Abstract

Background and Objectives

We explore the internal and external resources that older adults use to negotiate adversity and related to later life. We investigated the experiences older adults had with adversity and explored the factors that promote and protect resilience and the how these factors shaped the process of managing adversity related to aging.

Research Design and Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 64 resilient adults ranging in age from 53 to 94 years of age, with an average of 71. Participants were defined as resilient on the basis of their willingness to identify as such. Grounded Theory coding techniques were applied to identify themes reflecting distinct ways in which participants dealt with what they indicated were the most significant hardships and adversities in their lives.

Results

What emerged from the narratives about resilience and adversity were accounts of expressions of resilience that reflected the importance in having a resilient identity. Three major themes reflecting psychological and behavioral factors were derived from the data: 1. having vital components of resilience, or behaviors and beliefs in place, that encompass resilience as a way of being; 2. a broad but articulate set of strategies that participants actively engaged with to manage adversity, and 3. a set of protective practices used to prevent risk and prevail in the face of hardship.

Discussion and Implications

Findings suggest that dealing with adversity in later life requires the use of substantial internal and external resources in what can characterized as a proactive fashion. The results are presented as an interpretation of the participants’ perceptions of their resilience and the role it plays in self-concept, strategic planning, and proactive practices. Implications for helping to put resilience into everyday practice are considered.

Keywords: Resilience, adversity, identity, proactivity, aging, qualitative methodology

Introduction

As people grow older and move through life they will experience an extensive range of life events. These events vary in type and nature. For some, major life events are characterized as difficult, challenging, or even traumatic while for others these events are opportunities for growth and development. Individuals who manage to navigate adversity and hardships in a manner characterized as flourishing and are often considered resilient (Manning, 2012; Ryff & Singer, 2003). Despite the popularity of resilience as topic of scholarly investigation, relatively little research exits examining resilience from the perspectives of older adults themselves (Wiles, Wild, Kerse, & Allen, 2012). While we have been able to assess, measure, and predict resilience in a manner that quantifies experiences with adversity and hardship, we have done comparatively less work exploring resilience as an experience or way of being from older adults’ perspectives. The research presented in this article explores resilience as older adults, willing to discuss their encounters with adversity and hardship, experienced it. Additionally, this research contributes to the scholarly discourse on resilience and aging, and offers a conceptual framework for understanding resilience in later life that is grounded in the narratives and experiences of older adults. Futhermore, the research presented here offers potential interventions aimed at bolstering resilience for as individuals as they age.

Resilience in the Context of Internal and External Factors

When considering resilience broadly, researchers are attempting to understand and describe the capacities of individuals to navigate adversity in a manner that protects well-being (Manning, 2012; Ryff, 2003; Reich, Zautra, & Hall, 2010), health and life satisfaction (Priscila, Granero, & Giancarlo, 2017). Borrowing from psychology’s tradition of exploring resilience, gerontological scholarship on resilience has reflected an individualistic and micro-analytical perspective (for a comprehensive review of resilience within the field of gerontology see Wild et. al, 2012). As a result, there is an abundance of literature that addresses the individual factors that contribute to resilience. Gerontologists have done less to understand older adults’ experiences of resilience in relation to their environmental, social, and cultural contexts (Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve, Allen, 2012). In addition, while researchers have attempted to understand resilience as it relates to human experience, more is needed to better understand and define resilience from those experiencing hardship and adversity, particularly for older adults (Schetter & Dolbier, 2011). Additionally, resilience can be understood as a dynamic interaction between an individual and their environment (Driessens & Van Regenmortel, 2006; Janssen, Abma, & Van Regenmortel, 2012). Resilience is a complex and dynamic process that is best understood in the context of internal and external factors.

When considering internal factors, researchers have suggested that competence, inner strength, optimism, and flexibility are embedded in individual resilience (Masten, 2009; Luthar et al., 2006; Ryfff, 2003; Wagnild & Collins, 2009). Internal factors of resilience include, at some level, personality traits, emotion regulation, appraisal skills and problem-solving abilities, self-conceptualization and various aspects of positive well-being (Smith, Hayslip, Jr., 2012). Additionally, positive characteristics such as forgiveness, optimism, a sense of purpose, and mastery have been identified as important internal aspects of resilience (Caltabiano & Caltabiano, 2006; Masten & Wright, 209; Zautra, Hall, & Murray, 2010). These and other attributes reflect the vastness of the individual and internal aspects of resilience. A considerable amount of existing research on resilience favors the importance of and inquiry into the intra-individual and inter-individual expressions of resilience (Smith, Hayslip, Jr., 2013; Rutter, 2010). In other words, existing research has contributed to our understanding of individual and microresilience, while research on the process of resilience in relation to contextual and structural factors is comparatively lacking.

