Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Medicare beneficiaries recovering from a critical illness are increasingly being discharged home instead of to post-acute care facilities. Rehabilitation services are commonly recommended for ICU survivors, however little is known about the frequency and dose of home-based rehabilitation in this population.

Design:

Retrospective analysis of 2012 Medicare hospital and home health (HH) claims data, linked with assessment data from the Medicare Outcomes and Information Set (OASIS).

Setting:

Participant homes

Participants:

Medicare beneficiaries recovering from an ICU stay>24 hours, who were discharged directly home with HH services within 7 days of discharge, and survived without readmission or hospice transfer for at least 30 days (n=3176).

Intervention:

None

Measurements:

Count of rehabilitation visits received during HH care episode

Results:

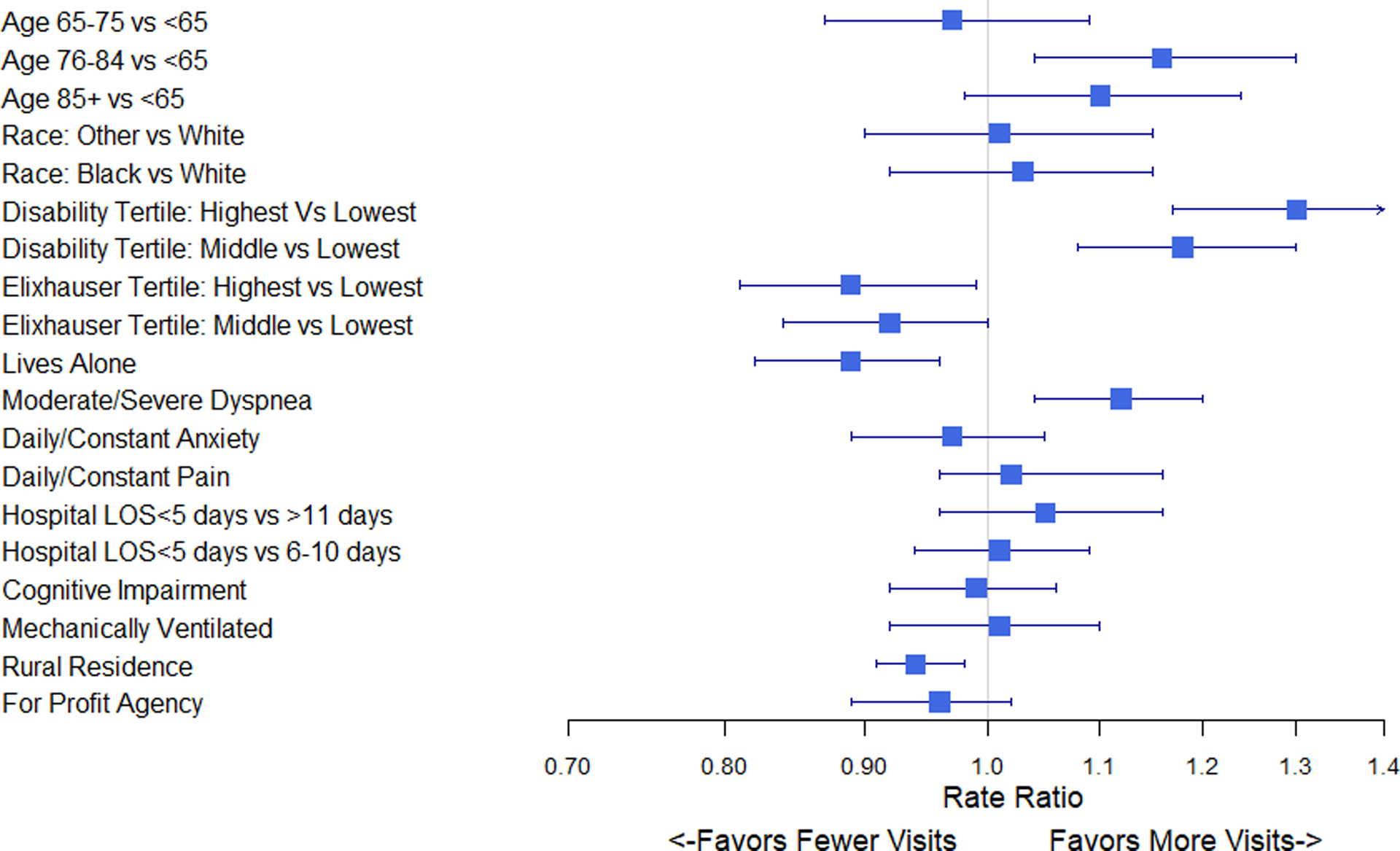

A total of 19564 rehabilitation visits were delivered to ICU survivors over 118,145 person-days in HH settings—a rate of 1.16 visits per week. One third of ICU survivors received no rehabilitation visits during HH care. In adjusted models, those with the highest baseline disability received 30% more visits (RR=1.30, 95% CI: 1.17–1.45) than those with the least disability. Conversely, there was an inverse relationship between multimorbidity (Elixhauser scores) and count of rehabilitation visits received; those with the highest tertile of Elixhauser scores received 11% fewer visits (RR=0.89, 95% CI: 0.81–0.99) than those in the lowest tertile. Participants living in a rural setting (versus urban) received 6% fewer visits (RR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.91–0.98) and those who lived alone received 11% fewer visits (RR=0.89, 95% CI 0.82–0.96) than those who lived with others.

Conclusion:

On average, Medicare beneficiaries discharged home after a critical illness receive few rehabilitation visits in the early post-hospitalization period. Those who had more comorbidities, who lived alone, or who lived in rural settings received even fewer visits, suggesting a need for their consideration during discharge planning.

INTRODUCTION

Skilled physical, occupational, and speech therapy services (collectively, rehabilitation therapies) are an integral part of the medical care that Medicare beneficiaries (generally, those 65 years and older) receive during an ICU stay.1 Yet, functional deficits that occur as a result of ICU stays are often unresolved at hospital discharge,2–4 suggesting that ongoing rehabilitation after hospital discharge is necessary to optimize recovery.5 Functional recovery after an ICU stay often takes 3–6 months, and still almost half of older survivors are unable to regain their prior level of function.2 Participation in post-hospital rehabilitation is strongly recommended to improve functional recovery,6 but it is unclear how frequently older survivors of critical illness receive these services after hospital discharge.

