4+ HLA-A allotype HLA-A*24 is capable of strong inhibition of KIR3DL1+ NK cells.[79] Furthermore, in 1,729 recipients of an HLA well-matched URD allo HCT, the combination of HLA-A*24 and donor KIR3DL1 was associated with increased incidence of AML relapse. These findings suggest that including the contribution of Bw4+ HLA-A allotypes may refine the discriminatory capability of this model in future analyses. At the current time, it is unclear whether KIR3DL1/HLA-Bw4 may be used as a predictive biomarker for donor selection. Results of a prospective study evaluating donor selection based on a tiered framework prioritizing KIR3DL1/HLA-Bw4 interactions (NCT02450708) will add some clarity to this issue.

5.0. The NKG2 family of receptors

Apart from KIR, members of the NKG2 cell surface receptors may also contribute to NK education. The inhibitory NKG2A and the activating NKG2C receptors form heterodimers with CD94, and the heterodimeric pairs bind HLA-E on target cells to convey their respective signals. NKG2A functions similarly to inhibitory KIR in that interaction with its HLA ligand contributes to NK cell education and inhibition.[30, 80] The availability of a blocking antibody to NKG2A and its prevention of interaction with HLA-E and the ensuing inhibitory signaling, presents an alternative pathway by which to recruit NKG2A+ NK cells for cytotoxicity.[81] Polymorphism in HLA-E or in its peptide, the leader sequence of HLA class I, may also influence clinical outcomes via NK cells expressing NKG2A.[82, 83] In a retrospective study involving 1,840 recipients of 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor allografts, Tsamadou and colleagues demonstrated that donor homozygosity for the more highly expressed HLA-E*01:03 allele is associated with decreased disease-free survival and increased treatment related mortality.[84] These results are conflicted by a smaller study conducted by Hosseini and colleagues, where HLA-E*01:03 homozygosity was associated with decreased relapse and improved disease-free survival.[85] Overall, further studies are needed to understand how HLA-E, and potentially NKG2A, genotypes can be used to guide donor selection for allo HCT before this approach can be used in clinical practice.

6.0. Practical considerations when using KIR to select unrelated donors

A common and practical concern for the transplant physician is whether a “good KIR” donor is available only at the expense of other parameters that may also influence transplant outcome, such as donor age, parity, or ABO blood type. A second consideration is whether KIR allele or gene typing will delay donor workup, thereby exposing the patient to increased risk of relapse. To address these questions, we prospectively type all HLA-matched/single-antigen mismatched URDs evaluated for patients undergoing allo HCT workup with a diagnosis of MDS or AML for KIR genes and KIR3DL1 subtype. Since 2013, our center has performed KIR genotyping typing for 2,079 potential donors for 527 patients. We found that for HLA-Bw4+ recipients, the probability of having a donor with low-inhibition KIR3DL1/HLA-Bw4 interaction was 43% if only one donor was available for typing but increased significantly to 79.6% if three donors were typed. Among HLA-C1+ recipients, the probability of having a KIR2DS1+ or a cenBB donor was 45% and 11%, respectively, if only one donor was typed, and increased to 69% and 22%, respectively, if three donors were typed. Importantly, there was no difference in the time from formal search initiation to date of transplant in patients with advantageous donors compared to those without advantageous donors. The median time at our center from search to transplant was 86.5 days (32 – 1408 days) in patients with low-inhibition KIR3DL1/HLA-Bw4 donors compared to 88 days (21 – 975 days) in patients with high or neutral inhibition donors. Furthermore, there was no difference in donor age or CMV seropositivity between these two groups. These results suggest that KIR genotyping can be integrated into the URD search without increasing time to transplant or altering other donor parameters that may be important to the treating clinician.