Locus of control is also a salient factor in resilience variables for older adults. Researchers indicate an internal sense of control (locus of control) is related to coping mechanisms in older adults such as using problem focused strategies in dealing with depression and medical hospitalization (Hanevold-Bjorklof, Engedal, Selbaek, Bezerra-Maia, Coutinho, & Helvik, 2016; Casten). Other researchers have indicated a high locus of control may reinforce cognitive appraisal that promote self-efficacy and self-esteem in coping strategies (Archer, Kostrezewa, Beninger, Paloma, 2008). Other studies have shown resilience is often cultivated earlier in the lifespan and is often associated with higher self-esteem and internal locus of control (Cazan & Dumitrescu, 2016). Locus of control as well as other internal aspects of resilience mentioned earlier are important in understanding the formation and development of resilience across the lifespan.

External factors may also impact the development and formation of resilience. Bolton, Praetorius, and Smith-Osborne (2016) explored qualitative themes in the dynamic process of overcoming adversity. These researchers indicated external connections such as relational living, family support, social support, and societal responses make a difference in building resilience. Many apects of social support, connectedness, and meaning may affect the process of resilience building, especially when considered with locus of control, positive perspective on life, and grit (Bolton, Praetorius, and Smith-Osborne, 2016).

Resilience is complex. Researchers have endeavored to understand the inter-individual and intra-individual components of resilience as well as how individual resilience interacts with contextual and environmental factors. Despite these attempts at examining the complexity and multidimensionality of resilience in later life, researchers have spent less time empirically understanding resilience from the perspectives of older adults themselves. What is resilient aging, what role does having a resilient identity play in being resilient, what protective factors do older adults deem important in successfully being able to manage and navigate adversity, what strategies do they employ to prevent risk and plan for adversity, what enhancement strategies for resilience do they find most attractive, and what is an ideal environment that enables them to maximize opportunities for resilience? The research presented here further contributes to the understanding of resilience as human experience and elucidates this understanding from older adults’ experiences of adversity.

Resilience as Praxis

Regardless of impairments, general losses, declines, and diminishments that are often times associated with growing older, individuals continue to have to capacity for resilience as they age (Janssen, Abma, & Van Regenmortel, 2012; cite). Existing research indicates that in the face of grave adversity, older adults are willing and able to prevail (Ryff & Singer, 2003; Ryff, 2014). If one holds a dynamic and fluid view of resilience, supposing that, at some level, all older adults have the capacity for resilience as they age, then a logical question becomes how do we promote and enhance resilience throughout the life course? What do interventions and resilience-enhancing tools that bolster people’s ability to be resilient look like? How do you translate resilience into community-based intervention programs or into policy? Can you teach older adults to be more resilient? The answers to these questions will depend on the perspectives that researchers and policy makers hold on resilience. As Diehl, Chui, Hay, Lumley, Grühn, and Labouvie-Vief (2014) explained, if resilience is conceptualized as relatively fixed, constant, and a non-modifiable feature of person, then efforts for enhancing resilience would likely focus on amending an older adult’s environment to enhance resilience. Conversely, if resilience is conceptualized as a process, then it is plausible that a person’s resilience can be enhanced in ways that benefit an individual in various domains of their life (i.e., therapeutic interventions, a resilience check-list, learned adaptive coping strategies, or mindfulness training).

It is important for qualitative researchers to state their biases regarding resilience. We theorize resilience as a process of human and socio-cultural development and capacity building over the life course, and assume that individuals have the ability to enhance and bolster their resilience. Social connection is a vital aspect of resilience-as-process. Ultimately, individuals strive to feel connected, feel that they belong, and feel valued. Strong and supportive social connections are vital at all points in the life course. Social connections support healthy aging, vitality, and foster a sense of wellbeing. Perhaps efforts focused at enhancing resilience, translating resilience into intervention-based programs or considering the policy implications of resilience need to promote stronger social connections while fostering strength and the ability to bounce back. While existing research has indicated that various forms of training and enhancement of life skills strategies has positive effects on well-being (Sancassiani, Pintus, Holte, Paulus, Moro, Cossu, Angermyer, Carta, Lindert, 2015), little data exists demonstrating the effectiveness of resilience building programs and interventions for older adults. The research presented in this article illuminates a resilience-as-process framework that emerged from the experiences of the older adults in this study. Resilience interventions and translations into policy are considered.

