Abstract

There is growing evidence that the problematic use of mobile phone is an evolving problem. Although some studies have noted a greater prevalence in the Middle East, intercultural differences have not been sufficiently studied to date. The present study, therefore, aims at reviewing Iranian published studies on the problematic use of mobile phone in Iran. This study was conducted as a review study. For this purpose, we searched all published studies in this field that were conducted in Iran and reviewed all of the articles by studying the prevalence of the problematic use of cell phone in Iran, the adopted measuring instruments, the employed terms, predictors of the problematic use of cell phone, and the consequences of the problematic use of cell phone. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 47 articles were selected for evaluation. Among the problematic consequences, sleep disturbance was the most studied factor. Additionally, gender, feeling of loneliness, attachment stiles and age were mostly referred to as predictors. In addition, the reported prevalence varied from 0.9% to 64.5%, depending on the studied population and the measuring instruments. The diversity of reported prevalence rate of problematic use of mobile phone in Iran can be related to the ambiguity of the concept of “problematic use” and the diversity of the employed measuring tools. Thus, care should be taken in generalizing and interpreting the results.

Keywords: Addiction, behavioral addiction, cell phone addiction, Iran, mental health, mobile phone, problematic use

Introduction

In recent years, using mobile phones, especially the new generation of smartphones, has increased dramatically due to several services and facilities that they provide. Despite abundant and undeniable benefits of this new technology, there are many concerns about its potential psychological and social disadvantages. A serious concern among all is the problematic use of mobile phone, which is defined as the inability to regulate cell phone usage, which may have negative effects on daily lives of the users.[1]

Various definitions and terms have been proposed to describe the “Problematic Use of Mobile Phone.” Bianchi and Phillips described excessive and/or problematic use of a mobile phone based on the addiction literature, which consists of tolerance, escape from other problems, craving, withdrawal, and negative outcomes in the user's life.[2] Jenaro et al. used the “cell-phone overuse” term that is associated with other behavioral patterns, such as emotional dependence, and has negative impacts on the users' lives.[3] They used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)[4] criteria for impulse control disorders to assess the cell phone overuse, and also developed a scale by eliminating three items out of ten criteria for the pathological gambling. Moreover, in describing the problematic use of mobile phone, the “addiction” term is also used.[5,6] De-Sola Gutiérrez described the symptomatology of the problematic use of mobile phone in comparison with the DSM- Vcriteria for compulsive gambling and substance use as: problems and conscious use in dangerous situations or in forbidden contexts, social and family conflicts, loss of interest in other activities, the persistence of the behavior despite negative effects, difficulty in controlling, frequent and constant checking of phone in very short periods of time with sleep disturbances and insomnia, tolerance, overuse, need to be connected, need to quickly respond to messages, craving, and irritability and anxiety unless the mobile phone is available.[7]

Because the problematic use of mobile phone can have many negative consequences, for example sleep disturbances,[8,9,10] reduced academic performance,[11] stress,[10] and mental health symptoms,[9] several studies tried to identify predictive factors for it over the past decade. Studies show that various factors are associated with it, which can predict the problematic use of mobile phone, as follows: psychological factors such as extraversion personality traits,[2,12,13] impulsivity,[14,15] depression,[13,16,17,18] anxiety,[16] social stress,[5] anxious attachment style,[6] low self-esteem,[2] and feeling of loneliness;[19] demographic characteristics such as age[5] and gender;[5,20,21] and the cell phone use pattern.[5] The prevalence of the problematic use of mobile phone in different communities varies from 0% to 38%, according to a review study by Eduardo et al.[22] In addition, some studies have noted a greater prevalence in the Middle East.[7] This variation in the prevalence rate can be due to different definitions and measuring instruments, and diversity of the studied populations and countries.

Although there are some review articles for example,[1,22] intercultural differences have not been sufficiently studied to date. According to published statistics, the number of Iranian mobile phone users is over 53 million[23] and 69% of them have a smartphone.[24]

The present study, therefore, aims at reviewing Iranian published studies on the problematic use of mobile phone by studying the prevalence of the problematic use of cell phone in Iran, the adopted measuring instruments, the employed terms, predictors of the problematic use of cell phone, and the consequences of the problematic use of cell phone.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

The search process was conducted in May 2017. Inclusion criteria used for the present review were: (i) to assess the problematic use of mobile phone, (ii) to be published in a peer-reviewed journal (iii) to be written by Iranian researchers (affiliation: Iran), (iv) published in Farsi or English language, and (v) without limited by time period. The search process was conducted in two paths: to search articles that were published in Farsi language and to search articles that were published in English language.

For articles that be published in Farsi language, Iranian electronic databases were searched, including: SID (http://sid.ir), Noormags (http://www.noormags.com), Magiran (http://www.magiran.com), and Ensani portal (http://www.ensani.ir).

The searching terms have been: “Phone,” “Cell phone,” “Mobile,” and “Smartphone” in the title, abstract, or keywords. In addition, we did not limit the searches by time period (year) in order to locate the maximum number of eligible reports.

For articles that be published in English language, Google Scholar and PubMed were searched. In Google Scholar, Iran AND (addiction OR overuse OR dependency OR problematic use) AND (Phone OR Cell phone OR Mobile OR Smartphone) were searched in the title of the articles. In PubMed, Affiliation: Iran AND Title/Abstract: Phone AND Title/Abstract: (addiction OR overuse OR dependency OR problematic use) were searched. The searches were not limited by time period (year).

