Abstract

Background:

ADHD causes impairment in several life contexts and may increase stress and burden of care amongst family members. There is a lack of studies regarding gender inequalities in burden sharing in families of individuals with ADHD.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to investigate gendered burden sharing in families who were in contact with an ADHD telephone helpline in Sweden. A further aim was to identify perceived difficulties that prompted contact with the helpline.

Methods:

During a period of 28 months (from January 2013 to April 2015), calls were consecutively registered by psychologists manning the helpline through an anonymous digital form. After exclusion of 60 incomplete forms out of 1,410 (4%), information on 1,350 calls was analysed.

Results:

The analysis indicated that mothers (82.7% of all callers) had a more important role as information-coordinators for children or adolescents with ADHD, as compared to fathers (13%) or other callers (4.3%). This pattern was also observed among the calls regarding young adults with ADHD. Helpline calls primarily concerned entitlement to academic support (57.9% of calls concerning children or adolescents) and healthcare services (80.6% of calls concerning young adults and adults).

Conclusion:

The study concludes that a perceived lack of accessibility to and/or coordination of the school and health care services may be a major stressor for parents of individuals with ADHD. The burden of care through coordination of services and information-seeking may be especially increased in mothers of children, adolescents, and young adults with ADHD.

Keywords: ADHD services, care pathways, coordinator, case management, parental stress

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by profound difficulties involving inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (1). ADHD is one of the most common child psychiatric disorders with an overall pooled prevalence estimate around 5% among children and 2.8% among adults (2). The clinical presentation of ADHD is often further complicated by the presence of co-existing additional neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders, including learning disorders, anxiety and mood disorders, as well as sleep disorders (3, 4). Given the complexity of the clinical presentation, ADHD in children frequently leads to functional impairments both in home and school environments, as well as in leisure activities (5-7). In addition, parents to children with ADHD report high level of parental stress (8). Thus, the individual with ADHD and his or her family often require different kinds of support and interventions in various contexts.

The help offered to families and individuals with ADHD can be economical (e.g. care allowance) or practical (e.g. special education support at school) in combination with different interventions or treatments from health care services (e.g. pharmacological treatment and parental psychoeducative programmes). Therefore, parents are met with high expectations regarding their knowledge of complex formal support systems (9), especially since in Sweden, active case management or support with care coordination is not implemented in disability services programmes geared towards families to children with ADHD. This may be one of the reasons for why parents to children with ADHD report lack of sufficient social support, and that they often experience feelings of alienation and frustration regarding their public health care contacts (10). These circumstances suggest that families of children or adolescents with disabilities, including ADHD, are often left unsatisfied with formal support systems, and that they experience an unmet need of care coordination for themselves and their children (11). Consequently, the inadequate support and lack of knowledge regarding possible care pathways could result in an increased care burden and high parental stress (8, 11).

To reduce parental stress due to lack of care coordination support, and to facilitate access to care, some health and disability services clinics in Sweden utilise telephone helpline services. Potential benefits of helplines include readily available, anonymous and geographically unrestricted access to health information and advice (12), while it may also relieve emergency health care departments from non-urgent visits (13). Although a few studies reveal further functions and implications of a telephone helpline in health care contexts (12, 14, 15), as well as the impact on care coordination through telehealth services (16, 17), less is known about the roles of telephone helplines in care coordinating interventions and treatments for patients with ADHD. Arguably, there are advantages of analysing helpline calls concerning support or advice on ADHD. For instance, the topics and contents are discussed within a context where the callers remain anonymous and are presented with a wide variety of support. This comes with a potential of an increased understanding of the lived experiences of families with ADHD and challenges that face them. In the long run, better knowledge of the lived experiences of families living with ADHD can be used to further develop and individualise interventions and support.

