Abstract

Background:

Brain organoids are self-organized from human pluripotent stem cells and developed into various brain region following the developmental process of brain. Brain organoids provide promising approach for studying brain development process and neurological diseases and for tissue regeneration.

Methods:

In this review, we summarized the development of brain organoids technology, potential applications focusing on disease modeling for regeneration medicine, and multidisciplinary approaches to overcome current limitations of the technology.

Results:

Generations of brain organoids are categorized into two major classes by depending on the patterning method. In order to guide the differentiation into specific brain region, the extrinsic factors such as growth factors, small molecules, and biomaterials are actively studied. For better modelling of diseases with brain organoids and clinical application for tissue regeneration, improvement of the brain organoid maturation is one of the most important steps.

Conclusion:

Brain organoids have potential to develop into an innovative platform for pharmacological studies and tissue engineering. However, they are not identical replicas of their in vivo counterpart and there are still a lot of limitations to move forward to clinical applications.

Keywords: Brain organoid, Vascularization, Disease modeling, Tissue regeneration

Introduction

The brain is arguably the most important and complex organ in the human body. Understanding of full complexity of human brain, in action and in context, is the neurobiologists’ dream, but there is still a long way to go. The main limitation of studying human brain is the lack of model which faithfully recapitulates the pathophysiological features of the human brain. The most physiologically relevant brain model is known to be the primary cells isolated from patient brain tissue, given that laboratory animals are not always good proxies for human brain [1, 2]. However, in general, human brain tissue is hard to obtain and a cultured neuronal network has short life span.

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) overcome many of these limitations [3]. Especially, since human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSCs) emerged as easily accessible stem cell sources from normal and brain disorder patients, hiPSC-derived brain cells have been used for drug discovery and neurological disease research including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [4], Parkinson disease (PD) [5], and autism spectrum [6]. Many brain diseases are of diverse etiologies and complicated by variable genetic and epigenetic background, in that sense, patient-derived hiPSCs enable to study individual pathophysiological properties. Even though, the emergence of hiPSCs is revolutionizing brain research [7], two-dimensional (2D) brain cell models generated from hiPSCs are still far from reality considering the high cellular complexity and network geometry of the human brain.

Recent development of brain organoid offers a promising approach for investigating the brain development and neurological diseases showing closer approximation of brain tissue [8]. Brain organoids are self-organized from hPSCs and developed into various brain region following the same basic intrinsic patterning events as the organ itself [8], which is different from including neurosphere and neural spheroid. The three-dimensional (3D) cultures of neurons are suspension culture of cell aggregates made of differentiated neural cells, neural progenitor cells, or neural stem cells mirroring the basic processes of brain development, namely proliferation, migration, differentiation and apoptosis [9, 10]. On the other hand, brain organoids exhibit complex 3D arrangements of multiple cell types of neuron at a considerable level of detail [11, 12], therefore, are increasingly used in modeling neurological disorders.

In this review, we will describe the current status of brain organoids technology and potential applications focusing on disease modeling for regeneration medicine. Finally, we will introduce new technologies to develop more powerful brain organoids to move forward to clinical application.

Generation of hPSC-derived brain organoid: Current approaches

In order to generate the brain organoids, embryoid bodies (EBs); 3D aggregates of PSCs are formed and induced to differentiate into neuroectodermal tissue. Current brain organoid protocols are categorized into two major classes by depending on the differentiation method; (1) self-patterning method relying on the intrinsic self-organization capability which generates whole-brain organoid, and (2) pre-patterning method directing toward a certain identity by regulating the extrinsic factors with a variety of combinations [13, 14]. In addition, pre-patterning method is expanded to generation of assembloid by mixing of multiple brain region-specific organoids.

