Abstract

Azole-resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus is a worldwide medical concern complicating the management of aspergillosis (IA). Herein, we report the clonal spread of environmental triazole resistant A. fumigatus isolates in Iran. In this study, 63 A. fumigatus isolates were collected from 300 compost samples plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar supplemented with itraconazole (ITR) and voriconazole (VOR). Forty-four isolates had the TR34/L98H mutation and three isolates a TR46/Y121F/T289A resistance mechanism, while two isolates harbored a M172V substitution in cyp51A. Fourteen azole resistant isolates had no mutations in cyp51A. We found that 41 out of 44 A. fumigatus strains with the TR34/L98H mutation, isolated from compost in 13 different Iranian cities, shared the same allele across all nine examined microsatellite loci. Clonal expansion of triazole resistant A. fumigatus in this study emphasizes the importance of establishing antifungal resistance surveillance studies to monitor clinical Aspergillus isolates in Iran, as well as screening for azole resistance in environmental A. fumigatus isolates.

Keywords: Aspergillus fumigatus, azole resistance, compost, TR34/L98H, TR46/Y121F/T289A

1. Introduction

Aspergillus fumigatus is the most common agent of various forms of aspergillosis, including allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA), aspergilloma, and invasive aspergillosis (IA) [1]. Voriconazole (VOR) is the recommended primary and most effective therapy in the management of aspergillosis [2]. However, azole resistant A. fumigatus isolates are increasingly found worldwide with major epidemiological and clinical implications [3,4]. Therapeutic failure caused by azole-resistant A. fumigatus is becoming a significant concern to clinicians who are caring for patients at high risk for IA [1,4,5,6,7,8]. Azole resistance in A. fumigatus is mainly linked to cyp51A-mediated resistance mechanism, such as a 34-basepair (bp) sequence tandem repeat (TR34) in the promoter region of the cyp51A gene, in combination with a L98H substitution and a 46 bp tandem repeat (TR46) in the cyp51A promoter in combination with two amino acid changes (Y121F and T289A) in the CYP51A protein (TR46/Y121F/T289A) [9]. Isolates carrying these mutations exhibit a pan-azole resistant phenotype that can develop through long-term treatment with azole antifungals in the clinical setting or extensive exposure of the fungus to azole compounds in the environment [10,11]. Azole-resistant A. fumigatus with the TR34/L98H mutation isolated from environmental and clinical samples have been reported earlier in Iran, and we recently reported the occurrence of TR46/Y121F/T289A mutations in the cyp51A gene in A. fumigatus isolates from compost [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. High concentrations of azole-resistant A. fumigatus spores are released during incomplete composting processes, especially when azole residues from agricultural waste are present [19]. Agricultural use of fungicides has driven the emergence and spread of azole-resistant A. fumigatus. The existence of an environmental route of azole resistance development involves serious risks for patients, as well, as they can become infected with azole resistant A. fumigatus strains before starting their treatment [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Notably, genetic exploration of azole resistant A. fumigatus strains indicates that isolates with the TR34/L98H allele are less genetically variable than susceptible isolates [12,23]. For instance, analysis of azole resistant A. fumigatus isolates in the Netherlands showed five distinct genotype groups in this country, while all the azole resistant isolates with the TR34/L98H mutation belonged to one group [5]. On the other hand, all clinical and environmental azole resistant A. fumigatus strains carrying TR34/L98H obtained from India were genetically identical [14]. These studies illustrate that A. fumigatus carrying this azole resistance mutation may preferentially spread clonal within a population. Major data gaps remain regarding the genotype distribution of azole resistance A. fumigatus in Iran. As ongoing reports indicate an expansion in the frequency of azole resistant A. fumigatus isolates worldwide, understanding the genetic structure of this potentially lethal fungus is critical. In this study, the genetic characterization of azole resistant A. fumigatus isolated from compost samples in Iran was explored.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolate Collection

According to a previously described protocol, commercial and home-made compost samples from different region of Iran (located about 300 km apart) were collected. To recover A. fumigatus strains, 1 cm2 of compost was dissolved in 5 mL sterile saline solution containing Tween 40 (0.05%), vortexed, and allowed to settle. For primary screening of azole-resistant A. fumigatus strains, 100 μL supernatant was plated on a Sabouraud dextrose agar plate (SDA; Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), supplemented with 4 and 1 mg/L itraconazole and voriconazole, respectively, and incubated at 45 °C for 72 h in the dark [17]. Molecular identification of all A. fumigatus isolates that grew on the supplemented plate was performed with sequencing of the partial beta-tubulin gene as previously described [16].

