Abstract

Background

The optimal dosage and administration approach of tranexamic acid (TXA) in primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) remains controversial. In light of recently published 14 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the study aims to incorporate the newly found evidence and compare the efficacy and safety of intra-articular (IA) vs. intravenous (IV) application of TXA in primary TKA.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library were searched for RCTs comparing IA with IV TXA for primary TKA. Primary outcomes included total blood loss (TBL) and drain output. Secondary outcomes included hidden blood loss (HBL), hemoglobin (Hb) fall, blood transfusion rate, perioperative complications, length of hospital stay, and tourniquet time.

Result

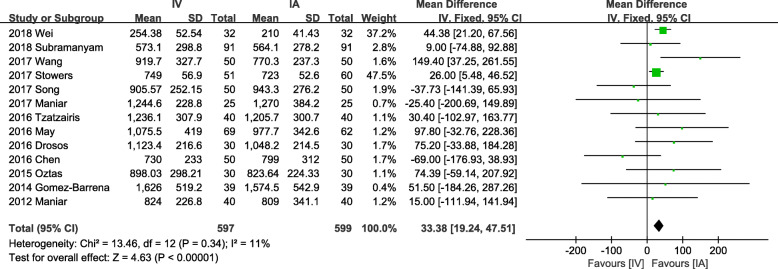

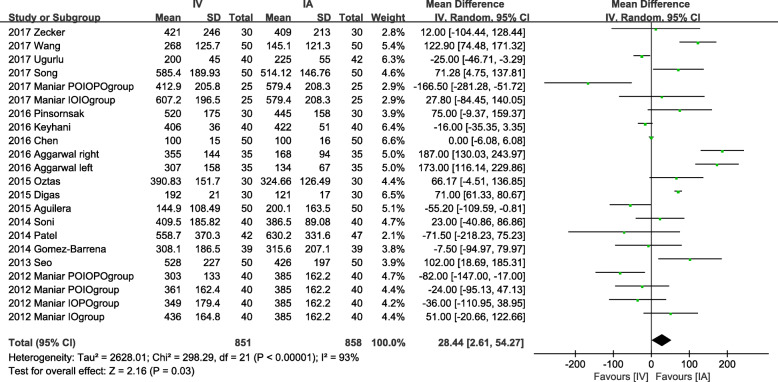

In all, 34 RCTs involving 3867 patients were included in our meta-analysis. Significant advantages of IA were shown on TBL (MD = 33.38, 95% CI = 19.24 to 47.51, P < 0.001), drain output (MD = 28.44, 95% CI = 2.61 to 54.27, P = 0.03), and postoperative day (POD) 3+ Hb fall (MD = 0.24, 95% CI = 0.09 to 0.39, P = 0.001) compared with IV. There existed no significant difference on HBL, POD1 and POD2 Hb fall, blood transfusion rate, perioperative complications, length of hospital stay, and tourniquet time between IA and IV.

Conclusion

Intra-articular administration of TXA is superior to intravenous in primary TKA patients regarding the performance on TBL, drain output, and POD3+ Hb fall, without increased risk of perioperative complications. Therefore, intra-articular administration is the recommended approach in clinical practice for primary TKA.

Keywords: Tranexamic acid, Total knee arthroplasty, Intra-articular administration, Intravenous administration

Background

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a common major orthopedic surgery, and the demand is still increasing due to human longevity and large population suffering from knee osteoarthritis (OA) around the world [1, 2].

TKA is an effective choice for end-stage OA [3]. But it is a major operation especially for the geriatric population, and the postoperative reduced hemoglobin (Hb) might require blood transfusion and potentially result in delayed physical rehabilitation, longer hospital stay, and higher medical cost [4].

Tranexamic acid (TXA) has been widely used in many orthopedic surgeries for controlling blood loss [5]. Its safety and efficacy has been validated by many studies [6–8]. However, the optimal administration approach for primary TKA remains to be investigated. Oral administration and intravenous (IV) administration have been validated as an effective approach, but there are potential risks of thromboembolic complications [9, 10]. Besides, intra-articular (IA) administration provides a maximum concentration at the bleeding site with limited systemic influence [11].

Gianakos et al. [12] published the latest meta-analysis on IA vs. IV in 2018, and it demonstrated the superiority of IA over IV administration. However, with the publication of 14 new randomized controlled trial (RCT) results thereafter [13–26], it is imperative to perform a new meta-analysis to corroborate or repudiate the conclusion of Gianakos et al., which is the purpose of our study.

Methods

Our meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement) [27]. We did not publish a protocol for this study.

Literature search

Four electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library were searched. Searching was conducted until April 20, 2020, with the following search terms: (“tranexamic acid” OR “TXA”) AND (“total knee arthroplasty” OR “total knee replacement” OR “TKA” ). Literatures were limited to English publication. All studies were full text available. Unpublished investigations were not included.

Selection criteria

Two independent reviewers performed the search, removed duplicate records, reviewed the titles and abstracts, and identified studies as included, excluded, or uncertain. Full-text articles were reviewed to determine eligibility if identified uncertain. Disagreements were discussed with a third reviewer.

We retrieved all RCTs that compared IA with IV administration of TXA in patients receiving primary TKA. Inclusion criteria were (1) patients who underwent primary TKA, (2) comparative studies of IA vs. IV administration of TXA, (3) availability of full text, and (4) English publications. Exclusion criteria were (1) non-cohort studies, (2) retrospective cohort studies, (3) reviews, and (4) unpublished studies.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted: characteristics of study (design, country, no. of patients, age, sex, body mass index, follow-up, and conclusion), method of administration and operation (IV or IA dosage, type of operation, and surgical approach), and surgical protocols (thromboprophylaxis, DVT screening, prosthetic properties, blood transfusion protocol, tourniquet application, and drainage).

Primary outcomes included total blood loss (TBL), which was calculated by the Gross formula or Hb balance method [28, 29], and drain output. Secondary outcomes included hidden blood loss (HBL), Hb fall, blood transfusion rate, and perioperative complications including deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), wound infection, and other vascular events. The duration of tourniquet application and length of hospital stay were also recorded and analyzed. Missing data were obtained from corresponding authors if possible.

Quality assessment

We assessed the qualities of included studies according to the criteria of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [30]. The strength of evidence for each major outcome was evaluated according to the 8-point modified Jadad scale (Table 1) [31]. A study scoring above 4 was considered qualified. A study scoring above or equal to 7 was considered as high-quality evidence.

Table 1.