6.1. Where should we place KIR when selecting an unrelated donor?

Selection of unrelated donors is complicated by a wide diversity of factors that may guide the clinician’s choice. Recently, a CIBMTR study examined what donor-specific factors are most likely to influence outcomes in allo HCT.[86] In this analysis, which did not include donor KIR genotype, only donor age was predictive of survival outcomes. Other factors, such as donor parity, ABO, or CMV status could influence quality of life due to their impacts on transplant-specific outcomes, but none of them altered the key outcome of overall survival. The mixed data supporting KIR-based URD selection for patients with AML suggest that previously unrecognized factors may alter KIR-mediated NK effects. Indeed, some of these factors are only now being identified: NK alloreactivity due to missing self in haploidentical HCT is severely blunted in the age of post-transplant cyclophosphamide [47]; HLA-C2 homozygosity erases the effect of activating KIR on HCT outcomes [62, 69]; and idiosyncrasies of conditioning regimens may favor or diminish the impact of alloreactive NK cells.[59] As we continue to seek to identify additional factors that compromise NK alloreactivity, the available evidence indicates that an alloreactive NK benefit is not only possible, but that taking steps to capture this effect does not compromise outcomes.

Presently, there are no standardized therapeutic interventions for reducing the risk of relapse following HCT, a major cause of transplant failure that accounts for nearly 50% of late mortality.[87] Given the potential benefit of durable disease control and relapse prevention, KIR-based donor selection is an appropriate, cost-effective intervention to implement while we await results of prospective studies. Moreover, unlike other maintenance strategies, it does not require patient compliance and does not impose adverse effects.

7.0. Role of NK immunogenetics in tailoring adoptive cellular therapies

NK cells are a natural platform for development of immune effector cellular therapies (IECTs). Due to their lack of rearranged, HLA-specific cell surface receptor expression HLA-mismatched cells may be infused without the consequence of severe GVHD. A promising example of this approach was demonstrated by Liu and colleagues, who transfected UCB-derived NK cells with genes encoding a CD19 specific chimeric antigen receptor and IL-15, as well as an inducible caspase-9 suicide gene.[88] In an early phase clinical trial, these investigators reported an overall response rate of 73% in 11 patients with CD19+ malignancy treated with this cell product.[89] Donors were selected to maximize the potential of missing-self given the respective KIR ligand profile of the recipient, but the small number of patients treated precludes any conclusions as to whether this selection was beneficial. Similarly, Ciurea and colleagues did not find a benefit to KIR haplotype-based selection of donors used to generate a membrane-bound IL-21 ex vivo expanded haploidentical NK cell product used in conjunction with allo HCT from the same donor, when PT-Cy-based GVHD prophylaxis was used.[90] Lee and colleagues found a non-statistically significant benefit from both KIR haplotype B content and KIR-ligand mismatched donors with infusion of third-party haploidentical related donor NK cells prior to HLA-matched allo HCT.[91] Bachanova and colleagues did not find an association between KIR-ligand mismatch and response in patients with refractory AML treated with haploidentical NK cells with or without T-regulatory cell depleting IL-2/diphtheria toxin conjugate.[92] Romee and colleagues found that a cytokine induced memory-like NK cell, generated via brief activation step with IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18, were reactive against AML cell line targets in vitro regardless of expression of KIR.[28] These results collectively suggest that pro-inflammatory manipulation to engineered IECT products may overcome any inhibitory KIR-HLA signaling, obviating the need to select NK-IECT donors based on this parameter. More data from clinical trials are required to address this question.

8.0. Concluding remarks

The past three decades have witnessed a rapid increase in our understanding of NK cell biology, and in particular, the role of HLA class I and KIR in calibrating NK cell effector function. Following biologically based hypotheses, there are now multiple retrospective clinical studies that support the beneficial impact of KIR and HLA-based URD selection in the context of allo HCT. The most proximal goal of future work will to be to define how NK immunogenetics can be used in prospective donor selection, with the knowledge that other considerations will compete for priority in the choice of a final donor. Looking forward, the use of PT-Cy-based GVHD prophylaxis will likely increase in both HLA-matched and -mismatched URD, as will the use of haploidentical related donor allo HCT. A major challenge exists in developing methods to promote the survival and expansion of alloreactive donor NK cells in recipients receiving PT-Cy. Finally, NK cell-based IECTs will emerge to be delivered as independent therapies as well as in combination with allo HCT, and the interaction of KIR-HLA in promoting the activity of these cell products will need to be explored. Decades of advancements in donor-recipient HLA matching have led to a dramatic reduction in T-cell mediated transplant-related mortality. Whether we can now use our understanding of KIR receptors, a complex layer of human immunogenetics beyond HLA, to open a door to innate immunity and the promise of long-lasting tumor control is an open and exciting question.

