Abstract

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a therapeutic style in which a provider elicits client motivation and helps strengthen commitment to change (Miller and Rollnick 2002). The original Family Check-Up (FCU; Dishion and Stormshak 2007)—and the adapted version for improving health behaviors in primary care, the Family Check-Up 4 Health (FCU4Health; Smith et al. 2018a)—are brief, assessment-driven, and family-centered preventive interventions that use MI to improve parent engagement in services to improve parenting and prevent negative child outcomes. This study examines the role of MI in the Raising Healthy Children project, a randomized trial to test the effectiveness of the FCU4Health for the prevention of obesity in pediatric primary care, with data from the 141 families assigned to receive the FCU4Health. Families were eligible for the study if the child was between 5.5 and 12 years of age at the time of identification and had a BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age and gender at the most recent visit to their primary care provider. MI skills at the first session predicted caregiver in-session active engagement, attendance at follow-up parenting sessions, and improvements in motivation to address child health and behavior goals. Baseline characteristics of the family (i.e., child health diagnosis, caregiver baseline depression, motivation, and Spanish language preference) had differential associations with responsiveness and MI skills. This study has implications for program development, provider training, and fidelity monitoring.

Keywords: Motivational interviewing (MI), Family Check-Up 4 Health, Participant responsiveness, Implementation science, Pediatric obesity, Culture

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a therapeutic style in which a provider attempts to encourage client motivation and strengthens commitment to change (Miller and Rollnick 2002). Specifically, it is a non-judgmental and directive approach that helps build motivation through empathetic and active listening, actively exploring a client’s ambivalence towards change, and supporting self-determinism and self-efficacy. Providers using MI ask open-ended questions to elicit client reasons for and against behavior change. They empathetically make reflective statements about these reasons in a way that encourages clients to engage in “change talk” (e.g., making intentions to change), which is a known precursor of behavioral change. It is considered an evidence-based practice that has been used to improve engagement in services for a variety of conditions, such as treatment of addiction and management of chronic illnesses, and settings, including primary care, emergency departments, and schools (e.g., DiClemente et al. 2017; Resnicow et al. 2004).

MI in Preventive Interventions

MI can play a critical role in promoting family engagement and success in preventive interventions as well. MI is a core component of the original Family Check-Up (FCU; Dishion and Stormshak 2007)—and the adapted version for primary care, the Family Check-Up 4 Health (FCU4Health; Smith et al. 2018a). The FCU and FCU4Health are brief, assessment-driven, and family-centered preventive interventions that use MI to increase parent engagement in services with the goal of improving parenting and preventing negative child outcomes. The original FCU and by extension FCU4Health were inspired by the Drinker’s Check-Up (Miller et al. 1988), the precursor to contemporary MI, which leverages the results of norm-based, self-reported drinking behaviors to motivate behavior change using MI techniques. The structure of both the FCU and FCU4Health programs includes (1) a comprehensive assessment using normed meaures of parenting, the family environment, health behaviors, and caregiver and child mental health, followed by (2) a feedback and motivation session, in which providers present the results of the assessment and use MI to support caregivers in developing a plan for follow-up support. The quantity, frequency, and content of follow-up services depend on families’ strengths, needs, and interests. Caregivers may be offered tailored parent training sessions using the Everyday Parenting curriculum (Dishion et al. 2011), which includes 12 modules that address positive behavior support, limit setting, and relationship building. To address non-parenting needs, providers help connect parents with existing community-based resources.

Adaptation for Primary Care

Randomized trials have confirmed effects of the original FCU on child conduct problems and adolescent risk behavior, which are mediated by effects on targeted parenting behaviors, such as monitoring, positive behavior support, and involvement (Dishion et al. 2008). Although not explicitly targeted by the program, several studies found that the FCU produced collateral effects on obesity and health behaviors, mediated by improvements in parenting (Smith et al. 2015; Van Ryzin and Nowicka 2013). Based on these findings and input from community stakeholders, the FCU was formally adapted to target physical health in integrated primary care-behavioral health settings (Berkel et al. 2020; Smith et al. 2018a). The resulting FCU4Health program has additional health-related content, but the structure is similar to the original FCU (for details, see “Methods” section). Most importantly, the FCU4Health retains the FCU’s reliance on MI techniques to promote behavior change, which is important given the ambivalence many caregivers have with respect to child obesity. On the one hand, health behaviors are difficult to change, and caregivers face many barriers in terms of time and resources. On the other hand, caregivers care about their children’s health and want to follow their pediatrician’s recommendations. Unfortunately, stigmatizing language commonly used in healthcare settings can reduce motivation to improve children’s health (Puhl et al. 2011). However, MI is designed to leverage motivation towards change and overcome potential stigma, improving engagement in services (Pakpour et al. 2015) and health outcomes (Resnicow et al. 2015). Moverover, MI has been found to reduce stigma in other settings, such as treatment for substance use disorder (Livingston et al. 2012).

Fidelity to MI

Given that MI skills are often distinct from the way that providers typically attempt to promote behavior change (i.e., providing advice and information), ongoing fidelity monitoring to MI is critical (Kimber et al. 2017). The COACH observational rating system was developed to monitor the implementation of the FCU (Dishion et al. 2014) and is also used for FCU4Health. The COACH assesses five dimensions of observable provider skill: maintaining Conceptual accuracy to the model, being Observant and responsive to client needs, Actively structuring sessions, Careful teaching and feedback, and fostering Hope and motivation. Previous studies demonstrate a link between COACH ratings and parent in-session engagement, and in turn, longitudinal improvements in parenting and child behaviors (Chiapa et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2019).