Modified Jadad scale

| Item assessed | Score |

|---|---|

| Was the study described as randomized? | |

| Yes | + 1 |

| No | 0 |

| Was the method of randomization appropriate? | |

| Yes | + 1 |

| No | − 1 |

| Not described | 0 |

| Was the study described as blinded? | |

| Yes | + 1 |

| No | 0 |

| Was the method of blinding appropriate? | |

| Yes | + 1 |

| No | − 1 |

| Not described | 0 |

| Was there a description of withdrawals and dropouts? | |

| Yes | + 1 |

| No | 0 |

| Was there a clear description of the inclusion/exclusion criteria? | |

| Yes | + 1 |

| No | 0 |

| Was the method used to assess adverse effects described? | |

| Yes | + 1 |

| No | 0 |

| Was the method of statistical analysis described? | |

| Yes | + 1 |

| No | 0 |

Assessment of bias

The risk of bias in individual studies was divided into five parts: selection bias (random generation sequence and allocation concealment), performance and detection bias (blind), attrition bias (incomplete data), reporting bias (selective reporting), and other biases. Publication bias across studies would be shown by funnel plot if necessary.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed continuous data by mean difference (MD) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Odds ratio (OR) and its corresponding 95% CI were calculated for dichotomous data. We assessed heterogeneity by using the I2 statistic. I2 value above 50% was considered as high heterogeneity and a random-effects model would be used, while a value below 50% was considered as low heterogeneity and a fixed-effects model would be adopted [32]. Subgroup analyses would be considered when meeting high heterogeneity. Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.3 software. Forrest plots were used to describe the primary results of the meta-analysis. Funnel plots for primary outcomes (TBL and drain output) were generated to evaluate the potential publication bias. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Formal ethical approval was deemed not necessary in our meta-analysis.

Result

Search results

Figure 1 shows detailed steps of the literature search, in which 773 studies were reviewed: 698 studies were excluded after screening titles and abstracts, and the remaining 75 studies were reviewed in full text. After excluding 41 studies according to selection criteria, 34 studies encompassing 3867 patients were included in our study [13–26, 29, 33–51].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search

Study characteristics and quality assessments

As shown in Table 2, the sample size of the included studies ranged from 25 to 320, and the mean age of patients ranged from 57 to 73. Nine of the studies (9/34, 26.5%) favored IA administration, while four of the studies (4/34, 11.8%) preferred IV administration.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study

| Study | Design | Country | No. of patients | Age (years) | Sex (male/female) | BMI (kg/m2) | Follow-up | Conclusion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | IA | IV | IA | IV | IA | IV | IA | |||||

| Jules-Elysee et al. [14] | RCT | USA | 31 | 32 | 65.6 ± 8.4 | 65.0 ± 6.9 | 11/20 | 12/20 | 31.6 ± 7.1 | 31.1 ± 5.2 | Unclear | IV > IA |

| Laoruengthana et al. [13] | RCT | Thailand | 76 | 75 | 64.01 ± 7.68 | 64.81 ± 8.06 | 62/14 | 63/12 | 27.8 ± 5.2 | 27.6 ± 4.2 | Unclear | IA > IV |

| Zhang et al. [15, 52] | RCT | China | 50 | 50 | 63.12 ± 8.79 | 59.86 ± 12.01 | 12/38 | 10/40 | 23.9 ± 4.7 | 25.0 ± 4.3 | 6 months | IA > IV |

| Abdel et al. [20] | RCT | USA | 320 | 320 | 66 | 67 | 127/193 | 133/187 | 31.3 | 31.6 | Unclear | IV > IA |

| Ahmed et al. [23] | RCT | Pakistan | 70 | 70 | 63.30 ± 9.51 | 64.39 ± 9.07 | 28/42 | 32/38 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | IA > IV |

| López-Hualda et al. [21] | RCT | Spain | 30 | 30 | 73.1 ± 7.3 | 72.9 ± 7.1 | 6/24 | 11/19 | Unclear | Unclear | 1 year | IA > IV |

| George et al. [16] | RCT | India | 55 | 58 | 64.1 | 63.8 | 24/31 | 14/44 | 29.4 | 31.1 | 6 weeks | Neutral |

| Subramanyam et al. [19] | RCT | India | 91 | 91 | 62.9 ± 6.8 | 62.7 ± 7.5 | 31/60 | 35/56 | 28.9 | 29.9 | 6 weeks | Neutral |

| Wei et al. [18] | RCT | China | 32 | 32 | 66.47 ± 8.28 | 66.43 ± 7.69 | 14/18 | 16/16 | 32.4 ± 3.7 | 34.2 ± 5.0 | 3 months | Neutral |

| Goyal et al. [36] | RCT | Australia | 85 | 83 | 68.8 ± 7.4 | 66.7 ± 8.9 | 40/47 | 38/43 | 30.3 ± 6.1 | 31.0 ± 5.3 | 1 month | Neutral |

| Lacko et al. [22] | RCT | Slovakia | 30 | 30 | 68.4 ± 7.2 | 67.5 ± 7.7 | 12/18 | 13/17 | 31.1 ± 4.7 | 31.9 ± 4.7 | 3 months | IV > IA |

| Maniar et al. [33] | RCT | India | 50 | 25 | 65.7 ± 7.6 | 62.2 ± 7.1 | 7/43 | 2/23 | 30.2 ± 4.5 | 30.3 ± 3.9 | 3 months | Neutral |

| Prakash et al. [26] | RCT | India | 50 | 50 | 70.2 | 71 | NR | NR | Unclear | Unclear | 3 months | IV > IA |

| Song et al. [35] | RCT | South Korea | 50 | 50 | 69.2 ± 6.4 | 69.8 ± 6.8 | 6/44 | 8/42 | 26.52 ± 3.3 | 26.96 ± 4.2 | 3 months | Neutral |

| Stowers et al. [24] | RCT | New Zealand | 51 | 60 | 71 ± 8.6 | 70 ± 8.5 | 27/24 | 28/32 | 31.2 ± 5.5 | 31.2 ± 5.5 | 6 months | Neutral |

| Uğurlu et al. [34] | RCT | USA | 40 | 42 | 69.4 ± 7.5 | 70.6 ± 8.6 | 11/29 | 9/33 | 30.8 ± 5.3 | 31.1 ± 5.4 | 10 days | Neutral |

| Wang et al. [11, 23] | RCT | China | 50 | 50 | 67.42 ± 8.20 | 67.98 ± 5.97 | 14/36 | 14/36 | 26.7 ± 3.4 | 25.9 ± 3.8 | 5 weeks | IA > IV |

| Zekcer et al. [25] | RCT | Brazil | 30 | 30 | 65.7 | 65.7 | 6/24 | 9/21 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Neutral |

| Aggarwal et al. [39] | RCT | India | 35 | 35 | 58.77 ± 10.14 | 55.66 ± 8.71 | 13/22 | 12/23 | 26.33 ± 3.79 | 27.33 ± 4.63 | 6 months | IA > IV |

| Chen et al. [29, 53] | RCT | Singapore | 50 | 50 | 65 ± 8 | 65 ± 8 | 15/35 | 10/40 | 28 ± 5 | 28 ± 7 | 1 month | Neutral |

| Drosos et al. [38] | RCT | Greece | 30 | 30 | 69.27 ± 7.21 | 71.10 ± 6.32 | 6/24 | 6/24 | 32.79 ± 5.04 | 33.38 ± 6.08 | 1 month | Neutral |

| Keyhani et al. [42] | RCT | Iran | 40 | 40 | 68.4 ± 10.4 | 67 ± 11.9 | 26/14 | 23/17 | 32.7 ± 5.5 | 31.3 ± 5.4 | 2 weeks | Neutral |

| May et al. [37] | RCT | USA | 69 | 62 | 65.0 ± 9.6 | 63.0 ± 10.6 | 11/58 | 18/44 | 33.8 | 33.8 | 1 month | Neutral |

