Highlights

-

•

Combined femoral arterial and nerve injury is rare in proximal femur fracture cases.

-

•

As far as for our knowledge it is the first to be reported.

-

•

We report a 42-year-old diagnosed with a left subtrochanteric femur fracture.

-

•

Although promptly taken to surgery, leg amputation was necessary a week later.

-

•

Blunt femoral injuries are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates.

Keywords: Amputation, Proximal femur, Femoral artery, Femoral nerve, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Combined femoral arterial and nerve injury does not often occur in cases of proximal femur fracture (hip fracture) and is often overlooked in the emergency medical setting. Physicians should be aware of this rare but possible combination of injuries, which can lead to devastating and disabling patient outcomes.

Presentation of case

A 42-year-old Ethiopian male was struck by a steel pipe, rushed to the emergency room, and diagnosed with a left subtrochanteric fracture of the femur. Although promptly taken to surgery for fixation and exploration of the femoral artery, it became necessary to amputate his leg 1 week later.

Discussion

Blunt injuries to the femoral nerve and femoral arterial tree are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. These injuries should not be overlooked when diagnosing patients with blunt trauma to the femur.

Conclusion

When treating patients presenting with blunt trauma to the femur, several factors may obfuscate the clinician’s need to perform a thorough examination of the femoral artery and femoral nerves. Among other things, the patient may not immediately present with signs of hemodynamic instability, similar to our reported case. The clinician may also be invested in treating the patient according to the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol. When treating blunt hip trauma patients, clinicians should recognize that even blunt trauma to the femur may critically damage the femoral artery and nerve.

1. Introduction

Femoral neurovascular bundle transection is a devastating injury not commonly associated with blunt trauma to the proximal femur: it is more commonly associated with penetrating injuries to the femur such as gunshot wounds [1]. However, even blunt trauma around the hip may cause femoral artery transection, which may in turn result in morbidity, death, hemodynamic instability, limb loss, and permanent physical disability [1]. Blunt trauma to the femur may also damage the femoral nerve, thereby impairing knee extension and other basic motor functions [2]. Cases of combined femoral artery transection and femoral nerve injuries caused by blunt trauma to the proximal femur have rarely been reported in the literature. Here, we present such a case, treated with a contralateral saphenous vein graft in the emergency department of a public hospital, with a devastating outcome. We encourage clinicians to recognize and take steps to rule out femoral artery involvement when managing trauma to the proximal femur. Our reporting of this case followed the Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Checklist and the guidelines of the paper: Agha RA, Borrelli MR, Farwana R, Koshy K, Fowler A, Orgill DP. The SCARE 2018 Statement: Updating Consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guidelines, International Journal of Surgery 2018; 60: 132–136 [3]. The patient gave informed consent for this case report to be published. Patient privacy and confidentiality was assured, no patient identifiers are presented, and all data are secured within the hospital records department (Fig. 1).

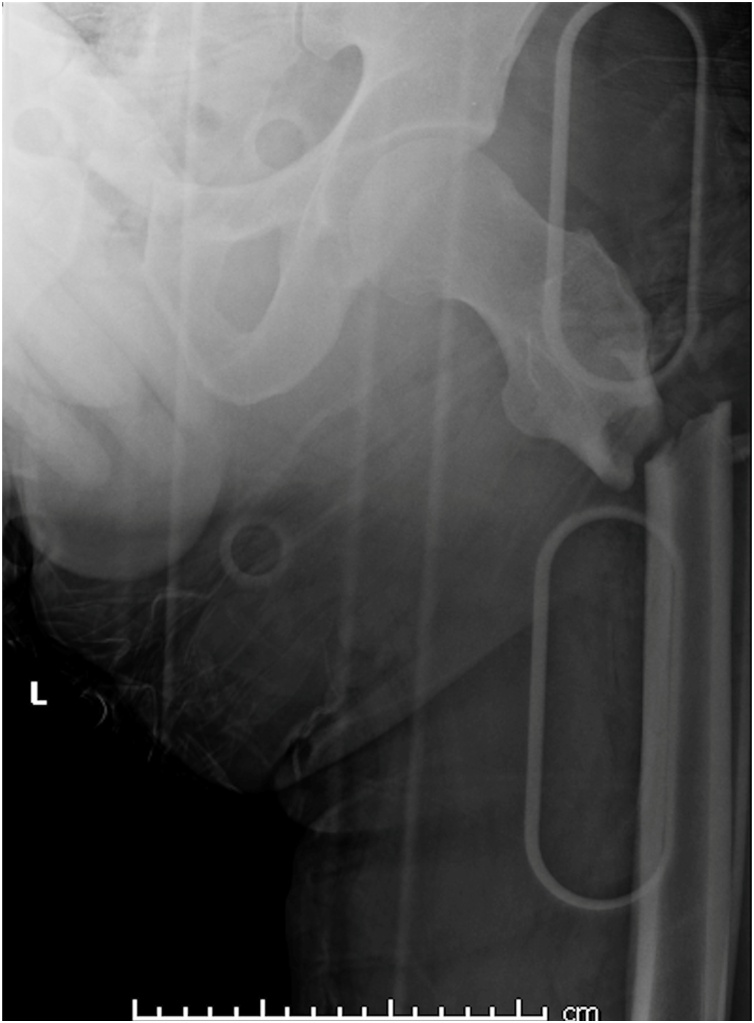

Fig. 1.

