Abstract

Trait aggression has been studied for decades and yet remains adrift from broader frameworks of personality such as the Five Factor Model. Across two datasets from undergraduate participants (Study 1: N = 359; Study 2; N = 620), we observed strong manifest and latent correlations between trait aggression and lower agreeableness (i.e., greater antagonism). Trait aggression was also linked to greater neuroticism and lower conscientiousness, but their effect sizes fell beneath our preregistered threshold. Subsequent item-level analyses were unable to articulate trait aggression and agreeableness items into separate factors using the IPIP-NEO, but not the Big Five Inventory. Our findings suggest that trait aggression is accurately characterized as primarily a facet of antagonism, while also reflecting other personality dimensions.

Keywords: trait aggression, antagonism, agreeableness, Five Factor Model, personality

1. Introduction

Some people are more aggressive than others. This basic individual difference is a critically important topic of research, as assessments of dispositional aggression predict real-world acts of violence across the lifespan (Huesmann, Eron, Lefkowitz, & Walder, 1984). The scientific study of such ‘trait aggression’ has grown substantially with 422 papers published on the topic in 2019 alone (via Google Scholar). Commensurate with that growth have been criticisms of the construct’s various definitions and other areas of theoretical ambiguity (e.g., Paulhus, Curtis, & Jones, 2018). Indeed, trait aggression suffers from not being situated within a broader theoretical framework of personality. Being thus adrift from larger taxonomies of personality has real consequences for personality constructs, as it leaves the construct poorly defined in both the characteristics that do and do not comprise the construct, as well as its relation to other constructs (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). To attempt to find a theoretical home for trait aggression within the Five Factor Model of personality (Digman, 1990; John & Srivastava, 1999), we analyzed data from over 900 participants to examine whether trait aggression can be accurately characterized as a facet of antagonism.

2. Trait Aggression: Definition and the Buss-Perry Model

Aggression refers to any attempt to harm someone against their will (Allen & Anderson, 2017). Trait aggression, broadly defined, is the dispositional tendency toward such aggressive behavior across situations and over time (Chester & DeWall, 2013). The specific tendencies that comprise trait aggression are an area of considerable theoretical debate. A popular model was advanced by Buss and Perry (1992), in which trait aggression was comprised of tendencies towards physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility. Trait physical and verbal aggression reflect the behavioral components of trait aggression, capturing tendencies towards perpetrating overt acts of harm-doing. Trait anger is the affective component of trait aggression, and is defined as the tendency to experience greater feelings of anger and impairment in regulating the behavioral expression of those angry feelings. Trait hostility is the cognitive component of trait aggression and entails cynical and suspicious cognitive biases towards others, who are viewed as threats to the self. According to the Buss-Perry four factor model, these four factors can be aggregated to reflect the overall construct of trait aggression.

This four factor model was based on the results of factor analyses of items that were either newly-created or modified from previous personality and clinical inventories and then administered to undergraduate students in the United States (Buss & Perry, 1992). The resulting Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire’s four factor structure has been replicated in violent clinical (e.g., Diamond, Wang, & Buffington-Vollum, 2005) and forensic (e.g., Gallagher & Ashford, 2016) samples, as well as across different cultures and languages (e.g., Ando et al., 1999; García-León et al., 2002; Gerevich, Bácskai, & Czobor, 2007). Other approaches to trait aggression emphasize tendencies towards reactive and proactive aggression (Raine et al., 2006), as well as overt and relational aggression (Marsee et al., 2011), inter alia. The proliferation of these models reflects the complexity of trait aggression and a desperate need for theoretical coherence. Yet, among these varied approaches to trait aggression, the Buss-Perry (1992) four facet model has emerged as the most widely used and accepted approach (cited in Google Scholar 6,771 times as of May 13th, 2020).

Despite being such a widely-adopted measure of trait aggression, much of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire’s item content assesses psychological phenomena that do not fall within the accepted definition of aggression (Allen & Anderson, 2017; Buss & Perry, 1992). Most evidently, the Anger and Hostility subscales refer to affective and cognitive processes, whereas aggression refers only to behavior. For investigators interested in measuring canonically-defined aggression, the Physical and/or Verbal Aggression subscales should be used instead of the total score of this measure (e.g., Chester, Lynam, Milich, & DeWall, 2018). Thus, trait aggression as measured by this questionnaire is a construct with borders that extend well beyond ‘pure’ aggression into nearby domains. Whether the broader approach to measuring trait aggression across these four factors is a valid practice is open to debate, though this debate is beyond the scope of the present research.

3. Theoretical Ambiguity Surrounding Trait Aggression

Though much research has been done with trait aggression, relatively few attempts have been made to situation this construct in a broader theory of personality. Personality constructs are best construed hierarchically, with lower-level traits comprising mid-level trait facets that comprise higher order factors of trait constellations (Goldman, 2006). However, it is unclear where trait aggression accurately resides in such a hierarchical taxonomy, leaving the fundamental nature of this construct ambiguous. Though multiple studies have examined correlations between trait aggression and the Five Factor Model (e.g., Bettencourt, Talley, Benjamin, & Valentine, 2006; Sharpe & Desai, 2001; Tremblay & Ewart, 2005), no studies to our knowledge have gone beyond estimating these manifest-level associations to test the appropriateness of nesting trait aggression within this broader framework.

Such theoretical ambiguity around trait aggression is consequential. Indeed, some scholars have suggested that the ambiguity surrounding trait aggression’s definition and relation to other constructs and theories warrants its elimination as a personality construct altogether, suggesting it should only be conceptualized and investigated as a behavioral outcome (Paulhus et al., 2018). Thus, the consequences of a lack of theoretical scaffolding around trait aggression are clear and must be articulated lest this construct be eliminated from the literature. Yet in which theoretical framework is trait aggression best situated?

4. Trait Aggression and the Five Factor Model

The number of variables that have been reliably associated with trait aggression is too vast to summarize here. However, one of the most reliable correlates of trait aggression are aspects of the Five Factor Model (Bettencourt et al., 2006; Sharpe & Desai, 2001; Tremblay & Ewart, 2005). The Five Factor Model of personality proposes that the vast corpus of lower-level human traits is parsimoniously, accurately, and reliably characterized by five higher-order factors: agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness to experience (Digman, 1990; John & Srivastava, 1999). Among the five factors, trait aggression has been strongly and reliably linked to lower agreeableness and greater neuroticism (Bettencourt et al., 2006; Dunne, Gilbert, & Daffern, 2018). When the facets of trait aggression were examined individually, neuroticism’s associations were strongest for anger and hostility, whereas low agreeableness explained more variance in physical and verbal aggression (Tremblay & Ewart, 2005). Given that aggression is defined as a behavior, and not angry feelings or hostile cognitive biases (Allen & Anderson, 2017), then it is best captured by the trait physical and verbal aggression subscales. As such, low agreeableness appears to lie at the heart of trait aggression.

