Abstract

Background&Aims:

Frailty, as measured by the liver frailty index (LFI), is associated with liver transplant (LT) waitlist mortality. We sought to identify an optimal LFI cutoff that predicts waitlist mortality.

Approach&Results:

Adults with cirrhosis awaiting LT without hepatocellular carcinoma at 9 LT centers in the United States with LFI assessments were included. Multivariable competing risk analysis assessed the relationship between LFI and waitlist mortality. We identified a single LFI cutoff by evaluating the fit of the competing risk models, searching for the cutoff that gave the best model fit (as judged by the pseudo-log-likelihood). We ascertained the area under the curve (AUC) in an analysis of waitlist mortality to find optimal cutoffs at 3, 6, or 12 months. We used the AUC to compare the discriminative ability of LFI+Model for End Stage Liver Disease-sodium (MELDNa) versus MELDNa alone in 3-month waitlist mortality prediction. Of 1,405 patients, 37(3%), 82(6%), and 135(10%) experienced waitlist mortality at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. LFI was predictive of waitlist mortality across a broad LFI range: 3.7-5.2. We identified an optimal LFI cutoff of 4.4 (95%CI:4.0-4.8) for 3-month, 4.2 (95%CI:4.1-4.4) for 6-month, and 4.2 (95%CI:4.1-4.4) for 12-month mortality. The AUC for prediction of 3-month mortality for MELDNa was 0.73; the addition of LFI to MELDNa improved the AUC to 0.79.

Conclusions:

LFI is predictive of waitlist mortality across a wide spectrum of LFI values. The optimal LFI cutoff for waitlist mortality was 4.4 at 3 months and 4.2 at 6 and 12 months. The discriminative performance of LFI+MELDNa was greater than MELDNa alone. Our data suggest that incorporating LFI with MELDNa can more accurately represent waitlist mortality in LT candidates.

Keywords: frailty, liver transplantation, liver frailty index, waitlist mortality, cutoff

INTRODUCTION

Frailty has emerged as a significant driver of morbidity and mortality in patients with cirrhosis.1–7 We developed and validated the Liver Frailty Index to objectively quantify the construct of frailty in patients with cirrhosis.8 The Liver Frailty Index utilizes individual components (i.e. grip strength, chair stands, balance testing) of several instruments that have been well-established in the field of geriatrics. A major advantage of the Liver Frailty Index is that it can be easily integrated into clinical practice, has excellent interrater reliability and reproducibility, and can be assessed longitudinally.1,2,9,10 Furthermore, the Liver Frailty Index has come to represent another metric of illness severity in cirrhosis that is otherwise not captured by more traditional mortality risk prediction calculators, such as the Model for End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, that rely solely on hepatic function.

We have previously demonstrated that the Liver Frailty Index is strongly associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation.8,11–14 Furthermore, the Liver Frailty Index can capture the mortality associated with portal hypertensive complications, including ascites and encephalopathy, which can often be difficult to objectively quantify in clinical practice.11 What has been lacking, however, is a specific threshold for the Liver Frailty Index above which patients with cirrhosis experience significantly higher risk for mortality, which is useful specifically for developing algorithms for clinical practice. When we originally developed the Liver Frailty Index, we designated the cutoff at the 80th percentile (>4.5) of our derivation cohort of >500 patients to define “frail”, paralleling the methodology that was used for the most commonly-used frailty metric, the Fried Frailty Phenotype.15 While this cutoff does indeed stratify patients at higher risk of death, it is yet unknown as to whether this represents the statistically optimal cutoff for the Liver Frailty Index to define the greatest risk.

As the Liver Frailty Index becomes more broadly implemented into clinical practice,16,17 it is increasingly important to identify clinically relevant cutoffs that can be used by clinicians for decision-making. Leveraging our large, national multicenter cohort of nine hepatology centers, we aimed to (1) identify an Liver Frailty Index threshold to predict significantly greater risk for waitlist mortality in patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation and (2) determine if the addition of Liver Frailty Index to MELD-sodium (MELDNa) improved waitlist mortality prognostication above and beyond MELDNa alone.