Given that MI plays a central role in the FCU and FCU4Health, many of the behaviors assessed in the COACH map on to MI skills as described by Miller et al. (1992) to promote client motivation and engagement. Each dimension of the COACH includes prescribed and proscribed behaviors for coders to consider in the assessment of that dimension. For example, Conceptual Accuracy includes “Follows FCU4Health protocol in structure and content of session” (prescribed), “Offers a menu of evidence-based services that address family’s specific needs” (prescribed), and “Delves into tangents or engages in speculations that are NOT evidence-based” (proscribed). Hope and Motivation includes “Prompts, evokes, and supports change talk” (prescribed), “Instills hope by identifying strengths and reflecting on previous successes” (prescribed), and “Advice giving, disagreement, or teaching in the face of ambivalence or discord” (proscribed). In combination, these two dimensions of the COACH reflect MI skills in that they encompass providing personal feedback, supporting self-motivational statements, and developing a plan that makes use of evidence-based approaches (Miller et al. 1992). Furthermore, in combination, these domains address both the fidelity to the program content and competent process quality, which have been shown to be important components of successful program delivery (Durlak and DuPre 2008). Smith et al. (2019) conducted analyses to determine the relative importance of the COACH dimensions and found that Conceptual Accuracy and Hope and Motivation differentiated providers with varying levels of training in the FCU (higher vs. lower vs. no training), compared to the other three dimensions. Their findings indicate the distinctiveness of these skills from general therapeutic processes.

Theoretical Model

Implementation is a complex and multidimensional construct (Durlak and DuPre 2008). Berkel et al. (2011; 2018) proposed a theoretical implementation cascade model where indicators of participants’ responsiveness to the program (e.g., attendance, in-session active engagement, home practice of program skills) mediate the influence of providers’ delivery (i.e., content and process) on program effectiveness. The current study examines the role of MI in a randomized trial to assess the effectiveness of the FCU4Health on the prevention of excess weight gain and its implementation in pediatric primary care settings (Smith et al. 2018b). In accordance with the implementation cascade model (Berkel et al. 2011, 2018), we test the effects of providers’ delivery of MI on multiple dimensions of responsiveness that are theoretically linked with MI. First, we attempt to replicate findings from the original FCU demonstrating a link between provider fidelity to MI skills during the first feedback session and caregiver in-session active engagement (Smith et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2019). Second, we examine whether MI skills predict participation in follow-up parenting sessions. Previous studies have demonstrated that improvements in parenting are the primary change mechanism linking the FCU to improvements in a host of child outcomes (e.g., Brennan et al. 2013; Caruthers et al. 2014; Dishion et al. 2003; Smith et al. 2015; Van Ryzin and Nowicka 2013), indicating empirical support for Everyday Parenting sessions as a core component of the FCU and FCU4Health. Third, we examine whether MI influences caregivers’ follow-through on referrals to community resources, which have not been tested in previous studies, but is a theoretical core component of the program. Finally, we examine the effect of MI skills on caregivers’ motivation to achieve goals related to child health and behavior. In a randomized trial of the original FCU with middle school students, caregiver motivation to change explained variability in improvement in adolescent problem behavior (Fosco et al. 2014).

Predictors of MI

In addition, MI draws attention to baseline motivational factors that may influence program engagement and effectiveness. Fosco et al. (2014) found that caregiver depression and minority status predicted improvements in FCU outcomes, mediated by motivation to change. Depression is a well-established risk factor for challenges both in parenting (Downey and Coyne 1990) and engagement in mental health treatment (Kohn et al. 2004), particularly for Latinos and African Americans (Alegría et al. 2002). However, results have been mixed for the effect of caregiver depression on engagement in parenting interventions, with some studies finding that depressed parents were less likely to engage and others finding no effect (e.g., Baker et al. 2011; Baydar et al. 2003). With respect to the original FCU, caregiver depression was part of a constellation of parenting stress measures that predicted increased engagement in services over an 8-year period (Smith et al. 2018c).

With respect to cultural influences on engagement in parenting interventions, previous research has demonstrated that less acculturated, Spanish-speaking caregivers were more engaged in a group-format parenting program than more acculturated, English-speaking caregivers (Dillman Carpentier et al. 2007). Latino cultural values that emphasize the role of the family and support positive and tight-knit interpersonal interactions may reinforce engagement in parenting programs, particularly when they are delivered in a group setting. It is unknown whether similar effects for engagement would be seen in an individually tailored intervention like the FCU4Health that is delivered one-on-one. Furthermore, MI relies to a large extent on linguistic processes (e.g., open questions, reflective statements). Although MI appears to be culturally appropriate (Añez et al. 2008), we are unaware of any studies that compare MI skills across language.

Finally, child health status may play a role in caregiver responsiveness to the FCU4Health. Concerns about children’s health have been identified as an important contributor to caregiver engagement in pediatric obesity programs (Farnesi et al. 2019). Caregivers may feel pressure from pediatricians, who recommend difficult changes to family routines (Berkel et al. in press). Because FCU4Health focuses on physical health, while simultaneously retaining the focus on behavioral health, diagnoses related to both behavioral and physical health may be associated with responsiveness to the program. Based on previous research, we propose that these baseline characteristics influence caregivers’ steps to improve their children’s health. However, the question remains as to whether they may also influence providers’ ability to deliver MI in the FCU4Health. MI is designed to meet clients at any stage of change to help them move to the next level, and yet, it is plausible that more motivated clients are more engaging to work with. Client enthusiasm or progress toward goals, for example, may be rewarding for providers, and reinforce their use of MI.

