Abstract

Context

The work-life interface has been a much discussed and researched area within athletic training. The National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement on work-life balance highlighted the profession's interest in this topic. However, gaps in the literature remain and include the roles of time-based conflict and social support.

Objective

To compare work-family conflict (WFC) and social support among athletic trainers (ATs) employed in the 2 most common practice settings.

Design

Cross-sectional observational survey.

Setting

Collegiate and secondary school settings.

Patients or Other Participants

A total of 474 (females = 231, males = 243) ATs who were employed in the collegiate (205, 43.2%) or secondary school (269, 56.8%) setting.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Data were collected through a Web-based survey designed to measure conflict and social support. Likert responses were summed. Demographic information was analyzed for frequency and distribution. Independent t tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were calculated to determine group differences. Linear regression was used to determine if social support predicted WFC.

Results

Social provisions and WFC were negatively correlated, and the social provisions score predicted WFC. No WFC differences (P = .778) were found between collegiate and high school ATs even though collegiate ATs worked more hours (63 ± 11) during their busiest seasons compared with those in the high school setting (54 ± 13, P < .001). Similarly, no difference (P = .969) was present between men and women, although men worked more hours. Our participants scored highest on time-based WFC items.

Conclusions

Work-family conflict was experienced globally in 2 of the most common athletic training settings and between sexes. This indicates WFC is universally experienced and therefore needs to be addressed, specifically with a focus on time-based conflict. In addition to time-management strategies, ATs need support from coworkers, peers, and family members.

Keywords: social support, work-life balance, work-family balance, retention

Key Points

No difference in experiences with work-family conflict (WFC) were noted between male and female athletic trainers who were parents.

Time-based WFC superseded other facets of WFC conflict (strain and behavior based).

Experiences with WFC did not differ between collegiate and secondary school athletic trainers.

Concerns regarding an athletic trainer's (AT's) ability to find work-life balance have been documented in the literature1–3 and have been of particular interest due to the link between work-life balance and lower levels of job satisfaction and experiences of burnout,4 both precursors to departure from the field.4,5 Although this topic has been studied extensively in the athletic training literature, the perspective of the AT parent is still limited.6 In 2 settings, collegiate and secondary school, AT parents face the demands of long, atypical working hours often combined with the stress of required travel and schedule changes.

Work-family conflict (WFC) and work-family balance are terms used in the literature to describe a paradigm that involves the effects work, family, and life roles can have on one another. Conflict simply implies that work, family, and life roles do not exist in harmony, whereas balance insinuates that they can in fact be congruent.7 Work-family conflict, particularly among those individuals who are balancing full-time jobs, marriage, and children, can lead to burnout and dissatisfaction.4 The intersection of these factors has become an area of interest8–12 for researchers, as it appears that imbalance of and conflict between these roles (ie, parenthood, working professional) can lead to departure from one's job. Previous researchers6 indicated that women displayed increased guilt with respect to WFC and that both male and female ATs believed their current employment settings did not support their parental role. Women found that balancing work and family was stressful and caused burnout, whereas men expressed difficulty in creating balance as a working parent.6

Conceptualizing the factors leading to departure from one's given field is multidimensional, and this framework includes organizational, personal, and sociocultural components.8–11 Organizational factors are grounded in time, specifically working hours (ie, long workweeks, inflexible schedules, nights, weekends).1,2 Most attention in the literature has been given to the job demands and organizational climate in which ATs worked and their effects on the working and home lives of these individuals.1–5

Personal and sociocultural factors include family values, personality, support system, gender, and societal norms as they relate to work and family.12,13 Sociocultural-level factors include norms and values linked with work and family. Due to prevailing societally driven gender norms, women typically have a more difficult time maintaining both work and family responsibilities, and they reported that they must constantly prove their worthiness.13 Balancing parenthood and work was difficult for ATs,14 and often ATs, particularly women, found that family obligations and spending time with family were neglected.