Self-patterned whole brain organoids

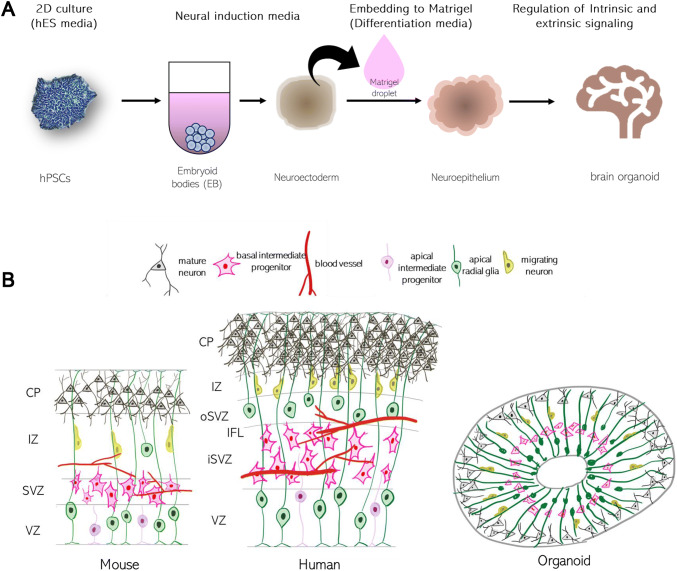

The well organized and validated protocol was reported in 2013 by Lancaster and his colleagues inspired by methodologies for human gut organoid [11]. In the protocol, hPSCs were aggregated in low-attachment 96-well plate forming EBs and fed with a neural induction media which promotes the development of neural ectoderm tissues. The generated neuroectodermal tissues were transferred to Matrigel droplet to provide the 3D tissue scaffold and fed with maintenance media [11] (Fig. 1A). These organoids mimic many aspects of structure and gene expression of early developing human cortex showing outer subventricular zones (oSVZ) separated by an inner fiber layer (IFL) like layer [15, 16] (Fig. 1B). Because of the minimal extrinsic interference, the organoids allow hPSCs the most freedom for self-organization exhibiting a variety of cell lineages from forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain, to retina, choroid plexus and mesoderm. Although hPSC spontaneous differentiation offers the generation of diversity of cell types, the high heterogeneity become challenge for many quantitative studies. Also, there are some drawbacks including incomplete cytoarchitecture of the basal zones and layers, and cell death at later stages limiting the full maturation of synapses [11]. Biomaterials can be used to guide the self-organization in controlled way. Lancaster et al. suggested the poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) copolymer fiber microfilaments as a floating scaffold to generate elongated embryoid bodies [17]. The microfilament-engineered cerebral organoid displayed enhanced neuroectoderm formation and improved cortical development by leading to polarized cortical plate and radial units [17].

Fig. 1.

A Schematic of the brain organoid protocol. B Comparison of in vivo and in vitro neurodevelopment. Neuronal stem cells (radial glia) are located and become mature neurons in the ventricular zone (VZ). Distinctive from mouse brain, the subventricular zone (SVZ) is divided into inner and outer regions in human brain. The cortical plate (CP) of human is developed into complex six-layers and is one of the distinct characteristics compared with mouse. Because of the absence of blood vessel, late neurodevelopment process is not fully recapitulated in brain organoids [14]. Reproduced with permission of COMPANY OF BIOLOGISTS

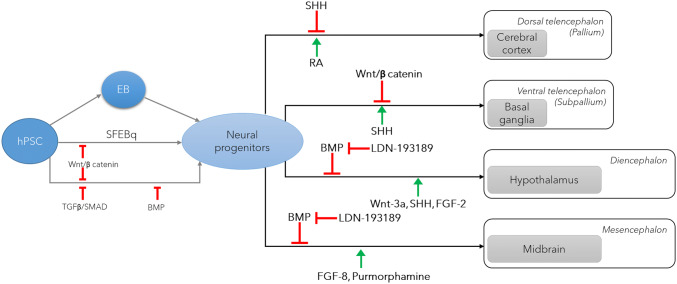

Pre-patterned brain-region specific organoid

In contrast to self-patterning method, pre-patterned method uses growth factors or small molecules to direct differentiations into specific brain regions such as the cerebral cortex [16–21], hippocampus [20, 21] and midbrain [22] (Fig. 2). The Sasai lab developed a serum free floating culture of EB-like aggregation with quick reaggregation (EFEBq) method. In the protocol, without Matrigel embedding, EB was induced to exhibit large domains of cortical neuroepithelium and spontaneously develop VZ, cortical plate, and marginal zone by adding Wnt and SMAD inhibition [16, 18]. This protocol has been improved by many research groups to produce brain-region specific organoids, but SMAD inhibition and lack of Matrigel embedding were mostly maintained. In 2015, Paşca et al., reported the advanced protocol to produce cortical organoids which contain neurons from both deep and superficial cortical layers and map transcriptionally to in vivo fetal development [19]. To achieve rapid and efficient neural induction, BMP and TGF-β signaling pathways were inhibited using dorsomorphin. The cortical organoids contain neurons that are electrophysiologically mature, display spontaneous activity, are surrounded by nonreactive astrocytes and form functional synapses [19]. In order to generate the midbrain organoids, Jo et al. successfully patterned the EB toward a mesencephalic fate upon addition of sonic hedgehog (SHH) and FGF8 followed by dual-SMAD inhibitor treatment (Noggin and SB431542). The 3D midbrain-like organoids exhibited midbrain neuron networks forming functional synapses and producing neuromelanin pigment and dopamine [22]. Along the same line as the midbrain, Sacaguchi et al. [21] generated the self-organizing dorsomedial telencephalic tissue with functional hippocampal granule- and pyramidal-like neurons by directing the EB using Wnt3a and SHH. In contrast the other pre-patterning method, Qian et al. [21] suggested embedding of EB in Matrigel only at early stage after dual SMAD inhibition to support the neuroepithelim induction which resulted in more discrete oSVZ zone, distinguishable layer-like neuron arrangements in cortical plate cytoarchitecture. Furthermore, the same group developed a miniaturized multi-well spinning bioreactor SpinΩ from 3D-printed parts and commercially available hardware to maintain the brain-region specific organoids longer time [21].

Fig. 2.

The key factors for establishing brain-region specific organoids. IZ intermediate zone, TGF-β transforming growth factor-β, SHH sonic hedgehog, RA retinoic acid, BMP bone morphogenic protein, SFEBq efficient serum-free culture of embryoid body-like aggregates

Through the guided differentiation, these organoids exhibit less variation in cell batches and better consistency in proportion of cell types. However, if the treatments of extrinsic factors are not well controlled, they sometimes show less defined cytoarchitecture because of the interference of self-organization [17]. For these organoids, extrinsic patterning factors are deprived or minimized after completion of patterning during the early stage of differentiation, followed by maturation with intrinsic patterning.

