Abstract

This chapter synthesizes what is known about the relationship between social disadvantage and measures of low health literacy (LHL), and reviews the research examining whether LHL is an explanatory factor connecting social disadvantage, health outcomes, and health disparities. Written from a U.S. perspective, the chapter then offers a novel conceptual framework that presents how the social determinants of health might interact with LHL to result in health disparities. The framework articulates relationships that reflect public health pathways and healthcare pathways, which include their related health literacies. In addition, the chapter highlights as an exemplar one important potential causal mechanism in the healthcare pathway by exploring the communication model in outpatient care, as communication has been very well-studied with respect to both health disparities and HL. The chapter then, provides two examples of HL interventions aligned with the conceptual framework, one of which addresses the health care literacy pathway, and the other addresses the public health literacy pathway. The chapter continues with a number of cautionary statements based on the inherent limitations of current HL research, including problems and concerns specific to the attribution of HL as an explanatory factor for extant socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health disparities. The chapter closes with recommendations regarding future research directions.

Keywords: health disparities, health literacy, social ecological model, public health, race and ethnicity, communication, measurement, discrimination, health policy

1. Introduction

This chapter attempts to synthesize what is known about the relationship between social disadvantage and measures of low health literacy (LHL), and to review the research examining whether LHL is an explanatory factor connecting social disadvantage, health outcomes, and health disparities. Written from a U.S. perspective, the chapter also offers a novel conceptual framework that presents how the social determinants of health might interact with LHL to result in health disparities. The latter articulates relationships that reflect public health pathways (e.g. the socio-ecological model, differential exposures and life course perspectives) and healthcare pathways (including health literate healthcare organizations), which include their related health literacies. In addition, the chapter focuses on one important potential causal mechanism in the healthcare pathway by exploring the communication model in outpatient care; communication has been well-studied with respect to both health disparities and HL. The chapter then provides two examples of HL interventions aligned with the conceptual framework that address the health care literacy and public health literacy pathways. The chapter continues with a number of cautionary statements based on the inherent limitations of current HL research, including problems and concerns specific to the attribution of HL as an explanatory factor for extant socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health disparities. The chapter closes with recommendations regarding future directions.

2. Operational Definitions of Terms

Social Determinants of Health:

The complex, integrated, and overlapping social structures and economic systems that are responsible for most health inequities. These social structures and economic systems include the social environment, physical environment, health services, as well as structural and societal factors. Social determinants of health are shaped by the current and historic distribution of money, power, and resources throughout local communities, nations, and the world [1]. This chapter primarily discusses the social determinants of low income/poverty, low educational attainment, racial/ethnic minority status, and linguistic isolation.

Health Equity:

A set of conditions in which all people have the opportunity to attain their full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of their social position or other socially determined circumstance [2].

Health Disparity:

A type of difference in health that is closely linked with social or economic disadvantage. Health disparities negatively affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater social or economic obstacles to health. These obstacles stem from characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion such as race or ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, gender, mental health, sexual orientation, indigenous status or geographic location. Other characteristics include cognitive, sensory, or physical disability [3].

Vulnerable Populations:

Subgroups of the larger population that, because of social, economic, political, structural, geographic and historical forces, are exposed to a greater risk of risks, and are thereby at a disadvantage with respect to their health and health care [4]. Vulnerable populations are exposed to contextual conditions that distinguish them from the rest of the population.

Socio-Ecological Model of Health:

Identifies factors affecting behavior and also provides guidance for developing successful programs through social environments. Social ecological models emphasize multiple levels of influence (such as individual, interpersonal, organizational, community and public policy) and the idea that behaviors both shape and are shaped by their surrounding social environment. The principles of socio-ecological models are consistent with social cognitive theory, which suggest that creating an environment conducive to change is important to facilitate the adoption of healthy behaviors.

Mediator Variable:

A major goal of health disparities research is to identify and intervene upon modifiable risk factors or exposures that help explain the observed associations between social factors and adverse health outcomes. A mediating variable is one that partially or completely explains the relationship between an independent variable (e.g. an exposure or a risk factor) to a dependent variable (such as a health outcome). Analyses of mediation can allow researchers to move beyond merely asking “Does this risk factor/exposure lead to worse health?” to asking “How does this risk factor/exposure lead to worse health?” Statistical methods that incorporate analysis of mediators show promise with respect to identifying evidence-based targets for interventions to reduce health disparities.

3. Limited Health Literacy and Social Disadvantage

It is estimated that one-third to one half of the U.S. adult population has LHL, which is defined by the U.S. Institute of Medicine as a limited capacity to obtain, process, and understand the basic health information and services needed to make informed health decisions [5]. While LHL affects individuals across the spectrum of socio-demographics, LHL disproportionally affects vulnerable populations [6]. These include: the elderly; the disabled; people of lower socioeconomic status; ethnic minorities; those with limited English proficiency, and persons with limited education [7].

