Abstract

BACKGROUND

Solid organ transplant recipients are considered to be at high-risk of developing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related complications. The optimal treatment for this patient group is unknown. Consequently, the treatment of COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients should be determined individually, considering patient age and comorbidities, as well as graft function, time of transplant, and immunosuppressive treatment. Immunosuppressive treatments may give rise to severe COVID-19. On the contrary, they may also lead to a milder and atypical presentation by diminishing the immune system overdrive.

CASE SUMMARY

A 50-year old female kidney transplant recipient presented to the transplant clinic with a progressive dry cough and fever that started three days ago. Although the COVID-19 test was found to be negative, chest computed tomography images showed consolidation typical of the disease; thus, following hospital admission, anti-bacterial and COVID-19 treatments were initiated. However, despite clinical improvement of the lung consolidation, her creatinine levels continued to increase. Ultrasound of the graft showed no pathology. The tacrolimus blood level was determined and the elevation in creatinine was found to be related to an interaction between tacrolimus and azithromycin.

CONCLUSION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, various single or combination drugs have been utilized to find an effective treatment regimen. This has increased the possibility of drug interactions. A limited number of studies published in the literature have highlighted some of these pharmacokinetic interactions. Treatments used for COVID-19 therapy; azithromycin, atazanavir, lopinavir/ritonavir, remdesivir, favipiravir, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, nitazoxanide, ribavirin, and tocilizumab, interact with immunosuppressive treatments, most importantly with calcineurin inhibitors. Thus, their levels should be frequently monitored to prevent toxicity.

Keywords: COVID-19, Kidney transplantation, Drug interaction, Pharmacokinetics, Azithromycin, Case report, Calcineurin inhibitor

Core Tip: This case report is illustrative for dilemmas experienced by transplant professionals while managing kidney transplant recipients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). By reporting this case, we intend to create awareness of drug interactions observed in renal transplant recipients with COVID-19.

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplant recipients are considered a high-risk group for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related complications due to the vulnerability constituted by immunosuppressive treatments. The duration after transplant and graft function are the most crucial factors for the management of kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19[1]. A kidney transplant recipient`s risk of developing COVID-related complications should be evaluated individually considering immunosuppressive treatment and comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and atherosclerotic disease)[2].

On the other hand, immunosuppressive therapy may have positive effects on the disease course in kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19 by decreasing the viral load. Several studies have demonstrated that COVID-19 viral replication depended on active immunophilin pathways. The immunosuppressive drugs tacrolimus and cyclosporine arrested coronavirus proliferation in human cells and inhibited their replication through these pathways[3,4].

In addition to classic clinical symptoms of COVID-19, renal transplant recipients may present with atypical symptoms, such as diarrhea and vomiting. This atypical presentation with a negative COVID-19 test may lower the suspicion of infection in an otherwise infected individual. Therefore, in the case of controversy, unenhanced chest scans with a low dose of IV contrast should be obtained to ensure patient safety and reduce complications.

This study demonstrates the lessons learned while managing a kidney transplant recipient infected with COVID-19 and the pharmacokinetic interactions encountered related to its treatment.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 50-year old female kidney transplant recipient presented to the transplant clinic with a progressive dry cough and fever that started three days ago.

History of present illness

She described accidentally being in contact with a symptomatic COVID-19 positive individual 7 d prior to her cough and fever.

History of past illness

She had received a standard criteria deceased donor kidney seven years ago with anti-thymocyte globulin induction. Since then her kidney function was stable with maintenance immunosuppressants consisting of tacrolimus (1.5 mg/d), mycophenolate mofetil (720 mg/d), and prednisone (5 mg/d).

Personal and family history

She did not smoke, consume alcohol, or have coronary artery disease. Her only comorbidity was mild hypertension treated with amlodipine (10 mg/d). Her family history was unremarkable.

Physical examination

On examination, her temperature was 38 °C, heart rate 100 bpm, respiratory rate 14 breaths/min, blood pressure 120/60 mmHg, and oxygen saturation 96%. Auscultation of the chest revealed bilateral fine crackles at the base of the lungs.