2.2. In Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by broth microdilution susceptibility testing according to the methods in the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) reference standard (M38) [25]. For the preparation of the microdilution trays, itraconazole (Janssen, Beerse, Belgium) and voriconazole (Pfizer, Sandwich, UK) were obtained from the respective manufacturers as reagent-grade powders. All drugs were dissolved in 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma, Zwijndrecht, the Netherlands) and were prepared at a final concentration of 0.031–16 mg/L. Paecilomyces variotii (ATCC 22319) and Candida parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) were used as quality controls [25].

2.3. Detection of Cyp51a Gene Mutations

All A. fumigatus isolates were subjected to a mixed-format real-time PCR assay specific for TR34/L98H and TR46/Y121F/T289A mutations of cyp51A gene leading to triazole resistance in A. fumigatus as described previously [26]. Those isolates with negative or inconclusive results in the real-time PCR assay, were further evaluated by sequencing the cyp51A gene as described previously [27].

2.4. Microsatellite Genotyping

Genotyping of all A. fumigatus isolates was performed with a panel of nine short tandem repeats (STRs) loci (namely short tandem repeats Aspergillus fumigatus (STRAf) 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, 4A, 4B, and 4C), as previously described [28]. Genotypes were considered identical when they showed the same alleles for all nine loci [29,30]. Finally, the genetic relatedness between Iranian isolates from compost and 633 resistant A. fumigatus strains with clinical or environmental sources collected during 2001–2019 from different countries (The Netherlands, India, United Kingdom, Tanzania, France, Colombia, Romania, Ireland, China, Kuwait, Germany, and Japan) and previous Iranian isolates in the database at the Center of Expertise in Mycology, Radboudumc/Canisius-Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis (CWZ), in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, already barcoded using a panel of nine short tandem repeat loci, were analysed using BioNumerics software v7.6.1 (Applied Maths, Saint-Martens-Latem, Belgium).

3. Results

3.1. Triazole Resistant A. fumigatus with Mutation in cyp51A Gene

A total of 63 A. fumigatus colonies from 300 compost samples were obtained from SDA supplemented with itraconazole and voriconazole. Of these, 55 A. fumigatus isolates had high MICs of itraconazole (≥8 mg/L) and voriconazole (≥2 mg/L) by in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing. Exploring the mechanisms of resistance in these isolates by sequencing cyp51A and its promoter region showed that 44 isolates harbored the TR34/L98H mutation, three isolates the TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation and two isolates a M172V mutation. No mutations were found in 14 resistant isolates. Data of resistant isolates are summarized in Table 1. Details of isolates with the TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation have been previously described [17].

Table 1.

Description of all A. fumigatus isolates from compost.

| Strain | Longitude and Latitude of Sampling | MIC (mg/L) | 3 STRAf | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ITR | 2 VOR | Mutation in cyp51A | 2A | 2B | 2C | 3A | 3B | 3C | 4A | 4B | 4C | ||

| mn224 | 35.9548° N, 52.1100° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn225 | 36.6717° N, 52.4439° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn226 | 36.6717° N, 52.4439° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn229 | 36.6717° N, 52.4439° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn227 | 36.7049° N, 52.6547° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn228 | 36.6329° N, 52.2667° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn231 | 36.4684° N, 52.8634° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn235 | 36.4684° N, 52.8634° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn232 | 36.4684° N, 52.8634° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn241 | 36.4684° N, 52.8634° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn233 | 36.6858° N, 52.5265° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn234 | 36.6858° N, 52.5265° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn236 | 36.4676° N, 52.3507° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn246 | 36.4676° N, 52.3507° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn247 | 36.5971° N, 52.6654° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn250 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn251 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn252 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn253 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn254 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn255 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn256 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn257 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn258 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn260 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn261 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn263 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn265 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn266 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn267 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn268 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn269 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn270 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn271 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn272 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn273 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn274 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn277 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn279 | 36.9268° N, 50.6431° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn280 | 36.7284° N, 53.8102° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| mn281 | 36.7284° N, 53.8102° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 22 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| IFRC: 1854 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 2 | TR34/L98H | 14 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 27 |