Study selection

A total of 788 studies that be published in Farsi language (SID n = 160; Noormags n = 128; Magiran n = 431; Ensani portal n = 69) were initially identified. All of these papers had their titles and abstracts screened, by excluding 649 duplicated or irrelevant papers, 139 studies were left. Full texts of these selected studies were then further examined for eligibility. Forty studies were identified that they concerned about “overuse,” “high use,” “problematic use,” and “addiction” or “dependence” on mobile phone. Six of them were excluded for the following reasons: five articles only investigated particular applications of mobile phone, such as texting with the short message service and social networks, and one paper was an editorial letter. Finally, 34 articles were selected and analyzed for this review.

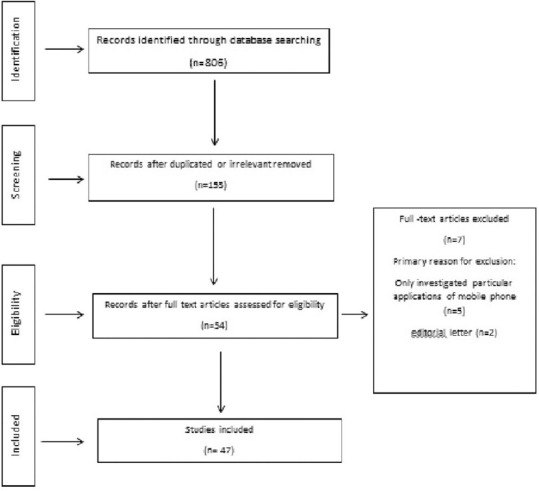

A total of 18 studies that be published in English language (Google Scholar n = 6; PubMed n = 12) were initially identified. All of these papers had their titles and abstracts screened, by excluding duplicated or irrelevant papers, 14 studies were left. Full texts of these selected studies were then further examined for eligibility. One paper, which was an editorial letter, was excluded. Finally, 13 articles were selected and analyzed for this review. The flowchart for the selection process is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature search

Quality assessment

A formal assessment of article quality was performed by using the Appraisal of Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS).[25] AXIS encourages consideration of risk of bias and quality of reporting for each component of the study design and allows users the flexibility of a subjective assessment of overall quality. AXIS contains twenty items and evaluates various aspects. Each question in the checklist can be scored from 0 to 1, and the minimum and maximum checklist scores are 0 and 20, respectively. The checklist design of the AXIS does not provide a cutoff numerical score for study eligibility. Articles which met fewer criteria should be interpreted with caution.[26] Each article was evaluated separately by at least two authors. The evaluation results were then compared. If there was a dispute, that article would be reviewed at the same time and the differences would be discussed and agreed upon. Based on the evaluation results of the selected articles, the minimum quality score was 10 (only one article), the maximum score was 18, and the average score was 14.41.

Data extraction

The following pieces of information were extracted from the selected articles:

The expertise of the corresponding authors

The release date of each article

The employed term

The adopted measuring instruments (i.e., the questionnaires)

The prevalence of the problematic use of cell phone

The consequences of the problematic use of cell phone

Predictors of the problematic use of cell phone.

Because of different tools and types of variables, and high heterogeneity of the studies, no meta-analysis was done.

In reporting these results, the terms referenced here are the ones used by the authors, as much as possible. The extracted specialized terms in the studied Persian papers had been translated from English to Farsi. Therefore, if the original English terms were provided in the article, we are citing those original terms, otherwise the closest technical terms have been translated to English, based on the available terms in the literature.

Results

Investigating the expertise of the corresponding authors of the 47 selected articles showed that the problematic use of mobile phone has attracted the attention of various study fields including medical sciences,[27] safety engineering,[28,29] curriculum planning,[30,31] psychiatry,[32,33] social sciences,[34] educational technology,[35] communications,[36,37] educational management,[38,39] health education,[40,41,42,43,44,45] counseling,[46,47] nursing,[48,49,50,51,52,53] epidemiology,[54,55] and psychology.[56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73] The findings also showed that problematic use of mobile phone was investigated the most by psychologists because they constituted up to half of the corresponding authors.

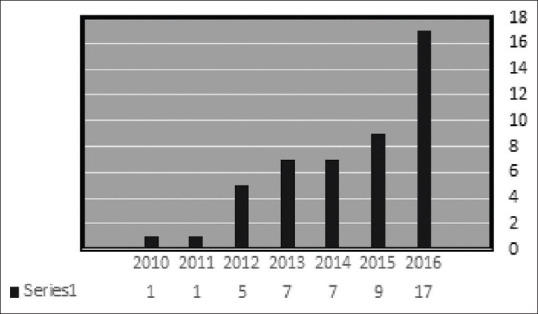

Out of 155 authors contributing to the 47 studied articles, the names of only 14 authors were repeated in more than one article. This suggests that problematic use of mobile phone had been an interesting topic for many, but not much of a concern to be investigated in a series of papers. Moreover, the articles were all published in different journals, indicating no special journal or a certain issue of a journal is dedicated to this topic. Regarding the type of the studies, out of the 47 analyzed articles, 46 were quantitative studies (with cross-sectional and correlational design), while only one study was qualitative.[37] The first article about the problematic use of mobile phone was published in 2010, and since 2012, there has been an increasing trend in the number of articles published in this field reaching to its highest point of 17 articles released in 2016 [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

The number of articles published each year

The employed terms

Numerous terms such as addiction, dependency, overuse, problematic use, high use, and excessive use were employed to address the problematic use of mobile phones [Table 1]. Out of the 47 articles in the current review, the term “addiction” was used in 18 studies (38.3%),[30,31,32,34,36,37,42,48,53,56,57,61,62,63,66,68,70,71] “dependency” was used in 11 studies (23.4%),[35,39,41,42,49,50,51,60,64,65,69] “overuse” in nine studies (19.1%),[27,28,29,40,45,46,47,55,58] “problematic use” in five (10.6%) of the studied papers,[59,63,67,72,73] “high use” appeared in three studies (6.4%),[33,38,52] and “excessive use” appeared in one study (2.1%).[44] It should be noted that these reported percentages are based on the terms used in the title, or in the abstract if not mentioned in the title. Worth mentioning, most of the studies used different terms in the main body of the article without specifying the employed terms or phrases.

