Abstract

Background

Host genetic factors such as single nucleotide variations may play a crucial role in the onset and progression of HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). However, the underlying genomic copy number variations (CNVs) involved in the pathology are currently unclear.

Methods

We genotyped two cohorts with 389 HBV-related ACLF patients and 391 asymptomatic HBV carriers (AsCs), and then carried out CNV-based global burden analysis and a genome-wide association study (GWAS).

Results

For 1874 rare CNVs, HBV-related ACLF patients exhibited a high burden of deletion segments with a size of 100–200 kb (P value = 0.04), and the related genes were significantly enriched in leukocyte transendothelial migration pathway (P value = 4.68 × 10–3). For 352 common CNVs, GWAS predicted 17 significant association signals, and the peak one was a duplication segment located on 1p36.13 (~ 38 Kb, P value = 1.99 × 10–4, OR = 2.66). The associated CNVs resulted in more copy number of pro-inflammatory genes (MST1L, DEFB, and HCG4B) in HBV-related ACLF patients than in AsC controls.

Conclusions

Our results suggested that the impact of host CNV on HBV-related ACLF may be through decreasing natural immunity and enhancing host inflammatory response during HBV infection. The findings highlighted the potential importance of gene dosage on excessive hepatic inflammation of this disease.

Keywords: Copy number variations, HBV-related ACLF, GWAS, HBV-ACLF, Acute-on-chronic liver failure

Background

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) infection is regarded as a global health issue. The global chronic HBV infection rate in 2015 was estimated at 3.5% involving 257 million people, of which 15–25% died of HBV-related cirrhosis or liver cancer [1]. Caused by severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B (CHB), HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a severe life-threatening disease that exhibits a high 28-day mortality rate of more than 15% [2]. Several risk factors have been suggested to be involved in this common complex disease, including hereditary factors, host characteristics, viral factors, and vigorous immune responses [3–5]. However, the pathological processes are still poorly understood.

Host genetic factors likely play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of HBV-related ACLF. Our group has recently performed a SNP-based genome-wide association study (GWAS) of this disease, and identified a highly associated variant rs3129859*C [6]. The related single nucleotide variation is located in human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR region and likely participates in the function of the HLA-II-restricted CD4+ T-cell pathway [6]. Previous results deepen our understanding of HBV-related ACLF and confirm the importance of host genetic factors in the pathogenesis of the disease. In addition to SNPs, copy number variations (CNVs) as another main type of genetic variations also exhibit a high diversity in human population and are associated with many human diseases [7]. For example, susceptible CNVs on chromosome 1p36.33 [8] and 15q13.3 [9] were proved to be highly correlated with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and CNVs on chromosome 5q35.3 [10] may potentially affect HBV infection by integrating the HBV P gene into natural killer cells. However, direct evidences of association between host CNVs and HBV-related ACLF remains unknown.

In this study, we used Affymetrix Genome-wide Human SNP Array 6.0 to identify high-quality CNV genotyping data for HBV-related ACLF in a Chinese population, and then performed a CNV-based GWAS aiming to expand the scope of genetic screening and further study the underlying genetic and molecular mechanism of HBV-related ACLF.

