Abstract

Objective

The objective of the present study was to explore causal pathways to understand how second traumatic experiences could affect the development of emotional exhaustion and psychiatric problems.

Methods

A total of 582 workers who had jobs vulnerable to secondary traumatic experiences were enrolled for this study. Emotional exhaustion, secondary trauma, resilience, perceived stress, depression, anxiety, and sleep problems were evaluated. A model with pathways from secondary traumatic experience score to depression and anxiety was proposed. The participants were divided into three groups according to the resilience: the low, middle and high resilience group.

Results

Resilience was a meaningful moderator between secondary traumatic experiences and psychiatric problems. In the path model, the secondary trauma and perceived stress directly and indirectly predicted perceived stress, emotional exhaustion, depression, anxiety, and sleep problems in all three groups. Direct effects of perceived stress on depression and anxiety were the largest in the low resilience group. However, direct effects of secondary trauma on perceived stress and emotional exhaustion were the largest in the high resilience group.

Conclusion

Understanding the needs of focusing for distinct psychological factors offers a valuable direction for the development of intervention programs to prevent emotional exhaustion among workers with secondary traumatic experiences.

Keywords: Workers, Secondary traumatic experiences, Emotional exhaustion, Associated factors, Path analysis

INTRODUCTION

Secondary traumatic stress has been defined as a natural and consequential behavior and emotion resulting from knowing about the traumatizing event experienced by a significant other and the stress resulting from helping or wanting to help a traumatized or suffering person [1]. A great deal of social work practice addresses client’s crisis situations or helps clients deal with trauma that occurs in the aftermath of crisis [2]. Providing trauma-intervention services places these workers at risk for traumatic responses themselves [3].

Previous studies have used various synonyms of secondary traumatic stress such as burnout [4]. It is best defined as a syndrome having symptoms of secondary traumatic stress and professional burnout [1,2,5,6]. Professional burnout has been defined as a psychological state resulting from prolonged emotional or psychological stress on the job [7]. Burnout could be defined as a psychological state resulting from emotional stress. The emotional exhaustion is a chronic state of physical and emotional depletion that results from excessive job and/or personal demands and continuous stress [8]. Moreover, secondary traumatic experiences caused by repetitive demands for compassion could affect emotional exhaustion [9]. Like secondary traumatic stress, reactions to burnout include emotional responses such as emotional exhaustion [10], depression, and anxiety [4].

Emotional exhaustion is considered to have a high predictive value in anticipating the impact of stress on health in an active work population [7]. Workers such as nurses, social workers, firefighters and police officers who have a job that is vulnerable to secondary traumatic experiences can also easily experience stress [2,11-14]. Additionally, various studies have determined the relationship between depression and burnout [15]. Although whether depression can be considered as a result of burnout or the opposite remains unclear and overlapping symptoms between twos have not been clearly solved yet either [15], the previous studies has found that burnout can develop into depression under certain conditions [16-18]. Unfortunately, the vast majority of studies investigating this relationship is of cross-sectional design; however, on the basis of results of previous studies, the causal models including secondary traumatic experiences, stresses, emotional exhaustion and symptoms of depression could be speculated. The secondary traumatic experiences could increase perceived stresses and stresses might affect emotional exhaustion of health professionals. Additionally, increased emotional exhaustion could affect the development of symptoms of depression.

Meanwhile, recent studies have shown a link between resilience and emotional exhaustion [19,20]. Resilience appears to be protective against emotional exhaustion [21]. Resilience is negatively associated with post-traumatic and depressive symptoms [22]. Additionally, resilience can moderate the relationship between subjective experience about traumatic experiences and depressive symptoms [22].

Despite above expected correlations between secondary traumatic experience-related factors and clinical importance, pathways to the development of psychiatric problems from secondary trauma have not been reported yet. By clarifying such pathways, the development of psychiatric problems from emotional exhaustion and perceived stress in workers with secondary traumatic experiences could be prevented.

Thus, the objective of the present study was to explore such pathways to understand how secondary traumatic experiences could affect the development of emotional exhaustion and psychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety and insomnia. Additionally, this study aims to reveal the role of various psychological characteristics as risk and protective factors for the development of psychiatry problems. This study also evaluated whether resilience could moderate the development of psychiatric problems from secondary traumatic experiences.

