Abstract

The understaffing of nursery schools and kindergartens and the increasing workload of childcare workers are becoming significant issues in Japan. In this study, a cross-sectional survey was conducted to investigate the stress experienced by childcare workers and its antecedents. We distributed 2,640 questionnaires to childcare workers in Miyagi prefecture, obtaining a response rate of 51.9% (n=1,370). Finally, 1,210 valid questionnaires were used in the analysis. As a stress indicator, psychological distress was measured with the Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (K6). The mean K6 score was 7.0 (SD=5.4), and the prevalence of psychological distress (K6 score ≥5) was 60.0%. Considering work-related factors, the mean scores were as follows: supervisor support 11.8 (2.6), coworker support 12.1 (2.0), work engagement 3.2 (1.2), and effort-reward ratio 0.93 (0.53). A multivariate logistic regression analysis with adjustment for possible confounders revealed that increased psychological distress was associated with higher effort-reward ratio, lower support from supervisors and coworkers, lower work engagement, and insufficient sleep. These results suggest that elevated psychological distress is strongly associated with effort-reward imbalance, while high work engagement in childcare workers helped to reduce their distress.

Keywords: Psychological distress, Childcare workers, Effort-reward imbalance, Work engagement, Supervisor support, Coworker support

Introduction

The utilization rate of nursery schools and kindergartens is increasing1) due to the rising employment rate of women and the increase in dual-income households2). As the number of children on nursery school waiting lists has become an issue, the national and local governments in Japan have implemented several policies such as “Acceleration Plan for Eliminating All Waiting Lists for Childcare Openings” and “Plan for Raising Children in a Peaceful Environment” to address this problem3). One of the causes of these waiting lists is a lack of workforce in nursery schools and kindergartens. The turnover rate of nursery school and kindergarten teachers (hereinafter referred to as “childcare workers”) is higher than that of other occupational group, and many individuals do not work as childcare workers even though they are qualified to do so4). In recent years, specialized knowledge and skills are required for childcare, as the number of children needing extra support due to developmental problems has been increasing and communication difficulties with dissatisfied parents have emerged. Furthermore, the government commenced the plan for free preschool education in October 20195); therefore, the utilization rate of childcare facilities will rise, and the burden of childcare workers will increase even more. Considering all of the above, the physical and mental health of childcare workers is of concern.

The mechanism underlying occupational ill health has been illustrated by various previous work-stress models6,7,8,9). Of these, the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) model is appropriate for describing the stressful work environment of childcare workers. It also predicts health conditions for a wide range of working populations based on two axes, namely “effort” and “reward” in occupational life9, 10), and a strong association with psychological distress has been indicated11, 12). Conversely, it has also been reported that worksite social support from supervisors and coworkers and work engagement can relieve work-related stress13,14,15,16).

Surveys on work-related stress have been conducted targeting various occupations11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21), although most have focused on nurses and health workers. Similarly, surveys on stress response and burnout have been conducted with childcare workers22,23,24,25). However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been few surveys based on the ERI model targeting childcare workers. In Japan, where the childcare situation has been undergoing major fluctuations, it is urgent to evaluate the stress of childcare workers and to examine the factors that cause it.

We therefore conducted a cross-sectional study in Miyagi prefecture, Northeast Japan, to investigate psychological distress and the factors that cause it among childcare workers based on the ERI model. As an indicator of stress, we used psychological distress measured by the Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (K6). We expect that the results of this study will provide basic data for the future development of workplaces where childcare workers can work comfortably.

Methods

Participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted with childcare workers and managers employed at public or private nursery schools, kindergartens, and certified kodomo-en (a type of combination of nursery school and kindergarten) in Miyagi prefecture from July to December 2018. There are approximately 680 of these childcare facilities in the study area26, 27). An ordinance-designated city and two relatively well populated outlying cities were set as the survey area with approval from the cities’ governments, and 165 childcare facilities in the area were set as the surveyed facilities with approval from the facilities’ managers.