Methods

Participants, CNV detection and quality control

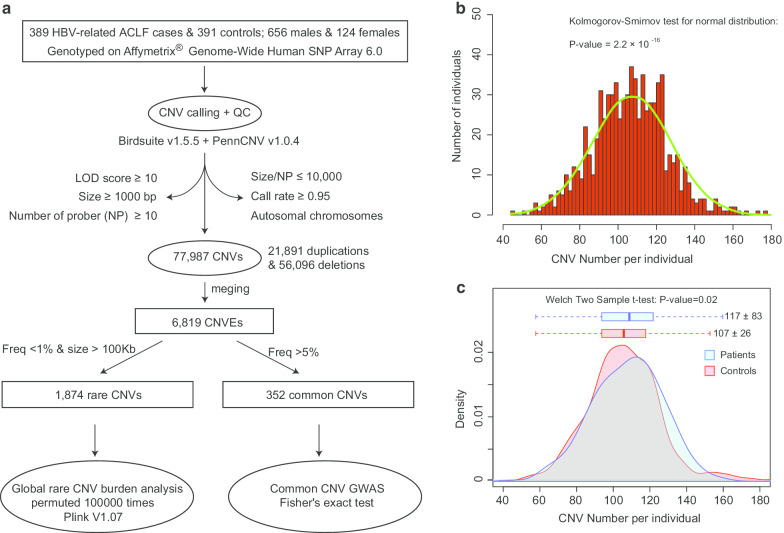

A Chinese population with 780 qualified participants was screened from our previous study (population group of “GWAS stage”), including 389 patients with HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF, cases) and 391 asymptomatic HBV carriers (AsCs, controls) (Additional file 1 and Additional file 2) [6]. The detailed diagnostic criteria for HBV-related ACLF and AsC were also described previously [6]. Standard procedures were conducted to extract the genomic DNAs from leukocytes in peripheral blood. Raw signals of copy number variations (CNVs) were detected using the Affymetrix genome-wide human SNP array 6.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, California, USA), and the CNV genotypes were further determined plate-by-plate using Birdseye (version 1.5.5) under the JCH model (Japanese and Chinese model) [11]. High quality CNV calls should meet five criteria [12]: logarithm of odds (LOD) score ≥ 10, Size ≥ 1000 bp, the number of probes per CNV (NP) ≥ 10, Size/NP ≤ 10,000, and call rate ≥ 0.95. In addition to Birdseye, the software PennCNV (version 1.0.4) [13] was also applied as a complementary algorithm to determine CNVs using the default parameters (Fig. 1a). For the distribution of CNV numbers per sample, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to measure the goodness of fit for normal distribution, which was accomplished by R scripts.

Fig. 1.

Overall analysis methods and genotyping results. a Overall flow chart of genotyping and analysis. Some intermediate results and final results were marked in the figure. The normal distribution test was applied to verify the randomness of the results (b), and the distribution of the CNV number of each individual was very close to normal (P = 2.2 × 10–16). However, the distribution showed significant difference between HBV-related ACLF cases and AsC controls (c), indicating the potential host CNVs difference of the HBV-related ACLF

Determination of common and rare CNVs

A CNV event (CNVE) was clustered from a series of CNV calls that descended from a common ancestral mutation event [12] and had a pair-wise reciprocal overlapping rate of over 50%. Contributing CNV calls of a CNVE may have slightly different breakpoints in the genome. The physical extent of the CNVE was defined as the minimum region covering over 90% of these related CNVs. Meanwhile, the carrier frequency of a CNVE was defined as the proportion of individuals that carried the contributing CNV calls. The common and rare CNVs were CNVEs that have frequency values of > 5% and < 1%, respectively. Additionally, rare CNVs were further filtered by the genome size of > 100 kb. Genes within CNVEs were extracted based on the annotation file from the UCSC Genome Browser (version NCBI36/hg18). All of the above steps were implemented in our in-house Perl scripts.

Global burden and genome-wide association study

Plink-1.07 [14] was used to test whether HBV-related ACLF patients exhibit a greater burden of rare CNVs relative to AsC controls. Statistical significance was established through 10,000 times of permutation. All rare CNVs were divided into three groups according to the genomic size, and each size interval was further divided into three types: duplication, deletion and the combination of them. In addition, two aspects were considered during the detection, including the number of segments per person (RATE) and the proportion of sample with one or more segments (PROP). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Fisher's exact test was conducted to perform genome-wide association analysis for both common duplication and deletion CNVs. The odds ratios (ORs) were calculated from the formula of (nA × ma)/(na × mA), where nA and mA are the total numbers of participants who carry the target CNVs in cases and controls, respectively. The na and ma are the total numbers of participants who exhibit normal condition in the detected region or carry the other types of CNVs in cases and controls, respectively.

Transcriptome analysis and miRNA target prediction

Transcriptome data was collected from NCBI by querying the project number of PRJNA360435, of which 5 ACLF patients (Patient1-T0 to Patient5-T0) and 4 healthy individuals (Control1-T0 to Control4-T0) were selected for further analysis [15]. Raw RNA sequencing data from purified CD14+ monocytes was downloaded, which was sequenced by Illumina NextSeq 500 with a single end of 75 bp. In order to calculate gene expression levels, filtered sequencing data was aligned to the UCSC human gene sets (version NCBI36/hg18) using SOAP2 [16]. Only the unique alignment results were considered to generate reads per Kb transcriptome per million mapped reads (RPKM) values that represented for the relative expression level. The RPKM method eliminates the influence of gene size when comparing expression levels between genes. Based on the expression pattern, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to filter samples exhibiting large distribution bias among samples. To observe the expression pattern of the HLA-A gene in more patients with HBV-related liver failure, we queried the key words in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Profiles database from the NCBI. Expression data of 17 HBV-related ALF samples were obtained under an accession number of GDS4387. The potential miRNA binding sites were predicted using MegaBLAST [17] based on the mature sequences downloaded from miRBase [18]. Results with the highest score, located in 3′UTR (protein coding genes), and mapped 2–8 bp at the beginning of mature miRNA were considered for further analysis [19].

Enrichment of KEGG pathway

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment was conducted in three steps. Firstly, all target genes (TGs) were queried against KEGG orthology (KO) in the database (https://www.kegg.jp) to determine the related pathways. Secondly, a hypergeometric test was used to predict KEGG pathways that were significantly enriched in TGs relative to the genomic background of all genes with KEGG annotations. Thirdly, a Bonferroni correction was calculated to control type I error due to multiple comparisons (threshold: corrected P ≤ 0.05).