The Current Study

This study examines the role of MI as a theoretically based core component in promoting multiple aspects of participant responsiveness in the Raising Healthy Children randomized trial of the FCU4Health, which includes an ethnically diverse sample of families with children who have elevated BMI. Specifically, we test the process theory that MI at the first feedback session is associated with in-session engagement and predicts attendance at parenting sessions, follow-through on referrals to community resources, and movement along the stages of change continuum. We further examine baseline characteristics of families (i.e., depression, culture, and health status) as predictors of MI skills and participant responsiveness.

Methods

The Family Check-Up 4 Health Program

The FCU4Health has a similar structure to the original FCU, but with additions made to the content to address physical health behaviors (Smith et al. 2018a). The structure includes (1) a comprehensive assessment, (2) a feedback and motivation session, and (3) follow-up services that include modules from the Everyday Parenting curriculum (Dishion et al. 2011) and connections with community-based resources. In FCU4Health, the assessment was expanded to include validated health measures (e.g., Family Health Behavior Scale: Moreno et al. 2011) and parent-child observation tasks focused on child health goals and caregiver awareness of health guidelines. In the feedback and motivation session, the FCU4Health provider, referred to as a “coordinator,” presents the results of the assessment and discusses with the caregiver how positive parenting and regular health routines can influence their child’s physical and behavioral health. Follow-up parenting modules focus on how to use parenting skills to improve child physical health behaviors (e.g., monitoring sleep habits, setting limits on screen time). Referrals to community resources focus on addressing social determinants of health (e.g., food insecurity) and specialty health problems associated with excess weight (e.g., asthma). FCU4Health coordinators in this trial held, or were in training for, postgraduate degrees in such areas as behavioral health, social work, public health, exercise science, and health promotion, with experience working with caregivers and families ranging from 2 to more than 15 years.

Study Procedures

The Raising Healthy Children project is a randomized type II hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial of the FCU4Health program for the prevention of excess weight gain in primary care clinics (Smith et al. 2018b). The study took place in the Phoenix metropolitan area. Referrals to the study were made by five pediatric primary care organizations, four of which were federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), and the fifth was an outpatient primary care clinic within a large children’s hospital. Participants were primarily identified for the study during well- and sick-child appointments by primary care providers or behavioral health consultants. Families were eligible for the study if the child was between the ages of 5.5 and 12 years of age at the time of identification, had a BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age and gender at the most recent visit to their primary care provider, and had a primary caregiver who was available to participate. No other exclusion criteria were used.

Enrolled families completed surveys at study entry. They were administered electronically with support from an interviewer (a clinic community health worker employed by the referring clinic or a study staff member) in a location of the family’s choice (i.e., the family home, the clinic, or other community location with sufficient privacy). Primary caregivers, children, and secondary caregivers responded to questions examining family health behaviors, parenting, child adjustment, and social determinants of health. Portable electronic scales with bioelectric impedance technology were used to assess weight and body composition of target children, caregivers, and any other family members who were present and interested. Last, the caregivers and children participated in brief, videotaped, semi-structured family interaction tasks for subsequent rating of parenting skills, child behavior, and knowledge of health guidelines by trained coders. Batteries were conducted either in English or Spanish, based on the preference of the family. Families were assessed again at 3-month (mid-point), 6-month (post-test), and 1-year (long-term) follow-ups. Families were compensated $40 at baseline, $25 at the 3-month, $30 at the 6-month, and $55 at the 1-year follow-up for completion of the assessment. No incentive was given for participation in feedback or follow-up sessions.

After completing the baseline assessment, families were randomized to the FCU4Health program (n = 141) or usual care (n = 99). Randomization was unbalanced at a ratio of 7:5 to provide more implementation-related data. In accordance with the US Preventive Services Task Force (2017) guidelines recommending 26–50 contact hours in a 6-month period to address pediatric obesity, the FCU4Health was offered to intervention families in a condensed health maintenance model. Specifically, intervention families completed a feedback session after the baseline, 3-month, and 6-month assessments. The first feedback session began with a discussion to understand caregivers’ perception of their needs and motivation to change parenting in support of health behavior change. The second and third feedback sessions began with a check-in with the family about their progress, any barriers they may have experienced, and how previous sessions may or may not have been helpful. The Everyday Parenting curriculum includes 12 parenting modules. These modules were offered to the families based on their interests after the first and second feedback sessions. Referrals to community resources (e.g., nutrition, physical activity, social services, specialty health/mental health) were made as needed between the first and third feedback sessions. At the third feedback session, an attempt was made to ensure families were linked with a community resource that could provide ongoing support as needed.

Participants

As this study is focused on implementation processes, only families in the intervention condition are included in the analyses (n = 141). At baseline, child mean age was 9.5 (1.9) years. Child gender distribution was roughly equal, with 73 (52%) male and 68 (48%) female participants. Caregiver gender was predominantly female (n = 130; 92%). Children’s racial/ethnic background was: 92 (65%) Latino, 20 (14%) non-Latino White, 9 (6%) Black/African American, 4 (3%) American Indian/Alaska Native, 2 (1%) Asian, and 11 (8%) multiple racial/ethnic categories. Caregivers’ racial/ethnic background was: 96 (68%) Latino, 20 (14%) non-Latino White, 7 (5%) African American, 5 (4%) American Indian/Alaska Native, 3 (2%) Asian, and 7 (5%) multiple racial/ethnic categories. Three caregivers chose not to respond to race/ethnicity questions. Concerning language, 88 (62%) caregivers elected to complete baseline assessments in English and 53 (38%) in Spanish. Mean child BMI was 115.6% above the 95th percentile (SD = 22.0).