| Pinsornsak et al. [41] | RCT | Thailand | 30 | 30 | 69.97 ± 7.55 | 67.63 ± 7.96 | 7/23 | 5/25 | 26.52 ± 3.7 | 27.96 ± 4.99 | 2 weeks | Neutral |

| Tzatzairis et al. [40] | RCT | Greece | 40 | 40 | 69.55 ± 6.61 | 69.10 ± 8.68 | 9/31 | 7/33 | 32.60 ± 4.09 | 32.60 ± 4.50 | 6 weeks | Neutral |

| Aguilera et al. [43] | RCT | Spain | 50 | 50 | 72.49 ± 7.68 | 72.53 ± 6.60 | 38/12 | 32/18 | 30.20 ± 4.10 | 30.89 ± 4.37 | 2 months | Neutral |

| Digas et al. [44] | RCT | Greece | 30 | 30 | 70 ± 6.5 | 71 ± 7.0 | 2/28 | 7/23 | Unclear | Unclear | 1 year | IA > IV |

| Öztaş et al. [45] | RCT | Turkey | 30 | 30 | 68.56 | 67.06 | 5/25 | 4/26 | Unclear | Unclear | 3 months | IA > IV |

| Gomez-Barrena et al. [46] | RCT | Spain | 39 | 39 | 71.8 ± 10.3 | 70.1 ± 9.1 | 25/14 | 26/13 | 30.2 ± 4.2 | 30.4 ± 4.1 | 1 month | Neutral |

| Patel et al. [47] | RCT | USA | 42 | 47 | 64.9 ± 7.8 | 64.8 ± 9.7 | 10/32 | 13/34 | 35.8 ± 8.6 | 32.7 ± 7.0 | 2 weeks | Neutral |

| Sarzaeem et al. [48] | RCT | Iran | 50 | 100 | 66.9 ± 7.2 | 67.8 ± 7.2 | 7/43 | 13/87 | 31.6 ± 2.7 | 31.5 ± 3.4 | Unclear | Neutral |

| Soni et al. [49] | RCT | India | 40 | 40 | 69.05 ± 4.10 | 69.45 ± 4.71 | 19/21 | 17/23 | Unclear | Unclear | 6 weeks | Neutral |

| Seo et al. [50] | RCT | South Korea | 50 | 50 | 66.8 ± 6.3 | 67.5 ± 6.6 | 6/44 | 5/45 | 28.1 ± 3.1 | 27.8 ± 3.5 | 2 months | IA > IV |

| Maniar et al. [51] | RCT | India | 160 | 40 | 67.4 ± 8.1 | 67.4 ± 7.9 | 36/124 | 6/34 | 29.2 ± 5.4 | 30.9 ± 5.2 | 3 months | Neutral |

RCT randomized controlled trial, IV intravenous group, IA intra-articular group, TKA total knee arthroplasty, BMI body mass index

Methods of administration and types of operation are presented in Table 3. One study (Maniar et al.) included four IV groups and another study (Maniar et al.) included two IV groups [33, 51]. One study (Sarzaeem et al.) had two IA groups with different dosages [48]. Unilateral TKA was performed in 31 studies (31/34, 91.2%) while bilateral TKA was performed in three studies (31/34, 8.8%). Twenty-four studies (24/34, 70.6%) adopted medial parapatellar, four (4/34, 11.8%) chose the midvastus approach, and two studies (2/34, 5.9%) used subvastus parapatellar, while the approach was unclear in the rest six studies (6/34, 17.6%).

Table 3.

Methods of administration and operation

| Study | IV dosage | IA dosage | Type of operation | Surgical approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jules-Elysee et al. [14] | 1 g TXA × two doses; POPO | 3 g TXA × one dose; before tourniquet release | Primary unilateral TKA | Unclear |

| Laoruengthana et al. [13] | 10 mg/kg TXA × one dose; IO | 15 mg/kg TXA × one dose; before closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Zhang et al. [15, 52] | 20 mg/kg TXA × one dose; PEO | 3 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Abdel et al. [20] | 1 g TXA × one dose; PEO | 3 g TXA × one dose; after cemented | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar or midvastus approach |

| Ahmed et al. [17] | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; PTO | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; while closure | Primary simultaneous bilateral TKA | Unclear |

| López-Hualda et al. [21] | 1 g TXA × one dose; PEO | 1 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| George et al. [16] | 10 mg/kg TXA × two doses; POPO | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; before closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Subramanyam et al. [19] | 10 mg/kg TXA × one dose; PEO | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Wei et al. [18] | 10 mg/kg TXA × one dose; PEO | 1 g TXA × one dose; before tourniquet release | Primary unilateral TKA | Unclear |

| Goyal et al. [36] | 1 g TXA × three doses; IO/PTO/PTO | 3 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Lacko et al. [22] | 10 mg/kg TXA × two doses; POPO | 3 g TXA × one dose; after cemented | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Maniar et al. [33] | 10 mg/kg TXA × two doses (bilateral); IO | 3 g TXA × two doses(bilateral); after cemented | Primary simultaneous bilateral TKA | Midvastus approach |

| 10 mg/kg TXA × three doses; POIOPO | ||||

| Prakash et al. [26] | 10 mg/kg TXA × three doses; POIOPO | 3 g TXA × one dose; before closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Song et al. [35] | 10 mg/kg TXA × three doses; POIOPO | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary bilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Stowers et al. [24] | 1 g TXA × one dose; IO | 1 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Uğurlu et al. [34] | 20 mg/kg TXA × one dose; PEO | 3 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Wang et al. [11, 23] | 1 g TXA × one dose; IO | 1 g TXA × one dose; before closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Zekcer et al. [25] | 20 mg/kg TXA × one dose; unclear | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; before tourniquet release | Primary unilateral TKA | Unclear |

| Aggarwal et al. [39] | 15 mg/kg TXA × two dose; IOPO | 15 mg/kg TXA × one dose; before closure | Primary simultaneous bilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Chen et al. [29, 53] | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; IO | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; after cemented | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Drosos et al. [38] | 1 g TXA × one dose; PEO | 1 g TXA × one dose; before closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Keyhani et al. [42] | 0.5 g TXA × one dose; IO | 1.5 g TXA × two doses; before/after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| May et al. [37] | 1 g TXA × two doses; POPO | 2 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Unclear |

| Pinsornsak et al. [37] | 0.75 mg TXA × one dose; IO | 0.75 mg × one dose; before tourniquet release | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Tzatzairis et al. [40] | 1 g TXA × one dose; PEO | 1 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Aguilera et al. [43] | 1 g TXA × two doses; POIO | 1 g TXA × one dose; after cemented | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Digas et al. [44] | 15 mg/kg TXA × one dose; IO | 2 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Öztaş et al. [45] |