| IFRC: 1858 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 8 | 1 | TR34/L98H | 13 | 21 | 8 | 32 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| IFRC: 1866 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 8 | TR34/L98H | 14 | 24 | 14 | 31 | 9 | 31 | 10 | 9 | 5 |

| mn248 | 36.6329° N, 52.2667° E | 16 | 16 | M172V | 11 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 29 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 8 |

| IFRC: 1867 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 16 | M172V | 11 | 16 | 9 | 19 | 20 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| IFRC: 1860 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 0.125 | Wild type | 27 | 18 | 16 | 7 | 12 | 28 | 27 | 5 | 8 |

| IFRC: 1868 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 16 | Wild type | 27 | 18 | 16 | 7 | 12 | 28 | 27 | 5 | 8 |

| IFRC: 1862 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 0.5 | Wild type | 27 | 20 | 13 | 8 | 14 | 35 | 10 | 11 | 10 |

| IFRC: 1864 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 0.25 | Wild type | 20 | 10 | 8 | 37 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 15 |

| IFRC: 1859 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 16 | 0.25 | Wild type | 21 | 20 | 14 | 30 | 21 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 5 |

| mn245 | 36.7049° N, 52.6547° E | 16 | 1 | Wild type | 13 | 19 | 8 | 34 | 29 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| mn276 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | Wild type | 18 | 22 | 15 | 43 | 13 | 27 | 13 | 8 | 10 |

| mn278 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 16 | 2 | Wild type | 24 | 10 | 10 | 28 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 15 |

| mn249 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 0.125 | 0.5 | Wild type | 23 | 22 | 14 | 44 | 12 | 27 | 13 | 8 | 7 |

| mn223 | 36.5659° N, 53.0586° E | 0.125 | 0.5 | Wild type | 22 | 23 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 6 |

| mn240 | 36.6329° N, 52.2667° E | 0.5 | 1 | Wild type | 11 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 29 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| mn242 | 36.6329° N, 52.2667° E | 0.125 | 0.5 | Wild type | 24 | 22 | 18 | 24 | 13 | 17 | 9 | 8 | 10 |

| mn230 | 36.6717° N, 52.4439° E | 0.5 | 0.5 | Wild type | 24 | 20 | 18 | 22 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 9 |

| IFRC: 1863 | 35.6892° N, 51.3890° E | 4 | 0.125 | Wild type | 24 | 18 | 15 | 94 | 10 | 6 | 14 | 11 | 10 |

