Abstract

A 42 year-old patient presented with circulatory failure and lactic acidosis. Clinical features, later coupled with biological tests, led to the diagnosis of wet beriberi syndrome and scurvy. Echocardiography showed a pattern of thiamine deficiency with high cardiac output and low vascular resistance. The patient's condition and biological parameters immediately improved after treatment injections of thiamine. Wet BeriBeri is often overlooked in western countries and is a diagnosis that must be considered based on history, and clinical and echocardiographical findings.

Résumé

Un patient âgé de 42 ans a présenté une insuffisance circulatoire et une acidose lactique. Ses caractéristiques cliniques et les résultats de laboratoire obtenus ultérieurement ont mené au diagnostic de béribéri humide et de scorbut. Une échocardiographie a révélé un profil indiquant une carence en thiamine accompagnée d’un débit cardiaque élevé et d’une faible résistance vasculaire. L’état et les paramètres biologiques du patient se sont améliorés immédiatement après l’administration de thiamine par injection. Le diagnostic de béribéri humide est souvent négligé dans les pays occidentaux, mais il faut en tenir compte en présence des signes appropriés : antécédents du patient, observations cliniques et résultats à l’échocardiographie.

Wet BeriBeri is a recognized etiology of high-output heart failure with lactic acidosis. It remains unusual in western countries and is a health hazard. We describe a case of thiamine deficiency associated with scurvy features exhibiting circulatory shock and discuss treatment and outcome.

Case

A 42-year-old Caucasian man presented to the emergency department with a 1-week history of chest pain and progressive dyspnea. On admission, he had minimal peripheral edema and circulatory failure features with low blood pressure of 90/50 mm Hg, tachypnea at 40 per minute, and tachycardia of 130 beats per minute. Capillary refill time was higher than 3 seconds. A grade 2/6 systolic ejection murmur was found, as well as bilateral pulmonary basal crackles. There was no fever, no ascites, or any stigmata of cirrhosis. Periodontal disease (with bleeding gums) and features of malnutrition (body mass index 19 kg/m2) were also observed. He admitted to chronic alcohol consumption of 20 g/day and a diet restricted to rapidly absorbed refined carbohydrates. Past medical history was otherwise unremarkable. He had no history of toxic ingestions, which was later confirmed with a toxicology screen.

Electrocardiogram showed regular sinus rhythm with a negative T wave in lead augmented vector left. Initial blood tests (Table 1) indicated high levels of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) (7527 ng/L), elevated troponin T (high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T [hs-cTnT]; 125 ng/L), and lactic acidosis (6.3 mmol/L). A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF 50%) with inferior hypokinesia and non-dilated left cavities (left ventricle diastolic diameter 55 mm; left atrial surface 18 cm2). The right-ventricle ejection fraction was also preserved with a tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion of 20 mm. Estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure was 50 mm Hg. A 2-mm pericardial effusion was found anterior to the right atrium and ventricle. Hemodynamic echographic profile assessement indicated high cardiac output at 9.1 L/min (indexed cardiac output of 4.9 L/min per m2), with velocity time integral at 22 cm and heart rate at 110 beats per minute. Systemic vascular resistance was very low at 465 dynes/sec per cm5. A computed tomography scan ruled out aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, any infectious process, and any cirrhosis feature. Additional laboratory investigations revealed normal thyroid hormone levels, no anemia, and normal serum inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein < 1 mg/L, procalcitonin < 0.5 mg/L), excluding sepsis (Table 1). At this point, wet beriberi was suspected.

Table 1.

Biological data at admission for a patient with circulatory shock due to wet beriberi and scurvy

| Test | Outcome | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| Natremia, mmol/L | 136 | 136-145 |

| Kalaemia, mmol/L | 4.2 | 3.4-4.5 |

| Chlorine, mmol/L | 104 | 98-107 |

| Bicarbonates, mmol/L | 19 | 22-29 |

| Protein, g/L | 62 | 64-83 |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 2.34 | 2.1-2.55 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 3.2 | 3.2-7.4 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 67 | 64-104 |

| Albumin, g/L | 27 | 35-52 |

| Prealbumin, g/L | 0.21 | 0.18-0.45 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | < 1.0 | < 5.0 |

| Troponin, ng/L | 125 | < 34 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 6.3 | 0.5-2.2 |

| Nt-pro-Brain natriuretic peptide, ng/L | 7527 | <125 |

| AST, U/L | 40 | 5-34 |

| ALT, U/L | 21 | < 55 |

| Gamma GT, U/L | 115 | 12-64 |

| TSH, mUI/L | 3.9 | 0.4-3.1 |

| T3L, pmol/L | 3.0 | 2.9-4.9 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 130 | 130-170 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GT, glutamyl transferase; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; T3L, triiodothyronine.

Coronary angiography performed on the second day was normal. Acute myocarditis was not suspected since LVEF was preserved with no alteration of cardiac output, and inflammatory markers were negative. Additional metanephrine and normetanephrine levels were in the normal range. Hypoalbuminemia (27 g/L) and iron deficiency were detected. A salivary gland biopsy, performed to rule out amyloidosis, was normal.

Beriberi was confirmed 2 days later with blood tests showing a low serum thiamine (B1) level of 44.7 nmol/L (normal range: 66-200 nmol/L). Scurvy was concomitantly clinically and biologically diagnosed (Vitamin C6 μmol/L; normal range: 25-85).