15 mg/kg TXA × two doses; POPO 10 mg/kg TXA × one dose; 1-h infusion |

2 g TXA × one dose; before tourniquet release | Primary unilateral TKA | Unclear |

| Gomez-Barrena et al. [46] | 15 mg/kg TXA × two doses; IOPO | 3 g TXA × one dose; before + after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Patel et al. [47] | 10 mg/kg TXA × one dose; IO | 2 g TXA × one dose; before tourniquet release | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial or subvastus parapatellar |

| Sarzaeem et al. [48] | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; PTO | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; after closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Subvastus approach |

| 3 g TXA × one dose; before closure | ||||

| Soni et al. [49] | 10 mg/kg TXA × three doses; POIOPO | 3 g TXA × one dose; before tourniquet release | Primary unilateral TKA | Midvastus approach |

| Seo et al. [50] | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; PTO | 1.5 g TXA × one dose; while closure | Primary unilateral TKA | Medial parapatellar |

| Maniar et al. [51] | 10 mg/kg TXA × one dose; IO | 3 g TXA × one dose; before tourniquet release | Primary unilateral TKA | Midvastus approach |

| 10 mg/kg TXA × two doses; IOPO | ||||

| 10 mg/kg TXA × two doses; POIO | ||||

| 10 mg/kg TXA × three doses; POIOPO |

IO intraoperative dose, IOPO intra- and postoperative doses, PEO preoperative dose, POIO pre- and intraoperative doses, POIOPO all three doses, POPO pre- and postoperative doses, PTO postoperative dose, TXA tranexamic acid

Table 4 summarizes the detailed surgical protocols. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) was the preferred prophylactic choice for thrombosis (21/34, 61.8%), following by pumping exercise and compression stocking (7/34, 20.6%), and aspirin (6/34, 17.6%). Both Doppler ultrasound and clinical examination were the most commonly used screening method for DVT (16/34, 47.1%), and chest CT was used in five studies (5/34, 14.7%), while nine (9/34, 26.5%) remained unclear. Cemented prosthesis was adopted in 27 studies (27/34, 79.4%), tourniquet was used in 31 studies (31/34, 91.2%), and 19 of the studies (31/34, 55.9%) clamped the drain tube after the operation.

Table 4.

Surgical protocols

| Study | Thromboprophylaxis | DVT screening method | Prosthetic properties | Blood transfusion protocol | Tourniquet | Drainage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jules-Elysee et al. [14] | Unclear | Unclear | Cemented | Unclear | Yes | Clamped for 4 h |

| Laoruengthana et al. [13] | LMWH/warfarin | Unclear | Cemented | Hb < 9.0 g/L | Yes | Clamped for 3 h |

| Zhang et al. [15, 52] | Rivaroxaban | Doppler ultrasound | Cemented | Unclear | Yes | Unclear |

| Abdel et al. [20] | Aspirin/warfarin | Unclear | Cemented |

Hb < 7.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Unclear |

| Ahmed et al. [17] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| López-Hualda et al. [21] | Unclear | Unclear | Cemented | Hb < 8.0 g/dL + symptoms | Yes | Unclear |

| George et al. [16] | LMWH/aspirin | Doppler ultrasound | Cemented | Hb < 7.0 g/dL | Yes | Unclear |

| Subramanyam et al. [19] |

Aspirin Calf pump |

Clinical examination Doppler ultrasound |

Cemented |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | No drain |

| Wei et al. [18] | LMWH | Unclear | Cemented |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Unclear |

| Goyal et al. [36] | LMWH/aspirin Compression stocking | Doppler ultrasound | Hybrid |

Hb < 7.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

No | Closed |

| Lacko et al. [22] | Unclear | Doppler ultrasound | Cemented |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 9.0 + symptoms |

Yes | Unclear |

| Maniar et al. [33] |

LMWH Ankle pumping exercise Compression stocking |

Clinical examination Doppler ultrasound |

Cemented |

Hn < 8.5 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Clamped for 2 h |

| Prakash et al. [26] |

LMWH Calf pump |

Doppler ultrasound Chest CT |

Cemented | Hb < 8.0 g/dL | Yes | Clamped for 30 min |

| Song et al. [35] | LMWH in high-risk patient |

Doppler ultrasound Chest CT |

Cemented | Hb < 8.0 g/dL | Yes | Clamped for 10 min |

| Stowers et al. [24] | Aspirin | Clinical examination | Cemented |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | No drain |

| Uğurlu et al. [34] |

LMWH Compression stocking |

Clinical examination | Unclear |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb > 8.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Clamped for 1 h |

| Wang et al. [11, 23] |

LMWH/rivaroxaban Elastic bandage |

Doppler ultrasound | Cemented |

Hb < 6.0 g/dL Hb > 6.0 + symptoms |

Yes | Clamped for 2 h |

| Zekcer et al. [25] |

LMWH Compression stocking |

Unclear | Cemented | Hb < 8.0 g/dL | Yes | Unclear |

| Aggarwal et al. [39] | Aspirin | Clinical examination | Cemented | Hb > 8.0 g/dL + symptoms | Yes | Clamped for 1 h |

| Chen et al. [29, 53] |

LMWH Calf pumps |

Clinical examination Doppler ultrasound Chest CT |

Cemented |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Unclear |

| Drosos et al. [38] |

LMWH Compression stocking |

Clinical examination Doppler ultrasound |

Hybrid | Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms | Yes | No clamp |

| Keyhani et al. [42] | LMWH | Doppler ultrasound | Cemented | Hb < 8.0 g/dL | Yes | Clamped for 2 h |

| May et al. [37] |

LMWH Sequential compression |

Clinical examination | Unclear |

Hb < 7.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | No drain |

| Pinsornsak et al. [37] |

Ankle pumping exercise Early ambulation |

Clinical examination | Cemented | Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms | Yes | Clamped for 3 h |

| Tzatzairis et al. [40] |

LMWH Compression stocking |

Doppler ultrasound Clinical examination Chest CT |

Cemented | Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms | No | Clamped for 1 h |

| Aguilera et al. [43] | LMWH | Clinical examination | Cemented |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 9.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Clamped for 1 h |

| Digas et al. [44] | Tinzaparin | Clinical examination | Cemented |

Hb < 8.5 g/dL Hb < 9.5 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Clamped for 3 h |

| Öztaş et al. [45] | LMWH | Clinical examination | Unclear |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Clamped for 30 min |

| Gomez-Barrena et al. [46] | LMWH |

Clinical examination Doppler ultrasound |

Cemented |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Clamped for 2 h |

| Patel et al. [47] | LMWH | Doppler ultrasound Chest CT | Unclear | Hb < 8.0 g/dL + symptoms | Yes | Yes |

| Sarzaeem et al. [48] | Unclear | Unclear | Cemented |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Clamped for 1 h |

| Soni et al. [49] |

LMWH Ankle pumping exercise |

Clinical examination | Cemented | Hb < 8.0 g/dL | Yes | Clamped for 1 h |

| Seo et al. [50] | Unclear | Unclear | Cemented |

Hb < 8.0 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | No drain |

| Maniar et al. [51] |

LMWH Ankle pumping exercise Compression stocking |

Clinical examination Doppler ultrasound |

Cemented |

Hb < 8.5 g/dL Hb < 10.0 g/dL + symptoms |

Yes | Clamped for 2 h |

Hb hemoglobin, LMWH low-molecular-weight heparin

Quality assessment and assessment of bias are presented in Table 5. In all, 25 studies (25/34, 73.5%) are high-quality and nine (9/34, 26.5%) are moderate-quality evidences.

Table 5.