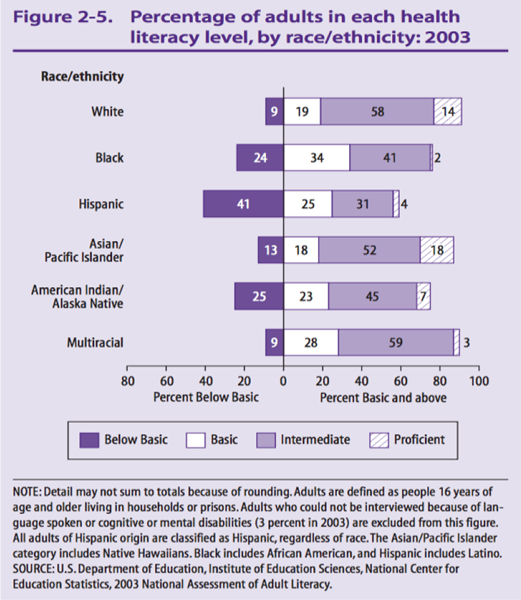

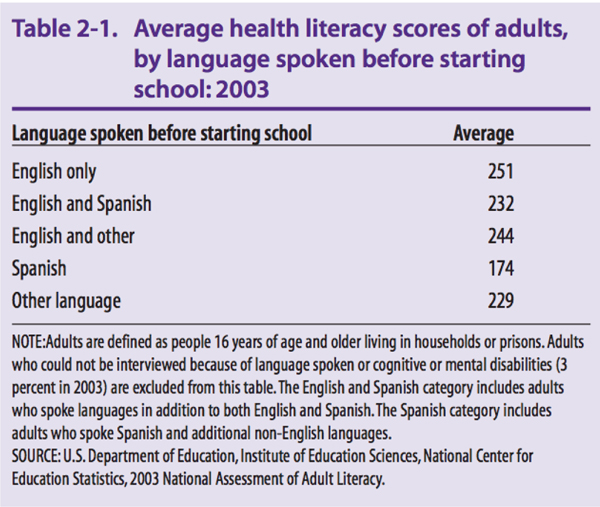

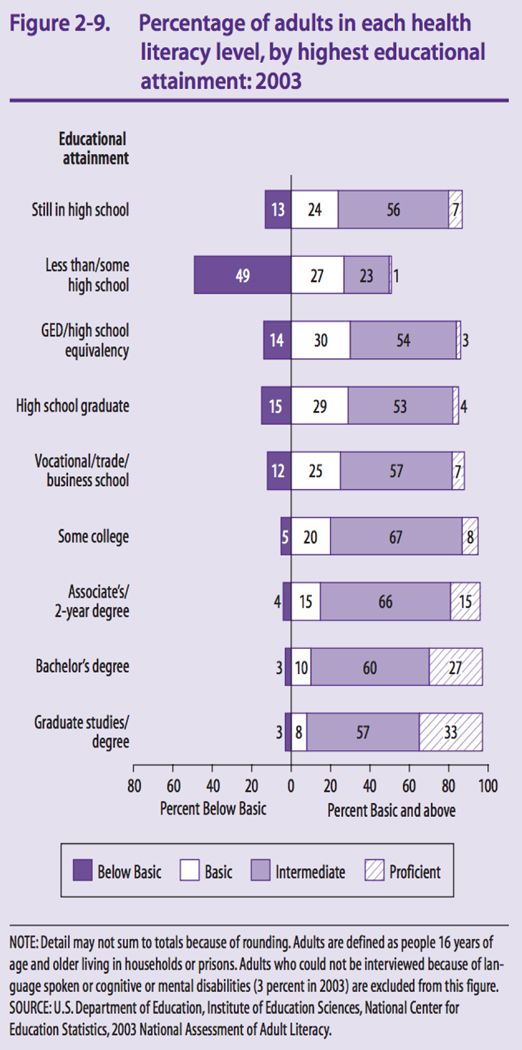

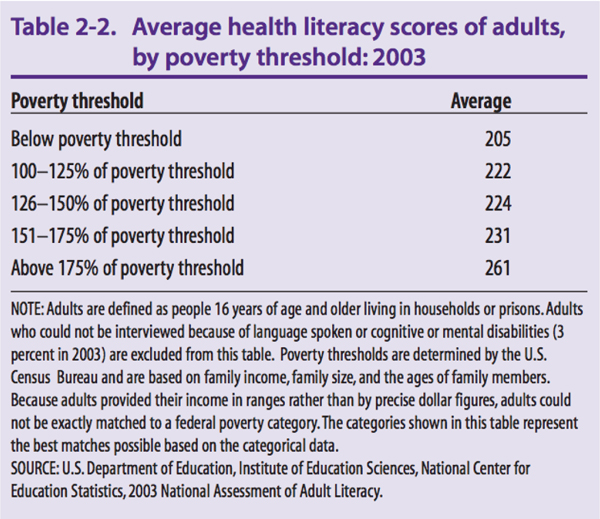

The most comprehensive assessment of variation in HL skills across different social groups occurred in 2003 as part of the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) [7]. Assessments were carried out in person; individuals had to be age 16 or over and be able to speak English or Spanish fluently. Results of the NAAL (reported in figures 1–4) suggested significant differences in the distribution of HL skills by: race and ethnicity; educational attainment; income; and language spoken before starting school. A more recent study using data from the 2013 Health Information National Trends Survey confirmed these findings [8].

Figure 1.

Percentage of adults in each health literacy level, by race/ethnicity (2003)

Figure 4.

Average health literacy scores of adults by language spoken before starting school (2003)

LHL should not be considered a ‘diagnosis,’ but rather a common pathway, marker for (or manifestation of) a number of life circumstances, including but not restricted to limited access to education, access to poor quality education, limited English proficiency, learning differences and disabilities, and cognitive impairment. Patients with LHL are more likely to have poor health, higher rates of chronic disease, and a nearly twofold higher mortality rate as compared to patients with adequate HL [9].

Compared to those with adequate HL, persons with LHL also are more likely to experience disparities in health and health care access - and have lower rates of receiving screening and preventive services. Patients with LHL exhibit patterns of utilization of care reflecting a greater degree of unmet needs, such as excess emergency room visits and hospitalizations, even when comorbid conditions and health insurance status are statistically held constant. Patients with LHL are more likely to have poorer knowledge of their disease processes, medication regimens, and exhibit worse medication adherence and inadequate skills and methods for managing their disease [9–10]. LHL also has a negative effect on doctor-patient communication. Patients with LHL more often use a passive communication style with their physician, are less likely to engage in shared decision-making, and are more likely to report that interactions with their physician are not helpful or empowering. It has been estimated that LHL leads to excess health expenditures of greater than $100 billion annually [11].

4. Evidence Connecting Health Literacy with Health Disparities

The problem of health disparities experienced within vulnerable populations is largely one of differential exposures and associated behaviors that eliminates some of the ‘shame and blame’ often associated with the higher burden of disease among socially disadvantaged people. As such, social vulnerability is not necessarily an attribute that is intrinsic to individuals or sub-populations; instead vulnerability status is determined by how society and its institutions are constructed. LHL is tightly and simultaneously linked to a number of social determinants of health. Some investigators and health policy experts have even considered LHL itself to be a social determinant of health. The high burden of LHL among vulnerable populations has led many to believe that LHL is a contributor to both health and healthcare disparities. In turn, an ensuing question is: might health literacy (HL) partially explain the health disparities associated with the social determinants of health? While the issue is of paramount importance, relatively little collaborative research has provided an empirically rigorous answer [12].

In public health practice in the U.S., vulnerable groups are often considered to be of (a) certain races and ethnic minorities, (b) low income, (c) those with a high school diploma or less, and (d) immigrants and those with limited English proficiency. Recent research, including a systematic review, focuses on (a) and (c) with respect to the question of whether HL explains some of the relationships between social circumstances and health outcomes [13]. In addition, the extant research is varied with regard to health-related outcomes and the HL assessments used. In general, multivariable modeling has been used in an attempt to determine independent effects of predictors and mediating variables on specific health outcomes. Some evidence has reported a mediating function of HL on health outcomes across racial/ethnic and educational disparities. Some evidence suggests the potential effect of HL and numeracy on racial/ethnic disparities in health behaviors and knowledge. In all research with positive associations, the effect of the mediation was partial; HL did not fully explain broader relationships.

More specific research about: health disparities related to educational attainment; health disparities related to race/ethnicity; health disparities between ethnic and linguistic sub-groups; prospective studies; and a public health perspective are outlined below.

4.1. Health Disparities Related to Educational Attainment

While a number of cross-sectional studies have explored HL as a meditating factor in the relationships between socioeconomic disparities and health outcomes, the following research specifically evaluates the relationship among HL, other variables, and educational attainment. An assessment by Bennett and colleagues (of nearly 3,000 adults over age 65 who participated in the NAAL) found HL mediated the relationship between educational attainment and self-rated health, receipt of flu vaccines, receipt of mammograms, and dental care [14–15].