We distributed self-administered anonymous questionnaires at each childcare facility, and the facility manager distributed them to individual childcare workers. In total, 2,640 questionnaires were distributed, and 1,370 responses were collected by mail (response rate=51.9%). Of these, 160 questionnaires had missing data on the study variables (psychological distress, gender, age, marital status, having a preschool child, educational status, smoking habit, drinking habit, exercise habit, sleep hours per day, type of employment, job title, overtime work, supervisor support, coworker support, work engagement, and effort-reward [ER] ratio) and were thus excluded from the analyses. Because there were many questionnaires in which the household income value (n=150) and type of childcare facility (n=11) were not provided, the category “unknown” was set, and these variables were included in the analysis. Finally, 1,210 responses from childcare workers and managers were analyzed in this study.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the Shokei Gakuin University (Approval number: 017-022) and Wakayama Medical University (Approval number: 2308). The study participants were fully informed of the study purpose and answered the questionnaire anonymously; their participation was completely voluntary and the responses were mailed directly to the researchers.

Measures

Psychological distress was measured using the Japanese version of the K628, 29), which consists of six items addressing how frequently respondents have experienced symptoms of psychological distress during the past 30 d. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time), with total scores ranging 0–24. Higher scores indicate more severe mental distress, and a score of 5 or more was used as the cut-off for determining psychological distress30). The internal reliability was found to be sufficiently high in the current study with a Cronbach’s α of 0.897.

We also collected gender, age, marital status, having a preschool child, educational status, and household income as sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables. Additionally, smoking habit (Yes=currently smoking), drinking habit (Yes=drinking more than twice a month), exercise habit (Yes=exercising for more than 30 min two or more times a week and for more than a year), and sleep hours per day were collected as lifestyle variables. Type of childcare facility, type of employment, job title, overtime work (Yes=working more than 8 h per day), supervisor support, coworker support, work engagement, and ER ratio were collected as work-related variables.

Worksite social support from supervisors and coworkers was measured separately using a subscale of the Job Content Questionnaire7, 31). Each of the four items assuming support from supervisors and coworkers were rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (I disagree completely) to 4 (I agree completely). The internal reliability of the supervisor support and coworker support subscales was high in the current study, with Cronbach’s α being 0.921 and 0.839, respectively.

Work engagement was measured using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale32, 33), which assesses how frequently respondents experience engagement (dedication, vigor, and absorption) in their work. The items are rated from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). The total score for this scale was calculated by averaging the item scores. The internal reliability was high in the current study (Cronbach’s α=0.938).

ER ratio was measured using a subscale of the ERI Questionnaire9, 34). Six items for job effort and 11 items for job reward were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (I feel no distress at all) to 5 (I feel very distressed). The ER ratio was calculated to evaluate the balance between job effort and job reward, and was computed as the total effort score divided by the total reward score, adjusted for the unequal numbers of items included in the two total scores. A ratio of 1 indicates ER balance, whereas a ratio of >1 indicates a critical level of ERI. The internal reliability of the job effort and job reward scales was high in the current study (Cronbach’s α=0.899 and α=0.885, respectively).

Statistical analysis

The differences in characteristics of the participants between those who experienced psychological distress (K6 score ≥5) and those who did not were analyzed with the χ2 test. Associations between psychological distress and each factor were analyzed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression, with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the factors that showed significant differences in the χ2 test (age group, marital status, household income, sleep hours per day, job title, overtime work, supervisor support, coworker support, work engagement, and ER ratio) and gender were used as possible confounders. Spearman’s rank-correlation coefficients between these confounders were used to check for multicollinearity. The significance level for all statistical analyses was set at p<0.05 (two-tailed). All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP software package version 14.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