Measures and Coding Procedures

MI Ratings

The COACH rating system (Dishion, Smith, et al. 2014) was used to rate fidelity to the FCU4Health feedback session protocol at the first feedback session. The COACH assesses five dimensions of observable coordinator skill in the FCU4Health, which are rated separately on a 9-point scale: 1–3 (needs work), 4–6 (competent work), 7–9 (excellent work). In this study, we focused on Conceptual Accuracy and Hope and Motivation, as these are most reflective of MI skills, as described above. Coders were four family interventionists with training in the FCU4Health and experience delivering the program to families in the trial. Three bilingual coders were assigned sessions in Spanish and English, whereas one monolingual English coder was assigned only sessions in English. Coders were not assigned sessions they had implemented. They received approximately 20 h of training in the COACH, which included rating feedback sessions as a group with one of the FCU4Health developers (JDS) and then independently rating 3–5 sessions to determine reliability. The reliability criterion at the conclusion of training requires scoring three sessions in a row with 85% agreement with gold standard ratings. As was the case in previous trials, “agreement” was achieved if raters’ scores were within one point of the gold standard on each dimension. Once the reliability criterion was met, the coders were assigned sessions and attended bi-weekly meetings to maintain reliability and minimize coder drift. Coders first reviewed the assessment results to establish familiarity with the family and develop a case conceptualization. This step has been shown to improve reliability (Smith et al. 2016). Coders then viewed the entire FCU4Health feedback session. To calculate interrater reliability, 20% of the sessions were randomly selected for independent rating by two different members of the team. The same 1-point criterion was used to calculate percent agreement between coders. Agreement was good for Conceptual Accuracy (79%), Hope and Motivation (69%), and a mean score of the two dimensions (74%), which was used in the final analysis.

In-Session Engagement

Coders also rated caregivers’ in-session engagement at the first feedback session as: 1–3 (low, caregiver is inattentive or disengaged), 4–6 (medium, modest signs of engagement), and 7–9 (high, caregiver actively participates and is attentive and responsive). As with the COACH dimensions, the engagement dimension includes participant behaviors that reflect positive and negative indicators of engagement, including “Engages in ‘change talk’ by reflecting on the past and future” (positive), “Actively participates, nods head, and stays on topic during feedback” (positive), and “Angry or defensive during feedback session” (negative). Interrater reliability for the caregiver engagement item has been fair to excellent in previous studies (Chiapa et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2019). Agreement in this study for caregiver engagement was 73%.

Parenting Sessions and Referral Outcomes

The FCU4Health activities checklist (FACL) was adapted from a form used in the original FCU trials (Winter and Dishion 2007) to capture administrative data used as part of program delivery. This form included participation in Everyday Parenting modules and outcomes of referrals to community resources. Because of the variability in need for referrals, we calculated this as a dichotomous variable that reflected whether the family accessed the resource and needs were met.

Motivation

At each wave, caregivers reported on their motivation to achieve seven goals for their families. Three of these goals, related to parenting and family dynamics, were taken from the original FCU (Fosco et al. 2014). Four new goals that relate to child health behaviors (e.g., nutrition, physical activity, sleep, and screen time) were added for the FCU4Health. Parents rated each of these goals on a 5-point scale with anchors informed by the transtheoretical model (Prochaska and DiClemente 1983): 1 = no change needed, 2 = thinking about change, 3 = wanting to change, 4 = taking steps to change, and 5 = working hard to change. Cronbach’s α for the full 7-item scale was 0.89 at baseline and 0.91 at post-test. We also conducted paired samples t tests to determine whether there were differences in ratings of health versus behavior at baseline and post-test. No significant differences were found at either timepoint.

Depressive Symptoms

Caregivers reported on depressive symptoms with the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Radloff 1977). Sample items included “I felt depressed” and “I felt that everything I did was an effort.” Cronbach’s α was 0.95.

Health Diagnoses

Diagnosis codes were extracted from clinic electronic health records (EHR). We documented whether children had a diagnosis that fell under the category of “endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases” or “mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders.”

Demographics

At baseline, caregivers reported on demographic characteristics, including children’s and their own age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Although many of the families were bilingual, caregivers were given the choice of responding to the assessment in English or Spanish. Their choice was used as a dichotomous indicator of language preference in this study.

Analytic Strategy

We began by testing the correlations between all study variables. Study hypotheses were tested in Mplus 8.1 (Muthén and Muthén 2018) using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (Enders and Bandalos 2001). Families were nested within coordinator to account for non-independence. Demographic variables (i.e., child age and parent and child racial/ethnic background and gender) were individually tested as covariates and were dropped from the model if not significant. Baseline motivation was included as a covariate for analyses testing effects on post-test motivation. Paths from baseline characteristics to MI and responsiveness indicators were dropped for parsimony if not significant. We determined good model fit as indicated by a non-significant X2 or a combination of SRMR close to 0.08, RMSEA close to 0.06, and CFI close to 0.95 based on simulation studies that revealed using this combination rule resulted in low type I and type II error rates (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Results

Descriptive information and correlations between study variables are presented in Table 1. On average, MI skills and parent engagement were assessed to be at the midpoint of the respective scales, and the high and low limits of scales were not used (range: Conceptual Accuracy = 2–7; Hope and Motivation = 2–7; Engagement = 3–8). Families engaged in a mean number of 2 parenting sessions. Nearly all (92%) families connected with community resources to address their contextual needs. Parents rated their motivation to achieve goals related to child health and health behavior at the midpoint of the scale at baseline and post-test.

Table 1.