METHODS

Study Population

We analyzed data from the Multi-Center Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation Study (FrAILT), a prospective, longitudinal cohort study that involves 9 liver transplant centers in the United States. Adult participants 18 years or older with cirrhosis who were evaluated in the outpatient liver transplant setting at the following institutions were eligible: University of California, San Francisco (n=895), Baylor University Medical Center (n=89), Columbia University Medical Center (n=88), Duke University (n=48), Johns Hopkins University (n=157), University of Pittsburgh (n=42), Loma Linda University (n=35), Northwestern University (n=27), and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (n=24). Patients were excluded if they carried a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma or were listed with MELDNa exception points because their waitlist mortality was not dependent on their native liver function. We also excluded patients who did not speak English or Spanish because the consent forms were only available in these languages. Once enrolled, patients’ outcomes were obtained prospectively. The institutional review board from each site approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to enrollment in the study.

Frailty Assessment

We assessed frailty using the Liver Frailty Index. Briefly, the Liver Frailty Index consists of 3 performance-based tests:

Grip strength: the average of 3 trials, measured in the patient’s dominant hand using a hand dynamometer;

Timed chair stands: measured as the number of seconds it takes to do 5 chair stands with the patient’s arms folded across the chest;

Balance testing: measured as the number of seconds that the patient can balance in 3 positions (feet placed side to side, semitandem, and tandem) for a maximum of 10 seconds each.

These 3 tests were administered by trained study personnel. The Liver Frailty Index incorporates these 3 individual components of frailty using the calculator available at: http://liverfrailtyindex.ucsf.edu.

Additional Data Collection

Demographic data were extracted from the clinic visit note from the same day as the Liver Frailty Index assessment. Patients were considered to have a diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease if it was reported in their electronic health record. Laboratory data, including the MELDNa, was collected within 3 months of the Liver Frailty Index assessment date. The most recent collection date and time that had a complete set of labs closest to the baseline visit was used. Based on the hepatologist’s recorded physical examination or written management plan occurring on the same day as the frailty assessment, ascites was categorized as absent if ascites was not present on the physical exam or present if ascites was present on exam and/or the patient was noted to be undergoing large-volume paracenteses. Hepatic encephalopathy was determined at the baseline study visit from the time to complete the Numbers Connection Test A18 performed at the time of frailty assessment. Hepatic encephalopathy was categorized as present if participants took 45 seconds or more to complete the task. This cutoff was selected based on normative data determined from healthy participants and compared with individuals with and without hepatic encephalopathy.18

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographics were presented as medians (interquartile ranges [IQR]) for continuous variables or percentages for categorical variables. The primary outcome was waitlist mortality, defined as the combined outcome of death or delisting for being too sick for liver transplantation. A locally weighted scatterplot smoothing method was used to visually estimate the association between Liver Frailty Index and waitlist mortality; restricted cubic splines were then performed to assess for linearity in the relationship between Liver Frailty Index and waitlist mortality.

Next, we identified a single Liver Frailty Index cutoff by two approaches. First, multivariable competing risk regression was used to assess the association between frailty and waitlist mortality. Deceased donor liver transplantation was treated as the competing risk. Patients who underwent living donor liver transplantation were censored on the day of their liver transplantation. Patients removed for reasons other than being too sick (e.g. relapse of substance abuse, nonadherence, or inadequate social support) were also censored on the day of their removal from the waitlist. We evaluated the fit of the competing risk models, searching for the Liver Frailty Index cutoff that gave the best model fit as judged by the pseudo-log-likelihood. Second, we used the area under the curve (AUC) in an analysis of waitlist mortality by 3, 6, and 12 months to find the optimal cutoff using the Liu method.19

To evaluate the impact of the Liver Frailty Index on improving mortality prediction of MELDNa, we compared the discriminative ability of Liver Frailty Index+MELDNa versus MELDNa alone using the AUC,20,21 and the additive value of Liver Frailty Index to MELDNa alone using the method of DeLong et al22 at 3, 6, and 12 months. We also compared the proportion of patients whose risk of waitlist mortality was correctly reclassified using MELDNa versus Liver Frailty Index+MELDNa using the net reclassification index. The net reclassification index used the risk of waitlist mortality stratified by risk categories based on the cohort event rate and clinical relevance at 3 months (<3%, 3-6%, and ≥6%), 6 months (<6%, 6-10%, ≥10%), and 12 months (<10%, 10-15%, ≥15%). Finally, to assess the comparative effects of MELDNa and Liver Frailty Index on waitlist mortality, we plotted the cumulative incidence of waitlist mortality using a combination of MELDNa and Liver Frailty Index scores at their 20th and 80th percentiles.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics of the Entire Cohort