Laboratory examinations

Her graft function was stable with a minimum elevation from her baseline creatinine of 0.9 to 1.1 mg/dL. The glomerular filtration rate was 58.5 mL/min. Complete blood count showed increased white blood cells (20800/μL) with a total lymphocyte count of 1210/μL. The hemoglobin and platelet counts were 10.6 g/dL and 177.000/μL, respectively. The remaining biochemical parameters were within normal ranges. A high level of C-reactive protein (CRP) was noted (276 mg/L). Complete urine analysis was unremarkable. Lastly, her trough tacrolimus level was 5.5 ng/mL.

Imaging examinations

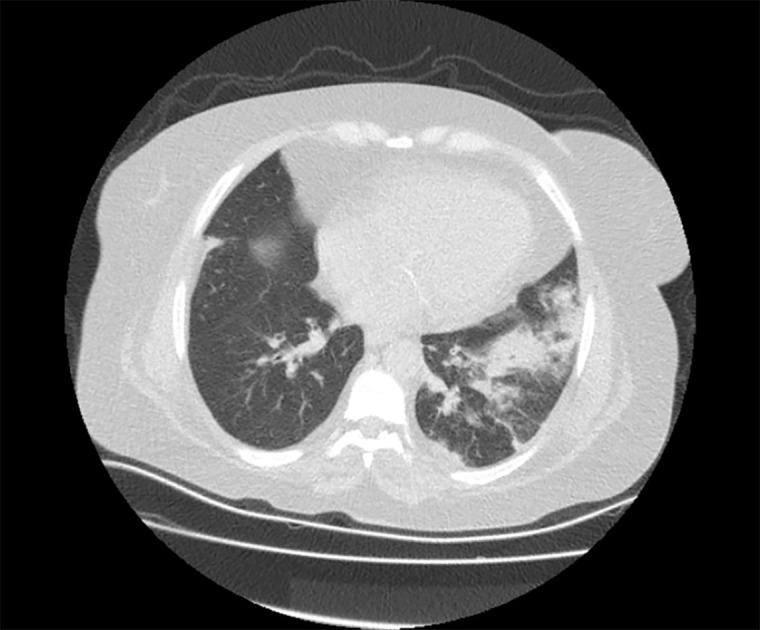

Chest X-ray was normal. Although the patient did not give a history of traveling abroad or contacting COVID-19 positive individuals, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained. The scan revealed consolidation areas with air bronchograms in the left lower lobe with pneumonic infiltrations (Figure 1). A nasopharyngeal swab to test for COVID-19, influenza A/B was obtained. Additionally, blood samples for cytomegalovirus (CMV) and BK virus serology were sent to the microbiology department to diagnose opportunistic viral infections.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan of the chest, which showed consolidation areas with air bronchogram in the left lung lower lobe, and pneumonic infiltration. Coronavirus disease 2019 was not eliminated.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

With an infectious disease specialist`s recommendations and considering the chest CT images showing consolidation typical of the disease, anti-bacterial and COVID-19 treatments were initiated. This empirical treatment consisted of piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5 g three times a day), azithromycin (500 mg load, then 250 mg/d), chloroquine (800 mg/d load, then 400 mg/d), and oseltamivir (75 mg/d). No modification of the existing maintenance immunosuppressive treatment was considered at this time (antiproliferative, calcineurin inhibitor, steroid).