Increasingly, ICU survivors are discharging home instead of to post-acute care facilities7, despite high levels of disability and mobility impairment that hamper participation in rehabilitation.8 High disability contributes to nearly 25% of survivors requiring home health (HH) care services after discharge.7,9 Patients receiving HH are generally assessed by a registered nurse, and then subsequently can receive any combination of nursing care, skilled rehabilitation services, and social work services deemed necessary for recovery with 100% coverage from Medicare.10 However, little is known about the number of rehabilitation visits received by older ICU survivors in HH programs and what factors are associated with use of rehabilitation. Addressing this knowledge gap may identify populations for whom rehabilitation care needs to be targeted.11

Our primary objective was to characterize the number of rehabilitation visits received by older ICU survivors in home health rehabilitation programs. Our secondary objective was to evaluate factors associated with the number of rehabilitation visits received among ICU survivors who utilize HH.

METHODS

This was a retrospective analysis of the 2012 Medicare 5% claims file for HH users, which was subsequently linked to the Medicare Outcomes and Assessment Information (OASIS) file, the MEDPAR file, and the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. Briefly, the HH claims file includes billing and payment information (including rehabilitation service use); the OASIS file includes comprehensive patient assessment data from face-to-face patient interviews conducted in the home within 48 hours of hospital discharge and at the time of patient discharge, death, or transfer to institutional facilities or hospice. The MEDPAR file includes details from the index hospitalization, including procedures, comorbidities, and length of stay in the hospital and ICU, as well as post-acute care claims for skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), and long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs). Detailed beneficiary sociodemographic information, including Medicaid dual eligibility and county of residence, were extracted from the Master Beneficiary Summary File. Lastly, the Medicare Provider of Services (POS) file was used to extract ownership and geographic information about the home health agency treating each patient.

Using our database of Medicare beneficiaries using HH services, we identified those who initiated HH services in the United States (excluding US territories such as Puerto Rico) within 7 days of an acute hospitalization with a nested ICU stay of >24 hours. We excluded those who had MEDPAR claims for institutional post-acute care services (SNF, IRF, or LTACH) prior to initiating home health care. We also excluded patients who received care in a psychiatric or intermediate ICU, or who were readmitted, transferred to hospice, or deceased within 30 days of discharge (Supplemental Figure S1). This project was completed with IRB approval from the University of Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of the study was the number of rehabilitation visits received per patient within the first home health episode of care (up to 60 days). We calculated rehabilitation visits by extracting individual revenue codes associated with physical therapy (042x), occupational therapy (043x), and speech therapy (044x) from the HH claims file, and summing the total count of visits delivered.