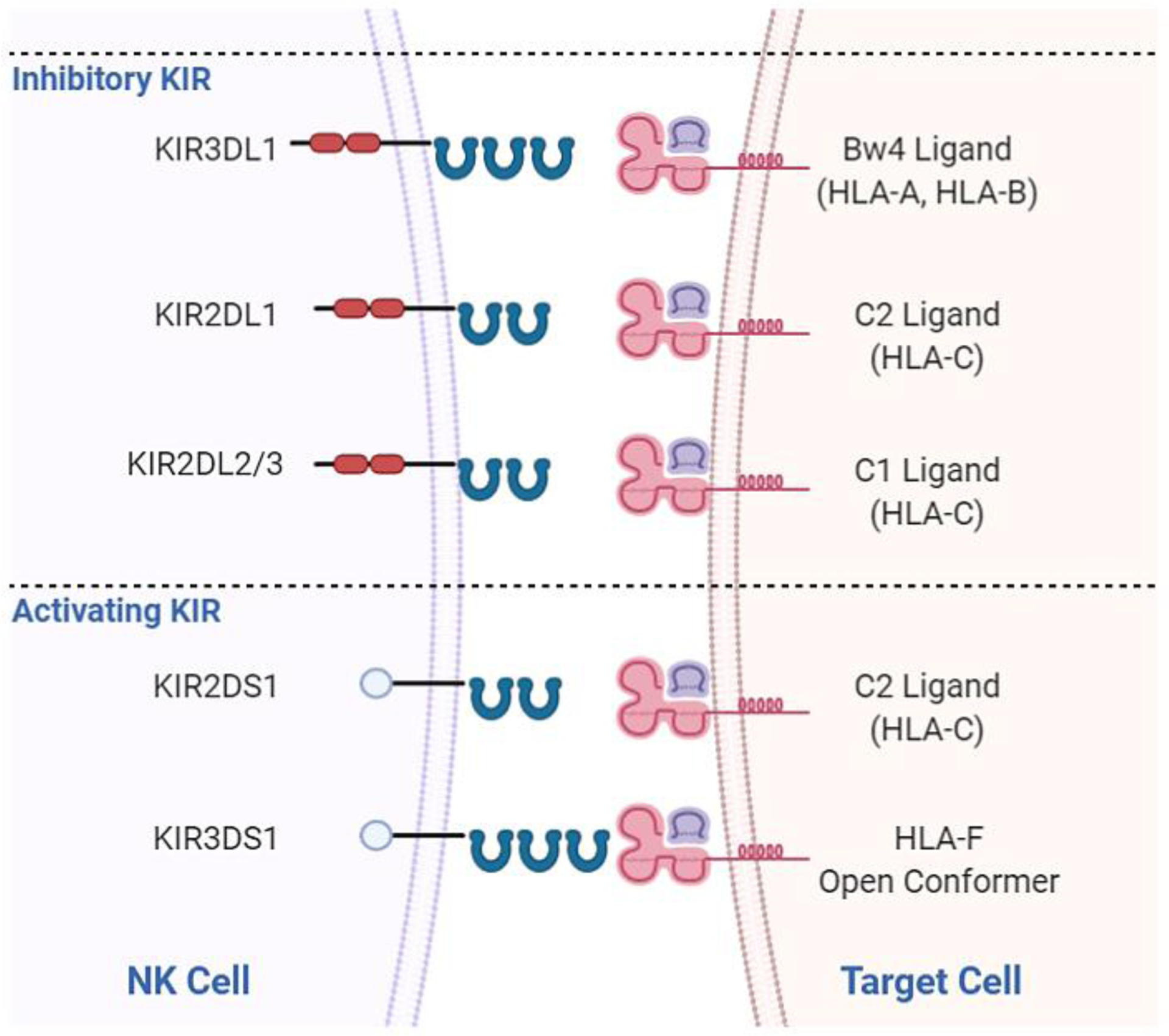

Figure 1:

Inhibitory and activating killer Ig-like receptors found to influence allo HCT outcomes and their cognate HLA ligands. KIR3DL1 receptors interact with HLA-B and HLA-A allotypes exhibiting the Bw4 epitope. KIR2DL1 interacts with HLA-C2 allotypes. KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 interact with HLA-C1 allotypes. KIR2DS1 interacts with HLA-C2 allotypes and KIR3DS1 interacts with HLA-F open conformers.[72]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest disclosure: BCS reports no conflict of interest relevant to this manuscript. KCH has a patent application on the KIR3DL1 multiplex PCR assay used for subtyping donors and the process of KIR and HLA based selection of hematopoietic stem cell used in this manuscript (CA2907068A1).

7.0 References

- 1.Herberman RB, Nunn ME, Lavrin DH. Natural cytotoxic reactivity of mouse lymphoid cells against syngeneic acid allogeneic tumors. I. Distribution of reactivity and specificity. International journal of cancer. 1975;16(2):216–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herberman RB, Nunn ME, Holden HT, Lavrin DH. Natural cytotoxic reactivity of mouse lymphoid cells against syngeneic and allogeneic tumors. II. Characterization of effector cells. International journal of cancer. 1975;16(2):230–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiessling R, Klein E, Pross H, Wigzell H. “Natural” killer cells in the mouse. II. Cytotoxic cells with specificity for mouse Moloney leukemia cells. Characteristics of the killer cell. European journal of immunology. 1975;5(2):117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raulet DH. Interplay of natural killer cells and their receptors with the adaptive immune response. Nature immunology. 2004;5(10):996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida O, Akbar F, Miyake T, Abe M, Matsuura B, Hiasa Y, et al. Impaired dendritic cell functions because of depletion of natural killer cells disrupt antigen-specific immune responses in mice: restoration of adaptive immunity in natural killer-depleted mice by antigen-pulsed dendritic cell. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2008;152(1):174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun JC, Lopez-Verges S, Kim CC, DeRisi JL, Lanier LL. NK cells and immune “memory”. J Immunol. 2011;186(4):1891–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nature immunology. 2008;9(5):503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammer Q, Rückert T, Romagnani C. Natural killer cell specificity for viral infections. Nature immunology. 2018;19(8):800–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moffett A, Colucci F. Uterine NK cells: active regulators at the maternal-fetal interface. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(5):1872–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kristensen AB, Kent SJ, Parsons MS. Contribution of NK Cell Education to both Direct and Anti-HIV-1 Antibody-Dependent NK Cell Functions. J Virol. 2018;92(11):e02146–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gleimer M, Parham P. Stress Management: MHC Class I and Class I-like Molecules as Reporters of Cellular Stress. Immunity. 2003;19(4):469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, Steinle A, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, et al. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science (New York, NY). 1999;285(5428):727–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cerwenka A, Baron JL, Lanier LL. Ectopic expression of retinoic acid early inducible-1 gene (RAE-1) permits natural killer cell-mediated rejection of a MHC class I-bearing tumor in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(20):11521–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahim MMA, Tu MM, Mahmoud AB, Wight A, Abou-Samra E, Lima PDA, et al. Ly49 receptors: innate and adaptive immune paradigms. Front Immunol. 2014;5:145-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dupont B, Hsu KC. Inhibitory killer Ig-like receptor genes and human leukocyte antigen class I ligands in haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Current opinion in immunology. 2004;16(5):634–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes PD, Grundy JE. Down-regulation of the class I HLA heterodimer and beta 2-microglobulin on the surface of cells infected with cytomegalovirus. The Journal of general virology. 1992;73 (Pt 9):2395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouwer RE, van der Heiden P, Schreuder GM, Mulder A, Datema G, Anholts JD, et al. Loss or downregulation of HLA class I expression at the allelic level in acute leukemia is infrequent but functionally relevant, and can be restored by interferon. Hum Immunol. 