METHODS

Participants

The study population initially included 615 participants and finally enrolled 582 participants (157 men and 425 women) who completed questionnaires with a mean age of 35.00±8.03 years. The study population was enrolled from September 2015 to July 2017. This study included workers with secondary traumatic experience such as mental health worker, police officer, firefighter, paramedics, and nursing personnel working in a hospital’s inpatient and outpatient units who were willing to participate in this study. The population had been working at workplaces that includes 6 cities in South Korea. This study and all protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Soonchunhyang University Hospital (IRB number: 2015-05-013). It was performed in accordance with approved guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Psychological measures

To assess emotional exhaustion, the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) [7,23] was administered. The MBI is the gold standard for detecting burnout. Furthermore, it has been shown to have adequate performance with a stable factorial structure among nurses from different populations in varied contexts [24]. The MBI-GS, a 16-item questionnaire designed to assess the presence of burnout in healthcare providers, contains three subscales, each evaluating one of the underlying constructs of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement. Each subscale comprises several items. Each item is rated by the respondent on a 7-point Likert scale according to the frequency of occurrence (0=‘‘Never’’ to 6=‘‘Every day’’). The present study used emotional exhaustion, one subtype of MBI-GS, for the variable in the pathway model. There is a general consensus in the literature that emotional exhaustion is the central or core dimension of burnout [25,26].

To measure the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) scale were used [27,28]. To assess secondary traumatic stress, a secondary traumatic stress scale was administered. Secondary traumatic stress has been defined as “the natural, consequent behaviors and emotions resulting from knowledge about a traumatizing event experienced by a significant other.” [29] The scale consists of 17 items.

A 25-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale for measuring individual resilience in the face of stressful events was developed and evaluated. To assess individual stress, the 10-question Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was applied [30]. Quality of sleep was assessed with the Sleep Quality Scale [31]. This scale has 28 items and six factors [31].

Statistical analysis

To examine the moderating effect of resilience in the complex mediation model between the experience of secondary trauma and psychological symptoms, participants were divided into three groups: the low resilience group (n=197), which was the lower 33.3% of participants with resilience scores of 6 to 54, the middle resilience group (n=199), which was the middle 33.4% of participants with resilience score of 55 to 69, and the high resilience group (n=186) which was the higher 33.3% of participants with resilience score of 70 to 100.

Normality of variables by each group was tested before further analysis. Skewness over 2.0 and kurtosis over 7.0 were considered to reflect a moderately non-normal distribution [32]. Correlation analyses were performed to examine relationships between secondary traumatic stress and psychological characteristics. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

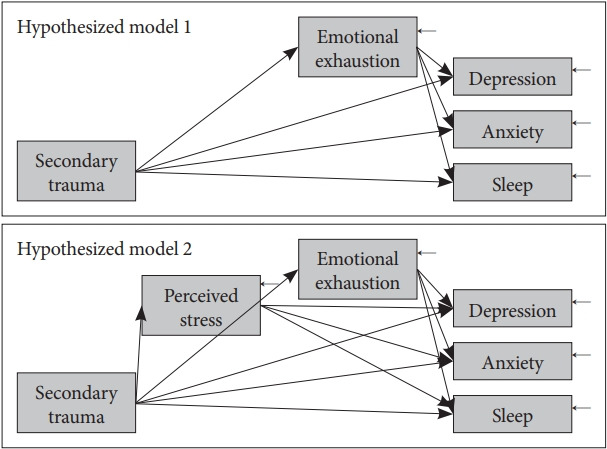

Based on correlation results, two models were hypothesized. One model is that secondary trauma can predict emotional exhaustion, which later predicts psychological symptoms. Another model is that secondary trauma can predict perceived stress, which then predicts emotional exhaustion and later predicts psychological symptoms.

Path analyses to determine a better-fit model were performed with the maximum likelihood estimator using AMOS 21.0. Chi-square test (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) indices were used to examine the goodness of fit of models. Cutoff points of indices were: CFI, NFI, TLI >0.90 and RMSEA <0.08 [33]. For model comparison, a comparison with the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) index was performed. The significance level was set at p<0.05 (two-tailed).