Table 1.

The frequency (percentage) of the employed terms

| Term | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Addiction | 18 (38.3) |

| Dependency | 11 (23.4) |

| Overuse | 9 (19.1) |

| Problematic use | 5 (10.6) |

| High use | 3 (6.4) |

| Excessive use | 1 (2.1) |

Although in the introduction of each of these articles, several definitions and explanations were provided for the concept of the problematic use of mobile phone and its signs by referring to non-Farsi literature, almost none of them provided an explicit definition for the terms to clearly indicate the attitude of the author(s) toward the topic. Possibly, the employed measuring instruments can be considered as the operational definitions of the authors' intended concepts.

Evaluating and measurement

Out of the 46 quantitative studies, one study was carried out to develop and validate a questionnaire for addiction to mobile phone.[71] Two studies[63,72] assessed psychometrically the scale of the Problem of Mobile Phone Use, developed by Bianchi and Phillips;[2] one study[54] assessed psychometrically the scale of Cellular Phone Questionnaire, developed by Toda et al.;[74] one study[42] assessed psychometrically the Persian version of Mobile Phone Addiction Index developed by Leung;[21] one study[65] assessed psychometrically the Persian Version of Test of Mobile Phone Dependency developed by Igarashi et al.;[75] and one study assessed Semi-Structured Clinical Interview for Mobile Phone Addiction Disorder.[32] Five studies used questionnaires developed by the authors themselves.[22,36,38,52,70] Other 26 articles adopted the questionnaires to measure the intended variables. These questionnaires, in order of frequency, are as follows: Cell-Phone Over-Use Scale developed by Jenaro et al.[3] used in 12 studies;[28,29,40,46,47,48,55,58,59,61,67,73] Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale developed by Bianchi and Phillips,[2] used in 7 studies;[27,34,44,45,56,60,68] Cell phone Addiction Scale developed by Koo,[76] used in 6 articles;[31,39,49,50,51,69] Mobile Phone Addiction Index developed by Leung,[20] used in 4 articles;[41,43,62,66] Mobile Phone Usage Behaviour Questionnaire developed by Hopper and Zhou,[77] used in 2 studies;[30,35] Mobile Phone Addiction Questionnaire developed by Jafarzadeh,[78] used in one study;[64] Smartphone Addiction Scale developed by Kwon,[79] used in one article;[53] and Mobile-Phone Addiction Questionnaire developed by Savari,[71] used in a study.[57]

Prevalence

Because various studies employed different measuring instruments to evaluate the problematic use of mobile phone in different populations, various outcomes were also reported [Table 2].

Table 2.

The prevalence of problematic use of mobile phone

| Author | Scale | Population | Age range/mean (SD) of the statistical population | Sample size | Sampling method | Prevalence rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khazaei et al., 2012[50] | Cell Phone Addiction Scale (Koo, 2009) | Students of Birjand City | 15-20 years | 637 | Cluster sampling | 1.2% addiction 3.4% severe 95.% moderate |

| Khazaeib et al., 2013[49] | Cell Phone Addiction Scale (Koo, 2009) | Students of Islamic Azad University, Birjand Branch | Mean: 22.16 SD: 3.39 |

312 males: 200 Females: 112 |

Systematic random sampling | 1.9% addiction 7.4% severe 90% moderate |

| Khazaeia et al., 2013[51] | Cell Phone Addiction Scale (Koo, 2009) | Students of Birjand University of Medical Sciences | Mean: 17.5 SD: 1.75 |

697 males: 280 Females: 417 |

Systematic random sampling | 0.9% addiction 6% severe 93% moderate |

| Mansourian et al., 2014[41] | Mobile Phone Addiction Index (Leung, 2007) | Students of Tehran University of Medical Sciences | Not explicated | 405 males: 135 Females: 270 |

Stratified sampling method | 25.4% severe 50.4% moderate 24.2% low |

| Yahyazadeh et al., 2016[53] | Smartphone Addiction Scale (Kwon, 2013) | Nursing students of Medical Sciences Universities in Tehran | Mean: 21.47 SD: 7.12 |

150 | Quota cluster method | 9.3% addiction |

| Akbari et al., 2016[29] | Cell-Phone Over-Use Scale (Jenaro et al., 2007) | Students of Neyshapour University of Medical Sciences | Mean: 20.4 SD: 1.6 |

230 93 males 137 females |

Not reported | 8.7% high 80.5% moderate 10.8% low |

| Atadokht 2016[58] | Cell-Phone Over-Use Scale (Jenaro et al., 2007) | Students of Mohaghegh Ardabili University | Mean: 21.45 SD: 2.41 |

400 200 males 200 females |

Cluster random sampling | 5.5% high 81.5% moderate 13% low |

| Sayyah et al., 2016[27] | Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale (Bianchi and Phillips, 2005) | Students of Ahvaz Joundishapour University of Medical Sciences | Not reported | 195 95 males 100 females |

Cluster random sampling | 18.5% high 67.2% moderate 14.4% low |

| Babadi-Akashe et al., 2014[30] | Questionnaire of behavior associated with mobile phone use (Hooper and Zhou, 2007) | Students of Shahrekord Payame Noor University, Islamic Azad University, and University of Medical Sciences | Not reported | 296 students 57.10% male, 49.90% female |