Methodological quality of included studies

| Study | Quality score | Random generation sequence | Allocation concealment | Blind | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other biases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jules-Elysee et al. [14] | 7 | Computer-generated randomization schedule | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No |

| Laoruengthana et al. [13] | 8 | Computer-generated numbers | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Zhang et al. [15, 52] | 8 | Randomized numbers table | Labeled with numbering code | Yes | No | No | No |

| Abdel et al. [20] | 6 | Randomized but unknown method | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No |

| Ahmed et al. [17] | 6 | The lottery method | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| López-Hualda et al [21] | 5 | Randomized but unknown method | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| George et al. [16] | 8 | Computer-generated numbers | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Subramanyam et al. [19] | 8 | Computer-generated numbers | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Wei et al. [18] | 8 | Randomized numbers table | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Goyal et al. [36] | 8 | Computer-generated numbers | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Lacko et al. [22] | 6 | Computer-generated numbers | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Maniar et al. [33] | 8 | Randomly drawing sealed envelope from container | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Prakash et al. [26] | 7 | Randomized but unknown method | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Song et al. [35] | 8 | Computer-generated numbers | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Stowers et al. [24] | 8 | Block randomization | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Uğurlu et al. [34] | 5 | Randomized but unknown method | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Wang et al. [11, 23] | 8 | Randomly drawing sealed envelope from container | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Zekcer et al. [25] | 8 | Randomly drawing sealed envelope from container | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Aggarwal et al. [39] | 8 | Computer-generated numbers | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Chen et al. [29, 53] | 8 | Randomized numbers table | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Drosos et al. [38] | 8 | Stratified randomization by minimization | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Keyhani et al. [42] | 5 | Randomized but unknown method | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| May et al. [37] | 7 | Randomized numbers table | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No |

| Pinsornsak et al. [37] | 7 | Randomized but unknown method | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Tzatzairis et al. [40] | 6 | Stratified randomization by minimization | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Aguilera et al. [43] | 7 | Randomized numbers table | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No |

| Digas et al. [44] | 7 | Randomized but unknown method | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Öztaş et al. [45] | 5 | Randomized but unknown method | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Gomez-Barrena et al. [46] | 7 | Randomized but unknown method | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

| Patel et al. [47] | 7 | Excel’s randomization | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No |

| Sarzaeem et al. [48] | 7 | Randomized numbers table | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No |

| Soni et al. [49] | 6 | Computer-generated numbers | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Seo et al. [50] | 7 | Randomized numbers table | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No |

| Maniar et al. [51] | 8 | Randomly drawing sealed envelope from container | Concealed envelope | Yes | No | No | No |

Meta-analysis of outcomes

All the results are listed in Table 6, including primary outcomes, secondary outcomes, three subgroup analyses, and three low heterogeneity analyses.

Table 6.

Results of meta-analysis and subgroup analyses

| Variables | Studies (n) | Patients (n) | P value | Incidence: OR/MDs (95% CI) | Heterogeneity: P value (I2) | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total blood loss (TBL) | 18 | 1656 | < 0.001* | 63.99 (27.81 to 100.16) | < 0.001* (81%) | Random |

| 13 | 1197 | < 0.001* | 33.38 (19.24 to 47.51) | 0.34 (11%) | Fixed | |

| Drain output | 17 | 1494 | 0.03* | 28.44 (2.61 to 54.27) | < 0.001* (93%) | Random |

| Clamp < 2 h | 7 | 607 | 0.03* | 51.47 (6.02 to 96.92) | < 0.001* (92%) | Random |

| Clamp ≥ 2 h | 10 | 887 | 0.51 | 12.40 (− 24.85 to 49.65) | < 0.001* (89%) | Random |

| Hidden blood loss (HBL) | 6 | 640 | 0.83 | 7.57 (− 60.34 to 75.47) | 0.006 (69%) | Random |

| Hemoglobin (Hb) fall | 19 | 1749 | 0.79 | − 0.02 (− 0.20 to 0.16) | < 0.001* (87%) | Random |

| POD1 | 10 | 1052 | 0.07 | − 0.34 (− 0.70 to 0.02) | < 0.001* (91%) | Random |

| 8 | 839 | 0.86 | − 0.01 (− 0.11 to 0.13) | 0.14 (36%) | Fixed | |

| POD2 | 8 | 701 | 0.37 | 0.17 (− 0.20 to 0.53) | <0.001* (82%) | Random |

| 6 | 531 | 0.36 | − 0.08 (− 0.25 to 0.09) | 0.11 (44%) | Fixed | |

| POD3+ | 6 | 637 | 0.001* | 0.24 (0.09 to 0.39) | 0.18 (34%) | Fixed |

| Transfusion rate | 25 | 2950 | 0.62 | 0.93 (0.69 to 1.24) | 0.54 (0%) | Fixed |

| Complications | 20 | 2594 | 0.98 | 1.00 (0.72 to 1.39) | 0.47 (0%) | Fixed |

| DVT | 10 | 1641 | 0.83 | 0.92 (0.44 to 1.92) | 0.84 (0%) | Fixed |

| PE | 3 | 342 | 0.98 | 1.02 (0.25 to 4.20) | 0.81 (0%) | Fixed |

| Wound complications | 14 | 1465 | 0.83 | 0.95 (0.58 to 1.55) | 0.39 (6%) | Fixed |

| Other adverse events | 13 | 1899 | 0.69 | 1.10 (0.68 to 1.80) | 0.42 (2%) | Fixed |

| Length of stay | 7 | 748 | 0.33 | 0.07 (− 0.07 to 0.22) | 0.35 (11%) | Fixed |

| Tourniquet time | 9 | 816 | 0.19 | − 1.22 (− 3.06 to 0.62) | 0.74 (0%) | Fixed |

POD postoperative day, DVT deep vein thrombosis

*≤ 0.05

Total blood loss

Eighteen studies provided valid data of TBL on 1656 patients. Given the presence of significant heterogeneity among studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 81%), we used a random-effects model for analysis. IA administration showed a significant advantage compared to IV administration (MD = 63.99, 95% CI = 27.81 to 100.16, P < 0.001). Concerning about the high heterogeneity, we performed a sensitivity analysis based on the risk of bias and got another lower heterogeneity result (Fig. 2) by analyzing 13 studies (P = 0.34, I2 = 11%) with a fixed-effects model, which still revealed a significant superiority of IA administration (MD = 33.38, 95% CI = 19.24 to 47.51, P < 0.001). Publication bias is shown by a funnel plot (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing low heterogeneity effect of IV vs IA TXA on total blood loss

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of TBL shows low publication bias

Drain output

Seventeen studies involving 1494 patients provided valid data of drain output. Due to significant heterogeneity among studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 93%), we used a random-effects model for analysis. IA administration showed a significant advantage (Fig. 4) compared to IV administration (MD = 28.44, 95% CI = 2.61 to 54.27, P = 0.03).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing the effect of IV vs IA TXA on drain output

Drainage volume was analyzed in subgroup based on the duration of tube clamping. For studies in which the drainage tube was clamped postoperatively less than two hours, a significant superiority was shown in the IA group compared to the IV group (MD = 51.47, 95% CI = 6.02 to 96.92, P = 0.03). Considering the high heterogeneity (P < 0.001, I2 = 92%), a random-effects was used for analysis. There was no significant difference (MD = 12.40, 95% CI = − 24.85 to 49.65, P = 0.51) for studies in which the drainage tube was clamped postoperatively over 2 h with high heterogeneity (P < 0.001, I2 = 89%).