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses

A total of 582 healthcare providers completed the survey. They had a mean age (standard deviation) of 35.0 (8.0) years. Descriptive and psychological characteristics of healthcare providers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline demographic, and psychological characteristics in participants with low, middle, and high resilience

| Low resiliencea (N=197) | Middle resilienceb (N=199) | High resiliencec (N=186) | Total (N=582) | p | Post-hoc test using bonferroni | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean±SD or N (%) | ||||||

| Age (years) | 33.34±6.96 | 34.44±7.74 | 37.35±8.85 | 35.00±8.03 | <0.001 | a<c, b<c |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||||

| Male | 34 (17.3) | 50 (25.1) | 73 (39.2) | 157 (26.3) | ||

| Female | 163 (82.7) | 149 (74.9) | 113 (60.8) | 425 (71.1) | ||

| Education (years) | 15.43±1.29 | 15.61±1.36 | 15.49±1.72 | 15.51 (1.46) | 0.45 | |

| Marital status | 0.02 | |||||

| Single | 137 (69.5) | 120 (60.3) | 96 (51.6) | 353 (60.7) | ||

| Married | 55 (27.9) | 78 (39.2) | 86 (46.2) | 219 (37.6) | ||

| Other | 5 (2.6) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.2) | 10 (1.7) | ||

| Occupation status | 0.09 | |||||

| Manager level | 17 (8.6) | 26 (13.1) | 30 (16.1) | 73 (12.5) | ||

| Staff level | 180 (91.4) | 173 (86.9) | 156 (83.9) | 509 (87.5) | ||

| Resilience scale | 46.29±8.76 | 62.33±4.39 | 80.87±10.03 | 62.82±16.17 | <0.001 | a<b, a<c, b<c |

| Secondary traumatic stress scale | 43.65±12.33 | 35.83±11.04 | 29.49±12.05 | 36.45±13.13 | <0.001 | a>b, a>c, b>c |

| Perceived stress scale | 19.46±4.91 | 15.87±4.60 | 11.88±6.14 | 15.87±4.60 | <0.001 | a>b, a>c, b>c |

| Maslach burnout inventory | ||||||

| Emotional exhaustion | 25.73±6.00 | 22.53±6.02 | 18.18±7.86 | 22.22±7.32 | <0.001 | a>b, a>c, b>c |

| Depersonalization | 15.18±4.14 | 12.50±4.21 | 9.69±4.56 | 12.51±4.84 | <0.001 | a>b, a>c, b>c |

| Personal achievement | 25.63±4.60 | 28.84±4.48 | 33.39±5.02 | 29.21±5.66 | <0.001 | a<b, a<c, b<c |

| Depression scale | 8.92±6.08 | 5.87±4.70 | 4.25±4.90 | 6.38±5.60 | <0.001 | a>b, a>c, b>c |

| Anxiety scale | 5.44±4.65 | 2.96±2.95 | 2.17±3.08 | 3.55±3.90 | <0.001 | a>b, a>c |

| Sleep scale | 61.74±13.44 | 56.08±12.76 | 50.38±12.24 | 56.18±13.62 | <0.001 | a>b, a>c, b>c |

Correlation analyses among secondary traumatic stress, emotional exhaustion (subscale of MBI), and other psychological measures were executed by each group since all scores of each group were within the range of normal distribution. As shown in Table 2, all correlation coefficients were significant.

Table 2.

Correlations of psychological measures in participants with low, middle, and high resilience

| Measures | r |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Low resilience group (N=197) | ||||||

| 1. Secondary trauma | - | |||||

| 2. Perceived stress | 0.460*** | - | ||||

| 3. Emotional exhaustion | 0.406*** | 0.433*** | - | |||

| 4. Depression | 0.637*** | 0.590*** | 0.522*** | - | ||

| 5. Anxiety | 0.637*** | 0.585*** | 0.402*** | 0.826*** | - | |

| 6. Sleep | 0.588*** | 0.477*** | 0.508*** | 0.685*** | 0.68** | - |

| Middle resilience group (N=199) | ||||||

| 1. Secondary trauma | - | |||||

| 2. Perceived stress | 0.586*** | - | ||||

| 3. Emotional exhaustion | 0.435*** | 0.393*** | - | |||

| 4. Depression | 0.595*** | 0.539*** | 0.484*** | - | ||

| 5. Anxiety | 0.573*** | 0.554*** | 0.435*** | 0.729*** | - | |

| 6. Sleep | 0.519*** | 0.361*** | 0.427*** | 0.721*** | 0.452*** | - |

| High resilience group (N=186) | ||||||

| 1. Secondary trauma | - | |||||

| 2. Perceived stress | 0.708*** | - | ||||

| 3. Emotional exhaustion | 0.616*** | 0.614*** | - | |||

| 4. Depression | 0.724*** | 0.643*** | 0.670*** | - | ||

| 5. Anxiety | 0.715*** | 0.644*** | 0.618*** | 0.829*** | - | |

| 6. Sleep | 0.589*** | 0.435*** | 0.525*** | 0.682*** | 0.643*** | - |

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Two models were hypothesized for the path analysis after correlation analyses. The first model was composed of a path from secondary trauma score to emotional exhaustion and paths between emotional exhaustion and other psychological symptoms based on previous studies [4,9]. The second model was composed of an additional variable of perceived stress between secondary trauma and emotional exhaustion based on results of correlation analyses. These two hypothesized models are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Two hypothesized models for path analysis.