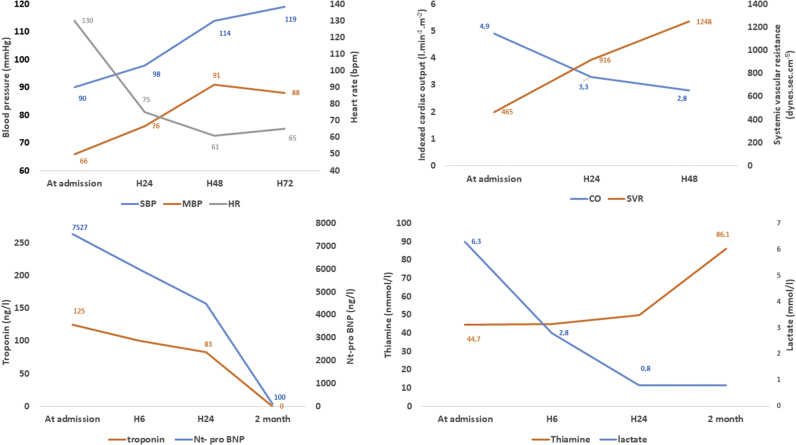

Treatment consisted of intravenous injections of 100 mg of thiamine twice a day followed by oral supplementation of 250 mg 3 times a day. β-Blocker therapy was also initially initiated. We observed a rapid improvement in biological and hemodynamic parameters (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Acute clinical evolution and biological findings kinetics, for a patient with circulatory shock due to wet beriberi and scurvy. Thiamine injections were started upon admission. bpm, beats per minute; CO, indexed cardiac output; H, hour; HR, heart rate: MBP, mean blood pressure; nt-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

During a 2-month follow-up period without the need for medication (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or diuretics), he showed no relapse. Thiamine blood level rose to 86.1 nmol/L, and NT-proBNP level normalized. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a preserved LVEF (68%) with normal global longitudinal strain—22.3%. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed, revealing no myocardial fibrosis or myocarditis-related scarring.

Discussion

Thiamine deficiency is an unusual cause of circulatory failure1 and remains a health hazard, especially due to malnutrition.2 Treatment with thiamine is safe and effective, highlighting the importance of suspecting the diagnosis early, particularly in an emergency situation. Its prevalence has never been evaluated in western countries, and the literature is limited to a few case reports. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published data describing thiamine concentration at clinical presentation. In a few case reports, blood levels were found not to be severely depressed.3,4 To highlight this finding, Martin et al.5 discussed that not all people are equally sensitive to thiamine deficiency, with consequences depending on genetic predisposition, alcoholic and chronic nutritional state, arguing for the existence of thiamine-using enzyme variants. The capacity for thiamine uptake into the cells may also play a role. However, to clarify these points, genetic studies would be required.

Beriberi is a well known etiology of high-output cardiac failure. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the observed hemodynamic abnormalities.6

Our case describes a patient with cardiogenic shock due to thiamine deficiency and scurvy. Right heart failure has been previously described in patients with scurvy,7 mainly as a result of severe pulmonary hypertension. Vitamin C has vasodilatory properties, increasing availability of endothelial nitric oxide.8 In our case, the data and the complete recovery after thiamine administration suggest the exclusive accountability of thiamine deficiency in the presentation. Diagnosing wet beriberi requires a high clinical level of suspicion based on medical history and physical examination. The only way to establish the diagnosis is to consider it, and monitor improvement after thiamine administration, as blood tests are not rapidly available (they take weeks to be processed).

Novel Teaching Points.

-

•

Thiamine deficiency is a well known, yet unfrequent cause of circulatory shock and lactic acidosis in western countries and remains a health hazard, especially as a result of malnutrition and alcohol consumption.

-

•

Wet beriberi must be considered based on history, and clinical and echocardiographical findings, without waiting for thiamine testing in patients with dietary decompensation.

-

•

A small drop in thiamine blood levels may be sufficient to explain lactic acidosis and hemodynamic instability.

-

•

Scurvy can occur in conjunction with wet beriberi in patients with altered nutritional status.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: The research reported has adhered to the relevant ethical guidelines.

See page 717 for disclosure information.

References

- 1.DiNicolantonio J.J., Liu J., O’Keefe J.H. Thiamine and cardiovascular disease: a literature review. Progr Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitfield K.C., Bourassa M.W., Adamolekun B. Thiamine deficiency disorders: diagnosis, prevalence, and a roadmap for global control programs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1430:3–43. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei Y., Zheng M.-H., Huang W., Zhang J., Lu Y. Wet beriberi with multiple organ failure remarkably reversed by thiamine administration: a case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasaki T., Yukizane T., Atsuta H. [A case of thiamine deficiency with psychotic symptoms—blood concentration of thiamine and response to therapy] Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2010;112:97–110. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin P.R., Singleton C.K., Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:134–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attas M., Hanley H.G., Stultz D., Jones M.R., McAllister R.G. Fulminant beriberi heart disease with lactic acidosis: presentation of a case with evaluation of left ventricular function and review of pathophysiologic mechanisms. Circulation. 1978;58:566–572. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbas F., Ha L.D., Sterns R., Von Doenhoff L. Reversible right heart failure in scurvy rediscovery of an old observation. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taddei S., Virdis A., Ghiadoni L., Magagna A., Salvetti A. Vitamin C improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation by restoring nitric oxide activity in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;97:2222–2229. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.22.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]