A total of 1,405 patients with cirrhosis were included. Baseline characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1. To summarize, median (IQR) age was 57 years (49-63), 41% were female, 87% were non-Hispanic white, and median body mass index was 28 kg/m2. The primary etiology of cirrhosis was chronic hepatitis C in 25%, alcoholic liver disease in 27%, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in 19%. Less common etiologies included autoimmune or cholestatic liver disease (15%) and other causes (e.g. cryptogenic cirrhosis, polycystic liver and kidney disease, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease). Rates of hypertension were 39% and those of diabetes were 30%. The median (IQR) MELDNa score was 18 (14-22) and albumin was 3.1 g/dL (2.7-3.6). By the end of follow up, 232 (17%) had the primary outcome of death or delisting for being too sick for liver transplantation, 444 (32%) underwent deceased donor liver transplantation, and 475 (34%) were still waiting. The number (%) of patients who experienced waitlist mortality was 37 (3%) at 3-months, 82 (6%) at 6-months, and 135 (10%) at 12-months. Median follow-up time was 245 days (IQR 100-498).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1,405 Patients with Cirrhosis Included in This Study

| All (n=1,405) N (%) or Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 57 (49-63) |

| Women | 587 (41%) |

| Race-ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,226 (87%) |

| Black | 78 (6%) |

| Hispanic | 7 (0.5%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 76 (5%) |

| Native American | 10 (0.7%) |

| Other | 8 (0.6%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28 (25-33) |

| Etiology of liver disease | |

| Chronic hepatitis C virus | 355 (25%) |

| Alcohol | 383 (27%) |

| Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | 264 (19%) |

| Autoimmune or cholestatic | 210 (15%) |

| Chronic hepatitis B virus | 27 (2%) |

| Other | 166 (12%) |

| Hypertension | 544 (39%) |

| Diabetes | 422 (30%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 88 (6%) |

| MELDNa score | 18 (14-22) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.5 (1.5-4.1) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 (0.8-1.6) |

| INR | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 137 (134-139) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.1 (2.7-3.6) |

| Dialysis | 66 (5%) |

| Ascites (present) | 529 (38%) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (numbers connection test >45) | 582 (42%) |

