Abstract

Glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) is one of the main bioactive components of licorice, and it is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine due to its hepatoprotective, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory and anti-viral functions. Currently, GA is mainly extracted from the roots of cultivated licorice. However, licorice only contains low amounts of GA, and the amount of licorice that can be planted is limited. GA supplies are therefore limited and cannot meet the demands of growing markets. GA has a complex chemical structure, and its chemical synthesis is difficult, therefore, new strategies to produce large amounts of GA are needed. The development of metabolic engineering and emerging synthetic biology provide the opportunity to produce GA using microbial cell factories. In this review, current advances in the metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for GA biosynthesis and various metabolic engineering strategies that can improve GA production are summarized. Furthermore, the advances and challenges of yeast GA production are also discussed. In summary, GA biosynthesis using metabolically engineered S. cerevisiae serves as one possible strategy for sustainable GA supply and reasonable use of traditional Chinese medical plants.

Keywords: glycyrrhetinic acid, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, metabolic engineering, microbial cell factories, natural product production

Introduction

Licorice refers to the legume plant of Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., Glycyrrhiza flata Bat. or Glycyrrhiza glabra L., and it is widely used in traditional herbal medicine (Asl and Hosseinzadeh, 2008). Glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) is one of the main bioactive components of licorice plants and it has two optical isomers, 18 α-GA and 18 β-GA (Zhang and Ye, 2009; Li et al., 2014). Between the two isomers, the 18 α-GA isomer is present at low levels. The 18 β-GA is found at higher levels, and it is the main bioactive licorice component. 18 β-GA has a remarkably broad spectrum of biological activities, including as an anti-inflammatory agent (Kowalska and Kalinowska-Lis, 2019), an anti-tumor agent (Wang et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2019), an immunomodulatory agent (Ayeka et al., 2016), a hepatoprotective agent (Mahmoud and Dera, 2015), and other functional medical effects (Chen et al., 2013; Ding et al., 2020).

Currently, GA is mainly produced by the hydrolysis of glycyrrhizic acid, which is extracted from the dried root and rhizome of licorice (Mukhopadhyay and Panja, 2008; Wang C. et al., 2019). Wild licorice, however, has been severely damaged and has nearly disappeared due to excessive mining (Shu et al., 2011). Moreover, the quality of artificially cultivated licorice is variable, and the GA content in natural licorice is low. The complex structure of GA makes the chemical synthesis of GA difficult (Wang et al., 2018). The demand for GA has increased and the price of GA is high, so exploring other sustainable sources of GA is of great interest.

Introducing the biosynthetic genes of natural products into microbial chassis cells and the construction of microbial cell factories to obtain high levels of targeted natural products have become one of the most essential ways to produce plant natural products (Pyne et al., 2019). The development of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering makes the microbial biosynthesis of GA possible (Wang C. et al., 2019), and microbial cell factories provide a practical and effective way to solve the problem of sustainable production of medical plant resources (Xu et al., 2020).

Microorganisms can utilize a relatively cheap carbon source to balance cell growth and natural product synthesis (Jeandet et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2020). Normally, microorganisms have known genetic background, and there are many ways to genetically manipulate them, making them suitable for use in large-scale fermentation (Xu et al., 2020). At present, there are a variety of natural products, such as artemisinin (Paddon et al., 2013), protopanaxadiol (Dai et al., 2013), ginsenosides (Yan et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2015), tanshinones (Guo et al., 2016), cocoa butter (Wei et al., 2017a; Bergenholm et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2018), and cannabidiol acid (Luo et al., 2019), that have been successfully synthesized using metabolically engineered Saccharomyces. cerevisiae.

In this review, we summarize the current progress for GA production in S. cerevisiae and provide some future prospects for the field.

