Abstract

In support of NASA’s Triton Hopper project, mechanical response data for solid nitrogen are needed for concept validation and development. Available mechanical properties data is sparse with only three known indentation measurements existing between 30 and 40 K. To generate more data, a custom instrumented hardness tester was developed to interface with a cryostat. The system was used to conduct cylindrical punch indentation testing at Triton-relevant thermodynamic conditions. Pressure versus displacement curves and hardness values were obtained. In the experiments the hardness ranged between about 2 kg/mm2 and 0.5 kg/mm2 in the aforementioned temperature range. A suspected brittle fracture is observed at lower temperatures in the range.

Keywords: Solid Nitrogen, Triton, Instrumented Indentation, Hardness, Cryocrystal

1. Introduction

Future missions to Neptune’s largest moon, Triton, and other space bodies such as those in the Kuiper Belt are expected to require collection of local ices as a propellant for surface vehicle propulsion1. Therefore, the properties of Triton’s principal surface ice, nitrogen, are desired2,3. The surface of Triton is estimated to have an atmospheric pressure of 1.6 Pa4 and a surface temperature range between 30-40 K5-8, which straddles the nitrogen α to β phase transformation temperature, 35.61 K9. Mechanical properties data on solid nitrogen (SN2) is extremely sparse, with only three known physical strength measurements reported in the literature. Trepp reported indentation hardness for SN2 ice single crystals created in a liquid-helium cooled cryostat using a stainless steel 90° conical indenter10. Later, Leonteva et al. conducted tensile testing on a variety of solid noble gas cryocrystals using a unique testing apparatus11. Most recently, Yamashita et al. conducted unconfined compression tests on 10 mm diameter cylinders of clear solid N2 ice12. For proposed collection mechanisms of SN2 on Triton missions, confined compressive hardness is a critical metric for engineering design.

Relatively recent advances in cryostat technology have enabled cryocrystals of gasses to be grown by condensation and subsequently solidification via a cryocooler rather than evaporative cooling. This improved ability to control crystallization should reduce the presence of bubble defects caused by the evaporative cooling growth process. Considering the cryostat technology of the time (1958), the crystals formed by Trepp, could contain voids or cracks causing reduced hardness and strength compared to completely dense ices.

2. Methods

An instrumented hardness tester was developed to interface with a custom-built cryostat. The cryostat is contained in a 0.48 × 0.57 × 0.28 m stainless steel vacuum chamber evacuated by a Leybold DB8 rotary vain vacuum pump in line with an Agilent Tv 81m turbomolecular pump. Cooling is provided by the second stage of a Cryomech PT405 pulse-tube cryocooler which is connected to the test cell. An aluminum sheet and a multi-layer insulation radiation shield surrounded the test cell. A 1.7 mm thick PTFE sheet was included against the inner cylindrical surface to promote solidification in one direction (bottom to top) encouraging continuous sample growth without cracks. The instrumented indentation system uses a commercially available 45 kg screw-driven load frame. A custom microcontroller system has been used to provide vertical motion control via a stepper motor and force measurement via an S-beam load-cell with appropriate signal amplification. The load cell is connected between the cross-head of the load frame and the vertical indentation shaft outside the cryostat. The shaft then passes through a double O-ring seal and into the upper part of the specimen chamber or downtube. The indenter probe head has a unique design. A copper cross-bar is mounted to the end of the indenter shaft. The titanium indenter probe is threaded into the lower surface of the cross-bar. With the indenter offset from shaft centerline, multiple indents per sample creation were possible by rotating the shaft and cross-bar assembly into a new position for each test, avoiding indenter contact with the previously deformed region of material.

To maximize indents per cycle a 2.54 cm offset from the center was chosen. Using a 2.25 mm diameter indenter and rule of thumb of five indenter-diameter separation13 allowing eleven indents per run. For proper rotational spacing of each indent, a keyed piece with numbering was fabricated and mounted on top of the shaft. This allowed consistent rotational locations to be used during and between runs. Data was collected in ascending order using positions two through eleven (position one was used to initially cool the indenter to thermal equilibrium with the specimen). Temperatures of the sample were measured and controlled by a Lakeshore 336, germanium resistance temperature detector (RTD) and heater attached to the outside of the sample cup. Accuracy of the sensor was ± 0.2 K, the majority of samples were taken within 0.2 K of their target temperature leaving control uncertainty of approximately 0.3 K. The indenter temperature was measured at the copper crossbar via a platinum RTD with an uncertainty of 0.25 K. Thermal equilibrium is achieved by bringing the indenter into contact with the specimen. After cooling the indenter in the sample, the crossbar temperature was measured at approximately 1.5 K above the sample temperature. Considering the temperature probe location, low thermal mass of the indenter, and thermal dead-end nature of the specimen container, it can be presumed that any temperature difference between sample and indenter was much less than 1.5K during data collection.

Once the tip had cooled (approximately 20 minutes), the indenter head was lifted and rotated to the desired position for testing. The apparatus is shown schematically in Fig. 1a and as a photograph in Fig. 1b.