| Outcome | |

| Waiting | 475 (34%) |

| Death or delisted for being too sick for transplantation | 232 (17%) |

| Deceased donor liver transplantation | 444 (32%) |

| Other | 254 (18%) |

| Liver frailty index | 4.0 (3.5-4.5) |

IQR = Interquartile range; MELDNa = Model for End Stage Liver Disease-sodium

Identifying an Optimal Liver Frailty Index Cutoff

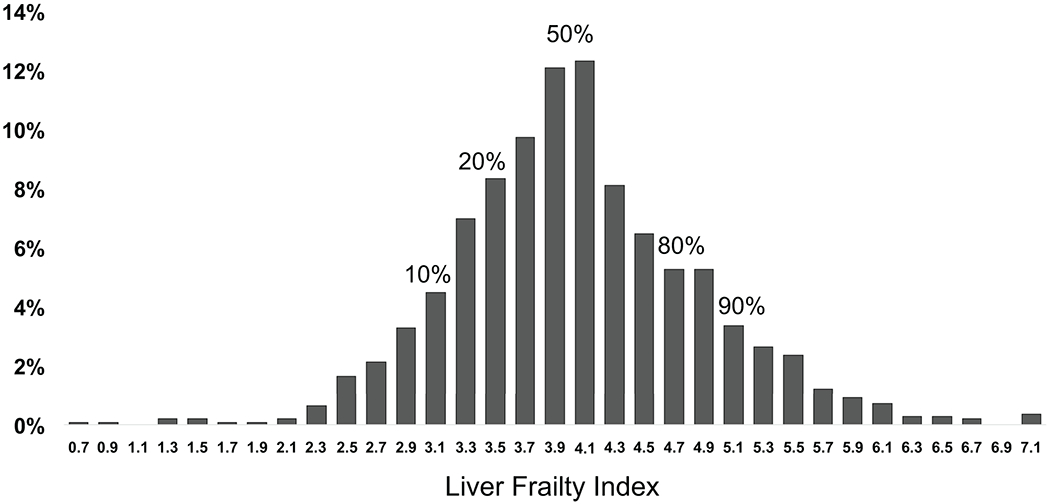

Figure 1 shows the distribution of Liver Frailty Index scores for the cohort. Median Liver Frailty Index was 4.0 (IQR 3.5-4.5).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Liver Frailty Index scores for 1,405 outpatients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation. Higher values indicate a higher degree of frailty.

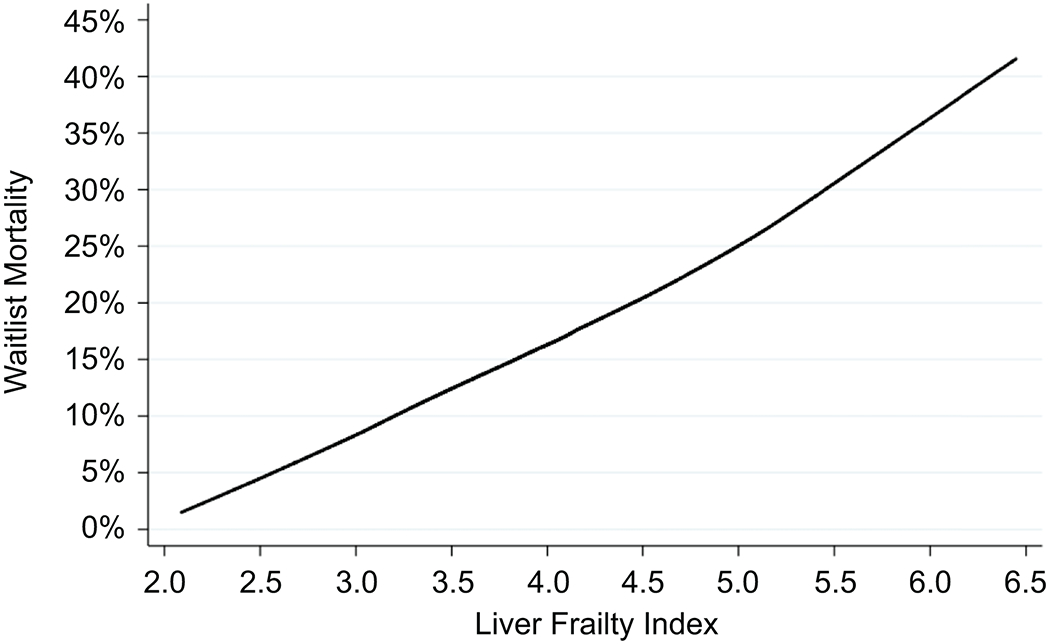

Using a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing curve, we found a monotonic relationship between the Liver Frailty Index and waitlist mortality (Figure 2). To confirm that the association between the Liver Frailty Index and waitlist mortality was truly monotonic, we fit a model using restricted cubic splines. We found no statistically significant difference between the flexible, spline fit and a linear fit (p=0.283), supporting linearity.

Figure 2.

Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing curve showing the association between the Liver Frailty Index and waitlist mortality

Using the best model fit of our competing risk analysis (as judged by the log pseudo-likelihood), we found that the cutoff that gave the best model fit ranged between Liver Frailty Index values of 3.7 and 5.2. In other words, the Liver Frailty Index was predictive of waitlist mortality across this range of values, and those with higher Liver Frailty Index values at each cut-point between 3.7 and 5.2 experienced higher waitlist mortality. Using the AUC approach to more precisely identify a cutoff that could be used in clinical practice, we identified an optimal (highest AUC) Liver Frailty Index cutoff of 4.4 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.0-4.8; c-statistic=0.72) for 3-month, 4.2 (95% CI: 4.1-4.4; c=0.66) for 6-month, and 4.2 (95% CI: 4.1-4.4; c-statistic=0.62) for 12-month mortality.