Using a qualitative design - specifically grounded theory, we explore how internal and external resources and their related relevance for older adults shaped experiences with adversity and hardship. We investigated the experiences older adults had with adversity and explored the most salient resources that promote and protect resilience. In this investigation of resilience, we were specifically interested in how they managed adversity over the life course. What emerged from the narratives about resilience and adversity were accounts of expressions of resilience that reflected the importance in having a resilient identity. This identity was cultivated through the use of management strategies and protective practices that shaped individuals’ ability to be resilient while negotiating risk when faced with adversity or distressing life events. Findings related to this key theme and their implications are presented and discussed in the remaining sections.

Methods

Design and Sample

In this qualitative study, we employed a grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) to explore, understand, and theorize how older adults experienced and navigated hardship and adversity. Data were collected using a one-on-one interview format and were conducted by one researcher throughout study. Findings from the data emerged suggesting that the older adults were intentional and methodical in how they managed hardship and adversity while simultaneously negotiating risk.

Participants were not randomly selected or predetermined during the initial planning stages of the project; rather older adults were selected to participate in this study based on the first-hand experience with the phenomenon of interest – having experienced hardship and adversity at some point in their lives. In order to recruit participants, a sample was drawn from a participant registry connected to a Center for Aging in the southeastern part of the United States in addition to hanging flyers in senior centers and community centers in the community. Individuals from the registry were contacted via email to see if they were interested in participating. Recruitment flyers were placed in senior and community centers and participants contacted the researchers if they were interested in participating in the study. Each participant that enrolled in the study completed the interview. Furthermore, researchers excluded participants with cognitive limitation as determined with the ability to hold a cogent conversation via phone about the study during the intial call to set up the interview. As a result, participants were mainly healthy, cognitively intact and community dwelling.

This study used a theoretical sampling approach, common in qualitative design (Strauss & Corbin, 1990; Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The participants in our study illustrated a convenience sample of older adults ages 53 to 94 with an average age of 71, who were willing and able to discuss their experiences of adversity and hardship. Participants were sought based on a variety of settings and living arrangements, the participants resided in the Southeastern region of the United States and were community dwelling. The sample size was 64, of those 64 individuals 21 were black and 43 were white. There were 34 women and 30 men. Additionally, there was considerable variation regarding socio-economic status and educational attainment. The annual household income for participants ranged from under $20,000 to over $150,000 and the range of education attainment ranged from no high school degree to doctoral and postgraduate education and training with the majority of participants having a college degree. Initial interviews lasted from one to three hours. Participants were asked a series of questions about how they defined resilience, what were recent and earlier experiences with adversity and hardships, and what were the internal and external resources used in dealing with these experiences of overcoming.

A grounded theory approach was employed to analyze the narrative data from interviews. This approach examines the contents of the data for the common themes or patterns, which evolve from the narrative (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005; Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The themes and patterns were either observations or a concept that are repeatedly reported by informants. Grounded theory is an appropriate qualitative method for this projectWe arrived at an emergent theory, conceptualizing the relationship between resilience and the negotiation of hardship and adversity. This theory is discussed below in the findings section.

Strauss and Corbin (1990) state “the first step in theory building is conceptualizing,” indicating that open coding is that part of the analysis describing the phenomenon found within the text (p. 2). To maintain a level of clarity and organization, we looked for causal references and attempted to fit things into a basic frame of generic relationships (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Once the categories were related, we then began to group the related categories together into larger themes. This process is known as selective coding, where codes from the axial stage are refined and further developed.

Through constant-comparison analysis, interpretations, and syntheses of the emergent themes, as well as taking into consideration the existing literature on resilience and aging, four main findings emerged. These are presented below. Emergent findings were then categorized into larger concepts or major themes from the data, reflecting the substantive nature of resilience and the implication it has for experience resilience as a way of being. These analyses incorporated how participants experienced resilience in a manner that allowed us as the researchers to arrive at an emergent theory of resilience in later life. This conceptual framework of resilience as a way of being is the primary finding. Additionally, we present secondary findings that investigate management strategies and protective practices associated with resilience. We discuss how these findings are also part of the resilience process for the participants in this study.

Results

The findings presented here offer insight into how a specific group of older adults experience hardship and adversity, and as a result how they experience and come to understand resilience as a way of being. In particular, analysis of these data reveals the importance of having a resilient identity as a way of informing how participants made meaning of adversity while achieving comfort with vulnerability. Furthermore, findings illustrate how participants described resilience as a process. Resilience in older ages is the ability to stand up to adversity and to ‘bounce back’ or return to a state of equilibrium following adverse episode. The data presented here reflects a process of resilience that often accumulates over time. Examples from participant narratives illustrate processes as well as aspects of personality. Traits and process are not mutually exclusive.