TREATMENT

Upon admission to hospital, intravenous hydration was initiated to support oral hydration and maintain daily urinary output. On the second day of admission creatinine continued to rise to 1.2 mg/dL. Ultrasound of the abdomen and transplant revealed no pathology. The COVID-19, influenza, CMV, and BK virus results were negative. Oseltamivir treatment was ceased and although the COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was negative, chloroquine 400 mg/d and azithromycin 250 mg/d were continued due to the suspicious findings on chest CT and the patient’s risk group. To treat possible bacterial pneumonia, piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5 g three times a day) administration was continued for a further ten days.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The creatinine level continued to increase on the 6th post-admission day up to 1.4 mg/dL. One the same day tacrolimus trough level was found to be 23.58 ng/mL (Table 1). The elevation in creatinine was considered to be due to high tacrolimus blood levels. The medication list was reviewed by the transplant nephrology team for possible drug interactions. Macrolide antibiotics were thought to be the cause of this elevation. As the patient had no fever since admission and both blood cell count and CRP levels had returned to normal ranges, the macrolide antibiotic azithromycin was stopped. Subsequently, the serum tacrolimus level decreased to within the therapeutıc range (5.9 ng/mL), and creatinine levels returned to baseline. The patient was discharged on the 7th postadmission day, a follow-up appointment at the outpatient clinic one week later showed excellent graft function.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings on admission and follow-up of the patient

|

|

Admission

|

PA-day 2

|

PA-day 4

|

PA-day 6

|

PA-day 8

|

PA-day 10

|

Clinic

|

| Urea (mg/dL) | 45 | 49 | 53 | 59 | 50 | 42 | 40 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI) (mL/min/1.73 m²) | 58.5 | 52.7 | 47.8 | 43.7 | 52.7 | 58.5 | 76.4 |

| Tacrolimus level (ng/mL) | 5.5 | 7 | - | 23.58 | 12 | 6.3 | 5.9 |

eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; PA: Post admission.

DISCUSSION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing COVID-19, which was first identified in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019, has become a worldwide pandemic. Contact history, clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings should be combined for an accurate diagnosis. Most patients with COVID-19 do not have severe respiratory problems and present with mild, flu-like symptoms. The most common symptoms recorded included fever, dry cough, myalgia, and tiredness. Among the diagnostic tests PCR, as well as, lymphopenia and bilateral ground-glass opacification on CT scan were found to be highly beneficial in the diagnosis of COVID-19[6,7].

On the other hand, COVID-19 may have a variety of presentations in renal transplant recipients. The few cases reported in the literature provide low-quality scientific evidence[1,2,8-10]. There is a lack of evidence-based effective antiviral treatment for COVID-19. While experimental pharmacological therapy with limited scientific evidence can be wise in addition to a risk-benefit calculation, pharmaceutical interactions should always be kept in mind.

Patients of any age with a medical diagnosis of cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, heart failure, and type 2 diabetes fall into the risk group for COVID-related complications. Additionally, elderly patients over 65 years of age are associated with higher intensive care unit (ICU) admission rates when infected with COVID-19. The 50-year-old patient described in this report only had the risk factor of receiving immunosuppressive treatment.

Patients with clinical suspicion and positive thoracic CT findings or PCR test results considered to have COVID are treated as per the recommendations of the Turkish Ministry of Health COVID treatment guidelines. The patient described in this report had unilateral pneumonic infiltration without ground glass opacification on the CT scan. Although the PCR test result was negative, COVID-19 treatment was initiated due to the CT findings and the patient's status. As our patient was not critically ill, no modification of the immunosuppressive regimen was required.

Literature reports show the impact of uncontrolled inflammation and cytokine storm syndrome on COVID-19 related mortality[11]. As a result, new treatment methods are focused on diminishing uncontrolled inflammation and preventing excessive cytokine release such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha. Maintenance immunosuppressive treatments may have a positive impact on disease progression by reducing viral replication, suppressing the cytokine storm, and preventing immune activation[12]. On the other hand, patients with COVID-19 presenting with critical illness constitute a different dilemma. As critical illness due to COVID-19 is a life-threatening multisystem condition that can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in renal transplant recipients, immunosuppressive therapies should be modified to avoid serious complications. These modifications should be evaluated individually as one case is not the same as another. Briefly, a targeted immunosuppression regimen should be preferred.