Results

CNV detection

For 389 HBV-related ACLF cases and 391 AsC controls, the Birdsuite and PennCNV algorithms yielded 77,987 CNVs (21,891 duplications and 56,096 deletions) in total with a median size of 569,849 bp. All CNV calls were clustered into 6,819 CNVEs, where 4,413 (64.72%) were singletons (Fig. 1a and Additional file 3). The frequency distribution of CNV number per individual (CNPI) was close to the normal distribution (P value = 2.2 × 10–16, Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, the mean values of CNPI were statistically different between the HBV-related ACLF and the AsC group (P value = 0.02, Fig. 1c), which were 117 ± 83 and 106 ± 26 (mean ± SD) respectively. In total, 352 and 1,874 CNVEs were classified as common and rare CNVs (Fig. 1a), respectively, where 331 common CNVs (~ 94%) could overlap (coverage rate > 0.5) with the CNVs from the HapMap database.

Global burden analysis of rare CNVs

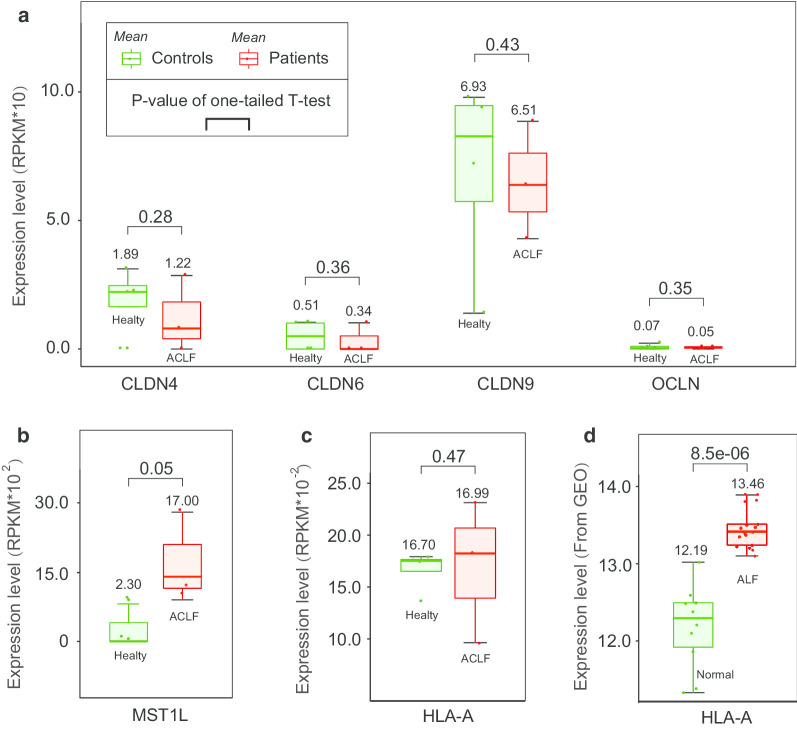

Overall, HBV-related ACLF patients exhibited a significantly higher number of rare CNVs per person than the AsC controls (P value = 0.03; Ratio of RATE: 2.78/0.66), but the proportion of samples containing rare CNVs showed no difference between the two groups (P value = 0.42; ratio of PROP: 0.29/0.28) (Table 1). In detail, HBV-related ACLF patients revealed a high burden of the deletion segments with the size of 100–200 kb, of which the RATE value was more than 4 times than that of AsC controls (P value = 0.04). A total of 1805 genes were contained in the deletion regions (Additional file 4). They are significantly enriched in the leukocyte transendothelial migration pathway (P value = 4.68 × 10–3). Four major sub-functions are affected, including tail retraction, cell motility, docking structure, and transendothelial migration. Twelve key functional nodes (gene products) lost one or more related gene copies, where the most affected node was cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) (Additional file 5) and its mean expression level was relatively lower in HBV-related patients than the healthy controls (Fig. 2a). In other aspects, there was a higher proportion of patients containing the duplication segments with the size of 100–200 kb (P value = 0.02), which covered 172 genes but no KEGG pathway was significantly enriched (Additional file 6).

Table 1.

Results of global rare CNV burden analysis

| Type | Size (Kb) | RATE (case/control) | P value RATEa | PROP (case/control) | P value PROPb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duplications and deletions | 100–200 | 2.05/0.50 | 0.02 | 0.25/0.22 | 0.17 |

| 200–500 | 0.68/0.14 | 0.05 | 0.07/0.10 | 0.93 | |

| > 500 | 0.05/0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02/0.01 | 0.21 | |

| All | 2.78/0.66 | 0.03 | 0.29/0.28 | 0.42 | |

| Deletions | 100–200 | 1.26/0.28 | 0.04 | 0.12/0.13 | 0.61 |

| 200–500 | 0.49/0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05/0.06 | 0.73 | |

| > 500 | 0.03/0 | – | 0.01/0 | – | |

| All | 1.78/0.35 | 0.04 | 0.15/0.16 | 0.68 | |

| Duplications | 100–200 | 0.79/0.23 | 0.13 | 0.16/0.11 | 0.02 |

| 200–500 | 0.19/0.07 | 0.24 | 0.03/0.05 | 0.94 | |

| > 500 | 0.013/0.012 | 0.62 | 0.013/0.012 | 0.62 | |

| All | 0.99/0.31 | 0.14 | 0.18/0.16 | 0.16 |

a,b is the numbers of rare CNV segments per person and the proportion of sample with one or more rare CNV segment, respectively

Fig. 2.