Discriminative Ability of MELDNa and Liver Frailty Index Compared to MELDNa Alone

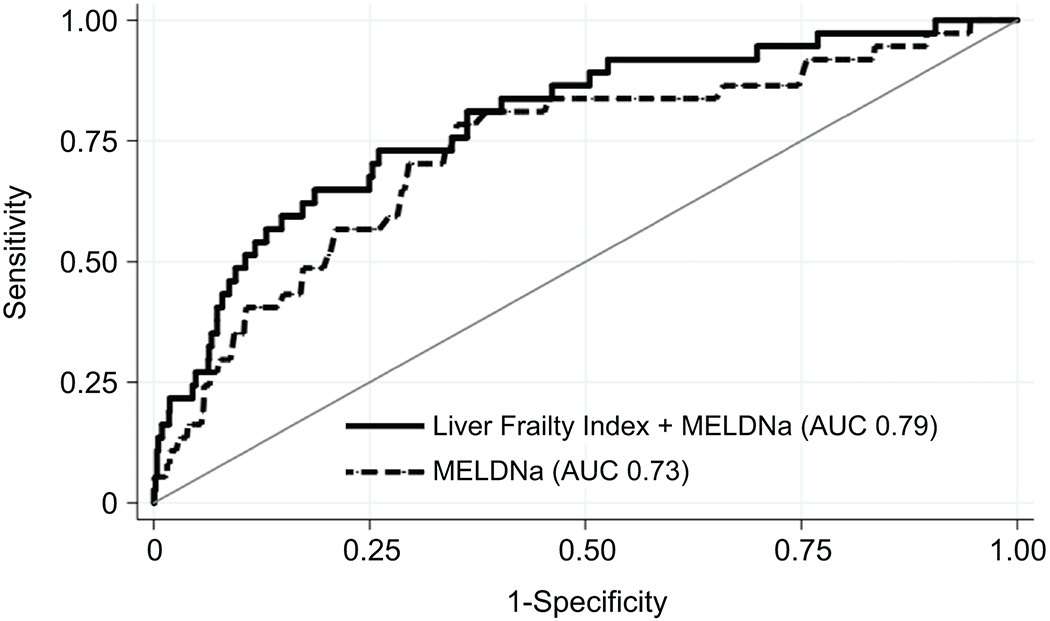

We then evaluated the ability of the Liver Frailty Index to enhance 3-, 6-, and 12-month mortality risk predictions over MELDNa alone. The ability of MELDNa to correctly rank patients according to their 3-month mortality (c-statistic) was 0.73 (95% CI: 0.64-0.82). The combination of MELDNa and Liver Frailty Index had better discrimination for predicting 3-month mortality with a c-statistic of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.72-0.87) (Figure 3). Compared with MELDNa alone, the Liver Frailty Index+MELDNa correctly reclassified 14% of deaths/delistings and 3% of non-deaths/non-delistings for a total net reclassification index of 17%. In the prediction of 6-month mortality, the combination of MELDNa and Liver Frailty Index (c-statistic 0.73, 95% CI: 0.68-0.79) had superior discrimination compared to MELDNa alone (c-statistic 0.69, 95% CI: 0.64-0.75) with a net reclassification index of 14%. Finally, in the prediction of 12-month mortality, the combination of MELDNa and Liver Frailty Index (c-statistic 0.69, 95% CI: 0.65-0.74) had superior discrimination compared to MELDNa alone (c-statistic 0.65, 95% CI: 0.60-0.70) with a net reclassification index of 12%.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the Liver Frailty Index + MELDNa versus MELDNa alone in 3-month waitlist mortality prediction