The lived experiences of parents may differ depending on the gender of the parent. As noted earlier, the impact of domestic and child care responsibilities may be especially increased in families with children with ADHD. While child rearing and domestic labour in most societies would traditionally be considered women’s responsibilities, this notion has been shown to be counter-acted by changes in gender role ideologies and welfare regime structures (18, 19). Policies targeting gender inequity regarding child care and domestic labour have been enacted and implemented over several decades in Sweden. These include an integrated parental benefits system that account for both parents, as well as government subsidised childcare (20). These efforts could serve as one possible explanation for the notion of Sweden as a provider of equal opportunities for women and men, and as a country of high gender equality (21). Nevertheless, research and statistics indicate that domestic labour is generally still being shared unequally between men and women in Sweden (22), where women more often perform domestic labour and care giving activities. However, not much is known about burden sharing in families to children with ADHD. Care coordination for children and relatives with ADHD would in this context be interpreted as aspects of domestic labour, as it concerns the extended care responsibilities and well-being of a relative through the support of public service providers. These findings suggest that there may be cause for investigating possible imbalances in the levels of parental care burden that is associated with coordinating and accessing care and service. This could be a valuable contribution to discovering obstacles to parental, and in extension, familial well-being and functioning within families of individuals with ADHD.

Aims

The aim of the current study was to investigate burden sharing and distribution regarding care coordination in families who were in contact with an ADHD telephone helpline provided by a publicly funded disability services clinic specialized in ADHD. A further aim was to identify perceived difficulties that prompted contact with the telephone helpline.

The following hypotheses were tested:

Care coordination through a telephone helpline service in families of children, adolescents, and young adults with ADHD are mainly performed by mothers.

The perceived difficulties within families of children, adolescents, and young adults with ADHD that prompted contact with the telephone helpline span a variety of topics, including families’ efforts of coordinating care and service for their relatives with ADHD.

Methods

This study was conducted as part of services development at the ADHD Center, Habilitation and Health (Stockholm County Council Disability Services) Stockholm, Sweden. The study was approved by Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (DNR: 2015/1599-31).

ADHD helpline as part of the services provided by the ADHD Center

The Stockholm ADHD Center provides counselling and parental psychoeducation for families with children, adolescents, or young adults with ADHD (4-25 years).

The catchment area for the centre is all of Stockholm County, with a population of 2.2 million, about 450,000 of which are children and youths aged 4 to 25 years. Registration at the ADHD Center is voluntary, and contact with both psychiatric services or children’s medical services (for pharmacological treatment) and the ADHD Center (for family-oriented interventions) is common.

Information and availability of services provided by ADHD Center is advertised through various channels for health care service information in Sweden, including the Habilitation and Health Disability Services website (23), and the website of Sweden’s national health information service (24). Furthermore, families are provided with information on the ADHD Center and similar health care and support options when their child is first diagnosed with ADHD in an effort to establish first contact with disability services specialized in ADHD.

The ADHD telephone helpline has been in operation since 2007. The main intent of the helpline was for it to serve as an extension of the formal support provided by the ADHD Center, focussing primarily on psychoeducative methods. However, the helpline has been open to the nation-wide general public from the start. The clinical psychologists manning the helpline are experienced in psychoeducation regarding ADHD and were thus able to answer questions regarding the ADHD diagnosis (e.g., characteristic symptoms, guidelines for assessment and treatment, etc.), as well as provide counselling on issues regarding parenting strategies.

Since the inquiries directed to the helpline concern a variety of topics, an effort was made to collect information using the ADHD helpline calls to describe, evaluate, and improve the provided services.

Data collection

From January 2013 to April 2015, the psychologists manning the helpline at the ADHD Center collected general data on each helpline call using an electronic form, which was to be completed consecutively after each individual call. The form was made available to all psychologists at the ADHD Center through a digital link prior to data collection. The form was constructed in collaborative effort between psychologists at the centre with psychoeducative and counselling experience who were consulted continuously through staff meetings and follow-up assessments to confirm the content validity of the electronic form.