Expression patterns of the potential disease-related genes. Data collection and Expressional calculation was illustrated in the methods part. Low copy number of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) genes may decrease its expressional level (a). More copies of MST1L in HBV-related ACLF likely increase the expressional level (b). The mean expression level of HLA-A was both relatively higher in HBV-related ACLF (c) and HBV-related ALF (d) patients than that of controls

Association study of common CNVs

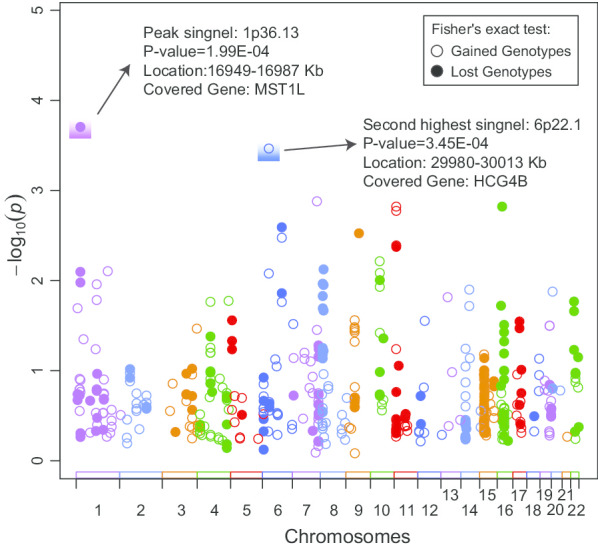

A total of 17 strong disease association signals were detected (Threshold P value: ~ 0.01), including 9 duplications and 8 deletions, respectively (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The peak one was a duplicate CNV on chromosome 1 p36.13 (~ 38 Kb, P value = 1.99E−04), which had the largest OR value (2.66) among all associates and contained the gene MST1L (macrophage stimulating 1 like). The duplicated CNV was enriched in HBV-related ACLF patients and was associated with greater copies of MST1L compared to the AsC controls, which may further increase its expression level. Transcriptome data showed that the relative expression level of MST1L was significantly higher in HBV-related ACLF patients than in healthy controls (P value = 8.20e−4, Fig. 2b).

Fig. 3.

GWAS results of common CNVs for HBV-ACLF. Fisher's exact test was applied to detect all candidate associations for both gained and lost genotypes. The top two highest signals were marked with text description, and the locations were extracted based on the human genome assembly version of NCBI36/hg18

Table 2.

Results of association study of common CNVs

| Chr | Regions | Type | Foreground (case/control) |

Background (case/control) |

Odds ratio (OR) | P values | Genes included* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr1 | 16,894,856–16,929,044 | Duplication | 33/17 | 337/363 | 2.09 | 1.06E−02 | |

| chr1 | 16,949,054–16,987,299 | 48/20 | 307/340 | 2.66 | 1.99E−04 | MST1L | |

| chr6 | 103,854,114–103,868,754 | 79/106 | 301/274 | 1.47 | 1.39E−02 | ||

| chr8 | 7,665,275–7,836,800 | 142/108 | 239/258 | 1.42 | 1.49E−02 | DEFB104A; PRR23D2; SPAG11A; DEFB103A; DEFB105A; DEFB107A; DEFB4A; DEFB106A | |

| chr8 | 7,202,021–7,259,767 | 61/38 | 262/278 | 1.70 | 1.09E−02 | ZNF705G | |

| chr8 | 12,260,380–12,487,426 | 49/28 | 323/345 | 1.87 | 7.56E−03 | FAM86B2; FAM66A | |

| chr9 | 68,055,004–68,312,791 | 32/15 | 231/270 | 2.49 | 3.01E−03 | ||

| chr11 | 4,928,581–4,930,605 | 33/57 | 351/324 | 1.87 | 4.25E−03 | ||

| chr16 | 21,297,471–21,501,135 | 182/147 | 81/114 | 1.74 | 1.52E−03 | NPIPB3 | |