Assembloid

Human brain has highly arranged structure, whereas, brain organoids generally have heterogenous and unpredictable spatial organization and proportion. It is one of the major drawbacks of brain organoid model. To overcome this problem, several research groups suggested new approaches to assemble the brain region in controlled manner, known as assembloids. The hPSC are differentiated into different brain-region organoids first, and then they are combined together. In 2017, Birey et al. [23] reported a dorsal–ventral axis model by fusion of dorsal and ventral forebrain identities. Dorsal organoids and ventral organoids were produced embedded in Matrigel separately, and later co-embedded into one droplet of Matrigel [23, 24]. After combined, GABAergic cortical interneurons from the ventral domain migrated towards the dorsal domain making synapses with cortical glutamatergic neuron, resembling the tangential migration of interneurons from the subpallium to the cerebral cortex during late stages of development in vivo [23, 25]. In recent, Xiang et al. [26] showed the multi-region assembloid technology by fusing human thalamus-like brain organoids and cortical organoids. The assembloid platform recreated the reciprocal projections between thalamus and cortex [26]. This technique allows the understanding of human thalamic development and circuit organizations between two different brain regions.

The assembloid combining multiple lineage can be promising model to recapitulate the cellular complexity in central nervous system (CNS). Both self-patterned whole brain organoids and pre-patterned brain-region specific organoid are organized toward the ectodermal lineage which is restricted to production of neural cells. On the other hand, the multilineage brain assembloids can model the contribution of microglia, endothelial cell (EC) and pericyte during brain development and disease progress. Kierdorf et al. reviewed several main functions of microglia during brain development such as phagocytosis of apoptotic neurons [27, 28], trophic support of developing neurons [29], guidance of the developing vasculature and maturation [30] and refinement of neural circuits by synaptic pruning [31]. Moreover, microglia cerebral colonization influences the formation of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) during embryogenesis [32]. The contribution of EC and pericyte in maturation and functionality of brain organoid will be reviewed in detail in Sect. 4. To generate the multilineage assembloids, a comprehensive understanding of the programs driving brain development is required and the culture conditions to support multicellular state needs to be clarified. Types and features of brain organoids are summarized in Table 1 [11, 18, 20–24, 26].

Table 1.

Types and features of brain organoids

| Organoid type | Timing (days) | Cell source | Reproduced brain region (markers) | Laminar neuronal zone* | Notable features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-brain organoid | ~75 | hiPSC and siRNA (to model CDK5RAP2-dependent pathogenesis of microcephaly) |

Forebrain (FOXG1, SIX3), Hindbrain (KROX20, ISL1), Dorsal cortex (EMX1), Prefrontal cortex (AUTS2), Hippocampus (NRP2, FZD9, PROX1), Ventral forebrain (NKX2-1), Choroid plexus (TTR) |

oSVZ- and IFL-like layers oRGs (SOX2+, p-Vimentin+) |

Display of discrete brain regions 3D human in vitro model for study of brain developmental disorder |

[11] |

| Forebrain organoid | ~112 | hESCs | Cerebral cortex (cortical neuroepithelium) |

VZ (PAX6+/SOX2+) SVZ (TBR2+) CP (CTIP2+) MZ (REELIN+, CaMKII-α+) SP (Calretinin+) |

Relatively clear cortical lamination by Mann–Whitney test New self-organizing aspects of human corticogenesis 40% Oxygen concentration for corticogenesis |

[18] |

| Forebrain organoid | ~84 | hiPSCs | Forebrain (PAX6, OTX2, FOXG1) |

VZ, PP (day 28) VZ, SVZ, CP, MZ (day 56) VZ, iSVZ, oSVZ, CP, MA (day 84) Formation of diverse neuronal subtypes of six cortical layers |

A miniaturized spinning bioreactor Increased homogeneity of early stage |

[20, 21] |

| Hypothalamus organoid | ~40 | Hypothalamus (early development: NKX2.1, NKX2.2, RAX1, SOX2, NESTIN, FOXA2 (day 8)/peptidergic neuronal marker; POMC, VIP, OXT, NPY/hypothalamic neuronal lineages: OTP (day 40)) | None | |||

| Midbrain organoid | ~75 | Midbrain (TH + DA neuron (day 38)/FOXA2+, DAT (day 56)/NURR1+, PITX3+ (day 75)) | None | |||

| Midbrain organoid | ~122 | hESCs | Midbrain (mDA nascent stage: FOXA2, OTX2, CORIN, LMX1A (day 7)/post-mitotic mature neurons: MAP2+ > Ki67+ (day 35)/midbrain progenitors (apical surface): MASH1, OTX2) |

VZ IZ MZ |

Neuromelanin-like granules Laminar structure in the hMLOs (human Midbrain-like organoids) Obital shaker |

[22] |

| Assembloid | – | hESC and hiPSCs |

Cortical domain, Subpallium |

– |

Migration from subpallium spheroid (hSS) to cortical spheroid (hCS) Generation of Timothy syndrome patient-derived forebrain spheroid |

[24] |

| Assembloid | ~80 | hiPSCs | Cerebral cortex (Dorsal (TBR1+) and Ventral (NKX2-1+)) | VZ | Neuronal migratory dynamics in fused cerebral organoids | [23] |

| Assembloid | hCOs : day 18~, hMGEOs : day 18~, hThOs : day 16~, hThCOs : ~32 days post-fusion (dpf) |

hESCs (hMGEOs, hThOs) hiPSCs (hCOs) |

Cortical domain (MAP2, PAX6, VGLUT1, TBR1), Medial ganglionic eminence of subpallium (MAP2, NKL2-1, DLX2), Thalamic domain (MAP2, PAX6, TCF7L2, DBX1, GBX2) |

VZ/SVZ-like region (Thalamocortical (TC) and Corticothalamic (CT)) Both hMGEOs and hCOs: VZ (NKX2-1) Change of the thickness of VZ-like area (SOX2) during further development SVZ-like area (IP (TBR2), oRGs (FAM107A)) |