Randomly | Habitual behaviors (21.49%), addiction (21.49%), intentional (21.49%) |

| Mazaheri et al., 2014[43] | Mobile phone Addiction Index (Leung, 2008) | Isfahan University of Medical Sciences students | Mean: 20.96 SD: 2.32 |

1180 students 65.5% female 34.5% male |

Convenience | Addiction 56.2% for female 64.5% for male |

| Norouzi Parashkouh et al., 2016[48] | Cell-Phone Over-Use Scale (Jenaro et al., 2007) | High school students in Rasht | Mean: 16.28 SD: 1.01 |

581 students 53.5% female 46.5% male |

Stratified sampling method | 103 (7/17%) high 451 (6/77%) moderate 27 (6/4%) low |

| Barati et al., 2016[40] | Cell-Phone Over-Use Scale (Jenaro et al., 2007) | Students living in dormitories at the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences | Mean: 21.3 SD: 2.1 |

300 students 60% female 40% men |

Stratified sampling method | 32% high 26.8% moderate 41.2% low |

| Alavi et al., 2016[32] | Semi- structure Interview for Mobile Phone Addiction Diagnosis | students of Tehran universities | Mean: 24.06 SD: 4.8 |

250 students 51.2% female 48.8% male |

Not reported | 13% were addicted |

| Mohammadbeigi et al., 2016[55] | Cell-Phone Over-Use Scale (Jenaro et al., 2007) | students of Qom University of Medical Sciences | Mean: 21. 8 SD: 3.2 |

380 students 69.5% female 30.5% male |

Proportional stratified sampling | Over-use=10.7% |

| Eyvazlou et al., 2016[28] | Cell-Phone Over-Use Scale (Jenaro et al., 2007) | Occupational Health and Safety (OH&S) students in five universities of medical sciences in the North East of Iran | Mean: 20.4 SD: 1.6 |

450 students 64% female 36% male |

Not reported | 4.6% Overuse 84.6% moderate 10.8% low |

| Pourrazavi et al., 2014[44] | Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale (Bianchi and Phillips, 2005) | Universities students in Tabriz | 18-33 years | 476 students 285 females 190 males |

2-stage random sampling | 128 (26/9%) over users 52.3% (67/128) male |

SD=Standard deviation

According to Table 2, 16 out of 46 articles reported the percentage of prevalence, which varied from 0.9% to 64.5%, depending on the population studied and the measuring instruments employed. All studies were performed by correlational design and have been conducted in Iran.

Consequences and predictors (A, B)

Regarding the employed methods and complexity of the relationships between variables, causal relationships could not be inferred. However, considering the nature of the studied variables and the approaches of the authors and their interpretations, the studies could be divided into two groups: the ones identifying the predictive variables of problematic use of mobile phone, and the ones examining the consequences of it.

A: Consequences

The problematic use of mobile phone can negatively affect the quality of sleep;[28,29,33,55,58] quality of life;[46] educational self-concept;[39] academic engagement;[39] the motivation for advancement;[59] academic performance;[33,59] mental health;[27,28] social interactions;[38] and feeling of loneliness;[41] and also can increase academic burnout,[31] aggression,[50] anxiety,[68] and depression.[40]

The relationship between problematic use of mobile phone and sleep quality was investigated in five studies. The results showed a significant and direct relationship between the problematic use of mobile phone and variables such as usual sleeping time, usual awaking time, awake before sleep, subjective sleep quality,[58] sleep latency, sleep disturbance, day time dysfunction,[28,29,58] and the use of sleep medication.[28,29] It was also found that problematic use of mobile phone accounts for 12%–29% of the significant variance observed in the studies, and 29% of the variance of total sleep quality can be predicted by the problematic use of mobile phones.[58] In general, there was a positive and significant correlation between the amount of mobile phone use and sleep disturbance.[33] One study found a negative and significant relationship between the overuse of mobile phone and total quality of life, mental health dimensions, general health, social function, and energic-fatigue. In other words, it has been shown that rise in the overuse of mobile phones is associated with declining in social function, energy, general health, and mental health, therefore, the quality of life.[46] These results were in line with those of another study that examined the relationship between the overuse of mobile phone and mental health, which also reported a negative and significant relationship between mental health and the amount of mobile phone use, to such an extent that the more mobile phones were used, the more mental health was jeopardized.[27]

Studies conducted on student populations showed a significant and negative relationship between problematic use of mobile phone and academic self-concept, passion for school,[39] achievement motivation,[59] and academic performance.[33,59] A study concluded that by increasing the problematic use of mobile phone, the achievement motivation reduces, and academic performance disrupts. In another student study, a significant and positive relationship was found between the use of mobile phone and academic failure, so that with the increase in the use of mobile phones, academic failure increases.[38] In addition, a significant and positive correlation between the problematic use of mobile phone and academic burnout was reported, which could predict academic exhaustion, academic cynicism, and academic inefficiency.[31]

With increased use of mobile phones, the social interactions among students were reduced,[38] and a significant and negative correlation was observed between the problematic use of mobile phone and the feeling of loneliness.[41]

In another study, all types of aggression (physical, verbal, anger, and hostility) showed to have significant and positive correlation with the problematic use of mobile phone.[50] Other studies showed that the problematic use of mobile phone had a positive and significant relationship with anxiety[68] and excessive users of cell phones were more depressed.[40]

