Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a common cause of catheter-related blood stream infections (CRBSI). The bacterium has the ability to form multilayered biofilms on implanted material, which usually requires the removal of the implanted medical device. A first major step of this biofilm formation is the initial adhesion of the bacterium to the artificial surface. Here, we used single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) to study the initial adhesion of S. aureus to central venous catheters (CVCs). SCFS performed with S. aureus on the surfaces of naïve CVCs produced comparable maximum adhesion forces on three types of CVCs in the low nN range (~ 2–7 nN). These values were drastically reduced, when CVC surfaces were preincubated with human blood plasma or human serum albumin, and similar reductions were observed when S. aureus cells were probed with freshly explanted CVCs withdrawn from patients without CRBSI. These findings indicate that the initial adhesion capacity of S. aureus to CVC tubing is markedly reduced, once the CVC is inserted into the vein, and that the risk of contamination of the CVC tubing by S. aureus during the insertion process might be reduced by a preconditioning of the CVC surface with blood plasma or serum albumin.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Pathogenesis, Materials science

Introduction

The gram-positive bacterium S. aureus is a common cause of medical device-related infections1. The bacterium has the ability to adhere to different kinds of artificial surfaces and to form multilayered biofilms, which are frequently not susceptible to antibiotic therapy2. A commonly used endovascular medical device is the central venous catheter (CVC), which is essential in everyday medical practice, especially in treating patients in intensive care units3. However, usage of CVCs is also associated with a substantial risk of bloodstream infections (BSIs), and S. aureus is currently the major etiological agent of catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs)4. Silicone and polyurethane (PU) are the most commonly used materials for CVC production5, with PU displaying a superior permanence over silicone, however, at the cost of increased bacterial colonization rates5. A number of studies were conducted in the 1980s and 1990s to elucidate the host and pathogen-related factors responsible for the adhesion of S. aureus to CVCs6–11. These studies identified cell wall-anchored/associated proteins as important adhesins of S. aureus to naïve catheters9,11,12. Studies carried out with Staphylococcus epidermidis demonstrated that adhesion of the bacterium to the implant material is also driven by surface hydrophobicity and -topology13–15, and this probably also holds true for S. aureus16. Other studies demonstrated that host factors deposited on catheters significantly affect the binding capacity of S. aureus to the polymer surfaces7–10,12,16. When inserted into the vasculature, CVC surfaces are rapidly (within seconds) covered by plasma proteins, which in turn alter the binding capacity of the bacterium to the implanted medical device17. However, there is a certain discrepancy in the literature about the impact of plasma surface coating on the adhesion behavior of S. aureus to PU/CVCs. While some studies reported a positive effect of plasma on the adhesion of S. aureus to CVCs9,18, others observed no18 or even a negative effect of plasma or serum on the ability of this bacterium to adhere to PU-based catheters12,16. However, based on S. aureus adhesion studies performed with untreated and explanted CVCs, it can be assumed that host factors deposited on the CVC upon implantation promote rather than decrease binding of S. aureus to the inserted intravascular device7,8.

In order to colonize the CVC and to form a biofilm, the bacterium first needs to get into contact with the medical device. This is likely to happen by different means. The bacterium might get into contact with the CVC while the catheter is inserted through the skin. Under these conditions, the bacterial cell residing on the skin is most likely getting into contact with the naïve surface of the CVC via physicochemical and capillary forces19,20. It is assumed that most CRBSI originating from short-term CVCs (in place < 10 days) are of cutaneous origin, and gain access extraluminally3. A second common route by which S. aureus may get into contact with the CVC is contamination of the fluid administered through the device. Under these conditions, native S. aureus cells are likely to get into contact with the luminal area of the CVC that is either undecorated (i.e. the rear tubing of the CVC) or decorated by plasma factors (i.e. the front tubing and the tip of the CVC). A third way of CVC colonization by S. aureus originates from remote sources of local infection via the bloodstream (hematogenous spread). Under these conditions, S. aureus cells that are decorated by plasma factors are likely to get into contact with a CVC surface that is covered with plasma factors as well. Only little information is available yet on how these colonization routes affect the adhesion kinetics between S. aureus and the implanted medical device. Similarly, the adhesion forces between the bacterial cell and this type of implant material, and particularly the impact of blood plasma on the initial adhesion of S. aureus to CVC surfaces, have to our knowledge not been determined yet. In order to fill these gaps, we applied here a single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) approach21 to determine the maximum adhesion forces and rupture lengths of viable, native and plasma-coated S. aureus cells to naïve and plasma coated PU-based CVCs.

Results and discussion

Surface characteristics of PU-based CVC tubing

Our earlier work demonstrated that the adhesion of staphylococci to abiotic surfaces is dominated by hydrophobic/hydrophilic interactions between bacterial cell wall components and the artificial surface22,23, and that S. aureus displays stronger adhesion forces on hydrophobic than on hydrophilic surfaces24. Another important factor that affects the binding capacity of S. aureus to an abiotic surface is surface topology25. We and others have shown that the adhesion of S. aureus to hydrophobized silicon wafers and titanium decreases significantly when the roughness of the surface is increased in the low nanometer (nm) range (≤ 20 nm)26,27, while variations in surface topography in the higher nm to micrometer (µm) range (≥ 350 nm) were reported to enhance the bacterial adhesion to a substratum28,29.

