Abstract

Background

Picture archiving and communication systems (PACS) are ubiquitously used to store, share, and view radiological information for preoperative planning across surgical specialties. Although traditional PACS software has proven reliable in terms of display accuracy and ease of use, it remains limited by its inherent representation of medical imaging in 2 dimensions. Augmented reality (AR) systems present an exciting opportunity to complement traditional PACS capabilities.

Objective

This study aims to evaluate the technical feasibility of using a novel AR platform, with holograms derived from computed tomography (CT) imaging, as a supplement to traditional PACS for presurgical planning in complex surgical procedures.

Methods

Independent readers measured objects of predetermined, anthropomorphically correlated sizes using the circumference and angle tools of standard-of-care PACS software and a newly developed augmented reality presurgical planning system (ARPPS).

Results

Measurements taken with the standard PACS and the ARPPS showed no statistically significant differences. Bland-Altman analysis showed a mean difference of 0.08% (95% CI –4.20% to 4.36%) for measurements taken with PACS versus ARPPS’ circumference tools and –1.84% (95% CI –6.17% to 2.14%) for measurements with the systems’ angle tools. Lin’s concordance correlation coefficients were 1.00 and 0.98 for the circumference and angle measurements, respectively, indicating almost perfect strength of agreement between ARPPS and PACS. Intraclass correlation showed no statistically significant difference between the readers for either measurement tool on each system.

Conclusions

ARPPS can be an effective, accurate, and precise means of 3D visualization and measurement of CT-derived holograms in the presurgical care timeline.

Keywords: augmented reality, mixed reality, picture archiving and communication system, presurgical planning, new technology evaluation, medical imaging, surgery

Introduction

Picture archiving and communication systems (PACS) allow for easy storage and viewing of medical imaging information. Traditional PACS viewers present images in x-ray, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data on a 2-dimensional (2D) workstation screen to be examined by a surgical team in preparation for a complex procedure [1,2]. While these systems have been shown to be accurate and easy to use for the analysis of medical images [3], they are also limited by their requirement of a desktop computer, laptop, or smartphone screen [4]. Dias et al [5] report that 2 of the most common problems of traditional PACS are the mismatch between the 2D viewing screen and the real world and the accompanying lack of flexibility and efficiency of use.

Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) technologies have the potential to address these shortcomings. AR and VR alike allow for the realistic and interactive digital representation of objects in a 3D space. As such, both technologies are already successfully deployed across a diverse set of applications, including terrestrial navigation [6], architectural modeling [7], automotive engineering [8], and education [9]. The same properties could be applied to present a realistic overlay of medical devices and tools on patients’ anatomy in 3D space on a portable, shared visualization method.

Whereas VR presents an entirely digital representation of objects and their environment, AR allows for the overlay of digital holograms on a live real-world scene. In addition, many VR systems require a dedicated physical play space to allow for the experience of the completely immersive digital experience [10]. These characteristics make AR a more likely candidate for the development of interactive tools assisting the dynamic clinical workflow.

The potential of AR systems to assist in clinical tasks has been extensively reviewed by Uppot et al [11]. Possible use cases include supplementing radiology training; communicating with colleagues, referring clinicians, and patients; and aiding in interventional radiology procedures. Additional uses for AR in medicine include providing simulations for advanced life support training [12], visualizing patient anatomy including tumors [13], and guiding assistants during robotic surgery [14]. The increased spatial understanding of anatomy with AR has been shown to positively impact surgical care during laparoscopic surgery for visualizing hidden patient anatomy [15], resection of neurological tumors without causing new neurological deficit [16], and breast tumor resection by maximizing breast conservation [17]. Multiple other non–patient outcome benefits have been proposed, including overall operating room efficiency [18,19], and more specifically—reduced operating room time, increased surgical precision, and reduced radiation exposure [20].

In order to create an AR model suitable for presurgical planning, the medical image from a CT or MRI scan must first be segmented using a DICOM viewer to visualize only the object or organ of interest. The resulting image is passed onto an image processing software that renders the object’s volumes and surfaces into a 3D scalar field model. This model can later be loaded in a dedicated AR software designed for projecting the image onto an AR or mixed reality headset display. Similar technologies have evaluated the use of AR systems for the visualization of MRI data [21]. However, the focus of this study is the validation of CT-derived holograms. Although the visualization of CT-derived holograms has been assessed, measurement systems for these CT-derived holograms are rarely evaluated or utilized.