Hidden blood loss

Only six studies including 640 patients reported HBL. Since there existed significant heterogeneity among studies (P = 0.006, I2 = 69%), we used a random-effects model for analysis. There existed no significant difference between the IV and IA groups (MD = 7.57, 95% CI = − 60.34 to 75.47, P = 0.83) on HBL.

Hemoglobin fall

In all, 19 studies involving 1749 patients reported the data of postoperative Hb fall. Because different studies reported Hb of postoperative day (POD) 1 to 5 with high heterogeneity (P < 0.001, I2 = 87%), we conducted subgroup analyses based on POD1, POD2, or POD3+.

Ten studies involving 1052 patients reported the POD1 Hb fall. The random-effects model (P < 0.001, I2 = 91%) was used for analysis, and there was no significant difference between the IV and IA groups (MD = − 0.34, 95% CI = − 0.70 to 0.02, P = 0.07). Regarding the high heterogeneity, a sensitivity analysis was performed and two studies were excluded [14, 48], then we got a lower heterogeneity result (P = 0.14, I2 = 36%) by analyzing the rest of 8 studies including 839 patients with a fixed-effects model. No significant difference was shown between the IV and IA groups (MD = − 0.01, 95% CI = − 0.11 to 0.13, P = 0.86).

Eight studies involving 701 patients reported the POD2 Hb fall. Considering the significant heterogeneity among studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 82%), we used a random-effects model for analysis. There existed no significant difference between the IV and IA groups (MD = 0.17, 95% CI = − 0.20 to 0.53, P = 0.37). We also performed a sensitivity analysis based on the risk of bias and excluded two studies [23, 39] and got a lower heterogeneity (P = 0.11, I2 = 44%) result by analyzing the rest of six studies involving 531 patients with a fixed-effects model. No significant difference was shown between the IV and IA groups (MD = − 0.08, 95% CI = − 0.25 to 0.09, P = 0.36).

Six studies involving 637 patients reported the POD3+ Hb fall. Because of low heterogeneity among studies (P = 0.18, I2 = 34%), a fixed-effects model was used for analysis. The IA group showed a significant advantage compared to the IV group (MD = 0.24, 95% CI = 0.09 to 0.39, P = 0.001).

Blood transfusion rate

Twenty-eight studies involving 3270 patients had data on blood transfusion. Transfusions were reported as 109/1664 (6.6%) in the IV group and 99/1606 (6.2%) in the IA group. Only 25 studies with 2950 patients were included in our meta-analysis, while the other three studies reported no transfusion event. The risk of a blood transfusion was similar between the two groups (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.69 to 1.24, P = 0.62), and the data showed low heterogeneity (P = 0.54, I2 = 0%).

Complications

In our study, certain complications were our concern, including DVT, PE, wound complications, and other adverse events. In all, 33 studies involving 3807 patients mentioned data of complications. The incidence of complications was mentioned as 77/1946 (4.0%) in the IV group and 77/1861 (4.1%) in the IA group. In these 33 studies, 13 of them reported no complication, so only 20 studies with 2594 patients were included in the meta-analysis. The risk was the same between the two groups (OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.72 to 1.39, P = 0.98) with low heterogeneity (P = 0.47, I2 = 0%).

In subgroup analysis, complications were classified into four types: DVT, PE, wound complications, and other adverse events. All subgroups showed insignificant differences between the IV and IA groups.

There were 23 DVT events reported in ten studies among all 33 studies. Pooled results showed a similar risk (OR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.44 to 1.92, P = 0.83) with low heterogeneity (P = 0.84, I2 = 0%). Both the IV and IA groups had four PE events reported in three studies [15, 24, 37]. The risk of PE was similar between the IV group and IA group (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.25 to 4.20, P = 0.98) with low heterogeneity (P = 0.81, I2 = 0%).

Wound complications included infection, necrosis, delay healing, and dehiscence. There were 58 wound complications reported in 14 studies. A fixed-effects model was used due to low heterogeneity (P = 0.39, I2 = 6%), and a similar risk of wound complications was shown in two groups (OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.58 to 1.55, P = 0.83 ).

Other adverse events were reported in 65 patients of 13 studies. Zhang et al. [15] reported 14 patients with idiopathic venous thromboembolism, and Wang et al. [23] reported one patient with intramuscular vein thrombosis. Besides, Abdel et al. [20] reported one patient with a thrombotic cerebrovascular accident. Functional disorders, such as stiffness, vomiting, nausea, dizziness, constipation, and paresthesia, were also reported in several studies [36, 43, 46]. A similar risk was shown (OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 0.68 to 1.80, P = 0.69) with low heterogeneity (P = 0.42, I2 = 2%) between IA and IV.

Length of hospital stay

Seven studies involving 748 patients reported data on length of hospital stay. Because of low heterogeneity (P = 0.35, I2 = 11%), we used a fixed-effects model for analysis. There was no significant difference in this comparison (MD = 0.07, 95% CI = − 0.07 to 0.22, P = 0.33).

Duration of tourniquet application

Nine studies including 815 patients reported data of tourniquet time. A fixed-effects model was used for analysis due to the low heterogeneity (P = 0.74, I2 = 0%). It did not show a statistical difference between the two groups (MD = − 1.22, 95% CI = − 3.06 to 0.62, P = 0.19).

Discussion

The most important finding in our study is that the difference of TBL and drain output between IV and IA administration is supported by newly added RCTs. Based on available evidences, the IA group shows significant superiority over the IV group regarding TBL, drain output, and POD3+ Hb fall. Besides, this study suggests that there exists no statistical difference on HBL, POD1 and POD2 Hb fall, incidence of blood transfusion, length of hospital stay, and time of tourniquet application between the two groups.

As an antifibrinolytic agent, TXA is a synthetic derivative of the amino acid lysine which competitively blocks the lysine-binding sites in the plasmin and plasminogen activator molecules, thereby preventing dissolution of the fibrin clot [54]. A previous study [6], which included 23,236 patients undergoing primary TKA, proved that TXA application was associated with decreased blood loss and transfusion risk without noticeably increased risk of complications. Besides, it could also reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism [6]. Several previous studies have compared IV and IA administration in TKA: Xie et al. [55] included 18 RCTs and found no significant difference between IV and IA. Gianakos et al. [12] included 18 RCTs and 5 non-RCTs, and they found significant differences regarding TBL and drain output between IV and IA. However, it was a study of high heterogeneity. Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis with more newly published RCTs. Moreover, subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis were performed to reach a more convincing conclusion.

In our study, IA administration shows significant superiority on the TBL to IV group (MD = 33.38, P < 0.001). A previous study indicated easier administration of topical TXA with a maximum concentration at the bleeding site and minimal systemic absorption [53], and therefore, topical application may deliver better blood loss control theoretically. The IA group also shows significant superiority on drain output (MD = 28.44, P = 0.03). The difference is more significant when the drainage tube is clamped postoperatively less than 2 h (MD = 51.47, P = 0.03). However, when the drainage tube is clamped over 2 h after surgery, there exists no statistical difference between them (P = 0.51). It is possibly due to a higher concentration of TXA and longer contact time in the IA approach.