Chemical Structure of GA

GA is an oleanane-type triterpenoid, and it is soluble in ethanol, methanol, chloroform, ethyl acetate, pyridine and acetic acid, but is insoluble in water (Wang et al., 2018; Kowalska and Kalinowska-Lis, 2019). The chemical structure of GA is complex, hence its chemical synthesis is difficult (Wang C. et al., 2019). The hydroxy group at position C-3 and the carboxyl group at position C-30 are the main functional groups. Currently, chemical strategies are mainly used for modification of GA (Yang et al., 2020). Introduction of protected or de-protected amino acids have been shown to increase GA activity (Schwarz et al., 2014). By esterification of the C-3 and C-30 positions in GA, different GA groups can be introduced and other derivatives can be formed, and these derivatives have been shown to improve the activities of the GA-derived components (Maitraie et al., 2009; Schwarz and Csuk, 2010; Yang et al., 2020). Nowadays, the cost of chemical synthesis of GA is high, while the yield is low (Wang C. et al., 2019). Additionally, large amounts of wastes are generated during chemical synthesis of GA.

GA Biosynthetic Pathway

The production of a plant natural product in microorganisms requires an understanding of its biosynthetic pathways (Wei et al., 2019). Traditional pathway mining strategies are typically carried out through selection of mutant libraries, which is time-consuming and laborious. With the development of bioinformatics and computational biology, it has been possible to identify all potential biosynthetic pathways of the natural products in one species by establishing a multi-layered omics technology platform (Mochida and Shinozaki, 2011). The platform includes omics data analyses of transcripts, genomes, proteomes, metabolomes, the prediction of gene function, and the verification of key genes in the biosynthetic pathways of natural products (Nett et al., 2020).

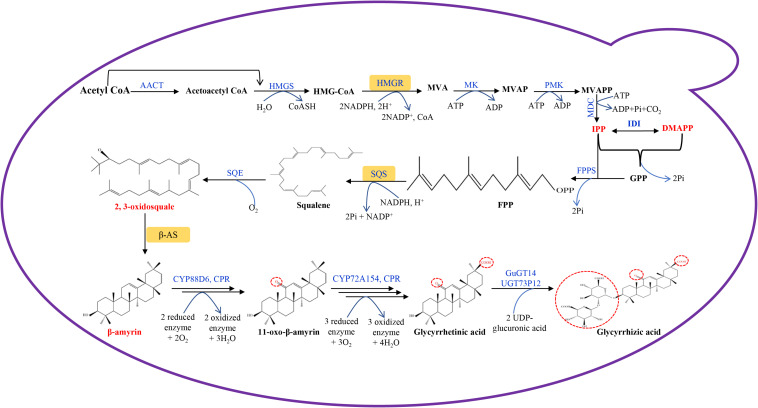

Transcriptomic and genomic sequencing data are available for licorice (Li et al., 2010; Ramilowski et al., 2013; Mochida et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2020), and have contributed to a better understanding of natural product biosynthetic pathways in licorice plants. The GA biosynthetic pathway in licorice plants has been defined (Seki et al., 2011). GA belongs to the oleanane-type triterpenoid group, and shares the same precursor synthetic pathway with other terpenes. Both methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) and mevalonate (MVA) pathways are involved in GA precursor synthesis, but GA is mainly synthesized through the MVA pathway which can be divided into three stages (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Glycyrrhetinic acid biosynthetic pathway designed in engineered S. cerevisiae. AACT, acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase; HMGS, 3-hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl-CoA synthase; HMGR, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase; MK, mevalonate kinase; PMK, phosphomevalonate kinase; MDC, mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase; GPP, geranyl diphosphate; GPPS, geranyl diphosphate synthase; IDI, isopentenyl-pyrophosphate delta isomerase; FPP, farnesyl diphosphate; FPPS, farnesyl diphosphate synthase; SQS, squalene synthase; SQE, squalene epoxidase; β-AS, β-amyrin synthase; CPR, cytochrome P450 reductase; GuGUAT, Glycyrrhiza uralensis UDP-dependent glucuronosyltransferases; MVA, mevalonic acid; MVAP, mevalonate phosphate; MVAPP, mevalonate diphosphate; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate.