Path analyses

In order to reveal a better fitting model, the two hypothesized models were examined and compared with the AIC score of the pool of total participants. The AIC score of the first hypothesized model was 437.025 while that of the second hypothesized model was 173.278. The second hypothesized model fit the data better than the first model since its AIC was much lower than that of the first model. Thus, the second hypothesized model was accepted and analyzed by groups. Moreover, additional correlation paths among depression, anxiety, and sleep problems were included based on modification indices and earlier results of correlation analyses.

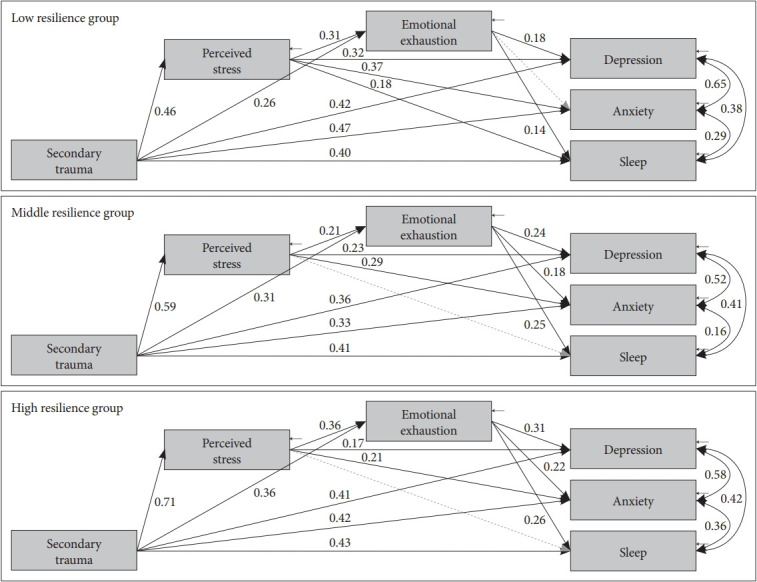

As shown in Table 3, results of path analyses of the three groups all showed great fit. Figure 2 presents the model with significant paths and standardized parameter estimates of each group. However, results were slightly different from the results depending on group. The score of secondary trauma experience significantly predicted perceived stress, emotional exhaustion, depression, anxiety, and sleep problems in all three groups.

Table 3.

Fitness indices of each model in participants with low, middle, and high resilience

| χ2 | df | p | CFI | NFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low resilience group | 1.422 | 1 | 0.233 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.990 | 0.046 |

| Middle resilience group | 0.229 | 1 | 0.632 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.022 | 0.000 |

| High resilience group | 0.547 | 1 | 0.460 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.009 | 0.000 |

CFI: comparative fit index, NFI: normed fit index, TLI: Tucker–Lewis index, RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation

Figure 2.

A comprehensive model from secondary traumatic experience to depression, anxiety, and sleep with mediators including perceived stress and emotional exhaustion in groups with low, middle, and high resilience.

In addition, the score of perceived stress significantly predicted emotional exhaustion, depression, anxiety, and sleep problems in all three groups. However, the path from emotional exhaustion to anxiety was only significant in the middle resilience group and the high resilience group (β=0.179, p=0.003; β=0.231, p<0.001, respectively), but not in the low resilience group (β=0.068, p=0.232). On the other hand, the direct path from the perceived stress score to sleep problems was only significant in the low resilience group (β=0.177, p=0.004), but not in the middle or the high resilience groups (β=0.035, p=0.632; β=-0.063, p=0.459, respectively).

Direct effects of perceived stress on depression and anxiety were the largest in the low resilience group (β=0.307, p<0.001; β=0.349, p<0.001, respectively), but the smallest in the high resilient group (β=0.148, p=0.030; β=0.194, p=0.006, respectively). However, direct effects of secondary trauma on perceived stress and emotional exhaustion were the largest in the high resilience group (β=0.708, p<0.001; β=0.365, p<0.001, respectively), but the smallest in the low resilient group (β=0.460, p<0.001; β=0.263, p<0.001, respectively). Table 4 shows regression weights, standard errors, and consistency ratios of the model of each group.