5. Trait Aggression and Antagonism

Each aspect of the Five Factor Model can be construed as a continuum in which high levels reflect the presence of more of the named construct (e.g., high agreeableness scores reflect the presence of relatively more agreeable traits in a person; Digman, 1990; John & Srivastava, 1999). However, the lower end of each factor’s continuum does not simply reflect an absence of that construct. For instance, a low agreeableness score does not simply reflect an absence of agreeable traits. Instead, low agreeableness scores reflect the presence of antagonistic traits (Lynam, & Miller, 2019). Whereas agreeableness reflects a compassionate, moral, modest, affable, and trusting orientation towards others, antagonism is characterized by a callous, immoral, arrogant, combative, and distrustful approach to social interactions. These thematic elements of antagonism render it clear why this trait dimension is so robustly correlated with trait aggression. Indeed, aggression often entails a callous response to the victim’s suffering (Frick & White, 2008), is broadly perceived as immoral (Reeder, Kumar, Hesson-McInnis, & Trafimow, 2002), is most often perpetrated by those with grandiose self-concepts (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998) and hostile interpersonal styles that emphasize distrust of others (Dodge, Price, Bachorowski, & Newman, 1990). The neat conceptual fit and robust empirical association between trait aggression and antagonism suggest that trait aggression might be best theoretically characterized within the Five Factor Model, as a lower-level facet of the higher-order antagonism factor.

Although antagonism may seem to many scholars like the logical place of residence for trait aggression, there are empirical findings and dominant perspectives in the aggression literature that would make claims to the contrary. Analyses that distilled various agreeableness and antagonism measures into a single, consensus-based set of facets did not identify an aggression facet (Crowe, Lynam, & Miller, 2018; Lynam & Miller, 2019). This inability to uncover aggression as a facet of antagonism may reflect psychology’s emphasis on aggression as a behavioral outcome and not a personality trait, which may have excluded much aggression-related content from the field’s most widely used personality assessment tools. In addition, much of the earliest work on the psychology of aggression emphasized the important role of heightened and dysregulated negative affect (e.g., the frustration-aggression hypothesis: Berkowitz, 1989). This framework would advance heightened neuroticism as the conceptual home for trait aggression. Other scholars have focused on the critical role of impaired self-control in causing aggressive and antisocial behaviors (e.g., Denson, DeWall, & Finkel, 2012; the general theory of crime: Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990), who would then place trait aggression under the theoretical umbrella of low conscientiousness. As such, it has remained an open question regarding which of the Five Factors was best to couch trait aggression underneath.

6. The Present Research

If antagonism lies at the core of trait aggression, then the latent construct of trait antagonism should explains the overwhelming majority of the variance in the latent construct of trait aggression (see Vize, Collison, Miller, & Lynam, 2020). Correlations between manifest variables obscure these latent associations because they include the measurement error inherent to each questionnaire. Latent correlations estimated between latent factors in structural equation modeling eliminate the influence of such measurement error and examine how much variance is explained between two latent constructs (Nunnally, 1994).

Following a preregistered series of two plans (https://osf.io/73ngb/registrations), we applied this latent correlation approach to test the prediction that a latent antagonism factor would explain the overwhelming majority of the variance in a latent trait aggression factor (i.e., latent correlations > |.60|; the threshold used by Vize et al., 2020). We examined these latent associations across two datasets, which employed different Five Factor Model (FFM throughout Method and Result sections) measures alongside the same measure of trait aggression. The de-identified data and analysis code that are necessary to replicate our results are publicly available here: https://osf.io/73ngb/files/.

7. Method

7.1. Participants

Participants were undergraduate students recruited through psychology subject pools (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, by Study

| Study | N | % Females | % Males | Age M | Age SD | Age Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 359 | 69.64 | 30.36 | 18.65 | 0.98 | 18–26 |

| 2 | 620 | 71.10 | 28.90 | 19.03 | 1.89 | 18–41 |

7.2. Materials

7.2.1. Big Five Inventory (Study 2).

The 44-item Big Five Inventory (BFI) measures each FFM factor with a subscale: agreeableness (9 items), conscientiousness (9 items), extraversion (8 items), neuroticism (8 items), and openness to experience (10 items; John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991; John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008; John & Srivastava, 1999). For each item, participants rated their agreement with self-descriptive statements (e.g., “is reserved”, “can be tense”) using a 1 (Disagree Strongly) to 5 (Agree Strongly) response scale.

7.2.2. Brief Aggression Questionnaire.

In both studies, trait aggression was assessed via the 12-item Brief Aggression Questionnaire (BAQ: Webster et al., 2014). The BAQ was created by identifying the three highest-loading items from each subscale of the larger Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992). The BAQ includes four subscales: physical aggression (sample item: “Given enough provocation, I may hit another person”), verbal aggression (sample item: “My friends say that I’m somewhat argumentative”), anger (sample item: “I have trouble controlling my temper”), and hostility (sample item: “I sometimes feel that people are laughing at me behind my back”). Participants rated the extent to which various self-descriptive statements accurately characterized them from 1 (Study 1: strongly disagree; Study 2: extremely uncharacteristic of me) to 7 (Study 1: strongly agree; Study 2: extremely characteristic of me).

7.2.3. IPIP-NEO (Study 1).

The 120-item International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) representation of the NEO Personality Inventory (IPIP-NEO) measures each FFM factor with a 24-item subscale: agreeableness (sample item: “I sympathize with the homeless”), conscientiousness (sample item: “I like order”), extraversion (sample item: “I love large parties”), neuroticism (sample item: “I get irritated easily.”), and openness to experience (sample item: “I prefer variety to routine”; Goldberg, 1999; Goldberg et al., 2006). Each of the five factor subscales can be further divided into six facet-level subscales (four items per facet subscale). For each item, participants rated their agreement with various self-descriptive statements using a 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly) response scale.

7.3. Procedure

In Study 1, participants arrived at the laboratory alone or in groups of two to four. Participants were randomly assigned to be socially included or excluded via the Cyberball paradigm (version 4.0; Williams, Cheung, & Choi, 2000), as Study 1 was a larger project on the interactive roles between personality and experimentally-induced negative affect (Chester, Lynam, Milich, & DeWall, 2017). Participants then completed a battery of computerized self-regulatory behavioral tasks (e.g., a Go/No-Go Task), followed by a battery of computerized personality questionnaires that included the BAQ and the IPIP-NEO. Participants were then debriefed and dismissed.

In Study 2, participants arrived at the laboratory alone or in groups of two to four. Participants either consumed pill capsules that contained 1000mg of acetaminophen, consumed pill capsules that contained a corn starch placebo (which participants were blind to throughout the study), or consumed no pill capsules at all, as part of a broader project on the role of reduced physical pain in decision-making and personality (e.g., DeWall, Chester, & White, 2015). To occupy participants while the drug became psychoactive (which takes approximately 45 minutes after pill consumption), participants completed a computerized battery of personality questionnaires that included the full Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (from which the BAQ was derived) and the BFI. Participants then completed a battery of decision-making tasks and were then debriefed and dismissed.