1 ITR: itraconazole; 2 VOR: voriconazole; 3 STRAf: Short tandem repeats Aspergillus fumigatus.

3.2. Microsatellite Typing Results and Evidence for Clonal Spread of a Single Triazole-Resistant A. fumigatus Genotype

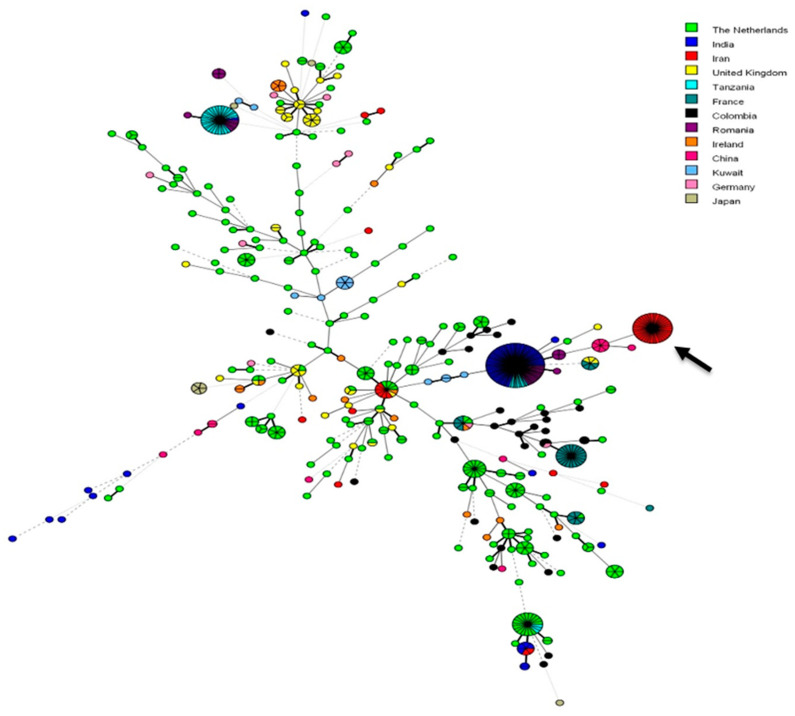

Genotypic analysis identified that 41 A. fumigatus isolates with TR34/L98H shared the same allele across all nine examined microsatellite loci. These isolates came from compost in 13 different cities. The three remaining isolates with TR34/L98H exhibited three different genotypes. The two isolates with M172V differed by five microsatellite loci (2B, 2C, 3B, 3C, 4C). From the 14 azole resistant isolates with wild type cyp51A, which originated from 5 different cities, two isolates shared the same alleles across all nine microsatellite loci, while the 12 other isolates were genetically very diverse. A minimum spanning tree (MST) based on azole-resistant strains from various countries showed that the 41 Iranian A. fumigatus isolates with TR34/L98H formed a separate cluster (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Minimum-spanning tree showing the genetic relationship of resistant Aspergillus fumigatus genotypes. Iranian clonal complex is illustrated by the arrow. Solid thick and thin branches demonstrate 1 or 2 microsatellite markers difference, respectively; dashed branches indicate 3 microsatellite markers difference between two genotypes; 4 or more microsatellite markers difference between genotypes are demonstrated with dotted branches.

4. Discussion

In this study, about 70% A. fumigatus isolates from compost samples grew on SDA supplemented with azoles and had the TR34/L98H mutation in the cyp51A gene. Indeed, the high rate of resistance to azole drugs due to the TR34/L98H mutation in A. fumigatus in Iran outperforms previous studies done during 2013–2016. The prevalence of clinical or environmental azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates harboring this mutation was much lower in a previous episode and has been estimated between 3.2–6.6% [16,18,31]. Concurrent genetic studies of worldwide A. fumigatus isolates harboring the TR34/L98H resistance mechanism also suggested clonal expansion from a common resistant ancestor [32,33]. In the current study the azole resistant A. fumigatus population with TR34/L98H was grouped into four microsatellite genotypes, in which the genotype with STRAf profile: 2A:22, 2B:10, 2C:9, 3A:9, 3B:9, 3C:23, 4A:8, 4B:10, 4C:8 included 41 (93%) identical isolates, showing clonal expansion across different geographic locations. Furthermore, MST showed Iranian A. fumigatus isolates harboring TR34/L98H were apart from isolates of other countries and previously recovered Iranian isolates. Similar to our finding, Chowdhary et al. described a clonal spread and emergence of environmental azole resistant A. fumigatus strains carrying the TR34/L98H mutation from different parts of India. All Indian azole resistant isolates shared the same multilocus microsatellite genotype not found in any other analyzed samples within India or from other Asian or European countries [14]. In agreement with our findings, there is strong evidence that azole-susceptible or cyp51A single point mutation resistance strains have a greater genetic diversity than isolates harboring TR34/L98H and TR46/Y121F/T289A mutations, since the expansion of latter strains at a local level is predominantly clonal [14,34,35,36]. The dispersal of A. fumigatus with the TR34/L98H genotype supports the hypothesis that these strains have robust fitness in natural environments, with comparable or even higher fitness than that of wild-type strains [11]. Clonal spread of a single genotype in our study reinforced the hypothesis that geographic distances are not a barrier for the global spread from its centers of origin and their ability to cover thousands of miles by producing a large number of airborne spores or by anthropogenic means [14,31,37,38,39]. The widespread application of azole fungicides in Iran could have contributed to the spread of azole resistant A. fumigatus in environment niches, such as compost. To mitigate spread of azole resistant A. fumigatus in environment, changing of practices to prevent fungal diseases in plants on the fields is necessary. Procedures, such as prudent and restricted use of fungicides, controlling doses, and periods of fungicide application could be helpful. In cases where resistance to fungicides is observed, either the dosage can be increased or alternative fungicides can be used. In addition, environmental surveillance studies aimed to collect precise information of azole resistance monitoring to investigate the size and impact of this emerging problem is necessary [40].