In the first stage, acetyl-CoA is catalyzed by acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase (AACT), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase (HMGS), and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR) to generate MVA, followed by multi-step reactions to synthesize isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). HMGR is the first key rate-limiting enzyme in the MVA metabolic pathway, in which HMGR can catalyze the formation of MVA from HMG-CoA, which is an irreversible reaction (Friesen and Rodwell, 2004). IPP and DMAPP have been shown to be the important intermediate products of this process, and they are the precursors for terpenoids synthesis in plant cells (Wang Q. et al., 2019).

Secondly, following the catalysis of geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS), farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS), squalene synthase (SQS) and squalene epoxidase (SQE), IPP is used to synthesize 2,3-oxidosquale. 2,3-oxidosquale is a common precursor for some natural product biosynthesis, such as sterols and triterpenes. SQS synthesize squalene using farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) as substrate, and it has been identified to be a key enzyme which can direct carbon flow to triterpene biosynthesis (Seo et al., 2005).

2,3-oxidosquale is catalyzed by β-amyrin synthease (bAS) to generate β-amyrin, which is an important reaction step in GA biosynthesis. Following this, the licorice enzyme CYP88D6 catalyzes the hydroxylation of the 11-position of β-amyrin, followed by further oxidation to 11-oxo-β-amyrin (Seki et al., 2008). Licorice CYP72A154 further catalyzes a three-step reaction. The C-30 position of 11-oxo-β-amyrin is firstly hydroxylated, then the product has been shown to be oxidized to form an aldehyde, and finally it is again oxidized to form the carboxyl group of GA (Seki et al., 2011). During this process, NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) is the main electron donor to cytochrome P450 (CYP450). The electrons are transferred to CYP450, followed by a redox reaction with the substrate (Zhu et al., 2018). The electron transfer reaction between CPR and CYP450 is the rate-limiting step of the CYP450 redox reaction, which affects GA synthetic efficiency (Zhu et al., 2018). GA is converted to glycyrrhizic acid by the UDP-dependent glucuronosyltransferases of GuGT14 and UGT73P12 (Chen et al., 2019; Nomura et al., 2019).

Metabolic Engineering of S. cerevisiae for GA Production

S. cerevisiae is one of the most commonly used model chassis, in particular grows rapidly on low-cost substrates and genetic manipulation is easy. Besides, the MVA pathway in S. cerevisiae can provide precursors like IPP and DMAPP for terpene synthesis. Many natural products have been successfully synthesized in S. cerevisiae. After a series genetic modification to enhance the MVA pathway in S. cerevisiae, the production of artemisinin can reach 300 mg/L. Further optimization of the metabolic network and fermentation conditions increased the titer to 25 g/L (Paddon et al., 2013). The annual artemisinin output in a 100 m3 fermentation bioreactor is 35 tons, which is equivalent to the output of artemisinin of 50,000 mu in Artemisia annua, showing that yeast cell factories can provide large amounts of natural products in a short time and with limited space.

By introducing more than 20 genes from plants, bacteria or rodents into S. cerevisiae, an artificial S. cerevisiae cell factory that can convert sugars into opioid alkaloids has been successfully constructed, representing a breakthrough in the biosynthesis and manufacturing of opioid alkaloids (Galanie et al., 2015). Additionally, the complete microbial synthesis of major cannabinoids and their derivatives, including cannabigerol acid (CBGA), tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) and cannabidiol acid (CBDA), in S. cerevisiae cell factories has been achieved (Luo et al., 2019). The synthesis of GA requires the MVA pathway to provides precursor substances. S. cerevisiae can be used as an advantageous chassis cell to supply substrates for GA synthesis, and various metabolic engineering strategies had been used for GA production in S. cerevisiae.

β-amyrin serves as the oleanane-type triterpenoid precursor to various downstream products, and increasing β-amyrin synthesis in S. cerevisiae is essential for GA synthesis. The AaBAS gene cloned from A. annua was introduced into S. cerevisiae, which altered the gene expression level of HMGR and lanosterol synthase gene (ERG7), increasing β-amyrin production in S. cerevisiae by 50% to 6 mg/L (Supplementary Table 1; Kirby et al., 2008). This result shows that triterpenes can be produced in S. cerevisiae, and a heterologous gene from another plant could increase β-amyrin production. Subsequently, Dai et al. (2015) integrated two different bAS genes derived from Glycyrrhiza glabra and Panax ginseng, and another copy of native yeast SQS and SQE genes in yeast. Following incubation in YPD medium with 2% glucose for 7 days, Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis showed that the β-amyrin production yield was 107 mg/L with a yield of 9.3 mg/g dry cell weight (DCW) (Supplementary Table 1; Dai et al., 2015). These studies indicated that overexpression of key genes in the GA biosynthetic pathway could increase precursor production.