As AR becomes more widely used in presurgical planning, it is crucial to know that these systems meet the gold standard for medical image measurement. This study aims to validate the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of a novel ARPPS, compared to a standard-of-care PACS viewer, in order to support its use in the presurgical visualization and measurement of CT-derived imaging of patient anatomy and surgical tools.

Methods

Materials

A CT image data set was generated using Discovery CT750 HD (GE Healthcare). The object imaged was a CT dose meter phantom (model 137856101, GE Healthcare) compliant with the American College of Radiology standards. The PACS used for standard-of-care comparison was Osirix MD version 10.0 (Pixmeo SARL; FDA 510(k) K101342) [22]. The experimental PACS was the RadHA ARPPS version 3.3 (University of California, San Francisco) (Figure 1), as viewed on HoloLens generation 1 headset (Microsoft Corp). A MT-912 Digital Light Meter (Urceri) was used to measure the background light intensity.

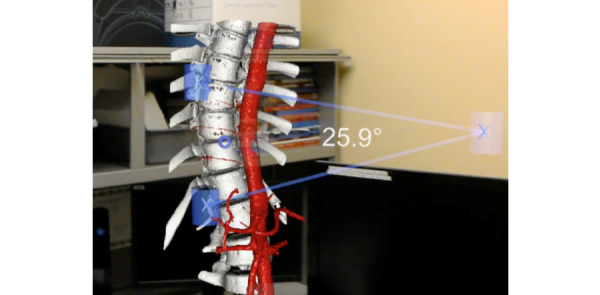

Figure 1.

The RadHA ARPPS version 3.3 displaying a spine model with a vascular model overlay and an angle measurement of thoracic kyphosis.

Procedure

The CT dose meter phantom DICOM (digital imaging and communications in medicine) file was converted to an OBJ file (object file, Wavefront Technologies) and uploaded to the ARPPS for viewing on the HoloLens. The circumference and angle measurement tools of both the standard PACS and the ARPPS were used to measure diameters (Figure 2) and angles, respectively, with reference to the manufacturer-specified parameters of the CT dose meter phantom (Figure 3).

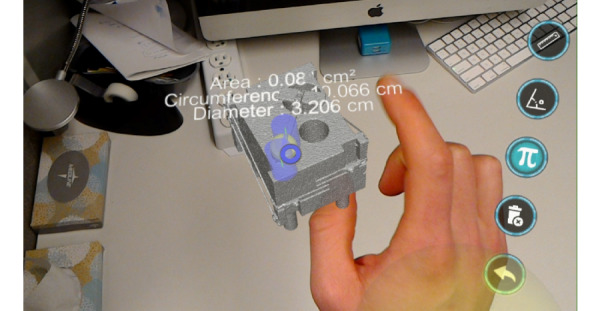

Figure 2.

The RadHA ARPPS version 3.3 displaying a computed tomography (CT)-derived 3D hologram of a CT dose meter phantom with diameter and circumference measurements and selectable icons.

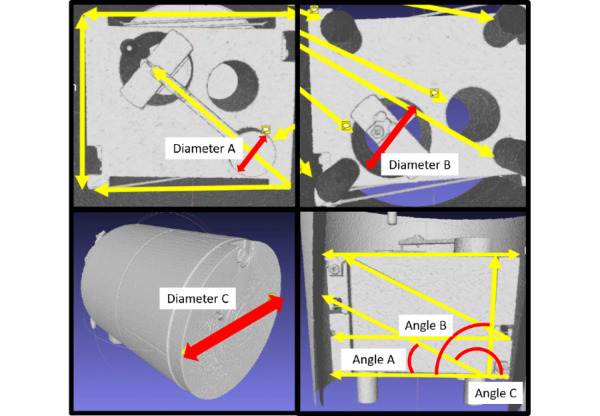

Figure 3.

Computed tomography (CT) dose meter phantom diameters and angles as per the manufacturer's specifications.

A range of low, medium, and high clinical measurements were selected for anthropomorphic correlation of the phantom’s diameter and angle parameters (Table 1). Two readers measured each of the phantom parameters 10 times independently of each other starting with the ARPPS. The readers were blinded to the manufacturer-provided measurements. Testing was completed in an office with a background light intensity of 152.1 lux.

Table 1.