7.4. Data Analyses

7.4.1. Latent correlation analyses.

We conducted a series of preregistered latent factor analyses using the lavaan (version 0.6; Rosseel, 2012) package for R statistical software (version 3.2.1; R Core Team, 2019). These models estimated the latent correlations between a latent ‘trait aggression’ factor and each latent factor of the Five Factor Model. These analyses handled missing data with full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. Error terms of each indicator were left uncorrelated, yet these models did estimate latent correlations between each latent factor. To set the scale of each latent factor, the first indicator of each factor was fixed to one. Across both studies, a latent ‘trait aggression’ factor was modeled as the shared variance between the four trait aggression subscales (i.e., anger, hostility, physical aggression, verbal aggression). For Study 1, each of the latent Five Factor Model factors were indicated by that factor’s six facet-level subscales. In Study 2, each of the BFI’s five latent factors reflected two facet-level subscales that were identified by Soto and John (2009).

7.4.2. Hierarchical exploratory factor analyses (EFA).

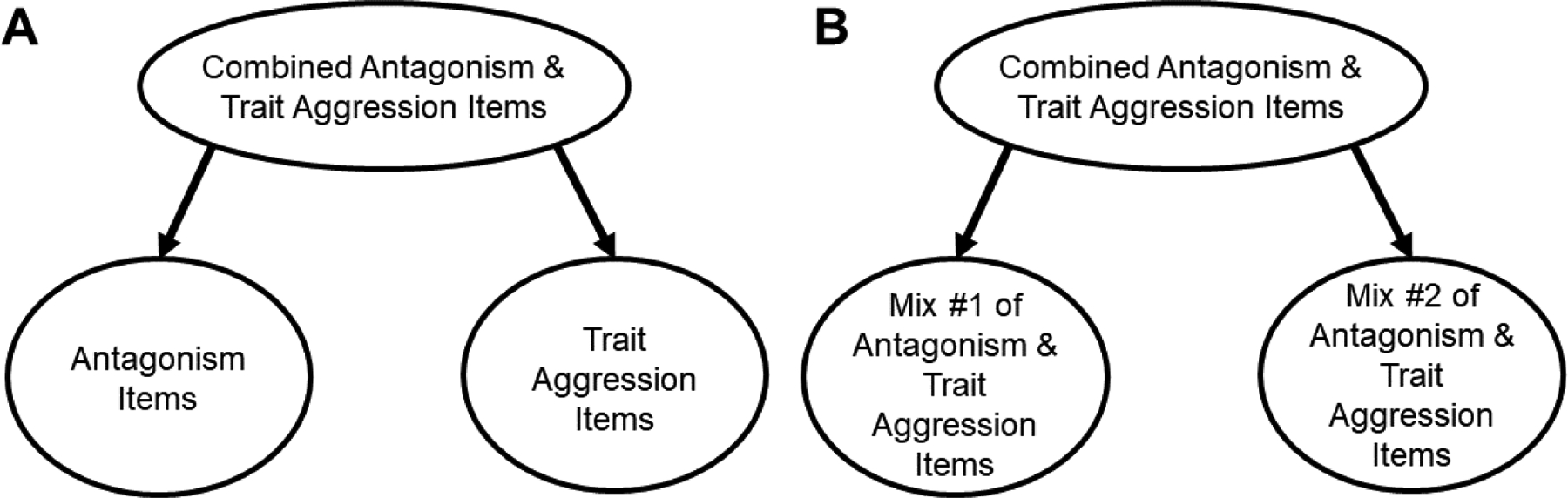

Another statistical approach that examines the extent to which two constructs are either distinct from each other or truly enmeshed is factor analyses. To examine whether such analyses could extract distinct ‘trait aggression’ and ‘antagonism’ factors from a dataset that combined items that measure both constructs, we ran a series of non-preregistered, hierarchical EFAs for each study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of our Hierarchical Exploratory Factor Analysis Approach That Tested Whether a Combined Dataset of Trait Aggression and Agreeableness Items Would Either Produce (A) Distinct Factors for Each Construct; or (B) Inter-Mixed Factors That Included Items From Both Constructs.

First, we combined and standardized trait aggression items from the Brief Aggression Questionnaire and agreeableness items via the RobustHD package for R (version 0.6.1; Alfons, 2019). Then, we used R’s psych package (version 1.9.12; Revelle, 2019) to impute missing data with the corresponding item’s mean, as item-mean imputation reduces bias introduced into the analyses by the alternative approach of simply excluding those datapoints. Finally, we conduct hierarchical EFAs, which were hierarchical in the sense that we used principal axis factoring to first extract a single, un-rotated factor and then extracted two factors from the same dataset via promax rotation (as in Crowe et al., 2018). A factor loading cutoff of |.40| was employed to delineate which items loaded onto which factors. Items that loaded onto more than one factor were excluded from each factor solution.

8. Results

8.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics are provided in Supplemental Table 1. Missing data rates were minimal for all variables (i.e., < 10% missingness). Across both studies, most measures exhibited adequate internal consistency (i.e., ω >/= .70), excepting 20 of the 48 facet-level subscales that exhibited ω values between .60 and .69, as well as the Compliance facet of the BFI’s Agreeableness subscale in which ω = .52. Suggesting that the social exclusion manipulation from Study 1 did not exert a substantive effect on trait reports, only the Imagination facet-level subscale of the IPIP-NEO exhibited any significant difference between the Cyberball manipulation’s excluded and included conditions (Supplemental Table 2).

8.2. Zero-Order Correlations (Exploratory)

Across both studies, we found that higher trait aggression was most associated with lower agreeableness (Table 2). Higher trait aggression was also linked, though to a lesser extent, with greater neuroticism and lower conscientiousness in both studies. These correlations revealed substantial differences between the IPIP-NEO and BFI in how their remaining FFM factors related to trait aggression. Indeed, trait aggression was unassociated with extraversion and openness using the IPIP-NEO and positively associated with these two factors using the BFI. Similarly, agreeableness was unassociated with neuroticism using the IPIP-NEO and positively associated with neuroticism using the BFI. This suggests that BFI-measured agreeableness included more neuroticism-related content that was absent from the IPIP-NEO’s agreeableness subscale.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations Between Manifest Study Variables, by Study

| Study | FFM Measure | BAQ | A | C | E | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IPIP-NEO - Agreeableness | −.51*** | ||||