Axon connections between the thalamus and cortex in a 3D in vitro system (TC and CT axon projections), Functional maturation of Thalamic Neurons (intrinsic properties, the improved firing frequency in thlamic neurons from hThCOs) Interneuron migration from hMGEOs Functionally integration between hMGEOs and hCOs (by confirming calcium oscillations) |

[26] |

*hMGEO human medial ganglionic eminence, hCO human cortical organoid, hThOs human thalamus-like brain organoid, hThCOs human fused thalamus-cortex organoids, CP cortical plate, IZ intermediate zone, MZ marginal zone, SP subplate, VZ ventricular zone, SVZ subventricular zone, oSVZ outer SVZ, oRG outer radial glia

Disease modelling in human brain organoid

Neurodegenerative disorders

Currently, a variety of neurological disorders are modeled using brain organoid technology. Most of the neurodegenerative diseases including AD, PD, Huntington’s disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are partially or fully mediated by genetic factors. Since the first establishment of the iPSC, it became available to recapitulate the different pathological state depending on the individual’s genetic background. The pathologic feature of the AD are accumulation of amyloid-β plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [33]. Since 2D models do not offer the complex extracellular environments for extracellular protein aggregations, brain organoids are promising platform to study AD. To model the AD brain, brain organoids can be generated from iPSC from AD patients or mutated iPSC harboring amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, preseniin 1 (PSEN1), presenlin 2 (PSEN2) to model the familial AD, and Apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) for sporadic AD [34–36]. The first attempt in developing brain organoids from AD patient-derived iPSC having APP or PSEN1 mutation was accomplished by Raja et al. [34]. The pathological characteristics of AD such as amyloid aggregation, hyperphosphorylated tau protein, and endosome abnormalities were observed in the brain organoid [34]. Seo et al. [35] created the cerebral organoids from frontotemporal dementia patient-derived iPSCs carrying the Tau P301L mutation, and studied the molecular mechanism of tau-mediated pathology. Both of studies showed the progress of AD in brain organoids but immaturity of organoid and the absence of microglia important for neuroinflammation events are the critical limitations. Apart from AD, PD was also modeled in midbrain organoids showing the major pathologies including decreased neurite outgrowth and α-synuclein accumulation, suggesting that brain organoids are valuable for modeling age-related diseases [22, 37, 38]. Also, HD pathologies in early neurodevelopment were studied using cortical organoids generated using HD-derived induced iPSC [39]. ALS was modeled using iPSC in neuron spheroid mimicking the 3D brain organoid method [40], however, this model is not strictly categorized in whole brain or region-specific brain organoids. In order to study the molecular events priming the development of pathology during age neurodegenerative disease in brain organoids, further development of the methodologies for long-term maintenance and maturation of the brain organoids is highly required.

Neurodevelopmental disorder

Brain organoids are promising platform to explore the pathological mechanism of neurodevelopmental disorder. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complicated developmental disorder marked by social skills and communication deficits [41]. To study the hypothesis about excitatory/inhibitory imbalance in the autism brain, Mariani et al. [41] generated the cerebral organoids by using ASD-derived induced iPSC. The ASD organoid showed the abnormal proliferation of neural progenitor cells and increase of inhibitory GABAergic neurons successfully supporting the hypothesis [41]. Wang and coworkers moved forward to develop ASD organoids using genetically edited iPSCs harboring ASD causative gene mutation and study pathological effects of the gene in brain developments [42]. Recently, modeling of Zika virus (ZIKV) exposure to early brain has been in the limelight due to rapid spread of the virus through the America [43]. It causes serious damage to the developing fetal brain when infection occurs during pregnancy. Human cerebral organoids became useful model to observe the brain developmental disorders by ZIKV infection [21, 44–47]. ZIKV-induced brain pathology was repeated in human cerebral organoid platform including increase of cell death and reduced proliferation which is similar to microcephaly [21, 44, 45]. Yoon et al. [46] unveiled the ZIKV–host interactions showing the reduction of radial glial cell proliferation and cause adherent junction complex deficits by introduction of ZIKV–NS2A protein encoded by ZIKV to human forebrain organoid. Those findings represent an inflection point for the discovery of effective approaches to prevent or cure neurodevelopmental diseases.

Vascularization of brain organoids

Even though brain organoids possess many advantages over previous cell models, they are not identical replicas of their in vivo counterpart. One of the major drawbacks of current methodologies is the absence of the functional brain vasculature in the brain organoid. The blood vessel in the brain, known as BBB, has unique properties and cellular composition distinctive to peripheral blood vessel. The BBB serve as a physical, functional and immunological boundary between neural tissue and circulating blood to protect the brain [48]. Communication between the nervous system and the neurovascular system is important for proper formation and function of the CNS during pre-natal development [49]. For example, the periventricular blood vessels selectively influence the neocortical interneuron progenitor behavior and neurogenesis during development [50]. Recent studies also found that the angiogenesis timing of the CNS of the mouse embryo is orchestrated by compartment-specific factor in the forebrain [49], hindbrain [51, 52] and spinal cord [53]. The absence of blood vessel in brain organoid implies the incomplete cellular communications during differentiation and limitation in organoid kept fully alive over a prolonged period, which highly restricts the maturation of neuronal function, cellular diversities, and complex networks [54]. Neurons in mature organoids have the ability to fire trains of action potentials in response to positive current injection and show robust spontaneous excitatory/inhibitory postsynaptic currents [19]. In vivo maturation, by implantation into a mouse, has been demonstrated to enhance the maturity of many types of hPSC-derived organoids by allowing the use of host vascular system. Brain organoids implanted into the mouse brain had better neuronal maturation [55], proving that vascularization is a key to generate the adult-like brain organoid. The vascularization of brain organoid is important not only for normal brain function, but also for neurological disease modeling. For example, BBB is an infection route of ZIKV [56] and the cascade of molecular events after infection ends in abnormal and leaky vasculature [57]. Also, brain vasculature disorder is considered as a key factor contributing the onset and progression of AD. Brain organoids, however, cannot to fully represent the stories of ZIKV infection [21, 44, 45] nor AD pathological features [34, 35] without vasculature. Here we will introduce four approaches used for brain organoid vascularization and discuss about the advantages and limitations of each technology (Fig. 2).