A study by Howard and colleagues (of more than 3,000 seniors who participated in the Prudential Study) found HL explained the relationship between education and physical and mental health scores, but not preventive care use, such as flu vaccine, mammograms, and dental care [16]. A study by Yin and colleagues (of parents who participated in NAAL) found HL mediated the relationship between educational attainment and HL-related tasks regarding child health, dosing medications, and pediatrician appointments.

Sentell and Halpin studied 24,000 participants in the NAAL (performed in the 1990s) and found HL mediated the relationship between education and the presence of chronic illness and a health condition that limited ability to function in society [17]. Similarly, in a study of more than 14,000 persons with diabetes in a large, pre-paid integrated health plan, Sarkar and colleagues found HL mediated the relationship between educational attainment and patient’s use of an electronic patient portal, which was associated with better health outcomes [18]. Finally, Schillinger and colleagues studied a diverse sample of more than 400 public hospital patients with diabetes and found HL mediated the relationship between education and hemoglobin A1c (a measure of diabetes control) [19].

4.2. Health Disparities Related to Race/Ethnicity

As to whether HL explains racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes, a number of cross-sectional studies - some already mentioned, some additional - have looked at the explanatory power of HL with respect to black/white differences in health outcomes; few studies have assessed other racial or ethnic differences. Bennett and colleagues (2009) found HL mediated the relationship between race and self-rated health and flu vaccine receipt, but not mammography or dental care [15]. Howard and colleagues (2006) found HL mediated the relationship between race and mental health but not physical health and not the receipt of preventive care [16].

Sentell and Halpin found HL mediated the relationship between race and long-term illness and a limiting health condition, just as HL did with education [17]. In a study of 373 parents, Bailey and colleagues found HL mediated the relationship between race and misunderstandings about liquid medication dosing [20]. Osborn and colleagues found diabetes-related numeracy mediated the relationship between race and Hemoglobin A1c (a measure of blood sugar control), an effect seen primarily in diabetes patients who used insulin [21]. In patients with prostate cancer, Wolf and colleagues found HL mediated the relationship between race and the level of prostate-specific-antigen (PSA) at the time of presentation with prostate cancer [22]. Osborn and colleagues found HL mediated the relationship between HL and diabetes medication adherence [23]. Another study suggested that, while HL reduced the effect of race/ethnicity in African Americans and Hispanics on asthma quality of life and asthma control (and for African Americans only on emergency department visits), differences between African Americans and whites for asthma-related hospitalizations remained [24]. Finally, a study of more than 225 mostly black and white patients demonstrated HL mediated the relationship between race and a measure of patient activation [25].

4.3. Health Disparities between Ethnic and Linguistic Sub-Groups

Relatively few studies have explored the effects of HL in health disparities experienced by Hispanic or Asian sub-groups, and still fewer have examined HL’s role in explaining health disparities associated with limited English proficiency (LEP). A study comparing Spanish to English speakers in an emergency department suggested only the former were less likely to keep up follow-up appointments if they had LHL [26]. A study of Asian Americans found LHL was not significantly associated with meeting colorectal cancer screening guidelines, but LEP was [27]. However, the combination of LEP and LHL had synergistic effects among Asians. A large study that featured diverse participants found LHL was only significantly related to health status in whites and ‘other races,’ but not within any Asian group. However, the study found the highest odds of poor health status occurred among Chinese, Vietnamese, Hispanics and ‘other races’ with LHL and LEP [28]. Similar synergistic effects were observed on patient-reported interpersonal communication outcomes in a large sample of English and Spanish speaking primary care patients [29]. LHL and LEP each was associated with worse communication within the receptive, expressive, and interactive domains of interpersonal communication, while the combination was associated with the worst communication.

4.4. Prospective Studies

Only five prospective studies have examined the question of HL as a mediator of health disparities. In a longitudinal cohort study with 342 black, Hispanic and white adults with persistent asthma, HL mediated the relationship between race/ethnicity and asthma-related hospitalizations and ED visits [30]. In a before and after trial, Volandes et al. found HL mediated the relationship between race and changes in advanced care preferences [31]. After viewing a video, patient preferences, particularly among those with low HL, changed to preferring less aggressive care. Otherwise, an experiment of the differential effects of race/ethnicity (black vs. white) and HL that studied response to a telephone-based osteoarthritis self-management support intervention) found a significant interaction between HL and race/ethnicity on change in pain; non-whites with low HL had the highest improvement in pain in the intervention compared to the usual care group [32]. Finally, a natural experiment (involving more than 8,000 ethnically diverse patients with diabetes to enhance medication adherence, implementation of an intervention to promote mail-order pharmacy use that was not tailored for patients with LHL) reported a differential uptake of the intervention that further disadvantaged LHL patients, especially among Latino, and lower income subgroups [33]. A trial of literacy-appropriate, easy-to-understand video narratives and testimonials (presented in English and Spanish to encourage advance care planning demonstrated improvements across HL levels) yielded additional benefits for Spanish speakers, although the interaction between study arms and language was not statistically significant [34].

4.5. A Public Health Perspective

In reviewing this literature, it is important to note that many studies applied clinical epidemiologic approaches to address the larger question whether LHL can explain health disparities by either exploring the interactions among HL and a particular social determinant (e.g. race, education) on health outcomes, or performing formal meditational analyses. In so doing, investigators attempted to answer whether HL had differential effects on health outcomes based on an individual’s race or educational attainment.

Yet from a public health perspective (given the disproportionately high prevalence of LHL among vulnerable populations), these types of analytic approaches may be overly reductionist. Insofar as LHL is more prevalent in socially disadvantaged populations, and insofar as LHL appears to be an explanatory factor in the development of illness or its complications across populations, interventions to effectively address LHL are likely to result in a reduction in health disparities. Yet, the effect may be because LHL is equally distributed across the U.S. population more than the unique explanatory power of LHL.