A combination of stepwise rational refactoring and directed flux regulation strategies can improve β-amyrin production. Introduction of the bAS gene from Glycyrrhiza glabra and the heterologous squalene monooxygenase genes from Candida albicans into S. cerevisiae, combined with overexpression of isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase (IPI), FPPS and SQS genes, increased squalene production. UPC2 is a global transcription factor regulating sterol synthesis in S. cerevisiae, and modifying the UPC2 binding site directed metabolic flux for β-amyrin biosynthesis. After a series of genetic modifications and suitable ethanol fed-batch fermentation, the final titer of β-amyrin in S. cerevisiae reached 138.80 mg/L (Zhang et al., 2015). This suggested that pathway optimization and flux refactoring can improve natural product synthesis in engineered yeast. Liu et al. introduced an optimal acetyl-CoA pathway and deleted an acetyl-CoA competing pathway in S. cerevisiae, balancing various factors that greatly reduced energy consumption and glucose utilization. The final β-amyrin production was found to be 279.0 ± 13.0 mg/L, which is the highest β-amyrin production ever reported (Supplementary Table 1; Liu et al., 2019). This study suggested that a global analysis between precursor supply and product formation, rather than analysis of one key gene, could efficiently improve natural product biosynthesis in engineered microorganisms. In the GA biosynthesis pathway, β-amyrin is further catalyzed by CYP88D6 and CYP72A154 to synthesize GA (Supplementary Table 1; Seki et al., 2008, 2011).

Seki et al. (2011) also confirmed the key roles played by CYP450 genes in the GA biosynthesis pathway by introducing bAS, CYP88DE, CYP72A154, and CPR into wild-type S. cerevisiae, thus redirecting the metabolic flow to GA synthesis. This eventually led to 11-oxo-β-amyrin production levels of 76 μg/L and GA production amounts of 15 μg/L (Supplementary Table 1; Seki et al., 2011). These results indicated the feasibility of GA synthesis in yeast using synthetic biology. It is possible to improve GA production by enhancing the catalytic step in which CYP72A154 converts 11-oxo-β-amyrin to GA. Zhu et al. further balanced oxidation and reduction systems by introducing two novel CYP450 genes, Uni25647 and CYP72A63, and pairing the new cytochrome P450 reductases GuCPR1 from Glycyrrhiza uralensis. With the optimized oxidation and reduction modules, as well as scale-up fed-batch fermentation, 11-oxo-β-amyrin and GA synthesis reached 108.1 ± 4.6 mg/L and 18.9 ± 2.0 mg/L, respectively (Zhu et al., 2018). These are the highest titers ever reported for GA and 11-oxo-β-amyrin synthesized from S. cerevisiae. This work further showed that redox balance mediated by the CYP450 and CPR genes was important for GA synthesis. Wang et al. directed the upstream carbon flux flow from acetyl-CoA to 2,3-oxidosqualene by introducing a newly discovered gene, cytochrome b5, from Glycyrrhiza uralensis (GuCYB5) and overexpressing 10 known MVA pathway genes (ERG20, ERG9, ERG1, tHMG1, ERG10, ERG8, ERG13, ERG12, ERG19, IDI1) of S. cerevisiae. The shaking flask titer of 11-oxo-β-amyrin and GA increased to 80 and 8.78 mg/L, respectively (Supplementary Table 1; Wang C. et al., 2019).