Candidate Variables

Candidate variables from 4 main domains were selected for inclusion in our models based on the judgement of an expert geriatrician (TMG), critical care physician (LEF), and HH physical therapist (JRF). These domains were patient sociodemographic characteristics, post-hospital disability, medical complexity, and symptom burden. While higher disability is a primary reason in current home health payment models to engage rehabilitation services, multiple studies have shown that home care service delivery varies across Census bureau regions.12–14 From a clinical perspective, higher medical complexity and symptom burden (such as pain) may limit participation in rehabilitation. We also accounted for agency ownership in the models.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Patient age, race, Census Bureau geographic region, Medicaid dual eligibility, and gender were extracted from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. Age was categorized as <65 years old (i.e. disability entitlement to Medicare), 65–75 years old, 76–84 years old, or more than 85 years old. We categorized the patient as living alone vs living with either a caregiver or in a congregate living situation (i.e. assisted living facility). We also captured whether a patient resided in a rural area (vs urban) by mapping the patient’s state and county code of residence to Medicare’s Core-Based Statistical Areas (from 2012). To control for potential differences in home health care availability, we also used the POS file linked with publicly available 2012 Census population data to summarize the number of home health agencies per 100,000 at the county-level.

Post-Hospital Disability:

At the first HH visit after hospital discharge, functional status on 8 ADL tasks (upper and lower body dressing, bathing, transfers, ambulation, toileting and toileting hygiene, and grooming) was captured on the Medicare OASIS, and scored as either 0 (independent), 1 (requires minor human assistance or an assistive device), or 2 (totally dependent or unable to perform the task). The sum OASIS disability score was calculated for each patient on a 0–16 scale.

Medical Complexity

Total hospital and ICU length of stay were extracted from the MEDPAR file, and time spent under the care of the HH agency was extracted from the OASIS file. A dichotomous variable for whether or not an older adult was mechanically ventilated was created based on the presence or absence of the associated ICD-9 procedure code (96.7x).15 Multimorbidity was assessed using the Elixhauser Comorbidity index, which was calculated using a validated algorithm from ICD-9 codes on the acute hospitalization claim.16 Because there are no psychometrically validated measures of cognition on the OASIS, cognitive impairment was categorized dichotomously for this study as whether or not an older adult required human assistance for management of daily activities in the home due to cognitive dysfunction, as assessed by the evaluating therapist.

Symptom Burden

We assessed symptom burden from the OASIS assessment, focusing on three key symptoms that may impact participation in rehabilitation: dyspnea (5-item OASIS question M1400), anxiety (5-item OASIS question M1720), and pain (5-item OASIS question M1242). For dyspnea, the OASIS question prompts clinicians to record when the patient is dyspneic or noticeably short of breath—moderate to severe dyspnea was categorized as dyspnea that occurs with light activity (such as talking; score 3/4) or at rest (score 4/4). For the OASIS pain item, the frequency of activity-limiting pain was dichotomized as occurring daily (score 3/4) or constantly (score 4/4) versus never or less than daily. For anxiety, OASIS item M1720 asks clinicians to record how frequently the patient is anxious—patients were considered to have daily/constant anxiety if episodes of anxiety reported by the patient occurred daily (score of 3/4) or all of the time (score of 4/4).

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R software version 1.1.463 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Sample demographics were assessed for all HH participants in the analytic sample, and the proportions of HH users who used rehabilitation services was calculated. We then evaluated the distribution of total rehabilitation visits across the initial 60-day episode of HH care. Next, we modeled the bivariate association of each candidate variable on episode rehabilitation visits using a zero-inflated negative binomial regression model, with a log link function with offset set as the natural logarithm of HH length of stay. A zero-inflated negative binomial model was chosen to account for the high number of older adults who received no rehabilitation visits and for the over-dispersion of the count data. Lastly, a multivariable model, controlling for all candidate variables, was calculated. For both bivariate and multivariable models, rate ratios (RR) for each candidate variable, showing the proportional difference in the number of rehabilitation visits for each level of the variable, were estimated. A RR less than 1 indicates that a candidate variable was associated with fewer rehabilitation visits than the reference category, and a RR greater than 1 indicates a greater utilization of rehabilitation. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p-value <0.05.