2002;63(3):200–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majumder D, Bandyopadhyay D, Chandra S, Mukhopadhayay A, Mukherjee N, Bandyopadhyay SK, et al. Analysis of HLA class Ia transcripts in human leukaemias. Immunogenetics. 2005;57(8):579–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrido F, Aptsiauri N. Cancer immune escape: MHC expression in primary tumours versus metastases. Immunology. 2019;158(4):255–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan S, Pestka S, Jubin RG, Lyu YL, Tsai YC, Liu LF. Chemotherapeutics and radiation stimulate MHC class I expression through elevated interferon-beta signaling in breast cancer cells. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e32542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christopher MJ, Petti AA, Rettig MP, Miller CA, Chendamarai E, Duncavage EJ, et al. Immune Escape of Relapsed AML Cells after Allogeneic Transplantation. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;379(24):2330–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paczulla AM, Rothfelder K, Raffel S, Konantz M, Steinbacher J, Wang H, et al. Absence of NKG2D ligands defines leukaemia stem cells and mediates their immune evasion. Nature. 2019;572(7768):254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.She M, Niu X, Chen X, Li J, Zhou M, He Y, et al. Resistance of leukemic stem-like cells in AML cell line KG1a to natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Cancer letters. 2012;318(2):173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farag SS, Fehniger TA, Ruggeri L, Velardi A, Caligiuri MA. Natural killer cell receptors: new biology and insights into the graft-versus-leukemia effect. Blood. 2002;100(6):1935–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller JS, Soignier Y, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, McNearney SA, Yun GH, Fautsch SK, et al. Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood. 2005;105(8):3051–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooley S, He F, Bachanova V, Vercellotti GM, DeFor TE, Curtsinger JM, et al. First-in-human trial of rhIL-15 and haploidentical natural killer cell therapy for advanced acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Advances. 2019;3(13):1970–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaffer BC, Le Luduec J-B, Forlenza C, Jakubowski AA, Perales M-A, Young JW, et al. Phase II Study of Haploidentical Natural Killer Cell Infusion for Treatment of Relapsed or Persistent Myeloid Malignancies Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(4):705–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romee R, Rosario M, Berrien-Elliott MM, Wagner JA, Jewell BA, Schappe T, et al. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells exhibit enhanced responses against myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(357):357ra123–357ra123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grzywacz B, Moench L, McKenna D Jr., Tessier KM, Bachanova V, Cooley S, et al. Natural Killer Cell Homing and Persistence in the Bone Marrow After Adoptive Immunotherapy Correlates With Better Leukemia Control. Journal of immunotherapy (Hagerstown, Md : 1997). 2019;42(2):65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brodin P, Lakshmikanth T, Johansson S, Kärre K, Höglund P. The strength of inhibitory input during education quantitatively tunes the functional responsiveness of individual natural killer cells. Blood. 2009;113(11):2434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anfossi N, André P, Guia S, Falk CS, Roetynck S, Stewart CA, et al. Human NK cell education by inhibitory receptors for MHC class I. Immunity. 2006;25(2):331–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S, Poursine-Laurent J, Truscott SM, Lybarger L, Song YJ, Yang L, et al. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. 2005;436(7051):709–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu KC, Chida S, Geraghty DE, Dupont B. The killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) genomic region: gene-order, haplotypes and allelic polymorphism. Immunological reviews. 2002;190:40–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uhrberg M, Valiante NM, Shum BP, Shilling HG, Lienert-Weidenbach K, Corliss B, et al. Human diversity in killer cell inhibitory receptor genes. Immunity. 1997;7(6):753–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.IPD-KIR: Statistics for Release 2.9.0 (December 2019). EMBL-EBI Immuno Polymorphism Database.