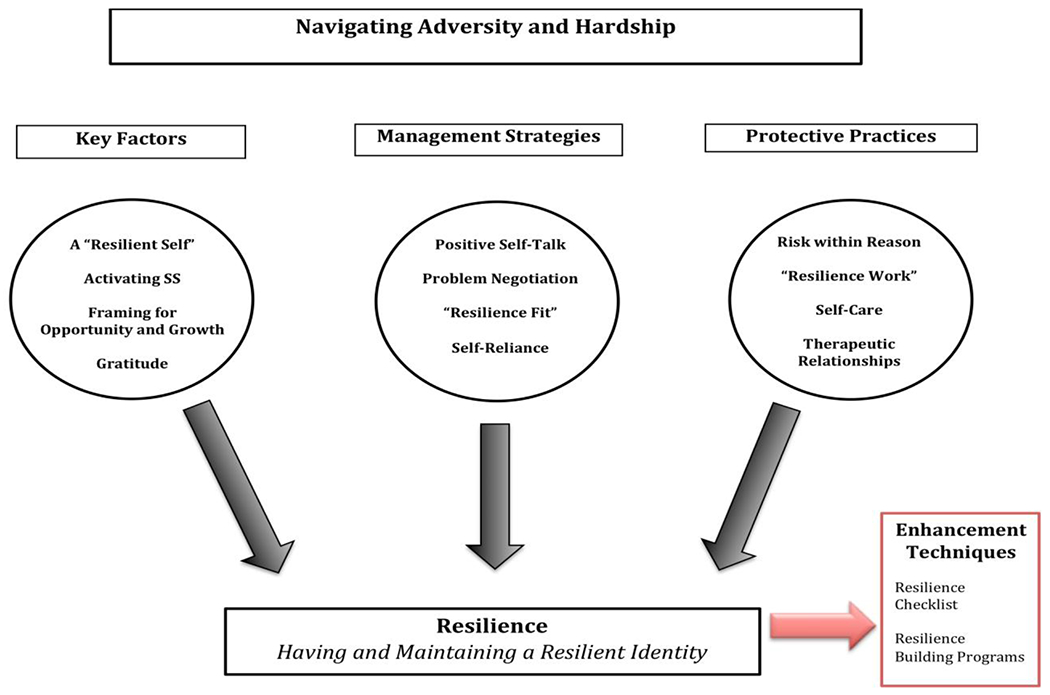

The participants whose data were analyzed here illustrate three overarching themes in their narratives as they described the adversities, hardships, challenges and even opportunities associated with growing older. Overall, the key themes that emerged from the data were: 1. having vital components of resilience, or behaviors and beliefs in place, that encompass resilience as a way of being; 2. a broad but articulate set of strategies that participants actively engaged with to manage adversity, and 3. a set of protective practices used to prevent risk and prevail in the face of hardship. These constructs and their emergent sub-themes are discussed below; a conceptual map is offered to further illustrate these findings.

Vital Components of Resilience

Overall, participants articulated key factors that were important and vital components to how they understood themselves as resilient. Collectively, these factors, behaviors, and beliefs comprise resilience has way of being for participants. Additionally, interviews with participants suggest that resilience as an experience is effable and that participants can articulate what it means to be resilient as they age. Within the sphere of key factors that make up resilience, several features of resilience emerged. There were key sub-themes that emerged such as having a strong resilience identity (or a resilient self), activating social support, reframing hardship, practicing gratitude, and recognizing the ordinary. A major theme in these data is the importance of having a strong resilience identity or the participants’ conceptions of being resilient. This is what I refer to as the resilient self. The majority of participants discussed being resilient rather than having resilience. The concept of a resilient identity refers to the inner experience of a person’s ability to overcome adversity and hardship and the process of bouncing back. A resilient identity is the outcome of the processes through which one identifies their abilities to reframe problems while recognizing the possibilities for growth and expansion that managing hardships can offer.

For many, this identity was formed in late childhood or early adolescence and moved with them over the life course. For example, one participant discusses his resilience as a lifelong identity that formed early in his childhood. He explains the formation of this identity as he recounts an adversity from his childhood.

P: I learned to deal with hate and hardship early on. I grew up black in the South. I remember once being pulled out of a diner and into an alley by some kids my age. The roughed me up and I went home with the proof on my face. I remember sitting down with my mom and she helped me understand that I was a strong and that I could get through this. She taught me how to deal with the fact that there’d be some harsh realities in life. She told me that I was strong and I believed her. She taught to be resilient and that’s always been part of who I am.