Clinical significance of the CT dose meter phantom measurements.

| Object | Manufacturer-specified size | Clinical guideline |

| Diameter A | 3.215 cm | Mitral valve repair valve sizing [23] (mitral annulus diameter 3.15 cm) |

| Diameter B | 5.0 cm | Elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in women [24] (5.0-5.4 cm) |

| Diameter C | 21.31 cm | Pediatric abdominal diameter |

| Angle A | 26.57° | Scoliosis evaluation [25] (bracing Cobb angle 29-40°) |

| Angle B | 90.0° | Proximal tibial alignment [26] (normal lateral distal tibial angle 90°) |

| Angle C | 153.43° | Pediatric hip evaluation [27] (normal pediatric femoral shaft angle 160°) |

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel version 1903. The interrater reliability of the readers was verified using Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient for both the circumference and angle tools [28]. Shapiro-Wilk test was performed to verify the normality of the differences of each set of measurements in order to satisfy the requirements of performing a nonparametric method of analysis such as a Bland-Altman analysis [29]. Bland-Altman analysis was used to evaluate the agreement between measurements taken with the standard PACS and the ARPPS.

Results

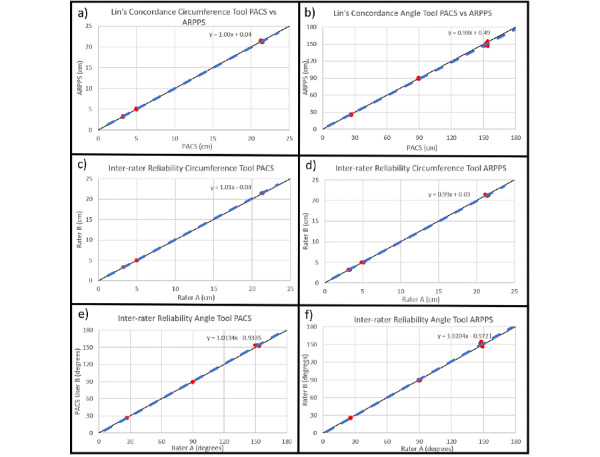

Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient showed almost perfect concordance of the standard PACS viewer and the ARPPS (Figure 4, Table 2). Additionally, no significant difference in interrater reliability was observed for the circumference and angle tool measurements for both the PACS and ARPPS separately (Figure 4, Table 2).

Figure 4.

Lin’s concordance plots of a) circumference tool, b) angle tool; interrater reliability plots of c) circumference tool for the picture archiving and communication system (PACS), d) circumference tool for augmented reality presurgical planning system (ARPPS), e) angle tool for PACS, f) angle tool for ARPPS.

Table 2.

Lin's concordance correlation coefficients and interrater reliability.

| Tools | Concordance correlation coefficient | Interrater reliability PACSa standard DICOMb viewer | Interrater reliability ARPPSc |

| Circumference tool | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.99 |

| Angle tool | 0.98 | 1.01 | 1.02 |

aPACS: picture archiving and communication system.

bDICOM: digital imaging and communications in medicine.

cARPPS: augmented reality presurgical planning system.

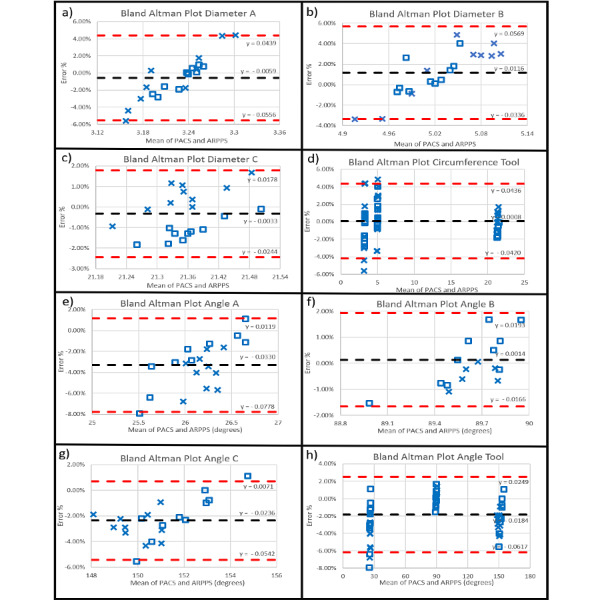

The Shapiro-Wilk tests failed to reject the null hypothesis of normality (Table 3). Bland-Altman plots evaluating the circumference tool showed an average bias of 0.08% with a 95% CI –4.20% to 4.36%. Bland-Altman plots evaluating the angle tool showed an average bias of –1.84% with a 95% CI –6.17% to 2.14%. The bias and confidence intervals of each of the 3 measures for the circumference and angle tools are reported in Table 3. The Bland-Altman plots of each of the measurements, as well as the combined measurements are shown for the circumference tool (Figure 5 a-d) and angle tool (Figure 5 e-h).