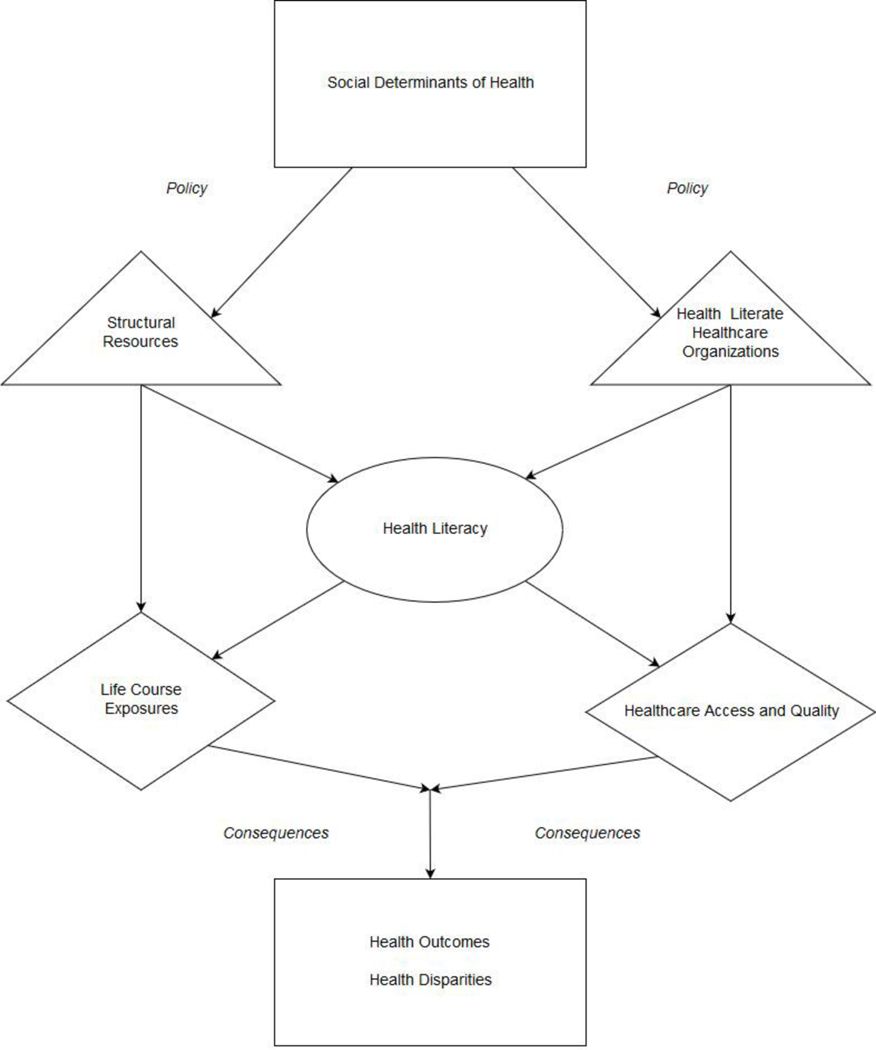

In turn, figure 5 in section five describes a novel conceptual framework that integrates a social-ecological model with the more traditional causal frameworks associated with HL. The proposed conceptual model synthesizes research from multiple disciplines (such as clinical epidemiology; health services research; anthropology; health communication science; and public health) to better explain the potential pathways by which the social determinants of health, HL, and health disparities interact. The framework, and its explication, elucidate pathways and its associated factors additionally provide potential targets for intervention in the effort to reduce health disparities.

Figure 5:

Conceptual Framework for the Pathways that Connect Social Determinants of Health, Health Literacy and Health Disparities. Pathways on the right represent healthcare pathways; those on the left represent public health pathways

5. Conceptual Framework for the Relationships Between Social Determinants of Health, Health Literacy and Health Disparities

Figure 5 suggests there are two predominant pathways through which social determinants of health and social disadvantage can interact with LHL to result in health disparities. The first is the public health pathway (on the left of Figure 5) that suggests the structural factors that reflect the (mal) distribution of health-promoting resources and unhealthy life course exposures across the general population in the U.S. The second is the healthcare pathway (on the right of Figure 5) that suggests the organizational factors that reflect the responsiveness of health systems to the needs of clinical populations in the U.S. - with respect to access to and quality of care. Differences in resources and exposures in public health and community settings, as well as differences in access and quality in clinical settings, both foster consequences that contribute to worse health outcomes and health disparities. Several of the constructs and variables within Figure 5 are introduced below.

5.1. Social Determinants of Health

This box (and construct) is the starting point for all pathways and reflects the unequal distribution of health-promoting resources and unhealthy life course exposures resulting from differences in social status, often instigated, reinforced, or perpetuated by social policy and practice. This construct focuses on sub-populations of low income/poverty status; low educational attainment; racial and ethnic minority populations subject to marginalization or oppression; and those with LEP/linguistic isolation.

5.2. Structural Resources and Life Course Exposures

The triangle and diamond represent the factors within the public health pathway protective to health with those that jeopardize health, which often shape health behaviors. These factors - so-called ‘structural determinants’ - flow from institutional, local, state and federal policies, and generate facts on the ground that can profoundly affect individuals, families, neighborhoods, etc. The balance between health-promoting resources and risk exposures over the life course are a major determinant of the health of individuals and communities. Some of these structural factors include: air quality/pollution; safe and green spaces for physical activity and recreation; features of the built environment and associated zoning regulations; transportation infrastructure; housing/segregation; the retail food environment/food deserts; commercial marketing environments (such as advertisements on billboards for unhealthy products); employment opportunities and occupational hazards; community stress and trauma; presence or absence of public health-promoting regulations; social support; social cohesion; and social investment.

5.3. Related Health Literacy Domains

Within the public health pathway, HL is depicted as both a product of the social determinants of health as well as a potential asset that can positively influence the balance between health-promoting resources and unhealthy risk exposures, and/or mitigate the ill effects of unhealthy exposures. Health exposures include: environmental HL; occupational HL; nutritional HL; mental HL; and the larger construct of ‘public health’ literacy. Public HL can be an attribute of an individual, a community, or an entire population. Public HL refers to the degree to which individuals and groups can obtain, process, understand, evaluate, and act upon information needed to make public health decisions that benefit the community [35]. Public HL aims to engage more stakeholders in public health efforts and address determinants of health. It requires an understanding of conceptual foundations related to the socio-ecological model of health, critical skills, and a civic orientation. While advocacy and policy change are its currency, improving the health of the public is its ultimate objective.

5.4. The Consequences

The depiction of the (mal) distribution of resources and exposures between populations, compounded by a disproportionately high rate of LHL of the types described above among vulnerable populations, has real consequences for health behavior and health status. These include higher rates of chronic diseases, such as: obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and stroke, and asthma; cancer; mental health problems related to trauma, toxic stress and PTSD, substance use disorders, and depression; and disability.

5.5. Health Literate Healthcare Organizations

The depicted triangle represents the next step in the healthcare pathway connecting social determinants of health, HL, and health disparities. Schillinger, Keller and Brach defined health literate health care organizations (HLHCOs) as those that ensure HL is deeply and explicitly integrated into all of their activities - and HL informs both strategic and operational planning [36]. Appropriate measures to evaluate specific HL initiatives are developed and used. More importantly, the measurement of overall organizational performance assesses success with vulnerable populations. However, because of inadequacies and bias in health policy, healthcare financing, healthcare regulation, health professions training, healthcare innovation and healthcare practice, there is significant variation in the degree U.S. healthcare systems are responsive to the needs of socioeconomically and ethnically diverse patients with varying levels of HL. As such, the extent to which health systems demonstrate the attributes of HLHCOs reflects a structural determinant of health.