In addition to having a strong resilience identity, participants were adamant and intentional about the importance of their social support networks as a vital component of how they were resilient and how this identity was maintained. In other words, participants stressed the important of engaging in connections and activating social support networks and resources. This process of engagement and activation was strategically based on the adversity or hardship, and thus I refer to the activation of social support as a vital component of resilience for participants. For many participants, the ability to access social supports in the form of family, friends, community outlets, or any other types of social interactions or engagement was formulaic in relation to adversity or hardship. In other words, participants were clear and strategic about how their social support networks worked for them and which facets of the network were engaged at what time in the process of dealing with adversity. Furthermore, participants stressed the importance of activating aspects of their social support system according to the type of hardship or adversity they encountered. Activating the systems suggests that there is perhaps something unique happening within the convoy of social support model and this can potentially advance the understanding of how people manage and engage with social support outlets.

When asked about their experiences with adversity and hardship, participants expressed a relationship with adversity that was marked by the ability to reframe the experience and conceptualize hardship as a potential for possibility and growth. Accounts of adversity and negotiations of hardship reflected the participants’ needs and desires to reframe the problematic nature of events in their lives into opportunities for expansion and development. The framing of hardship was an important element in how participants understood themselves as resilient with the ability to frame for opportunity, growth, learning and personal expansion. In addition to framing for the positive, participants also expressed a deep commitment to being grateful for their trials with adversity. Gratitude as prominent theme across interviews about resilience; participants described the importance of gratitude as a vital component of their resilience. Participants also articulated examples of resilience and recognized themselves as resilient in the ordinariness of life and loss. In other words, experiences with adversity were rarely described as gallant experiences of overcoming and managing hardship, but rather participants explained that resilience occurred in the everyday lived experience. One participant describes her ordinariness:

P: I am resilient but I am not a superhero. I guess for me it’s about being able to withstand and overcome all the obstacles in life and to keep doing this, every day, moving along and forward. It’s ordinary living, part of just what life entails. It’s not really magical.

Participants in this study identify several key factors that collectively evidenced vital components of resilience. Themes emerged from the data to support and illustrate the larger finding that for the participants having a resilient identity was important to how they managed adversity and hardship throughout their lives. A resilient identity is formed and maintained with the presence of these vital components. In addition to key factors, participants identified specific management strategies and protective practices that were present their experiences of resilience.

Management Strategies Associated with Resilience

Participants recognized several key management strategies as important to their experiences of being resilient. The strategies were commonly proactive in nature and discussed in the context of planning for adversity and hardship. The process of planning for adversity reflected how participants used previous hardships as catalysts for implementing their management strategies and negotiating future opportunities for resilience. Several strategies emerged from these data: the important of positive self-talk, problem reframing, implementing a resilience fit, being comfortable with vulnerability, and relying on the accumulation of resilience.

When asked about the strategies used to manage resilience, participants described the importance of self-talk or the use of positive and regular dialogue with self. Participants engaged in self-talk as a management strategy by talking themselves through adversities. In other words, participants would remind themselves of their ability to be resilient in the face of adversity. This practice was intentional and the examples of the dialogue where affirming and encouraging. Another strategy that emerged from the data was problem reframing. When asking participants how the managed and negotiated hardships, the treatment of problems was significant. Participants were explicit about the importance of confronting, reframing, and solving their problems as all part of how the manage hardships. This process was intentional and for many participants calculated.

P: I have two choices. I can deal with what life has thrown at me or I can bury my head in the sand. I choose the first option. When crisis strikes I get real quiet and I think. I think hard about what the situation is and how exactly I’m going to tackle it. I try hard to leave emotion out of it at first and take a good long look at what exactly is going on.

In addition to discussing their conceptualization and confrontation of problems, participants also discussed the importance of having all the variables for resilience in place, or having a resilience fit. The resilience fit refers to having a fine-tuned formula from years of practice with navigating hardships in life. For many participants, resilience fit encompassed elements of social support (which people and how much), physical well-being, mental health supports, and self-compassion they needed and in what balance to feel they are being resilient. Furthermore, participants discussed the importance of environmental factors such as socio-economic status, access to healthcare and financial resources as part of the fit. Vulnerability was another key strategy for managing hardship. Participants expressed that being vulnerable was important and was required for their ability to be resilient. Participants detailed their experiences with vulnerability in a variety of contexts. For some, vulnerability was evidenced in relationships and for others it was experienced in the context of physical loss and decline associated with aging. Participants refrained from dichotomizing their experiences with vulnerability and resilience, recognizing that they could not be resilient without being vulnerable. Participants demonstrated a comfortable relationship with vulnerability and describe moments of vulnerability as necessary to their resilience.