Table 3.

Shapiro-Wilk test for normality of differences and Bland-Altman analysis.

| Tools and measurements | Shapiro-Wilk test P value |

% Bias | Lower limits of agreement, % | Upper limits of agreement, % | |

| Circumference tool | |||||

|

|

Diameter A | .5607 | –0.59 | –5.56 | 4.39 |

| Diameter B | .4528 | 1.16 | –3.36 | 5.69 | |

| Diameter C | .3325 | –0.33 | –2.44 | 1.78 | |

| Combined | N/A | 0.08 | –4.20 | 4.36 | |

| Angle tool | |||||

|

|

Angle A | .8304 | –3.30 | –7.78 | 1.19 |

| Angle B | .9685 | 0.14 | –1.66 | 1.93 | |

| Angle C | .7211 | –2.36 | –5.42 | 0.71 | |

| Combined | N/A | –1.84 | –6.17 | 2.49 | |

Figure 5.

Bland-Altman plots for the circumference tool measurements for a) diameter A, b) diameter B, c) diameter C, d) all diameters combined, and of the angle tool measurements for e) angle A, f) angle B, g) angle C, h) all angles combined.

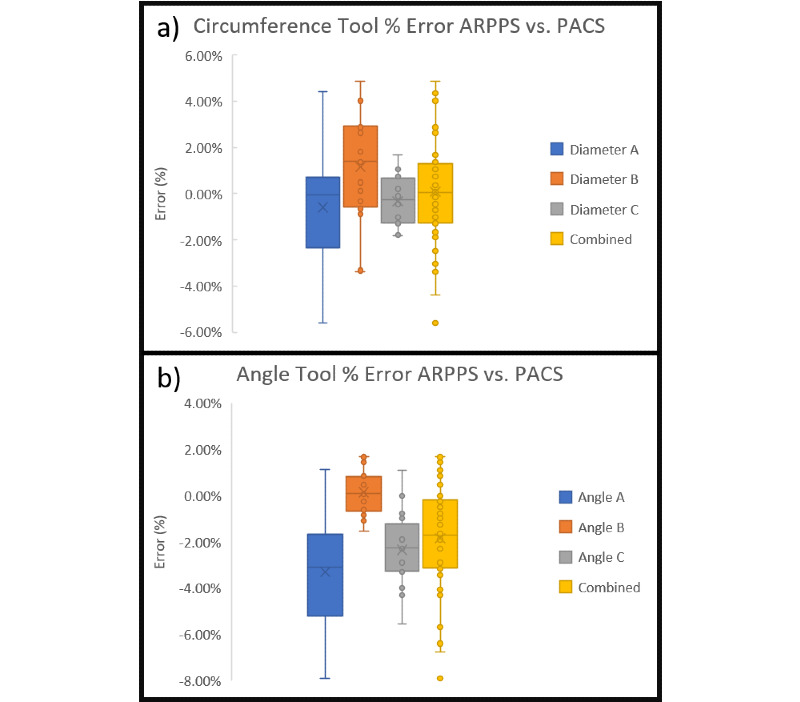

The variability of the percent error of each of the measurements using the ARPPS as compared to using the standard PACS are visualized in individual box plots in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Whisker plot comparisons of percent error of the augmented reality presurgical planning system (ARPPS) versus the standard picture archiving and communication system (PACS) for a) circumference tool, b) angle tool.

Discussion

Principal Results and Comparison to Prior Work

Both the circumference and angle measuring tools of the ARPPS had an accuracy that was not significantly different as compared to the PACS measurements used in traditional preoperative settings. The circumference tool had an overall bias of 0.08%, which is more accurate than the 0.3% previously reported for a comparable AR system [30]. Similarly, the angle tool had an overall bias of –1.84%, which is more accurate than that previously reported for another 3D reconstruction software already on the market [31].

Interestingly, a decrease in percent error in either circumference or angle tool measurements was associated with an increase in the size of the object and ray length, respectively (Figure 6). This was consistent with a corresponding increase in the ease of manipulation of the hologram for larger objects as reported by both readers. AR and mixed reality–viewing hardware with higher resolution and responsiveness is likely to significantly improve the usability of such systems.