5.6. Healthcare Access and Quality

The depiction in Figure 5 underscores a flaw within the U.S. healthcare system where the patients who maximally benefit from health care often have the greatest capacity and resources, including but not limited to HL. In contrast, the healthcare system’s weaknesses are undergirded by issues related to access to care, including: incomplete and/or unequal health insurance coverage; unnecessary barriers to obtaining public insurance; overly complex health insurance practices; insufficient provider workforce for specific (underserved) populations; lack of a diverse healthcare workforce; under-valuing or under-resourcing primary care; and segregation of healthcare (including an obligatory over-reliance on overextended safety net health systems among vulnerable populations). There are additional features within many U.S. health systems that further undermine the quality of care and are particularly salient for disparity populations and patients with LHL. These include: inadequate preparation and training of the clinical workforce and associated poor provider performance (especially with respect to interpersonal processes of care); insufficient caregiver involvement and support; lack of ethnic and linguistic diversity in the workforce; lack of involvement of vulnerable populations in the design of healthcare services and its associated innovations; lack of peer and lay health educator models; lack of HL-appropriate digital health/e-health innovations; lack of resources and integrated interventions to assess and address social needs; fragmentation of healthcare; lack of inter-visit communication; incomplete trust in provider; and insufficient or inappropriate policies, regulatory standards, oversight, measurement and/or incentives to reduce disparities and promote healthcare equity [37–38].

5.7. Related Health Literacy Domains

Within the depicted healthcare pathway, HL is a product of HLHCOs as well as a potential asset that can positively influence the balance between HL-related demands healthcare systems place on patients and the HL-related skills of patients and families. The latter can mitigate the effects of receiving care in systems that are unresponsive to the needs of persons with LHL. Much has been studied and written about the patient-related HL skills required to optimally function within U.S. healthcare settings. These skills include communicative HL capabilities, such as: speaking; listening; reading and, increasingly, writing (e.g. secure messages in electronic patient portals) of health–related content; quantitative skills; e.g. health numeracy; and health insurance literacy - e.g. the ability to navigate bureaucratic procedures and advocate for oneself [39].

5.8. The Consequences

Overall, the lack of evolution and diffusion of the model of HLHCOs, combined with the fragmentation, overextension, and under-resourcing characteristic of many safety net healthcare systems (further compounded by a disproportionately high rate of LHL of the types described above among vulnerable patients), yields consequences for healthcare disparities - with respect to access, processes of care, and outcomes. The latter include: late presenting to medical attention - often with more advanced disease; demonstrating more missed appointments; poorer self-management skills; lesser degrees of patient activation; sub-optimal clinician-patient communication; less shared decision-making; lower trust; worse quality of care; and greater rates of medical error and patient safety events. The consequences of the depicted healthcare pathway, together with the public health pathway (which leads vulnerable populations to be even more reliant on healthcare because of a higher burden of disease) includes greater complication rates, worse health outcomes, higher costs of care and utilization of services, and greater premature morbidity and mortality.

6. Limited Health Literacy and Disparities in the Clinic Encounter: A Focus on the Communication Model

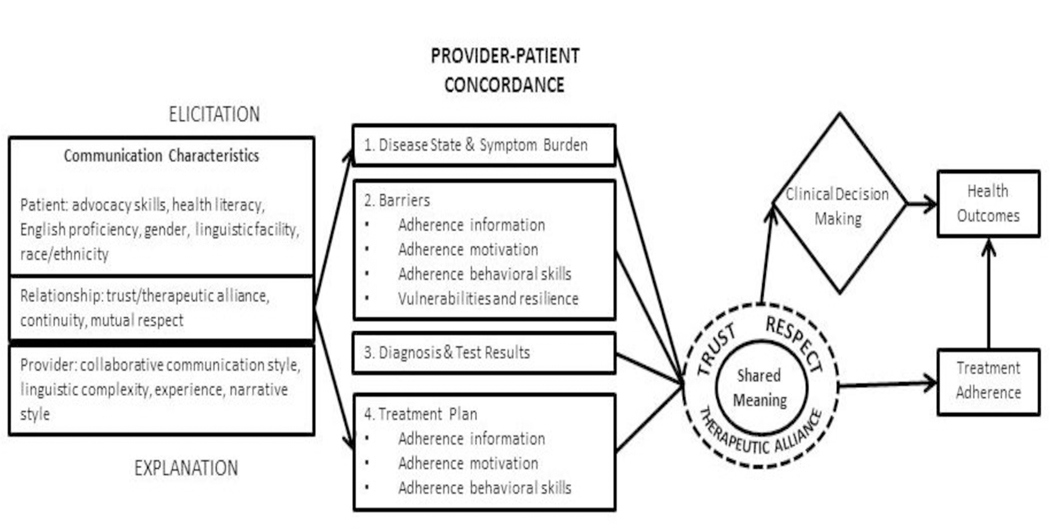

While a comprehensive framework for social determinants of health, HL and health disparities is presented in Figure 5, much of the HL research interested in understanding the contribution of LHL to healthcare disparities has focused on health communication issues. As a result, health communication is underscored in the healthcare pathway within Figure 6. Building on prior research, Schillinger and colleagues have described a model of communication within clinic settings, using the chronic disease management exemplar in ways that provide insights into HL and the emergence of healthcare disparities [39–40]. The model in Figure 6 shows how communication barriers such as limited HL (which are more common among populations subject to health and healthcare disparities) can impair the development of shared meaning along the path to achieving optimal health and wellbeing. More specifically, the pathway is: Patient HL and provider communication skills→ Effective elicitation and explanation→ Patient-provider concordance→ Shared meaning → Trust and therapeutic alliance → Appropriate clinical decision-making → Optimal treatment adherence → Health and well-being.

Figure 6.

Model for successful communication with vulnerable patients in the outpatient clinical encounter. (From: Schillinger D, et al. The Next Frontier in Communication and the ECLIPPSE Study: Bridging the Linguistic Divide in Secure Messaging. J Diabetes Res 2017)

The model in Figure 6 identifies the co-creation of ‘shared meaning’ as the most proximal, desired visit outcome [41]. This outcome attempts to achieve patient-clinician agreement in two domains: (a) elicitation domains, in which clinicians assess disease state and symptom burden and uncover barriers to adherence (including social vulnerabilities and resilience factors, as well as treatment-related preferences and value); and (b) explanatory domains, in which clinicians convey diagnoses and results and discuss treatment plans.

Achieving shared meaning within these domains requires that each party within a dyad employs a combination of communication skills and a commitment to the relational aspects of communication that are mutually reinforcing. Showing authentic interest in the patient as a whole person (e.g. noting you are curious about him or her beyond symptoms or illnesses) and coaching a patient into telling his or her story promotes disclosure of barriers and narrows social distance while fostering trust and a more therapeutic alliance with the patient, a more intermediate outcome.

In what is considered a benevolent cycle, the depicted therapeutic alliance engenders greater degrees of shared meaning - and greater degrees of shared meaning can enhance a therapeutic alliance. The interplay between the use of narrative approaches, the co-creation of shared meaning, and the deepening of the therapeutic alliance can improve clinical decision-making and resource acquisition, promote adherence, and enhance overall health – the more distal outcome. A collateral benefit is such relationship-centered care not only appears to reduce health disparities but also can enhance clinician well-being and serve as both a preventive measure against, and a tonic to, clinician burn-out [42].