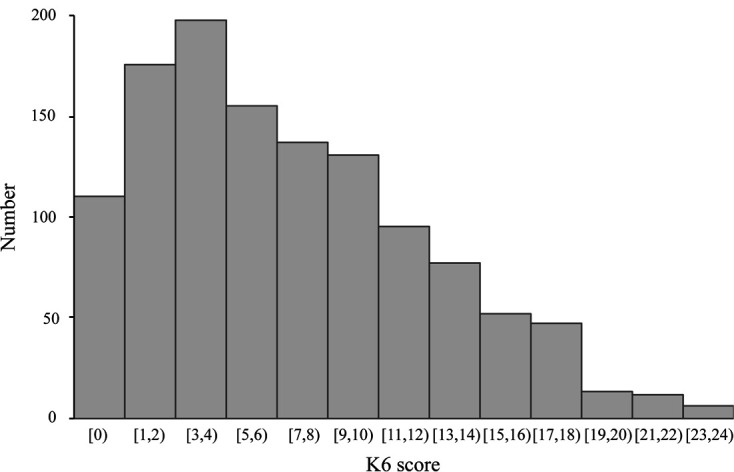

The distribution of the K6 scores is shown in Fig. 1. The mean overall K6 score was 7.0 (SD=5.4), and the prevalence of psychological distress (K6 score ≥5) was 60.0%. Regarding work-related factors, the overall mean scores were as follows: supervisor support 11.8 (2.6), coworker support 12.1 (2.0), and work engagement 3.2 (1.2). As for ERI factor, the mean score of effort was 19.6 (6.1), and that of reward was 42.7 (8.9); thus, the mean ER ratio was 0.93 (0.53). The prevalence of ERI (ER ratio >1) was 36.7%.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the total score of the Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (K6) for the participants (n=1,210).

The mean score was 7.0 (SD=5.4), and the prevalence of psychological distress (K6 score ≥5) was 60.0%.

Table 1 shows the results of the characteristics of participants analyzed according to the presence or absence of psychological distress. The participants with psychological distress—compared with those without it—tended to be younger, be single, divorced, or widowed, have a lower household income, get insufficient sleep, be non-managers, work overtime, receive lower support from supervisors and coworkers, have lower work engagement, and have higher ER ratio.

Table 1. . Comparisons of characteristics between respondents with and without psychological distress (K6 score ≥5).

| <5 (n=484) | ≥5 (n=726) | χ2 | p* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 23 | 4.8 | 32 | 4.4 | 0.08 | 0.778 |

| Female | 461 | 95.2 | 694 | 95.6 | ||

| Age group (yr) | ||||||

| <30 | 134 | 27.7 | 236 | 32.5 | 8.21 | 0.042 |

| 30−39 | 112 | 23.1 | 182 | 25.1 | ||

| 40−49 | 98 | 20.2 | 148 | 20.4 | ||

| ≥50 | 140 | 28.9 | 160 | 22.0 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 296 | 61.2 | 343 | 47.2 | 22.55 | <0.001 |