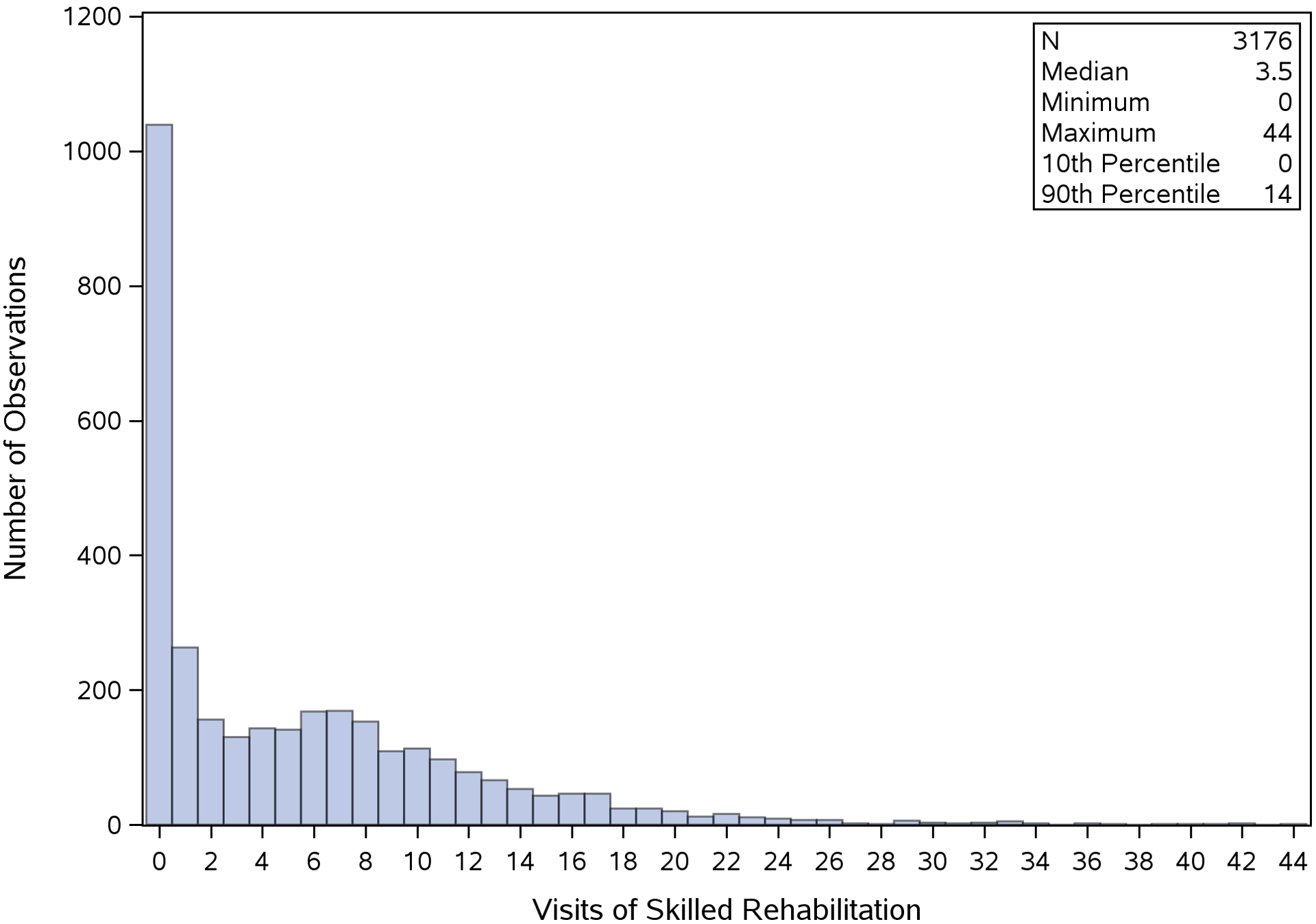

RESULTS

A majority of the 3176 patients in the sample were female and white, and most lived in urban settings (Table 1). Patients started home health care within a median (interquartile range) of 1 (1–2) days after hospital discharge. Overall, 2137 (67%) older adult ICU survivors received 1 or more home rehabilitation visits after hospital discharge. A total of 19,564 rehabilitation visits were delivered over 118,145 person-days in home health settings—averaging 1.16 visits per 7 days. The median (interquartile range) length of stay in home health care was 30 (19–50) days. There was also significant variability in the use of rehabilitation observed among ICU survivors (Figure 1). A total of 2075 survivors (65.3%) received physical therapy, 729 (22.9%) received occupational therapy and 144 (4.5%) received speech therapy. Of the 2137 rehabilitation users (1+ visit from any discipline), 1413 (66%) patients received care from only a single rehabilitation discipline, 637 (30%) from 2 disciplines, and 87 (4%) received care from all 3 rehabilitation disciplines.