In some cases, gender can mediate the experiences of WFC. Women who are trying to balance it all may experience conflicts because they want to be successful in both roles.15 Female ATs described themselves as adaptive15 and may experience conflict between work and home when they feel that they lack enough time or energy to engage in those roles.14,15 Although growing evidence suggests that WFC in athletic training is not related to gender,16,17 female ATs have historically demonstrated concerns regarding the time commitment related to the role and the effects it can have on motherhood.2,14

Colleges and secondary schools are the most common employment settings for ATs18 and have been studied for ATs' experiences of WFC.2,4,19 However, to our knowledge, the settings have yet to be explored in the same sample. It appears that the time spent at work is a major facilitator of WFC for ATs in both settings, as they work in excess of 40 hours per week. Thus, understanding WFC within these settings is important.18

The National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) position statement on facilitating work-life balance,3 as well as recent literature,17,20 highlighted the significance of social support for ATs as they pursue a more balanced lifestyle. Social support is an important aspect of a person's quality of life and is provided by multiple sources, including a spouse, family, and friends. Social support occurs in various forms, sources, and types. Forms of social support can include both behavior and perceptions, whereas sources may include individuals from either one's work (coworker, supervisor) or personal (spouse, friends, family members) life. Types of social support include emotional, appraisal, informational, and instrumental methods. Emotional support involves resources such as trust, care, and love. Appraisal support alters a person's assessment of strain. Informational support describes information or advice that is given to prevent strain. Instrumental support offers tangible resources (eg, time, money) to help cope with strain.21 For the AT, social support can come from coworkers and supervisors who promote teamwork and job sharing in the workplace,3 as well as from spouses and family members who can absorb domestic and parenting duties when the AT's workload is high. To our knowledge, no authors have examined WFC and social support in the same sample, particularly among those who are parents. Additionally, whether social support can mitigate WFC among ATs who are parents in the collegiate or secondary school setting is unclear. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to quantitatively examine WFC and social support among collegiate and high school ATs who were parents.

Our research was guided by the following hypotheses:

H1:

Athletic trainers working in the collegiate setting would experience more WFC than ATs working in the secondary school setting.

H2:

Athletic trainers would experience greater time-based conflict than strain and behaviorally based conflict.

H3:

Female ATs would experience greater amounts of WFC than male ATs.

H4:

Athletic trainers with social support would experience less WFC.

METHODS

Research Design

We used a cross-sectional design to assess WFC and social support among ATs employed in the collegiate or secondary school setting. Participants responded to a Web-based survey housed on the Qualtrics platform (Provo, UT). This study was approved by the University of Conneticut Institution Review Board before data collection.

Participants

We recruited ATs who were employed in the collegiate or secondary school setting and practicing clinically (at least 50% of their job description involved patient care) and had at least 1 child. The email addresses for the secondary school ATs were obtained using the Korey Stringer Institute and NATA's Athletic Training Location and Services (ATLAS) Project database, which is maintained by the institute at the University of Connecticut. Athletic trainers who completed the ATLAS survey within the previous year were contacted. The email addresses for collegiate ATs were obtained through our professional networks as well as online searches of collegiate athletic training staffs across the United States. Recruitment emails were sent to 1474 collegiate ATs and 2219 secondary school ATs. Initially, 879 ATs responded (348 college, 531 secondary school; 24% response rate), but after screening for those who did not complete at least 90% of the survey, did not currently work in either setting, did not practice clinically for 50% of the time, or did not have children, a total of 474 responses (205 college, 269 secondary school) were eligible for analysis (13% response rate).

Instrumentation

Demographic questions on age, sex, number of children, and marital status were included in our survey so that we could group participants when reporting data. Additional information collected was NATA district membership, years of certification by the Board of Certification, and average hours worked per week. We used 2 previously validated scales to measure WFC and social support.

The WFC Scale is an 18-item scale designed to measure various facets of conflict, including time, strain, and behavior-based conflict.22 These 3 dimensions of conflict are bidirectional in that work may interfere with family, and family may interfere with work. Time-based conflict may occur when the time required for 1 role interferes with participation in another role. For example, this can occur when providing athletic training services at an event and thereby missing a child's sporting event or needing to attend a family event and being unable to provide morning treatments in the athletic training room. Strain-based conflict describes the strain experienced in 1 role and its effect on another role. In this case, strain at work from relationships with coworkers and coaches may interfere with relationships at home with family members or vice versa. Behavior-based conflict exists when the behaviors necessary for 1 role are not compatible with those of another role. In an administrative role, a high level of authority and aggressiveness is often necessary, but this type of demeanor may be inappropriate in some home situations. Similarly, the AT parent of a young child who requires more nurturing behaviors may experience challenges if the AT's job involves working with an older population. The 18-item scale has been shown to be reliable and valid22 and was also reliable in our sample (α = .89). It has not previously been used in the athletic training literature. Responses are on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of WFC.

