Abstract

Background

Prior studies report that adults with intellectual disability (ID) have cause of death patterns distinct from adults in the general population but do not provide comparative analysis by specific causes of death.

Methods

Data are from the National Vital Statistics System 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files. We utilised adjusted odds ratios to identify causes of death that were more common for adults whose death certificate indicated ID (N = 22 512) than for adults whose death certificate did not indicate ID (N = 32 738 229), controlling for severity level of ID. We then examine the associations between biological sex and race-ethnicity and causes of death solely among adults with ID.

Results

The leading cause of death for adults with and without ID indicated on their death certificate was heart disease. Adults with ID, regardless of the severity of the disability, had substantially higher risk of death from pneumonitis, influenza/pneumonia and choking. Adults with mild/moderate ID also had higher risk of death from diabetes mellitus.Differences in cause of death trends were associated with biological sex and race-ethnicity.

Conclusions

Efforts to reduce premature mortality for adults with ID should attend to risk factors for causes of death typical in the general population such as heart disease and cancer, but also should be cognisant of increased risk of death from choking among all adults with ID, and diabetes among adults with mild/moderate ID. Further research is needed to better understand the factors determining comparatively lower rates of death from neoplasms and demographic differences in causes of death among adults with ID.

Keywords: age, biological sex, cause of death, intellectual disability, mortality, race-ethnicity

Background

Because of the advancements in social and health care services, longevity for people with intellectual disability (ID) has markedly improved since the early 1960s. These improvements resulted in a larger percentage of adults with ID who do not have a comorbid developmental disability (e.g. cerebral palsy) now living into their early 60s (Landes et al. 2019a). Despite this definite progress, adults with ID in the United States who do not have a comorbid developmental disability, on average, still die at ages 10–15 years earlier than adults in the general population (Landes et al. 2019a). This mortality disadvantage is substantially more pronounced than the age at death gap in the United States between men and women (6.4 years), and White and Black Americans (7.3 years) (National Vital Statistics System 2017).

Leading causes of death are distinct for adults with ID and likely influence differences in age at death. The leading causes of death for the US general population in 2016, in rank order, were diseases of the heart, malignant neoplasms, accidents and chronic lower respiratory diseases (Xu et al. 2018). For adults with ID, respiratory disease is frequently reported as the leading cause of death, followed closely by, or superseded by, heart disease, then followed in varying order by neoplasms, external causes of death and diseases of the nervous system (Glover et al. 2017; Heslop et al. 2014; Janicki et al. 1999; Lauer et al. 2015; OLeary et al. 2018; Oppewal et al. 2018; Trollor et al. 2017).

While there has been recent attention to cause of death patterns among the population of adults with ID in the United Kingdom (Heslop et al. 2014; Heslop and Glover 2015; Hosking et al. 2016) and Netherlands (Oppewal et al. 2018), the last study addressing this topic among the US population was based on 1984–1993 administrative data for adults with ID receiving services in New York State (Janicki et al. 1999). Beyond datedness, because of the challenges presented by the data available (O’Leary et al. 2018), there are concerns with this literature, including (1) reliance on broad ICD-10 chapter codes as opposed to particular causes of death, (2) limited analysis of cause of death trends by severity of ID, (3) lack of differentiation between individuals who do/do not have a comorbid developmental disability and (4) limited to no attention to possible biological sex and/or racial-ethnic differences in cause of death trends that are observed in the general population (Heron 2018).

We address these limitations by providing updated analysis on mortality trends among US adults with ID. Our focus is on adults with ID who do not have a comorbid developmental disability, such as Down syndrome or cerebral palsy, as this population lives comparatively longer lives than their peers with a comorbid developmental disability (Landes et al. 2019a). To increase the specificity of comparative analysis, we utilised a standardised list of the leading causes of death in the general population supplemented with causes that are more prevalent among adults with ID and analyse causes of death by ID severity classification, overall and across age groups. In order to better understand whether demographic characteristics are determinant of differential trends in cause of death, we then explore whether biological sex and race-ethnicity are associated with differences in cause of death trends among adults with ID. Compared with adults without an ID, we hypothesise that there will be increased risk of death for adults with ID from respiratory disease and lower risk of death from neoplasms. We also hypothesise that cause of death trends among adults with ID will vary by severity level, biological sex and race-ethnicity in ways that can meaningfully inform efforts to reduce premature mortality for this population.

Methods

Data for this study are from the National Vital Statistics System 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause of Death Mortality files. A note on what we can discern about whose disability is/is not reported on their death certificate data is in order at this point. Estimates of the adult, age 18 and over, population with ID in the United States range from 0.30% to 0.52% (LaPlante and Carlson 1996; Larson et al. 2001). These estimates include adults with Down syndrome. To our knowledge, a refined estimate of adults with ID without Down syndrome does not exist. In the 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause of Death Mortality data, 0.15% of all adults (49 604 out of 32 760 741), age 18 and over, who died during this time period had an ID and/or Down syndrome identified on their death certificate. Thus, if prior estimates are correct, the death certificates utilised in this study report ID for 29–50% of the population of adults with an ID who died between 2005 and 2017.

This leads to the question of whose ID is/is not reported on their death certificate. Our assumption is that the majority of adults who died with Down syndrome, as well as those with more severe types of ID, were more likely to have their disability recognised at the time of their death and reported on their death certificate, as these types of disability are frequently considered apropos to the causal death mechanism. However, there may be times that even when recognised, the disability is not reported on the death certificate as the individual certifying the death certificate either does not consider the disability apropos to the causal death mechanism or is not clear on how to report the disability on the death certificate (Landes et al. 2020b).

In general, the likelihood of having the disability not reported on the death certificate is greater for adults with milder forms of ID whose disability may not be recognised at the time of death, or, even when recognised, may not be considered relevant to the causal pathway leading to death. However, there may be instances when those with milder severity have their ID reported, such as when the medical practitioner certifying the death certificate either had extensive knowledge of their medical history, adequate access to prior records that included the disability diagnosis or interaction with a family member or caregiver who revealed the disability diagnosis. Thus, it is our contention that death certificate data likely include a more representative sample of adults with more severe types of ID that were clearly recognisable at the time of death and adults for whom the certifier had awareness of their ID, even if not visibly recognisable at the time of death. This means that comparisons of cause of death trends between adults with and without ID will be biased toward the null because some individuals with ID will be categorised as being part of the general population.

Prior research reveals substantial heterogeneity in age at death patterns between adults with and without various types of intellectual and developmental disabilities, with adults with ID, on average, living longer than their peers with other types of developmental disability such as cerebral palsy or Down syndrome, or peers with comorbid developmental disabilities, such as ID and cerebral palsy (Landes et al. 2019a). Thus, we focus in this paper on the 22 512 adults, aged 18 and over at the time of death, with an ID (ICD-10 codes F70–79) indicated on their death certificate who did not have a comorbid developmental disability (cerebral palsy, Down syndrome and other rare developmental disabilities) also indicated, and the 32 738 229 adults without an ID indicated on their death certificate. We provide cause of death analysis for adults with Down syndrome (Landes et al. 2020a) and cerebral palsy (in progress) in other studies.