In vivo vascularization of brain organoids

Mansour et al. suggested the in vivo maturation approach for brain organoids vascularization by transplanting the organoids onto vascular bed in the cortex of the adult mice [55]. The host vasculature was incorporated to the brain organoids within 2 weeks and the formation of germinal zones, glia and neurons was successfully identified [55]. Active blood flow through the host derived vessels has been confirmed inside the brain using two-photon microscope after infusing the grafted mice with dextran dye. This method enabled the brain organoids to undergo less necrosis, showing extensive neuronal process, healthy synapses and synchronized and correlated maturation of neuronal firing by for mimicking the angiogenesis occurring in normal development of brain neuronal cells [55]. Despite the many advantages of in vivo maturation of brain organoids, microvessel originated from host animal limits the generation of fully humanized brain model.

Integration with EC

Pham et al., suggested to mimic the developmental perineural vascular plexus by integrating brain organoids with endothelial cells for vascularization [58]. Simultaneously, whole-brain organoids and endothelial cells (ECs) were generated from iPSC from same patient, and brain organoids were re-embedded on the Matrigel with differentiated ECs. This method allowed the vascularization from the surrounding matrix as opposed to direct injection into the center of organoids [58]. They showed the robust penetration of our layer of organoids but only some ingrowth of blood vessel into core of the organoids [58]. After transplantation in NSG mouse, blood vessel has penetrated the center of a rosette inside the organoids, however, the connectivity of organoid capillaries with in vivo host brain was not proved [58]. Distinct from in vivo maturation method (4.1), this study implies the possibility of developing all humanized vascularized brain organoid harboring same genetic background (Fig. 3) [14].

Fig. 3.

Enhancement of brain organoid technology by combining with neurovascular unit

Genetic engineering of human brain organoids

In fact, it is a quite challenging to generate non-neural cell types within the brain organoid without harming the heterogeneity because patterning is always trade-off between diversity and consistency. In order to induce the vascular-like structure in the cortical organoid, the fate of hPSCs was reprogrammed to get developed to endothelial cells [59]. For this, transcription factor ETV2, a master regulator for vascular endothelial cell development was introduced to hPSCs and mixed with native hPSCs when forming EBs [59]. The highest expression of ETV2 was achieved at day 18 and the vasculogenesis factors such as FLT1, HAND1, MME and VTN were successfully detected in cortical organoid when ETV2-expressing lentivirus-infected hPSCs were 20% of total hPSCs [59]. The vascularized human cortical organoids (vhCOs) have shown tight junction marker ZO1, and physical barrier function the organoids was determined using trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) analysis [59]. Furthermore, vhCOs formed functional blood vessel in vivo after implanted at mouse limbs, while hCOs showed the very limited vascular connection with host mouse [59]. The finding implies the need for brain organoid vascularization for the application in tissue regeneration. Limitation of the vhCOs is that BBB functionality in vhCOs may incomplete because of the absence of pericyte. The brain pericytes regulate the vital functions of the neurovascular unit by controlling the vascular flow and regulation of physical barrier function. Even though, pericyte transcription factors have not been well defined yet, direct differentiation of hPSCs to brain pericyte can be a potential approach for the generation of fully functional BBB in the brain organoid.

Brain organoid-on-a-chip

In recent years, the shortcomings of conventional cell culture platform have led to the emergence of Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC). OoC is based on the technological advances in microfluidics and tissue engineering which enables the design of customized tissue microenvironment by accurate control of fluidic, mechanical, chemical, and structural cues. It facilitate recreating dynamic interplay between multiple types of cells, controlled in separate microchannels, and extracellular matrix (ECM)-cell interactions exhibiting hall marks of native tissues [60–62]. In addition, OoC technology provides a vascular-like microfluidic perfusion which may overcome the poor supply of oxygen and nutrients in brain organoids. In recent, there have been several attempts to merge organoids and OoC to successfully recapitulate the complex 3D architecture of the organ. Homan et al. [63] showed flow-enhanced vascularization and maturation of kidney organoids by controlling the speed of fluids using microfluidic devices. Interestingly, vascularized kidney organoids cultured under high flow had more mature podocyte and tubular compartments with enhanced cellular polarity and adult gene expression [63]. It clearly implies potential of OoC for maturation of organoids. The use of OoC will be more powerful with strategies for brain organoid vascularization including gene engineering and integration of EC.