The Social Provisions Scale23 was used to evaluate the ATs' current relationships with friends, family, coworkers, and others and quantify their social support. The 24-item scale was reliable and valid in a prior study23 and was also reliable and valid in our sample (α = .91). The scale assesses 6 social provisions: guidance, reassurance of worth, social integration, attachment, nurturance, and reliable alliance. Using a 4-point Likert scale, participants evaluated their current relationships (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree); a higher score indicated the individual received more social support.

Data-Collection Procedures

Volunteers were asked to indicate if they worked in the collegiate or secondary school setting, spent at least 50% of their time providing patient care, and were parents. If all 3 answers were affirmative, they were asked a series of demographic questions and then 42 questions related to WFC and social support. Follow-up reminders were sent at 1 and 4 weeks after the initial email.

Statistical Analyses

The a priori level was set at P < .05. All data were downloaded into an Excel (version 16.38; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet and cleaned. Responses were removed if less than 90% of the survey was completed or if the qualifying questions were not answered. The dataset was input into SPSS (version 25; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) for analysis.

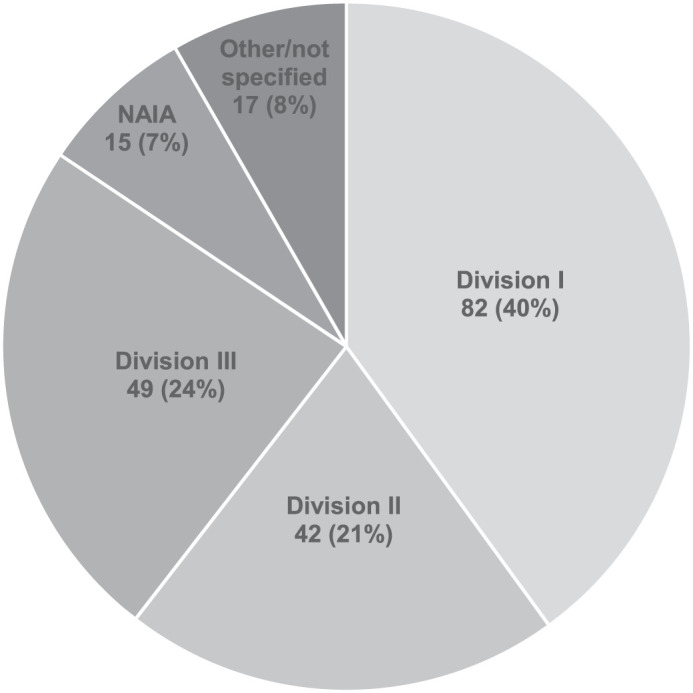

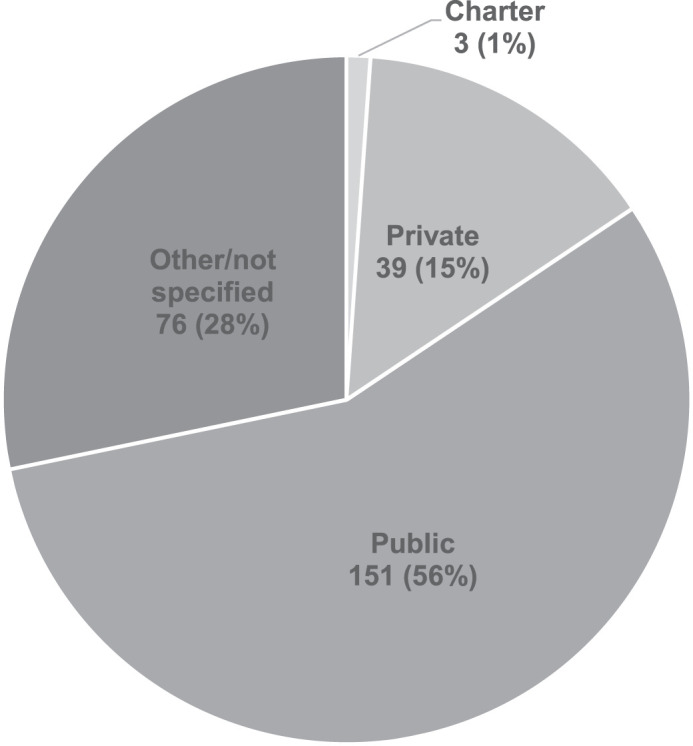

Total scores were calculated for both the WFC and Social Provisions Scales. Frequencies were calculated by setting, sex, NATA district, and marital status (Table 1). Descriptive data were calculated for age, number of children, years of certification by the Board of Certification, hours worked, WFC Scale total, and Social Provisions Scale total (Figures 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Athletic Trainers' Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic |

Athletic Trainers |

|

| College or University |

Secondary School |

|

| Total participants | 205 | 269 |

| Age, mean ± SD (range), y | 42 ± 9 (25–65) | 42 ± 9 (24–68) |

| Sex, No. | ||

| Female | 102 | 129 |

| Male | 103 | 140 |

| Marital status, No. | ||

| Cohabiting | 3 | 6 |

| Divorced | 9 | 7 |

| Married | 186 | 250 |

| Separated | 4 | 1 |

| Single | 1 | 5 |

| Widowed | 2 | 0 |

| Children, mean ± SD (range) | 2 ± 1 (1–5) | 2 ± 1 (1–7) |

| Certified by Board of Certification, mean ± SD (range), y | 18 ± 9 (2–43) | 17 ± 9 (0–42) |

Figure 1.

Collegiate or university setting breakdown. Divisions refer to the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Abbreviation: NAIA, National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics.

Figure 2.

Secondary school setting breakdown.