Prior to analysis, we revised the underlying cause of death for the 23.9% of death certificates that had an ID erroneously reported as their underlying cause of death utilising a sequential revision process that is fully detailed in a prior study (Landes et al. 2019b). ID severity level is based upon classification provided via10 codes on the death certificate: no identified ID (no ICD-10 code for ID), mild/moderate ID (ICD-10 codes F70–71), severe/profound ID (F72–73) and unspecified ID (F78–79). Age at death was coded in single years and ranged from 18 to 126. As 87% of adults with ID died by age 80, when graphing predicted probabilities, the top-end age category included those age 80 and over. Biological sex was dichotomously coded female and male. Race-ethnicity included the categories Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Other. Year of death indicated the calendar year of death and was coded in single years.

We initially analysed rates of death for 22 causes of death. These included the 15 leading causes of death in the United States during 2016 as reported by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (Xu et al. 2018), as well as seven causes of death that are more prevalent among adults with ID: (1) choking – aspiration, ingestion or inhalation of gastric contents, food or other objects; (2) respiratory failure, not elsewhere classified; (3) intestinal obstruction and Gastro Oesophageal Reflux Disease; (4) seizure disorders; (5) protein/calorie malnutrition and volume depletion; (6) dementia and (7) unknown/unspecified (Prasher and Janicki 2019; Rubin and Crocker 2006). Unknown was indicated when decedents had only ID listed on their death certificate with no other ICD-10 codes included on the death certificate. Unspecified indicated that the underlying cause of death was an R-code, indicative of symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified. Based upon this initial analysis, we identified and focus this study on the top 10 causes of death for adults with ID, plus the category for unknown/unspecified causes of death. A list of the 11 causes of death and corresponding ICD-10 codes used in this study is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptives for all study variables by intellectual disability status, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files (N = 32 760 741)

| Variable | No intellectual disability (N = 32 738 229) | All intellectual disability (N = 22 512) | Mild/Moderate intellectual disability (N = 621) | Severe/Profound intellectual disability (N = 3765) | Unspecified intellectual disability (N = 18 126) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age – M (SD) | 73.95 (0.00) | 61.10 (0.11) | 63.62 (0.67) | 57.17 (0.26) | 61.83 (0.12) |

| Female | 49.94% | 45.44% | 46.05% | 45.47% | 45.41% |

| Race-ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 79.91% | 80.55% | 83.74% | 80.53% | 80.45% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.47% | 12.68% | 9.50% | 12.70% | 12.79% |

| Hispanic | 5.88% | 5.10% | 4.67% | 5.23% | 5.09% |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 2.74% | 1.67% | 2.09% | 1.54% | 1.68% |

| Year – M (SD) | 2011.18 (0.00) | 2010.42 (0.02) | 2010.55 (0.14) | 2010.39 (0.06) | 2010.42 (0.03) |

| Cause of death | |||||

| Heart diseases (ICD-10 codes: 100–109, 111,113 and 120–151) | 24.61% | 15.61% | 18.36% | 14.45% | 15.76% |

| Pneumonitis due to solids and liquids (ICD-10 code: J69) | 0.72% | 8.86% | 4.35% | 13.12% | 8.13% |

| Influenza and pneumonia (ICD-10 codes: J09-J18) | 2.18% | 8.71% | 3.06% | 9.85% | 8.66% |

| Malignant neoplasms (ICD-10 codes: C00-C97) | 22.92% | 7.12% | 11.11% | 4.89% | 7.45% |

| Dementia/Alzheimer’s (ICD-10 codes: F03 and G30) | 7.37% | 5.07% | 5.96% | 2.12% | 5.65% |

| Choking – aspiration, ingestion or inhalation of gastric contents, food or other objects (ICD-10 codes: W78-W80) | 0.18% | 4.68% | 3.86% | 5.44% | 4.55% |

| Cerebrovascular diseases (CVA) (ICD-10 codes: 160–169) | 5.36% | 3.24% | 3.54% | 1.70% | 3.55% |

| Genitourinary diseases – nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis; urinary tract infection (ICD-10 codes: N00–N07, NI7–N19, N25–27 and N39) | 2.37% | 3.16% | 2.25% | 2.84% | 3.25% |

| Diabetes mellitus (ICD-10 codes: E10–E14) | 2.96% | 3.07% | 7.41% | 1.49% | 3.25% |

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases (CLRD) (ICD-10 codes: J40–J47) | 5.65% | 3.04% | 4.67% | 2.34% | 3.13% |

| Unknown/unspecified (No UCOD, R-codes) | 1.30% | 4.63% | 2.90% | 6.27% | 4.35% |

Percentages unless otherwise specified.

After providing a comparison of all study variables by disability status, we then estimated the risk of dying from each specific cause of death between adults with and without ID utilising adjusted odds ratios (AORs) from logistic regression models. AORs are similar to standardised mortality odds ratios (Miettinen and Wang 1981; Smith and Kliewer 1995; Yang et al. 2002) as they compute the risk of dying from a specific cause of death as opposed to dying from all other causes of death. This analytic strategy is useful for groups, such as adults with ID, for whom we do not have a population estimate that is required as the denominator to calculate standardised mortality rates. All odds ratios are adjusted for age and year of death. For ease of interpretation, we use language of comparative risk when describing AORs. We then compare predicted probabilities of dying from each cause of death for adults with and without ID across age. Because of a limited number of cases, analysis of causes of death across age was only conducted for the top 3 causes of death for adults with mild/moderate ID. All analyses comparing adults with and without ID are stratified by ID severity level. After completing the comparative analysis, we utilise odds ratios to assess whether there were biological sex and racial-ethnic differences in causes of death among adults with ID. We utilised the STATA 16.0 (College Station, TX) for all analysis.

Results

A comparison of all study variables by ID severity level is provided in Table 1. Among adults with an ID reported on their death certificate, 80.5% were identified as having an unspecified level of ID, 2.8% had mild/moderate ID and 16.7% had severe/profound ID. The difference in age at death between adults with and without ID was 12.8 years, but varied by ID severity: mild/moderate – 10.3 years, severe/profound – 16.8 years and unspecified – 12.1 years. Differences in the biological sex and race-ethnic distribution between groups were not remarkable. For all other measures in the study other than cerebrovascular disease and genitourinary diseases, those identified as having unspecified ID fell between the averages for those specified as having mild/moderate and severe/profound ID.

The leading cause of death for all groups, with or without ID, was heart disease. While the second and third leading causes of death for adults without ID were malignant neoplasms and dementia/Alzheimer’s, this was not the case for adults with ID. For adults with mild/moderate ID, the second and third leading causes of death were malignant neoplasm and diabetes mellitus. For adults with severe/profound or unspecified ID, the second and third leading causes were respiratory causes of death, pneumonitis and influenza/pneumonia.