| IPIP-NEO - Conscientiousness | −.26*** | .25*** | ||||

| IPIP-NEO - Extraversion | .06 | .05 | .31*** | |||

| IPIP-NEO - Neuroticism | .18** | −.02 | −.47*** | −.43*** | ||

| IPIP-NEO - Openness | .05 | .21*** | −.10 | .07 | .03 | |

| 2 | BFI - Agreeableness | −.44*** | ||||

| BFI - Conscientiousness | −.26*** | .31*** | ||||

| BFI - Extraversion | .11** | .12** | .07 | |||

| BFI - Neuroticism | .27*** | −.28*** | −.14*** | −.18*** | ||

| BFI - Openness | .14*** | .03 | .03 | .21*** | −.11** |

Note. BAQ = Brief Aggression Questionnaire, FFM = Five Factor Model, BFI = Big Five Inventory, IPIP-NEO = International Personality Item Pool’s representation of the NEO Personality Inventory. A = agreeableness, C = conscientiousness, E = extraversion, N = neuroticism.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Zero-order correlations between the BAQ total score and each of the facet-level subscales of the IPIP-NEO (Study 1) and BFI (Study 2) are depicted in Supplemental Figures 1 and 2, respectively. In Study 1, these correlations suggested that trait aggression most strongly reflected lower levels of the Cooperation (r = −.60) and Morality (r = −.33) facets of Agreeableness, and greater levels of the Anger facet of Neuroticism (r = .48). In Study 2, trait aggression was most linked to lower levels of the Compliance facet of Agreeableness (r = −.44) and greater levels of the Depression facet of Neuroticism (r = .39).

8.3. Relative Importance Analyses (Exploratory)

To examine whether the manifest, zero-order correlations between trait aggression and agreeableness were meaningfully larger than the correlations with neuroticism and conscientiousness, we employed correlation comparison and dominance analyses. First, we used an online utility to compare the size of correlations in an exploratory fashion (Lee & Preacher, 2013), which revealed that the absolute value of agreeableness’ association with trait aggression was indeed larger than the absolute correlation between trait aggression and neuroticism, Study 1: Z = 4.70, p < .001; Study 2: Z = 2.98, p = .003, or conscientiousness, Study 1: Z = 4.19, p < .001; Study 2: Z = 4.20, p < .001.

We next conducted dominance analyses, which examined the amount of variance in trait aggression that was explained by an aggregated estimate of all possible combinations of the FFM factors (Budescu, 1993; Kraha, Turner, Nimon, Zientek, & Henson, 2012), using the yhat package for R (version 2.0; Nimon, Oswald, & Roberts, 2013). Across both studies, agreeableness exhibited much larger general dominance weights (i.e., the variable’s aggregated semi-partial correlation contributions to model R2, above-and-beyond all other predictors and permutations thereof; Table 3).

Table 3.

General Dominance Weights Representing Each FFM Factor’s Relative Ability to Explain Variance in Trait Aggression, by Study

| Study | A | C | E | N | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .25 | .03 | .02 | .03 | .01 |

| 2 | .15 | .04 | .02 | .05 | .02 |

Note. FFM = Five Factor Model. A = agreeableness, C = conscientiousness, E = extraversion, N = neuroticism, O = openness to experience.

8.4. Latent Correlations (Preregistered and Confirmatory)

At the latent level, the association between trait aggression and agreeableness was negative and strong to the point of redundancy in Study 1 (Table 4). We also observed latent correlations between greater trait aggression and greater neuroticism across both studies. In Study 2, this latent correlation with neuroticism was just beneath our preregistered threshold, though this effect was much smaller in Study 1. We also observed a strong, negative correlation between trait aggression and conscientiousness in both studies and null effects for extraversion and openness.

Table 4.

Latent Correlations Between Trait Aggression and Agreeableness, by Study

| Study | FFM Measure | A | C | E | N | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IPIP-NEO | −.90** | −.29** | −.01 | .22* | −.03 |

| 2 | BFI | −.67*** | −.36** | .01 | .59*** | .10 |

Note. BFI = Big Five Inventory, FFM = Five Factor Model, IPIP-NEO = International Personality Item Pool’s representation of the NEO Personality Inventory. A = agreeableness, C = conscientiousness, E = extraversion, N = neuroticism, O = openness to experience.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Factor loadings (presented in Supplemental Table 3), indicated that the latent agreeableness factor mostly reflected the Cooperation, Modesty, and Morality facets of the IPIP-NEO’s agreeableness construct. In Study 2, the aggression- agreeableness latent correlation was still strongly negative, but not to the point of redundancy. This latent agreeableness factor similarly reflected both of this construct’s facet-level subscales (Supplemental Table 3).

8.5. Hierarchical Factor Analyses (Exploratory)

8.5.1. One factor EFA.

Across both studies, one-factor EFAs produced single-factors that included both trait aggression and agreeableness items (Supplemental Table 4). These factors explained 15.86% of the variance in Study 1 and 24.06% of the variance in Study 2.