Table 4.

Regression weight, standard error, and consistency ratio of models

| Low resilience group |

Middle resilience group |

High resilience group |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized regression weights | SE | CR | Standardized regression weights | SE | CR | Standardized regression weights | SE | CR | |

| Secondary trauma → perceived stress | 0.460*** | 0.025 | 7.256 | 0.586*** | 0.024 | 10.188 | 0.708*** | 0.026 | 13.638 |

| Secondary trauma → emotional exhaustion | 0.263*** | 0.034 | 3.751 | 0.311*** | 0.042 | 4.005 | 0.365*** | 0.051 | 4.697 |

| Secondary trauma → depression | 0.405*** | 0.027 | 7.300 | 0.351*** | 0.029 | 5.202 | 0.423*** | 0.028 | 6.199 |

| Secondary trauma → anxiety | 0.448*** | 0.022 | 7.743 | 0.322*** | 0.018 | 4.665 | 0.436*** | 0.018 | 6.096 |

| Secondary trauma → sleep | 0.396*** | 0.067 | 6.439 | 0.393*** | 0.087 | 5.227 | 0.463*** | 0.087 | 5.384 |

| Perceived stress → emotional exhaustion | 0.312*** | 0.086 | 4.460 | 0.211** | 0.101 | 2.721 | 0.355*** | 0.099 | 4.569 |

| Perceived stress → depression | 0.307*** | 0.070 | 5.449 | 0.240*** | 0.067 | 3.628 | 0.148* | 0.054 | 2.167 |

| Perceived stress → anxiety | 0.349*** | 0.056 | 5.955 | 0.295*** | 0.043 | 4.357 | 0.194** | 0.036 | 2.724 |

| Perceived stress → sleep | 0.177** | 0.171 | 2.846 | 0.035 | 0.204 | 0.479 | -0.063 | 0.171 | -0.740 |

| Emotional exhaustion → depression | 0.224*** | 0.055 | 4.103 | 0.237*** | 0.046 | 3.992 | 0.319*** | 0.038 | 5.222 |

| Emotional exhaustion → anxiety | 0.068 | 0.044 | 1.195 | 0.179** | 0.030 | 2.933 | 0.231*** | 0.025 | 3.610 |

| Emotional exhaustion → sleep | 0.270*** | 0.136 | 4.464 | 0.242*** | 0.140 | 3.651 | 0.278*** | 0.120 | 3.620 |

| Depression error ↔ anxiety error | 0.646*** | 1.107 | 7.597 | 0.520*** | 0.619 | 6.49 | 0.582*** | 0.513 | 6.842 |

| Depression error ↔ sleep error | 0.381*** | 3.054 | 4.979 | 0.412*** | 2.796 | 5.364 | 0.415*** | 2.300 | 5.219 |

| Anxiety error ↔ sleep error | 0.289*** | 2.373 | 3.885 | 0.163* | 1.686 | 2.266 | 0.358*** | 1.481 | 4.582 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

SE: standard error, CR: consistency ratio

DISCUSSION

In the present study, several psychological factors were associated with secondary traumatic experiences among workers who had a job vulnerable to secondary traumatic experiences. Moreover, secondary traumatic experiences significantly affected perceived stress, emotional exhaustion, depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Further, a model was developed including paths from secondary traumatic experiences to psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia in workers both directly and indirectly through perceived stress and emotional exhaustion. More importantly, resilience moderated the path from perceived stress to emotional exhaustion and psychiatric problems.

In the present study, regardless of the degree of resilience, the model (path) showed that secondary traumatic experience could affect perceived stress, emotional exhaustion, and psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Thus, a model was developed including the paths from secondary traumatic experiences to psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia in workers both directly and indirectly through perceived stress and emotional exhaustion. This result is comparable to previous studies showing that secondary traumatic experiences could affect the development of depression in workers who help the population exposed to trauma [22,34,35]. Anxiety and insomnia in our study were also affected by secondary trauma. This is expected as they are often comorbid symptoms of depression [36].