We conducted Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests to examine the normality of variables. Data for the WFC Scale were normally distributed, whereas data for the Social Provisions Scale were nonnormally distributed. Independent t tests were used to determine if differences existed in WFC scores between the collegiate and secondary school ATs and between men and women. Because the data were nonparametric, Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to identify differences between collegiate and secondary school ATs and between women and men for the social provisions scale. Similarly, Mann-Whitney U tests were also used to examine if any differences were present in the number of hours worked by college and secondary school ATs and women and men. A Spearman correlation was generated to determine the relationship between WFC and social provisions. We conducted a linear regression with WFC score as the dependent variable and the Social Provisions score as the independent variable to investigate if the latter predicted the former. The Cronbach α was calculated to determine reliability in our population for both scale scores.

RESULTS

Respondents

A total of 474 (women = 231, men = 243) ATs completed the Web-based survey. Participants were from the collegiate or university setting (205, 43.2%) or the secondary school (269, 56.8%) setting as categorized by the NATA. Respondents reported working 56 ± 13 hours during their busy seasons (ie, in-seasons), and 35 ± 11 during their nonbusy season (out of season or summer). All 10 NATA districts were represented. Participants were 41 ± 9 years old and credentialed as ATs for 18 ± 9 years. Most ATs were married (n = 436, 92%), and all had children (mean = 2 ± 1, range = 1–7).

Sources of WFC

Of the 3 aspects of conflict addressed in the WFC Scale (time, strain, behavior based), time-based conflict appeared to be the greatest antecedent to WFC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Work-Family Conflict Itemsa

| Scale Questions |

Mean ± SD |

| Time-based work interference with family | |

| 1: My work keeps me from my family activities more than I would like. | 4.0 ± 0.90 |

| 2: The time I must devote to my job keeps me from participating equally in household responsibilities and activities. | 3.6 ± 1.2 |

| 3: I have to miss family activities due to the amount of time I must spend on work responsibilities. | 4.0 ± 0.94 |

| Time-based family interference with work | |

| 4: The time I spend on family responsibilities often interferes with my work responsibilities. | 2.3 ± 1.0 |

| 5: The time I spend with my family often causes me not to spend time in activities at work that could be helpful to my career. | 2.3 ± 1.1 |

| 6: I have to miss work activities due to the amount of time I must spend on family responsibilities. | 1.9 ± 0.93 |