8.5.2. Two factor EFA.

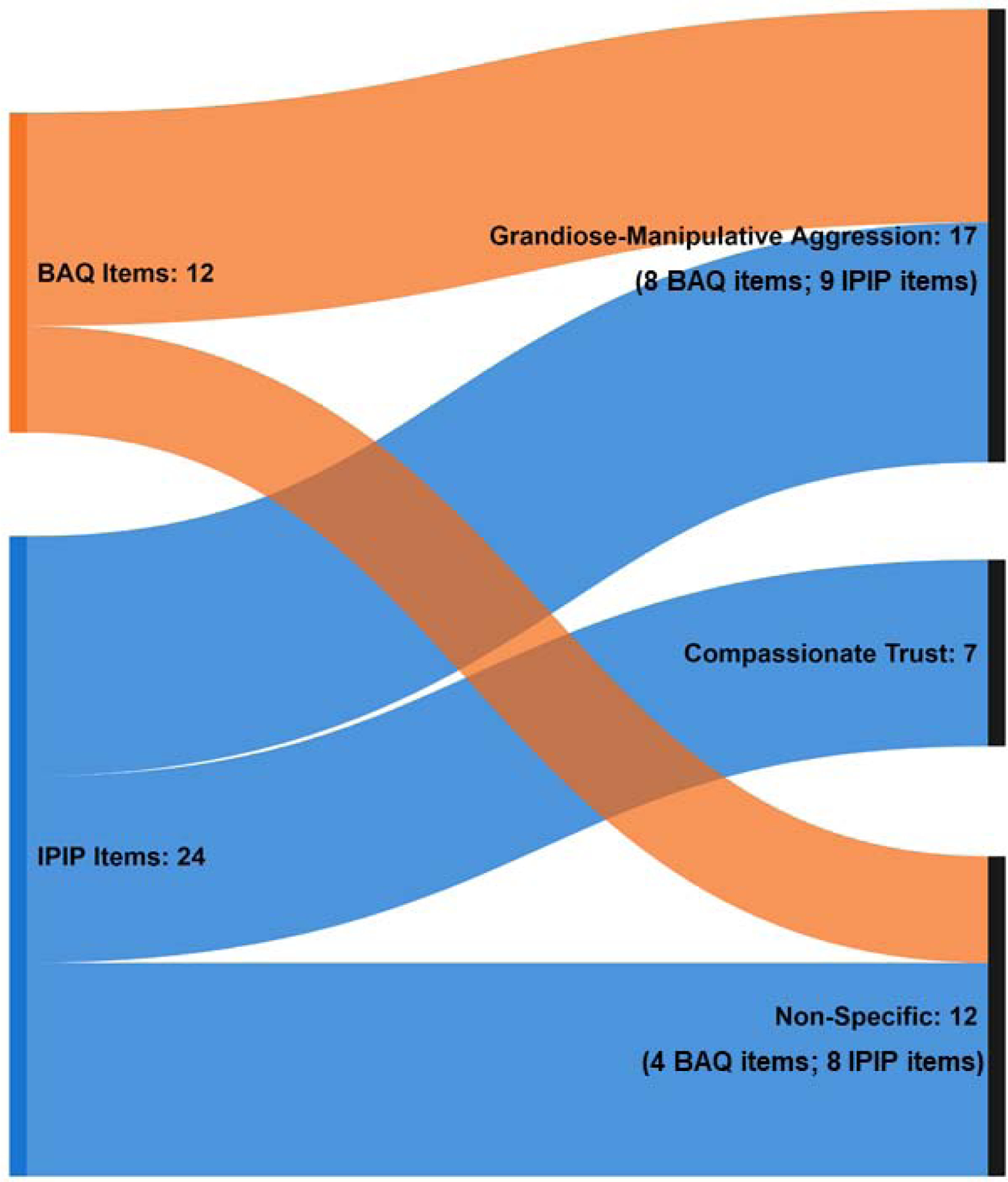

In Study 1, the two-factor EFA did not extract distinct factors for trait aggression and agreeableness. Instead, the EFA revealed an initial factor that included trait aggression and agreeableness items mixed in with each other (Figure 2; Supplemental Table 5). The first factor in Study 1 explained 14.14% of the variance and was comprised of eight trait aggression and nine agreeableness items. A content analysis of this initial factor suggested that it was best described as representing ‘grandiose-manipulative aggression’, as the highest loading items pertained to overt acts of aggressive behavior (examples: “I love a good fight”, “Given enough provocation, I may hit another person”) and the remaining items pertained to grandiose self-views (examples: “I believe that I am better than others”, “I make myself the center of attention”) and manipulative behavior (examples: “I know how to get around the rules”, “I use flattery to get ahead”). Given the centrality of grandiose-manipulative traits to psychopathy, one might also term this factor ‘psychopathic aggression’. Study 1’s second factor explained 9.30% of the variance and was comprised of seven IPIP-NEO agreeableness items. A content analysis of this second factor suggested that it was best described as representing ‘compassionate trust’, as the highest loading items pertained to trust towards others (examples: “I believe that others have good intentions”, “I trust what people say”) and the remaining items pertained to compassionate concern for others (examples: “I love to help others”, “I am concerned about others”).

Figure 2.

Alluvial Plot From Study 1 Depicting the Flow of Items From the BAQ (in Orange) and the IPIP-NEO’s Agreeableness Subscale (in Blue) Into a Mixed ‘Grandiose-Manipulative Aggression’ Factor and an IPIP-Specific ‘Compassionate Trust’ Factor --- as Well as ‘Non-Specific’ Items That Failed to Load Onto Either of the Two Factors.

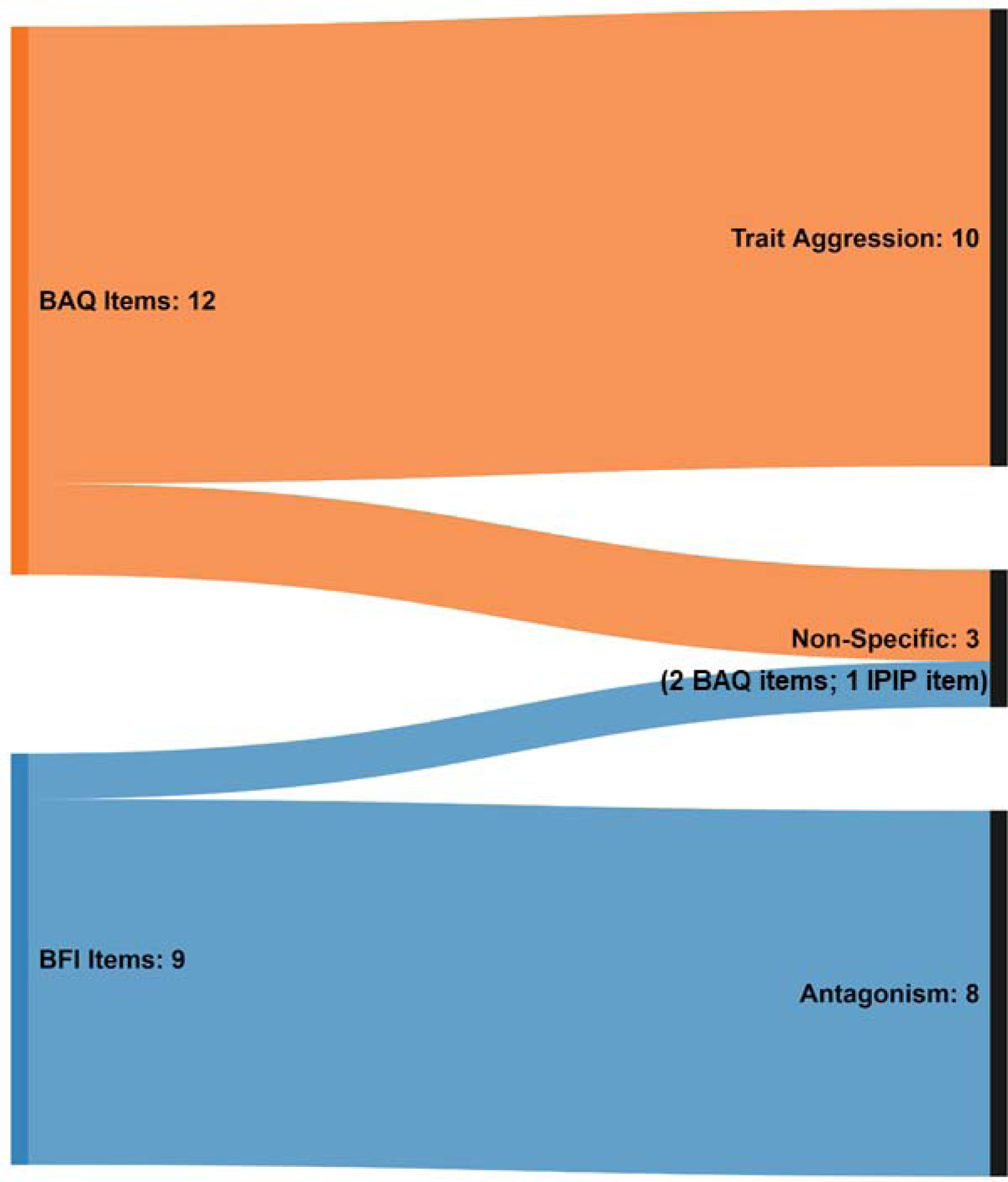

Study 2 did not replicate the inter-mixed factor compositions from Study 1 (Figure 3). Indeed, the two-factor EFA from Study 2 returned an initial ‘trait aggression’ factor that explained 15.75% of the variance and exclusively included BAQ items. The EFA revealed a second ‘antagonism’ factor that explained 13.80% of the variance and exclusively included BFI items (Supplemental Table 5).