B: Predictors

In the selected studies, the following variables were evaluated as predictors of problematic use of mobile phone: age,[36,43,44,45] gender,[29,36,41,43,44,45,47,49,51,53,73] marital status,[35,49] education level,[49] type of university,[35] having an opposite gender friend,[44,45] duration of use,[38,51,53] the type of use,[59] accommodation,[28,43] socioeconomic status,[43] family cohesion,[67] family relations,[70] social support,[41,62] parenting styles,[66] attachment styles,[56,60,61,64] identity styles,[57,69] personality traits,[64,69,73] self-regulation and self-control,[44,45] sensation-seeking,[34,60] feeling of loneliness,[41,62,66,67,69,80] mental health,[30,35,70] general health,[47] depression,[61] and self-esteem.[34,51]

The relationship between age and problematic use of cell phone in some studies was evaluated. In two studies conducted among the student population, no significant relationship between age and mobile dependency could be seen.[41,49] In a study conducted among residences of a city in Iran, a significant relationship was reported between age and the problematic use of cell-phone; the age group of 30 years old and higher had the highest and the age group of 15–19 years old showed the lowest level of the problematic use of mobile phone.[36] In another student study, cell phone addiction was related to age less than 25 year,[43] the variable of age (ranged 21–25 years old) was one of the predictors for overuse of mobile phone,[44,45] and individuals aged 21–25 years old, compared to the ones aged 25–45 years old, were 3.1 times more predisposed to overuse of cell phones.[45]

The relationship between problematic use of mobile phone and gender was investigated in some studies where females' average overuse of mobile phones was shown to be higher than males.[36,41,47,73] However, in other studies, the prevalence of the overuse of mobile phones was shown to be higher in males[43,44] or gender had no significant relationship with mobile phone overuse.[29,35,45,49,51,59]

The relationship between marital status and the problematic use of mobile phone was studied in five studies, but no consistent relation was concluded. Although the results of four of these studies indicated a significant relationship,[35,47,51,53] in one study, no significant relationship was found between marital status and the problematic use of mobile phone.[29] In three studies, the problematic use of mobile phone in single individuals was higher than married ones[35,47,53] However, in another study, the level of the problematic use was significantly higher in married couples than bachelors.[51]

A relationship between academic level and problematic use of mobile phone was found in one study, where PhD students showed higher cell phone dependency compared to other educational levels.[51] In addition, there was a relationship between the type of the universities (public or private) and problematic use of mobile phone;[35] however, the circumstance of such relation was not explained.

The associations between mobile phone use and having an opposite gender friend were statistically significant[44,45] so that students with opposite gender friend, compared with those without it, were 13.62 times more probable to mobile phone overuse (more than 75 times a day).[45]

In a student study, the findings showed a significant difference between mobile phone dependency in terms of duration (years) of mobile phone usage in such a way that 59.3% of people who used mobile phone <3 years had excessive dependency, while this rate was 35.1% and 5.6% for those who used mobile phone 3–6 years and more than 6 years, respectively.[49] In two other studies that estimated the duration of mobile phone use based on hours per day, a significant positive correlation between the hours of mobile phone use and problematic use of mobile phone was seen.[38,53] The relationship between the type of use and problematic use of mobile phone was studied in a study of high school students, and the results showed a significant relationship between the problematic use of mobile phone and using the cell phone as a device to “deepen the relationship,” for “communicating in an advanced manner,” “knowing the time and date,” and for “taking advantage of technical and recreational services.”[59]

Other predictive variables of problematic use of mobile phone were: socioeconomic status,[43] accommodation,[28,43] family cohesion,[67] family relations[70], parenting styles,[66] and social support.[41,62] Cell phone addiction was related to high socioeconomic status of family,[43] and cell phone addiction scores in students who lived in dormitory were significantly higher than other students[43] The family coherency negatively and significantly predicted the problematic use of mobile phone,[67] and there was a negative correlation between family relationships and their components (intimacy, coordination, and responsibility), and the problematic use. The family relationships variable could significantly explain the variance of the problematic use.[70] There was also a significant direct relationship between permissive and authoritative parenting styles and the problematic use, where permissive parenting style could predict the problematic use.[66] In addition, a significant and negative correlation was found between social support and problematic use of mobile phone.[41,62] Among the components of social support (family, friends, and significant others), the family support could predict the problematic use of mobile phone among students.[62]

The association of the style of attachment with the problematic use of mobile phone was evaluated in four studies and according to the results, there was a significant relationship between insecure[61,64] and anxious styles and problematic use of mobile phone.[56] Furthermore, problematic use of mobile phone was predictable via avoidant,[61] insecure,[64] anxious,[56] and general[60] attachment styles.

The relationship between identity processing styles (informational, normative, diffuse-avoidant, and avoidance) and problematic use of mobile phone was also evaluated in two studies. The results showed a positive and significant relationship between problematic use of mobile phone and the identity processing style of diffuse-avoidance.[57,69] There was also a significant and negative correlation between the normative identity processing style and problematic use of mobile phone.[69] Personality traits are other factors associated with the problematic use of mobile phone. According to the results of the studied papers, there was a significant and positive correlation between neuroticism,[64,69,73] openness[69], and problematic use of mobile phone. However, a significant and negative relationship was recognized between conscientiousness,[64,69] agreeableness,[64,69] extroversion,[73] and problematic use of mobile phone. Furthermore, neuroticism,[64,73] extraversion,[69,73] openness and conscientiousness,[69] sensation-seeking,[34,60] and self-regulation and self-control[44,45] could predict the problematic use of mobile phone.