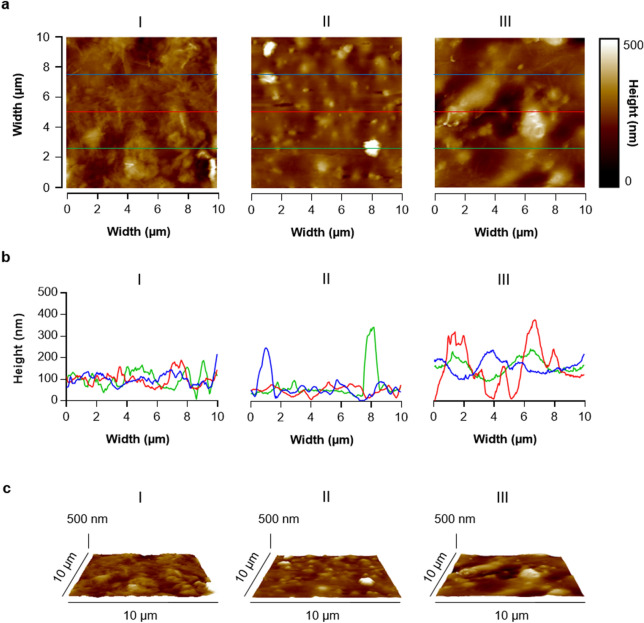

PU-based CVCs are currently the predominant catheter types used for central lines5, however, only little is known about the roughness and other surface characteristics of merchandised PU-based CVCs, which may additionally differ substantially between manufacturers. To further elucidate these characteristics, we started our study with the determination of the surface topography and hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity of three CVC types obtained from different manufacturers that are commonly used at the Saarland University Medical Hospital (Fig. 1 and Table 1). All three CVC types displayed advancing water contact angles 90° < Ɵ < 130° (Table 1), indicating that these surfaces are hydrophobic. Similarly, all three CVC tube surfaces exhibited a rather comparable overall roughness, with root mean square (RMS) roughness values between 51 and 58 nm (Table 1). However, the 10 µm × 10 µm height profiles recorded by AFM indicated that the three CVC types display differences in their surface topologies (Fig. 1). CVC surfaces of type III displayed noisy surface topologies with multiple small peaks and numerous bumps and valleys with height differences up to 500 nm. Type II CVC surfaces exhibited flatter surface topologies with a number of smaller but high bumps, and type I CVC surfaces displayed again more bumpy surface topologies, however, with the smallest variations between bumps and valleys (Fig. 1). When the skewness, the degree of asymmetry of a surface height distribution, was calculated from the AFM images, CVC surfaces of type II featured the highest skewness values, while CVC surfaces of types I and III displayed lower values that were in a comparable range (Table 1), in line with earlier findings suggesting CVC type II to exhibit a more irregular surface topology than CVC types I and III15.

Figure 1.

AFM height images of the surfaces of CVC types I to III. 10 × 10 µm areas of the CVC tubes were scanned by AFM as outlined in “Materials and methods” section. (a) Representative 2D AFM height images of the CVC types I to III. (b) Overlay of height profiles along the lines indicated in (a). (c) Representative 3D AFM height images of the same regions as displayed in (a).

Table 1.

Surface characteristics of the tubing of CVC types I–III.

| CVC type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | |

| Advancing water contact angle Ɵ (°) | 119 ± 6 | 109 ± 1 | 109 ± 1 |

| Root-mean-square roughness (nm) | 57.5 ± 6.9 | 50.8 ± 7.1 | 58.3 ± 18.3 |

| Skewness | 0.64 ± 0.77 | 1.69 ± 0.67 | 0.44.3 ± 0.1 |

Data are represented as mean ± SD.

S. aureus displays comparable adhesion forces on different types of PU-based CVC surfaces

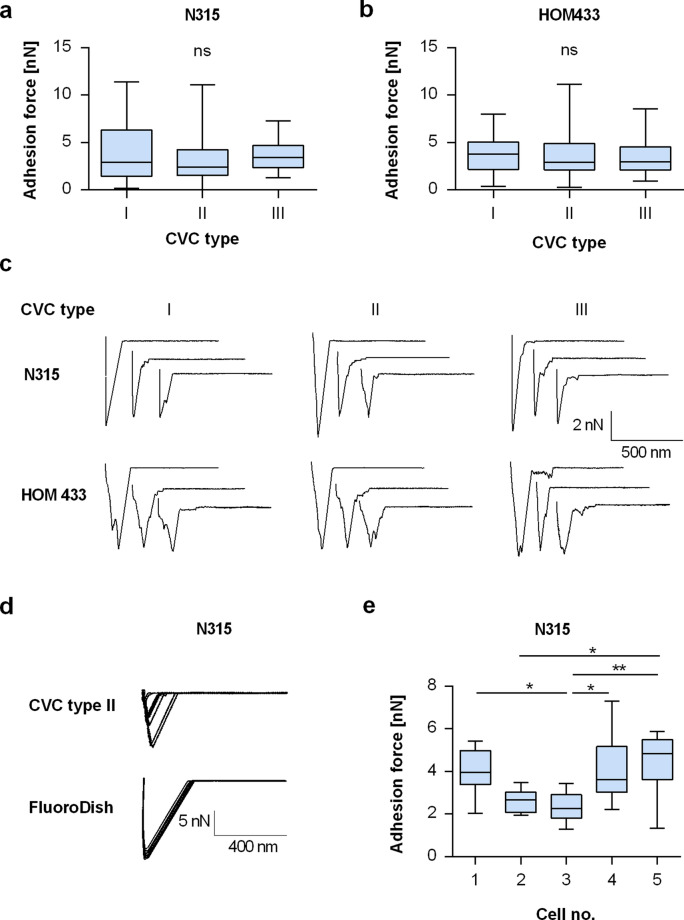

Although the quantitative and qualitative adhesion of staphylococci to CVCs has been addressed by many studies, the adhesion forces between S. aureus and this type of implant material have to our knowledge not been determined yet. Thus, we next studied the adhesion behavior of viable S. aureus cells to the CVC surfaces by SCFS, which allows measuring the interaction forces between a single bacterial cell and its substratum with pN force resolution21. In line with our surface characterization experiments (Fig. 1 and Table 1), we detected rather comparable maximum adhesion forces (Fadh) for S. aureus strain N315 on all three types of CVCs (Fig. 2a), which averaged between 3.1 ± 2.3 nN and 4.0 ± 2.9 nN (mean and SD). N315 cells tended to exhibit lower adhesion forces on the CVC surface of type II, however, this effect was not statistically significant. A similar trend was observed for the rupture lengths obtained with N315 on the CVC surface of type II, which were about half as long as the ones observed with this strain on the CVC surface of type III (Table S1).