Moreover, the pathway showed that emotional exhaustion, the core dimension of burnout [25,26], affected the development of depression and anxiety. Although various studies have reported the relation between depression and burnout [15,18], whether depression can be considered as a result of burnout or the opposite remains unclear [15]. Several studies have found that burnout is a different concept from depression [37,38] and that burnout can develop into depression [15,18,39]. However, other studies have revealed that burnout and depression are associated with each other bidirectionally and that they have similar and overlapping concept [17,40]. There is still confusion about the difference between burnout and depression [15] because depression and emotional exhaustion have common features such as mood states [15,41]. The present study contributes to prove the reasoning to distinguish depression from burnout. One study has shown that burnout can be used as a predictor of depressive symptoms in work life [15,41,42], especially work lives of healthcare providers who have a job that is vulnerable to secondary traumatic experiences.

Our study revealed that conditions such as depression and anxiety were related to greater emotional exhaustion. Similarly, emotional exhaustion was associated with greater health problems in the form of anxiety, depression, and insomnia [43]. A previous structural equation modeling study by Glass et al. [18] has concluded that a perceived lack of job control, in an expression similar to burnout, may indirectly drive depression. A literature review has noted that depression and burnout are distinct concepts. The causal relationship between them remains unclear [17]. Although the present study showed that burnout could serve as a predictor of depressive symptoms in work life [15,39], other studies have concluded that depressive symptoms may predict emotional exhaustion [16]. Further longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the causal relationship between depression and burnout.

This study disclosed the role of perceived stress as a mediator in the development of emotional exhaustion from secondary traumatic experiences. Regardless of the degree of resilience, the model (path) showed that perceived stress of individuals played a role in developing emotional exhaustion from secondary traumatic experience. According to conservation of resources theory, the general stress framework, the exposure to a broad range of stressors may deplete resources and lead to resource exhaustion [44]. Stresses to work-related indirect exposure to traumatic events are examples of such broad range of stressors. This broad range of stressors may consequently lead to exhaustion of a broad range of resources [35]. Emotional exhaustion may represent one of the facets of loss/exhaustion of resources [35].

Moreover, our results showed that secondary traumatic experiences could affect the development of emotional exhaustion. Cieslak et al. [45] have indicated that there are strong associations between burnout and secondary traumatic stresses among human services professionals. Although there is no evidence clarifying whether secondary traumatic stresses can lead to burnout or burnout leads to secondary traumatic stresses [35], results of the present study were in line with our previous study on nursing personnel which showed that secondary traumatic experiences could predict emotional exhaustion in a regression analysis [16].

Results of this study showed that resilience was negatively associated with various psychopathology such as depression, anxiety, burnout, and secondary traumatic stresses among workers who had a job vulnerable to secondary traumatic experiences. Additionally, the higher the resilience, the lower the direct effect from perceived stress to depression and anxiety in the population. The current findings add to a growing body of evidence on the healthy effect of resilience [46,47]. Previous studies have suggested one potential explanation for the role of resilience is that it can affect the capacity of coping successfully with adversity [48]. Higher resilience is usually associated with more positive emotion and increased emotional flexibility, which may reduce the likelihood of depression and post-traumatic reactions [22,49-51]. Ying et al. [22] have suggested that individual difference in resilience appears to be useful to understand the effective adaptation to extreme adversity. Additionally, the finding of this study is consistent with previous studies showing that dispositional resilience plays an important role in buffering the effect of the frequency of daily hassles on concurrent levels of symptoms distress [22,52]. Findings of the current study suggest that resilience can serve as a ‘‘buffer’’ against perceptions of stress and psychopathology related to secondary traumatic experiences.

However, the higher the resilience, the lower the direct effect from secondary traumatic experiences to perceived stress and emotional exhaustion in the population. This suggests that individuals with higher resilience might be less influenced by secondary traumatic events. However, the impact of secondary trauma might be higher than that in those with lower trait resilience. While those individuals with higher levels of resilience did show a less significant increase in secondary traumatic stresses in the workplace, resilience might have a considerable impact on the development of burnouts and psychiatric problems. That is, individuals with higher resilience might have higher predictive powers of secondary traumatic experiences than those with lower levels of resilience. Therefore, not only understanding how one can develop and enhance resilience, but also coping and managing perceived stress response are of great importance to prevent the development of psychiatric illnesses such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder.