X-rays showing left subtrochanteric femoral fracture.

2. Presentation of case

A 42-year-old Ethiopian male labor from an underprivileged socioeconomic and educational background. The patient is medically free with unremarkable drug and family history. He was taken by ambulance from his workplace to the emergency department of our hospital two hours after being hit by a steel pipe on the anterior proximal thigh. Patient was complaining of sever pain following the incident. Upon arrival, he was conscious, alert, and oriented. He complained mostly of left hip pain. In the Emergency Department, his vital signs (including blood pressure and heart rate) were within normal range, and no clear deformity was noted. There was a small wound, about 3 cm around, with mild blood oozing, on the left anterior proximal thigh. There were bruise lines, apparently from the impact of the steel pipe, transversely along the anterior proximal thigh. There were similar bruise lines on the lower abdomen and lower thigh. His limbs pulses were impalpable. During the primary survey, his vitals started to rapidly deteriorate; his blood pressure dropped 90/50 mmHg and his pulse rate increased to 115 beat per minute. X-rays showed left subtrochanteric femoral fracture. After resuscitation the patient’s left lower limb was still not audible on Doppler sonography. Arterial injury was highly suspected. Computed tomography angiography showed contrast at the left external iliac artery, contrast at the bifurcation of the common femoral artery at the fracture site, and a total loss of contrast opacification in the rest of the femoral arterial tree. The patient was immediately rushed to the operating room for exploration within two hours from presentation and surgery duration was about 3 h. An external fixator was applied to the pelvis and to the proximal and distal fragments by the orthopedic surgeon on duty. Using an anterior approach, the vascular surgeon observed that the superficial and deep femoral arteries had been transected, as had the femoral vein and nerve. The vascular surgeon used a contralateral saphenous vein graft to bypass and repair. The surgery was uneventful and the patient was started on anticoagulant protocol to prevent vascular graft thrombosis. Postoperatively, the patient’s pulse was audible by Doppler ultrasound. However, the patient had a diminished patellar reflex and could not extend his knee. For 1 week thereafter, the patient’s leg was becoming cool and pale, with fading pulses. The vascular surgeon ultimately assessed the leg as nonviable and preformed above knee amputation.

Special attention payed to wound healing and avoiding infection and wound dehiscence, hence, patient was covered with antibiotics for 2 weeks until clips where removed.

Post amputation protocol included analgesia, anticoagulants, dressing change by the team and mobilization using crutches. Patient was kept in the hospital during this period.

3. Discussion

The quadriceps, pectineus, and sartorius muscles receive motor innervation from the femoral nerve [4]. The femoral nerve also innervates the anteromedial thigh and medial leg. Therefore, femoral nerve injury will cause sensorimotor sequelae in the patient, including weak knee extensors, absent patellar reflex, and sensory loss in the medial leg or anterior thigh [2]. Femoral nerve injury is more frequently caused by surgical complications than by external trauma to the femur [2]. It may also be caused by penetrating trauma, hemorrhage, stretching of the nerve during excessive hip extension, and medical catheterization [5]. Patients with femoral nerve injury may undergo physiotherapy to reduce muscle atrophy, and the risk of deep vein thrombosis. If the patient has motor function, orthosis may be used to stabilize the knee [6].

The femoral artery lies anterior to the femoral head. Its anatomy is variable and depends on many factors [7]. The common femoral artery often occupies a fixed position, making it vulnerable to injuries that befall the groin [8]. Clinical signs of femoral artery injury are diminished pulse, limb ischemia, enlarging hematoma, and bleeding from the artery. Where these “hard” signs are present, clinical management includes an angiogram and surgical intervention [1]. Soft signs of femoral artery injury include nonexpanding hematoma, major wounds, and uncontrolled hypotension. In these cases, femoral artery injury is more difficult to recognize, and additional diagnostic tools may be needed, including ankle-brachial index testing, computed tomography angiography, or conventional angiography [1].

Surgically, proximal dissection must be extended as needed to expose more of the vessel to acutely restore blood flow [9]. Intraoperatively, if revascularization must be delayed (as when dealing with fracture fixation, soft tissue injury, or vein harvesting), temporary intravascular shunting may be utilized [9]. Lower extremity trauma with concomitant orthopedic and vascular injury is associated with a high degree of limb loss. Despite arterial repair, many patients will require amputation [10].