Figure 2.

Adhesion kinetics of S. aureus on naïve CVC types I to III. Individual exponential growth phase cells of S. aureus were immobilized on cantilevers and used for SCSF on naïve surfaces of CVC types I to III. (a,b) Maximum adhesion forces extracted from the retraction curves recorded by SCFS with cells of strains N315 (a) and HOM433 (b) on the naïve surfaces of CVC types I to III. Data are presented as box and whisker plots (min-to-max) of 50 values obtained with 5 individual cells per strain. ns, not significant (Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test). (c) Representative retraction curves collected from cells that were probed with naïve CVC surfaces from manufacturers I to III. (d) Overlays of 10 retraction curves obtained with a single N315 cell on glass and the surface of CVC type II, respectively. (e) Maximum adhesion forces of cells of strain N315 on the surface of CVC type III. Data are presented as box and whisker plots showing the interquartile range (25–75%; box), median (horizontal line), and whiskers (bars; min/max) of 10 values obtained per individual cell. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test).

Since an earlier study noticed larger strain to strain variations in the capacity of S. aureus to adhere to CVC surfaces16, we conducted a second series of SCFS measurements with the CRBSI-related clinical isolate HOM433 to exclude that the findings made with N315 might be restricted to this strain. When cells of the clinical isolate were probed on the three naïve CVC surfaces, very similar Fadh values and rupture lengths were observed on the respective CVC types (Fig. 2b and Table S1). The vast majority of the recorded retraction curves obtained with the two isolates displayed a clear main detachment peak with only a few discrete steps (Fig. 2c), suggesting the involvement of numerous bacterial adhesins and a rather abrupt detachment of the bacterial cell surface components from the CVC surface23,24. The maximum adhesion forces recorded for S. aureus N315 on PU-based CVC surfaces in this study were in a similar range to those observed for this bacterium on silicone rubber30, and about a factor 10 higher than those found on titanium (J. Mischo, unpublished results), a commonly used material for orthopedic and dental implants31. This suggests that S. aureus exhibits a comparably strong binding capacity to naïve PU-based CVC surfaces.

In contrast to a previous report on the adhesion of S. aureus to hydrophobized Si wafers with a very smooth surface topography (RMS of 0.12 nm), where the force–distance measurements with an individual bacterial cell provided highly superimposable retraction curves23, we observed comparably large variations in the maximum adhesion forces recorded for some of the individual cells (Table S1). One reason for this might be the surface roughness of the CVCs tubes tested. In biophysical studies, SCFS is commonly carried out on highly defined and very smooth surfaces lacking larger bumps, while our test surfaces displayed numerous smaller and larger humps (Fig. 1). To access the impact of surface roughness on the adhesion force variation seen between repeated measurements with the identical bacterial probe, we additionally determined the maximum adhesion forces for N315 cells on FluoroDish, a hydrophobic glass surface32 displaying a low surface roughness (RMS = 1.1 ± 0.2 nm) and lacking any major humps. On this type of glass surface, N315 produced retraction curves and adhesion forces that were highly similar (Fig. 2d), suggesting that surface roughness might indeed be a factor contributing to the large variation in adhesion forces seen for individual S. aureus cells on the CVC surfaces in repeated measurements. Another explanation for this phenomenon might be chemical and biomechanical variations in surface composition. PU-based materials are formed in block copolymers creating a two phase microstructure composed of 10–100 nm microdomains with different physicochemical properties33. It has been shown that these microdomains display differences in the adsorption of plasma proteins and cell attachment34.

Similar to the variations in adhesion forces seen for repeated measurements with the same bacterial probe, we also noticed in part significant variations in the mean adhesion forces between individual cells (Fig. 2e and Table S1). This observation is rather common for SCFS studies with staphylococci22,24,26,31,35 and probably due to cell-to-cell variations that occur even between individual cells sampled from the same cell culture and at the same time point.

Precoating of the CVC surface with human blood plasma decreased the adhesion force of S. aureus to CVC surfaces