Other factors associated with the problematic use of mobile phone include general health[47] and mental health.[30,35,70] The results of two studies showed that mental health could predict mobile phone addiction[30,70] and in this regard, obsession and paranoid ideation played the major role[35] Another study also found a significant and positive relationship between general health dimensions and overuse of mobile phone. In addition, the most contributing dimensions were social function and somatization for the total study population, as well as social function, somatization, and depression for girls. For boys, a positive significant relationship between the mobile phone overuse and the subscales of social function and somatization was found. Public health could predict the excessive use of mobile phone and accounted for 32% of its variance. Among the general health factors, social function was the most contributing factor and accounted for 28% of the variance in the overuse of mobile phone.[47] Feeling of loneliness is another variable that had a significant and positive relationship with the problematic use of mobile phone[62,66,67] and could predict it.[62] According to the results of a study, among the components of loneliness (romantic, family, and social), family and social loneliness could predict the problematic use of mobile phone.[62] Furthermore, results of another study showed that depression was one of the predictors of students' problematic use of mobile phone.[61]

One of the considered studies investigated the relationship between emotional intelligence and mobile phone dependency and showed a positive and significant correlation in this regard. This study also indicated that the emotional intelligence can predict the dependency on mobile phone.[49] Finally, although one of these studies showed a significant and negative correlation between mobile phone dependency and self-esteem,[51] in another study, the relationship between self-esteem and problematic use of mobile phone was not significant.[34]

Discussion

The current study aimed at investigating studies on the problematic use of mobile phone in Iran. Our results show an upward trend in the number of studies conducted over time, and the diversity in the researchers' expertise studying this issue, while psychologists constitute the dominant part. Almost none of the studies provided an explicit definition reflecting authors' attitude toward the topic, and various terms and tools were used. This issue has been also pointed out in a study by Gutierrez et al. and potentially challenges the conducted studies in this area.[7]

Considering the diversity of the employed measuring instruments and the studied populations (university/school students), range of the reported prevalence has been vast and varies from 0.9% to 64.5%. It should be considered that the prevalence samples are basically young students and adolescents. Furthermore, the studies have used self-reported questionnaires. Therefore, prevalence essentially refers to the population and may be different if using objective or validated criteria are used instead of subjective self-perception criteria.

There were some limitations to this study. The articles were searched and selected by the information available on databases and provided search facilities. Therefore, it is possible that some other researches carried out by Iranian researchers were not included in the current review due to lack of registration in such databases, not being published as papers, or lack of access due our inclusion criteria. The quality of the selected articles was not the same.

The current article describes available literature on risk factors for problematic mobile phone use and shows its multifactorial nature. This study is useful for researchers in understanding current trends and methodological issues. Given that one of the serious problems identified in the field was the diversity of terms and criteria, it can encourage other researchers to define and unify criteria with a view to perform quality studies that clarify this topic and permit appropriate conclusion.

Conclusion

According to the considered studies, problematic use of mobile phone adversely affects quality of life, quality of sleep, academic self-concept, academic engagement, achievement motivation, academic performance, psychological health, social interactions, and feeling of loneliness and increases academic burnout, aggression, anxiety, and depression. In addition, the amount of mobile phone use, family status (cohesion, relationships, parenting style, and support), attachment style, identity style, personality traits, general health, psychological health, feeling of loneliness, depression, and emotional intelligence are variables in correlation with problematic use of mobile phone, and can predict it. Because the evaluated studies had a cross-sectional design and the relationship among variables was complicated, inferring causal relationships was almost impossible. Considering the ambiguity of the concept of “problematic use,” the diversity of the employed measuring tools, and different qualities of the selected articles, caution is needed to generalize the results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study is related to a larger study conducted for a doctoral dissertation that was approved by the Ethical Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (ir.bmsu.rec. 1395:347). We would like to thank all the researchers who their studies have been used for this review.

References

- 1.Billieux J. Problematic use of the mobile phone: A literature review and a pathways model. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2012;8:299–307. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi A, Phillips JG. Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005;8:39–51. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenaro C, Flores N, Gómez-Vela M, González-Gil F, Caballo C. Problematic internet and cell-phone use: Psychological, behavioral, and health correlates. Addict Res Theory. 2007;15:309–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-4) 1994 doi: 10.1590/s2317-17822013000200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Deursen AJ, Bolle CL, Hegner SM, Kommers PA. Modeling habitual and addictive smartphone behavior: The role of smartphone usage types, emotional intelligence, social stress, self-regulation, age, and gender. Comput Human Behav. 2015;45:411–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuchang J, Cuicui S, Junxiu A, Junyi L. Attachment styles and smartphone addiction in Chinese college students: The mediating roles of dysfunctional attitudes and self-esteem. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2017;15:1122–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De-Sola Gutiérrez J, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Rubio G. Cell-phone addiction: A review. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:175. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahin S, Ozdemir K, Unsal A, Temiz N. Evaluation of mobile phone addiction level and sleep quality in university students. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29:913–8. doi: 10.12669/pjms.294.3686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao S, Wu X, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Tong S, Tao F. Effects of sleep quality on the association between problematic mobile phone use and mental health symptoms in Chinese college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(2):185. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomée S, Härenstam A, Hagberg M. Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults-a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samaha M, Hawi NS. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Comput Human Behav. 2016;57:321–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreassen CS, Griffiths MD, Gjertsen SR, Krossbakken E, Kvam S, Pallesen S. The relationships between behavioral addictions and the five-factor model of personality. J Behav Addict. 2013;2:90–9. doi: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smetaniuk P. A preliminary investigation into the prevalence and prediction of problematic cell phone use. J Behav Addict. 2014;3:41–53. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de-Sola J, Talledo H, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Rubio G. Prevalence of problematic cell phone use in an adult population in Spain as assessed by the Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale (MPPUS) PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y, Jeong JE, Cho H, Jung DJ, Kwak M, Rho MJ, et al. Personality factors predicting smartphone addiction predisposition: Behavioral inhibition and activation systems, impulsivity, and self-control. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elhai JD, Levine JC, Dvorak RD, Hall BJ. Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Comput Human Behav. 2016;63:509–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JH, Seo M, David P. Alleviating depression only to become problematic mobile phone users: Can face-to-face communication be the antidote? Comput Human Behav. 2015;51:440–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon YS, Paek KS. The influence of smartphone addiction on depression and communication competence among college students. Indian J Sci Technol. 2016;9(41):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bian M, Leung L. Linking loneliness, shyness, smartphone addiction symptoms, and patterns of smartphone use to social capital. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2015;33:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billieux J, Van der Linden M, Rochat L. The role of impulsivity in actual and problematic use of the mobile phone. Appl Cognitive Psychol. 2008;22(9):1195–210. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung L. Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. J Children Media. 2008;2:93–113. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedrero Pérez EJ, Rodríguez Monje MT, Ruiz Sánchez De León JM. Mobile phone abuse or addiction. A review of the literature. Adicciones. 2012;24:139–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Digital O. The Number of Smartphone Users in Iran ON Digital Editorial. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 May 12]. Available from: http://ondigitalir .