Fig. 1.

(a) Schematic illustration of the hardness test apparatus and b) photograph of load frame on top of cryostat.

In this experiment, flat punch indenter geometry was chosen to eliminate the need for post-indent inspection of the residual impression. Alternatively, a self-similar pyramid or conical indenter geometry could have been used along with a known area-calibration function14 however, pointed tip geometry would considerably reduce the precision of surface detection. One down-side of using a flat punch; however, is that the indenter travel axis will have some amount of deviation from the specimen surface normal direction. This will cause both erroneously low hardness values, since the projected area will be higher, and initial surface contact with only one side of the indenter. In this case, however, the indenter is within typical machining tolerances of normal, so these effects are unlikely to influence the measurement.

The indenter shaft was highly polished; however, a non-negligible frictional force was still developed between the O-ring seal and the shaft. This force was calibrated out during post-processing of the data. To conduct an indentation test the stepper motor was engaged, driving the probe into the sample. The no-contact and nitrogen-contact forces are very different, indicating whether contact between the indenter and specimen was made. Force detection was used to determine the surface position of the sample. Known motor step count and lead-screw pitch were used to determine the depth of penetration into the specimen.

The data collected were stored in a .txt file containing timestamp, force, and position per line. The files were read and processed using MATLAB. Line numbers associated with the start and end displacement values were then picked and used to in conjunction with the MATLAB interpft function to interpolate the data. This smoothed out some erroneous points and allowed the O-ring drag forces to be removed thus zeroing the data. Drag data was collected twice at each rotational position and averaged to provide the zeroing data.

Samples were formed in an 82.5 mm diameter copper test cell from 99.999% pure gaseous nitrogen. After sealing the system and before cooling, the test cell was filled with nitrogen gas to 10 psi atm and then purged with a vacuum pump. This was repeated three times to minimize contamination. The cryocooler was then turned on, and the system began to cool. Nitrogen was then slowly added to the test cell from a small tank, separated from the main source tank via a needle valve. This small tank was used as a nitrogen buffer where the pressure change could be easily controlled, thus permitting fine control of the mass added to the test cell. The amount of nitrogen was determined from the known buffer tank volume and pressure change. Once the test cell reached the boiling point temperature of the nitrogen at the supply pressure, the flow of nitrogen into the test cell increased as liquid condensed in the test cell. Gravity causes this liquid to settle at the bottom of the test cell. Once enough mass was added to the system (approximately 40 mm of liquid depth), the nitrogen supply valve was closed and the sample was cooled to the desired test temperature over the course of several hours at a rate of approximately 0.166 K/min. The top surface of the specimen in the solid form should therefore be flat, planar, and normal to the gravity vector. Specimens are anticipated to be comprised of one or several single crystals, rather than accreted small crystals (snow). Kjems and Dolling15 in their studies on the cubic α-phase of nitrogen were very careful to cool samples slowly across the β-α phase transformation, but no indication was given as to what rate is required to avoid cracking when moving through the phase transition. Additional system and operation details are available in a forthcoming thesis from Hacker16.