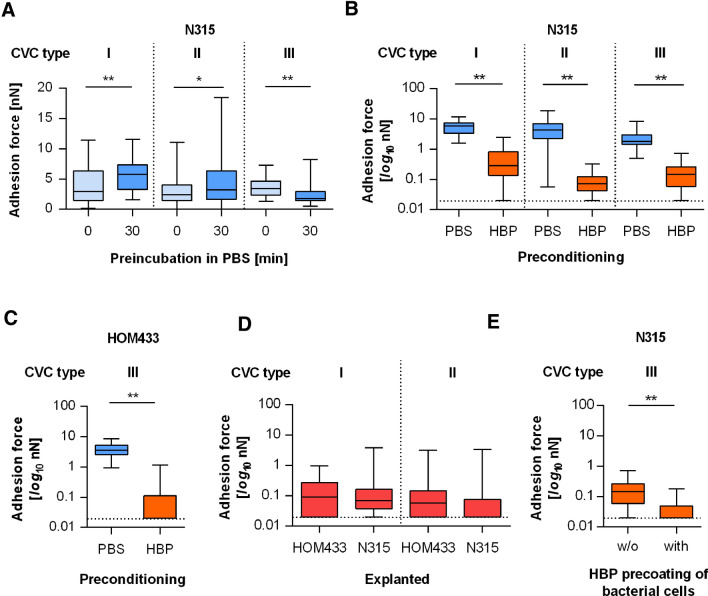

When inserted into the body, blood-exposed implanted materials are decorated within seconds by blood plasma factors36, but it is a matter of debate whether this positively or negatively affects the adhesion capacity of S. aureus to the implanted medical device9,16,18,37. Additionally, the impact of blood plasma on the initial adhesion of S. aureus to CVC surfaces has not been determined yet. In order to address this issue, we performed SCFS with S. aureus N315 on CVC fragments that were preincubated for 30 min with human blood plasma (HBP). Since PU-based materials are known to alter their surface properties in aqueous solutions34, we first determined the maximum adhesion forces for N315 on the surfaces of CVC tubes that were precultured for 30 min in PBS. Although no clear signs of swelling were observed for this comparably short time period, we noticed significant differences in the Fadh values on PBS preincubated CVC surfaces when compared to naïve CVC surfaces (Fig. 3A). This suggests that the contact with aqueous solutions for 30 min already alters the surface properties of PU-based CVCs in a way that promotes (CVC types I and II) or decreases (CVC type III) S. aureus adhesion.

Figure 3.

Adhesion kinetics of S. aureus on precoated CVC surfaces. Individual exponential growth phase cells of S. aureus strains N315 and HOM433 were used for SCSF on naïve and pretreated CVC surfaces. (A) Impact of a PBS preincubation (30 min) on the maximum adhesion forces of N315 cells on the surfaces of CVC types I to III. (B) Impact of a HBP preconditioning (30 min) on the maximum adhesion forces of N315 on the surfaces of CVC types I–III. (C) Impact of a HBP pretreatment (30 min) on the maximum adhesion forces of HOM433 on the surface of CVC type III. (D) Maximum adhesion forces of untreated N315 or HOM433 cells on the surface of freshly explanted CVCs of types I and II obtained from patients without CRBSI. (E) Impact of a HBP preconditioning of N315 cells on the maximum adhesion force of the bacterium formed on HBP-precoated surfaces of CVC type III. Data are presented as box and whisker plots (min-to-max) of 40–60 values obtained with 4–6 individual cells per condition. The detection limit of our system is indicated by horizontal dashed lines. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Mann Whitney U test).

When force–distance curves of strain N315 were recorded on catheter surfaces that were preincubated for 30 min with HBP, significant decreases in Fadh values were observed for all three CVC types (Fig. 3B), which dropped by ≥ tenfold when compared to the Fadh values obtained on the PBS preincubated CVC surfaces of the same type. To substantiate this observation, we carried out a second set of experiments with strain HOM433 on surfaces of CVC type III (Fig. 3C), which yielded a very similar result. These findings strongly suggest that the adhesion capacity of S. aureus to this type of medical device is drastically reduced, once the CVC is inserted into the vein, and support earlier work reporting a negative effect of plasma or serum on the adhesion of S. aureus to polymer materials12,16.

One factor that might explain the lower Fadh values observed for S. aureus on HBP-precoated CVC surfaces is surface hydrophobicity, as S. aureus displays a reduced adhesion capacity to hydrophilic surfaces24. Thus, we next determined the impact of a HBP preconditioning on the wettability of the CVC tubing. HBP-pretreated surfaces of CVC types I, II and III displayed advancing water contact angles of 55 ± 4°, 39 ± 4° and 51 ± 5°, respectively. These findings suggest that a HBP preconditioning renders the surface of the CVC tubing from hydrophobic to hydrophilic, and that this change in wettability might indeed contribute to the reduced maximum adhesion forces observed for S. aureus on the HBP-precoated CVC tubing. Specific receptor–ligand interactions between bacterial cell wall proteins and blood plasma factors deposited on the CVC tubing, on the other hand, seem to be of minor importance, albeit of the fact that S. aureus expresses a number cell wall-anchored or -associated adhesins capable of binding to blood plasma factors such as fibrinogen (Fg), fibronectin, immunoglobulin G, vitronectin, and von Willebrand factor (vWF), respectively38, which all were reported to adsorb onto the surfaces of implant materials upon contact of the foreign material with blood39,40.

S. aureus displayed low adhesion forces on explanted CVC tubings

Flow conditions and dwelling times are both known to affect the composition of the plasma factor coating on implanted materials36 and to induce conformational changes of the adsorbed proteins34. To see if and how our findings received with the in vitro HBP preincubated CVC surfaces can be matched with the in vivo situation, we next tested the adhesion forces of strains N315 and HOM433 on freshly explanted CVC tubing withdrawn from patients that did not suffer from CRBSI. When force–distance curves were recorded on this type of material, we observed maximum adhesion forces (Fig. 3D) that were very similar to the Fadh values determined with N315 and HOM433 on the in vitro HBP preincubated CVC surfaces (Fig. 3B,C), suggesting that our findings received with the in vitro test system can be correlated with the in vivo situation.