| chr20 | 1,509,580–1,520,451 | Deletion | 303/331 | 63/42 | 1.64 | 1.33E−02 | |

| chr1 | 173,063,028–173,064,310 | 87/120 | 253/230 | 1.52 | 7.92E−03 | ||

| chr1 | 110,034,497–110,047,804 | 89/121 | 216/196 | 1.49 | 1.11E−02 | ||

| chr6 | 29,979,615–30,012,844 | 49/86 | 199/171 | 2.04 | 3.45E−04 | HCG4B | |

| chr6 | 29,945,293–29,989,326 | 43/70 | 121/110 | 1.79 | 8.40E−03 | HCP5B | |

| chr7 | 133,446,174–133,449,737 | 41/71 | 327/296 | 1.91 | 1.33E−03 | ||

| chr10 | 45,905,767–46,573,925 | 129/97 | 254/288 | 1.51 | 6.14E−03 | SYT15; NPY4R; GPRIN2 | |

| chr14 | 40,697,979–40,727,099 | 47/28 | 269/289 | 1.80 | 1.27E−02 |

*Genes include functional genes and lncRNA genes

The second-strongest associate was a deletion CNV on chromosome 6 p22.1 (~ 33 Kb, P value = 3.45e−04), which was enriched in AsC populations and contained a long non-coding RNA gene HCG4B (HLA complex group 4B). HBV-related ACLF patients tended to contain relatively more copies of HCG4B than AsCs. The mean expression level of HLA-A was higher in HLA-A in HBV-related ACLF or ALF patients than that in healthy controls (Fig. 2c, d). More copies of HCG4B likely resulted in greater gene expression of HLA-A, and the positive correlation may be caused by the competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNA) of lncRNA. A total number of 6 potential sponging microRNAs between HCG4B and 3′UTR of HLA-A were predicted, where miR-6823-5p had the largest prediction score (Additional file 7). Except for two top signals, the 6 remaining associations could also contain gene elements, notably a duplicate CNV on chromosome 8 that covered 7 beta defensin genes (Table 2).

Discussion

Aiming to explore the risk CNV in HBV-related ACLF, we performed a global burden analysis and a genome-wide association study of 389 HBV-related ACLF cases and 391 AsC controls. A series of high-quality CNVs were identified using SNP array technology, where over 94% of common CNVs overlapped with the HapMap database, providing a strong foundation for subsequent studies. Our results showed that HBV-related ACLF patients tend to contain more short rare CNVs (100–200 Kb) than AsCs, indicating a CNV burden difference between the two groups of patients. Moreover, a total number of 17 common CNVs were found to be significantly associated with HBV-related ACLF. These findings suggested that host genetic copy number variations likely play an important role in disease onset. Further studies implied that genes within related CNVs may participate in decreasing natural immunity and enhancing host inflammatory response during HBV infections.

Compared to AsC controls, HBV-related ACLF population exhibit a higher burden of rare CNVs with the deletion genotype (Table 1), which resulted in a lower copy number of genes related to the leukocyte transendothelial migration pathway (LTMP). The most affected genes are cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) [20], which are the key genes regulating transendothelial migration and play an important role in the firm adhesion of leukocytes during transmembrane transport [21] (Additional file 5). Transcriptome data revealed that low CAM gene copies may further decrease its expression level (Fig. 2a). As one of the important types of leukocytes, natural killer (NK) cells have been found that its peripheral number, cytotoxicity and killing activity were decreased or downregulated in patients with HBV-related ACLF [20]. NK cells are main cellular responders after HBV infection, and the abnormal status can induce severe liver injury [22, 23]. Evidence has shown that NK cells facilitate the cellular immunity of HBV-related ACLF mainly through perforin and granzymes, or interacting with target cell death receptors [22, 24, 25]. Low gene dosage of CAMs may reduce the migration activity of NK cells and further reduce its cellular immunity.

For association studies, the strongest association signal was a duplication segment with a length of ~ 38 Kb, covering only the MST1L (Macrophage stimulating 1 like) gene (Table 2). MST1L is homologous to macrophage stimulating protein (MSP), and its first 6878 bp sequence was 96.1% identical to MSP [26]. MST1L was once thought a pseudogene of MSP due to the frameshift and termination mutations. However, Yoshimura et al. found that MSP homologous genes could express in HepG2 cells [27], suggesting that MST1L may have transcriptional activity. Transcriptome data from monocytes confirmed this possibility, and revealed a significantly high expression level in HBV-related ACLF patients (P value = 0.05) (Fig. 2b). Li et al. found that some pro-inflammation molecules, such as TNFα, chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 2 (Ccl2), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (Icam1), IFNγ, and interleukin 1 beta (IL1β) [28], were highly expressed in the liver of MSP-treated mice, indicating a possible pro-inflammatory effect of MST1L. Therefore, more copies of the MST1L gene likely increase its expression in HBV-related ACLF patients, and may further enhance the intensity of hepatitis inflammation.

The second top associate was a deletion CNV containing a long non-coding RNA gene of HCG4B, and was enriched in the AsCs population. Transcriptome data indicated that the expression of HCG4B was positively correlated with HLA-A, which may be regulated by competing with the sponging microRNAs. Chen et al. also identified a similar expression relationship (r = 0.45, P value = 1e−3), and predicted the potential sponging microRNAs [29]. In our study, miR-6823-5p was predicted to be the most likely candidate that could both bind to the HCG4B and 3′UTR of HLA-A (Additional file 7). As one of the important components of the major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I), HLA-A can influence the CD8+ T-cell response to infected hepatocytes [30] and the levels of cytokine production that greatly associated with the development of autoimmune inflammation [31]. Low copies of HLA-A and its expression level in AsC controls may alleviate inflammation and reduce the risk of ACLF under unknown situations.