| Strain-based work interference with family | |

| 7: When I get home from work I am often too frazzled to participate in family activities or responsibilities. | 2.7 ± 1.1 |

| 8: I am often so emotionally drained when I get home from work that it prevents me from contributing to my family. | 2.7 ± 1.2 |

| 9: Due to all the pressures at work, sometimes when I come home, I am too stressed to do the things I enjoy. | 3.0 ± 1.2 |

| Strain-based family interference with work | |

| 10: Due to stress at home, I am often preoccupied with family matters at work. | 2.2 ± 1.0 |

| 11: Because I am often stressed from family responsibilities, I have a hard time concentrating on my work. | 2.0 ± 0.96 |

| 12: Tension and anxiety from my family life often weakens my ability to do my job. | 1.8 ± 0.90 |

| Behavior-based work interference with family | |

| 13: The problem-solving behaviors I use in my job are not effective in resolving problems at home. | 2.4 ± 1.1 |

| 14: Behavior that is effective and necessary for me at work would be counterproductive at home. | 2.5 ± 1.1 |

| 15: The behaviors I perform that make me effective at work do not help me to be a better parent and spouse. | 2.4 ± 1.1 |

| Behavior-based family interference with work | |

| 16: The behaviors that work for me at home do not seem to be effective at work. | 2.4 ± 1.1 |

| 17: Behavior that is effective and necessary for me at home would be counterproductive at work. | 2.3 ± 1.0 |

| 18: The problem-solving behaviors that work for me at home does not seem to be as useful at work. | 2.4 ± 1.0 |

Work-Family Conflict 18-item scale (Carlson et al 200023); 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Instrument is presented in its original format.

Our first hypothesis was not supported, as the WFC scores of ATs in collegiate (49.3 ± 11) and secondary school (45.0 ± 10.8, t472 = 4.204; P = .778) settings did not differ.

Our second hypothesis was supported: participants had higher scores on the time-based scale items than on the strain and behavior-based conflict items (Table 2).

Our third hypothesis was unsupported, as no WFC difference was present between women (46.8 ± 10.9) and men (46.9 ± 11.1; t472 = 0.039, P = .969).

Our fourth hypothesis was confirmed, as WFC and social provisions were moderately negatively correlated (r = −0.496, P < .001).

Hours Worked

During their busiest seasons, collegiate ATs worked more hours (63 ± 11) than secondary school ATs (54 ± 13; U = 16 691; P < .001). During their least busy time of year, no differences were present (collegiate ATs = 35 ± 10 hours, secondary school ATs = 35 ± 12 hours; U = 28 971; P = .239).

Men worked more hours (61 ± 13) than women (55 ± 12) during their busiest time of year (U = 35 320, P < .001). Men also worked more hours (37 ± 12) during their least busy time of the year as compared with women (33 ± 10; U = 33 638; P < .001).

Linear Regression

The Social Provisions Scale score predicted the WFC Scale score (b = −0.483, t473 = −11.979; P < .001). A significant regression equation was found (F1,472 = 143.485; P < .001), with R2 = 0.233. Participants' predicted total WFC score was equal to 94.430−0.566 (social provisions total score). The Social Provisions Scale items, as well as the mean and standard deviation for each item in our population, are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Social Provisions Scale Itemsa

| Scale Question |

Mean ± SD |

| 1: There are people I can depend on to help me if I really need it. | 3.5 ± 0.76 |

| 2: I feel that I do not have close personal relationships with other people.b | 3.1 ± 0.93 |

| 3: There is no one I can turn to for guidance in times of stress.b | 3.4 ± 0.77 |

| 4: There are people who depend on me for help. | 3.8 ± 0.51 |

| 5: There are people who enjoy the same social activities I do. | 3.3 ± 0.71 |

| 6: Other people do not view me as competent.b | 3.6 ± 0.66 |

| 7: I feel personally responsible for the wellbeing of another person. | 3.8 ± 0.51 |

| 8: I feel part of a group of people who share my attitudes and beliefs. | 3.2 ± 0.73 |

| 9: I do not think other people respect my skills and abilities.b | 3.2 ± 0.83 |

| 10: If something went wrong, no one would come to my assistance.b | 3.6 ± 0.70 |