This study has some limitations. First, there was a lack of information on several occupational covariates that might be associated with secondary traumatic experiences and burnout, such as types of secondary trauma or additional work performed or workload. Therefore, we could not include them in the analysis. Because the present study included various workers such as police officers, firefighters, social workers, and nurses to show various work conditions known to influence secondary traumatic experiences, this study could not apply one criterion on occupational status. Further studies that include additional explanatory variables related to secondary trauma and burnout with larger sample sizes are needed. Second, scales used in this study were self-report measures. However, these are reliable and validated instruments that have been widely used in other studies. Additionally, although we used path analysis to test predictive value, the present study was a cross-sectional study. Further longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the causal relationship between secondary traumatic stress and psychopathologies. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to populations of other ethnicities.

Despite the above limitations, the present study also has some strengths. This is the first study to make and verify the possible candidate pathway from secondary traumatic stress to the development of emotional exhaustion and psychiatric problems in those with high-risk profession. Second, identification of protective and risk factors associated with psychiatric problems related to secondary traumatic stresses may help us identify groups at high risk of exhaustion and potentially modifiable risk factors that contribute to emotional exhaustion, a critical step for developing effective preventative strategies for this vulnerable population. For example, professions with less resilience and higher perceived stress could be supported by additional assistants or might receive stress management training to prevent burnout and depression. Third, this study used a relatively large sample size to achieve the study aims. Finally, the present study can help us determine whether interventions might be effective in preventing psychiatric problems in high-risk professions. Identifying the target of interventions could help professions who are at risk of exhaustion to choose proper psychological interventions.

In conclusion, our data showed that secondary traumatic experiences significantly affected perceived stress, emotional exhaustion, depression, anxiety, and insomnia. A model was developed including paths from secondary traumatic experiences to psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia in workers both directly and indirectly through perceived stress and emotional exhaustion. Moreover, the path revealed that resilience could moderate the path from perceived stress to emotional exhaustion and psychiatric problems. Our results might offer insight into the necessities of beforehand interventions to prevent burnout and depression in high risk professions that are vulnerable to secondary traumatic experiences.