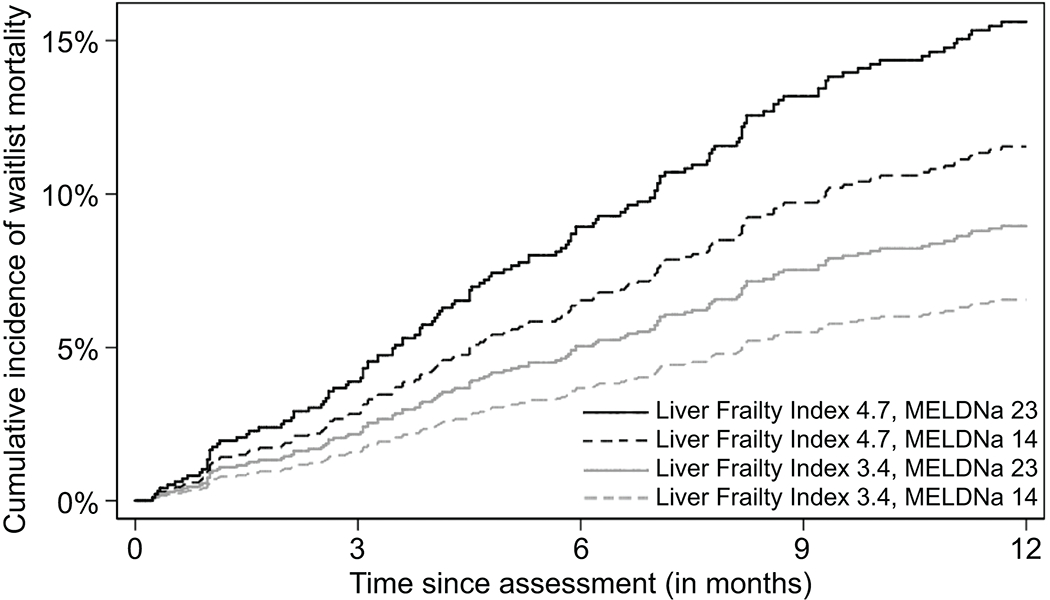

To better understand the comparative effects of MELDNa and Liver Frailty Index on waitlist mortality, we also assessed the cumulative incidence of waitlist mortality for four hypothetical patients using a combination of MELDNa and Liver Frailty Index scores at their 20th and 80th percentiles (Figure 4). For example, consider two patients who are listed for liver transplantation with the same MELDNa score of 14, one with a Liver Frailty Index of 4.7 (80th percentile) and the other with a Liver Frailty Index of 3.4 (20th percentile). They both have relatively low, but equal, priority on the waitlist based on their MELDNa scores. However, the patient with a Liver Frailty Index of 4.7 has a 91% greater risk of waitlist mortality than his/her counterpart with a Liver Frailty Index of 3.4 (Figure 4; black dashed line versus grey dashed line). This greater risk of waitlist mortality at a Liver Frailty Index of 4.7 (versus 3.4) persists at higher MELDNa scores as well (black solid line versus grey solid line).

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of waitlist mortality for four patients with cirrhosis on the liver transplant waitlist classified by a combination of MELDNa and Liver Frailty Index scores. Liver Frailty Index scores (3.4 and 4.7) and MELDNa scores (14 and 23) were selected because they represented the bottom 20%ile and top 80%ile values for the cohort.

DISCUSSION

The general construct of frailty has long been used in clinical practice to facilitate decision-making for patients with cirrhosis, including whether they are suitable candidates for liver transplantation. Previously, there was no objective tool for the frailty assessment, and clinicians have relied solely on the “eyeball test” for this determination. We developed the Liver Frailty Index to standardize, objectify, and quantify this construct for patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation.8 We have previously demonstrated that the Liver Frailty Index conceptually enhances mortality risk prediction over the “eyeball test” alone.14 We have also shown that the Liver Frailty Index has excellent interrater reliability among different individuals administering the test with an intraclass coefficient of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.91–0.95).9 Since its inception, it has increasingly been adopted in clinical practice and has been integrated into the American Society of Transplantation’s Frailty Toolkit in Liver Transplantation.17 In this study, we aimed to identify optimal cutoffs of the Liver Frailty Index to define “frail” that could facilitate clinical decision-making. Leveraging our 9-center prospective cohort of 1405 patients, we found that a Liver Frailty Index >4.4 identifies “frail” patients at higher risk of 3-month waitlist mortality, and a Liver Frailty Index >4.2 identifies those with greater 6-month and 12-month waitlist mortality. The addition of the Liver Frailty Index to MELDNa results in improvement in the prognostic value of MELDNa at 3 months, increasing the AUC from 0.73 to 0.79 and improving waitlist mortality classification by 17%. Importantly, the Liver Frailty Index also enhances risk prediction over MELDNa alone at 6 and 12 months, demonstrating its utility in predicting mortality at longer follow-up times on the waitlist.