Interestingly, we found that a sizable number of isolates (8 out of 54 resistant isolates) with azole MICs ≥16 mg/L exhibited no mutations in cyp51A. Other mechanisms of resistance, such as increased production of drug target Cyp51A protein, multidrug efflux pumps, or other proposed but not yet fully characterized mechanisms of resistance, such as amino acid substitutions in 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA, stress response, and biofilm formation, can contribute to azole resistance in these isolates [32]. The limitation of our study was the absence of STRAf profiles of TR34/L98H A. fumigatus from neighbor countries of Iran, such as Pakistan or Turkey, for comparison with Iranian isolates [41,42]. In addition, the absence of clinical A. fumigatus was another drawback of our study. As most clinical microbiology laboratories in Iran do not routinely perform antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus, the prevalence of azole resistance and mechanism of resistance in clinical A. fumigatus isolates in Iran is unknown [17].

5. Conclusions

Clonal spread of triazole resistant A. fumigatus isolated from compost, which is used widely in gardens and indoor plants in Iran, is concerning. This study highlights the importance of antifungal resistance surveillance studies of clinical and environmental Aspergillus isolates in Iran.

Acknowledgments

F.A. is a recipient of an ESCMID observership grant to visit ESCMID observership center 58 (CWZ, Nijmegen, The Netherlands).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A., H.B. and J.F.M.; Data curation, F.A., K.A., M.N. and S.K.; Formal analysis, F.A. and T.d.G.; Funding acquisition, J.F.M.; Investigation, K.A. and T.d.G.; Methodology, T.d.G.; Supervision, J.F.M.; Writing—original draft, F.A., H.B., and J.F.M.; Writing—review and editing, K.A., M.N., S.K. and T.d.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by National Institutes for Medical Research Development (NIMAD), Grant/Award Number: 982677 and Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran, Grant/Award Number: 1352.