To ensure the feasibility of the data collection within the frameworks of clinical work, an easily administered layout was chosen. The form contained no identifying personal information, since this procedure was deemed to comply with patient confidentiality. This, however, rendered the exact nature of the callers’ relation to the child/youth unclear. The staff of psychologists who manned the helpline were instead consulted in order to obtain a rough estimate of the size of the group of callers that were registered as relatives, but were not considered as parents or primary caregivers. The registered background information included the sex of the caller; the role of the caller (i.e., family member, healthcare provider, patient, student, journalist, or other) as well as the age of the person concerned (child, 0-12 years; adolescent, 13-18 years; young adult, 18-25 years; or adult, ≥ 26 years). The counselling content was divided into topical categories with multiple choice answers: general support, related to school/education, psychiatric comorbidities, healthcare providers, social services, technical devices, parent management strategies, and other treatments (such as medication). If the counselling content was school-related, a further categorisation was conducted (e.g., legal rights, teaching strategies, special needs schools, coaching for teachers). No open-ended descriptions of the contents were registered.

The form also included additional questions concerning improvements and further services development, such as length of each call, whether the call concerned a Stockholm county resident, and other relevant circumstances regarding information and communication. These data were not reported on or discussed in the current study.

Missing data and data analysis

Out of 1,410 forms, 60 (4%) lacked information about the role of the caller or the age of the individual with ADHD that the call concerned. These forms were excluded list-wise. Thus, 1,350 forms were included in the analysis. The analysis comprised descriptive statistics and frequency tables. The following was reported: caller’s relationship with the person concerned; topics discussed in helpline calls regarding children and adolescents; topics discussed regarding young adults and adults. Data on all calls registered via the digital form were extracted to Excel 2010 and analysed using SPSS v. 23.

Results

Role of the caller and age of the person that the call concerned

Most calls to the ADHD helpline concerned a child or an adolescent. In total, 1,164 calls (86.2% of the analysed 1,350 calls) regarded persons with ADHD under 18 years of age. Nearly all calls were made by a family member, with female relatives comprising the vast majority of callers (994 out of 1,164 calls, 85.4%), compared to male relatives (148 calls, 12.7%) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Age of person concerned in call and role of caller

| Caller’s relationship with the person concerned | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Call concerned | n (% of total n, i.e., 1,350) | Female relative (% of each age group) | Male relative (% of each age group) | Professional (% of each age group) | Patient himself/herself (% of each age group) |

| Child (age 0-12 years) | 698 (51.7%) | 600 (86%) | 87 (12.5%) | 11 (1.6%) | na |

| Adolescent (age 13-17 years) | 466 (34.5%) | 394 (84.5%) | 61 (13.1%) | 11 (2.4%) | na |

| Young adult (age 18-25 years) | 153 (11.3%) | 106 (69.3%) | 21 (13.7%) | 6 (3.9%) | 20 (13.1%) |

| Adult (age ≥ 26 years) | 33 (2.4%) | 17 (51.5%) | 6 (18.2%) | 3 (9.1%) | 7 (21.2%) |

Note. n = 1,350

In total, 186 calls (13.8% of all calls) concerned a young adult (18-25 years of age) or an adult over 25 years of age. Again, most callers were female relatives (123 calls or 66.1%), compared to 27 calls from male relatives (14.5%). In only 14.5% of all calls concerning young adults or adults (27 calls), the caller was the patient him/herself (Table 1).

Staff psychologists and a former manager of the ADHD Center provided (independently of each other) an estimate of the size of the groups of female and male relatives who were, respectively, considered as non-parents nor primary caregivers. For calls concerning children aged 0 to 12, the number of callers registered as relatives, but not considered to be parents or primary caregivers were estimated to be 1 to 4%. For adolescents aged 13 to 18, the number was estimated to be 1 to 3%. For young adults and adults aged 18 and above, the number was estimated to be 2 to 10%. These consistent estimations from staff psychologists and a manager suggest that the vast majority of the calls were made by mothers and fathers, for all age groups, rather than other relatives. For young adults and adults, the second largest group of callers that were registered as relatives were most often considered to be siblings or partners.