Participants reflected on their experiences of resilience as cumulative processes and experiences. Accumulated resilience served as a useful tool in being able to manage adversity and hardship. In other words, using the skills and experiences gleaned from earlier experiences with hardship and adversity as tools for being able to handle hardship and bounce back in current situations allowed them to engage their resilient selves. Detailing how the addition of hardships as they grew older (or accumulated resilience) provided self-confidence and self-trust when they were confronted with managing more recent challenges. Participant narratives did not reflect an association between number of previous adverse events and resilience.

Protective Practices as a Way to Negotiate Risk

Risk and resilience have a symbiotic relationship; it is difficult to be resilience without experiencing risk or adversity. Participants discussed their conceptualizations and handling of risk; for most the treatment of risk was planned, purposeful, and intentional. Several sub-themes emerged from the data as participants were asked about the practices that were in place to deal with and manage planned and unplanned risk.

Participants discussed their thought processes for dealing with risk, and recognized that being resilient meant having to deal with adversity. For several participants, risk was described as engaging in behavior that could potentially result in fall or event that might compromise their ability to be independent. Negotiating risk was a process and participants described some risk as being worthy of taking while other risks were not worth it. In other words, participants expressed taking risks within reason. Participants reflected on the riskiness of life and how those risks needed to be weighed. One participant felt strongly about taking risks but within reason, particularly as she aged.

P: I take chances for my age, and I know that I put myself in harm’s way but it’s important that I keep moving and moving forward despite the fact that I slow and change as I grow older. I know that being out in the garden or on top of a ladder washing windows may result in a fall or broken bones and that could be a major adversity for me, but I’m willing to take the risk. Checking out seems riskier to me.

Another important protective practice involved a degree or physical, emotional, and or spiritual work related to the handling of risk. Participants described the importance of doing their resilience work. In other words, participants articulated that being resilient wasn’t always easy, and similar to physical exercise, being resilient demanded a commitment to doing their “resilience work” or doing what they identified to be good for them while engaging in behaviors that helped them navigate and recover from hardship. Additionally, participants discussed openly the need and commitment for self-care. For some this was meditation, exercise, or regular time in solitude while unplugging. For others, this meant time with people they cared about, adequate sleep, small celebrations, or appointments with their therapists. Overall, participants detailed the importance of managing in self-care, kindness, and preservation, or being kind to oneself and practicing self-care as crucial to being able to deal with hardship and adversity. Another important aspect involved in the management of risk was the importance of mental health care. Having therapeutic relationships in place was an emergent theme prevalent in many of the narratives. The importance of seeking out and engaging in therapeutic relationships with clinicians or in some cases chaplains was vital across the interviews. Participants recognized that resilience was contextual and relational and their mental health work helped them in their experiences with hardship. One participant explained the importance of mental health care.

P: I can tell you about hardship. Substance abuse and depression don’t discriminate. Despite the fact that I’m in this place of transition, I still consider myself to be resilient. I’m learning with, the help of my therapist and caseworker, how to overcome some of these obstacles. I’m learning the importance of taking care of myself. It’s hard and as a man I’m conditioned to not practice this, but I’m to the point now where I know I have to take care of me. I’m learning my triggers and places of risk and am trying to be more proactive with my health. I can’t expect others to deal with my emotional health if I’m not going to.”

A Conceptual Framework of Resilience

We conclude that older adults in this study articulated a process of resilience resulting in a way of being that allowed them to navigate and negotiate adversity, hardship, and risk. This process involved vital components of resilience, management strategies or the negotiation of adversity, and protective practice that facilitated the treatment of risk – all explained in the previous section. Collectively, these factors led to the development and maintenance of a resilient identity for participants in this study. This theorizing of resilience is captured in the conceptual framework presented here.

Conclusion

Experiencing adversity and hardship is inevitable and this is particularly true, as we grow older. Rather than barriers to optimal aging, adversities and hardships in all their variation can serve as opportunities for growth, development, and personal expansion (Resnick, Gwyther, & Roberto, 2010). In this article, we suggest that as people move through their lives they are constantly and continually navigating adversity and hardship, negotiating risk, and as a result for many of the participants in this study, cultivating a resilient identity. Additionally, we identified key components of resilience for participants in this study and describe salient management strategies and protective practices that older adults use to help safeguard and promote their resilience. Recognizing that the type of adversity and the subsequent process of resilience differed for each participant, the findings reported here illustrate salient themes related to how participants manage and make sense of hardship.