Figure 3.

Alluvial Plot From Study 2 Depicting the Flow of Items From the BAQ (in Orange) and the BFI’s Agreeableness subscale (in Blue) Into Two Distinct ‘Trait Aggression’ and ‘Antagonism’ Factors --- as Well as ‘Non-Specific’ Items That Failed to Load Onto Either of the Two Factors.

9. Discussion

People differ in many ways. One of those individual differences is trait aggression (i.e., how aggressive some people are across time and different situations; Chester & DeWall, 2013). Despite hundreds of studies demonstrating the important role of this construct, its theoretical foundations remain poorly articulated. In the present research we tested whether trait aggression exhibited evidence of existing as a facet of the Five Factor Model’s agreeableness-antagonism dimension.

9.1. Trait Aggression as a Facet of Antagonism

Across both studies, we observed latent correlations between trait aggression and antagonism that surpassed our preregistered threshold, indicating that a substantial proportion of the variance in trait aggression was explained trait antagonism. These associations were strong enough in Study 1 to suggest that these two constructs are empirically redundant with one another. No other factor of the Five Factor Model exhibited such robust associations with trait aggression. These findings buttress our claim that trait aggression primarily exists as a facet of the broader antagonism factor and therefore resides within the theoretical framework of the Five Factor Model of personality. Additionally, these findings support the growing notion that antagonism is the most robust correlate of aggressive, antisocial, and malevolent tendencies (Lynam & Miller, 2019; Vize et al., 2020).

We do not expand our argument to imply that trait aggression can be fully and exclusively encapsulated by trait antagonism. In line with the finding that most facet-level traits reflect a blend of the Five Factor Model’s broader dimensions (Schwaba, Rhemtulla, Hopwood, & Bleidorn, 2020), much of the manifest and latent variance in trait aggression is also explained by greater neuroticism and lower conscientiousness. Our findings with these other constructs mesh well with a host of prior work demonstrating robust associations between trait aggression and greater neuroticism and lower conscientiousness (Schwaba et al., 2020; Vize et al., 2018). Yet the extent of the aggression-antagonism associations we observed suggest that trait aggression can be primarily nested within antagonism (and is thus a lower-order facet thereof) and cannot be primarily nested within other dimensions of the Five Factor Model. Though researchers should consider all Five Factor Model constructs when discussing the broader personality basis of trait aggression, trait aggression could survive as a veridical (though deeply altered) construct without its neuroticism or conscientiousness content. Conversely, trait aggression would be mortally wounded without the variance it shares with antagonism.

The large difference between the size of the manifest and latent correlations we observed suggest that the latent correlation approach is a useful tool in determining the broader trait dimensions that subsume individual traits. The factor loadings from this analysis further revealed that the latent Agreeableness factor from Study 1 disproportionately reflected its own facets of Cooperation, Modesty, and Morality --- whereas the Agreeableness factor from Study 2 reflected similar influences from both of its constituent facets. It may be that Study 1’s differences between the zero-order and latent correlations, as well as the differences between our findings from Study 1 and Study 2, reflect the inflated influence of these specific facets and the lack of influence of other facets. However, the results of our latent correlation analyses meshed well with the results of our dominance and hierarchical factor analyses, which converged to tell a coherent story about the considerable overlap between trait aggression and agreeableness. Because these other analyses were not biased in terms of these three facets of agreeableness, it is unlikely that our findings from Study 1 are an artifact of their greater influence on the latent agreeableness factor.

9.2. Extracting Factors With Inter-Mixed Antagonism and Trait Aggression Items

Exploratory factor analyses revealed that for Study 1, trait aggression and antagonism items, once inter-mixed, could not be clearly extracted from one another. This indicates that the data did not respect the conceptual boundaries drawn between these two constructs and lends further evidence for trait aggression’s membership in the lower-order facets of antagonism. This finding did not replicate in the factor analysis from Study 2, which was able to re-articulate these two constructs when factor analyses were instructed to identify two factors. In combination with the markedly lower latent correlations obtained in Study 2, these findings suggest that there was a meaningful difference between the IPIP-NEO’s and the BFI’s ability to capture trait aggression.

9.3. Discrepancies Between Big Five and NEO Approaches to the Five Factor Model

A reason for the different results we observed between Studies 1 and 2 might come from research demonstrating that the Big Five and NEO measurement approaches capture different swaths of antagonism. Indeed, the BFI does not include content relevant to the honesty and humility facets of agreeableness, whereas such content is included in the items of NEO measures (Miller, Gaughan, Maples, & Price, 2011). Meta-analytic evidence suggests that dishonesty is particularly linked to aggression, whereas a lack of humility is more strongly linked to other antagonistic tendencies (Vize et al., 2018). The reduced amount of evidence we obtained for our hypotheses in Study 2 (which employed the BFI) meshes well with these meta-analytic results and suggests that dishonesty is likely to be one of the most crucial facet-level contributors to antagonism’s ability to encapsulate trait aggression. Future work is needed to examine why these specific antagonistic traits are able to characterize trait aggression so well.

Trait aggression’s latent link to neuroticism was almost as strong as agreeableness’ association in Study 2, which used the Big Five Inventory. Yet in Study 1, which employed the IPIP-NEO, this latent correlation was much weaker. As such, it appears that neuroticism’s link to trait aggression is contingent on whether a Big Five or NEO measurement approach is used. This pattern of results is hard to understand as the IPIP-NEO explicitly includes an ‘Anger’ facet and the BFI only includes facets for ‘Anxiety’ and ‘Depression’ and has no anger-related neuroticism content. It may be that by excluding the anger content that is redundant between neuroticism and trait aggression, the BFI is able to capture more variance in trait aggression. This possibility requires more investigation, as does the broader effect of including or excluding trait anger content upon neuroticism’s relations with trait aggression.