Correlations and descriptives of study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||||||||||

| 1. Metabolic Dx | – | ||||||||||

| 2. Behavioral Dx | − 0.04 | – | |||||||||

| 3. Motivation | 0.13 | − 0.00 | – | ||||||||

| 4. Depression | − 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.18* | – | |||||||

| 5. Spanish language | − 0.12 | − 0.08 | 0.01 | − 0.28*** | – | ||||||

| Implementation | |||||||||||

| 6. Conceptual Accuracy | − 0.02 | 0.21* | 0.02 | − 0.02 | − 0.11 | – | |||||

| 7. Hope and Motivation | − 0.01 | 0.24** | − 0.13 | − 0.12 | − 0.14 | 0.66*** | – | ||||

| 8. In-session engagement | 0.16+ | − 0.09 | 0.06 | − 0.22* | − 0.10 | 0.32*** | 0.34*** | – | |||

| 9. Parenting modules | − 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.05 | – | ||

| 10. Referral outcomes | 0.01 | 0.02 | − 0.18+ | − 0.23** | − 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.21* | 0.23* | – | |

| Post-test | |||||||||||

| 11. Motivation | 0.19+ | 0.01 | 0.52*** | 0.17 | − 0.15 | 0.30** | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.27* | 0.22+ | – |

| Mean/% | 21.3 | 12.8 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 37.6 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 1.7 | 92.0 | 9.2 |

| SD | – | – | 1.1 | 0.8 | – | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 2.3 | – | 1.2 |

p ≤ 0.001;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.05;

p < 0.10

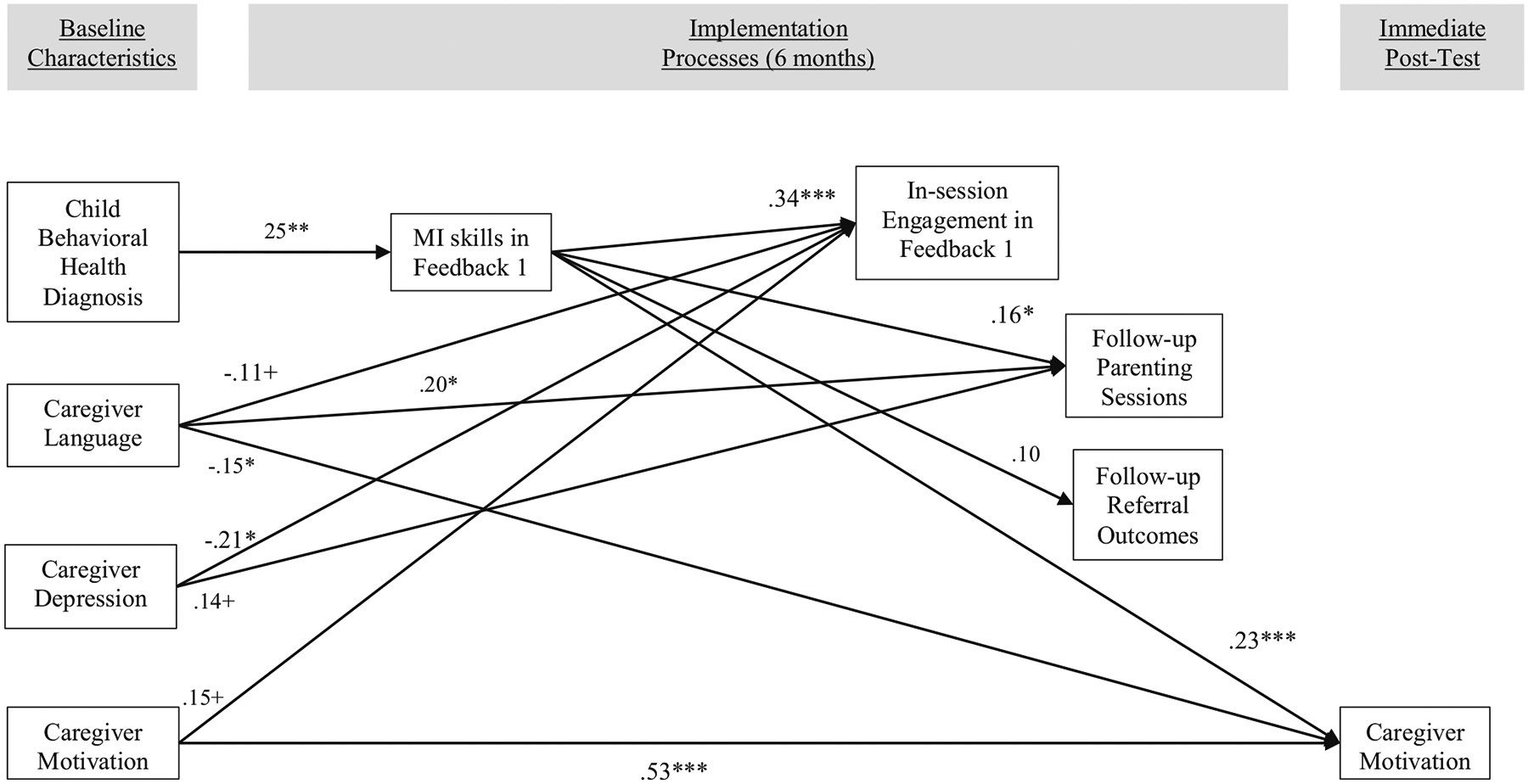

A non-significant chi-square [X2(15) = 20.48, p = 0.15] indicated good fit to the data (see Fig. 1). Covariates (i.e., child age, caregiver and child gender and ethnicity) were not included in the final model due to lack of significance. MI skills in the first feedback session were associated with in-session engagement (β = 0.34, p ≤ 0.001). They predicted the number of follow-up parenting sessions attended (β = 0.16, p = 0.05), but the effect on referral follow-through was not significant. MI skills predicted improvements in motivation over time (β = 0.23, p ≤ 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Results of the Theoretical Model

Note. X2 (15) = 20.48, p = .15; *** p≤.001; ** p≤.01; *p≤.05; +p<.10

With respect to baseline predictors, Spanish language preference was associated with more participation in parenting sessions (β = 0.20, p = 0.02), but there was a trend for lower ratings on in-session engagement (β = −0.11, p = 0.099). Spanish language also predicted decreases in caregiver motivation over time (β = −0.15, p = 0.02). Baseline motivation played a limited role, with only a trend for an association with in-session engagement (β = 0.15, p = 0.07). Caregiver depression was negatively associated with in-session engagement at the initial feedback session (β = −0.21, p = 0.03), but there was a trend for a positive association with attendance at follow-up parenting sessions (β = 0.14, p = 0.06). The child having a behavioral health diagnosis was the only baseline characteristic that predicted the coordinator’s use of MI skills (β = 0.25, p = 0.01).