| 11: I have close relationships that provide me with a sense of emotional security and wellbeing. | 3.3 ± 0.75 |

| 12: There is someone I could talk to about important decisions in my life. | 3.6 ± 0.63 |

| 13: I have relationships where my competence and skill are recognized. | 3.4 ± 0.64 |

| 14: There is no one who shares my interests and concerns.b | 3.5 ± 0.67 |

| 15: There is no one who really relies on me for their wellbeing.b | 3.8 ± 0.50 |

| 16: There is a trustworthy person I could turn to for advice if I were having problems. | 3.6 ± 0.68 |

| 17: I feel a strong emotional bond with at least 1 other person. | 3.7 ± 0.57 |

| 18: There is no one I can depend on for aid if I really need it.b | 3.6 ± 0.71 |

| 19: There is no one I feel comfortable talking about problems with.b | 3.5 ± 0.74 |

| 20: There are people who admire my talents and abilities. | 3.3 ± 0.61 |

| 21: I lack a feeling of intimacy with another person.b | 3.3 ± 0.90 |

| 22: There is no one who likes to do the things I do.b | 3.5 ± 0.66 |

| 23: There are people who I can count on in an emergency. | 3.7 ± 0.60 |

| 24: No one needs me to care for them.b | 3.9 ± 0.44 |

Social Provisions 24-item scale (Cutrona and Russell 198722); 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). Social provisions assessed: guidance (Q3, 12, 16, 19), reassurance of worth (Q6, 9, 13, 20), social integration (Q5, 8, 14, 22), attachment (Q2, 11, 17, 21), nurturance (Q4, 7, 15, 24), reliable alliance (Q1, 10, 18, 23). Instrument is presented in its original format.

Items were reverse scored.

DISCUSSION

Work-family conflict has been extensively studied; however, we are unaware of previous researchers who have compared ATs in 2 of the most common practice settings. We are also unaware of any studies examining both WFC and social support in the same sample. Our findings uniquely contribute to the athletic training literature on WFC in several ways. First, we determined that the time demands of the profession were a major factor in WFC. Past investigators linked the long, irregular working hours of the AT to WFC,1,2 yet those groups used a scale that measures overall WFC experiences rather than the scale developed by Carlson et al,23 which assesses the 3 facets of WFC (time, strain, behavior). Our participants, much like those evaluated earlier,1,2 worked in excess of 40 hours per week, which explains why scale items linked to time-based conflict were rated higher. Athletic trainers working in the collegiate or secondary school setting typically are part of a sports or athletic organizational structure, which can commonly be characterized by a 24/7 mindset.24 Those working within this model often feel pressure to conform and be available and present at all times. Thus, conflict is inevitable: time during the day is insufficient for completing additional tasks outside the workplace, and we know that the more an AT works, the more WFC he or she experiences.25

It is interesting to note that our participants scored lower on the other 2 sources of conflict (strain, behavior). Although time demands appear to be universally experienced by the AT population, strain and behavior are likely unique to the individual. Strain and behavior may relate to a person's relationships, mentality, and personality and vary greatly among individuals. Similarly, these sources of conflict may also be inconsistent and more susceptible to change, depending on the specific stressors present for the AT. Therefore, strain and behavioral sources of conflict may fluctuate to a greater extent than time-based conflict.

Regarding time, our collegiate participants worked more hours during their busiest time of the year as compared with secondary school ATs. However, we did not find differences in WFC between these groups, as would be expected when a greater amount of time was spent at work.

Second, to our knowledge, no researchers have compared the 2 most common employment settings in the same sample. Mazerolle et al2,26 and Pitney et al19 examined WFC in these settings in separate studies, and although the same scales were used, a true comparison is not possible. The secondary school setting has been suggested as a family-friendly environment that may allow the AT to find balance among work, home, and family life.19 The rationale behind this was organizational policies (eg, workplace integration) and, in some cases, better working hours (ie, midafternoon, evening), more work schedule flexibility, and less travel. Yet our results suggested no difference in WFC by employment setting. Perhaps this was because time-based conflict was at a high level in both settings.