Coating of the S. aureus cell wall with HBP factors further reduced the adhesion force of the bacterial cell to the HBP-precoated CVC surface

A third route of CVC colonization by S. aureus originates from hematogenous spreading of the bacterium from other infection foci41. Under these conditions, S. aureus cells that are decorated by plasma factors and/or attached to blood cells get into contact with a CVC surface that is covered with plasma factors and blood cells as well. In order to mimic this scenario, we preincubated N315 cells for 30 min with HBP before we recorded the force–distance curves with such cells on HBP-precoated CVC fragments of type III (Fig. 3E). The preconditioning of the bacterial cell with HBP further reduced the maximum adhesion force between N315 and the HBP-precoated CVC surface, when compared to the adhesion forces observed for uncoated N315 cells on HBP preincubated CVC surfaces. These findings suggest that blood borne S. aureus cells exhibit a rather lower adhesion capacity to CVC surfaces inserted into the vasculature, at least under static conditions. However, our experimental setup lacks at least two major factors relevant for the adhesion of S. aureus to implant material that is inserted into the vasculature, which are the presence of blood cells, e.g. platelets bound to the catheter surface that might be exploited by the bacterium for adhesion, and shear flow. S. aureus cells are reported to adhere to platelets with high efficiency42, and platelets adhere to implanted material inserted into the bloodstream43. Although it is unknown yet to which extent S. aureus adheres to blood-exposed implant material via platelets, it can be assumed that platelets contribute to the adhesion and biofilm formation of S. aureus to/on CVCs, given the interplay between S. aureus and this type of blood cells42. Another factor that is likely to be important for the binding capacity of S. aureus to implant material that is inserted into the vasculature is shear flow. Most regions of the CVC tubing that are inserted into larger veins are exposed to high shear stress44, and we and others have shown that binding of S. aureus to activated endothelium under high shear flow is mediated predominantly via elongated vWF fibers45,46. vWF unfolding is only observed when vWF is tethered to a surface and exposed to high shear stress47. vWF is also known to adsorb on blood-exposed catheters40. Although vWF seems to be of minor importance for platelet adhesion on blood-exposed implant material48, its elongated form is likely to contribute to the adhesion capacity of S. aureus to the blood-exposed implant material under high shear flow. To access such shear flow-induced phenomena, the actual flow profile must be precisely determined (e.g. in a microfluidic setup with particle imaging velocimetry), which is beyond the scope of the present study.

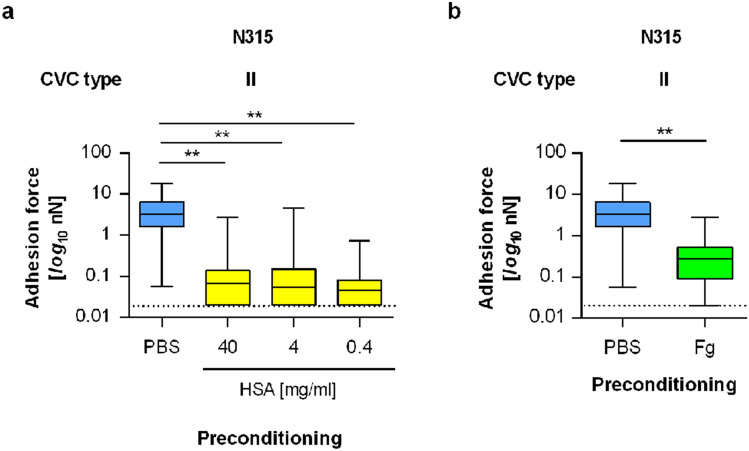

The adhesion force of S. aureus to CVC surfaces is reduced by a preincubation of the CVC tubing with serum albumin or Fg

Serum albumin and Fg are the main proteinaceous plasma factors that are adsorbed on blood-exposed polymer surfaces49, and the preincubation of a CVC with serum albumin has been shown to reduce the adhesion of S. aureus to the CVC surface8. In line with the latter publication, we also found a strong decrease in the maximum adhesion forces between S. aureus N315 and the catheter surface of type II when the catheter fragment was preincubated with human serum albumin (HSA; Fig. 4a). The adhesion forces of N315 on the CVC surface dropped by a factor of about 35 when the catheter fragments were preincubated with 40 mg/ml of HSA, a common albumin concentration found in human blood50. Notably, similar reductions in the mean Fadh values were observed even when HSA concentrations as low as 0.4 mg/ml were used for preincubation (Fig. 4a), suggesting that much lower concentrations of this blood plasma protein than the ones usually found in human blood are sufficient to markedly suppress the initial adhesion capacity of S. aureus N315 to PU-based CVC surfaces.

Figure 4.

Impact of HBP-factors on the adhesion of S. aureus to CVC tubing. Individual exponential growth phase cells of S. aureus strain N315 were used for SCSF on naïve and pretreated tubing of CVC type II. (a) Impact of human serum albumin (HSA) on the maximum adhesion forces of untreated N315 cells formed on HSA (0.4, 4, and 40 mg/ml for 30 min) pretreated CVC surfaces. (b) Impact of human fibrinogen (Fg) on the maximum adhesion forces of untreated N315 cells formed on Fg (0.4 mg/ml for 30 min) precoated CVC surfaces. Data are presented as box and whisker plots (min-to-max) of 60 values obtained with 6 individual cells per condition. The detection limit of our system is indicated by dashed lines. **P < 0.01 (Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test [a] or Mann Whitney U test [b]).

A smaller, but still highly significant reduction in mean Fadh values was also observed when N315 cells were probed with CVC fragments of type II that were preincubated with physiological concentrations of human Fg (Fig. 4b). The latter observation is surprising since earlier work reported positive effects of Fg on the adhesion capacity of S. aureus to implanted materials in quantitative adhesion assays7,51. Given these differences in the impact of Fg on the qualitative and quantitative adhesion of S. aureus to implanted material in vitro, we hypothesize that a decoration of the CVC surface with physiological concentrations of Fg reduce the interaction force between S. aureus and the implanted material, while the quantitative adhesion capacity of S. aureus to this type of implanted material is promoted by the presence of this host factor on the CVC surface. This scenario might also hold true for human blood plasma factors adsorbed on the CVC surface, which were found here to strongly decrease the adhesion forces between S. aureus and PU-based CVCs, while others observed enhanced numbers of S. aureus cells on different types of catheter surfaces that were withdrawn from patients8. However, in the latter study, the quantitative adhesion of S. aureus to explanted catheter fragments was compared to catheter fragments that were precoated with serum albumin, leaving the question open to which extent S. aureus would have adhered to the respective naïve catheter fragments.