Discussion

Although decades of evidence demonstrate the potential of family-focused preventive interventions to improve public health, these effects have not been achieved (O’Connell et al. 2009), in part due to challenges in engaging families in services (Mauricio et al. 2018). Motivational Interviewing (MI) shows great promise for addressing these challenges and has spread globally to address multiple health conditions, in both preventive and treatment contexts (Miller and Rollnick 2009). This study was conducted to examine the effects of MI skills on engagement in the Family Check-Up 4 Health (FCU4Health) program to address pediatric obesity in integrated primary care. Providers’ use of stigmatizing language about obesity limits parents’ engagement in care (Brewis 2014). Given that MI specifically targets motivation, we surmised that the FCU4Health’s inclusion of MI strategies would be particularly important for engaging caregivers to address this pervasive health concern. Results of this study confirmed the importance of MI skills during the family’s first feedback session in engaging families in multiple components of parenting intervention focused on health behaviors. Using multiple data sources (i.e., observational, coordinator report, caregiver report, and EHR), we found that observational ratings of MI skills were associated with multiple indicators of responsiveness that were captured at timepoints across the intervention, spanning from the initial session to immediate post-test.

The quality of MI skills (using the Hope and Motivation and Conceptual Accuracy dimensions of the COACH rating tool) at the first feedback session was associated with parents’ active engagement during the session. This is consistent with the results of research on the original FCU, in which COACH ratings were correlated with caregivers’ observed in-session engagement (Smith et al. 2013). It should be noted that the mean fidelity scores found for the two COACH dimensions in this study (M = 4.4, SD = 1.0) are comparable to an effectiveness trial of the original FCU (M = 4.5, SD = 1.05), but are slightly lower than FCU efficacy trials that had mean scores around 5.0 (Chiapa et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2016).

MI skills predicted the total number of parenting sessions attended during the 6 months of the program. While previous research has shown that process quality is associated with attendance in parenting interventions (Berkel et al. 2018), the FCU and FCU4Health are somewhat unique in that there is no prescribed number of parenting sessions that families should receive. Rather, the dosage is driven by the level of need. The finding that MI skills drove the number of sessions may reflect a higher level of need in the sample or simply that caregivers were more willing to meet with coordinators who were more skilled with MI. It is also useful to note that the average number of sessions attended in this study was higher than previous studies (Smith et al. 2018c); perhaps indicating a higher level of risk in this sample.

MI skills also predicted increases in caregiver-reported motivation to change from baseline to the immediate post-test. Parent motivation plays an important role in MI-based interventions like the FCU and FCU4Health, and it has been empirically demonstrated to be an important mediator of program effects (Fosco et al. 2014). These findings validate the role of MI skills in promoting parents’ motivation to address child outcomes. Given the adaptation of the program to focus on health behaviors, it was also useful to examine any differences between the two types of goals: those directed at improving children’s behavioral health (from the original FCU) and those focused on physical health (added for the FCU4Health program). Interestingly, parents reported equal motivation to improve children’s behavioral health and physical health. This finding is important to the delivery of programs like the FCU4Health in integrated primary care settings where both physical health and behavioral goals can be addressed (Kwan and Nease 2013).

Finally, we assessed the role of family baseline characteristics in providers’ delivery of MI skills and on responsiveness indicators. Previous research has demonstrated that less acculturated, Spanish-speaking families were more likely to participate in a group-format parenting program (Dillman Carpentier et al. 2007). This effect was attributed to cultural values that have an origin in Latin American countries, but may diminish over generations in a more individualistic country like the USA (Knight et al. 2011). Familismo emphasizes the family as a primary organizational structure for daily life—it provides a sense of identity and support, as well as relational obligations. In this way, the explicit focus on families among parenting interventions, like the FCU and FCU4Health, is particularly salient for Latino communities. Personalismo has been used to describe the emphasis on warm, empathetic interpersonal relationships, which can lead to close relationships and trust (confianza) with providers and other participants in a group-based program and can reinforce participant responsiveness. However, the one-on-one delivery format in the FCU and FCU4Health may be less appealing than group delivery. In addition to cultural values are practical issues—specifically, there are fewer programs available for Spanish-speaking families.

Consistent with Dillman Carpentier and colleagues, we found that Spanish-speaking caregivers were in fact more likely to attend follow-up parenting sessions. Unfortunately, we were not able to measure cultural values directly, so it is unknown whether this was driven by cultural values or practical issues. This should be examined in future research. Unexpectedly, we found that Spanish language predicted a decrease in motivation over time. This unanticipated result will require additional investigation in future research. Finally, because MI is to a large extent linguistically based (e.g., open questions, reflective statements) and developed by English speakers, we also explored whether it may be more challenging to deliver MI in Spanish. Ratings in the current study indicated that providers were equally proficient in Spanish and English.