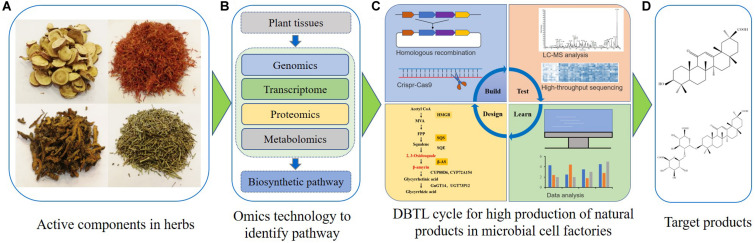

Numerous studies have recently shown the feasibility of GA synthesis in S. cerevisiae (Zhu et al., 2018; Wang C. et al., 2019). According to published results, the microbial synthesis of GA and other natural products might be achieved by several key procedures (Figure 2). First, plants harboring GA or other plant bioactive components are identified. Secondly, transcriptomics, genomics, proteomics and metabolomics analyses are used to recover pathways and key enzymes related to the synthesis of GA or other natural products (Chen et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020; Nett et al., 2020; Srinivasan and Smolke, 2020). After that, appropriate chassis cells which provide precursors for natural product synthesis are selected for construction and optimization of associated microbial cell factories. Some synthetic biology tools, such as CRISPR-Cas9 technology, can efficiently introduce the biosynthetic pathway for GA or other natural products into chassis cells. These chassis cells may then be used as microbial cell factories. The artificially constructed cell factories need to be continuously optimized through the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle (Nielsen and Keasling, 2016). The DBTL cycle includes new enzyme discovery, heterologous gene expression, promoter engineering, metabolic flux balance, pathway optimization, oxidation and reduction system balance, genome-scale metabolic models and other metabolic engineering strategies (Jiang et al., 2020; Ko et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2020; Wang M. et al., 2020). Finally, a high-yield GA or other natural product microbial cell factory can be obtained. As GA is insoluble in water, strategies utilizing the harnessing of lipid metabolism or other sub-organelle metabolism could lead to a high-yield production of GA (Cao et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2019). Besides S. cerevisiae, other yeasts could also be optimized for natural product biosynthesis in the future (Wei et al., 2017b; Wang J. et al., 2020).

FIGURE 2.

Engineering microbial cell factories for synthesis of glycyrrhetinic acid or other plant natural products. (A) The active components are identified in traditional Chinese herbs or other candidate plants. (B) The fresh samples are collected, and multi-omics technologies are used to discover the biosynthetic pathways of natural products. (C) The Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle is used for construction and optimization of microbial cell factories for natural product biosynthesis. (D) Separation and purification of targeted natural products.

Conclusion and Future Prospectives

GA is widely used in clinical practices, but the supply of GA is limited through traditional planting methods. Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology tools provide possible strategies for efficiently producing GA in S. cerevisiae. The successful production of high β-amyrin and GA using engineered S. cerevisiae shows that yeasts are suitable microbial chasses for GA production. The DBTL and other engineering strategies would further increase GA production, possibly providing one sustainable GA supply. In the future, other natural products derived from traditional Chinese herbs or other plants could also be synthesized using engineered S. cerevisiae.

Author Contributions

YW and RG conceived this study. YW, RG, MW, and ZG wrote the manuscript. WL, C-YJ, and X-JJ revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank TopEdit (www.topeditsci.com) for English language editing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31800079) and the Young Talent Promotion Project in Henan Province (2020HYTP038).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2020.588255/full#supplementary-material