Concluding remarks

To our knowledge, this is the first time that SCFS with S. aureus was done on authentic, commercially available CVC material to determine the adhesion forces between a commonly used implanted medical device and this major nosocomial pathogen. We showed that S. aureus binds with high affinity to PU-based CVC tubing and that this adhesion can be markedly reduced by a pretreatment of the CVC tubing with blood plasma or serum albumin. The preconditioning of the CVC surface with serum albumin, a procedure suggested to reduce the risk of thrombus formation on blood exposed medical devices52, might also be a valid tool to decrease the risk of contamination of the CVC tubing with S. aureus, particularly during the insertion process. The reduced adherence strength of S. aureus cells to blood plasma precoated PU-based CVC tubing is probably due to a decrease in surface hydrophobicity of the implant material evoked by the adsorbed plasma factors. This assumption is in line with earlier findings made with S. aureus and different types of venous catheters demonstrating that chemical modifications which rendered the catheters more hydrophilic also decreased the quantitative adhesion of the bacterium to the modified surfaces18,53,54, and supports the idea that increasing the hydrophilicity of PU-based CVC tubing might be a valuable tool to lower the risk of bacterial colonization of this implanted medical device6. Our data suggest furthermore that a chemical modification of the tubing surface might not be needed to achieve this goal.

Materials and methods

Bacteria and bacterial probes

S. aureus strain N315 was obtained from the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in S. aureus (NARSA) strain collection (Catalog Number: NRS70). The clinical S. aureus isolate HOM433 was collected from a CVC that was removed from a patient suffering from a catheter-related S. aureus blood stream infection at the Saarland University Hospital, Homburg, Germany. The bacteria were grown on Tryptic Soy Agar Plates with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson [BD], Heidelberg, Germany), and subsequently multiplied in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, BD) in Erlenmeyer flasks using a culture to flask volume of 1:10 for 16 h at 37 °C and 150 rpm. On the next day, the bacterial cell number was set to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.05 in TSB and bacterial cells were grown for 2.5 h at 225 rpm to the exponential growth phase. After harvesting, bacterial cells were centrifuged for 1 min at 12,000 rpm and were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to remove debris and extracellular material. Bacteria were then prepared for AFM and diluted 1:50 in PBS, where bacterial aggregates were separated with an ultrasonic probe (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) for 15 s at 50 W. Next, a single bacterium was attached to a polydopamine-coated tipless AFM cantilever (MLCT-0 with a nominal spring constant of 0.03 N m−1 from Bruker-Nano, Santa Barbara, USA) via a micromanipulator (Narishige Group, Tokyo, Japan) as described in21. The functionalization of the cantilever was controlled optically with an inverted microscope and by force–distance measurement on a glass-bottomed petri dish (FluoroDish FD35-100; World Precision Instruments, Friedberg, Germany). The viability of the bacterial cell at the end of the force/distance measurements was confirmed by live/dead staining using the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany).

Human samples

Human blood was obtained from healthy volunteers older than 18 years of age. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. Explanted CVCs were obtained from the Department of Internal Medicine V, Pneumology and Intensive Care Medicine, Saarland University, Homburg, Germany. The study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association of Saarland (code numbers 95/18 and 39/20) before recruitment and study initiation. The study was performed according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The acquisition procedures of blood and explanted CVC samples, respectively, were checked and approved by the local ethics committee.

Substrate preparation

CVC tubing samples were prepared from the Arrow CVC set DE-14703-S (Teleflex Medical GmbH, Fellbach [type I]), B. Braun Certofix Trio S 720 (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany [type II]), and Vygon Seldipur Safe (Vygon, Aachen, Germany [type III]). Catheter packages were opened and CVCs handled in a level 2 biosafety cabinet to reduce contaminant deposition on the catheter surface. The CVC tubing was cut with a sharp scalpel into ~ 0.5 cm fragments, and single fragments were attached to a flat glass-bottom petri dish with a water-resistant glue (Pattex, Düsseldorf, Germany), which was allowed to harden for 30 min under the BSC to strengthen the fixation between catheter and glass surface. For the fixation of explanted CVC fragments, sample fixation was done the same way, but the glass petri dish was additionally placed in a humidity chamber to prevent the biological coating on the CVC from drying. HBP was derived from freshly withdrawn blood collected in S-Monovette lithium-heparin blood collection tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) that was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 2 min. HBP was transferred to a fresh reaction tube, centrifuged one more time under the same conditions to remove any cell material, and then stored in a fresh reaction tube at − 80 °C until usage.

Surface characterization of the CVC tubing

For mapping of the height topography of the CVC tubing, fragments of the three CVC types were scanned in PBS in Peak Force Tapping intermittent contact mode with an atomic force microscope (Bioscope Catalyst; Bruker Nano). For measurements in PBS, silicon nitride tips (SNL-10 with nominal spring constant of 0.35 N/m from Bruker-Nano) were used. Typically, an area of 10 µm × 10 µm (256 × 256 pixels) was scanned with a scan rate set to 0.1 Hz. The resulting images were flattened (second order) and plane fitted (first order), and used to determine roughness parameters with the Nanoscope Analysis software 1.9 (Bruker Nano). Water contact angle determinations on CVC surfaces were done as follows: From each CVC type, 2 cm long pieces were cut off and mounted on a straight needle. Pieces were immersed into ultrapure water at a constant velocity of 1 mm/s using an automated setup. At the same time, the water surface around the CVC pieces was recorded with a camera from the direction perpendicular to the line of movement at frame rates of 10 frames per second. Afterwards, the CVC pieces were placed in HBP for 30 min at 37 °C, subsequently rinsed 8-times with water, and the wettability of the precoated surfaces recorded as described above. The water contact angles before and after plasma coating were determined from every frame of the recorded movies using a self-written Matlab script in which the edge of the CVC was fitted with a linear function and the water surface with a third-order polynomial.