7. Examples of HL Interventions Relevant to Health Disparities Reduction

The chapter now provides examples from the author’s practice-based intervention research to illustrate how the conceptual framework described in Figure 5 and Figure 6 inform the understanding of how the social determinants of health interact with HL to generate health disparities - as well as provide some insights regarding HL interventions.

The first example is related to the healthcare pathway noted in Figure 6. Schillinger, Bhandari, and Machtinger assessed the management of a common cardiac arrhythmia - atrial fibrillation - that is more prevalent in populations of low income and limited education [43–45]. Since this condition can foster clots to form in the heart and travel to the brain - resulting in a stroke -- it requires patients strictly adhere to an often complex medication regimen to thin the blood (an anticoagulant medication). Accurate anticoagulant control is critical to prevent stroke (a therapeutic effect) or prevent bleeding (a side effect). The investigators initially showed anticoagulant medication miscommunication was common; both LHL and Hispanic ethnicity were predictors of medication discordance and resultant poor anticoagulant control. However, enabling patients to communicate the anticoagulant regimen using a visual aid improved medication regimen concordance when compared to verbal communication. A subsequent intervention study involving patients in poor anticoagulant control suggested the use of a visual aid, when combined with a simple HL practice (one round of the teach-back method), when compared to usual care, was associated with a more rapid achievement of anticoagulant control, an effect observed only with those who misunderstood their regimen at baseline.

The second example relates to the public health pathway in Figure 5 and describes a public HL campaign to prevent type 2 diabetes (T2D) [46–47]. Once known as adult-onset diabetes, T2D is a significant epidemic that now affects children at alarming rates. During the last decade, T2D rates have tripled in American Indian youth, doubled in African American, and increased by 25–50% in Asian Pacific Islanders and Hispanic youth, and pre-diabetes rates have more than doubled across all ethnic groups. Public discourse predominantly frames T2D as a medical or individual behavioral problem, impeding progress on prevention. Steering attention to social and environmental forces can enable prevention efforts to gain traction.

The Bigger Picture campaign (TBP, thebiggerpictureproject.org) is a youth-generated campaign in the San Francisco Bay Area in which talented low-income youth and youth of color transform themselves from being targets of metabolic risk to agents of change by shifting conversations about T2D towards ‘the bigger picture;’ its social and environmental drivers. TBP merges the arts (spoken word) with public health to fuse youth’s understandings of T2D with their lived experiences. Poets powerfully advocate for positive social change to eliminate T2D in young people and in communities of color by crafting messages aligned with values held closely by adolescents. The messages resonate with teen peers and effect change, especially social justice and defiance against the social order.

TBP’s gifted artists and dynamic influencers create content that can motivate their peers to ‘take a stand against injustice,’ eliciting righteous anger and activation for civic engagement. Engaging in healthy behaviors, such as not consuming soda or junk food, or advocating for local policy change to make the healthy choice the easy choice, become ways to rebel against oppressive societal practices and structural forces that undermine health.

Moreover, TBP has observed impressive gains in both individual nutritional literacy and public HL - with youth showing a new understanding of ‘how health happens’ (e.g. the socio-ecological model) and a commitment to join the fight against T2D. TBP has won health and media/film awards; its efficacy is well-documented and its reach impressive (~2 million views); and its unique approach to fostering a culture of health among low-income youth, youth of color, and their stakeholders has contributed to local public health efforts to reduce health disparities. The latter efforts include the passage of a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages and an initiative to promote water consumption by installing filtered water stations in low-income communities.

8. Caveats Regarding Health Literacy as an Explanatory Factor in Health Disparities

To back up, the scientific endeavor combines unbiased experimentation with objective observations of the natural world to accumulate knowledge so as to approximate truth. However, while medicine is largely seen as a force for good, clinical science has a deeply checkered record of, at times, using its tools and its authority to promote or perpetuate inhumane policies and practices ranging from unethical research and medical practices which have harmed lower income and minority populations, to “racial hygiene” and race-based genocide.

When examining the question of whether and how HL affects health, researchers need to be mindful that literacy represents a resource which, for minority subgroups, historically has been withheld as a means to oppress, or has been measured and then used to judge groups as inferior or ineligible to participate as citizens as an alternate means to oppress [48]. There are several related challenges in HL research that researchers, policymakers and practitioners must be aware of that temper confidence in the validity of the research and its synthesis just presented, which encourage additional, complementary research to better approximate truth. The specific challenges of measurement and attribution are discussed in the remainder of this section.

To begin, there are diverse challenges associated with research measurement [49]. How best to measure patient HL - and whether or not HL measures are detecting true differences in capacities and skills in marginalized populations - can be problematic and controversial. A recent review of all HL research measures found that at least 51 unique measures have been created and employed, including a number in Spanish, with virtually all requiring paper and pencil responses, with individual measures requiring up to one hour to administer. Of the 51, 26 measured general HL, 15 measured disease or content-specific HL, and 10 measured specific sub-populations [50].

As previously described, health disparities are produced and perpetuated by multilevel forces operating at the individual, family, health system, community, and public policy levels that mutually reinforce each other to produce injustice and perpetuate inequity. Since conventional literacy assessments are bounded by cultural and linguistic assumptions derived from the dominant, majority population, more research is needed to assess patient HL in a comprehensive, holistic, and unbiased manner, and to expand the assessment of reliability and validity across sub-groups of interest in order to avoid misattributing health disparities solely to limited HL.

A clear, but by no means isolated example of this challenge is the use of HL measures that require proper pronunciation of medical terms to assess HL, such as the REALM (Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine). It is not hard to imagine that a measure in which a white researcher from a Northeast US institution scores a patient’s HL by determining whether a patient has read and pronounced a medical term correctly may lead to biased measurement. This is especially true if the subject is, for example, a black patient born in the southern U.S. whose pronunciation of some words in the English language may differ from that of the dominant or ‘mainstream’ linguistic culture, be that in medicine or any other field that involves both language and a pre-existing knowledge base [48]. The problem of cultural hegemony in literacy assessment, and the untoward downstream effects of related mis-measurement, is well elucidated in the social psychology field [51].

A second research challenge is attribution. The critique here is both general to social epidemiology and specific to HL research. For example, do the observations that LHL is more common is marginalized populations, and that in some cases observed social disparities in health outcomes appear to be (statistically) ‘explained’ by LHL suggest that the mediational relationship represents a causal pathway? There are alternative hypothesized mechanisms by which LHL may be associated with healthcare quality and health outcomes in research exploring the causes of health disparities among vulnerable population that are not causal [52]. These mechanisms include:

Confounds: LHL may simply be a marker for, or a result of socio-demographic and behavioral factors or life course exposures or experiences that by themselves directly or indirectly lead to morbidity and mortality. While most studies attempt to account for confounds using multivariable analytic methods, it is widely recognized that socio-economic variables obtained at one point in time (such as income) only incompletely capture income over the life course, or that income does not equate with assets and wealth. As such, residual confounding is not only possible, but is almost certain to exist. Similarly, while variables such as race or immigration status are often collected, these measures do not begin to capture the experience of being black or an immigrant in the U.S.