In order to study the mechanism of human brain wrinkling during development, Karzburn et al. [64] built a microfluidic device, which allows nutrient exchange by diffusion and in situ whole organ imaging of brain organoids. The microfluidic device had two microchannels; brain organoid and media supply channels separated by porous membrane. Brain organoid was generated from hESC aggregate in the 150 µm microchannel (brain organoid channel) filled with Matrigel, and fresh media was continuously flown through the opposite channel (media supply channel) utilizing microfluidic perfusion. Although vascular networks were not recreated, the media supply channel could serve as an artificial capillary providing efficient exchange of nutrient and gas. Using the on-chip organoids, they successfully demonstrated the brain wrinkling is driven by a mechanical instability, suggesting that OoC enables brain organoid maturation and serve as a promising tool to study the physics and biology of early human brain development.

Wang et al. developed the brain organoid-on-a- chip with multiple perfusion channels to study the effect of prenatal nicotine exposure on early brain development. Distinct from microdevice used in [64], the nutrient is supplied through the perfusion channel without porous membrane and metabolic waste from brain organoid is excreted to neighboring microchannel [65]. Brain organoids differentiated from hiPSCs with perfusion showed the increase of cell viability and expression of CD133 at the apical surface of the ventricular zone, and cortical layer markers, TBR1 and CT1P2 compared to traditional 2D culture [65]. In this model, they found that nicotine exposure has adverse effects on the early stage of brain, such as disrupted brain regional organization, abnormal cortical development, and premature neuronal differentiation. The OoC appears fairly promising to meet the need of microenvironmental control of organoid culture to offer the physiologically relevant brain development. There are still some limitations of current OoC platform in accurate recreation of brain physiology. The perfusion partially provides a functional mimicry of brain microvessel, however, it is far from biological selective barrier function of BBB. Polydimethylsiloxane, a polymer widely used for the microfabrication, absorbs the small molecules which results in imprecise analysis of drug responses. Incorporation of human brain endothelial [48, 66] in microchannel of OoC and the use of advanced material for microfabrication [67] will improve mimicry of the brain organoids.

Future perspectives

There is a long way to go before we can use brain organoids for brain neural tissue regeneration. However, brain organoids capable of recapitulating the human physiological responses can serve as an extraordinary platform for development of neurotherapeutics, disease modeling, precision medicine for brain regeneration. To move forward the clinical applications, brain organoid technology needs tremedous advances to overcome the current limitation. In this review, we focused on discussing current bioengineering technologies for brain organoid vascularization to enhance the maturation and supply of oxygen and nutrients. Apart from vascular endothelial cells, other types of non-neural cells including microglia, oligodendrocytes, and meningeal cells also need to be considered to emulate the complex physiological activity in brain. Interesting, microglia was found to be innately developed within cerebral organoids due to lack of dual-SMAD inhibition during organoid generation [68]. This study implies the importance of balancing intrinsic and extrinsic patterning for physiologically relevant brain model. However, it is still not possible to control the consistent distribution of non-neural type cells in brain organoids. Genetic engineering of hPSCs to generate the diverse types of cells in organoid and the use of organ-on-a-chip technology which enables controlling the individual culture condition depending on the cell type will be promising approach to overcome the limitation. The use of animal-derived ECM is not suitable for human and its ECM composition differs from brain ECM. The development of safe, defined, and brain friendly ECM alternatives to Matrigel will accelerate the clinical application of brain organoids.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (Korea, government, Ministry of Science and ICT; NRF-2019R1F1A1059034 and Research Fund (1.170098.01) of UNIST (Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests.