Trait anger represents an area of potential confusion in the Five Factor Model’s relationship with trait aggression, as trait anger rightly resides within the broader domains of both antagonism and neuroticism. This conceptual overlap may not be due to methodological or conceptual problems, yet it may instead reflect the possibility that anger is accurately conceptualized as a psychological impulse towards aggression (Veenstra, Bushman, & Koole, 2018). This fits with broader, functional accounts of emotions, which aver that emotions chiefly serve to ready organisms for specific behavioral actions (Hommel, Moors, Sander, & Deonna, 2017). In this way, the qualia and regulation of angry feelings ‘belong’ to the neuroticism domain and impulses towards aggression and other antisocial acts ‘belong’ to the antagonism domain. Because questionnaire items do not disambiguate these aspects, anger will exhibit a considerable amount of shared variance between antagonism and neuroticism. Importantly, not all aggression is motivated by anger and a considerable amount of trait aggression may reflect callous, unemotional tendencies towards harming others for instrumental reasons (Marsee et al., 2011) or appetitive tendencies towards rewarding aggression (Chester, 2017). Much more research is needed into detailing how trait anger is best articulated among antagonism, neuroticism, and trait aggression.

9.4. The Dark Tetrad Approach

Some scholars have called for the elimination of trait aggression from models of human personality, arguing instead that the Dark Tetrad should occupy its place (Paulhus et al., 2018). The Dark Tetrad refers to four antisocial personality constructs: psychopathy, Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Sadism. These four constructs do exhibit robust and reliable correlations with aggression (Chester, DeWall, & Enjaian, 2019; Jones & Neria, 2015). The shared variance between Dark Tetrad constructs is largely explained by antagonism, though they still retain important contributions from other Five Factor Model domains that help distinguish among these four facets (Vize et al., 2020). As such, the Dark Tetrad are primarily facets of antagonism that also reflect other trait dimensions, instead of distinct personality dimensions. Consequently, the Dark Tetrad’s ability to explain variance in trait aggression may simply replicate our conclusion that antagonism is the broader personality factor in which trait aggression conceptually resides.

9.5. Limitations on Generality and Future Directions

Perhaps our greatest limitation is that our sample was primarily composed of female undergraduates. However, our trait aggression measure exhibits evidence of measurement invariance across men and women (Bryant & Smith, 2001). Though mean levels of trait aggression would surely be higher among males (Buss & Perry, 1992), the underlying covariances between individual items and scales would be unchanged if the gender composition of each sample was altered. In addition to potential issues surrounding the gender composition of our sample, it remains unclear if our results would be different if we recruited a more violent population (e.g., individuals convicted of violent crimes) or conducted our study in a different culture. Yet the Buss-Perry four facet model of trait aggression replicates remarkably well in a broad array of samples (e.g., Ando et al., 1999; Diamond et al., 2005; Gallagher & Ashford, 2016; García-León et al., 2002; Gerevich et al., 2007), suggesting that our findings would generalize outside of undergraduates and the United States.

There are also several important limitations to the Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992) we used. First, the scale tends to disproportionately capture reactive (versus proactive) aggression (sample item: “There are people who pushed me so far that we came to blows”) --- and reactive aggression exhibits stronger links to neuroticism than proactive aggression (Vize, Miller, & Lynam, 2018). As such, our associations with neuroticism might be attenuated if we used a trait aggression measure that was more inclusive of proactive forms of aggression. Second, much of the Verbal Aggression subscale includes behaviors whose aggressive content is ambiguous and includes acts that may not be intentionally harmful and could be intended as affiliative (e.g., ‘My friends say that I’m somewhat argumentative’, ‘I tell my friends openly when I disagree with them’). As such, it is unclear if this subscale is accurately capturing verbal aggression and not a general interpersonal style that may not entail harmful intentions. Future research should seek to replicate our findings with verbal aggression measures that clearly include harmful intent.

The Buss and Perry (1992) approach to trait aggression also quantifies this construct using items that capture behavioral outcomes (sample item: “I get into fights a little more than the average person”). It may be inappropriate for such personality measures to include content that captures behavioral outcomes (e.g., perpetrating criminal offenses), as some argue that behaviors are manifestations of traits and not traits themselves. We respectfully reject this argument as people form and revise their idiographic array of personality traits based, in large part, on their observations of their own behaviors (Robins & John, 1997). The value of including behaviors in trait measures is reflected in the use of such behavior-based items in the widely-accepted NEO and BFI measures that we employed. As such, to accurately capture human personality, it is wise to ask people about their own behaviors, which are windows into the psychological traits that lie obscured in the mind.

There are many different approaches to the individual traits that comprise the broader construct of ‘trait aggression’ and we only examined one such approach: the Buss and Perry (1992) four factor model. Other models of trait aggression exist, such as the ‘forms and functions of aggression’ approach, which sub-divides aggression into overt and relational forms and by whether they serve reactive or proactive functions (Marsee et al., 2011). Future research is needed to examine whether our findings would replicate using measures based off these other models and whether different sub-types of trait aggression would exhibit a similar FFM profile.

10. Conclusions

After many years of existing without a clear theoretical framework, we have provided initial evidence that trait aggression has a home in the Five Factor Model of personality’s antagonism factor. By situating trait aggression within this broader conceptual scaffolding, we reject attempts to eliminate this construct from the study of human personality. Instead, investigations into trait aggression can benefit from a better articulation of this construct’s nomological network and position in the hierarchy of personality. Future research might work to further articulate trait aggression’s nomological network, distinguishing it from other facets of antagonism and identifying predictors from other domains of the Five Factor Model. Such advances in theory will hopefully bring clarity to a convoluted literature, which can be translated into improved prediction and intervention efforts for those who are most at risk for perpetrating violent acts.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Trait aggression lacks a foundation in a higher-order personality framework.

Agreeableness was the dominant trait dimension to correlate with trait aggression.

Trait aggression exhibited strongest latent correlations with low agreeableness.

Factor analyses failed to distinguish agreeableness and trait aggression items.

Trait aggression is likely a lower-level facet of antagonism (low agreeableness).

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the NIAAA under award K01AA026647 (PI: Chester).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

References

- Alfons A (2019). robustHD: Robust Methods for High-Dimensional Data (version 0.6.1) [Software] Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=robustHD.