In terms of motivation and health status, results were mixed. Baseline motivation to improve parenting and health behaviors played only a moderate role in understanding participants’ responsiveness to the program. Caregiver depression, which is linked with motivation, was negatively correlated with in-session engagement and referral outcomes. Some previous studies have found a positive association between baseline depression and engagement (Smith et al. 2018c), whereas others have found no association (Baker et al. 2011). Children’s metabolic and behavioral health diagnoses, on the other hand, were not associated with any aspects of responsiveness. We expected that a formal diagnosis, which is often accompanied by the pediatrician’s strong encouragement for action, would be associated with greater levels of participant responsiveness. However, this effect may have been attenuated by the fact that all children were referred to the study on the basis of a health concern (BMI).

The limited effect of baseline characteristics on MI skills is evidence that MI can be used to support clients at any stage of change. However, it is also plausible that clients who are more motivated may be more receptive to these techniques, and consequently, may reinforce to a greater extent providers’ use of MI. The fact that baseline stage of change was unrelated to MI skills means that regardless of parents’ initial motivation, providers were equally able to use MI skills to help them move forward. The only baseline characteristic that predicted MI skills was child behavioral health diagnosis. As all children in the study had elevated BMI, this group would be considered to have a comorbid behavioral health condition. Thus, it appears that providers made better use of MI skills for children with comorbid physical and behavioral health concerns, which would make them a highly appropriate population for integrated primary care settings. On the other hand, given the COACH was originally designed to assess fidelity to a behavioral health intervention, it may also indicate that the coding system is more in tune with behavioral health concerns. Future work will examine whether this may be the case.

This study has a number of limitations to acknowledge. First is the indicated sample (children with elevated BMI), which may limit generalizability. As in previous research with the COACH, ratings of MI and of caregiver engagement are concurrent and by the same coder, which may increase the correlation between these ratings (Smith et al. 2013). Finally, the study was not sufficiently powered to assess whether baseline characteristics moderated the effect of MI skills on responsiveness outcomes. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literature on MI by demonstrating the links between MI skills, multiple indicators of responsiveness, and baseline family characteristics in the context of a parenting program for obesity prevention in primary care.

Funding Information

This study was supported by the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U18 DP006255; Berkel and Smith).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Berkel and Smith co-developed the Family Check-Up 4 Health program with Thomas Dishion, developer of the original Family Check-Up.