Ethical statement

There are no animal experiments carried out for this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hodge RD, Bakken TE, Miller JA, Smith KA, Barkan ER, Graybuck LT, et al. Conserved cell types with divergent features in human versus mouse cortex. Nature. 2019;573:61–68. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1506-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelava I, Lancaster MA. Dishing out mini-brains: current progress and future prospects in brain organoid research. Dev Biol. 2016;420:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondo T, Asai M, Tsukita K, Kutoku Y, Ohsawa Y, Sunada Y, et al. Modeling Alzheimer’s disease with iPSCs reveals stress phenotypes associated with intracellular Aβ and differential drug responsiveness. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schöndorf DC, Aureli M, McAllister FE, Hindley CJ, Mayer F, Schmid B, et al. iPSC-derived neurons from GBA1-associated Parkinson’s disease patients show autophagic defects and impaired calcium homeostasis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4028. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russo FB, Brito A, de Freitas AM, Castanha A, de Freitas BC, Beltrão-Braga PCB. The use of iPSC technology for modeling Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;130:104483. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Miki Y, Ono K, Hata S, Suzuki T, Kumamoto H, Sasano H. The advantages of co-culture over mono cell culture in simulating in vivo environment. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;131:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oksdath M, Perrin SL, Bardy C, Hilder EF, DeForest CA, Arrua RD, et al. Synthetic scaffolds to control the biochemical, mechanical, and geometrical environment of stem cell-derived brain organoids. APL Bioeng. 2018;2:041501. doi: 10.1063/1.5045124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen JB, Parmar M. Strengths and limitations of the neurosphere culture system. Mol Neurobiol. 2006;34:153–161. doi: 10.1385/MN:34:3:153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pluchino S, Zanotti L, Rossi B, Brambilla E, Ottoboni L, Salani G, et al. Neurosphere-derived multipotent precursors promote neuroprotection by an immunomodulatory mechanism. Nature. 2005;436:266–71. doi: 10.1038/nature03889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lancaster MA, Renner M, Martin CA, Wenzel D, Bicknell LS, Hurles ME, et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature. 2013;501:373–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA. Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:2329–40. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelava I, Lancaster MA. Stem cell models of human brain development. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:736–748. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qian X, Song H, Ming GL. Brain organoids: advances, applications and challenges. Development. 2019;146:dev166074. doi: 10.1242/dev.166074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt–villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eiraku M, Takata N, Ishibashi H, Kawada M, Sakakura E, Okuda S, et al. Self-organizing optic-cup morphogenesis in three-dimensional culture. Nature. 2011;472:51–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lancaster MA, Corsini NS, Wolfinger S, Gustafson EH, Phillips AW, Burkard TR, et al. Guided self-organization and cortical plate formation in human brain organoids. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:659–66. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadoshima T, Sakaguchi H, Nakano T, Soen M, Ando S, Eiraku M, et al. Self-organization of axial polarity, inside-out layer pattern, and species-specific progenitor dynamics in human ES cell-derived neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20284–20289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315710110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paşca AM, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, Tian Y, Makinson CD, Huber N, et al. Functional cortical neurons and astrocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in 3D culture. Nat Methods. 2015;12:671–678. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qian X, Jacob F, Song MM, Nguyen HN, Song H, Ming GL. Generation of human brain region-specific organoids using a miniaturized spinning bioreactor. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:565–80. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian X, Nguyen HN, Song MM, Hadiono C, Ogden SC, Hammack C, et al. Brain-region-specific organoids using mini-bioreactors for modeling ZIKV exposure. Cell. 2016;165:1238–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jo J, Xiao Y, Sun AX, Cukuroglu E, Tran HD, Göke J, et al. Midbrain-like organoids from human pluripotent stem cells contain functional dopaminergic and neuromelanin-producing neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bagley JA, Reumann D, Bian S, Lévi-Strauss J, Knoblich JA. Fused cerebral organoids model interactions between brain regions. Nat Methods. 2017;14:743–51. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birey F, Andersen J, Makinson CD, Islam S, Wei W, Huber N, et al. Assembly of functionally integrated human forebrain spheroids. Nature. 2017;545:54–9. doi: 10.1038/nature22330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renner M, Lancaster MA, Bian S, Choi H, Ku T, Peer A, et al. Self-organized developmental patterning and differentiation in cerebral organoids. EMBO J. 2017;36:1316–1329. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiang Y, Tanaka Y, Cakir B, Patterson B, Kim KY, Sun P, et al. hESC-derived thalamic organoids form reciprocal projections when fused with cortical organoids. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24:487–97.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi K, Prinz M, Stagi M, Chechneva O, Neumann H. TREM2-transduced myeloid precursors mediate nervous tissue debris clearance and facilitate recovery in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi K, Rochford CD, Neumann H. Clearance of apoptotic neurons without inflammation by microglial triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2. J Exp Med. 2005;201:647–657. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueno M, Fujita Y, Tanaka T, Nakamura Y, Kikuta J, Ishii M, et al. Layer V cortical neurons require microglial support for survival during postnatal development. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:543–51. doi: 10.1038/nn.3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fantin A, Vieira JM, Gestri G, Denti L, Schwarz Q, Prykhozhij S, et al. Tissue macrophages act as cellular chaperones for vascular anastomosis downstream of VEGF-mediated endothelial tip cell induction. Blood. 2010;116:829–840. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paolicelli RC, Bolasco G, Pagani F, Maggi L, Scianni M, Panzanelli P, et al. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science. 2011;333:1456–1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kierdorf K, Prinz M. Microglia in steady state. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3201–3209. doi: 10.1172/JCI90602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JY, Kim HS. Extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative diseases: a double-edged sword. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;14:667–678. doi: 10.1007/s13770-017-0090-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raja WK, Mungenast AE, Lin YT, Ko T, Abdurrob F, Seo J, et al. Self-organizing 3D human neural tissue derived from induced pluripotent stem cells recapitulate Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seo J, Kritskiy O, Watson LA, Barker SJ, Dey D, Raja WK, et al. Inhibition of p25/Cdk5 attenuates tauopathy in mouse and iPSC models of frontotemporal dementia. J Neurosci. 2017;37:9917–9924. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0621-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan Y, Song L, Bejoy J, Zhao J, Kanekiyo T, Bu G, et al. Modeling neurodegenerative microenvironment using cortical organoids derived from human stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2018;24:1125–1137. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2017.0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monzel AS, Smits LM, Hemmer K, Hachi S, Moreno EL, van Wuellen T, et al. Derivation of human midbrain-specific organoids from neuroepithelial stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8:1144–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smits LM, Reinhardt L, Reinhardt P, Glatza M, Monzel AS, Stanslowsky N, et al. Modeling Parkinson’s disease in midbrain-like organoids. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2019;5:5. doi: 10.1038/s41531-019-0078-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conforti P, Besusso D, Bocchi VD, Faedo A, Cesana E, Rossetti G, et al. Faulty neuronal determination and cell polarization are reverted by modulating HD early phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E762–E771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715865115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawada J, Kaneda S, Kirihara T, Maroof A, Levi T, Eggan K, et al. Generation of a motor nerve organoid with human stem cell-derived neurons. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:1441–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mariani J, Coppola G, Zhang P, Abyzov A, Provini L, Tomasini L, et al. FOXG1-dependent dysregulation of GABA/glutamate neuron differentiation in autism spectrum disorders. Cell. 2015;162:375–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang P, Mokhtari R, Pedrosa E, Kirschenbaum M, Bayrak C, Zheng D, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated heterozygous knockout of the autism gene CHD8 and characterization of its transcriptional networks in cerebral organoids derived from iPS cells. Mol Autism. 2017;8:11. doi: 10.1186/s13229-017-0124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong SS, Poon RW, Wong SC. Zika virus infection-the next wave after dengue? J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:226–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcez PP, Loiola EC, Madeiro da Costa R, Higa LM, Trindade P, Delvecchio R, et al. Zika virus impairs growth in human neurospheres and brain organoids. Science. 2016;352:816–818. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cugola FR, Fernandes IR, Russo FB, Freitas BC, Dias JL, Guimarães KP, et al. The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature. 2016;534:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nature18296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoon KJ, Song G, Qian X, Pan J, Xu D, Rho HS, et al. Zika-virus-encoded NS2A disrupts mammalian cortical neurogenesis by degrading adherens junction proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JK, Shin OS. Advances in Zika virus–host cell interaction: current knowledge and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:E1101. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park TE, Mustafaoglu N, Herland A, Hasselkus R, Mannix R, FitzGerald EA, et al. Hypoxia-enhanced Blood-Brain Barrier Chip recapitulates human barrier function and shuttling of drugs and antibodies. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2621. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10588-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vasudevan A, Long JE, Crandall JE, Rubenstein JL, Bhide PG. Compartment-specific transcription factors orchestrate angiogenesis gradients in the embryonic brain. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:429–39. doi: 10.1038/nn2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan X, Liu WA, Zhang XJ, Shi W, Ren SQ, Li Z, et al. Vascular influence on ventral telencephalic progenitors and neocortical interneuron production. Dev Cell. 2016;36:624–638. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tata M, Wall I, Joyce A, Vieira JM, Kessaris N, Ruhrberg C. Regulation of embryonic neurogenesis by germinal zone vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:13414–13419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613113113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ulrich F, Ma LH, Baker RG, Torres-Vázquez J. Neurovascular development in the embryonic zebrafish hindbrain. Dev Biol. 2011;357:134–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Himmels P, Paredes I, Adler H, Karakatsani A, Luck R, Marti HH, et al. Motor neurons control blood vessel patterning in the developing spinal cord. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14583. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McMurtrey RJ. Analytic models of oxygen and nutrient diffusion, metabolism dynamics, and architecture optimization in three-dimensional tissue constructs with applications and insights in cerebral organoids. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2016;22:221–249. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2015.0375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mansour AA, Gonçalves JT, Bloyd CW, Li H, Fernandes S, Quang D, et al. An in vivo model of functional and vascularized human brain organoids. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:432–441. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alimonti JB, Ribecco-Lutkiewicz M, Sodja C, Jezierski A, Stanimirovic DB, Liu Q, et al. Zika virus crosses an in vitro human blood brain barrier model. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2018;15:15. doi: 10.1186/s12987-018-0100-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shao Q, Herrlinger S, Yang SL, Lai F, Moore JM, Brindley MA, et al. Zika virus infection disrupts neurovascular development and results in postnatal microcephaly with brain damage. Development. 2016;143:4127–4136. doi: 10.1242/dev.143768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pham MT, Pollock KM, Rose MD, Cary WA, Stewart HR, Zhou P, et al. Generation of human vascularized brain organoids. Neuroreport. 2018;29:588–593. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cakir B, Xiang Y, Tanaka Y, Kural MH, Parent M, Kang YJ, et al. Engineering of human brain organoids with a functional vascular-like system. Nat Methods. 2019;16:1169–1175. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0586-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peyrin JM, Deleglise B, Saias L, Vignes M, Gougis P, Magnifico S, et al. Axon diodes for the reconstruction of oriented neuronal networks in microfluidic chambers. Lab Chip. 2011;11:3663–3673. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20014c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li X, Valadez AV, Zuo P, Nie Z. Microfluidic 3D cell culture: potential application for tissue-based bioassays. Bioanalysis. 2012;4:1509–1525. doi: 10.4155/bio.12.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Z, Samanipour R, Koo K, Kim K. Organ-on-a-chip platforms for drug delivery and cell characterization: a review. Sens Mater. 2015;27:487–506. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Homan KA, Gupta N, Kroll KT, Kolesky DB, Skylar-Scott M, Miyoshi T, et al. Flow-enhanced vascularization and maturation of kidney organoids in vitro. Nat Methods. 2019;16:255–262. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0325-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karzbrun E, Kshirsagar A, Cohen SR, Hanna JH, Reiner O. Human brain organoids on a chip reveal the physics of folding. Nat Phys. 2018;14:515–22. doi: 10.1038/s41567-018-0046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y, Wang H, Deng P, Chen W, Guo Y, Tao T, et al. In situ differentiation and generation of functional liver organoids from human iPSCs in a 3D perfusable chip system. Lab Chip. 2018;18:3606–3616. doi: 10.1039/c8lc00869h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Herland A, van der Meer AD, FitzGerald EA, Park TE, Sleeboom JJ, Ingber DE. Distinct contributions of astrocytes and pericytes to neuroinflammation identified in a 3D human blood-brain barrier on a chip. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nguyen T, Jung SH, Lee MS, Park TE, Ahn SK, Kang JH. Robust chemical bonding of PMMA microfluidic devices to porous PETE membranes for reliable cytotoxicity testing of drugs. Lab Chip. 2019;19:3706–3713. doi: 10.1039/c9lc00338j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ormel PR, de Sá Vieira R, van Bodegraven EJ, Karst H, Harschnitz O, Sneeboer MAM, et al. Microglia innately develop within cerebral organoids. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4167–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06684-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]