Acknowledgments

Our study was supported by the grants from the National Center for Mental Health Research & Education, the Seoul National Hospital, Republic of Korea (HM15C1113) and Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: Ji Sun Kim. Data curation: Min Jin Jin. Formal analysis: Min Jin Jin. Funding acquisition: Hwa-Young Lee. Investigation: Ho-Sung Lee, Young Joon Kwon, Se Hoon Shim, Bum-Sung Choi, Dong-Woo Lee, Jong-Woo Paik, Boung Chul Lee, Sung-Won Jung. Methodology: Min Jin Jin. Project administaration: Ho-Sung Lee, Young Joon Kwon, Se Hoon Shim, Bum-Sung Choi, Dong-Woo Lee, Jong-Woo Paik, Boung Chul Lee, Sung-Won Jung. Resources: Hwa-Young Lee. Software: Ji Sun Kim. Supervision: Ho-Sung Lee, Young Joon Kwon, Se Hoon Shim, Bum-Sung Choi, Dong-Woo Lee, Jong-Woo Paik, Boung Chul Lee, Sung-Won Jung, Hwa-Young Lee. Validation: Hwa-Young Lee. Visualization: Min Jin Jin. Writing —original draft: Min Jin Jin and Ji Sun Kim. Writing—review & editing: Hwa-Young Lee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Figley CR. Compassion Fatigue as Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder: An Overview. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newell JM, MacNeil GA. Professional burnout, vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue: A review of theoretical terms, risk factors, and preventive methods for clinicians and researchers. Best Pract Ment Health Int J. 2010;6:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palm KM, Polusny MA, Follette VM. Vicarious traumatization: potential hazards and interventions for disaster and trauma workers. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;19:73–78. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salston M, Figley CR. Secondary traumatic stress effects of working with survivors of criminal victimization. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16:167–174. doi: 10.1023/A:1022899207206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams RE, Boscarino JA, Figley CR. Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: a validation study. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:103–108. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bride BE, Radney M, Figley CR. Measuring compassion fatigue. Clin Soc Work J. 2007;35:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright TA, Cropanzano R. Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. J Appl Psychol. 1998;83:486–493. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sodeke-Gregson EA, Holttum S, Billings J. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in UK therapists who work with adult trauma clients. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013:4. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.21869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prosser D, Johnson S, Kuipers E, Szmukler G, Bebbington P, Thornicroft G. Mental health, “burnout’ and job satisfaction among hospital and community-based mental health staff. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:334–337. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant HB, Lavery CF, Decarlo J. An exploratory study of police officers: low compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2793. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greinacher A, Derezza-Greeven C, Herzog W, Nikendei C. Secondary traumatization in first responders: a systematic review. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10:1562840. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1562840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare staff well-being, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, White DA, Adams EL, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papathanasiou IV. Work-related mental consequences: mplications of burnout on mental health status among health care roviders. Acta Inform Med. 2015;23:22–28. doi: 10.5455/aim.2015.23.22-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi BS, Kim JS, Lee DW, Paik JW, Lee BC, Lee JW, et al. Factors associated with emotional exhaustion in South Korean nurses: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Investig. 2018;15:670–676. doi: 10.30773/pi.2017.12.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass D, McKnight J. Perceived control, depressive symptomatology, and professional burnout: A review of the evidence. Psychol Health. 1996;11:23–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glass DC, McKnight JD, Valdimarsdottir H. Depression, burnout, and perceptions of control in hospital nurses. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:147–155. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edward KL. The phenomenon of resilience in crisis care mental health clinicians. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2005;14:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard S, Johnson B. Resilient teachers: resisting stress and burnout. Soc Psychol Educ. 2004;7:399–420. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manzano G, Ayala-Calvo JC. Emotional exhaustion of nursing staff: influence of emotional annoyance and resilience. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying L, Wu X, Lin C, Jiang L. Traumatic severity and trait resilience as predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depressive symptoms among adolescent survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin KH. The Maslach Bunout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS): an application in South Korea. Korean J Indust Organ Psychol. 2003;16:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poghosyan L, Aiken LH, Sloane DM. Factor structure of the Maslach burnout inventory: an analysis of data from large scale cross-sectional surveys of nurses from eight countries. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:894–902. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaines J, Jermier J. Emotional exhaustion in a high stress organization. Acad Manag J. 1983;26:567–586. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonnentag S, Kuttler I, Fritz C. On stressors, emotional exhaustion, and need for recovery: a multi-source study on the benefits of psychological detachment. J Vocation Behav. 2010;76:355–365. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yegidis B, Figley CR. Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale. Res Soc Work Pract. 2004;14:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi H, Shin K, Shin C. Development of the sleep quality scale. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 3rd Edition. New York: The Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilroy PJ, Carroll L, Murra J. A preliminary survey of counseling psychologists’ personal experiences with depression and treatment. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2002;33:402–407. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoji K, Lesnierowska M, Smoktunowicz E, Bock J, Luszczynska A, Benight CC, et al. What comes first, job burnout or secondary traumatic stress? Findings from two longitudinal studies from the U.S. and Poland. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D Rossler W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep. 2008;31:473–480. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:499–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iacovides A, Fountoulakis KN, Moysidou C, Ierodiakonou C. Burnout in nursing staff: is there a relationship between depression and burnout? Int J Psychiatry Med. 1999;29:421–433. doi: 10.2190/5YHH-4CVF-99M4-MJ28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duquette A, Kerouac S, Sandhu BK, Beaudet L. Factors related to nursing burnout: a review of empirical knowledge. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1994;15:337–358. doi: 10.3109/01612849409006913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iacovides A, Fountoulakis KN, Kaprinis S, Kaprinis G. The relationship between job stress, burnout and clinical depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;75:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka JS, Huba GJ. Confirmatory hierarchical factor analysis of psychological distress measures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;46:621–635. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Firth H, McKeown P, McIntee J, Britton P. Professional depression, ‘burnout’ and personality in longstay nursing. Int J Nurs Stud. 1987;24:227–237. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(87)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Servellen G, Topf M, Leake B. Personality hardiness, work-related stress, and health in hospital nurses. Hosp Top. 1994;72:34–39. doi: 10.1080/00185868.1994.9948484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cieslak R, Shoji K, Douglas A, Melville E, Luszczynska A, Benight CC. A meta-analysis of the relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychol Serv. 2014;11:75–86. doi: 10.1037/a0033798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonanno GA. Clarifying and extending the construct of adult resilience. Am Psychol. 2005;60:265–267. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ong AD, Zautra AJ, Reid MC. Psychological resilience predicts decreases in pain catastrophizing through positive emotions. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:516–523. doi: 10.1037/a0019384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Block J, Kremen AM. IQ and ego-resiliency: conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:349–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, Wallace KA. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91:730–749. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86:320–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waugh CE, Thompson RJ, Gotlib IH. Flexible emotional responsiveness in trait resilience. Emotion. 2011;11:1059–1067. doi: 10.1037/a0021786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pinquart M. Moderating effects of dispositional resilience on associations between hassles and psychological distress. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2009;30:53–60. [Google Scholar]