| Single, divorced, or widowed | 188 | 38.8 | 383 | 52.8 | ||

| Having a preschool child | ||||||

| Yes | 90 | 18.6 | 106 | 14.6 | 3.41 | 0.065 |

| No | 394 | 81.4 | 620 | 85.4 | ||

| Educational status (yr) | ||||||

| <16 | 361 | 74.6 | 538 | 74.1 | 0.04 | 0.851 |

| ≥16 | 123 | 25.4 | 188 | 25.9 | ||

| Household income (Japanese Yen/yr) | ||||||

| <5 million | 178 | 36.8 | 358 | 49.3 | 20.84 | <0.001 |

| 5−10 million | 197 | 40.7 | 222 | 30.6 | ||

| ≥10 million | 49 | 10.1 | 56 | 7.7 | ||

| Unknown | 60 | 12.4 | 90 | 12.4 | ||

| Lifestyle factors | ||||||

| Smoking habit | ||||||

| Yes | 21 | 4.3 | 40 | 5.5 | 0.83 | 0.362 |

| No | 463 | 95.7 | 686 | 94.5 | ||

| Drinking habit | ||||||

| Yes | 232 | 47.9 | 318 | 43.8 | 2 | 0.157 |

| No | 252 | 52.1 | 408 | 56.2 | ||

| Exercise habit | ||||||

| Yes | 114 | 23.6 | 154 | 21.2 | 0.92 | 0.337 |

| No | 370 | 76.4 | 572 | 78.8 | ||

| Sleep hours per day | ||||||

| ≥6 | 322 | 66.5 | 390 | 53.7 | 19.68 | <0.001 |

| <6 | 162 | 33.5 | 336 | 46.3 | ||

| Work-related factors | ||||||

| Type of childcare facility | ||||||

| Nursery school | 365 | 75.4 | 570 | 78.5 | 2.25 | 0.522 |

| Kindergarten | 69 | 14.3 | 90 | 12.4 | ||

| Certified kodomo-en | 44 | 9.1 | 61 | 8.4 | ||

| Unknown | 6 | 1.2 | 5 | 0.7 | ||

| Type of employment | ||||||

| Regular employment | 370 | 76.4 | 570 | 78.5 | 0.715 | 0.398 |

| Non-regular employment | 114 | 23.6 | 156 | 21.5 | ||

| Job title | ||||||

| Managerial position | 45 | 9.3 | 34 | 4.7 | 10.13 | 0.002 |

| Non-managerial position | 439 | 90.7 | 692 | 95.3 | ||

| Overtime work | ||||||

| Yes | 155 | 32 | 298 | 41 | 10.09 | 0.002 |

| No | 329 | 68 | 428 | 59 | ||

| Supervisor support (JCQ) | ||||||

| ≥Median | 388 | 80.2 | 421 | 58 | 64.45 | <0.001 |

| <Median | 96 | 19.8 | 305 | 42 | ||

| Coworker support (JCQ) | ||||||

| ≥Median | 398 | 82.2 | 456 | 62.8 | 52.75 | <0.001 |

| <Median | 86 | 17.8 | 270 | 37.2 | ||

| Work engagement (UWES) | ||||||

| ≥Median | 320 | 66.1 | 331 | 45.6 | 49.21 | <0.001 |

| <Median | 164 | 33.9 | 395 | 54.4 | ||

| Effort-reward ratio (ERIQ) | ||||||

| ≤1 | 405 | 83.7 | 361 | 49.7 | 144.12 | <0.001 |

| >1 | 79 | 16.3 | 365 | 50.3 | ||

JCQ: Job Content Questionnaire; UWES: Utrecht Work Engagement Scale; ERIQ: Effort-Reward Imbalance Model Questionnaire.

*The differences were tested by χ2 test.

The factors associated with psychological distress are shown in Table 2. In the univariable logistic regression analysis, psychological distress was significantly associated with the age groups <30 and 30–39, being single, divorced, or widowed, having a household income of less than 5 million Japanese Yen/year, getting less than 6 h of sleep per day, having a non-managerial position, working overtime, having lower levels of support from supervisors and coworkers, having lower work engagement, and having higher ER ratio.

Table 2. Association between psychological distress (K6 score ≥5) and relative factors (n=1,210).

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p* | OR (95% CI) | p† | |

| Sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors | ||||

| Age group (yr) | ||||

| <30 | 1.54 (1.13−2.10) | 0.006 | 1.04 (0.68−1.60) | 0.848 |

| 30−39 | 1.42 (1.03−1.97) | 0.035 | 0.98 (0.66−1.45) | 0.922 |

| 40−49 | 1.32 (0.94−1.86) | 0.11 | 0.99 (0.67−1.46) | 0.962 |

| ≥50 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Single, divorced, or widowed | 1.76 (1.39−2.22) | <0.001 | 1.37 (0.99−1.89) | 0.056 |

| Household income (Japanese Yen/yr) | ||||

| <5 million | 1.76 (1.15−2.69) | 0.009 | 1.18 (0.72−1.93) | 0.518 |

| 5−10 million | 0.99 (0.64−1.51) | 0.949 | 0.76 (0.47−1.21) | 0.248 |

| ≥10 million | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Unknown | 1.31 (0.79−2.17) | 0.29 | 0.86 (0.49−1.52) | 0.604 |

| Lifestyle factors | ||||

| Sleep hours per day | ||||

| ≥6 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| <6 | 1.71 (1.35−2.17) | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.12−1.92) | 0.005 |

| Work-related factors | ||||

| Job title | ||||

| Managerial position | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Non-managerial position | 2.09 (1.32−3.31) | 0.002 | 1.18 (0.69−2.02) | 0.535 |

| Overtime work | ||||

| Yes | 1.48 (1.16−1.88) | 0.002 | 1.03 (0.78−1.37) | 0.826 |

| No | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Supervisor support (JCQ) | ||||

| ≥Median | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| <Median | 2.93 (2.24−3.83) | <0.001 | 1.54 (1.13−2.11) | 0.006 |

| Coworker support (JCQ) | ||||

| ≥Median | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| <Median | 2.74 (2.08−3.62) | <0.001 | 1.72 (1.25−2.36) | <0.001 |

| Work engagement (UWES) | ||||

| ≥Median | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| <Median | 2.33 (1.83−2.95) | <0.001 | 1.53 (1.16−2.00) | 0.002 |

| Effort-reward ratio (ERIQ) | ||||

| ≤1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| >1 | 5.18 (3.91−6.87) | <0.001 | 3.55 (2.60−4.85) | <0.001 |

JCQ: Job Content Questionnaire; UWES: Utrecht Work Engagement Scale; ERIQ: Effort-Reward Imbalance Model Questionnaire.