There were some apparent similarities in the unadjusted cause of death rates between adults with and without ID that extended across all severity levels of ID. Compared with adults without ID, all adults with ID had higher rates of death from pneumonitis, influenza and pneumonia, choking, genitourinary disease and unknown/unspecified causes of death and lower rates of death from heart disease, malignant neoplasms, dementia/Alzheimer’s, cerebrovascular disease and chronic lower respiratory diseases. While the higher rates of death from pneumonitis, influenza and pneumonia, and choking were present for all adults with ID, they were more pronounced for those with severe/profound or unspecified ID. Revealing further differences in causes of death by disability classification, rates of death from malignant neoplasms among adults with mild/moderate ID, although still lower than those without an ID, were higher than their peers with severe/profound or unspecified ID. Rates of death from dementia/Alzheimer’s were lowest in adults with severe/profound ID, and adults with unspecified ID had the highest rates of death from genitourinary diseases. Also of note, dissimilar from adults with severe/profound or unspecified ID, adults with mild/moderate ID were more likely than those without ID to die from diabetes mellitus.

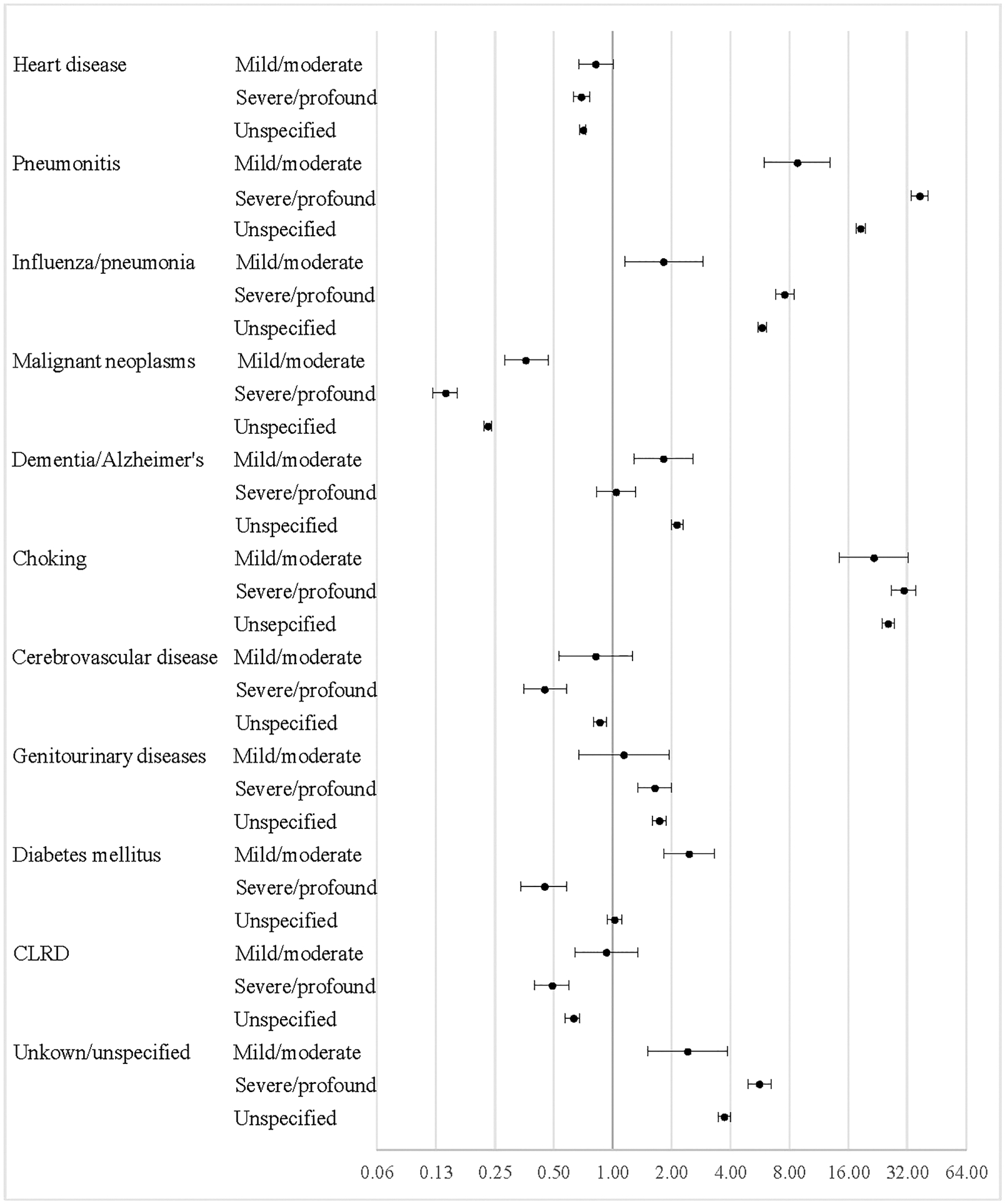

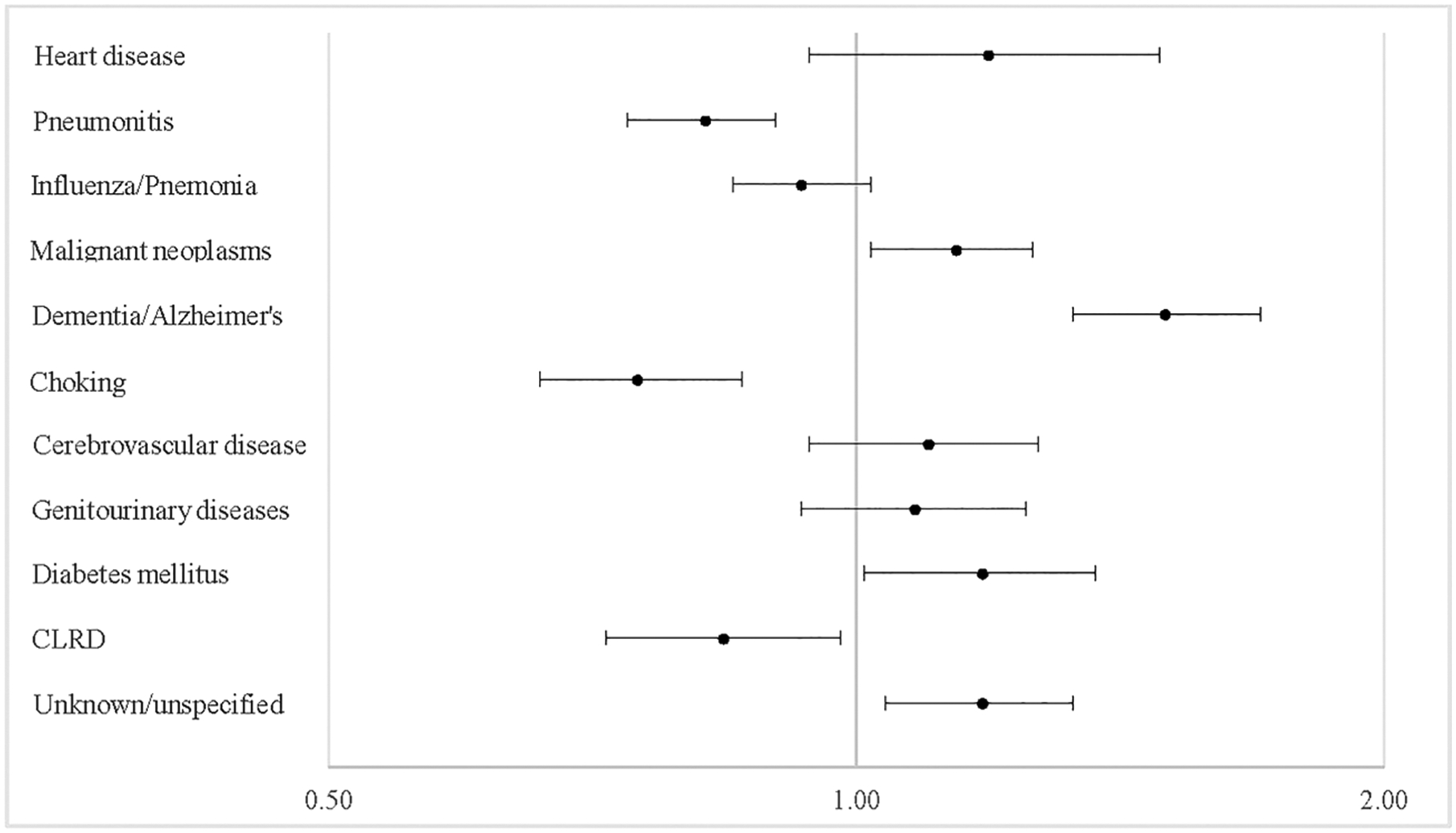

In most instances, these bivariate comparisons were replicated in multivariate analysis. AOR for all causes of death are visually depicted in Fig. 1 and fully reported in Appendix S1. We focus our attention on the most pronounced differences. Compared with adults without ID, adults with ID were 20.8 times more likely [95% confidence interval (CI) = 19.8, 21.8] to die