Single-cell force spectroscopy

CVC fragments were attached to flat-bottom glass petri dishes as outlined above, covered with PBS, and measurements were started within five min to mimic the adhesion of single bacterial cells to the naïve surface. The bacterial probe was placed above the center of the catheter, and carefully approached towards the surface. 10 force–distance curves were recorded per bacterial probe on the crest of each CVC fragment with a force trigger set to 300 pN, a lateral distance between two force–distance curves set to 1 µm, the ramp velocity adjusted to 160 nm/s and a ramp size of 800 nm. For the preconditioning of the CVC tubing with HBP (derived from whole blood withdrawn from at least three healthy volunteers), HSA (purchased from Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), or human Fg (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), fixed CVC pieces were covered with a droplet of HBP, HSA (0.4, 4, and 40 mg/ml), or Fg (0.4 mg/ml), respectively, incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, and subsequently washed eight times with PBS to remove loosely attached plasma factors/proteins that might distort the AFM measurements. Precoated CVC fragments were again covered in PBS, and force–distance curves recorded as outlined above. Analysis and depiction of force–distance curves were done with the Nanoscope Analysis software and OriginPro 2019b (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

Statistical analyses

The statistical significance of changes between groups was assessed with Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by Dunn’s post-hoc tests (3 and more groups) or the Mann–Whitney U test (two groups) using the GraphPad software package Prism 6.01. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the German Research Foundation Grants SFB 1027/B1 to B3, the Max Planck School Matter to Life supported by the German Federal Ministery of Education and Research (BMBF) in collaboration with the Max Planck Society, and Saarland University within the funding program Open Access Publishing. We are grateful to Mathias Herrmann for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

Author contributions

M.B., S.B., M.H., and K.J. designed the research. G.G., P.J. C.S. and M.B. analyzed data. G.G., S.T., C.S., B.W., and J.M. were responsible for the experimental work. C.M. provided material. M.B. and G.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/4/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-021-89018-5

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-77168-x.

References

- 1.Hogan S, Stevens NT, Humphreys H, O'Gara JP, O'Neill E. Current and future approaches to the prevention and treatment of staphylococcal medical device-related infections. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015;21:100–113. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140905123900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lebeaux D, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. Biofilm-related infections: bridging the gap between clinical management and fundamental aspects of recalcitrance toward antibiotics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2014;78:510–543. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00013-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safdar N, Maki DG. Inflammation at the insertion site is not predictive of catheter-related bloodstream infection with short-term, noncuffed central venous catheters. Crit. Care Med. 2002;30:2632–2635. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000037966.19604.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai YL, et al. Dwindling utilization of central venous catheter tip cultures: an analysis of sampling trends and clinical utility at 128 US hospitals, 2009–2014. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019;69:1797. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wildgruber M, et al. Polyurethane versus silicone catheters for central venous port devices implanted at the forearm. Eur. J. Cancer. 2016;59:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francois P, et al. Physical and biological effects of a surface coating procedure on polyurethane catheters. Biomaterials. 1996;17:667–678. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)86736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaudaux P, et al. Fibronectin is more active than fibrin or fibrinogen in promoting Staphylococcus aureus adherence to inserted intravascular catheters. J. Infect. Dis. 1993;167:633–641. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaudaux P, et al. Host factors selectively increase staphylococcal adherence on inserted catheters: a role for fibronectin and fibrinogen or fibrin. J. Infect. Dis. 1989;160:865–875. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.5.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung AL, Fischetti VA. The role of fibrinogen in staphylococcal adherence to catheters in vitro. J. Infect. Dis. 1990;161:1177–1186. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett SP. Protein-mediated adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus to silicone implant polymer. J. Med. Microbiol. 1985;20:249–253. doi: 10.1099/00222615-20-2-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espersen F, Wilkinson BJ, Gahrn-Hansen B, Thamdrup Rosdahl V, Clemmensen I. Attachment of staphylococci to silicone catheters in vitro. APMIS. 1990;98:471–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1990.tb01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulsson M, et al. Adhesion of staphylococci to chemically modified and native polymers, and the influence of preadsorbed fibronectin, vitronectin and fibrinogen. Biomaterials. 1993;14:845–853. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(93)90006-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludwicka A, Jansen B, Wadstrom T, Pulverer G. Attachment of staphylococci to various synthetic polymers. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. A. 1984;256:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0174-3031(84)80024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locci R, Peters G, Pulverer G. Microbial colonization of prosthetic devices. III. Adhesion of staphylococci to lumina of intravenous catheters perfused with bacterial suspensions. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. B. 1981;173:300–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tebbs SE, Sawyer A, Elliott TS. Influence of surface morphology on in vitro bacterial adherence to central venous catheters. Br. J. Anaesth. 1994;72:587–591. doi: 10.1093/bja/72.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kristinsson KG. Adherence of staphylococci to intravascular catheters. J. Med. Microbiol. 1989;28:249–257. doi: 10.1099/00222615-28-4-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldmann DA, Pier GB. Pathogenesis of infections related to intravascular catheterization. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;6:176–192. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.John SF, Derrick MR, Jacob AE, Handley PS. The combined effects of plasma and hydrogel coating on adhesion of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus to polyurethane catheters. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1996;144:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitano T, et al. The role of physicochemical properties of biomaterials and bacterial cell adhesion in vitro. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 1996;19:353–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper GL, Schiller AL, Hopkins CC. Possible role of capillary action in pathogenesis of experimental catheter-associated dermal tunnel infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1988;26:8–12. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.1.8-12.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thewes N, et al. A detailed guideline for the fabrication of single bacterial probes used for atomic force spectroscopy. Eur. Phys. J. E. Soft Matter. 2015;38:140. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2015-15140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thewes N, et al. Hydrophobic interaction governs unspecific adhesion of staphylococci: a single cell force spectroscopy study. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2014;5:1501–1512. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.5.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thewes N, et al. Stochastic binding of Staphylococcus aureus to hydrophobic surfaces. Soft Matter. 2015;11:8913–8919. doi: 10.1039/c5sm00963d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spengler C, Thewes N, Jung P, Bischoff M, Jacobs K. Determination of the nano-scaled contact area of staphylococcal cells. Nanoscale. 2017;9:10084–10093. doi: 10.1039/c7nr02297b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crawford RJ, Webb HK, Truong VK, Hasan J, Ivanova EP. Surface topographical factors influencing bacterial attachment. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;179–182:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spengler C, et al. Strength of bacterial adhesion on nanostructured surfaces quantified by substrate morphometry. Nanoscale. 2019;11:19713–19722. doi: 10.1039/c9nr04375f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Truong, V. K. et al. Bacterial attachment response on titanium surfaces with nanometric topographic features. In: Trends in Colloid and Interface Science XXIII. Progress in Colloid and Polymer Science, 137, 41 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010).