Notably, an associated duplicated segment on 8p23.1, containing a cluster of six β defensin genes (DEFB), also tended to appear in HBV-related ACLF patients. DEFB may act as an effective pro-inflammatory factor and also have a strong antiviral effect [32, 33]. Multiple copies of DEFB can enhance host immune activity. Firstly, DEFB can function as chemokines that modulate immune cell migration properties and the localization of target cells such as monocytes, macrophages, immature dendritic cells (DCs), memory T cells, and mast cells [34–37]. Secondly, DEFB are pro-inflammatory and increase the levels of secreted pro-inflammatory molecules TNF-α and IL-6 levels [38].

Our GWAS results indicated a potential excessive inflammatory response in HBV-related ACLF patients or an alleviated inflammatory response in AsC individuals. An excessive inflammatory response may induce tissue damage and organ failure [39], and the systemic inflammation is a potential major driver of ACLF [40]. The related plasma levels of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10, G-CSF and GM-CSF were higher in ACLF patients (P < 0.05) than that in controls [40], and could be associated with the severity and mortality of ACLF [2]. Other than the intensity of the inflammatory response, inflammation-induced tissue damage also depends on the intrinsic capacity of host organs to endure the inflammatory response (individual difference) [39], which is one of the possible reasons that a certain number of AsC individuals contain the risk CNVs but do not reveal symptoms of ACLF.

There are some limitations in the present study. Firstly, there is still a lack of other cohorts or effective experimental techniques to verify the positive results. Secondly, the transcriptome data is not from the samples of this study, and only reflects gene expression in monocytes. Although it can partly illuminate what HBV-related ACLF patients face, more data in regards to this complex disease should be collected to fully illustrate the true expression pattern among different immune cell subsets. Thirdly, although we have initially observed the possibility of a competitive relationship between HLA-A and HCG4B, the sponging miRNA should be further predicted and validated by further exact methods, perhaps by using small RNA sequencing technology and double luciferase reporter gene experiment. Lastly, it is difficult to assess the true effect of these potential risk CNVs in different populations due to the inherent differences among individuals (such as the capacity of enduring the inflammatory response) or other unknown factors.

Conclusions

The current study observed significant difference in burden of rare CNVs between HBV-related ACLF patients and AsC controls, and also identified a series of disease associated CNVs. The risk CNVs in ACLF patients may further lead to changes of host immunity. Firstly, fewer copies of leukocyte transendothelial migration related genes in patients likely decrease the host cellular immunity. Secondly, copy number variation of genes such as MST1L, DEFB and HCG4B can potentially enhance the inflammatory response of patients during an HBV infection. Our results confirmed that host CNVs can affect the onset of HBV-related ACLF. Future work should foucus on the influence of gene dosage on related pathology, especially abnormal inflammatory response.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Summary characteristics of the participants used in this study.

Additional file 2. Basic information of the participants used in this study.

Additional file 3. Results of merged CNVs predicted by Birdseye and PennCNV.

Additional file 4. Genes locating in the significant lost genomic regions (rare CNVs with the size of 100-200 kb).

Additional file 5. Key deleted genes in leukocyte transendothelial migration pathway.

Additional file 6. Genes locating in the significant gained genomic regions (rare CNVs with the size of 100-200 kb).

Additional file 7. Prediction of potential sponging microRNAs between HCG4B and 3’UTR of HLA-A.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CNV

Copy number variation

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- ACLF

Acute-on-chronic liver failure

- AsC

Asymptomatic HBV carrier

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- CHB

Chronic hepatitis B

- HLA

Human leucocyte antigen

- CNVE

Copy number variation event

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- LOD

Logarithm of odds

- RPKM

Reads per Kb transcriptome per million mapped reads

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- TG

Target genes

- KO

KEGG orthology

- MST1L

Macrophage stimulating 1 like

- MSP

Macrophage stimulating protein

- MHC I

Major histocompatibility complex class I

- DEFB

Beta defensin genes

- DC

Dendritic cells

Authors’ contributions

GD contributed to the conception and design of the study. FS performed bioinformatic analysis and wrote the manuscript. WT revised, edited and provided comments relating to this manuscript. YD, XW, and YG leaded the genotyping and experimental analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81930061, 81900579), the Chinese State Key Project Specialized for Infectious Diseases (2018ZX10723203), the Youth Talent Medical Technology Program of PLA (17QNP010). We also thank the Academy of Medical Sciences Newton International Fellowship (W.T.) and the Youth Talent Program from Army Medical University (F.S., W.T.) for their support. The funder had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The human reference genome sequence was the assembly version of NCBI36/hg18, as downloaded from University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser [ftp://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg18/chromosomes/]. The corresponding gene annotation file of hg18 (the reference gene sets) was also downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser by querying the assembly version of NCBI36/hg18 [http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTables]. Transcriptome data was downloaded from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) profiles database (Accession number: GDS4387).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Southwest Hospital (Chongqing, China) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. Samples of aforementioned participants were obtained during the diagnostic procedure and were deposited at the Hepatitis Biobank of Southwest Hospital after de-identifying process. A doctor who obtained administrative permission to access the clinical patient data and provided the de-identified data to the research team.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Fengming Sun and Wenting Tan have contributed equally to this study

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12920-020-00835-5.