from pneumonitis, with the degree of this disparity ranging from 8.8 times more likely (95% CI = 6.0, 12.9) for adults with mild/moderate ID, to 37 times more likely (95% CI = 33.7, 40.8) for adults with severe/profound ID. Similar patterns were present for influenza and pneumonia, choking and unknown/unspecified causes. Adults with ID were 5.9 times more likely (95% CI = 5.6, 6.2) overall to die from influenza and pneumonia, ranging from 1.8 times more likely (95% CI = 1.2, 2.9) for those with mild/moderate ID to 7.6 times more likely (95% CI = 6.8, 8.4) for those with severe/profound ID; 26.3 times more likely (95% CI = 24.7, 28.0) overall to die from choking, ranging from 21.6 times more likely (95% CI = 14.4, 32.5) for those with mild/moderate ID to 30.7 times more likely (95% CI = 26.7, 35.4) for those with severe/profound ID; and 4 times more likely (95% CI = 3.7, 4.2) overall to die from unknown/unspecified causes, ranging from 2.4 times more likely (95% CI = 1.5, 3.9) for those with mild/moderate ID to 5.6 times more likely (95% CI = 4.9, 6.4) for those with severe/profound ID. Confirming bivariate comparisons, adults with mild/moderate ID were 2.5 times more likely (95% CI = 1.8, 3.3) to die from diabetes than adults without ID. This disparity was not present among their peers with other severity levels of ID. Increased risk of death from dementia/Alzheimer’s was only present for adults with mild/moderate or unspecified ID and for genitourinary diseases only among adults with severe/profound or unspecified ID.

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratios for specific causes of death between adults with and without intellectual disability by level of disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality file (N = 32 760 741).