Conflicts of Interest

J.F.M. received grants from Pulmozyme and F2G. He has been a consultant to Scynexis and received speaker’s fees from United Medical, TEVA, and Gilead Sciences. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Meis J.F., Chowdhary A., Rhodes J.L., Fisher M.C., Verweij P.E. Clinical implications of globally emerging azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016;371:20150460. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ullmann A.J., Aguado J.M., Arikan-Akdagli S., Denning D.W., Groll A.H., Lagrou K., Lass-Flörl C., Lewis R.E., Munoz P., Verweij P.E., et al. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: Executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018;24(Suppl. 1):e1–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh A., Sharma B., Mahto K.K., Meis J.F., Chowdhary A. High-Frequency Direct Detection of Triazole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus from Patients with Chronic Pulmonary Fungal Diseases in India. J. Fungi. 2020;6:67. doi: 10.3390/jof6020067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verweij P.E., Chowdhary A., Melchers W.J., Meis J.F. Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: Can We Retain the Clinical Use of Mold-Active Antifungal Azoles? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;62:362–368. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klaassen C.H., Gibbons J.G., Fedorova N.D., Meis J.F., Rokas A. Evidence for genetic differentiation and variable recombination rates among Dutch populations of the opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol. Ecol. 2012;21:57–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivero-Menendez O., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Mellado E., Cuenca-Estrella M. Triazole Resistance in Aspergillus spp.: A Worldwide Problem? J. Fungi. 2016;2:21. doi: 10.3390/jof2030021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lestrade P.P.A., Meis J.F., Melchers W.J.G., Verweij P.E. Triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: Recent insights and challenges for patient management. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resendiz-Sharpe A., Mercier T., Lestrade P.P.A., van der Beek M.T., von dem Borne P.A., Cornelissen J.J., De Kort E., Rijnders B.J.A., Schauwvlieghe A.F.A.D., Verweij P.E., et al. Prevalence of voriconazole-resistant invasive aspergillosis and its impact on mortality in haematology patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019;74:2759–2766. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buil J.B., Hagen F., Chowdhary A., Verweij P.E., Meis J.F. Itraconazole, Voriconazole, and Posaconazole CLSI MIC Distributions for Wild-Type and Azole-Resistant Aspergillus fumigatus Isolates. J. Fungi. 2018;4:103. doi: 10.3390/jof4030103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J., Snelders E., Zwaan B.J., Schoustra S.E., Meis J.F., van Dijk K., Hagen F., van der Beek M., Kampinga G.A., Zoll J., et al. A Novel Environmental Azole Resistance Mutation in Aspergillus fumigatus and a Possible Role of Sexual Reproduction in Its Emergence. mBio. 2017;8:e00791-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00791-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chowdhary A., Meis J.F. Emergence of azole resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and One Health: Time to implement environmental stewardship. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;20:1299–1301. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trovato L., Scalia G., Domina M., Oliveri S. Environmental Isolates of Multi-Azole-Resistant Aspergillus spp. in Southern Italy. J. Fungi. 2018;4:131. doi: 10.3390/jof4040131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhary A., Kathuria S., Xu J., Meis J.F. Emergence of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains due to agricultural azole use creates an increasing threat to human health. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003633. doi: 10.1371/annotation/4ffcf1da-b180-4149-834c-9c723c5dbf9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chowdhary A., Kathuria S., Xu J., Sharma C., Sundar G., Singh P.K., Gaur S.H.N., Hagen F., Klaassen C.H., Meis J.F. Clonal expansion and emergence of environmental multiple-triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR₃₄/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in India. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiederhold N.P., Verweij P.E. Aspergillus fumigatus and pan-azole resistance: Who should be concerned? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2020;33:290–297. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badali H., Vaezi A., Haghani I., Yazdanparast S.A., Hedayati M.T., Mousavi B., Ansari S., Hagen F., Meis J.F., Chowdhary A. Environmental study of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus with TR34/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in Iran. Mycoses. 2013;56:659–663. doi: 10.1111/myc.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahangarkani F., Puts Y., Nabili M., Khodavaisy S., Moazeni M., Salehi Z., Laal Kargar M., Badali H., Meis J.F. First azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolates with the environmental TR46 /Y121F/T289A mutation in Iran. Mycoses. 2020;63:430–436. doi: 10.1111/myc.13064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seyedmousavi S., Hashemi S.J., Zibafar E., Zoll J., Hedayati M.T., Mouton J.W., Melchers W.J.G., Verweij P.E. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus, Iran. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:832–834. doi: 10.3201/eid1905.130075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoustra S.E., Debets A.J.M., Rijs A.J.M.M., Zhang J., Snelders E., Leendertse P.C., Melchers W.J.G., Rietveld A.G., Zwaan B.J., Verweij P.E. Environmental Hotspots for Azole Resistance Selection of Aspergillus fumigatus, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019;25:1347–1353. doi: 10.3201/eid2507.181625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sewell T.R., Zhang Y., Brackin A.P., Shelton J.M.G., Rhodes J., Fisher M.C. Elevated Prevalence of Azole-Resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in Urban versus Rural Environments in the United Kingdom. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e00548-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00548-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaezi A., Fakhim H., Javidnia J., Khodavaisy S., Abtahian Z., Vojoodi M., Nourbakhsh F., Badali H. Pesticide behavior in paddy fields and development of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus: Should we be concerned? J. Mycol. Med. 2018;28:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanni A., Fontana F., Gamberini R., Calabria A. Occurrence of dicarboximide fungicides and their metabolites’ residues in commercial compost. Agronomie. 2004;24:7–12. doi: 10.1051/agro:2003058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camps S.M., Rijs A.J., Klaassen C.H., Meis J.F., O’Gorman C.M., Dyer P.S., Melchers W.J., Verweij P.E. Molecular epidemiology of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates harboring the TR34/L98H azole resistance mechanism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:2674–2680. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00335-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chowdhary A., Sharma C., Kathuria S., Hagen F., Meis J.F. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus with the environmental TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation in India. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014;69:555–557. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi. Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute; Wayne, PA, USA: 2017. CLSI standard M38. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klaassen C.H., de Valk H.A., Curfs-Breuker I.M., Meis J.F. Novel mixed-format real-time PCR assay to detect mutations conferring resistance to triazoles in Aspergillus fumigatus and prevalence of multi-triazole resistance among clinical isolates in the Netherlands. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:901–905. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavergne R.A., Morio F., Favennec L., Dominique S., Meis J.F., Gargala G., Verweij P.E., Le Pape P. First description of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus due to TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4331–4335. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00127-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Valk H.A., Meis J.F., Curfs I.M., Muehlethaler K., Mouton J.W., Klaassen C.H. Use of a novel panel of nine short tandem repeats for exact and high-resolution fingerprinting of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:4112–4120. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4112-4120.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balajee S.A., de Valk H.A., Lasker B.A., Meis J.F., Klaassen C.H.W. Utility of a microsatellite assay for identifying clonally related outbreak isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2008;73:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guinea J., García de Viedma D., Peláez T., Escribano P., Muñoz P., Meis J.F., Klaassen C.H.W., Bouza E. Molecular epidemiology of Aspergillus fumigatus: An in-depth genotypic analysis of isolates involved in an outbreak of invasive aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:3498–3503. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01159-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nabili M., Shokohi T., Moazeni M., Khodavaisy S., Aliyali M., Badiee P., Zarrinfar H., Hagen F., Badali H. High prevalence of clinical and environmental triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in Iran: Is it a challenging issue? J. Med. Microbiol. 2016;65:468–475. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chowdhary A., Sharma C., Meis J.F. Azole-resistant aspergillosis: Epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, and treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;216(suppl. 3):S436–S444. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonçalves S.S. Global Aspects of Triazole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus with Focus on Latin American Countries. J. Fungi. 2017;3:5. doi: 10.3390/jof3010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdolrasouli A., Rhodes J., Beale M.A., Hagen F., Rogers T.R., Chowdhary A., Meis J.F., Armstrong-James D., Fisher M.C. Genomic Context of Azole Resistance Mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus Determined Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. mBio. 2015;6:e00939. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00536-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Rubio R., Escribano P., Gomez A., Guinea J., Mellado E. Comparison of Two Highly Discriminatory Typing Methods to Analyze Aspergillus fumigatus Azole Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1626. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashu E.E., Hagen F., Chowdhary A., Meis J.F., Xu J. Global Population Genetic Analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus. mSphere. 2017;2:e00019-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00019-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakano Y., Tashiro M., Urano R., Kikuchi M., Ito N., Moriya E., Shirahige T., Mishima M., Takazono T., Miyazaki T., et al. Characteristics of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus attached to agricultural products imported to Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020;26:1021–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunne K., Hagen F., Pomeroy N., Meis J.F., Rogers T.R. Intercountry transfer of triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus on plant bulbs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017;65:147–149. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen R.H., Hagen F., Astvad K.M., Tyron A., Meis J.F., Arendrup M.C. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in Denmark: A laboratory-based study on resistance mechanisms and genotypes. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016;22:570-e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berger S., El Chazli Y., Babu A.F., Coste A.T. Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: A Consequence of Antifungal Use in Agriculture? Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1024. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Özmerdiven G.E., Ak S., Ener B., Ağca H., Cilo B.D., Tunca B., Akalın H. First determination of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR34/L98H mutations in Turkey. J. Infect. Chemother. 2015;21:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perveen I., Sehar S., Naz I., Ahmed S. Prospective evaluation of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates in Pakistan; Proceedings of the 7th Advances Against Aspergillosis; Manchester, UK. 3–5 March 2016. [Google Scholar]