The targeted immunosuppression regimen should include a low-dose corticosteroid (CS) due to its anti-inflammatory effects and immunomodulatory characteristics. Additionally, inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines by steroids maintains the integrity of vascular endothelium and regulates endothelial permeability. Thus, it is common to increase the CS dose while decreasing or stopping the other immuno-suppressive treatments. Antiproliferative immunosuppressant agents should be ceased during COVID-19 therapy. It is not clear whether calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) doses should be reduced or not. CNI withdrawal is recommended for patients with severe pneumonia that may need intubation[8].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, various single or combination drugs have been used in the search for an effective treatment. The search underscores the significance of drug interactions. QT monitoring is mandatory when hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin are combined[13]. QT prolongation, mostly seen in pharmaceutical interactions, was not detected in our patient. A limited number of studies have emphasized the significance of pharmaceutical interactions between immuno-suppressive treatments and COVID-19 therapy[14]. Medications used for COVID-19 therapy, including, azithromycin, atazanavir, lopinavir/ritonavir, remdesivir, favipiravir, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, nitazoxanide, ribavirin, and tocilizumab may interact with immunosuppressive treatments through different pathways. Mycophenolate potentially interacts with lopinavir/ritonavir. A dose reduction and close laboratory monitoring are required when both drugs are used in combination. Sirolimus is known to increase the level of atazanavir and lopinavir/ritonavir; therefore, their combination is contradictory. Calcineurin inhibitors increase the serum levels of atazanavir, lopinavir/ritonavir, chloroquine, and hydroxychloroquine. Dose adaptation and close monitoring are recommended. Finally, CNI may slightly decrease tocilizumab levels[15]. Macrolides increase CNI levels through their interaction with the p450 enzyme. The macrolide azithromycin is well known for its minimal effect on the p450 enzyme system[16].

Our patient demonstrated elevated tacrolimus drug levels and a subsequent increase in serum creatinine, as a result of the addition of azithromycin to treat COVID-19. After the withdrawal of azithromycin, tacrolimus levels rapidly returned to target values. Target CNI values for renal transplant patients with COVID-19 should be between 4 and 6 ng/mL. As azithromycin may interact with CNI, CNI blood levels should be checked frequently when both are combined.

CONCLUSION

Kidney transplant patients are at risk of COVID-19 depending on the time of transplant, graft function, age, and comorbidities. Immunosuppression may lead to severe COVID-19 with complications. However, a decrease in viral load due to immunosuppressive treatment may lead to a milder and atypical presentation.

A reduction in immunosuppressive treatment should be considered in critically ill patients. In addition, special attention should be paid to the pharmaceutical interactions between antibiotics, antivirals, and immunosuppressants. Modification of immunosuppressive therapy in COVID-19 patients entails cessation of antiproliferative therapy. In addition to this, an increase rather than a reduction in steroid dose is necessary. Calcineurin inhibitor withdrawal may be required depending on the presentation and progression of COVID-19. If there is no need to withdraw CNI treatment, then, serum trough levels should be frequently monitored to prevent graft toxicity.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from the patient and a scanned copy has been provided with the submission documents.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Turkish Society of Gastroenterology, Health Sciences University.

Peer-review started: July 26, 2020

First decision: October 21, 2020

Article in press: November 5, 2020

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country/Territory of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Hilmi I, Sureshkumar K S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Li X

Contributor Information

Ebru Gok Oguz, Department of Nephrology, Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Res Hosp, Ankara 6500, Turkey.

Kadir Gokhan Atilgan, Department of Nephrology, Health Sciences University, Ankara 6500, Turkey.

Sanem Guler Cimen, Department of General Surgery, Diskapi Research and Training Hospital, Health Sciences University, Ankara 65000, Select One, Turkey. s.cimen@dal.ca.

Hatice Sahin, Department of Nephrology, Health Sciences University, Ankara 6500, Turkey.

Tamer Selen, Department of Nephrology, Health Sciences University, Ankara 6500, Turkey.

Fatma Ayerden Ebinc, Department of Nephrology, Health Sciences University, Ankara 6500, Turkey.