There exists a significant difference on POD3+ Hb fall (MD = 0.24, P = 0.001), while POD1 (P = 0.86) and POD2 Hb fall (P = 0.36) show no noticeable difference between the two groups. POD3+ Hb fall is usually caused by HBL [55]. However, due to the limited data, there exists no difference on HBL (P = 0.83). Besides, IV administration of TXA has a maximal systemic absorption which may result in a shorter efficacy time in theory [56]. Therefore, it is a reasonable explanation of similar effects on POD1 and POD2, and a better result in the IA group on POD3+.

Fillingham et al. [5] published a clinical guideline of TXA application in joint replacement, but no optimal approach was recommended. In contrast, in our study, IA was found to be of superior value in light of the recently published RCT results. Although we have not compared IA with oral or combined administration, future clinical trials might validate our findings and possibly influence the revision of the clinical guideline of TXA. Besides, Fillingham et al. [5] also admitted dosage amount and multiple doses of TXA did not significantly affect the blood loss. However, several recent studies had different conclusions. Tzatzairis et al. [57] made a comparison between one to three doses of 15 mg/kg TXA intravenously and concluded that the three-dose group displayed better outcome. Lei et al. [58] reach the same conclusion by comparing 20 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg TXA intravenously. Moreover, Zhang et al. [52] even reported a better outcome of six-dose IV TXA. Besides, Tammachote et al. [59] compared high dosage (3 g) with low dosage (0.5 g) for IA TXA and also found a better outcome of high dosage. All the results of recent RCTs favor high-dose administration of TXA. Although TXA dosage and timing were popular topics, there is no meta-analysis about them by now. In our meta-analysis, there existed no standard dosage protocol for included studies (Table 3): In the IV group, 52.9% of the studies (18 studies) used a weight-based dosage (10 to 20 mg/kg) and the rest 47.1% of the studies (16 studies) chose a standard dosage (0.5 to 1.5 g). In the IA group, only 5.9% of the studies (2 studies) used a weight-based dosage (15 mg/kg) and the rest 94.1% of the studies (32 studies) chose a standard dosage (0.75 to 3 g). However, restricted by limited data, we did not perform a subgroup analysis for TXA dose and timing.

Advantages of our study include substantial high-quality RCTs (Table 5) and adequate analysis. 73.5% of the studies (25 studies) have detailed random generation sequence, and 55.9% of the studies (19 studies) have adequate allocation concealment. Besides, 73.5% of the studies (25 studies) are recent studies (published after 2015). Our analyzing methods are subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis when the previous analysis has high heterogeneity.

There are several limitations in our studies. Firstly, the inherent bias in different studies because of the inconsistent threshold for blood transfusion cannot be overlooked. Besides, the DVT rate might be influenced by the inclusion criteria, and the RCT of TXA in a DVT high-risk population might be required to validate our findings. Furthermore, repeated dose seemed a better choice than a single dose in both IV and IA administration [52, 57–59], and therefore, different methods of administration may influence the result. Lastly, data for HBL, length of hospital stay, and duration of tourniquet application are limited for analysis, and cost-effectiveness remains to be investigated.

Conclusion

IA administration of TXA is superior to IV TXA in patients receiving primary TKA regarding the performance on TBL, drain output, and POD3+ Hb fall, without noticeably increased risk of complications. Therefore, IA administration should be the preferred approach in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- IA

Intra-articular

- IV

Intravenous

- TXA

Tranexamic acid

- TKA

Total knee arthroplasty

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- TBL

Total blood loss

- HBL

Hidden blood loss

- POD

Postoperative day

- DVT

Deep vein thrombosis

- PE

Pulmonary embolism

- LMWH

Low-molecular-weight heparin

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- BMI

Body mass index

- OR

Odds ratio

- MD

Mean difference

- CI

Confidence interval

Authors’ contributions

PH* is in charge of the main idea and is the guarantor of the integrity of the entire study; JL and RKL contributed equally to this manuscript. JL and RKL are in charge of the study concepts, design, manuscript preparation, and editing; PH and SR are in charge of the language polishing and the grammar revision; RHZ and XT are in charge of the collection of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Nature Science Foundation of Hubei Province [2018CFB590]. The foundation had no roles in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

We state that the data will not be shared because all the raw data are present in the figures included in the article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jin Li and Ruikang Liu contributed equally to this work and are the co-first authors.

References

- 1.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, et al. International survey of primary and revision total knee replacement. Int Orthop. 2011;35(12):1783–1789. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1235-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780–785. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200704000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussain SM, Neilly DW, Baliga S, Patil S, Meek R. Knee osteoarthritis: a review of management options. Scott Med J. 2016;61(1):7–16. doi: 10.1177/0036933015619588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spahn DR. Anemia and patient blood management in hip and knee surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:482–495. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e08e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fillingham YA, Ramkumar DB, Jevsevar DS, et al. Tranexamic acid use in total joint arthroplasty: the clinical practice guidelines endorsed by the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Hip Society, and Knee Society. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3065–3069. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallstrom B, Singal B, Cowen ME, Roberts KC, Hughes RE. The Michigan experience with safety and effectiveness of tranexamic acid use in hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(19):1646–1655. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fillingham YA, Ramkumar DB, Jevsevar DS, et al. The safety of tranexamic acid in total joint arthroplasty: a direct meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3070–3082. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fillingham YA, Ramkumar DB, Jevsevar DS, et al. The efficacy of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a network meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3090–3098. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo P, He Z, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(18):587. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W, Yang C, Huang X, Liu R. Tranexamic acid reduces occult blood loss, blood transfusion, and improves recovery of knee function after total knee arthroplasty: a comparative study. J Knee Surg. 2018;31(3):239–246. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1602248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S, Gao X, An Y. Topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int Orthop. 2017;41(4):739–748. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3296-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gianakos AL, Hurley ET, Haring RS, Yoon RS, Liporace FA. Reduction of blood loss by tranexamic acid following total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. JBJS Rev. 2018;6(5):1. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laoruengthana A, Rattanaprichavej P, Rasamimongkol S, Galassi M, Weerakul S, Pongpirul K. Intra-articular tranexamic acid mitigates blood loss and morphine use after total knee arthroplasty. A randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(5):877–881. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jules-Elysee KM, Tseng A, Sculco TP, et al. Comparison of topical and intravenous tranexamic acid for total knee replacement: a randomized double-blinded controlled study of effects on tranexamic acid levels and thrombogenic and inflammatory marker levels. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(23):2120–2128. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang YM, Yang B, Sun XD, Zhang Z. Combined intravenous and intra-articular tranexamic acid administration in total knee arthroplasty for preventing blood loss and hyperfibrinolysis: a randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(7):e14458. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George J, Eachempati KK, Subramanyam KN, Gurava Reddy AV. The comparative efficacy and safety of topical and intravenous tranexamic acid for reducing perioperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty - a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Knee. 2018;25(1):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed S, Ahmed A, Ahmad S, Atiq-uz-Zaman, Javed S, Aziz A. Blood loss after intraarticular and intravenous tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68(10):1434–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei W, Dang S, Duan D, Wei L. Comparison of intravenous and topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):191–195. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2122-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramanyam KN, Khanchandani P, Tulajaprasad PV, Jaipuria J, Mundargi AV. Efficacy and safety of intra-articular versus intravenous tranexamic acid in reducing perioperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized double-blind equivalence trial. Bone Joint J. 2018;100B(2):152–160. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B2.BJJ-2017-0907.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdel MP, Chalmers BP, Taunton MJ, et al. Intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: both effective in a randomized clinical trial of 640 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(12):1023–1029. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López-Hualda Á, Dauder-Gallego C, Ferreño-Márquez D, Martínez-Martín J. Efficacy and safety of topical tranexamic acid in knee arthroplasty. Med Clin (Barc). 2018;151(11):431–434. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacko M, Cellar R, Schreierova D, Vasko G. Comparison of intravenous and intra-articular tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss in primary total knee replacement. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi. 2017;28(2):64–71. doi: 10.5606/ehc.2017.54914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Wang Q, Zhang X, Wang Q. Intra-articular application is more effective than intravenous application of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(11):3385–3389. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stowers MDJ, Aoina J, Vane A, Poutawera V, Hill AG, Munro JT. Tranexamic acid in knee surgery study-a multicentered, randomized, controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(11):3379–3384. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zekcer A, Priori RD, Tieppo C, Silva RSD, Severino NR. Comparative study of topical vs. intravenous tranexamic acid regarding blood loss in total knee arthroplasty. Rev Bras Ortop. 2017;52(5):589–595. doi: 10.1016/j.rbo.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prakash J, Seon JK, Park YJ, Jin C, Song EK. A randomized control trial to evaluate the effectiveness of intravenous, intra-articular and topical wash regimes of tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2017;25(1):1–7. doi: 10.1177/2309499017693529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gross JB. Estimating allowable blood loss: corrected for dilution. Anesthesiology. 1983;58:277–280. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198303000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen JY, Chin PL, Moo IH, et al. Intravenous versus intra-articular tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a double-blinded randomised controlled noninferiority trial. Knee. 2016;23(1):152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated 2019). Cochrane, 2019. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed 16 Mar 2020.