Table 1:

Sample Demographics of ICU Survivors Discharged to Home Health Care

| Variable | Total Sample (n=3176) |

|---|---|

| Age, n(%) | |

| <65 years | 482 (15.2) |

| 65–75 years | 1108 (35.0) |

| 76–84 years | 977 (30.8) |

| >85 years | 609 (19.2) |

| Race, n(%) | |

| Black | 309 (9.7) |

| White | 2612 (82.2) |

| Other | 255 (8.0) |

| Medicaid Beneficiary, n(%) | 709 (22.3) |

| Lives Alone, n(%) | 606 (19.0) |

| Rural Residence, n(%)* | 772 (24.3) |

| US Census Region, n(%) | |

| New England | 181 (5.7) |

| Mid Atlantic | 484 (15.2) |

| South Atlantic | 803 (25.2) |

| East South Central | 256 (8.1) |

| West South Central | 308 (9.7) |

| East North Central | 522 (16.4) |

| West North Central | 193 (6.1) |

| Pacific | 291 (9.2) |

| Mountain | 138 (4.4) |

| Elixhauser Score, n(%) | |

| 0–2 | 516 (16.3) |

| 3–5 | 1695 (53.4) |

| 6+ | 965 (30.4) |

| Hospital Length of Stay | |

| 0–5 days | 1056 (33.3) |

| 6–10 days | 1470 (46.3) |

| 11+ days | 650 (20.5) |

| Mechanically Ventilated, n(%) | 466 (14.7) |

| ADL Disability Score, n(%)† | |

| 5/16 or lower | 767 (24.2) |

| 6/16 to 9/16 | 1763 (55.5) |

| 10/16 or higher | 646 (20.3) |

| Cognitive Impairment, n(%)‡ | 1151 (36.2) |

| Moderate/Severe Dyspnea, n(%)§ | 811 (25.5) |

| Daily/Constant Anxiety, n(%)‖ | 602 (19.0) |

| Daily/Constant Pain, n(%)¶ | 1814 (57.1) |

Rural/Urban status was determined by 2012 Medicare core-based statistical areas

Post-hospital disability on 8 ADL tasks (upper and lower body dressing, bathing, transfers, ambulation, toileting and toileting hygiene, and grooming) scored at initial HH assessment as either 0 (independent), 1 (requires minor human assistance or an assistive device), or 2 (totally dependent or unable to perform the task). The sum disability score was calculated for each patient on a 0–16 scale

From the Medicare Outcomes Assessment and Information Set item M1700 (0–4 scale). Scores 1–4 indicate requirement for human assistance due to cognitive impairment

From the Medicare Outcomes Assessment and Information Set item M1400 (0–4 scale). Scores of 3–4 indicate dyspnea occurs with light activity or at rest.

From the Medicare Outcomes Assessment and Information Set item M1420 (0–3 scale). Scores of 2–3 indicate presence of daily or constant anxiety

From the Medicare Outcomes Assessment and Information Set item M1242 (0–4 scale). Scores of 3–4 indicate activity-limiting pain occurs daily or constantly.

FIGURE 1:

Distribution of rehabilitation visits over the first episode of home health for 3176 Medicare beneficiaries who survived an ICU stay and discharged directly home