Reverse or cyclical causation: LHL may be a consequence of high disease burden or poor disease control, and thus associated with worse health trajectories (cyclical effect). In addition, individuals with longstanding T2D that is poorly controlled have been shown to experience worse cognitive function as a complication of the disease. In turn, this may contribute to the downward trajectory in self-management due to poor understanding - but it may be captured as LHL within a HL assessment, all occurring in a patient whose clinical course has already been largely determined.

Attention bias: What we choose to measure and what we choose not to measure inevitably influences inferences regarding cause and effect. LHL may affect outcomes through a demand-capacity mismatch, with the healthcare system placing inappropriate communication demands on patients; or communication resources are poorly distributed for the population with the greatest needs. The latter hypothesis suggests changes at the health system level provide intervention targets to mitigate health disparities related to LHL. While greater attention is finally being paid to the communication attributes of clinicians and healthcare organizations as they relate to patient HL, there has been little work to operationalize a measure of clinician or systems responsiveness to the needs of population with LHL [53]. This has hindered progress in reducing HL and racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare [49].

Attribution bias: Finally, insofar as literacy skills – be they HL or otherwise – reflect a resource that results from privilege and power, the absence of literacy reflects a particular manifestation of oppression and marginalization, be it historical or ongoing. Following this argument, those with LHL have inexorably been exposed to other forms of systematic deprivation - including forms of inter-generational oppression that are difficult or impossible to measure at the individual level. In this case, LHL - despite consistently demonstrating statistically significant meditational relationships - presents itself as an overly simplistic, stereotype-laden, and potentially dangerously false explanation for observed health disparities.

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

Limited HL is more common in populations who are socially disadvantaged, and there is a growing body of research to suggest that LHL may be an explanatory factor in pathways that generate health disparities. To better understand the potential mechanisms whereby LHL can mediate health disparities resulting from the social determinants of health, this chapter presents a novel conceptual framework that can inform research, policy, and practice for those interested in promoting health equity in the U.S.

The framework describes two primary pathways that generate consequences for health outcomes. The first operates through multi-level factors related to the unequal distribution of resources and exposures, and their related environmental and public health literacies. The second operates through underdeveloped institutional capacities of the health care systems, and related individual communicative literacies of the patients that rely on these systems. Both pathways emerge within a complex society characterized by competing forces that reflect both a history of marginalization and oppression of vulnerable sub-groups as well as a tradition of civic engagement and advocacy for progressive change that is the foundation of democracy. HL research - both descriptive and interventional - while still in its infancy, represents a progressive force whose objective and early achievements help reverse deeply ingrained policies, structures, and practices that create, perpetuate, or even amplify health disparities.

Nevertheless, when it comes to shedding light on the fundamental causes of health disparities, articulating mechanisms leading to health disparities, and intervening to promote health equity, HL research needs to evolve in at least six ways to achieve its promise. First, future research should focus on developing alternative HL measures that are not subject to bias and mismeasurement in marginalized populations - and should attend to ensuring the reliability and validity of these measures across population sub-groups. Second, more attention needs to be paid to comprehensively measure confounding variables, with a particular emphasis to avoid attribution bias. Third, since most HL research has focused on patients’ HL deficits; more work needs to operationalize a measure of clinician or systems’ responsiveness to the needs of populations with LHL, including the communication attributes of clinicians and healthcare organizations.

Fourth, descriptive research must be designed and powered to enable the simultaneous disentanglement of socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity (representative of all major ethnic subgroups) and limited English proficiency from HL, and to enable valid and informative meditational analyses, with a particular emphasis on longitudinal studies. Fifth, investment in interventional research must increase to: (a) ensure an ability to stratify effectiveness results by socio-demographic characteristics as well as by HL level; (b) enable exploration of interaction effects; and (c) include public HL interventions. Relatedly, a lack of differential effectiveness should not prevent the dissemination, uptake, and adoption of HL-appropriate interventions; rather, given the disproportionate burden of LHL in vulnerable populations, such interventions should be seen as an important means to reduce health disparities.

Finally, while making significant advances during the last twenty years, the field of HL research in the U.S. has involved a relative paucity of investigators from under-represented minority (URM) groups, groups that otherwise are very active in the field of health disparities research. This may be due, in part, to the inherent assumptions, biases and limitations that HL research to date suffers from, as described above. While there is a growing body of community-based participatory research in the field of HL, there remains a critical need to extend and enhance HL research by including the experience, voices, and intellectual capacity of a multidisciplinary cohort of URM researchers. Only by expanding inclusivity in this way will the field of HL be able to be optimally harnessed to reduce health and healthcare disparities.

Figure 2.

Percentage of adults in each health literacy level, by highest educational attainment (2003)

Figure 3.

Average health literacy scores of adults, by poverty threshold (2003)