Notably, we also demonstrated that the association between Liver Frailty Index and waitlist mortality was linear. The Liver Frailty Index was associated with waitlist mortality across a broad range of Liver Frailty Index values from 3.7 to 5.2. This is particularly clinically relevant given that the median Liver Frailty Index for our cohort was 4.0. In other words, at every Liver Frailty Index value within this range, those with higher Liver Frailty Index values experienced higher risk of waitlist mortality. Furthermore, when we combined the Liver Frailty Index with the MELDNa score, we found that higher Liver Frailty Index scores portended a greater risk of waitlist mortality in patients with low (20th percentile) and high (80th percentile) MELDNa scores. These findings suggest that the Liver Frailty Index is useful across the full spectrum of MELDNa values, and can further aid in risk stratifying patients listed for liver transplantation who in theory have similar waitlist mortality based solely on their MELDNa scores (Figure 4).

How can these Liver Frailty Index cutoffs be used in our day-to-day clinical practice? We propose that the Liver Frailty Index should be measured in all patients with cirrhosis who present to their outpatient gastroenterology or hepatology clinic visits. As recommended by the American Society of Transplantation Expert Opinion Statement on Frailty in Liver Transplantation,17 severity of frailty should guide intensity of recommendations for nutritional and exercise interventions. Now, incorporating the cutoffs identified in this study, we recommend that patients with Liver Frailty Index scores of >4.2 be encouraged to engage in intensive prehabilitation—maybe even inpatient rehabilitation if available—and be re-assessed every 2–4 weeks for response to intervention. If otherwise suitable for liver transplantation, providers should also urge these patients to more actively seek living donor and appropriate extended criteria donor options or evaluation at centers with a lower transplant MELDNa score to accelerate their path to transplant. Ultimately, the ability to accurately identify a high-risk “frail” subgroup will allow clinicians to prioritize prehabilitation efforts and expedited access to transplantation for those who require them the most.

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. First, we enrolled only outpatients in this study with a median MELDNa score of 18, which is commensurate with the median MELDNa score at listing of patients in the U.S. Therefore, we do not know the utility of the Liver Frailty Index at very high MELDNa scores nor in hospitalized patients. However, the utility of the Liver Frailty Index might be greatest in the outpatient setting, where patients may have a window of opportunity and time to engage in prehabilitation or seek more expedited access to transplantation through living donors or multiple listings. Second, we analyzed the Liver Frailty Index measurement that was ascertained at the time of enrollment into the FrAILT study, which could have occurred at any time while the patient was on the waitlist (not necessarily at listing). This reflects our belief that the Liver Frailty Index is prognostic at any time during a patient’s waitlisting and can be used as a dynamic marker of waitlist mortality, similar to the same way we use the MELDNa score at any time point on the waitlist. Additionally, we assessed only patients who are awaiting liver transplantation and received care at highly specialized, tertiary-care liver transplant centers; as such, our data may not be generalizable to the general population of patients with cirrhosis. Finally, we could not account for the heterogeneity of practice patterns between the 9 different transplant centers, which spanned 7 United Network for Organ Sharing regions. However, the varying center-specific practice patterns, waiting times, access to organs, and diversity of our multicenter cohort reflects “real world” data that is more generalizable to all patients listed for liver transplant across the United States.

In conclusion, we offer specific cutoffs to define the “frail” phenotype in patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation. These cutoffs can guide clinicians in identifying those at highest risk of waitlist mortality to facilitate decision-making and focus resources on this subset of high-risk patients. Our data also demonstrate the applicability of the Liver Frailty Index at a wide range of values and its ability to enhance waitlist mortality prediction over MELDNa alone, lending support to the broad implementation of the Liver Frailty Index into clinical hepatology practice.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was funded by NIH K23AG048337 (Lai), NIH R01AG059183 (Lai, McCulloch), NIH P30DK026743 (Lai, Dodge), NIH K24DK101828 (Segev), AASLD Advanced/Transplant Hepatology Award (Kardashian), and NIH 5T32DK060414–17 (Ge). These funding agencies played no role in the analysis of the data or the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- AUC