Third, sex was not a mediating factor of WFC. In fact, the scores for women and men, regardless of employment setting, were nearly identical. This result supports the growing literature that suggests sex is not a factor in WFC, particularly among ATs.2,24–26 The time-based factor, which facilitated WFC for our sample, likely negated sex as a factor in WFC, as ATs reported long work hours (60+ hours per week).2,3 In a recent systematic analysis,27 sex was not correlated with burnout despite differences in family status, education, or years of experience. Given the correlation between burnout and WFC, it is reasonable to assume that sex does not affect WFC, as highlighted by our findings. Still, although WFC scores were not different between sexes, the factors causing WFC in women and men may be different. One plausible explanation for our results was that we included only ATs with families, and having children, regardless of gender, can facilitate WFC.2 Today's reality is that both parents work, and men have to assume more responsibilities in their domestic partnerships, parenting, and household duties. Simultaneously, women must adjust to working longer hours and managing household and parenthood responsibilities. However, it is interesting that our results revealed differences in hours worked despite similar findings for WFC. This may indicate that women and men have different strategies for mitigating WFC or have different thresholds for WFC as related to their time spent in the workplace. Naugle et al28 found that men worked more hours than women, yet women had higher self-reported levels of burnout.

Fourth, we were able to quantifiably link the importance of social support to reduced WFC. Social support was recommended in the NATA position statement3 on facilitating work-life balance, and qualitative research has suggested its importance in alleviating WFC, but we are aware of no authors who have quantitatively linked social support to reduced WFC in ATs. Earlier investigators determined that higher levels of family instrumental and emotional support were associated with lower levels of family interference with work29 and that social support could reduce the chance that situations would be perceived as stressful, thereby indirectly alleviating WFC.30 In a recent meta-analysis,21 broader sources of support were more strongly related to WFC than specific sources of support and organizational support may have been the most important source of support overall. Our data suggest that, as an AT feels supported, his or her level of WFC reduces. Social support has been positively correlated with decreased WFC and identified as a buffer against other factors, such as burnout and decreased wellbeing.31 Researchers31,32 indicated that support should come from various individuals (eg, coworkers and friends) and not be limited to family or a spouse. “It takes a village” is a mantra that is often cited to encourage individuals to ask for help and manage their workloads, both at home and at work. It is important to note that we did not specifically ask participants to identify their forms, sources, or types of support, which would be warranted in future studies.

Limitations and Future Directions

To recruit collegiate ATs, we relied on a convenience sample, which is a limitation of our work. We explored WFC and social support among those ATs employed in the traditional collegiate and secondary school employment settings. In future research, the professional sports setting should be included along with more robust samples in other employment settings. This may allow for a perspective that highlights the unique roles and responsibilities of the ATs in those settings and their effects on these variables. Earlier authors used a short 5-item measure of WFC; we used a scale developed to assess the 3 main sources of WFC. Continued assessment using this more comprehensive tool will promote a better understanding of WFC in the athletic training profession as well as permit comparisons with our findings. Finally, we used a cross-sectional survey that can only speak to the experiences of our respondents at 1 timepoint. Future investigators should attempt to longitudinally examine WFC and support, as measures of these items can change with fluctuating demands during the academic seasons.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on our findings, time-based conflict appeared to supersede other facets of WFC conflict (strain and behavior based), which is understandable given the time demands of ATs. Interestingly, WFC did not differ between secondary school and collegiate ATs in our sample. We also did not find differences between mothers and fathers. These results emphasize the need for strategies to reduce WFC in both settings, which are the most common in the profession, and between sexes. In addition, social support networks can help to mitigate WFC and its subsequent negative effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the support of the Korey Stringer Institute at the University of Connecticut and the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) Athletic Training Locations and Services Project. Conclusions drawn from or recommendations based on the data they provided are ours and do not necessarily represent the official views of either organization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):194–205. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: facilitating work-life balance in athletic training practice settings. J Athl Train. 2018;53(8):796–811. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ, Burton LJ. Work-family conflict, part II: job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):513–522. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodman A, Mensch JM, Jay M, French KE, Mitchell MF, Fritz SL. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting. J Athl Train. 2010;45(3):287–298. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eberman LE, Kahanov L. Athletic trainer perceptions of life-work balance and parenting concerns. J Athl Train. 2013;48(3):416–423. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenhaus JH, Powell GN. When work and family are allies: a theory of work-family enrichment. Acad Manag Rev. 2006;31(1):72–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eason CM, Mazerolle SM, Denegar C, Pitney WA, McGarry J. Multilevel examination of job satisfaction and career intentions of collegiate athletic trainers: a quantitative approach. J Athl Train. 2018;53(1):80–87. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.11.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eason CM, Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Denegar C, McGarry J. An individual and organizational level examination of male and female collegiate athletic trainers' work-life interface outcomes: job satisfaction and career intentions. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2020;12(1):21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruening JE, Dixon MA. Work-family conflict in coaching II: managing role conflict. J Sport Manage. 2007;21(4):471–496. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Work-family conflict in coaching I: a top-down perspective. J Sport Manage. 2007;21(3):377–406. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Perspectives on work-family conflict in sport: an integrated approach. Sport Manage Rev. 2005;8(3):227–253. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pastore DL, Inglis S, Danylchuk KE. Retention factors in coaching and athletic management: differences by gender, position, and geographic location. J Sport Soc Issues. 1996;20(4):427–441. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahanov L, Loebsack AR, Masucci MA, Roberts J. Perspectives on parenthood and working of female athletic trainers in the secondary school and collegiate settings. J Athl Train. 2010;45(5):459–466. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM. Perceptions of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I female athletic trainers on motherhood and work-life balance: individual- and sociocultural-level factors. J Athl Train. 2015;50(8):854–861. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.5.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A. Factors influencing the decisions of male athletic trainers to leave the NCAA Division-I practice setting. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2013;18(6):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Trisdale WA. Work-life balance perspectives of male NCAA Division I athletic trainers: strategies and antecedents. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2015;7(2):50–62. [Google Scholar]