References

- 1.Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1546–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, Durand F, Gustot T, Saliba F, Domenicali M, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1426–U1189. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng G, Zhou G, Zhang R, Zhai Y, Zhao W, Yan Z, Deng C, Yuan X, Xu B, Dong X, et al. Regulatory polymorphisms in the promoter of CXCL10 gene and disease progression in male hepatitis B virus carriers. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(3):716–726. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernsmeier C, Pop OT, Singanayagam A, Triantafyllou E, Patel VC, Weston CJ, Curbishley S, Sadiq F, Vergis N, Khamri W, et al. Patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure have increased numbers of regulatory immune cells expressing the receptor tyrosine kinase MERTK. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):603. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan Z, Tan W, Dan Y, Zhao W, Deng C, Wang Y, Deng G. Estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms and risk of HBV-related acute liver failure in the Chinese population. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan WT, Xia J, Dan YJ, Li MY, Lin SD, Pan XN, Wang HF, Tang YZ, Liu NN, Tan S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies HLA-DR variants conferring risk of HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gut. 2018;67(4):757–766. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girirajan S, Campbell CD, Eichler EE. Human copy number variation and complex genetic disease. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:203–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clifford RJ, Zhang JH, Meerzaman DM, Lyu MS, Hu Y, Cultraro CM, Finney RP, Kelley JM, Efroni S, Greenblum SI, et al. Genetic variations at loci involved in the immune response are risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2010;52(6):2034–2043. doi: 10.1002/hep.23943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao PB, Yang AQ, Wang R, Xia X, Zhai Y, Li YF, Yang F, Cui Y, Xie WM, Liu Y, et al. Germline duplication of SNORA18L5 increases risk for HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma by altering localization of ribosomal proteins and decreasing levels of p53. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):542–556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang Y, Guo WX, Wang JQ, Xu GX, Cheng K, Cao GW, Wu MC, Cheng SQ, Liu SR. Gene copy number variations in the leukocyte genome of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with integrated hepatitis B virus DNA. Oncotarget. 2016;7(7):8006–8018. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korn JM, Kuruvilla FG, McCarroll SA, Wysoker A, Nemesh J, Cawley S, Hubbell E, Veitch J, Collins PJ, Darvishi K, et al. Integrated genotype calling and association analysis of SNPs, common copy number polymorphisms and rare CNVs. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1253–1260. doi: 10.1038/ng.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bochukova EG, Huang N, Keogh J, Henning E, Purmann C, Blaszczyk K, Saeed S, Hamilton-Shield J, Clayton-Smith J, O'Rahilly S, et al. Large, rare chromosomal deletions associated with severe early-onset obesity. Nature. 2010;463(7281):666–670. doi: 10.1038/nature08689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang K, Li MY, Hadley D, Liu R, Glessner J, Grant SFA, Hakonarson H, Bucan M. PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res. 2007;17(11):1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PIW, Daly MJ, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korf H, du Plessis J, van Pelt J, De Groote S, Cassiman D, Verbeke L, Ghesquiere B, Fendt SM, Bird MJ, Talebi A, et al. Inhibition of glutamine synthetase in monocytes from patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure resuscitates their antibacterial and inflammatory capacity. Gut. 2019;68(10):1872–1883. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li RQ, Yu C, Li YR, Lam TW, Yiu SM, Kristiansen K, Wang J. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Ye WC, Zhang YD, Xu YS. High speed BLASTN: an accelerated MegaBLAST search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(16):7762–7768. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D152–D157. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W. Regulation of mRNA Translation and Stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:351–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu FF, Duan XZ, Wan ZH, Zang H, You SL, Yang RC, Liu HL, Li DZ, Li J, Zhang YW, et al. Lower number and decreased function of natural killer cells in hepatitis B virus related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clin Res Hepatol Gas. 2016;40(5):605–613. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller WA. Mechanisms of leukocyte transendothelial migration. Annu Rev Pathol-Mech. 2011;6:323–344. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou Y, Chen T, Han MF, Wang HW, Yan WM, Song G, Wu ZG, Wang XJ, Zhu CL, Luo XP, et al. Increased killing of liver NK cells by fas/fas ligand and NKG2D/NKG2D ligand contributes to hepatocyte necrosis in virus-induced liver failure. J Immunol. 2010;184(1):466–475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z, Zhang SY, Zou ZS, Shi JF, Zhao JJ, Fan R, Qin EQ, Li BS, Li ZW, Xu XS, et al. Hypercytolytic activity of hepatic natural killer cells correlates with liver injury in chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatology. 