Ethical Approval This trial was designed in accordance with the basic ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, justice, and non-maleficence and conducted in accordance with the rules of Good Clinical Practice outlined in the most recent Declaration of Helsinki. The project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Arizona State University (Protocol 00004530) and Phoenix Children’s Hospital (Protocol 17–001). All other institutions participating in this research provided signed reliance agreements ceding to the IRB of Arizona State University.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Alegría M, Canino G, Ríos R, Vera M, Calderón J, Rusch D, & Ortega AN (2002). Mental health care for Latinos: inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and Non-Latino Whites. Psychiatric Services, 53(12), 1547–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Añez LM, Silva MA, Paris M, & Bedregal LE (2008). Engaging Latinos through the integration of cultural values and motivational interviewing principles. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(2), 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Baker CN, Arnold DH, & Meagher S (2011). Enrollment and attendance in a parent training prevention program for conduct problems. Prevention Science, 12(2), 126–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Reid MJ, & Webster-Stratton C (2003). The role of mental health factors and program engagement in the effectiveness of a preventive parenting program for Head Start mothers. Child Development, 74(5), 1433–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Gallo CG, & Brown CH (2018). The cascading effects of multiple dimensions of implementation on program outcomes: a test of a theoretical model. Prevention Science, 19(6), 782–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, & Sandler IN (2011). Putting the pieces together: an integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science, 12(1), 23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Rudo-Stern J, Abraczinskas M, Wilson C, Lokey F, Flanigan E, Villamar JA, Dishion TJ, & Smith JD (2020). Translating evidence-based parenting programs for primary care: Stakeholder recommendations for sustainable implementation. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(4), 1178–1193. 10.1002/jcop.22317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan LM, Shelleby EC, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Dishion TJ, & Wilson M (2013). Indirect effects of the family check-up on school-age academic achievement through improvements in parenting in early childhood. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 762–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis AA (2014). Stigma and the perpetuation of obesity. Social Science & Medicine, 118, 152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruthers AS, Van Ryzin MJ, & Dishion TJ (2014). Preventing high-risk sexual behavior in early adulthood with family interventions in adolescence: outcomes and developmental processes. Prevention Science, 15(1), S59–S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiapa A, Smith JD, Kim H, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2015). The trajectory of fidelity in a multiyear trial of the Family Check-Up predicts change in child problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 1006–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Corno CM, Graydon MM, Wiprovnick AE, & Knoblach DJ (2017). Motivational interviewing, enhancement, and brief interventions over the last decade: a review of reviews of efficacy and effectiveness. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 862–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman Carpentier F, Mauricio AM, Gonzales NA, Millsap RE, Meza CM, Dumka LE, Germán M, & Genalo MT (2007). Engaging Mexican origin families in a school-based preventive intervention. Journal of Primary Prevention, 28(6), 521–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, & Kavanagh KA (2003). The Family Check-Up with high-risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring. Behavior Therapy, 34(4), 553–571. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, & Wilson M (2008). The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development, 79(5), 1395–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Smith JD, Knutson N, Brauer L, Gill A, & Risso J (2014). Family Check-Up: COACH ratings manual. Version 2. Unpublished coding manual. Available from the Child and Family Center, 6217 University of Oregon, Eugene, OR: 97403. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Stormshak EA (2007). Interventions with children and adolescents intervening in children’s lives: an ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care (pp. 141–61, Chapter x, 319 Pages). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, & Kavanagh K (2011). Everyday parenting: a professional’s guide to building family management skills. Champaign, IL: Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, & Coyne JC (1990). Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 108(1), 50–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J, & DuPre E (2008). Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Bandalos DL (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(3), 430–457. 10.1207/s15328007sem0803_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farnesi B-C, Perez A, Holt NL, Morrison KM, Gokiert R, Legault L, Chanoine J-P, Sharma AM, & Ball GDC (2019). Continued attendance for paediatric weight management: a multicentre, qualitative study of parents’ reasons and facilitators. Clinical Obesity, 0, 0, e12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Van Ryzin M, Stormshak EA, & Dishion TJ (2014). Putting theory to the test: examining family context, caregiver motivation, and conflict in the Family Check-Up model. Development and Psychopathology, 26(2), 305–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. t., & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kimber M, Barac R, & Barwick M (2017). Monitoring fidelity to an evidence-based treatment: practitioner perspectives. Clinical Social Work Journal. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Carlo G, & Basilio C (2011). The socialization of culturally related values and the mental health outcomes of Latino youth. In Cabrera NJ & Villarruel FA (Eds.), Latina and Latino children’s mental health: prevention and treatment (pp. 109–131). Westport, CT: Praeger Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, & Saraceno B (2004). The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82(11), 858–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan BM, & Nease DE Jr. (2013). The state of the evidence for integrated behavioral health in primary care. In Talen MR & Burke A (Eds.), Integrated behavioral health in primary care: evaluating the evidence, identifying the essentials (pp. 65–98, Chapter xxiii, 354 Pages). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, & Amari E (2012). The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction, 107(1), 39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio AM, Gonzales NA, & Sandler IN (2018). Preventive parenting interventions: advancing conceptualizations of participation and enhancing reach. Prevention Science, 19(5), 603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2002). Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2009). Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37(2), 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sovereign RG, & Krege B (1988). Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers: II. The Drinker’s Check-up as a preventive intervention. Behavioural Psychotherapy, 16(4), 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, & Rychtarik R (1992). Motivational enhancement therapy manual. (DHHS Publication No. ADM 92–1894). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JP, Kelley ML, Landry DN, Paasch V, Terlecki MA, Johnston CA, & Foreyt JP (2011). Development and validation of the Family Health Behavior Scale. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 6, 2 Part 2, e480–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, & Muthén LK (2018). Mplus, Version 8.1 Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell ME, Boat T, & Warner KE (Eds.). (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakpour AH, Gellert P, Dombrowski SU, & Fridlund B (2015). Motivational interviewing with parents for obesity: an RCT. Pediatrics, 135(3), e644–ee52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, & DiClemente RJ (1983). Towards an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 51, 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, Peterson JL, & Luedicke J (2011). Parental perceptions of weight terminology that providers use with youth. Pediatrics, 128, e786–ee93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Baskin ML, Rahotep SS, Periasamy S, & Rollnick S (2004). Motivational interviewing in health promotion and behavioral medicine. In Cox WM & Klinger E (Eds.), Handbook of motivational counseling: concepts, approaches, and assessment (pp. 457–76, Chapter xxii, 515 Pages): John Wiley & Sons Ltd, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, McMaster F, Bocian A, Harris D, Zhou Y, Snetselaar L, Schwartz R, Myers E, Gotlieb J, Foster J, Hollinger D, Smith K, Woolford S, Mueller D, & Wasserman RC (2015). Motivational interviewing and dietary counseling for obesity in primary care: an RCT. Pediatrics, 135(4), 649–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Berkel C, Hails KA, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2018c). Predictors of participation in the Family Check-Up program: a randomized trial of yearly services from age 2 to 10 years. Prevention Science, 19, 5 (Special issue on participation in preventive interventions: advancing conceptualization and theoretical models), 652–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Berkel C, Jordan N, Atkins DC, Narayanan SS, Gallo C, Grimm KJ, Dishion TJ, Mauricio AM, Rudo-Stern J, Meachum MK, Winslow E, & Bruening MM (2018b). An individually tailored family-centered intervention for pediatric obesity in primary care: study protocol of a randomized type II hybrid effectiveness–implementation trial (Raising Healthy Children study). Implementation Science, 13(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Berkel C, Rudo-Stern J, Montaño Z, St. George SM, Prado G, Mauricio AM, Chiapa A, Bruening MM, & Dishion TJ (2018a). The Family Check-Up 4 Health (FCU4Health): pplying implementation science frameworks to the process of adapting an evidence-based parenting program for prevention of pediatric obesity and excess weight gain in primary care. Frontiers in Public Health, 6(293), 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Dishion TJ, Brown K, Ramos K, Knoble NB, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2016). An experimental study of procedures to enhance ratings of fidelity to an evidence-based family intervention. Prevention Science, 17(1), 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2013). Indirect effects of fidelity to the Family Check-Up on changes in parenting and early childhood problem behaviors. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 962–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Montaño Z, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2015). Preventing weight gain and obesity: indirect effects of a family-based intervention in early childhood. Prevention Science, 16, 408–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Rudo-Stern J, Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Montag S, Brown K, Ramos K, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2019). Effectiveness and efficiency of observationally assessing fidelity to a family-centered child intervention: a quasi-experimental study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(1), 16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preventive Services Task Force, U. S. (2017). Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 317(23), 2417–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, & Nowicka P (2013). Direct and indirect effects of a family-based intervention in early adolescence on parent–youth relationship quality, late adolescent health, and early adult obesity. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(1), 106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C, & Dishion TJ (2007). Parent consultant log. Child and Family Center, University of Oregon. Eugene, OR. [Google Scholar]