For participants in this study, resilience was portrayed as a process involving at some level involved bouncing back from adversity, moving forward despite perceived barriers, and reframing for possibility and growth. These experiences with hardship illustrate a process that is cumulative and suggests that resilience may increase following optimally managing adverse events at different stages of the life course (Browne-Yung, Walker & Luszcz, 2015; Luthar, Cicchetti & Becker, 2000; Tuck & Anderson, 2014). In many ways, the work presented here supports and expands upon this construct. Not only did participants engage in resilience thinking, but they intentionally used their management strategies and protective practices in a proactive manner. Intentionality coupled with identity resulted in an enhanced sense of resilience and a result fit approach that enabled participants to endure and grow from the adversities in their lives. The strategic use of management strategies and protective practices allows older adults to navigate life’s challenges and hardships using a positive lens. The participants’ resiliency as a process helped to determine that they were able to glean the positive from negative events and turn a problem into an opportunity for growth, expansion, and personal transformation. Collectively, these proactive behaviors and adaptive orientations associated with how participants managed stress and adversity in later life is consistent with the existing data on proactivity and successful aging (Kahana, Kahana, & Lee, 2014). Having and maintaining a resilient identity in a proactive fashion is important throughout the life course and potentially more important later in life.

Although this contributes to the existing knowledge about how resilience is negotiated and managed from a qualitatively “lived” experience by people as they age, it does have its limitations. Firstly, the sample was drawn from a participant registry connected to a center for aging in the southeastern part of the United States. Hence, it may reflect experiences and narratives of people accustomed to being researched and therefore my not be representative of the heterogeneity of the older adult population. Furthermore, the researchers excluded participants with cognitive limitation. As a result, participants were mainly healthy, cognitively intact and community dwelling.

Despite these limitations, this study has important theoretical and practical implications. At a theoretical level, this study elucidates the potential value of forming, having and maintaining a resilient identity. Furthermore, findings illustrate that having resilience in the form of internal and external resources can bolster one’s ability to be resilient against deleterious events often associated with later life. Also, at a theoretical level, our findings suggest that because resilience involves certain ways of being, strategic processes and the employment of various management strategies. It is therefore plausible to consider that resilience is a learnt process as well as an achievable identity.

Recognizing that resilience is a learnable behavior (Mealer, Jones, Newman, McFann, 2012), it is likely that interventions can be created to aid in older adults in their ability to bolster resilience. Interventions that provide training in resilience enhancement techniques or utilize a resilience-building curriculum grounded in research and theory have the potential to aid older adults in optimally navigating and negotiating adversity. Additionally, future work needs to explore ways that we can support the development of a resilient identity.

Resilience as a way of being included active management strategies (rather than innate hardiness) as well as a set of protective practices used to prevent risk, especially as hardship was imminent or already occurring. The process of developing a resilient identity does not occur in a vacuum, and consistent with life course theory, contextual and environmental factors are always at play in this process. Our findings suggest that we need to begin to identify ways to help older adults bolster their resilience resources. Policy makers need to recognize the potential of promoting resilience as a way of allowing older people to cope better with difficulties in later life. Policy redocumentations in the form of potential solutions to promote resilience can consider factors associated with resilience. Such policy recommendations could include general measures to bring about improved health and wellness, opportunities to engage in a healthy lifestyle, and outlets for social engagement and integration (i.e., volunteering programs, fitness clubs in communities of faith, or late life learning opportunities). Regardless of background there is hope resilience may play a part in positive aging, and it also does not have to remain stagnant through hardship and struggle. More research is needed to explore the various pathways to resilience, to understand worldviews of older adult, to determine the ways we create and practice resilience, and mine strategies for people to strengthen the self. Additionally, future research should investigate ways by which people can create reserves of resilience and tap into existing pools or internal and external resources. How can we encourage people to access to social support mechanisms or mental health resources, and create opportunities for individuals to enhance their resilience?

Figure 1:

A Conceptual Framework of Resilience

Contributor Information

Lydia K. Manning, College of Graduate Studies and the Division of Human Services at Concordia University-Chicago.

Lauren Bouchard, Concordia University-Chicago in Leadership and Gerontology. Concordia University-Chicago, 7400 Augusta Street, River Forest, IL 60305.