References

- [1].Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health, The Lancet. 2008;372:1661–1669. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Braveman P. Monitoring equity in health and healthcare: a conceptual framework. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003;21(3):181–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Healthypeople.gov Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- [4].Frohlich KL, Potvin L, Frolich and Potvin. Frolich and Potvin respond. Am J Public Health. 2008: 1352–1352. DOI: 10.2105/ajph.2008.141309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Paasche-Orlow M, Parker R, Gazmararian J, Nielsen-Bohlman L, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005; 20(2):175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Health Literacy: A prescription to end confusion, Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Committee on Health Literacy. Google Books; DOI: 10.1056/nejm200503033520926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED493284. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- [8].Fleary SA, Ettienne R. Social disparities in health literacy in the United States, Health Lit Res Pract: 2019;3:e47–e52. DOI: 10.3928/24748307-20190131-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes. Gen Intern Med. 2004:1228–1239. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cavanaugh K, Huizinga MM, Wallston KA, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Davis D, Gregory RP, Fuchs L, Malone R, Cherrington A, Pignone M, DeWalt DA, Elasy TA, Rothman RL. Association of numeracy and diabetes control. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(10):1–53. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_policy_facpubs/172/. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- [12].Logan RA. Seeking an expanded, multidimensional conceptual approach to health literacy and health disparities research. Stud Health Techno Inform. 2017; 240:96–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mantwill S, Monestel-Umaña S, Schulz PJ, The relationship between health literacy and health disparities: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cooper L, Schillinger D. The role of health literacy in health disparities research In: Innovations in health literacy research: workshop summary. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2011:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bennett IM, Chen J, Soroui JS, White S. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7;204–211. DOI: 10.1370/afm.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Howard DH, Sentell T, Gazmararian JA. Impact of health literacy on socioeconomic and racial differences in health in an elderly population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:857–861. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sentell TL, Halpin HA. Importance of adult literacy in understanding health disparities, J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:862–866. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sarkar U, Karter AJ, Liu JY, Adler NE, Nguyen R, López A, Schillinger D. The literacy divide: health literacy and the use of an internet-based patient portal in an integrated health system—results from the diabetes study of Northern California (DISTANCE), J Health Commun. 2010;15:183–196. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Schillinger D, Barton LR, Karter AJ, Wang F, Adler N. Does literacy mediate the relationship between education and health outcomes? A study of a low-income population with diabetes. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:245–254. DOI: 10.1177/003335490612100305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bailey S, Pandit A, Yin S, Federman A, Davis T, Parker R, Wolf MS. Predictors of misunderstanding pediatric liquid medication instructions. Fam Med. 2009;41(10): 715–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Wallston KA, White RO, Rothman RL. Diabetes numeracy: an overlooked factor in understanding racial disparities in glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1614–1619. DOI: 10.2337/dc09-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wolf MS, Knight SJ, Lyons EA, Durazo-Arvizu R, Pickard SA, Arseven A, Arozullah A, Colella K, Ray P, Bennett CL. Literacy, race, and PSA level among low-income men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, Urology. 2006;68:89–93. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Wallston KA, Kripalani S, Elasy TA, Rothman RL, White RO. Health literacy explains racial disparities in diabetes medication adherence. J Health Commun. 2011;16:268–278. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Curtis L, Wolf M, Weiss K, Grammer L.The impact of health literacy and socioeconomic status on asthma disparities. J Asthma. 2012;49:178–183. DOI: 10.3109/02770903.2011.64829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gwynn KB, Winter MR, HJ Cabral, Wolf MS, Hanchate AD, Henault L, Waite K, Bickmore TW, Paasche-Orlow MK Racial disparities in patient activation: evaluating the mediating role of health literacy with path analyses. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:1033–1037. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Smith PC, Brice JH, Lee J. The relationship between functional health literacy and adherence to emergency department discharge instructions among Spanish-speaking patients. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104:521–527. DOI: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sentell T, Braun KL, Davis J, Davis T. Colorectal cancer screening: low health literacy and limited English proficiency among Asians and Whites in California. J Health Commun. 2013;18:242–255. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sentell T, Braun KL. Low health literacy, limited English proficiency, and health status in Asians, Latinos, and other racial/ethnic groups in California. J Health Commun. 2012;l17:82–99. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2012.712621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Schenker Y, Fernandez A, Sudore R, Schillinger D. Interventions to improve patient comprehension in informed consent for medical and surgical procedures. Med Decis Making. 2011;31:151–173. DOI: 10.1177/0272989X10364247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Seibert RG, Winter MR, Cabral HJ, Wolf MS, Curtis LM, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health literacy and income mediate racial/ethnic asthma disparities. Health Lit Res Pract. 2019:3:e9–e18. DOI: 10.3928/24748307-20181113-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, Cook E, Shaykevich S, Abbo ED, Lehmann L. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences, J Palliative Med. 2008;11:754–762. DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sperber NR, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ, Lindquist JH, Oddone EZ, Weinberger M, Allen KD. Differences in osteoarthritis self-management support intervention outcomes according to race and health literacy. Health Educ Res. 2013:28:502–511. DOI: 10.1093/her/cyt043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Karter AJ, Parker MM, Duru OK, Schillinger D, Adler NE, Moffet HH, Adams AS, Chan J, Herman WH, Schmittdiel JA. Impact of a pharmacy benefit change on new use of mail order pharmacy among diabetes patients: the diabetes study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Health Serv Res. 2015:50;537–559. DOI: 10.1111/1475-6773.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sudore RL, Schillinger D, Katen MT, Shi Y, Boscardin WJ, Osua S, Barnes DE. Engaging diverse English and Spanish-speaking older adults in advance care planning, JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178: 1616 DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Freedman D, Bess K, Tucker H, Boyd B, Tuchman A, Wallston K. Public health literacy defined. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/BPH_Ten_HLit_Attributes.pdf. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- [37].Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, Stewart A, Piette J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician–patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Edu Couns. 2004; 52:315–323. DOI: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Stepanikova I, Mollborn S, Cook KS, Thom DH, Kramer RM. Patients’ race, ethnicity, language, and trust in a physician. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;14:390–405. DOI: 10.1177/002214650604700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Schillinger D, McNamara D, Crossley S, Lyles C, Moffet HH, Sarkar U, Duran N, Allen J, Liu J, Oryn D. The next frontier in communication and the ECLIPPSE Study: bridging the linguistic divide in secure messaging, J Diabetes Res. 2017:1–9. DOI: 10.1155/2017/1348242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2004. DOI: 10.5860/choice.42-4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].McCabe R, Healey PGT. Miscommunication in doctor-patient communication. Top Cogn Sci. 2018;10: 409–424. DOI: 10.1111/tops.12337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schillinger D, Villeja T, Saba G. Creating a context for effective intervention in the clinical care of vulnerable patients. Medical Management of Vulnerable and Underserved Patients. 2007:67. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bhandari VK, Wang F, Bindman AB, Schillinger D. Quality of anticoagulation control: do race and language matter? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:41–55. DOI: 10.1353/hpu.2008.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Schillinger D, Wang F, Rodriguez M, Bindman A, Machtinger EL. The importance of establishing regimen concordance in preventing medication errors in anticoagulant care. J Health Commun. 2006; 11:555–567. DOI: 10.1080/10810730600829874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Machtinger EL, Wang F, Chen LL, Rodriguez M, Wu S, Schillinger D. A visual medication schedule to improve anticoagulation control: a randomized, controlled trial. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007; 33:625–635. DOI: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rogers EA, Fine SC, Handley MA, Davis HB, Kass J, Schillinger D. Engaging minority youth in diabetes prevention efforts through a participatory, spoken-word social marketing campaign. Am J Health Promot. 2017; 31:336–339. DOI: 10.4278/ajhp.141215-ARB-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Schillinger D, Tran J, Fine S. Do low income youth of color see “the bigger picture” when discussing type 2 diabetes: a qualitative evaluation of a public health literacy campaign. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018:15 DOI: 10.3390/ijerph15050840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Goldman D. The modern-day literacy test: felon disenfranchisement and race discrimination, Stanford Law Review. 2004; 57: 611. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schillinger D, Sarkar U. Numbers don’t lie, but do they tell the whole story? Diabetes Care. 2009; 32:1746–1747. DOI: 10.2337/dc09=1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Haun JN, Valerio MA, McCormack LA, Sørensen K, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health literacy measurement: an inventory and descriptive summary of 51 instruments. J Health Commun. 2014;19:302–333. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2014.936571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Harris VJ. African-American conceptions of literacy: a historical perspective. Theory Pract. 2010. DOI: 10.1080/00405849209543554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Schillinger D. Literacy and health communication: reversing the ‘inverse care law.’ Am J Bioeth. 2007;7:15–18. DOI: 10.1080/15265160701638553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Brach C, Dreyer BP, Schillinger D, Physicians’ roles in creating health literate organizations: a call to action. J Gen Int Med. 2014:273–275. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-013-2619-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]