- 18.2018 salary survey findings. National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site. https://members.nata.org/members1/salarysurvey2018/2018-Salary-Survey-Whitepaper.pdf Published January 2019. Accessed February 14, 2020.

- 19.Pitney WA, Mazerolle SM, Pagnotta KD. Work-family conflict among athletic trainers in the secondary school setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):185–193. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazerolle SM, Ferraro EM, Eason CM, Goodman A. Factors and strategies contributing to the work-life balance of female athletic trainers employed in the NCAA Division I setting. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2013;5(5):211–222. [Google Scholar]

- 21.French KA, Dumani S, Allen TD, Shockley KM. A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and social support. Psychol Bull. 2018;144(3):284–314. doi: 10.1037/bul0000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlson DS, Kacmar KM, Williams LJ. Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. J Vocat Behav. 2000;56(2):249–276. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutrona CE, Russell DW. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Adv Pers Relation. 1987;1(1):37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruening JE, Dixon MA. Situating work-family negotiations within a life course perspective: insights on the gendered experiences of NCAA Division I head coaching mothers. Sex Roles. 2008;58(1–2):10–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eason CM, Mazerolle Singe SM, Rynkiewicz KM. Work-family guilt of collegiate athletic trainers: a descriptive study. Int J Athl Train Ther. 2019 doi: 10.1123/ijatt.2019-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Eason CM. Experiences of work-life conflict for the athletic trainer employed outside the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I clinical setting. J Athl Train. 2015;50(7):748–759. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.4.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cayton SJ, Valovich McLeod TC. Characteristics of burnout among collegiate and secondary school athletic trainers: a systematic review. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2019 doi: 10.3928/19425864-20190529-01. [DOI]

- 28.Naugle KE, Behar-Horenstein LS, Dodd VJ, Tillman MD, Borsa PA. Perceptions of wellness and burnout among certified athletic trainers: sex differences. J Athl Train. 2013;48(3):424–430. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams GA, King LA, King DW. Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work-family conflict with job and life satisfaction. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):411–420. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson DS, Perrewé PL. The role of social support in the stressor-strain relationship: an examination of work-family conflict. J Manage. 1999;25(4):513–540. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen TD. Family-supportive work environments: the role of organizational perceptions. J Vocat Behav. 2001;58(3):414–435. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanch A, Aluja A. Social support (family and supervisor), work-family conflict, and burnout: sex differences. Hum Relat. 2012;65(7):811–833. [Google Scholar]