Sertac Cimen, Department of Urology and Transplantation, Health Sciences University, Ankara 65000, Select One, Turkey.

Mehmet Deniz Ayli, Department of Nephrology and Transplantation, Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Teaching and Research Hospital, Ankara 6500, Turkey.

References

- 1.Zhu L, Xu X, Ma K, Yang J, Guan H, Chen S, Chen Z, Chen G. Successful recovery of COVID-19 pneumonia in a renal transplant recipient with long-term immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1859–1863. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang H, Chen Y, Yuan Q, Xia QX, Zeng XP, Peng JT, Liu J, Xiao XY, Jiang GS, Xiao HY, Xie LB, Chen J, Liu JL, Xiao X, Su H, Zhang C, Zhang XP, Yang H, Li H, Wang ZD. Identification of Kidney Transplant Recipients with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Eur Urol. 2020;77:742–747. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carbajo-Lozoya J, Müller MA, Kallies S, Thiel V, Drosten C, von Brunn A. Replication of human coronaviruses SARS-CoV, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E is inhibited by the drug FK506. Virus Res. 2012;165:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfefferle S, Schöpf J, Kögl M, Friedel CC, Müller MA, Carbajo-Lozoya J, Stellberger T, von Dall'Armi E, Herzog P, Kallies S, Niemeyer D, Ditt V, Kuri T, Züst R, Pumpor K, Hilgenfeld R, Schwarz F, Zimmer R, Steffen I, Weber F, Thiel V, Herrler G, Thiel HJ, Schwegmann-Wessels C, Pöhlmann S, Haas J, Drosten C, von Brunn A. The SARS-coronavirus-host interactome: identification of cyclophilins as target for pan-coronavirus inhibitors. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002331. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willicombe M, Thomas D, McAdoo S. COVID-19 and Calcineurin Inhibitors: Should They Get Left Out in the Storm? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1145–1146. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, Tan YY, Chen SD, Jin HJ, Tan KS, Wang DY, Yan Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillen E, Pineiro GJ, Revuelta I, Rodriguez D, Bodro M, Moreno A, Campistol JM, Diekmann F, Ventura-Aguiar P. Case report of COVID-19 in a kidney transplant recipient: Does immunosuppression alter the clinical presentation? Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1875–1878. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gandolfini I, Delsante M, Fiaccadori E, Zaza G, Manenti L, Degli Antoni A, Peruzzi L, Riella LV, Cravedi P, Maggiore U. COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1941–1943. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang J, Lin H, Wu Y, Fang Y, Kumar R, Chen G, Lin S. COVID-19 in posttransplant patients-report of 2 cases. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1879–1881. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmadpoor P, Rostaing L. Why the immune system fails to mount an adaptive immune response to a COVID-19 infection. Transpl Int. 2020;33:824–825. doi: 10.1111/tri.13611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bessière F, Roccia H, Delinière A, Charrière R, Chevalier P, Argaud L, Cour M. Assessment of QT Intervals in a Case Series of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection Treated With Hydroxychloroquine Alone or in Combination With Azithromycin in an Intensive Care Unit. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1067–1069. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartiromo M, Borchi B, Botta A, Bagalà A, Lugli G, Tilli M, Cavallo A, Xhaferi B, Cutruzzulà R, Vaglio A, Bresci S, Larti A, Bartoloni A, Cirami C. Threatening drug-drug interaction in a kidney transplant patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Transpl Infect Dis. 2020;22:e13286. doi: 10.1111/tid.13286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liverpool Drug Interaction Group. COVID-19 Drug Interactions. Available from: http://www.covid19-druginteractions.org .

- 16.Jeong R, Quinn RR, Lentine KL, Lloyd A, Ravani P, Hemmelgarn B, Braam B, Garg AX, Wen K, Wong-Chan A, Gourishankar S, Lam NN. Outcomes Following Macrolide Use in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2019;6:2054358119830706. doi: 10.1177/2054358119830706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]