Counselling content

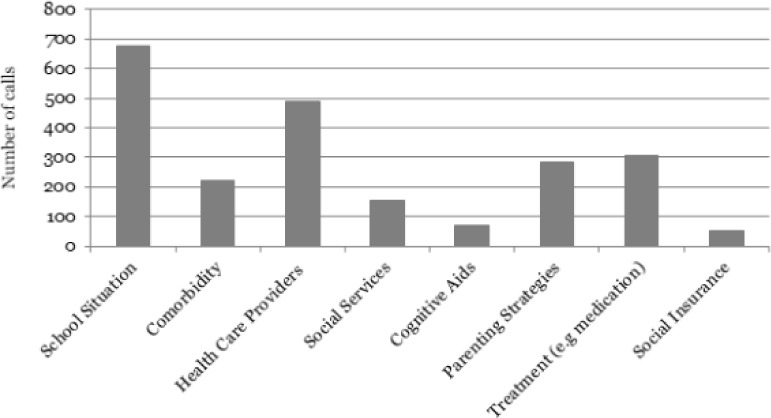

Most calls regarding persons under 18 years of age covered several topics (Figure 1), with questions regarding the child’s or adolescent’s situation at school being most recurrent (discussed in 674 calls or 57.9% of all analysed calls to the ADHD helpline regarding persons under 18 years of age). This was followed by questions regarding contacts with other healthcare providers (501 calls, 43%). When a helpline call concerned the situation at school, the most common concern was legal rights to academic support (480 calls, 71.2% of all calls regarding school situation). Parenting strategies were discussed in 282 calls (20.9% of all calls) and treatment of ADHD in 306 calls (22.7%).

FIGURE 1.

Topics discussed in helpline calls regarding children and adolescents (n = 1,164). Many calls concerned several topics (coded for each theme)

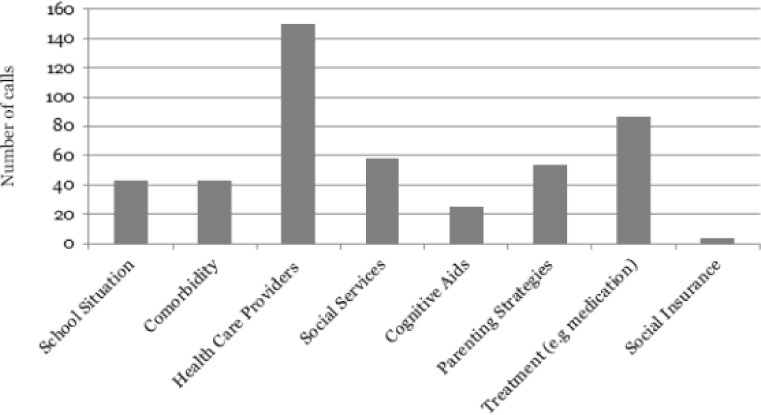

The helpline calls regarding young adults and adults had a somewhat different distribution of topics. Here, the most common topics discussed were contacts with other health care and service providers and treatments (150 out of 186 calls, i.e., 80.6%) (Figure 2). The follow-up discussions with the psychologists manning the helpline indicated that the nature of the calls mainly concerned difficulties receiving psychiatric and psychological treatment for ADHD or co-existing psychiatric conditions, such as depression and anxiety. A theme that was commonly noted in conversations with parents of young adults and adults was the parents’ frustrations over not being involved in treatment planning, as well as difficulties among parents to motivate their grown children to seek treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Topics discussed in helpline calls regarding young adults and adults (n = 186). Many calls concerned several topics (coded for each theme)

Discussion

The analysis of 1,350 calls to the ADHD telephone helpline suggests that callers did not primarily seek advice on parenting strategies or treatment (the initial focus of the ADHD helpline), but more often wanted information about their child’s rights to special accommodation and academic support. This finding suggests that callers utilised the support offered by the helpline for care coordination purposes, rather than receiving counselling or psychoeducative support.

The analysis further indicates that female family members performed care coordinating efforts and inquiry on behalf of a child with ADHD to a much higher degree than male family members. On the basis of the follow-up assessments with psychologists manning the helpline, the female family members of individuals with ADHD calling the helpline were predominantly mothers. Moreover, this further indicate that the care coordinating responsibilities of parents of children with ADHD often extended beyond childhood and adolescence into adulthood, as mothers tended to manage care and support contacts for their grown children.