References

- Asl M. N., Hosseinzadeh H. (2008). Review of pharmacological effects of Glycyrrhiza sp. and its bioactive compounds. Phytother. Res. 22 709–724. 10.1002/ptr.2362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayeka P. A., Bian Y., Mwitari P. G., Chu X., Zhang Y., Uzayisenga R., et al. (2016). Immunomodulatory and anticancer potential of Gan cao (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.) polysaccharides by CT-26 colon carcinoma cell growth inhibition and cytokine IL-7 upregulation in vitro. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 16:206. 10.1186/s12906-016-1171-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergenholm D., Gossing M., Wei Y. J., Siewers V., Nielsen J. (2018). Modulation of saturation and chain length of fatty acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of cocoa butter-like lipids. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 115 932–942. 10.1002/bit.26518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Yang S., Cao C., Zhou Y. J. (2020). Harnessing sub-organelle metabolism for biosynthesis of isoprenoids in yeast. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 5 179–186. 10.1016/j.synbio.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Hu Z.-M., Song W., Wang Z.-L., He J.-B., Shi X.-M., et al. (2019). Diversity of O-Glycosyltransferases contributes to the biosynthesis of flavonoid and triterpenoid glycosides in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. ACS Synth. Biol. 8 1858–1866. 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Yang S., Zhang L., Zhou Y. J. (2020). Advanced strategies for production of natural products in yeast. iScience 23:100879 10.1016/j.isci.2020.100879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zou L., Li L., Wu T. (2013). The protective effect of glycyrrhetinic acid on carbon tetrachloride-induced chronic liver fibrosis in mice via upregulation of Nrf2. PLoS One 8:e53662. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z., Liu Y., Zhang X., Shi M., Wang B., Wang D., et al. (2013). Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of ginsenosides. Metab. Eng. 20 146–156. 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z., Wang B., Liu Y., Shi M., Wang D., Zhang X., et al. (2015). Producing aglycons of ginsenosides in bakers’ yeast. Sci. Rep. 4 3698–3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H., Deng W., Ding L., Ye X., Yin S., Huang W. (2020). Glycyrrhetinic acid and its derivatives as potential alternative medicine to relieve symptoms in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol. 92 2200–2204. 10.1002/jmv.26064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen J. A., Rodwell V. W. (2004). The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A (HMG-CoA) reductases. Genome Biol. 5 248–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanie S., Thodey K., Trenchard I. J., Filsinger Interrante M., Smolke C. D. (2015). Complete biosynthesis of opioids in yeast. Science 349 1095–1100. 10.1126/science.aac9373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Tian S., Hou J., Zhang Z., Yang L., Hu T., et al. (2020). RNA-Seq based transcriptome analysis reveals the molecular mechanism of triterpenoid biosynthesis in Glycyrrhiza glabra. Bioorg. Med. Chemi. Lett. 30:127102 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Ma X., Cai Y., Ma Y., Zhan Z., Zhou Y. J., et al. (2016). Cytochrome P450 promiscuity leads to a bifurcating biosynthetic pathway for tanshinones. New Phytol. 210 525–534. 10.1111/nph.13790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeandet P., Vasserot Y., Chastang T., Courot E. (2013). Engineering microbial cells for the biosynthesis of natural compounds of pharmaceutical significance. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013:780145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Li C., Teng Y., Zhang R., Yan Y. (2020). Recent advances in improving metabolic robustness of microbial cell factories. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 66 69–77. 10.1016/j.copbio.2020.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby J., Romanini D. W., Paradise E. M., Keasling J. D. (2008). Engineering triterpene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae–β-amyrin synthase from Artemisia annua. he FEBS J. 275 1852–1859. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko Y.-S., Kim J. W., Lee J. A., Han T., Kim G. B., Park J. E., et al. (2020). Tools and strategies of systems metabolic engineering for the development of microbial cell factories for chemical production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 4615–4636. 10.1039/d0cs00155d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska A., Kalinowska-Lis U. (2019). 18beta-Glycyrrhetinic acid: its core biological properties and dermatological applications. Int. J. Cosmet Sci. 41 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Y., Cao H. Y., Liu P., Cheng G. H., Sun M. Y. (2014). Glycyrrhizic acid in the treatment of liver diseases: literature review. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014:872139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Luo H.-M., Sun C., Song J.-Y., Sun Y.-Z., Wu Q., et al. (2010). EST analysis reveals putative genes involved in glycyrrhizin biosynthesis. BMC Genomics 11:268. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Fan J., Wang C., Li C., Zhou X. (2019). Enhanced β-Amyrin synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by coupling an optimal acetyl-CoA supply pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67 3723–3732. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b00653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X., Reiter M. A., Despaux L., Wong J., Denby C. M., Lechner A., et al. (2019). Complete biosynthesis of cannabinoids and their unnatural analogues in yeast. Nature 567 123–126. 10.1038/s41586-019-0978-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T., Shi B., Ye Z., Li X., Liu M., Chen Y., et al. (2019). Lipid engineering combined with systematic metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for high-yield production of lycopene. Metab. Eng. 52 134–142. 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud A. M., Dera H. S. A. (2015). 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid exerts protective effects against cyclophosphamide-induced hepatotoxicity: potential role of PPARγ and Nrf2 upregulation. Genes Nutr. 10:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitraie D., Hung C., Tu H., Liou Y., Wei B., Yang S., et al. (2009). Synthesis, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives as chemical mediators and xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17 2785–2792. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida K., Sakurai T., Seki H., Yoshida T., Takahagi K., Sawai S., et al. (2017). Draft genome assembly and annotation of Glycyrrhiza uralensis, a medicinal legume. Plant J. 89 181–194. 10.1111/tpj.13385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida K., Shinozaki K. (2011). Advances in omics and bioinformatics tools for systems analyses of plant functions. Plant Cell Physiol. 52 2017–2038. 10.1093/pcp/pcr153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay M., Panja P. (2008). A novel process for extraction of natural sweetener from licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) roots. Sep. Purif. Technol. 63 539–545. 10.1016/j.seppur.2008.06.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nett R. S., Lau W., Sattely E. S. (2020). Discovery and engineering of colchicine alkaloid biosynthesis. Nature 584 148–153. 10.1038/s41586-020-2546-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J., Keasling J. D. (2016). Engineering cellular metabolism. Cell 164 1185–1197. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura Y., Seki H., Suzuki T., Ohyama K., Mizutani M., Kaku T., et al. (2019). Functional specialization of UDP-glycosyltransferase 73P12 in licorice to produce a sweet triterpenoid saponin, glycyrrhizin. Plant J. 99 1127–1143. 10.1111/tpj.14409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddon C. J., Westfall P. J., Pitera D. J., Benjamin K. R., Fisher K., Mcphee D. J., et al. (2013). High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature 496 528–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne M. E., Narcross L., Martin V. J. J. (2019). Engineering plant secondary metabolism in microbial systems. Plant Physiol. 179 844–861. 10.1104/pp.18.01291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramilowski J. A., Sawai S., Seki H., Mochida K., Yoshida T., Sakurai T., et al. (2013). Glycyrrhiza uralensis transcriptome landscape and study of phytochemicals. Plant Cell Physiol. 54 697–710. 10.1093/pcp/pct057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S., Csuk R. (2010). Synthesis and antitumour activity of glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18 7458–7474. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S., Lucas S. D., Sommerwerk S., Csuk R. (2014). Amino derivatives of glycyrrhetinic acid as potential inhibitors of cholinesterases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 22 3370–3378. 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki H., Ohyama K., Sawai S., Mizutani M., Ohnishi T., Sudo H., et al. (2008). Licorice β-amyrin 11-oxidase, a cytochrome P450 with a key role in the biosynthesis of the triterpene sweetener glycyrrhizin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 14204–14209. 10.1073/pnas.0803876105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki H., Sawai S., Ohyama K., Mizutani M., Ohnishi T., Sudo H., et al. (2011). Triterpene functional genomics in licorice for identification of CYP72A154 involved in the biosynthesis of glycyrrhizin. Plant Cell 23 4112–4123. 10.1105/tpc.110.082685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J., Jeong J., Shin C., Lo S., Han S., Yu K., et al. (2005). Overexpression of squalene synthase in Eleutherococcus senticosus increases phytosterol and triterpene accumulation. Phytochemistry 66 869–877. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu S., Chen Y., Kang X. (2011). “The plight of China’s wild licorice resources, causes and countermeasures,” in International Conference on Remote Sensing, (environment) and Transportation Engineering, Nanjing, 2715–2718. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan P., Smolke C. D. (2020). Biosynthesis of medicinal tropane alkaloids in yeast. Nature 585 614–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Wu Y., Deng J., Chen N., Zheng Z., Wei Y., et al. (2020). Promoter architecture and promoter engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metabolites 10:320. 10.3390/metabo10080320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Cai H., Zhao H., Yan Y., Shi J., Chen S., et al. (2018). Distribution patterns for metabolites in medicinal parts of wild and cultivated licorice. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 161 464–473. 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Su X., Sun M., Zhang M., Wu J., Xing J., et al. (2019). Efficient production of glycyrrhetinic acid in metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae via an integrated strategy. Microb. Cell Fact. 18:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Quan S., Xiao H. (2019). Towards efficient terpenoid biosynthesis: manipulating IPP and DMAPP supply. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 6:6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Ledesma-Amaro R., Wei Y., Ji B., Ji X.-J. (2020). Metabolic engineering for increased lipid accumulation in Yarrowia lipolytica – A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 313:123707. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Wei Y., Ji B., Nielsen J. (2020). Advances in Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for cocoa butter equivalent production. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8:594081 10.3389/fbioe.2020.594081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Wei Y., Fan Y., Liu Q., Wei W., Yang C., et al. (2015). Production of bioactive ginsenosides Rh2 and Rg3 by metabolically engineered yeasts. Metab. Eng. 29 97–105. 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Shen Y., Qiu R., Chen Z., Chen Z., Chen W. (2017). 18 β-glycyrrhetinic acid exhibits potent antitumor effects against colorectal cancer via inhibition of cell proliferation and migration. Int. J. Oncol. 51 615–624. 10.3892/ijo.2017.4059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Wang P., Wei Y., Liu Q., Yang C., Zhao G., et al. (2015). Characterization of Panax ginseng UDP-glycosyltransferases catalyzing protopanaxatriol and biosyntheses of bioactive ginsenosides F1 and Rh1 in metabolically engineered yeasts. Mol. Plant 8 1412–1424. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Bergenholm D., Gossing M., Siewers V., Nielsen J. (2018). Expression of cocoa genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae improves cocoa butter production. Microb. Cell Factor. 17:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Gossing M., Bergenholm D., Siewers V., Nielsen J. (2017a). Increasing cocoa butter-like lipid production of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by expression of selected cocoa genes. AMB Express 7:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Siewers V., Nielsen J. (2017b). Cocoa butter-like lipid production ability of non-oleaginous and oleaginous yeasts under nitrogen-limited culture conditions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101 3577–3585. 10.1007/s00253-017-8126-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Ji B., Siewers V., Xu D., Halkier B. A., Nielsen J. (2019). Identification of genes involved in shea butter biosynthesis from Vitellaria paradoxa fruits through transcriptomics and functional heterologous expression. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103 3727–3736. 10.1007/s00253-019-09720-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Liu Y., Du G., Ledesma-Amaro R., Liu L. (2020). Microbial chassis development for natural product biosynthesis. Trends Biotechnol. 38 779–796. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Fan Y., Wei W., Wang P., Liu Q., Wei Y., et al. (2014). Production of bioactive ginsenoside compound K in metabolically engineered yeast. Cell Res. 24 770–773. 10.1038/cr.2014.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhu Q., Zhong Y., Cui X., Jiang Z., Wu P., et al. (2020). Synthesis, anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory activities of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives. Bioorg. Chem. 101:103985. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Cao Q., Liu J., Liu B., Li J., Li C. (2015). Refactoring β-amyrin synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. AIChE J. 61 3172–3179. 10.1002/aic.14950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Ye M. (2009). Chemical analysis of the Chinese herbal medicine Gan-Cao (licorice). J. Chromatogr. A 1216 1954–1969. 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.07.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Wu G., Cai D., Xu B., Yan M., Ma T., et al. (2019). Synthesis and biological activity of glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives as antitumor agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 178 623–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M., Wang C., Sun W., Zhou A., Wang Y., Zhang G., et al. (2018). Boosting 11-oxo-β-amyrin and glycyrrhetinic acid synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via pairing novel oxidation and reduction system from legume plants. Metab. Eng. 45 43–50. 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.