- 24.Agency ISP. National Survey ISPA. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 03]. Available from: http://ispair .

- 25.Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS) BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011458. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNamara J, Townsend ML, Herbert JS. A systemic review of maternal wellbeing and its relationship with maternal fetal attachment and early postpartum bonding. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0220032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sayyah M, Olapour A, Hoseini Ahangari A, Maashi F, Heidari A. Examine the relationship between mobile phone usage and psychological health and academic success among medical students. Educ Develop J. 2016;7:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eyvazlou M, Zarei E, Rahimi A, Abazari M. Association between overuse of mobile phones on quality of sleep and general health among occupational health and safety students. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33:293–300. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2015.1135933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akbari R, Zarei E, Dormohammadi A, Gholami A. Influence of unsafe and overuse of mobile phone on the sleep quality. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2016;21:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babadi-Akashe Z, Zamani BE, Abedini Y, Akbari H, Hedayati N. The relationship between mental health and addiction to mobile phones among University students of Shahrekord, Iran. Addict Health. 2014;6:93–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosseinpour E, Asgari A, Ayati M. The relationship between addiction to the Internet and mobile phone with students' academic burnout. Inform Communication Technol Educ Sci. 2016;6:59–73. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alavi SS, Mohammadi MR, Jannatifard F, Mohammadi Kalhori S, Sepahbodi G, BabaReisi M, et al. Assessment of semi-structured clinical interview for mobile phone addiction disorder. Iran J Psychiatry. 2016;11:115–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fazl Ali M, Farshidi F. Study of the use of mobile phones and their relationship with the sleep quality and academic performance of high school students. Inform Communication Technol Educ. 2016;6:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Divband F. Relationships between sensation seeking, leisure boredom, and self-esteem, with addiction to cellphone. Psychol Res. 2012;15:30–47. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zamani BE, Babady Akasheh Z, Abedini Y. Predicting the relationship between students' addiction behaviors to cellar phones and their demographic and psychological characteristics of Shahrkord Universities. Appl Soc. 2016;27:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Afkhami HS. Addictive mobile phone usage. Soc Soc Issues Iran. 2013;4:67–90. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kowsari ME, Amoori A. The patterns of the Iranian youth usage of cell phones (functions and dysfunctions in daily life) Soc Stud. 2012;19:259–87. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faghih-Aram B, Ebrahimi Z, Zargham M. Psychosocial harms caused by the use of mobile and Internet among students. Inform Communication Technol Educ. 2016;6:111–28. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karimianpour G, Karami A, Ahmadi T. The role of mobile dependency in the prediction of academic self-concept and school engagement of students. Educ Res. 2016;11:51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barati M, Moloudi G, Karimi F, Afshari M, Mohammadi Y, Etesamifard T. Association between cellphone overuse and depression among medical college students in Hamadan, West of Iran. Avicenna J Neuro Psycho Physiol. 2016;3:101–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansourian M, Solhi M, Adab Z, Latifi M. Relationship between dependence to mobile phone with loneliness and social support in University students. Razi J Med Sci. 2014;21:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazaheri MA, Karbasi M. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of mobile phone addiction scale. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:139–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mazaheri MA, Najarkolaei FR. Cell phone and internet addiction among students in Isfahan University of medical sciences-Iran. J Health Policy Sustainable Health. 2014;1(3):101–5. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pourrazavi S, Allahverdipour H, Jafarabadi MA, Matlabi H. A socio-cognitive inquiry of excessive mobile phone use. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;10:84–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pour-razavi SA, Topchian A. Determination of the predictive role of self-regulation and self- control on overuse of cell phones by students. J Hamadan Univ Med Sci. 2015;22:152–60. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Golmohammadian M, Yaseminejad P, Naderi N. The relationship between cell phone over use and quality of life in students. J Kermansha Univ Med Sci. 2013;17:387–93. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yaseminejad P, Golmohammadian M, Yoosefi N. The study of the relationship between cell-phone overuse and general heath in students. Knowled Res Appl Psychol. 2012;13:60–72. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parashkouh NN, Mirhadian L, EmamiSigaroudi A, Leili E K, Hasandoost F, Rafiei H. Internet and mobile phone addiction among high school students: A cross sectional study from Iran. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2016;5(3):31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khazaei TB, Sharifzadeh G, Jahed Saravani M, Khazaei T, Hedayati H. The relationship between emotional intelligence and mobile dependency of students in Birjand Azad University. Modern Care. 2013;10:279–87. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khazaei T, Saadatjoo A, Dormohamadi S, Soleimani M, Toosinia M, Mullah Hassan Zadeh F. Prevalence of mobile dependency and adolescence aggression. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2012;19:430–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khazaei TA, SaadatJoo A, Shabani M, Senobari M, Baziyan M. Prevalence of mobile phone dependency and its relationship with students' Self Esteem. Knowled Health. 2013;8:156–62. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sahbaie F, Shokri S, Dayemi M, Poorzadi M. Pattern of mobile usage and its relation to the psychological state of Tehran University students. Med Council Iran. 2016;34:233–40. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yahyazadeh S, Fallahi Khoshknab M, Norouzi K. The prevalence of smart phone addiction among students in medical sciences universities in Tehran. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2016;26:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alavi SS, Maracy MR, Jannatifard F, Ojaghi R, Rezapour H. The psychometric properties of cellular phone dependency questionnaire in students of Isfahan: A pilot study. J Educ Health Promot. 2014;3:71. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.134822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mohammadbeigi A, Absari R, Valizadeh F, Saadati M, Sharifimoghadam S, Ahmadi A, et al. Sleep quality in medical students; The impact of over-use of mobile cell-phone and social networks. J Res Health Sci. 2016;16:46–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Allahyari A, Heidari S, Jian F. Attachment styles, addiction to mobile phones and how to use it in students. Psychol Mod Methods. 2015;6:87–103. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Askarizadeh G, Poormirzaei M, Hajmohammadi R. Identity processing styles and cell phone addiction: The mediating role of religious coping. Res Religion Health. 2016;3:18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Atadokht A. The relationship of cell phone overuse with psychopathology of sleep habits and sleep disorders in university students. J Urmia Nurs Midwifery Faculty. 2016;14:136–44. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Atadokht A, Hamidifar V, Mohammadi I. Problematic use and type of mobile phone users in high school students and its relationship with academic performance and achievement motivation. School Psychol. 2014;3:253–66. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Babaei E, Azizi S, Golchobi R. Investigating the attachment and excitement styles as the projections of mobile dependence among teens. Stud Educ Psychol. 2014;20:53–76. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghasempour A, Mahmoodi-Aghdam M. The Role of Depression and Attachment Styles in Predicting Students' Addiction to Cell Phones. Addict Health. 2015;7:192–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jena-abadi H. On the relationship between loneliness and social support and cell phone addiction among students. School Psycholo. 2016;5:146–53. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mohammadi Kalhori S, Mohammadi MR, Alavi SS, Jannatifard F, Sepahbodi G, Baba Reisi M, et al. Validation and psychometric properties of mobile phone problematic use scale (MPPUS) in University students of Tehran. Iran J Psychiatry. 2015;10:25–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keyvankar M, Pakdaman M, Shahabizadeh F. Perceived childhood attachment patterns and personality characteristics in cell phone dependency. Develop Psychol. 2013;9:423–32. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mohammadi M, Alavi SS, Farokhzad P, Jannatifard F, Mohammadi Kalhori S, Sepahbodi G, et al. The validity and reliability of the Persian version test of mobile phone dependency (TMD) Iran J Psychiatry. 2015;10:265–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Monsheie G, Ghasemi Motlagh M, Govahi F, Mortazavi Kyasari F. The relationship between loneliness and parenting practices with student addiction to the mobile phone. Educ Res. 2015;11:101–12. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Narimani M, Ranjbar M. The role of loneliness and family cohesion in the tendency of teenagers to problematic use of mobile phones. Communication Res. 2016;23:45–62. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pourakbaran E. Assessment of using of emerging communication tools (cell phone, internet and satellite) among young adults and its association with anxiety, depression and stress. Fundamentals Mental Health. 2015;17:254–9. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rashidi A, Jafari T, Hojatkhah M, Moahammadi F, Mahboobi M, Zahedi A, et al. The relationship between personality traits, loneliness, and identity styles and dependence on mobile phone in students. Sadra Med Sci. 2015;4:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Savari k. The relationship between mental health and family relationships with cell phone addiction. Soc Psychol Res. 2013;3:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Savari K. Construction and validation of the mobile phone addiction questionnaire. Educ Measurement. 2014;4:126–42. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shayeghian Z, Rasoolzadeh Tabtabae K, Rahimi K, Parian S. The psychometric evaluation of mobile phone problem usage scale (MPPUS) Pajouhandeh J. 2012;17:246–51. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yaseminejad P, Golmohammadian M. Study the relationship of Big five factors of personality and problematic use of Cell-phone in students of University of Dezful. Soc Psychol Res. 2011;1:79–105. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Toda M, Monden K, Kubo K, Morimoto K. Cellular phone dependence tendency of female university students. Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2004;59:383–6. doi: 10.1265/jjh.59.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Igarashi T, Motoyoshi T, Takai J, Yoshida T. No mobile, no life: Self-perception and text-message dependency among Japanese high school students. Comput Human Behav. 2008;24:2311–24. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Koo HY. Development of a cell phone addiction scale for Korean adolescents. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2009;39:818–28. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2009.39.6.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hooper V, Zhou Y. Addictive, dependent, compulsive? A study of mobile phone usag. BLED proceed. 2007;1:38. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jafarzadeh E. Mobile Addiction and Its Relation with General Health of Students. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kwon M, Lee JY, Won WY, Park JW, Min JA, Hahn C, et al. Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS) PloS One. 2013;8(2):e56936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Elhai JD, Levine JC, Dvorak RD, Hall BJ. Non-social features of smartphone use are most related to depression, anxiety and problematic smartphone use. Comput Human Behav. 2017;69:75–82. [Google Scholar]