Increased understanding of aspects of gender is essential in the context of care burden for individuals with ADHD. Living with ADHD has proven to be not only stressful for the affected child, adolescent (25), or adult (26, 27), but may also cause stress and worry for family members. Although both mothers and fathers of adolescents with ADHD have reported more stress than parents of typically developing adolescents with regard to their children’s challenging behaviours, mothers also report feelings of social alienation, guilt, incompetence and elevated conflicts with their partner (28). Furthermore, studies that have included both mothers and fathers indicate gender differences in perception of the child’s behaviour and perceived parental stress (28, 29). The finding that female relatives are more active in seeking and coordinating help is corroborated by an abundance of research showing that mothers generally spend more time than fathers on domestic chores and child rearing, which also includes the mental and emotional labour of domestic responsibilities (30-32), and that mothers worry about family matters to a greater extent than fathers (31). Despite these findings, there is still, however, little knowledge on how to address these differences in the perception of parental stress in a clinical setting, especially when it comes to fathers’ participation in the care of their children with ADHD. Thus far, less is also known about the ways in which fathers to the children with ADHD cope with parental stress. In order to further investigate the experiences of stress and coping strategies among fathers, and in turn, address these issues, more research is warranted.

As Sweden is often presented as a society for equal opportunities between men and women in both private and public spheres, the seemingly large care burden laid on mothers proves especially concerning. As Swedish families largely consist of dual-earner households (33), it begs the question of how an increased care burden on mothers with ADHD may effect female workforce participation long term. One Swedish study has indicated that mothers of children with intellectual disabilities (ID) are shown not only to be less involved in paid work than mothers of typically developing children, but also less than of fathers of children with ID (34). However, this pattern can be noted in society at large, as women tend to work part-time more than men in order to cope with high demands in both work and family settings (35), and that spillover of work into family life may contribute to mothers’ feelings of stress (31). The current study thus highlights the importance of identifying difficulties and struggles associated with coordinating care for individuals with ADHD, in order to relieve mothers of a high care burden. While this may be especially valuable in further addressing the needs of mothers in coordinating care for their children with ADHD, the current study’s findings may also be interpreted as a display on public health care services’ inability to reach fathers of children with ADHD, and thus failure to accommodate the needs of families as a whole.

Although the content of the calls to the ADHD helpline could not be recorded in detail due to the sensitive nature of the information, our data suggest that many parents were uncertain as to what kind of help they and their child could expect to receive from the health care or educational system, and that they often were dissatisfied with the help they received. These assumptions were confirmed in follow-up interviews with the psychologists manning the helpline, and the results are in agreement with those of previous qualitative studies indicating that the parents of children with ADHD experience discontent with the lack of information and coordination of healthcare services (36-38).

In recent years, it has been suggested by several studies (9, 10) that coordinating care and services for individuals with disabilities is a highly challenging task. This has been shown to be true even in cases where the individual is formally eligible for care through diagnosis (9). This study highlights these challenges by revealing the unmet needs of information and coordination of care among relatives of individuals with ADHD. The results indicate that the task of care coordination is mainly performed by a patient’s relative, in most cases by the mother of the patient, also regarding emerging adults with ADHD. This finding is well in line with previous research (39) showing that individuals diagnosed with ADHD as children were dependent on their parents as young adults to a much higher degree than individuals who were never diagnosed with ADHD.

Limitations and strengths

The registration of calls to the ADHD helpline was not connected to patient case files, therefore we cannot be certain that the investigation covers all calls made during the study period. Since the routine for the registration was well-established, however, we estimated that only a small amount of calls escaped registration. Also, some individuals may have called the ADHD helpline several times during this period and thus have multiple registered calls. The follow-up interviews indicated that on occasion, some individuals contacted the helpline several times. However, it was rare for any individual to call the helpline more than two or three times in a year, and thus, there is no reason to suspect systematically missing data or duplicate data would have a noticeable effect on the results of this study.

Another limitation of the study is the lack of knowledge on the specifics of burden sharing and distribution between female and male relatives within families. The concept of care coordination as an act of domestic responsibilities, in this study’s findings, merely reflects patterns in which families tend to distribute these responsibilities. Thus, we cannot be certain if the skew in female and male care coordination practices will negatively impact parental well-being and be associated with higher levels of parental stress.