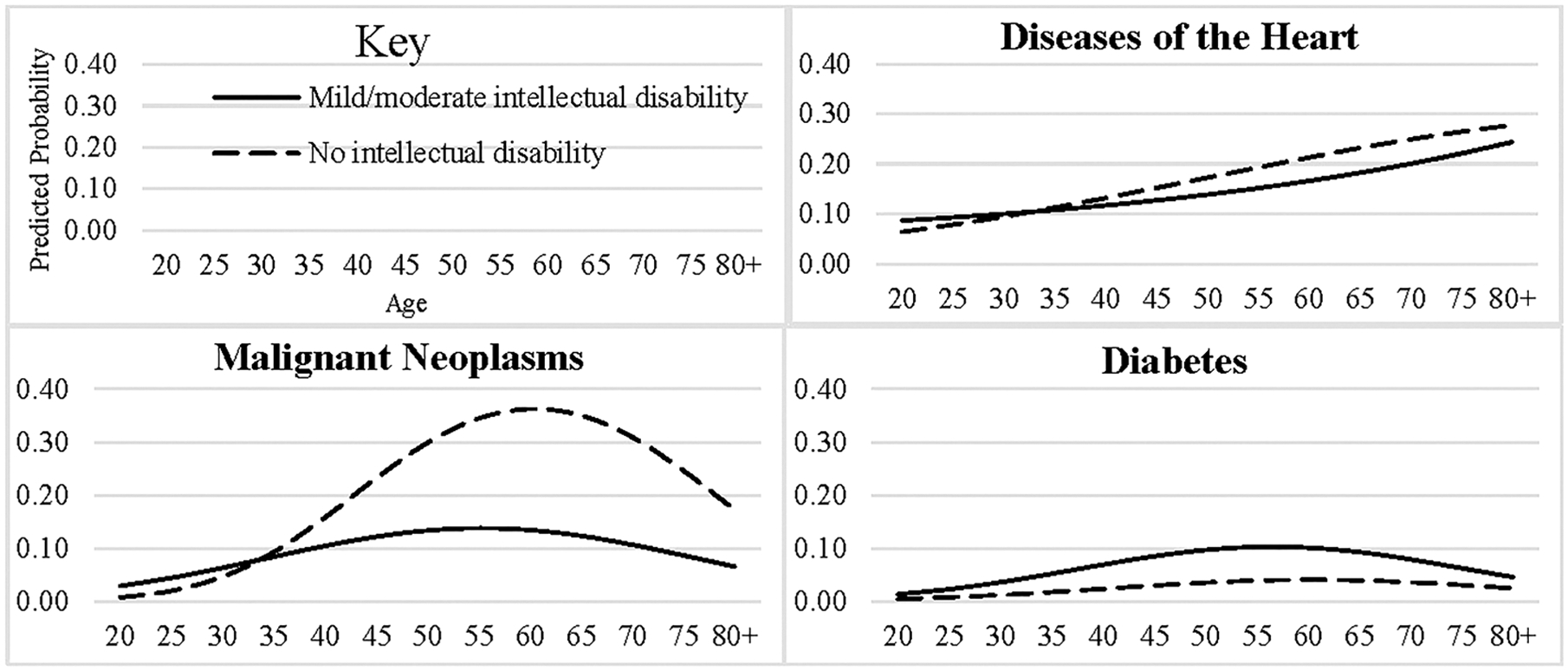

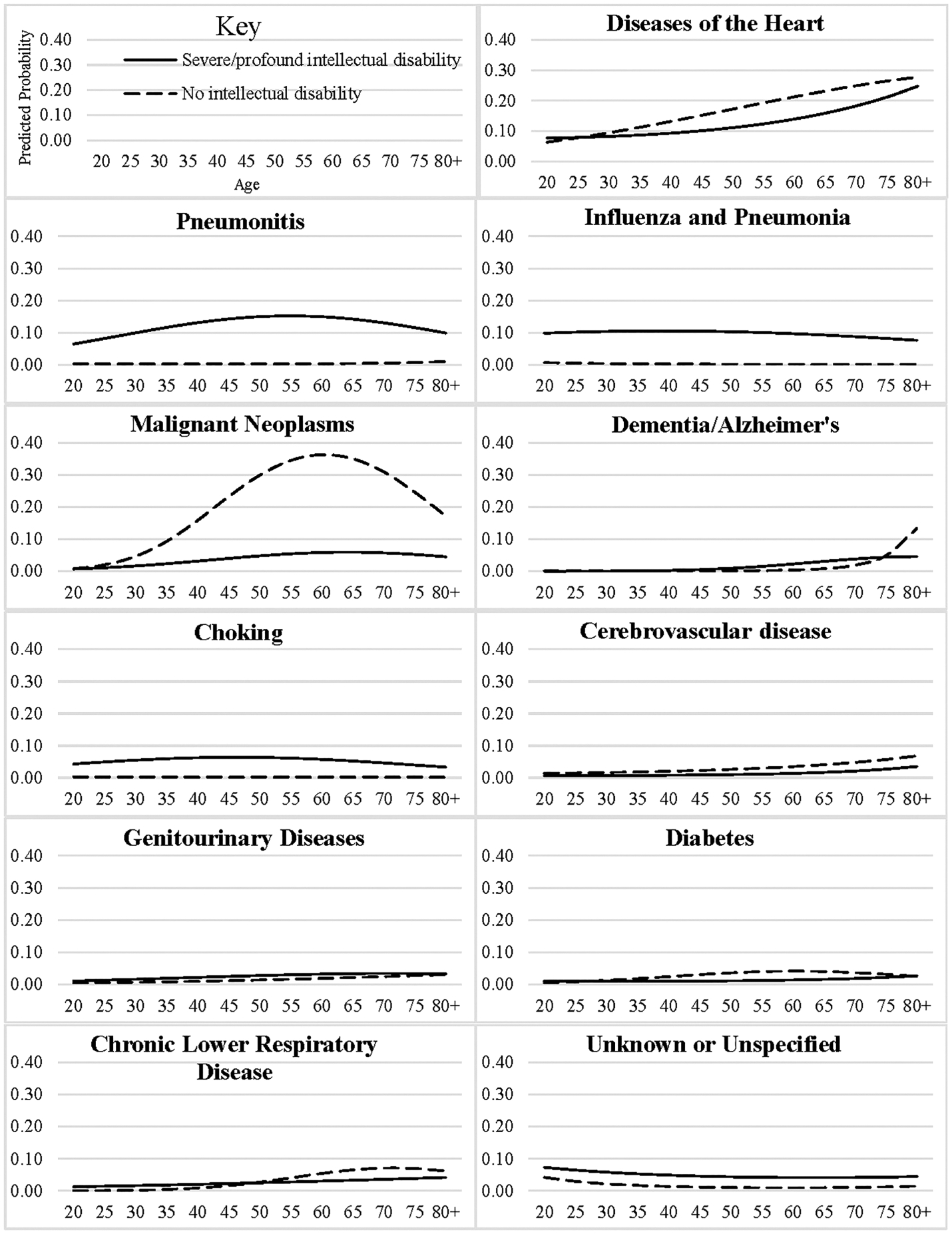

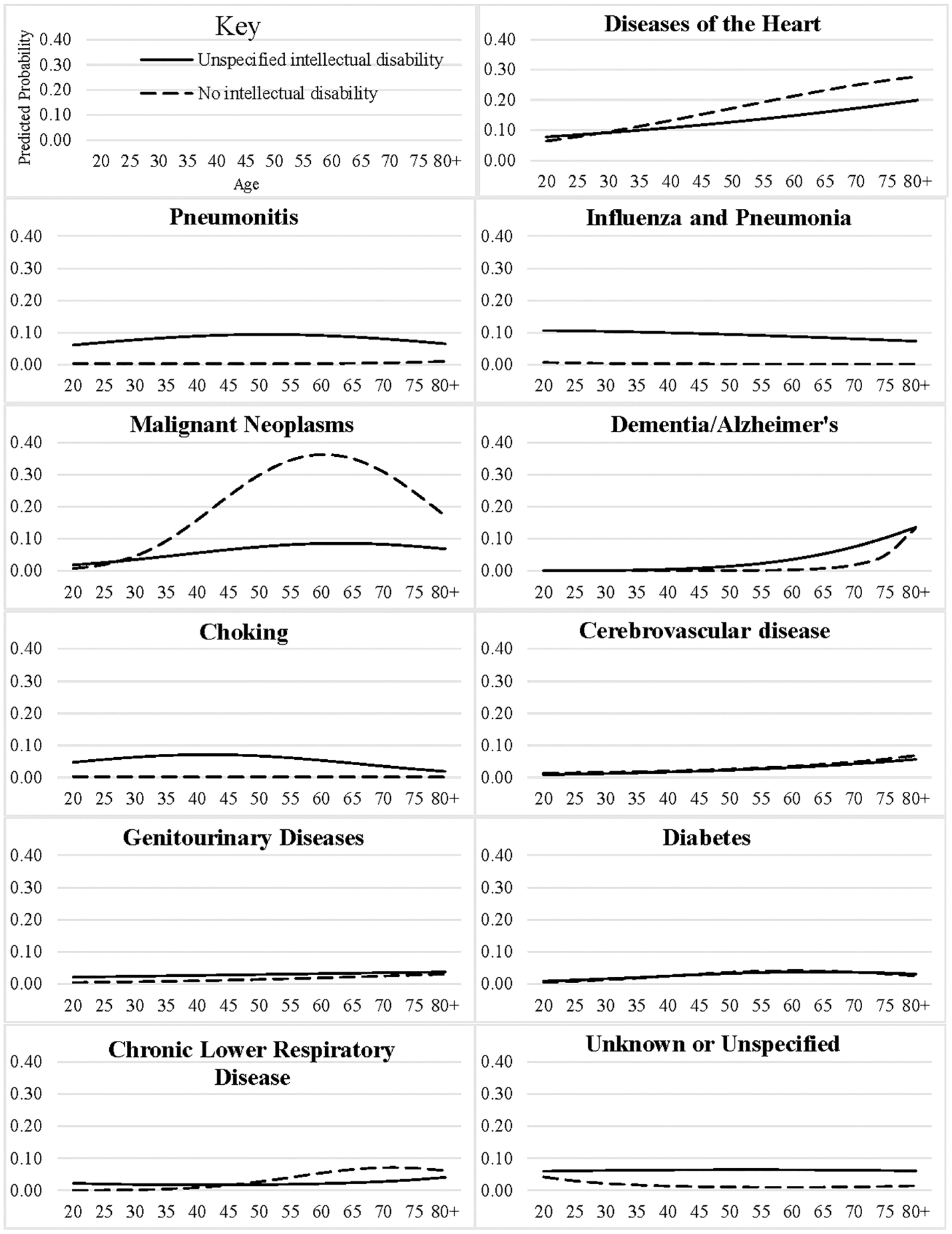

These disparities in cause of death between adults with and without ID often persisted across the life course. Predicted probabilities for the top 3 causes of death for adults with and without mild/moderate ID are presented visually in Fig. 2, and for all causes of death for adults with severe/profound or unspecified ID in Figs 3–4. Full models for these graphs are provided in Appendix S2. For adults with mild/moderate ID, increased risk of death from diabetes extended across the life course. Although still lower than for those without ID, rates of death from malignant neoplasms were higher for those with mild/moderate than those with severe/profound or unspecified ID. For adults with severe/profound and unspecified ID, increased risk of death from pneumonitis, influenza and pneumonia, choking and unknown/unspecified causes extended across all ages. For adults with unspecified ID, increased risk of death from dementia/Alzheimer’s disease was present from the ages of 50 to 80, likely indicating an earlier age of onset from this disease, and higher probability of death from genitourinary diseases persisted across all ages.

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities of top 3 causes of death by age for adults with and without mild/moderate intellectual disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause of Death Mortality files (N = 32 738 850).

Figure 3.

Predicted probabilities of specific causes of death by age for adults with and without severe/profound intellectual disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause of Death Mortality file (N = 32 741 994).

Figure 4.

Predicted probabilities of specific causes of death by age for adults with and without unspecified intellectual disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause of Death Mortality file (N = 32 778 867).