- 36.Held W, Kunz B. An allele-specific, stochastic gene expression process controls the expression of multiple Ly49family genes and generates a diverse, MHC-specific NK cell receptor repertoire. European journal of immunology. 1998;28(8):2407–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yawata M, Yawata N, Draghi M, Partheniou F, Little A-M, Parham P. MHC class I–specific inhibitory receptors and their ligands structure diverse human NK-cell repertoires toward a balance of missing self-response. Blood. 2008;112(6):2369–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fauriat C, Ivarsson MA, Ljunggren HG, Malmberg KJ, Michaelsson J. Education of human natural killer cells by activating killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors. Blood. 2010;115(6):1166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johansson S, Johansson M, Rosmaraki E, Vahlne G, Mehr R, Salmon-Divon M, et al. Natural killer cell education in mice with single or multiple major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201(7):1145–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saleh A, Davies GE, Pascal V, Wright PW, Hodge DL, Cho EH, et al. Identification of probabilistic transcriptional switches in the Ly49 gene cluster: A eukaryotic mechanism for selective gene activation. Immunity. 2004;21(1):55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boudreau JE, Giglio F, Gooley TA, Stevenson PA, Le Luduec J-B, Shaffer BC, et al. KIR3DL1/HLA-B Subtypes Govern Acute Myelogenous Leukemia Relapse After Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(20):2268–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boudreau JE, Mulrooney TJ. KIR3DL1 and HLA-B Density and Binding Calibrate NK Education and Response to HIV. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2016;196(8):3398–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu J, Venstrom JM, Liu XR, Pring J, Hasan RS, O’Reilly RJ, et al. Breaking tolerance to self, circulating natural killer cells expressing inhibitory KIR for non-self HLA exhibit effector function after T cell-depleted allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113(16):3875–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brodin P, Kärre K, Höglund P. NK cell education: not an on-off switch but a tunable rheostat. Trends in Immunology. 2009;30(4):143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Capanni M, Urbani E, Carotti A, Aloisi T, et al. Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood. 2007;110(1):433–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, Tosti A, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science (New York, NY). 2002;295(5562):2097–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russo A, Oliveira G, Berglund S, Greco R, Gambacorta V, Cieri N, et al. NK cell recovery after haploidentical HSCT with posttransplant cyclophosphamide: dynamics and clinical implications. Blood. 2018;131(2):247–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willemze R, Rodrigues CA, Labopin M, Sanz G, Michel G, Socié G, et al. KIR-ligand incompatibility in the graft-versus-host direction improves outcomes after umbilical cord blood transplantation for acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rocha V, Ruggeri A, Spellman S, Wang T, Sobecks R, Locatelli F, et al. Killer Cell Immunoglobulin-Like Receptor-Ligand Matching and Outcomes after Unrelated Cord Blood Transplantation in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22(7):1284–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka J, Morishima Y, Takahashi Y, Yabe T, Oba K, Takahashi S, et al. Effects of KIR ligand incompatibility on clinical outcomes of umbilical cord blood transplantation without ATG for acute leukemia in complete remission. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3(11):e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brunstein CG, Wagner JE, Weisdorf DJ, Cooley S, Noreen H, Barker JN, et al. Negative effect of KIR alloreactivity in recipients of umbilical cord blood transplant depends on transplantation conditioning intensity. Blood. 2009;113(22):5628–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Health Resources & Services Adminstration Transplant Activity Report; https://bloodstemcell.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bloodstemcell/data/transplant-activity/transplants-disease-donor.pdf; Accessed July 8th 2020.