Limitations

Manipulating objects on the HoloLens can be technically challenging and contain a systematic error. Both readers reported difficulties in determining a clear vertex for angles A and C. However, angle B, which had no reported difficulties in measurement, showed a bias of only 0.14%. In addition, readers reported significant improvements in hologram manipulation dexterity with experience.

Conclusions

ARPPS can be an effective, precise, and accurate tool for the realistic visualization, manipulation, and measurement of clinically significant angles and circumferences in 3D space. ARPPS measurements are of substantially equivalent accuracy and precision as compared to standard-of-care PACS, similar systems that have previously been awarded the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance as class II medical devices for presurgical planning, and other systems with published data [30,31]. Nonetheless, technological difficulties remain a major barrier to the adoption of such technologies in medical and surgical care settings. To realize the full potential of AR and similar technologies, it is important that the medical community works in concert with device manufacturers to ensure the devices’ real-world feasibility, usability, safety, and efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We thank UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital for the use of their CT and computers for obtaining PACS measurements. In addition, we thank the Microsoft HoloLens team for providing research and technology support for the HoloLens and Dr Nancy Hills, Associate Professor of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco for the advice on our biostatistics methods and analyses.

Abbreviations

- 2D

2-dimensional

- AR

augmented reality

- ARPPS

augmented reality presurgical planning system

- CT

computed tomography

- DICOM

digital imaging and communications in medicine

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PACS

picture archiving and communication system

- VR

virtual reality

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: JC is an Associate Clinical Professor in Pediatric Radiology at the University of California, San Francisco and creator of the ARPPS but did not participate in the collection or analysis of the data.

References

- 1.Choplin RH, Boehme JM, Maynard CD. Picture archiving and communication systems: an overview. RadioGraphics. 1992 Jan;12(1):127–129. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.12.1.1734458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilson HT, Reddix RN, Mutty CE, Webb LX. The long lost art of preoperative planning--resurrected? Orthopedics. 2008 Dec;31(12) doi: 10.3928/01477447-20081201-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shamshuddin S, Matthews H. Use of OsiriX in developing a digital radiology teaching library. Clin Radiol. 2014 Oct;69(10):e373–80. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khor WS, Baker B, Amin K, Chan A, Patel K, Wong J. Augmented and virtual reality in surgery-the digital surgical environment: applications, limitations and legal pitfalls. Ann Transl Med. 2016 Dec;4(23):454. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.12.23. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.12.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dias CR, Pereira MR, Freire AP. Qualitative review of usability problems in health information systems for radiology. J Biomed Inform. 2017 Dec;76:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.10.004. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1532-0464(17)30223-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas B, Demczuk V, Piekarski W, Hepworth D, Gunther B. A wearable computer system with augmented reality to support terrestrial navigation. Second International Symposium on Wearable Computers; 1998; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. IEEE; 1998. Oct 19, [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunston PS, Wang X. Mixed Reality-Based Visualization Interfaces for Architecture, Engineering, and Construction Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 2005 Dec;131(12):1301–1309. doi: 10.1061/(asce)0733-9364(2005)131:12(1301). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hořejší P. Augmented Reality System for Virtual Training of Parts Assembly. Procedia Engineering. 2015;100:699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2015.01.422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fjeld M, Voegtli BM. Augmented Chemistry: an interactive educational workbench. International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality; 2002; Darmstadt, Germany. IEEE; 2002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogdon DC. HoloLens and VIVE Pro: Virtual Reality Headsets. J Med Libr Assoc. 2019 Jan 04;107(1):118–121. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2019.602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uppot RN, Laguna B, McCarthy CJ, De Novi G, Phelps A, Siegel E, Courtier J. Implementing Virtual and Augmented Reality Tools for Radiology Education and Training, Communication, and Clinical Care. Radiology. 2019 Jun;291(3):570–580. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019182210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komasawa N, Ohashi T, Take A, Doi Y, Kadoyama K, Terasaki F, Dote T, Akazawa C. Hybrid simulation training utilizing augmented reality and simulator for interprofessional advanced life support training. J Clin Anesth. 2019 Nov;57:106–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wellens LM, Meulstee J, van de Ven CP, Terwisscha van Scheltinga CEJ, Littooij AS, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Fiocco M, Rios AC, Maal T, Wijnen MHWA. Comparison of 3-Dimensional and Augmented Reality Kidney Models With Conventional Imaging Data in the Preoperative Assessment of Children With Wilms Tumors. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 05;2(4):e192633. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2633. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qian L, Deguet A, Kazanzides P. ARssist: augmented reality on a head-mounted display for the first assistant in robotic surgery. Healthc Technol Lett. 2018 Oct;5(5):194–200. doi: 10.1049/htl.2018.5065. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30800322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourdel N, Chauvet P, Calvet L, Magnin B, Bartoli A, Canis M. Use of Augmented Reality in Gynecologic Surgery to Visualize Adenomyomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(6):1177–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low D, Lee CK, Dip LLT, Ng WH, Ang BT, Ng I. Augmented reality neurosurgical planning and navigation for surgical excision of parasagittal, falcine and convexity meningiomas. Br J Neurosurg. 2010 Feb;24(1):69–74. doi: 10.3109/02688690903506093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato Y, Nakamoto M, Tamaki Y, Sasama T, Sakita I, Nakajima Y, Monden M, Tamura S. Image guidance of breast cancer surgery using 3-D ultrasound images and augmented reality visualization. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998 Oct;17(5):681–93. doi: 10.1109/42.736019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boillat T, Grantcharov P, Rivas H. Increasing Completion Rate and Benefits of Checklists: Prospective Evaluation of Surgical Safety Checklists With Smart Glasses. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Apr 29;7(4):e13447. doi: 10.2196/13447. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/4/e13447/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vávra P, Roman J, Zonča P, Ihnát P, Němec M, Kumar J, Habib N, El-Gendi A. Recent Development of Augmented Reality in Surgery: A Review. J Healthc Eng. 2017;2017:4574172. doi: 10.1155/2017/4574172. doi: 10.1155/2017/4574172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navab N, Blum T, Wang L, Okur A, Wendler T. First Deployments of Augmented Reality in Operating Rooms. Computer. 2012 Jul;45(7):48–55. doi: 10.1109/mc.2012.75. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang F, Laguna B, Uribe J, Vu Lan, Zapala Matthew A, Devincent Craig, Courtier Jesse. Evaluating the Performance of Augmented Reality in Displaying Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Derived Three-Dimensional Holographic Models. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2020 Mar;51(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alletto C. 510(k) Premarket Notification K101342 - PIXMEO SARL OSIRIX MD. FDA 510(k) Premarket Notification Database. 2010. [2019-06-01]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPMN/pmn.cfm?ID=K101342.