3. Results and Discussion

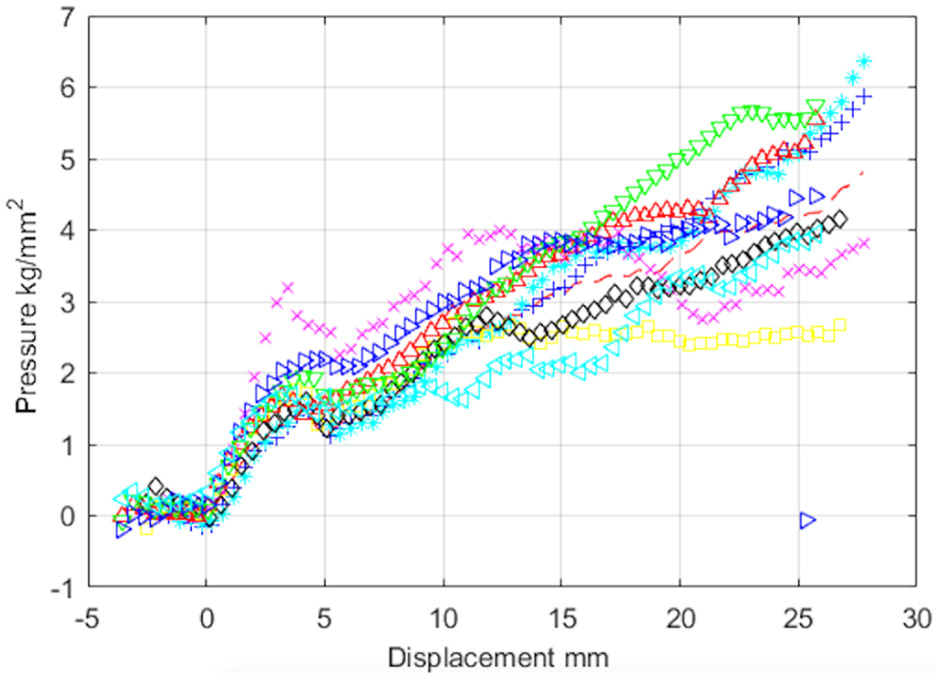

Typical corrected pressure versus displacement curves are shown in Fig. 2 for 32 K. Other temperatures are similar. The curves show that a rapidly and nominally linearly increasing initial force is generated as the indenter tip makes contact with the ice surface. This suggests that the indenter probe is normal to the specimen surface In most of the indentation tests at lower temperatures, a decrease in load after about 3-4 mm of penetration into the surface is observed. We believe this to be a brittle fracture of the ice because at higher temperatures in the range, the effect is less pronounced and, in some cases, not observed at all. Upon further indenter travel into the specimen surface, the load continues to increase as the ice flows.

Fig. 2.

Typical pressure versus indenter penetration depth curves for 32 K.

Consistent with Trepp and others, we see a marked change with temperature near the phase transition, with warmer temperatures behaving softer. From the multiple runs, average pressure vs. displacement curves were created by averaging each pressure for a given depth. Figure 3 shows the average behavior for each temperature over the range of temperatures studied.

Fig. 3.

Average pressure versus indenter penetration depth curves for temperatures between 30 and 40 K.

Hardness, H, is calculated by equation 1, where P is the maximum load before brittle fracture and A is the area of the indenter face, 3.98 mm2.

| (1) |

In cases where brittle fracture was difficult to discern, hardness was calculated using the load at 4 mm displacement. Hardness versus temperature for this work and that of Trepp is plotted in Fig. 4. Note, that Trepp’s data are graphically determined since numerical data are not presented in the original reference. Our hardness values are somewhat higher than those previously reported. As mentioned, previous hardness measurements used conical indenter geometry and may not be completely analogous to this work. Other influences may be defects in previously formed ices. It is also possible that heat conduction was not as well controlled in the 1958 experiment, due to the use of stainless steel components which have 2-3 times the thermal conductance of titanium components17,18.

Fig. 4.

Hardness versus temperature with comparison to the work of Trepp.

4. Conclusions

For the first time, the instrumented indentation technique has been used to collect mechanical behavior of solidified nitrogen. The samples were formed by heat removal without large pressure fluctuation and are anticipated to have fewer defects. Pressure versus displacement curves show increasing load with increasing indenter penetration. Which may indicate some degree of strain hardening in the material under confined compression conditions. Hardness values calculated at the peak load before a likely fracture event ranged from 0.5 kg/mm2 to 2 kg/mm2 between 30 K and 40 K. These values are harder than those previously reported in the literature, though the measurements may not be completely analogous. Other potential sources of discrepancy are internal material voids and heat conduction in previously reported experiments.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NASA grants numbered 80NSSC19K0250 and 80NSSC19K0251.

5. References

- 1.Oleson S & Landis G Triton Hopper: Exploring Neptune’s Captured Kuiper Belt Object. in Outer Solar System: Prospective Energy and Material Resources 367–428 (2018). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73845-1_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruikshank DP, Brown RH & Clark RN Nitrogen on Triton. Icarus 58, 293–305 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKinnon WB & Kirk RL Triton. (Elsevier Science Bv, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruikshank DP et al. Ices on the Surface of Triton. Science 261, 742–745 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conrath B et al. Infrared Observations of the Neptunian System. Science 246, 1454–1459 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broadfoot AL et al. Ultraviolet Spectrometer Observations of Neptune and Triton. Science 246, 1459–1466 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soderblom LA et al. Triton’s Geyser-Like Plumes: Discovery and Basic Characterization. Science 250, 410–415 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quirico E et al. Composition, Physical State, and Distribution of Ices at the Surface of Triton. Icarus 139, 159–178 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manzheliĭ VG & Freiman YA Physics of cryocrystals. (American Institute of Physics, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trepp C Schweiz. Arch. Angew. Wiss. Tech B24, 230 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonteva AV, Stroilov Yu. S. & Krupskii IN in Fiz. Kondens. Sostoyan XVI, (Nat. Acad. Sci, 1971). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamashita Y, Kato M & Arakawa M Experimental study on the rheological properties of polycrystalline solid nitrogen and methane: Implications for tectonic processes on Triton. Icarus 207, 972–977 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris DJ & Bahr David F. Nanoindentation: Localized Probes of Mechanical Behavior of Materials in Springer Handbook of Experimental Solid Mechanics 389–408 (Springer, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliver WC & Pharr GM An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res 7, 1564–1583 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kjems JK & Dolling G Crystal dynamics of nitrogen: The cubic α -phase. Phys. Rev. B 11, 1639–1647 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hacker Z Instrumented Indentation Testing of Solid Nitrogen at Triton Relevant Conditions - Unpublished.

- 17.Stainless Steels. (ASM International, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyer R, Welsch G & Collings EW Materials Properties Handbook: Titanium Alloys. (ASM International, 1994). [Google Scholar]