*The differences were tested by univariate logistic regression analysis.

†The differences were tested by multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for gender, age group, marital status, household income, sleep hours per day, job title, overtime work, supervisor support, coworker support, work engagement, and effort-reward ratio.

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted by the variables with significant associations in Table 1 (age group, marital status, household income, sleep hours per day, job title, overtime work, supervisor support, coworker support, work engagement, and ER ratio) and gender, psychological distress was significantly associated with less than 6 h of sleep per day, lower support from supervisors and coworkers, lower work engagement, and higher ER ratio. Particularly, there was a strong association between ER ratio and psychological distress. The maximum Spearman’s rank-correlation coefficient was observed to be 0.515 between age and marital status; thus, it was considered that there was no evidence of multicollinearity in this model.

Discussion

This study examined psychological distress and its related factors among childcare workers. Psychological distress (K6 score ≥5) was found in 60.0% of the study participants and was significantly and independently associated with ER ratio, coworker support, supervisor support, work engagement, and sleep hours per day. Specifically, ER ratio was strongly associated with psychological distress. As mentioned earlier, there have been few surveys on work-related stress based on the ERI model targeting childcare workers. Therefore, the findings from this study could provide valuable information for improving the working conditions of childcare workers.

The mean K6 score was similar or higher than that reported by previous surveys with 789 Japanese nurses (7.7 [5.3])16) and 348 female nurses (6.2 [5.4])17). Regarding other occupations, the K6 score was 5.6 (4.6) among 60 female Japanese employees in the manufacturing industry20) and 5.2 (5.1) among 2,191 Japanese local government employees21). It has been stated that nurses have lower mental health compared with the general population or employees of general companies, which might be due to the heavy physical and psychological burden that is often caused by accidents and failures while performing their duties35, 36). Because the mean K6 score in this study was almost the same as that of nurses in existing studies, the results of the current study indicate that childcare workers may also be an occupational group with high psychological distress.

The mean scores for worksite social support from supervisors and coworkers were significantly and independently associated with psychological distress. These mean scores were higher than those reported in a previous survey with 3,078 female employees at nine companies in Japan (10.5 [2.4] for supervisor support, 11.0 [1.7] for coworker support)37). Uemura and Nanakida38) stated that mentoring relationships between managers and childcare workers as well as seniors and juniors were easily formed because each childcare facility operates according to its own childcare policy. These occupational characteristics are considered to be a reason why worksite social support can be easily obtained among childcare workers.

The mean work engagement scores reported for other occupations was 2.2 (1.0) among 306 female Japanese nurses15) and 2.4 (1.0) among 60 female Japanese employees in the manufacturing industry20), and the score of childcare workers was higher than these. Workers with high work engagement feel that their work is rewarding and work diligently, and work engagement can be considered a condition for experiencing vitality at work14). Childcare workers can show their expertise and are appreciated by both children and families39). These feelings of reward may be the reason why the work engagement of childcare workers was the highest compared with other occupations.

The mean ER ratio among childcare workers in the current study was 0.93, which is higher than in other occupations: 0.8 (0.4) for 348 nurses17), 0.5 (0.4) for 1,000 female office employees40), and 0.7 (0.3) for 2,208 female specialists40). It has been reported that childcare workers are dissatisfied with their working environment concerning elements such as working hours, paid vacations, salary, and employee benefits39). Dissatisfaction with insufficient compensation for long working hours and heavy workload might be the reason for the higher ER ratio among childcare workers compared with other occupations.

Previous surveys have reported that ERI and psychological distress are related11, 12), and this study shows similar results. An excessive labor load, weight of responsibility, and disproportionate salary levels seem to be cited as the causes of the ERI among childcare workers. Although we could not assess personal income level of the participants because the questionnaire did not include an item for individual annual income, the salaries of childcare workers have been reported to be lower than in other occupations41). The Japan Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare has been promoting the improvement of salaries for childcare workers42); however, an increase in monetary reward is difficult to implement immediately. Increasing psychosocial rewards, however, would be possible and effective as an immediate approach to resolving ERI. From the results of this study, receiving psychosocial rewards might be adequate for childcare workers, as work engagement and worksite social support from supervisors and coworkers were higher than those of nurses or other occupational groups. Further studies are needed to clarify other psychosocial rewards required for childcare workers.