- 53.Dehn J, Spellman S, Hurley CK, Shaw BE, Barker JN, Burns LJ, et al. Selection of unrelated donors and cord blood units for hematopoietic cell transplantation: guidelines from the NMDP/CIBMTR. Blood. 2019;134(12):924–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gragert L, Eapen M, Williams E, Freeman J, Spellman S, Baitty R, et al. HLA Match Likelihoods for Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Grafts in the U.S. Registry. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(4):339–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller JS, Cooley S, Parham P, Farag SS, Verneris MR, McQueen KL, et al. Missing KIR ligands are associated with less relapse and increased graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following unrelated donor allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2007;109(11):5058–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsu KC, Gooley T, Malkki M, Pinto-Agnello C, Dupont B, Bignon JD, et al. KIR ligands and prediction of relapse after unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12(8):828–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsu KC, Keever-Taylor CA, Wilton A, Pinto C, Heller G, Arkun K, et al. Improved outcome in HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia predicted by KIR and HLA genotypes. Blood. 2005;105(12):4878–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsu KC, Liu X-R, Selvakumar A, Mickelson E, O’Reilly RJ, Dupont B. Killer Ig-Like Receptor Haplotype Analysis by Gene Content: Evidence for Genomic Diversity with a Minimum of Six Basic Framework Haplotypes, Each with Multiple Subsets. The Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(9):5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weisdorf D, Cooley S, Wang T, Trachtenberg E, Vierra-Green C, Spellman S, et al. KIR B donors improve the outcome for AML patients given reduced intensity conditioning and unrelated donor transplantation. Blood Advances. 2020;4(4):740–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cooley S, Weisdorf DJ, Guethlein LA, Klein JP, Wang T, Le CT, et al. Donor selection for natural killer cell receptor genes leads to superior survival after unrelated transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2010;116(14):2411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cooley S, Trachtenberg E, Bergemann TL, Saeteurn K, Klein J, Le CT, et al. Donors with group B KIR haplotypes improve relapse-free survival after unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2009;113(3):726–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooley S, Weisdorf DJ, Guethlein LA, Klein JP, Wang T, Marsh SGE, et al. Donor Killer Cell Ig-like Receptor B Haplotypes, Recipient HLA-C1, and HLA-C Mismatch Enhance the Clinical Benefit of Unrelated Transplantation for Acute Myelogenous Leukemia. The Journal of Immunology. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weisdorf D, Cooley S, Wang T, Trachtenberg E, Haagenson MD, Vierra-Green C, et al. KIR Donor Selection: Feasibility in Identifying better Donors. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2019;25(1):e28–e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tarek N, Gallagher MM, Chou JF, Lubin MN, Heller G, Barker JN, et al. KIR and HLA genotypes have no identifiable role in single-unit dominance following double-unit umbilical cord blood transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015;50(1):150–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sekine T, Marin D, Cao K, Li L, Mehta P, Shaim H, et al. Specific combinations of donor and recipient KIR-HLA genotypes predict for large differences in outcome after cord blood transplantation. Blood. 2016;128(2):297–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cognet C, Farnarier C, Gauthier L, Frassati C, André P, Magérus-Chatinet A, et al. Expression of the HLA-C2-specific activating killer-cell Ig-like receptor KIR2DS1 on NK and T cells. Clinical Immunology. 2010;135(1):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Le Luduec J-B, Boudreau JE, Freiberg JC, Hsu KC. Novel Approach to Cell Surface Discrimination Between KIR2DL1 Subtypes and KIR2DS1 Identifies Hierarchies in NK Repertoire, Education, and Tolerance. 2019;10(734). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chewning JH, Gudme CN, Hsu KC, Selvakumar A, Dupont B. KIR2DS1-positive NK cells mediate alloresponse against the C2 HLA-KIR ligand group in vitro. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2007;179(2):854–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Venstrom JM, Pittari G, Gooley TA, Chewning JH, Spellman S, Haagenson M, et al. HLA-C-dependent prevention of leukemia relapse by donor activating KIR2DS1. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(9):805–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pittari G, Liu XR, Selvakumar A, Zhao Z, Merino E, Huse M, et al. NK cell tolerance of self-specific activating receptor KIR2DS1 in individuals with cognate HLA-C2 ligand. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2013;190(9):4650–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Venstrom JM, Gooley TA, Spellman S, Pring J, Malkki M, Dupont B, et al. Donor activating KIR3DS1 is associated with decreased acute GVHD in unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115(15):3162–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garcia-Beltran WF, Hölzemer A, Martrus G, Chung AW, Pacheco Y, Simoneau CR, et al. Open conformers of HLA-F are high-affinity ligands of the activating NK-cell receptor KIR3DS1. Nature immunology. 