- 31.Oremus M, Wolfson C, Perrault A, Demers L, Momoli F, Moride Y. Interrater reliability of the modified Jadad quality scale for systematic reviews of Alzheimer’s disease drug trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2001;12(3):232–236. doi: 10.1159/000051263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maniar RN, Singhi T, Patil A, Kumar G, Maniar P, Singh J. Optimizing effectivity of tranexamic acid in bilateral knee arthroplasty - a prospective randomized controlled study. Knee. 2017;24(1):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uğurlu M, Aksekili MA, Çağlar C, Yüksel K, Şahin E, Akyol M. Effect of topical and intravenously applied tranexamic acid compared to control group on bleeding in primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2017;30(2):152–157. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1583270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song EK, Seon JK, Prakash J, Seol YJ, Park YJ, Jin C. Combined administration of IV and topical tranexamic acid is not superior to either individually in primary navigated TKA. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goyal N, Chen DB, Harris IA, Rowden NJ, Kirsh G, MacDessi SJ. Intravenous vs intra-articular tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind trial. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(1):28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.May JH, Rieser GR, Williams CG, Markert RJ, Bauman RD, Lawless MW. The assessment of blood loss during total knee arthroplasty when comparing intravenous vs intracapsular administration of tranexamic acid. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(11):2452–2457. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drosos GI, Ververidis A, Valkanis C, et al. A randomized comparative study of topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid administration in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) total knee replacement. J Orthop. 2016;13(3):127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aggarwal AK, Singh N, Sudesh P. Topical vs intravenous tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss after bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a prospective study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(7):1442–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tzatzairis TK, Drosos GI, Kotsios SE, Ververidis AN, Vogiatzaki TD, Kazakos KI. Intravenous vs topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty without tourniquet application: a randomized controlled study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(11):2465–2470. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinsornsak P, Rojanavijitkul S, Chumchuen S. Peri-articular tranexamic acid injection in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:313. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1176-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keyhani S, Esmailiejah AA, Abbasian MR, Safdari F. Which route of tranexamic acid administration is more effective to reduce blood loss following total knee arthroplasty? Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2016;4(1):65–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aguilera X, Martínez-Zapata MJ, Hinarejos P, et al. Topical and intravenous tranexamic acid reduce blood loss compared to routine hemostasis in total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(7):1017–1025. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Digas G, Koutsogiannis I, Meletiadis G, Antonopoulou E, Karamoulas V, Bikos C. Intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid reduce blood loss in cemented total knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(7):1181–1188. doi: 10.1007/s00590-015-1664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Öztaş S, Öztürk A, Akalin Y, et al. The effect of local and systemic application of tranexamic acid on the amount of blood loss and allogeneic blood transfusion after total knee replacement. Acta Orthop Belg. 2015;81(4):698–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1937–1944. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel JN, Spanyer JM, Smith LS, Huang J, Yakkanti MR, Malkani AL. Comparison of intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(8):1528–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarzaeem MM, Razi M, Kazemian G, Moghaddam ME, Rasi AM, Karimi M. Comparing efficacy of three methods of tranexamic acid administration in reducing hemoglobin drop following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(8):1521–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soni A, Saini R, Gulati A, et al. Comparison between intravenous and intra-articular regimens of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss during total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(8):1525–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seo JG, Moon YW, Park SH, Kim SM, Ko KR. The comparative efficacies of intra-articular and IV tranexamic acid for reducing blood loss during total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(8):1869–1874. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maniar RN, Kumar G, Singhi T, Nayak RM, Maniar PR. Most effective regimen of tranexamic acid in knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled study in 240 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(9):2605–2612. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2310-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang S, Xie J, Cao G, Lei Y, Huang Q, Pei F. Six-dose intravenous tranexamic acid regimen further inhibits postoperative fibrinolysis and reduces hidden blood loss following total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2019. 10.1055/s-0039-1694768. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Chen Y, Chen Z, Cui S, Li Z, Yuan Z. Topical versus systemic tranexamic acid after total knee and hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(41):4656. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCormack PL. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in the treatment of hyperfibrinolysis. Drugs. 2012;72(5):585–617. doi: 10.2165/11209070-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie J, Hu Q, Huang Q, Ma J, Lei Y, Pei F. Comparison of intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty: an updated meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2017;153:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu Y, Shi Z, Han B, et al. Comparing efficacy and safety of 2 methods of tranexamic acid administration in reducing blood loss following total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(50):5583. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tzatzairis T, Drosos GI, Vogiatzaki T, Tilkeridis K, Ververidis A, Kazakos K. Multiple intravenous tranexamic acid doses in total knee arthroplasty without tourniquet: a randomized controlled study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2019;139(6):859–868. doi: 10.1007/s00402-019-03173-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lei YT, Xie JW, Huang Q, Huang W, Pei FX. The antifibrinolytic and anti-inflammatory effects of a high initial-dose tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Int Orthop. 2020;44(3):477–486. doi: 10.1007/s00264-019-04469-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tammachote N, Raphiphan R, Kanitnate S. High-dose (3 g) topical tranexamic acid has higher potency in reducing blood loss after total knee arthroplasty compared with low dose (500 mg): a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2019;29(8):1729–1735. doi: 10.1007/s00590-019-02515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We state that the data will not be shared because all the raw data are present in the figures included in the article.