- 28.Taylor RL, Verran J, Lees GC, Ward AJ. The influence of substratum topography on bacterial adhesion to polymethyl methacrylate. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1998;9:17–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1008874326324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mei L, Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC, Ren Y. Influence of surface roughness on streptococcal adhesion forces to composite resins. Dent. Mater. 2011;27:770–778. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muszanska AK, et al. Bacterial adhesion forces with substratum surfaces and the susceptibility of biofilms to antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4961–4964. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00431-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aguayo S, Donos N, Spratt D, Bozec L. Nanoadhesion of Staphylococcus aureus onto titanium implant surfaces. J. Dent. Res. 2015;94:1078–1084. doi: 10.1177/0022034515591485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faust JJ, Christenson W, Doudrick K, Ros R, Ugarova TP. Development of fusogenic glass surfaces that impart spatiotemporal control over macrophage fusion: direct visualization of multinucleated giant cell formation. Biomaterials. 2017;128:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodman SL, Cooper SL, Albrecht RM. Polyurethane support films: structure and cellular adhesion. Scanning Microsc. Suppl. 1989;3:285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu LC, Bauer JW, Siedlecki CA. Proteins, platelets, and blood coagulation at biomaterial interfaces. Colloids Surf. B. 2014;124:49–68. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maikranz E, et al. Different binding mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus to hydrophobic and hydrophilic surfaces. Nanoscale. 2020 doi: 10.1039/D0NR03134H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baier RE. The organization of blood components near interfaces. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1977;283:17–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb41750.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaudaux P, Suzuki R, Waldvogel FA, Morgenthaler JJ, Nydegger UE. Foreign body infection: role of fibronectin as a ligand for the adherence of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 1984;150:546–553. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foster TJ. Surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0046-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrade JD, Hlady V. Plasma protein adsorption: the big twelve. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987;516:158–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb33038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bailly AL, et al. Fibrinogen binding and platelet retention: relationship with the thrombogenicity of catheters. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1996;30:101–108. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199601)30:1<101::aid-jbm13>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crnich CJ, Maki DG. The promise of novel technology for the prevention of intravascular device-related bloodstream infection. I. Pathogenesis and short-term devices. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;34:1232–1242. doi: 10.1086/339863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeaman MR, Sullam PM, Dazin PF, Norman DC, Bayer AS. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus-platelet binding by quantitative flow cytometric analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 1992;166:65–73. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaffer IH, Fredenburgh JC, Hirsh J, Weitz JI. Medical device-induced thrombosis: what causes it and how can we prevent it? J. Thromb. Haemost. 2015;13(Suppl 1):S72–81. doi: 10.1111/jth.12961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng L, et al. Numerical simulation of hemodynamic changes in central veins after tunneled cuffed central venous catheter placement in patients under hemodialysis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:15955. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12456-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pappelbaum KI, et al. Ultralarge von Willebrand factor fibers mediate luminal Staphylococcus aureus adhesion to an intact endothelial cell layer under shear stress. Circulation. 2013;128:50–59. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.113.002008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Claes J, et al. Clumping factor A, von Willebrand factor-binding protein and von Willebrand factor anchor Staphylococcus aureus to the vessel wall. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2017;15:1009–1019. doi: 10.1111/jth.13653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Ceunynck K, De Meyer SF, Vanhoorelbeke K. Unwinding the von Willebrand factor strings puzzle. Blood. 2013;121:270–277. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-442285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai WB, Grunkemeier JM, McFarland CD, Horbett TA. Platelet adhesion to polystyrene-based surfaces preadsorbed with plasmas selectively depleted in fibrinogen, fibronectin, vitronectin, or von Willebrand’s factor. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002;60:348–359. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kochwa S, Litwak RS, Rosenfield RE, Leonard EF. Blood elements at foreign surfaces: a biochemical approach to the study of the adsorption of plasma proteins. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1977;283:37. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb41751.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson NL, Anderson NG. The human plasma proteome: history, character, and diagnostic prospects. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2002;1:845–867. doi: 10.1074/mcp.r200007-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herrmann M, et al. Fibronectin, fibrinogen, and laminin act as mediators of adherence of clinical staphylococcal isolates to foreign material. J. Infect. Dis. 1988;158:693–701. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eberhart RC, et al. Influence of endogenous albumin binding on blood-material interactions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987;516:78–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb33032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chauhan A, et al. Preventing biofilm formation and associated occlusion by biomimetic glycocalyxlike polymer in central venous catheters. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;210:1347–1356. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith RS, et al. Vascular catheters with a nonleaching poly-sulfobetaine surface modification reduce thrombus formation and microbial attachment. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:153ra132. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.