One strength of the current study is its large number of data (n = 1,350). Although the problems described by these parents are in line with findings from previous research, we cannot be sure that the parents who chose to contact the ADHD helpline are representing the group as a whole. Despite a nation-wide access of the helpline service, the study was conducted in a limited geographical area and thus hinders generalisability of our results. However, the problems described by parents in this study are seemingly in line with findings from previous research.

All limitations considered, the results of this study still indicate that unmet needs for care coordination are the main reasons for relatives of children, adolescents, and young adults with ADHD to seek information and counselling. The coordination of services, including information-seeking, is primarily done by female relatives (mothers) of individuals with ADHD and thus may constitute an inequality within families regarding the burden of care.

Clinical significance

To increase the patient’s active participation in his/her healthcare, as well as enhancing the patient’s integrity and autonomy in the transition from adolescence to adulthood, active case management may be needed. The potential benefits of case management are twofold: parents of young adults and adolescents with ADHD may experience a lessened burden when it comes to coordinating care and services; similarly, parents of younger children with ADHD may become more efficient, knowledgeable, and well accommodated in coordinating care and services for their children. However, interventions increasing parental well-being and reducing parenting stress may in some cases be a prerequisite for parents’ ability to engage as change agents in their child’s care processes. Comprehensive and integrated transition services providing knowledge, and skills to gradually increase independence, may be especially important for the emerging adults with ADHD.

By identifying a skew in the burden of care between men and women as care coordinators for relatives with ADHD, this study further emphasises the intricacies and persistence of gender role structures in modern parenthood. In order for clinicians to effectively accommodate the needs of individuals with disabilities and their families, there needs to be an increased awareness of these matters in several clinical contexts, as well as individualised interventions geared towards differing needs. Involvement of both mothers and fathers may benefit the entire family system by increased sharing of both burden and enjoyment in families living with ADHD.

As of the time of writing, services offered through the telephone helpline at ADHD Center following the end of the data collection have been restricted to psychoeducation or counselling, and callers inquiring information regarding academic support or health care services are, since 2015, directed to another telephone helpline service manned by social workers. The need for two separate telephone helplines that more clearly specialized in psychoeducation and counselling versus information and coordination of health care and education was noted during and after data collection was finished, in particular due to the perceived difficulties that were put forward by a majority of callers to the telephone helpline. Therefore, follow-up studies on ADHD patients and their relatives’ experiences of care coordination are warranted.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous participants as well as psychologist staff at the ADHD Center; Lena Westholm, Linda Maurin, Sahar Gaveli, Corinna Brazel, and Elin Lindqvist, and former Head of the ADHD Center, Agneta Hellström, for their contributions to this project. The authors would also like to thank Dany Kessel from the Stockholm University Department of Economics for his help with Excel programming.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding this study.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:434-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hvolby A. Associations of sleep disturbance with ADHD: implications for treatment. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2015;7:1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larson K, Russ SA, Kahn RS, Halfon N. Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics 2011;127:462-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barkley RA. Major life activity and health outcomes associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63 Suppl 12:10-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer TJ, Mick E, Monuteaux MC, Aleardi M. Functional impairments in adults with self-reports of diagnosed ADHD: a controlled study of 1001 adults in the community. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:524-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wender PH, Wolf LE, Wasserstein J. Adults with ADHD: an overview. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001;931:1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theule J, Wiener J, Tannock R, Jenkins JM. Parenting stress in families of children With ADHD. J Emot Behav Disord 2013;21:3-17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowak HI, Broberg M, Starke M. Parents’ experience of support in Sweden: its availability, accessibility, and quality. J Intellect Disabil 2013;17:134-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SBU ADHD – diagnostics and treatment, organisation of the health care and patient involvement. Stockholm: Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment Stockholm (SBU); 2013. SBU report; 217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown NM, Green JC, Desai MM, Weitzman CC, Rosenthal MS. Need and unmet need for care coordination among children with mental health conditions. Pediatrics 2014;133:530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopriore S, LeCouteur A, Ekberg S, Ekberg K. Delivering healthcare at a distance: exploring the organisation of calls to a health helpline. Int J Med Inform 2017;104:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen K, Crane J. Optimising patient flow through the emergency department. In: Kayden S, Anderson PD, Freitas R, Platz E (Eds). Emergency department leadership and management: best principles and practice, 1 ed Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014:247-56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greatbatch D, Hanlon G, Goode J, O’Cathain A, Strangleman T, Luff D. Telephone triage, expert systems and clinical expertise. Sociol Health Illn 2005;27:802-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lechner L, De Vries H. The Dutch cancer information helpline: experience and impact. Patient Educ Couns 1996;28:149-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Looman WS, Antolick M, Cady RG, Lunos SA, Garwick AE, Finkelstein SM. Effects of a telehealth care coordination intervention on perceptions of health care by caregivers of children with medical complexity: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Health Care 2015;29:352-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKissick HD, Cady RG, Looman WS, Finkelstein SM. The impact of telehealth and care coordination on the number and type of clinical visits for children with medical complexity. J Pediatr Health Care 2017;31:452-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris RJ, Firestone JM. Changes in predictors of gender role ideologies among women: a multivariate analysis. Sex Roles 1998;38:239-52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geist C. The welfare state and the home: regime differences in the domestic division of labour. Eur Sociol Rev 2005;21:23-41 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Försäkringskassan Parental benefit. Swedish Social Insurance Agency; 2019. Available from: https://www.forsakringskassan.se/privatpers/foralder/nar_barnet_ar_fott/foraldrapenning/!ut/p/z0/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8ziTTxcnA3dnQ28_U2DXQwczTwDDcOCXY1CDc31g1Pz9AuyHRUBTbm8uw!!/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Global Gender Gap Report 2017 Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2017. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2017 [Google Scholar]