References

- Archer T, Kostrezewa RM, Beninger RJ, Paloma T (2008). Cognitive symptoms facilitatory for diagnosis in neuropsychiatric disorders: Executive functions and locus of control. Neurotoxicity Research, 14 (2,3) 205–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton KW, Praetorius RT, & Smith-Osborne A (2016). Resilience protective factors in an older adult population: A qualitative interpretive meta-analysis. Social Work Research (40) 3 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Browne-Yung Kathryn & Walker Ruth & Mary Luszcz. (2015). An Examination of Resilience and Coping in the Oldest Old Using Life Narrative Method. The Gerontologist. 57, 2: pp. 282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazan A, & Dumitrescu SA (2016). Exploring the relationship between adolescent resilience, self-perception, and locus of control. Romanian Journal of Experimental Applied Psychology. 7(1) 283–286. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N, Lincoln Y (2005). Introduction: The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research In Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Chui H, Hay EL, Lumley MA, Grühn D, & Labouvie-Vief G (2014). Change in Coping and Defense Mechanisms across Adulthood: Longitudinal Findings in a European-American Sample. Developmental Psychology, 50(2), 634–648. 10.1037/a0033619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatt MA, Settersten RA, Ponsaran R, & Fishman JR (2013). Are “Anti-Aging Medicine” and “Successful Aging” Two Sides of the Same Coin? Views of Anti-Aging Practitioners. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(6), 944–955. 10.1093/geronb/gbt086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PB (2008) ‘Another wrinkle in the debate about successful aging: The undervalued concept of resilience and the lived experience of dementia’, International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 67(1), pp. 43–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen BM, Van Regenmortel T, & Abma TA (2011). Identifying sources of strength: resilience from the perspective of older people receiving long-term community care. European Journal of Ageing, 8(3), 145–156. 10.1007/s10433-011-0190-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B, & Lee JE (2014). Proactive Approaches to Successful Aging: One Clear Path through the Forest. Gerontology, 60(5), 466–474. 10.1159/000360222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Calasanti T (2015). Critical perspectives on successful aging: Does it “appeal more than it illuminates”?, The Gerontologist, 55, (1), pp. 26–33. 10.1093/geront/gnu027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRossa R (2005). Grounded theory methods and qualitative family research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 837–857. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y & Guba E (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, & Becker B (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71, 543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning L (2013). Navigating hardships in old age: Exploring the relationship between spirituality and resilience in later life. Qualitative Health Research, 23(4), 568–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mealer M, Jones J, Newman J, McFann KK, Rothbaum B, & Moss M (2012). The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: Results of a national survey. International Journal Of Nursing Studies, 49(3), 292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Kelly N, Kahana B, Kahana E, Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, & Poon LW (2015). Defining Successful Aging: A Tangible or Elusive Concept? The Gerontologist, 55(1), 14–25. 10.1093/geront/gnu044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priscila WÁM, Granero LAL, & Giancarlo L (2017). Association between depression and resilience in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(3), 237–246. doi:doi: 10.1002/gps.4619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Gwyther L, & Roberto K (Eds.) (2010). Resilience in Aging: Concepts, Research. New York: Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Reich JW, Zautra A, & Hall JS (2010). Handbook of Adult Resilience. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD (2014). Psychological Well-Being Revisited: Advances in Science and Practice. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10–28. 10.1159/000353263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C, and Singer B (2003). Flourishing under fire: Resilience as a prototype of challenged thriving In Keyes CLM & Haidt J (Eds.), Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 15–36). Washington, DC: APA. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C, Friedman E, Fuller-Rowell T, Love G, Miyamoto Y, Morozink J, Radler B, Tsenkova V (2012). Varieties of resilience in MIDUS. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(11), 792–806. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00462.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancassiani F, Pintus E, Holte A, Paulus P, Moro MF, Cossu G, Angermyer M, Carta M, Lindert J (2015). Enhancing the Emotional and Social Skills of the Youth to Promote their Wellbeing and Positive Development: A Systematic Review of Universal School-based Randomized Controlled Trials. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health : CP & EMH, 11(Suppl 1 M2), 21–40. 10.2174/1745017901511010021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schetter CD, & Dolbier C (2011). Resilience in the Context of Chronic Stress and Health in Adults. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(9), 634–652. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00379.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, & Corbin JM (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck I, & Anderson L (2014). Forgiveness, Flourishing, and Resilience: The Influences of Expressions of Spirituality on Mental Health Recovery. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(4), 277–282. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2014.885623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, Reeve J, Allen. (2012) The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. The Gerontologist, 52: 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles JL, Wild K, Kerse N, & Allen RE (2012). Resilience from the point of view of older people: ‘There’s still life beyond a funny knee’. Social Science & Medicine, 74 (3), 416–424. Doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle G, Bennett KM, & Noyes J (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9, 8 10.1186/1477-7525-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]