area under the curve

- CI

confidence interval

- FrAILT

Functional Assessment in Liver Transplant Study

- IQR

interquartile range

- LT

liver transplant

- MELDNa

Model for End Stage Liver Disease-sodium

REFERENCES

- 1.Lai JC, Feng S, Terrault NA, Lizaola B, Hayssen H, Covinsky K. Frailty predicts waitlist mortality in liver transplant candidates. Am. J. Transplant 2014;14:1870–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai JC, Dodge JL, Sen S, Covinsky K, & Feng S. Functional decline in patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation: Results from the functional assessment in liver transplantation (FrAILT) study. Hepatology 2016; 63:574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tandon P, Reddy KR, O’Leary JG, Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Wong F, et al. A Karnofsky performance status-based score predicts death after hospital discharge in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2017;65:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tandon P, Tangri N, Thomas L, Zenith N, Shaikh T, Carbonneau M, et al. A Rapid Bedside Screen to Predict Unplanned Hospitalization and Death in Outpatients With Cirrhosis: A Prospective Evaluation of the Clinical Frailty Scale. Am. J. Gastroenterol 2016;111:1759–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carey EJ, Steidley DE, Aqel BA, Byrne TJ, Mekeel KL, Rakela J, et al. Six-minute walk distance predicts mortality in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:1373–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinclair M, Poltavskiy E, Dodge JL, & Lai JC. Frailty is independently associated with increased hospitalisation days in patients on the liver transplant waitlist. World J. Gastroenterol 2017;23:899–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn MA, Josbeno DA, Tevar AD, Rachakonda V, Ganesh SR, Schmotzer AR , et al. Frailty as Tested by Gait Speed is an Independent Risk Factor for Cirrhosis Complications that Require Hospitalization. Am. J. Gastroenterol 2016;111:1768–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai JC, Covinsky KE, Dodge JL, Boscardin WJ, Segev DL, Roberts JP, et al. Development of a novel frailty index to predict mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2017;66:564–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang CW, Lesback A, Chau S, Lai JC. The Range and Reproducibility of the Liver Frailty Index. Liver Transpl. 2019;25:841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai JC, Dodge JL, Kappus MR, Dunn MA, Volk ML, Duarte-Rojo A, et al. Changes in frailty are associated with waitlist mortality in patients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatol 2020;doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai JC, Rahimi RS, Verna EC, Kappus MR, Dunn MA, McAdams-DeMarco M, et al. Frailty Associated With Waitlist Mortality Independent of Ascites and Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Multicenter Study. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1675–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haugen CE, McAdams-DeMarco M, Verna EC, Rahimi R, Kappus MR, Dunn MA, et al. Association Between Liver Transplant Wait-list Mortality and Frailty Based on Body Mass Index. JAMA Surg 2019;154(12):1103–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haugen CE, McAdams-DeMarco M, Holscher CM, Ying H, Gurakar AO, Garonzik-Wang J, et al. Multicenter Study of Age, Frailty, and Waitlist Mortality Among Liver Transplant Candidates. Ann. Surg 2019. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai JC, Covinsky KE, McCulloch CE, & Feng S. The Liver Frailty Index Improves Mortality Prediction of the Subjective Clinician Assessment in Patients With Cirrhosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol 2018;113:235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 2001;56:M146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobashigawa J, Dadhania D, Bhorade S, Adey D, Berger J, Bhat G, et al. Report from the American Society of Transplantation on frailty in solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant 2019;19:984–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai JC, Sonneday CJ, Tapper EB, Duarte-Rojo A, Dunn MA, Bernal W, et al. Frailty in liver transplantation: An expert opinion statement from the American Society of Transplantation Liver and Intestinal Community of Practice. Am. J. Transplant 2019;19:1896–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissenborn K, Rückert N, Hecker H, & Manns MP. The number connection tests A and B: interindividual variability and use for the assessment of early hepatic encephalopathy. J. Hepatol 1998;28:646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X Classification accuracy and cutpoint selection. Statistics in Medicine 2012;31:2676–2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.May S & Hosmer DW. A simplified method of calculating an overall goodness-of-fit test for the Cox proportional hazards model. Lifetime Data Anal 1998;4:109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. Wiley, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeLong ER, DeLong DM & Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]