- 22.SCB Tidsanvändningsundersökningen 2010. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden; 2010. Available from: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/levnadsforhallanden/levnadsforhallanden/tidsanvandningsundersokningen/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habilitation and Health Stockholm: Stockholm County Council; 2019. Available from: http://habilitering.se/home [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vårdguiden. Stockholm: Stockholm County Council; 2019. Available from: https://www.1177.se/Stockholm/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahlstrom BH, Wentz E. Difficulties in everyday life: young persons with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorders perspectives: a chat-log analysis. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2014;9:23376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirvikoski T, Lindholm T, Nordenstrom A, Nordstrom AL, Lajic S. High self-perceived stress and many stressors, but normal diurnal cortisol rhythm, in adults with ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). Horm Behav 2009;55:418-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raz S, Leykin D. Psychological and cortisol reactivity to experimentally induced stress in adults with ADHD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;60:7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiener J, Biondic D, Grimbos T, Herbert M. Parenting stress of parents of adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2016;44:561-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig F, Operto FF, De Giacomo A, Margari L, Frolli A, Conson M, et al. Parenting stress among parents of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Psychiatry Res 2016;242:121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:344-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Offer S. The costs of thinking about work and family: mental labour, work–family spillover, and gender inequality among parents in dual-earner families. Sociol Forum 2014;29:916-36. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yavorsky JE, Dush CMK, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ. The production of inequality: the gender division of labor across the transition to parenthood. J Marriage Fam 2015;77:662-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eklund L, Lundqvist Å. Children’s rights and gender equality in Swedish parenting support: policy and practice. J Fam Stud 2018:1-16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsson MB, Hwang CP. Well-Being, involvement in paid work and division of child care in parents of children with intellectual disabilities in Sweden. J Intellect Disabil Res 2006;50:963-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bianchi SM. Maternal employment and time with children: dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography 2000;37:401-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brinkman WB, Sherman SN, Zmitrovich AR, Visscher MO, Crosby LE, Phelan KJ, et al. Parental angst making and revisiting decisions about treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 2009;124:580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dennis T, Davis M, Johnson U, Brooks H, Humbi A. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: parents’ and professionals’ perceptions. Community Pract 2008;81:24-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fiks AG, Hughes CC, Gafen A, Guevara JP, Barg FK. Contrasting parents’ and pediatricians’ perspectives on shared decision-making in ADHD. Pediatrics 2011;127:e188-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biederman J, Petty CR, Woodworth KY, Lomedico A, Hyder LL, Faraone SV. Adult outcome of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controlled 16-year follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:941-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]