This study had the following limitations. First, because of its cross-sectional design, causal associations could not be confirmed; a longitudinal study will be required to investigate potential causal relationships. Second, a self-assessment method was used; all variables were measured only by subjective indicators based on questionnaires. In future studies, objective indicators—such as physiological or biochemical indicators—will be needed for the evaluation of stress. Third, the response rate in our study was somewhat low at 51.9%, which may have led to selection bias. Fourth, as this study was only conducted in the Tohoku area, there might be regional characteristics. For example, the effect of the Great East Japan Earthquake should be considered. Therefore, caution must be used when generalizing the results. Fifth, the K6 score showed a wide distribution (Fig. 1), and it is expected that the factors related to stress would differ depending on the cut-off used; thus, it will be necessary to explore other cut-off points in a future study.

In conclusion, despite the limitations mentioned above, this study indicated that childcare workers are an occupational group with high stress, even though their work engagement is high. Additionally, ERI was most strongly associated with psychological distress.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant numbers: JP 17K12873 and 17H04137). The funding sources had no role in the study protocol; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the study for publication. The authors thank all participants in this study.

References

- 1.Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2019) A report on the status related to day-care center, etc. (Apr. 1, 2019) and the results of the survey on “Plan for raising children in a peaceful environment”. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11907000/000544879.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 2.Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan (2018) White paper on gender equality 2018. http://www.gender.go.jp/about_danjo/whitepaper/h30/gaiyou/pdf/h30_gaiyou.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 3.Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2014) For achievement of the zero children waiting list. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/children/children-childrearing/dl/150407–03.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 4.Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2015) Related materials of nursery teachers, etc. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-11901000-Koyoukintoujidoukateikyoku-Soumuka/s.1_3.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 5.Cabinet Office, Government of Japan (2019) Learn about free early childhood education and care. https://www.youhomushouka.go.jp/about/en/. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 6.Cooper CL, Marshall J. (1976) Occupational sources of stress: a review of the literature relating to coronary heart disease and mental ill health. J Occup Psychol 49, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karasek RA. (1979) Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurrell JJ, Jr., McLaney MA. (1988) Exposure to job stress—a new psychometric instrument. Scand J Work Environ Health 14Suppl 1, 27–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegrist J. (1996) Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol 1, 27–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsutsumi A, Kawakami N. (2004) A review of empirical studies on the model of effort-reward imbalance at work: reducing occupational stress by implementing a new theory. Soc Sci Med 59, 2335–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki K, Sasaki H, Motohashi Y. (2010) Relationships among mood/anxiety disorder, occupational stress and the life situation: results of survey of a local government staff. Health Sci Bull Akita Univ 18, 120–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nohara M, Tatsuta H, Kitano N, Hoshino H, Kamo T, Tai T, Tamaki T, Nanjo H. (2013) Correlations between mood/anxiety disorders and working environment, occupational stress, health-related QOL, and fatigue among working women. Jpn J Occup Med Traumat 61, 360–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komatsu Y, Kai Y, Nagamatsu T, Shiwa T, Suyama Y, Sugimoto M. (2010) [Buffering effect of social support in the workplace on job strain and depressive symptoms]. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 52, 140–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimazu A. (2010) Job stress and work engagement. Stress Sci Res 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kagata S, Inoue A, Kubota K, Shimazu A. (2015) Association of emotional labor with work engagement and stress responses among hospital ward nurses. J Behav Med 21, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunie K, Kawakami N, Shimazu A, Yonekura Y, Miyamoto Y. (2017) The relationship between work engagement and psychological distress of hospital nurses and the perceived communication behaviors of their nurse managers: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 71, 115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kikuchi Y, Nakaya M, Ikeda M, Okuzumi S, Takeda M, Nishi M. (2014) Relationship between depressive state, job stress, and sense of coherence among female nurses. Indian J Occup Environ Med 18, 32–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uchiyama A, Odagiri Y, Ohya Y, Suzuki A, Hirohata K, Kosugi S, Shimomitsu T. (2011) Association of social skills with psychological distress among female nurses in Japan. Ind Health 49, 677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayasaka Y, Nakamura K, Yamamoto M, Sasaki S. (2007) Work environment and mental health status assessed by the general health questionnaire in female Japanese doctors. Ind Health 45, 781–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuno K, Kawakami N, Inoue A, Ishizaki M, Tabata M, Tsuchiya M, Akiyama M, Kitazume A, Kuroda M, Shimazu A. (2009) Intragroup and intergroup conflict at work, psychological distress, and work engagement in a sample of employees in Japan. Ind Health 47, 640–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuno K, Kawakami N, Shimazu A, Shimada K, Inoue A, Leiter MP. (2017) Workplace incivility in Japan: reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the modified Work Incivility Scale. J Occup Health 59, 237–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishimoto N, Fuji K. (2020) Influence of casual conversation in nursery schools on nursery teachers’ stress reactions. Jpn J Psychol 91, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikeda Y, Okawa I. (2012) The relation between day nursery and preschool teachers’ thoughts about job stressors and their mental state regarding work: work duties and work environment as mediating factors. Jpn J Dev Psychol 23, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura N, Akagawa Y. (2016) Research on childcare worker stress: focus on relationship between causes of stress in the workplace and causes of individual stress. Res Bull Naruto Univ Educ 31, 136–45. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumura T. (2015) Review of stressors experienced by pre-school teachers. J Osaka Univ Compr Child Educ 10, 203–13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2017) Survey of social welfare institution in 2017. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/fukushi/17/index.html. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 27.Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (2019) School basic survey in 2019. https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/toukei/chousa01/kihon/kekka/k_detail/1419591_00001.htm. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 28.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32, 959–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, Tachimori H, Iwata N, Uda H, Nakane H, Watanabe M, Naganuma Y, Hata Y, Kobayashi M, Miyake Y, Takeshima T, Kikkawa T. (2008) The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 17, 152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakurai K, Nishi A, Kondo K, Yanagida K, Kawakami N. (2011) Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 65, 434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawakami N, Kobayashi F, Araki S, Haratani T, Furui H. (1995) Assessment of job stress dimensions based on the job demands- control model of employees of telecommunication and electric power companies in Japan: reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Job Content Questionnaire. Int J Behav Med 2, 358–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M. (2006) The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross-national study. Educ Psychol Meas 66, 701–16. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimazu A, Schaufeli WB, Kosugi S, Suzuki A, Nashiwa H, Kato A, Sakamoto M, Irimajiri H, Amano S, Hirohata K, Goto R, Kitaoka-Higashiguchi K. (2008) Work engagement in Japan: validation of the Japanese version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Appl Psychol 57, 510–23. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsutsumi A, Ishitake T, Peter R, Siegrist J, Matoba T. (2001) The Japanese version of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire: a study in dental technicians. Work Stress 15, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakai M, Oda Y, Takahashi Y, Tabuchi Y, Kimura N, Morioka I. (2011) Relationship between work-life balance and mental health of nurses in a hospital. Jpn J Health Educ Prom 19, 302–12. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mori T, Kageyama T. (1995) [A cross-sectional survey on mental health and working environment of hospital nurses]. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 37, 135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawakami N, Haratani T, Kobayashi F, Ishizaki M, Hayashi T, Fujita O, Aizawa Y, Miyazaki S, Hiro H, Masumoto T, Hashimoto S, Araki S. (2004) Occupational class and exposure to job stressors among employed men and women in Japan. J Epidemiol 14, 204–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uemura M, Nanakida A. (2008) Empirical research on the structure of social support in child care givers’. J Child Health 67, 854–60. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Japan National Council of Social Welfare (2008) Survey report on recruitment and development of human resources in social welfare facilities. https://www.keieikyo.com/data/jinzai3.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 40.Tsutumi A .(2007) Website of the Japanese version of effort-reward imbalance questionnaire. https://mental.m.u-tokyo.ac.jp/jstress/ERI/manual.htm. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 41.Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2017) The average wage of nursery teachers. https://jsite.mhlw.go.jp/miyagi-roudoukyoku/var/rev0/0119/7609/ho3.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 42.Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2017) Regarding construct a mechanism of career development and improve working condition in nursery teachers. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-11900000-Koyoukintoujidoukateikyoku/0000155997.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020.