In 2001, Suliman et al. described a combined femoral artery and femoral vein injury caused by a blow to the femur which produced extreme hyperextension and abduction forces in the body. Their review of the literature included 20 cases involving blows to a lower limb, with two resulting in complete transection of the superficial femoral artery and superficial femoral vein. One case involved a pedestrian. Another case involved a heavy object that fell on the patient’s groin [9]. In four cases, the common femoral artery was completely transected [9]. The most common injury (occurring in 11 cases) was femoral artery intimal injury. One case involved a delayed diagnosis of common femoral artery [9]. According to Suliman et al., motor scooter handlebar syndrome was frequently associated with femoral artery injury [9].

In our case, the patient’s subtrochanteric fracture caused anterolateral displacement of the distal femur fragment that may resulted in the combined injury. The direction of displacement was atypical. Usually, the proximal fragment abducts, externally rotates, and goes into flexion due to the pulling forces of the surrounding muscles (including the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, short external rotators, and iliopsoas) [11]. Normally, the distal fragment also adducts due to the pulling forces of the gracilis and adductor muscles [11]. In our case, the atypical direction of displacement could be the cause of external iliac artery injury (along with the femoral artery and nerve). To our knowledge, cases of this type have not been earlier reported especially with proximal femur fracture.

Unfortunately, the patient ended up with amputation, although patient was managed by saphenous vein graft to restore his limb perfusion. This might highlight the need for an increased suspicion of a combined femoral nerve and artery injury following an atypical proximal femur fracture direction. A computed telegram angiography post op might’ve been helpful to pick any post-op hematoma affecting the graft patency despite the audible triphasic doppler signal.

4. Conclusion

When assessing any fracture of the proximal femur, the importance of a through distal pulse and nerve examination cannot be overstated. Clinicians often overlook femoral artery and nerve injury when concentrating on other legitimate concerns, including the patient’s pain and the need to adhere to the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol. Plainly, any delay may lead to devastating outcomes for the patient, as in our case. To avoid missing a vascular injury, we encourage two things: augmenting the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol to include examination of the pulses by palpation or Doppler ultrasound.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical approval

Ministry of Heath Saudi Arabia.

IRB No. 20-124E.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

First author Abdulaziz AlKheraiji: Major writing role; also obtained approval of the Ministry of Health.

Co author Abdulaziz AlHakbani: Data collection and editing.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Abdulaziz AlKheraiji.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally pee reviewed.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Naif Alamir for facilitating and offering access to patient and data base.

Contributor Information

Abdulaziz AlKheraiji, Email: a.alkheraiji@mu.edu.sa.

Abdulaziz AlHakbani, Email: amhakbani@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Dharia R., Perinjelil V., Nallani R., Al Daoud F., Sachwani-Daswani G., Mercer L. Superficial femoral artery transection following penetrating trauma. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018;2018(6):rjy137. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjy137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Amelio L.F., Musser D.J., Rhodes M. Bilateral femoral nerve neuropathy following blunt trauma. Case report. J. Neurosurg. 1990;73:630–632. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.4.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P. The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gocmen-Mas N., Aksu F., Edizer M., Magden O., Tayfur V., Seyhan T. The arterial anatomy of the saphenous flap: a cadaveric study. Folia Morphol. 2012;71(1):10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Ghanem M., Malik A.A., Azzam A., Yacoub H.A., Qureshi A.I., Souayah N. Occurrence of femoral nerve injury among patients undergoing transfemoral percutaneous catheterization procedures in the United States. J. Vasc. Interv. Neurol. 2017;9(4):54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore A., Stringer M.D. Iatrogenic femoral nerve injury: a systematic review. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2011;33:649–658. doi: 10.1007/s00276-011-0791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn H.Y., Lee H.J., Yang J.H., Yi J.S., Lee I.W. Assessment of the optimal site of femoral artery puncture and angiographic anatomical study of the common femoral artery. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2014;56(2):91–97. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2014.56.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadeed J.G., Gregory K., Albaugh D.O., Alexander J.B., Ross S.E., Ierardi R.P. Blunt handlebar injury of the common femoral artery: a case report. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2005;19(3):414–417. doi: 10.1007/s10016-005-0017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suliman A., Wasif Ali M., Kansal N., Tian Y., Angle N., Coimbra R. Complete femoral artery and vein avulsion from a hyperextension injury: a case report and literature review. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2009;23(3) doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.05.005. 411.e9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moniz M.P., Ombrellaro M.P., Stevens S.L., Freeman M.B., Diamond D.L., Goldman M.H. Concomitant orthopedic and vascular injuries as predictors for limb loss in blunt lower extremity trauma. Am. Surg. 1997;63(1):24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson C., Tanios M., Ebraheim N. Management of subtrochanteric proximal femur fractures: a review of recent literature. Adv. Orthop. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/1326701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]