- 23.Dwivedi G, Mahadevan Ganadevan, Jimenez Donie, Frenneaux Michael, Steeds Richard P. Reference values for mitral and tricuspid annular dimensions using two-dimensional echocardiography. Echo Res Pract. 2014 Dec 01;1(2):43–50. doi: 10.1530/ERP-14-0050. https://erp.bioscientifica.com/doi/10.1530/ERP-14-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaikof EL, Dalman RL, Eskandari MK, Jackson BM, Lee WA, Mansour MA, Mastracci TM, Mell M, Murad MH, Nguyen LL, Oderich GS, Patel MS, Schermerhorn ML, Starnes BW. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2018 Jan;67(1):2–77.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.044. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0741-5214(17)32369-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horne J, Flannery R, Usman S. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Feb 01;89(3):193–198. doi: 10.5005/jp/books/12193_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chao E, Neluheni E V, Hsu R W, Paley D. Biomechanics of malalignment. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994 Jul;25(3):379–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soloman L. In: Apley's System of Orthopaedics and Fractures. Warwick D, Nayagam S, editors. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin LI. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989 Mar;45(1):255–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altman DG, Bland JM. Measurement in Medicine: The Analysis of Method Comparison Studies. The Statistician. 1983 Sep;32(3):307–317. doi: 10.2307/2987937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merrill D. 510(k) Premarket Notification K172418 - Novarad Opensight. FDA 510(k) Premarket Notification Database. 2018. [2019-06-01]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K172418.

- 31.Ilharreborde B, Steffen JS, Nectoux E, Vital JM, Mazda K, Skalli W, Obeid I. Angle Measurement Reproducibility Using EOSThree-Dimensional Reconstructions in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Treated by Posterior Instrumentation. Spine. 2011;36(20):E1306–E1313. doi: 10.1097/brs.0b013e3182293548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]