- Allen JJ, & Anderson C (2017). Aggression and violence: Definitions and distinctions In Sturmey P (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of violence and aggression. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ando A, Soga S, Yamasaki K, Shimai S, Shimada H, Utsuki N, … & Sakai A (1999). Development of the Japanese version of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BAQ). Shinrigaku Kenkyu: The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 70(5), 384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G (2007). The Buss-Perry aggression questionnaire: Some unfinished business. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(2), 434–452. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L (1989). Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt BA, Talley A, Benjamin AJ, & Valentine J (2006). Personality and aggressive behavior under provoking and neutral conditions: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 751–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, & Smith BD (2001). Refining the architecture of aggression: A measurement model for the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(2), 138–167. [Google Scholar]

- Budescu DV (1993). Dominance analysis: A new approach to the problem of relative importance of predictors in multiple regression. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 542–551. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, & Baumeister RF (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, & Perry M (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester DS (2017). The role of positive affect in aggression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(4), 366–370. [Google Scholar]

- Chester DS, & DeWall CN (2013). Trait aggression In Eastin MS (Ed.), Encyclopedia of media violence (pp. 352–356). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chester DS, DeWall CN, & Enjaian B (2019). Sadism and aggressive behavior: Inflicting pain to feel pleasure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(8), 1252–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester DS, Lynam DR, Milich R, & DeWall CN (2017). Social rejection magnifies impulsive behavior among individuals with greater negative urgency: An experimental test of urgency theory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(7), 962–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester DS, Lynam DR, Milich R, & DeWall CN (2018). Neural mechanisms of the rejection-aggression link. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 13(5), 501–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & McCrae RR (1992). NEO personality inventory-revised (NEO PI-R). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L, & Meehl P (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), 281–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe ML, Lynam DR, & Miller JD (2018). Uncovering the structure of agreeableness from self-report measures. Journal of Personality, 86(5), 771–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, DeWall CN, & Finkel EJ (2012). Self-control and aggression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(1), 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Chester DS, & White DS (2015). Can acetaminophen reduce the pain of decision-making? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 56, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond PM, Wang EW, & Buffington-Vollum J (2005). Factor structure of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) with mentally ill male prisoners. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 32(5), 546–564. [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41(1), 417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Price JM, Bachorowski JA, & Newman JP (1990). Hostile attributional biases in severely aggressive adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99(4), 385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donate APG, Marques LM, Lapenta OM, Asthana MK, Amodio D, & Boggio PS (2017). Ostracism via virtual chat room: Effects on basic needs, anger and pain. PLoS ONE, 12, e0184215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne A, Gilbert F, & Daffern M (2018). Elucidating the relationship between personality disorder traits and aggression using the new DSM-5 dimensional-categorical model for personality disorder. Psychology of Violence, 8(5), 615–629. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, & White SF (2008). Research review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 359–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher JM, & Ashford JB (2016). Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire: Testing alternative measurement models with assaultive misdemeanor offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(11), 1639–1652. [Google Scholar]

- García-León A, Reyes GA, Vila J, Pérez N, Robles H, & Ramos MM (2002). The Aggression Questionnaire: A validation study in student samples. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 5(1), 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerevich J, Bácskai E, & Czobor P (2007). The generalizability of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 16(3), 124–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models In Mervielde I, Deary I, De Fruyt F, & Ostendorf F (Eds.), Personality Psychology in Europe, Vol. 7 (pp. 7–28). Tilburg University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR, Johnson JA, Eber HW, Hogan R, Ashton MC, Cloninger CR, & Gough HC (2006). The International Personality Item Pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR, & Hirschi T (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B, Moors A, Sander D, & Deonna J (2017). Emotion meets action: Towards an integration of research and theory. Emotion Review, 9(4), 295–298. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Eron LD, Lefkowitz MM, & Walder LO (1984). Stability of aggression over time and generations. Developmental Psychology, 20(6), 1120–1134. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Donahue EM, & Kentle RL (1991). The Big Five Inventory—Versions 4a and 54. University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Naumann LP, & Soto CJ (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues In John OP, Robins RW, & Pervin LA (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, & Srivastava S (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives In Pervin LA & John OP (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DN, & Neria AL (2015). The dark triad and dispositional aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 360–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kraha A, Turner H, Nimon K, Zientek LR, & Henson RK (2012). Tools to support interpreting multiple regression in the face of multicollinearity. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IA, & Preacher KJ (2013). Calculation for the test of the difference between two dependent correlations with one variable in common [Software]. Available from http://quantpsy.org.

- Lynam DR, & Miller JD (2019). The basic trait of antagonism: An unfortunately underappreciated construct. Journal of Research in Personality, 81, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Marsee M, Barry C, Childs K, Frick P, Kimonis E, Muñoz L, … & Lau K (2011). Assessing the forms and functions of aggression using self-report: Factor structure and invariance of the Peer Conflict Scale in youths. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 792–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Gaughan ET, Maples J, & Price J (2011). A comparison of agreeableness scores from the Big Five Inventory and the NEO PI-R: Consequences for the study of narcissism and psychopathy. Assessment, 18(3), 335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimon K, Oswald F, & Roberts JK (2013). Yhat: Interpreting regression coefficients (version 2.0) [Software] Available from http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=yhat

- Nunnally JC (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd edition). Tata McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus DL, Curtis SR, & Jones DN (2018). Aggression as a trait: The dark tetrad alternative. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (version 3.2) [Software] Available from https://www.R-project.org/.

- Raine A, Dodge K, Loeber R, Gatzke-Kopp L, Lynam D, Reynolds C, … & Liu J (2006). The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: Differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggressive Behavior, 32(2), 159–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder GD, Kumar S, Hesson-McInnis MS, & Trafimow D (2002). Inferences about the morality of an aggressor: The role of perceived motive. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 789–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W (2019). psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research (version 1.9.12) [Software] Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych.

- Robins RW, & John OP (1997). The quest for self-insight: Theory and research in accuracy and bias in self-perception In Hogan R, Johnson JA, & Briggs SR (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology, (pp. 649–680). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more (version 0.6–5) [Software]. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. Available from http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/. [Google Scholar]

- Saucier G (1998). Replicable item-cluster subcomponents in the NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 70(2), 263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaba T, Rhemtulla M, Hopwood CJ, & Bleidorn W (2020). A facet atlas: Visualizing networks that describe the blends, cores, and peripheries of personality structure. PloS one, 15(7), e0236893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe JP, & Desai S (2001). The revised NEO Personality Inventory and the MMPI-2 Psychopathology Five in the prediction of aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(4), 505–518. [Google Scholar]

- Soto CJ, & John OP (2009). Ten facet scales for the Big Five Inventory: Convergence with NEO PI-R facets, self-peer agreement, and discriminant validity. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(1), 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay PF, & Ewart LA (2005). The Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire and its relations to values, the Big Five, provoking hypothetical situations, alcohol consumption patterns, and alcohol expectancies. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(2), 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra L, Bushman BJ, & Koole SL (2018). The facts on the furious: A brief review of the psychology of trait anger. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vize CE, Collison KL, Miller JD, & Lynam DR (2020). The “core” of the dark triad: A test of competing hypotheses. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 11(2), 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vize CE, Miller JD, & Lynam DR (2018). FFM facets and their relations with different forms of antisocial behavior: An expanded meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 57, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Webster GD, DeWall CN, Pond RS, Deckman T, Jonason PK, Le BM, … & Smith CV (2014). The brief aggression questionnaire: Psychometric and behavioral evidence for an efficient measure of trait aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 40, 120–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Cheung CT,K, & Choi W (2000). Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 748–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.