2016;17(9):1067–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yawata M, Yawata N, Draghi M, Little A, Partheniou F, Parham P. Roles for HLA and KIR polymorphisms in natural killer cell repertoire selection and modulation of effector function. J Exp Med. 2006;203:633–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.O’Connor G, Guinan K, Cunningham R, Middleton D, Parham P, Gardiner C. Functional polymorphism of the KIR3DL1/S1 receptor on human NK cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carr W, Pando M, Parham P. KIR3DL1 polymorphisms that affect NK cell inhibition by HLA-Bw4 ligand. J Immunol. 2005;175:5222–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yawata M, Yawata N, Draghi M, Partheniou F, Little A, Parham P. MHC class I-specific inhibitory receptors and their ligands structure diverse human NK cell repertoires towards a balance of missing-self response. Blood. 2008;112:2369–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gardiner C, Guethlein L, Shilling H, Pando M, Carr W, Rajalingam R, et al. Different NK cell surface phenotypes defined by the DX9 antibody are due to KIR3DL1 gene polymorphism. J Immunol. 2001;166:2992–3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schetelig J, Baldauf H, Heidenreich F, Massalski C, Frank S, Sauter J, et al. External Validation of Models for KIR2DS1/KIR3DL1-informed Selection of Hematopoietic Cell Donors fails. Blood. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van der Ploeg K, Le Luduec J-B, Stevenson PA, Park S, Gooley TA, Petersdorf EW, et al. HLA-A alleles influencing NK cell function impact AML relapse following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood Advances. (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang X, Feng J, Chen S, Yang H, Dong Z. Synergized regulation of NK cell education by NKG2A and specific Ly49 family members. Nature Communications. 2019;10(1):5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kamiya T, Seow SV, Wong D, Robinson M, Campana D. Blocking expression of inhibitory receptor NKG2A overcomes tumor resistance to NK cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2019;129(5):2094–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Horowitz A, Djaoud Z, Nemat-Gorgani N, Blokhuis J, Hilton HG, Béziat V, et al. Class I HLA haplotypes form two schools that educate NK cells in different ways. Sci Immunol. 2016;1(3):eaag1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hosseini E, Schwarer AP, Ghasemzadeh M. Do human leukocyte antigen E polymorphisms influence graft-versus-leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation? Experimental hematology. 2015;43(3):149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tsamadou C, Fürst D, Wang T, He N, Lee SJ, Spellman SR, et al. Donor HLA-E Status Associates with Disease-Free Survival and Transplant-Related Mortality after Non In Vivo T Cell-Depleted HSCT for Acute Leukemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2019;25(12):2357–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hosseini E, Schwarer AP, Jalali A, Ghasemzadeh M. The impact of HLA-E polymorphisms on relapse following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia research. 2013;37(5):516–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kollman C, Spellman SR, Zhang M-J, Hassebroek A, Anasetti C, Antin JH, et al. The effect of donor characteristics on survival after unrelated donor transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2016;127(2):260–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saber W, Opie S, Rizzo JD, Zhang MJ, Horowitz MM, Schriber J. Outcomes after matched unrelated donor versus identical sibling hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults with acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(17):3908–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu E, Tong Y, Dotti G, Shaim H, Savoldo B, Mukherjee M, et al. Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity. Leukemia. 2018;32(2):520–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu E, Marin D, Banerjee P, Macapinlac HA, Thompson P, Basar R, et al. Use of CAR-Transduced Natural Killer Cells in CD19-Positive Lymphoid Tumors. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382(6):545–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ciurea SO, Schafer JR, Bassett R, Denman CJ, Cao K, Willis D, et al. Phase 1 clinical trial using mbIL21 ex vivo-expanded donor-derived NK cells after haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2017;130(16):1857–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee DA, Denman CJ, Rondon G, Woodworth G, Chen J, Fisher T, et al. Haploidentical Natural Killer Cells Infused before Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation for Myeloid Malignancies: A Phase I Trial. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22(7):1290–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bachanova V, Cooley S, Defor TE, Verneris MR, Zhang B, McKenna DH, et al. Clearance of acute myeloid leukemia by haploidentical natural killer cells is improved using IL-2 diphtheria toxin fusion protein. Blood. 2014;123(25):3855–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Casucci M, Volpi I, Tosti A, Perruccio K, et al. Role of natural killer cell alloreactivity in HLA-mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1999;94(1):333–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Verneris MR, Miller JS, Hsu KC, Wang T, Sees JA, Paczesny S, et al. Investigation of donor KIR content and matching in children undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute leukemia. Blood Adv. 2020;4(7):1350–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]