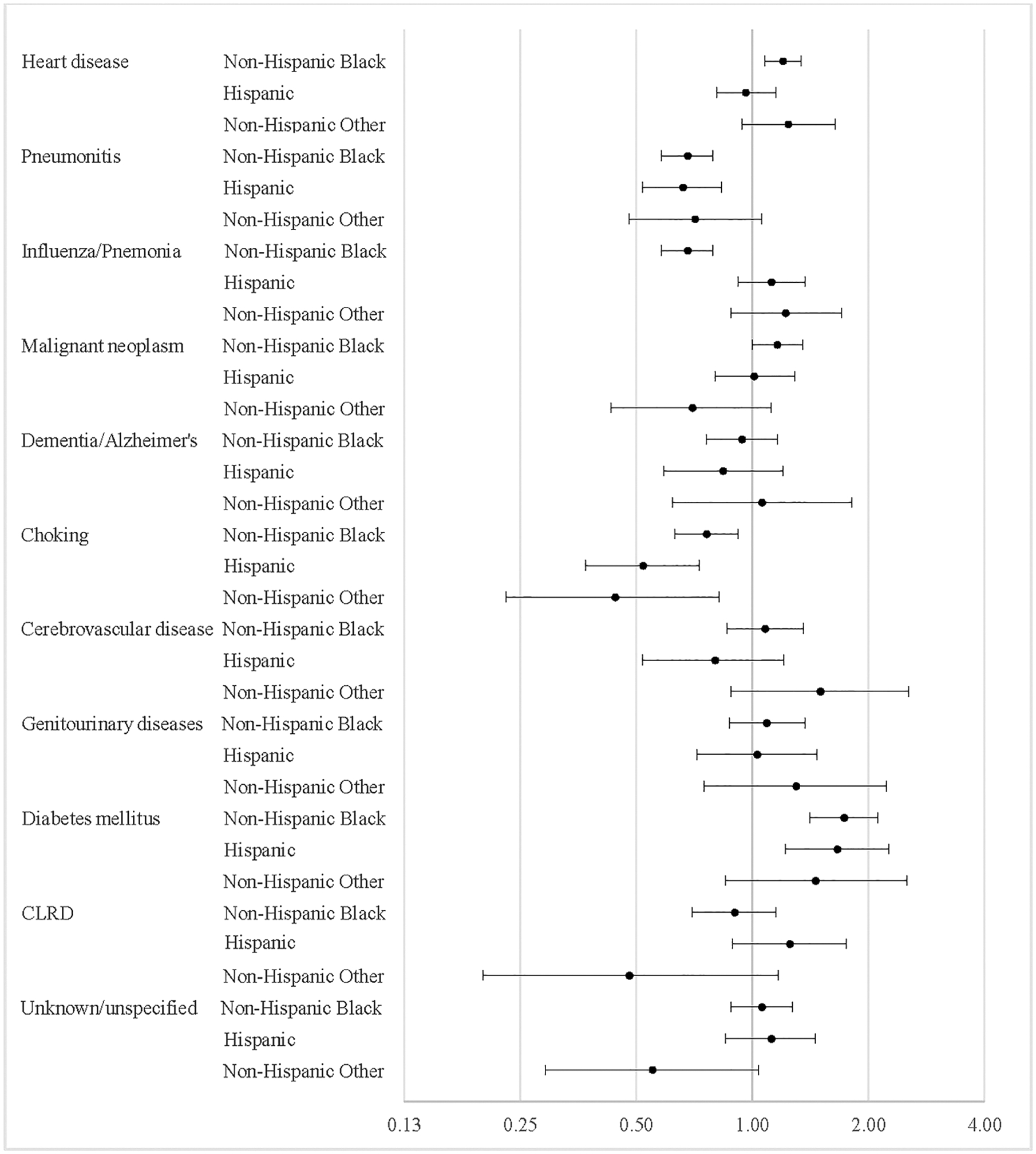

Although not as severe as in the general population (National Vital Statistics System 2017), among adults with ID, female individuals (62.3 years) had an age at death advantage over male individuals (60.1 years). Differences in age at death by race-ethnicity among adults with ID were similar to those seen in the general population (National Vital Statistics System 2017): Non-Hispanic Whites – 62.7 years; Non-Hispanic Blacks – 55.5 years; Hispanics – 52.8 years and Non-Hispanic Others – 53.8 years. To gain a better understanding of potential biological sex and racial-ethnic differences among adults with ID, we analysed whether these demographic characteristics had differential effects on the overall risk of dying from each specific cause of death (full results provided in Appendix S3). As is apparent in Fig. 5, compared with male individuals, female individuals with ID had increased risk of death from malignant neoplasms (AOR = 1.1; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.3) and dementia/Alzheimer’s disease (AOR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.3, 1.7), diabetes mellitus (AOR = 5.1; 95% CI = 3.4, 7.7) and unspecified/unknown causes (AOR = 1.2; 95% CI = 1.0, 1.3) but decreased risk of death from pneumonitis (AOR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.7, 0.9), choking (AOR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.7, 0.9) and chronic lower respiratory diseases (AOR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.7, 1.0). Figure 6 provides comparisons of cause of death risk between each racial-ethnic minority group and Non-Hispanic Whites. Among adults with ID, Non-Hispanic Blacks had higher risk of death from heart disease (AOR = 1.2; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.3) and diabetes mellitus (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.4, 2.1) but lower risk of death from pneumonitis (AOR = 0.7; 95% CI = 0.6, 0.8), influenza/pneumonia (AOR = 0.7; 95% CI = 0.6, 0.8) and choking (AOR = 0.7; 95% CI = 0.6, 0.9). Hispanics had higher risk of death from diabetes mellitus (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.2, 2.3) and lower risk of death from pneumonitis (AOR = 0.7; 95% CI = 0.5, 0.8) and choking (AOR = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.4, 0.7). Non-Hispanic Others also had lower risk of death from choking (AOR = 0.4; 95% CI = 0.2, 0.8).

Figure 5.

Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for causes of death for female individuals compared with male individuals for adults intellectual disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files (N = 22 512).

Figure 6.

Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for causes of death for racial-ethnic minorities compared with Non-Hispanic Whites for adults with intellectual disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality (N = 22 512).

Discussion

Using data from the National Vital Statistics System 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files, this study provides empirical evidence that adults who had ID indicated on their death certificate in the United States had comparatively distinctive causes of death. Results highlight the need for people with ID, their family and caregivers, and those who provide their medical care to attend to health risk related to causes of death typical in the general population, such as heart disease and cancer (Rubin and Crocker 2006). Yet this is not enough. It is also imperative for those adults with ID and those providing their medical and daily care to devote increased attention to signs and symptoms of pneumonitis, influenza/pneumonia and choking across the life course, regardless of the severity level of the disability. In addition, results from this study indicate the need for increased awareness of the higher risk of diabetes among adults with mild/moderate ID. While important to address these health concerns in all adults, there is also a need to be aware of increased risk of death among specific demographic groups within this population: female individuals – dementia/Alzheimer’s and diabetes mellitus; male individuals – pneumonitis, influenza/pneumonia, and choking; Non-Hispanic Whites – pneumonitis, choking; Non-Hispanic Blacks – heart disease, diabetes mellitus and Hispanics – diabetes mellitus.

While correctly classified as a respiratory disease in ICD-10, pneumonitis as a cause of death among adults with ID is more similar to choking, because both are likely related to a higher prevalence of dysphagia and/or swallowing disorders among this population. (Samuels and Chadwick 2006) Despite being a common diagnosis for adults with ID, these disorders receive little (Rubin and Crocker 2006) to no (Prasher and Janicki 2019) attention in standard texts that discuss the health needs of this population. This is concerning, especially as adults with ID in this study, no matter the level of severity of their disability, had substantially increased risk of dying from either pneumonitis or choking. Based upon these results, it is imperative that medical providers consistently screen all adults with ID for dysphagia and/or swallowing disorders and ensure that individuals with ID, as well as their families and care staff, receive needed education regarding proper oral intake and swallowing (Chadwick et al. 2006). In addition, public health and preventive care efforts should focus on raising awareness regarding the prevalence of aspiration and choking-related deaths and highlight practical steps for assessing swallowing and oral intake dysfunction.

Results from this study also confirm that individuals with ID have lower rates of death from cancer. However, it is important to note that although at a lower risk than the general population, cancer was still the second leading cause of death for adults with mild/moderate ID and the fourth leading cause of death for adults with severe/profound or unspecified ID. This is likely due to reduced access to tobacco, occupational and environmental hazards, and sexual activity (Lauer et al. 2015). Although odds ratios of cancer were much lower for adults with ID, it remained the fourth leading cause of death for adults with ID in this study. Odds ratios for chronic lower respiratory diseases were also lower for adults with severe/profound and unspecified ID but not adults with mild/moderate ID. While lower rates of cancer and chronic lower respiratory disease deaths may be because this population is often protected from hazardous health behaviours, such as smoking, lower cancer deaths also may related to shorter life spans, as the median age at death for adults with ID in this study was 62 and the median age of cancer diagnoses in the United States is 66 (National Cancer Institute 2015).

Once controlling for age, rates of death from dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease were slightly higher for adults with mild/moderate and unspecified but similar for those with severe/profound ID. There are two factors that must be noted when considering these results. First, the diagnosis of dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease typically occurs after the age of 65 (McMurtray et al. 2006). In addition, research demonstrates that diagnosis of dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease is ‘complex’ in adults with ID due to their pre-existing cognitive limitations (Strydom et al. 2007; Strydom et al. 2010). Thus, the finding of higher rates of death from dementia and/or Alzheimer’s is remarkable and may be an underestimate of the prevalence of these diseases among adults with ID.

This study improves our understanding of mortality trends for adults who had ID indicated on their death certificate in multiple ways. Our analysis provides a needed update on causes of death among US adults with ID. Moreover, the use of a sequential revision process for underlying causes of death data minimises the obscuring effect of coding ID as the underlying cause of death. Unlike most previous studies that rely on administrative data inclusive only of adults receiving formal support services, this study relies on census death certificate data inclusive of adults with IDs who do and do not receive formal support services. Thus, reported results are more current, accurately reflect mortality trends for adults with ID across the life course by severity level and differentiate cause of death risk by demographic characteristics. In addition, use of specific causes of death, as opposed to broader ICD-10 chapters, resulted in a more refined understanding of specific diseases causing death in this population.