2011;53(1):73–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.23977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou ZS, Xu DP, Li BS, Xin SJ, Zhang Z, Huang L, Fu JL, Yang YP, Jin L, Zhao JM, et al. Compartmentalization and its implication for peripheral immunologically-competent cells to the liver in patients with HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatol Res. 2009;39(12):1198–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vivier E, Raulet DH, Moretta A, Caligiuri MA, Zitvogel L, Lanier LL, Yokoyama WM, Ugolini S. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science. 2011;331(6013):44. doi: 10.1126/science.1198687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degen SJF, Mcdowell SA, Waltz SE, Gould F, Stuart LA, Carritt B. Structure of the human D1F15S1A locus: a chromosome 1 locus with 97% identity to the chromosome 3 gene coding for hepatocyte growth factor-like protein. DNA Seq. 1998;8(6):409–413. doi: 10.3109/10425179809020903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura T, Yuhki N, Wang MH, Skeel A, Leonard EJ. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of human macrophage stimulating protein (MSP, MST1) confirms MSP as a member of the family of kringle proteins and locates the MSP gene on chromosome 3. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(21):15461–15468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Chanda D, van Gorp PJ, Jeurissen ML, Houben T, Walenbergh SM, Debets J, Oligschlaeger Y, Gijbels MJ, Neumann D, et al. Macrophage stimulating protein enhances hepatic inflammation in a NASH model. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0163843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X, Lu X, Chen J, Wu D, Qiu F, Xiong H, Pan Z, Yang L, Yang B, Xie C, et al. Association of nsv823469 copy number loss with decreased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary function in Chinese. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40060. doi: 10.1038/srep40060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nitschke K, Luxenburger H, Kiraithe MM, Thimme R, Neumann-Haefelin C. CD8+T-cell responses in hepatitis B and C: the (HLA-) A, B, and C of hepatitis B and C. Digest Dis. 2016;34(4):396–409. doi: 10.1159/000444555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dellalibera-Joviliano R, Joviliano EE, Silva JS, Evora PRB. Activation of cytokines corroborate with development of inflammation and autoimmunity in thromboangiitis obliterans patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;170(1):28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holly MK, Diaz K, Smith JG. Defensins in viral infection and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Virol. 2017;4:369–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-101416-041734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hollox EJ. Copy number variation of beta-defensins and relevance to disease. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2008;123(1–4):148–155. doi: 10.1159/000184702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soruri A, Grigat J, Forssmann U, Riggert J, Zwirner J. Beta-defensins chemoattract macrophages and mast cells but not lymphocytes and dendritic cells: CCR6 is not involved. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(9):2474–2486. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang D, Chertov O, Bykovskaia SN. Defensins: linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science. 1999;286(5439):525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chertov O, Michiel DF, Xu L, Wang JM, Tani K, Murphy WJ, Longo DL, Taub DD, Oppenheim JJ. Identification of defensin-1, defensin-2, and CAP37/azurocidin as T-cell chemoattractant proteins released from interleukin-8-stimulated neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(6):2935–2940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohrl J, Yang D, Oppenheim JJ, Hehlgans T. Human beta-defensin 2 and 3 and their mouse orthologs induce chemotaxis through interaction with CCR2. J Immunol. 2010;184(12):6688–6694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meisch JP, Vogel RM, Schlatzer DM, Li XL, Chance MR, Levine AD. Human beta-defensin 3 induces STAT1 phosphorylation, tyrosine phosphatase activity, and cytokine synthesis in T cells. J Leukocyte Biol. 2013;94(3):459–471. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0612300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335:936–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu W, Yan HD, Zhao H, Sun WJ, Yang Q, Sheng JF, Shi Y. Characteristics of systemic inflammation in hepatitis B-precipitated ACLF: differentiate it from No-ACLF. Liver Int. 2018;38(2):248–257. doi: 10.1111/liv.13504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Summary characteristics of the participants used in this study.

Additional file 2. Basic information of the participants used in this study.

Additional file 3. Results of merged CNVs predicted by Birdseye and PennCNV.

Additional file 4. Genes locating in the significant lost genomic regions (rare CNVs with the size of 100-200 kb).

Additional file 5. Key deleted genes in leukocyte transendothelial migration pathway.

Additional file 6. Genes locating in the significant gained genomic regions (rare CNVs with the size of 100-200 kb).

Additional file 7. Prediction of potential sponging microRNAs between HCG4B and 3’UTR of HLA-A.

Data Availability Statement

The human reference genome sequence was the assembly version of NCBI36/hg18, as downloaded from University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser [ftp://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg18/chromosomes/]. The corresponding gene annotation file of hg18 (the reference gene sets) was also downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser by querying the assembly version of NCBI36/hg18 [http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTables]. Transcriptome data was downloaded from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) profiles database (Accession number: GDS4387).