Limitations

As has been argued in prior studies, it would be preferable to analyse cause of death trends utilising a national registry of individuals with ID (Hosking et al. 2016). However, in that this type of registry does not exist in the United States, we do not have that luxury. The other option is to utilise information from states on individuals who receive formal support services (Lauer and McCallion 2015). While a necessary strategy, this type of study is often geographically limited by the willingness of states to share data and does not capture individuals with ID who are not receiving formal support services. In contrast, US death certificate data provide robust geographic representation and likely include adults who do and do not receive formal support services. As is detailed thoroughly in the methods section, this is not an ideal strategy as it only captures 29–50% of the population of adults with an ID who died between 2005 and 2017. While a definite limitation, by combining multiple years of data, we were able to analyse a sizeable sample that allowed for comparisons between adults with and without ID. While we were able to differentiate cause of death trends by severity of ID, it is important to recognise that the majority of individuals with ID had their disability reported as ‘unspecified ID’. Thus, we were not able to determine the severity of their disability. Although it is not possible to formally analyse with this data, based upon these results, it is logical to think that those identified as having unspecified ID represent a combination of adults with mild/moderate and severe/profound levels of ID.

Conclusion

Compared with adults without ID, adults who had an ID indicated on their death certificate between 2005 and 2017, regardless of severity level of the ID, had an increased risk of death from pneumonitis, influenza/pneumonia and choking. In addition, adults with mild/moderate ID had a higher risk of death from diabetes than adults without ID. Results from this study demonstrate that future research on mortality trends among adults with ID will prove more informative when providing comparisons of specific cause of death trends with the general population and should attend to possible variation by severity of disability, age, biological sex and race-ethnicity. Further research is needed to discern whether adults with ID are protected from risk factors that lead to death from neoplasms, or whether lower overall cancer risk may, at least partially, be informed by earlier deaths among those with ID. In addition, further research is needed to discern possible reasons for the demographic differences in causes of death observed in this study.

Supplementary Material

Data S1. Appendix S1: Adjusted odds ratios for specific causes of death between adults with and without intellectual disability by level of disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files (N = 32,760,741)

Appendix S2: Adjusted odds ratios for causes of death by age stratified by intellectual disability status, 2013–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files (N = 13,332,871)

Appendix S3: Adjusted odds ratios for causes of death for adults with intellectual disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files (N = 22,512)

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Source of funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R03AG065638.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

References

- Chadwick DD, Jolliffe J, Goldbart J & Burton MH (2006) Barriers to caregiver compliance with eating and drinking recommendations for adults with intellectual disabilities and dysphagia. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 19, 153–62. [Google Scholar]

- Glover G, Williams R, Heslop P, Oyinlola J & Grey J (2017) Mortality in people with intellectual disabilities in England. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 61, 62–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron MP (2018) Deaths: leading causes for 2016. National Vital Statistics Reports 67, 1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop P, Blair PS, Fleming P, Hoghton M, Marriott A & Russ L (2014) The confidential inquiry into premature deaths of people with intellectual disabilities in the UK: a population-based study. The Lancet 383, 889–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop P & Glover G (2015) Mortality of people with intellectual disabilities in England: a comparison of data from existing sources. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 28, 414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking FJ, Carey IM, Shah SM, Harris T, Dewilde S, Beighton C et al. (2016) Mortality among adults with intellectual disability in England: comparisons with the general population. American Journal of Public Health 106, 1483–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicki MP, Dalton AJ, Henderson CM & Davidson PW (1999) Mortality and morbidity among older adults with intellectual disability: health services considerations. Disability and Rehabilitation 21, 284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SD, Stevens JD & Turk MA (2019a) Heterogeneity in age at death for adults with developmental disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 63, 1482–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SD, Stevens JD & Turk MA (2019b) Obscuring effect of coding developmental disability as the underlying cause of death on mortality trends for adults with developmental disability: a cross-sectional study using US Mortality Data from 2012 to 2016. BMJ Open 9, e026614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SD, Stevens JD & Turk MA (2020a) Cause of death in adults with Down syndrome in the US. Disability and Health Journal, 100947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SD, Turk MA & Lauer E (2020b) Recommendations for accurately reporting intellectual and developmental disabilities on death certificates. American Journal of Public Medicine. 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPlante MP & Carlson D (1996) Disability in the United States: Prevalence and Causes, 1992. US Department of Education, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research. [Google Scholar]

- Larson SA, Lakin KC, Anderson L, Kwak Lee N, Lee JH & Anderson D (2001) Prevalence of mental retardation and developmental disabilities: estimates from the 1994/1995 National Health Interview Survey Disability Supplements. American Journal on Mental Retardation 106, 231–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer E, Heslop P & Hoghton M (2015) Identifying and addressing disparities in mortality: US and UK perspectives. International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities 48, 195–245. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer E & McCallion P (2015) Mortality of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities from select US state disability service systems and medical claims data. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 28, 394–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurtray A, Clark DG, Christine D & Mendez MF (2006) Early-onset dementia: frequency and causes compared to late-onset dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 21, 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen OS & Wang J-D (1981) An alternative to the proportionate mortality ratio. American Journal of Epidemiology 114, 144–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (2015) Age and cancer risk [Online]. National Institutes of Health. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/age (retrieved 8 February 2019).

- National Vital Statistics System (2017) Underlying cause of death data [Online]. Available at: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. (retrieved 26 March 2020).

- O’Leary L, Cooper S-A & Hughes-McCormack L (2018) Early death and causes of death of people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 31, 325–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppewal A, Schoufour JD, Maarl HJKVD, Evenhuis HM, Hilgenkamp TIM & Festen DA (2018) Causes of mortality in older people with intellectual disability: results from the HA-ID study. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 123, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasher VP & Janicki MP (eds) (2019) Physical health of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin IL & Crocker AC (2006) Medical Care for Children & Adults With Developmental Disabilities. Paul H. Brookes Publishing, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels R & Chadwick DD (2006) Predictors of asphyxiation risk in adults with intellectual disabilities and dysphagia. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 50, 362–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR & Kliewer EV (1995) Estimating standardized mortality odds ratios with national mortality followback data. Epidemiology 6, 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strydom A, Livingston G, King M & Hassiotis A (2007) Prevalence of dementia in intellectual disability using different diagnostic criteria. British Journal of Psychiatry 191, 150–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strydom A, Shooshtari S, Lee L, Raykar V, Torr J, Tsiouris J et al. (2010) Dementia in older adults with intellectual disabilities – epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 7, 96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Trollor J, Srasuebkul P, Xu H & Howlett S (2017) Cause of death and potentially avoidable deaths in Australian adults with intellectual disability using retrospective linked data. BMJ Open 7, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KDK, Bastian BB & Arias E (2018) Deaths: final data for 2016. National Vital Statistics Reports 67, 1–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Rasmussen SA & Friedman JM (2002) Mortality associated with Down’s syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: a population-based study. The Lancet 359, 1019–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Appendix S1: Adjusted odds ratios for specific causes of death between adults with and without intellectual disability by level of disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files (N = 32,760,741)

Appendix S2: Adjusted odds ratios for causes of death by age stratified by intellectual disability status, 2013–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files (N = 13,332,871)

Appendix S3: Adjusted odds ratios for causes of death for adults with intellectual disability, 2005–2017 US Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality files (N = 22,512)