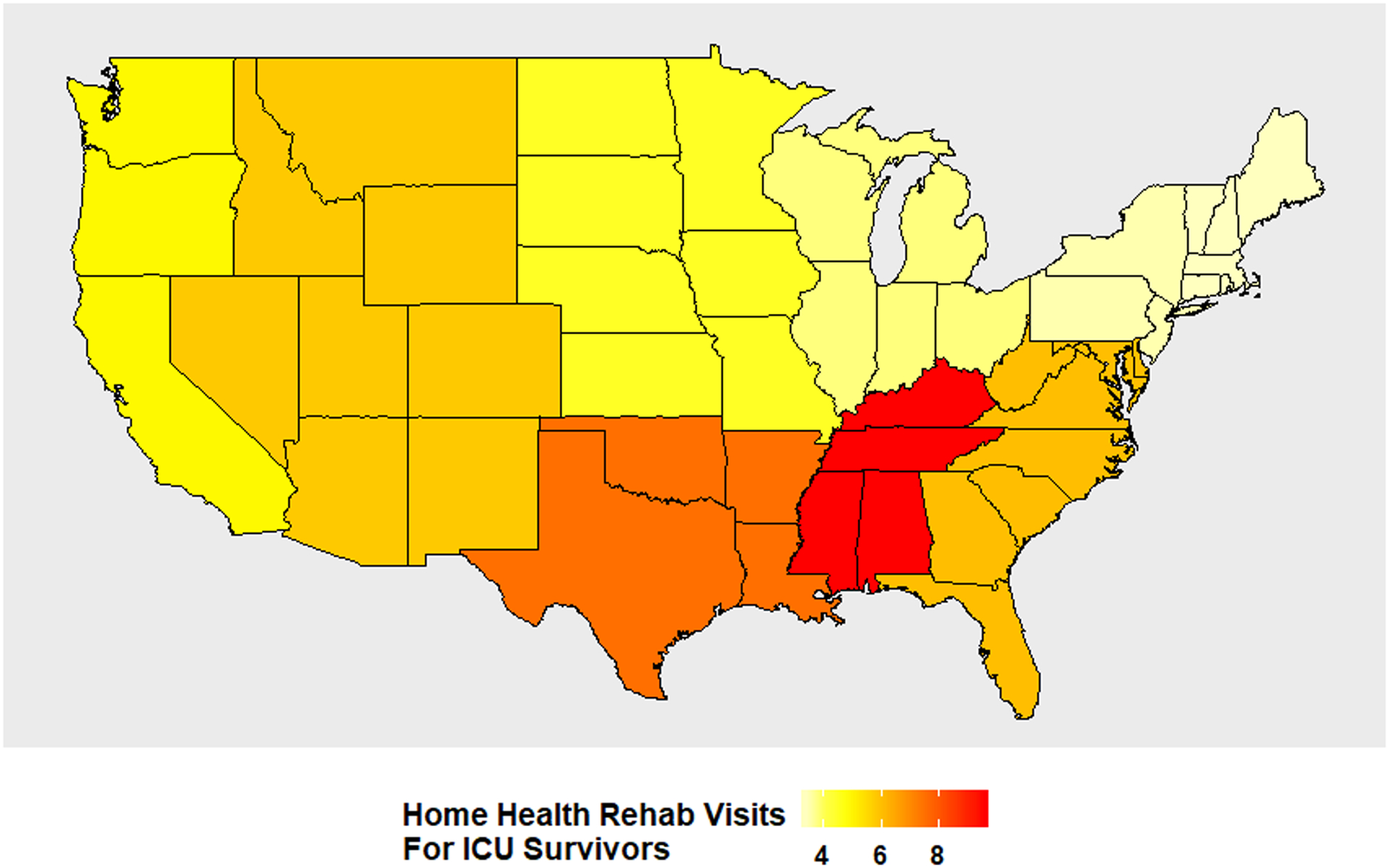

In bivariate analysis, older age and higher OASIS disability scores were associated with higher use of rehabilitation services. Conversely, higher Elixhauser score, living alone, living in a rural area, and Medicaid dual eligibility were all associated with lower rehabilitation use. Symptom burden (anxiety, pain, or dyspnea), mechanical ventilation, patient race, and cognitive impairment were not significantly associated with rehabilitation utilization in bivariate analysis (Table 2). There was also significant geographic variability observed across Census Bureau regions (Figure 2), with nearly 3-fold differences between the region with the highest number of rehabilitation visits (East South Central; 9.6 visits per episode) and the region with the lowest number of visits (New England; 3.4 visits/episode).

Table 2:

Unadjusted Variable Associations with Rehabilitation Visit Count

| Variable | Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <65 years old | REF |

| <76 years | 0.99 (0.89–1.11) |

| 76–84 years | 1.20 (1.08–1.34) |

| >85 years | 1.14 (1.02–1.27) |

| Race | |

| White | REF |

| Black | 1.06 (0.95–1.18) |

| Other | 1.02 (0.90–1.14) |

| Medicaid Beneficiary | 0.90 (0.83–0.97) |

| Lives Alone | 0.85 (0.78–0.93) |

| Rural Residence | 0.90 (0.84–0.98) |

| Elixhauser Score | |

| 0–2 | REF |

| 3–5 | 0.95 (0.86–1.04) |

| 6+ | 0.93 (0.83–1.02) |

| Hospital Length of Stay | |

| 0–5 days | REF |

| 6–10 days | 1.00 (0.93–1.09) |

| 11+ days | 1.07 (0.97–1.17) |

| Mechanically Ventilated | 0.99 (0.91–1.09) |

| ADL Disability Score† | |

| 5/16 or lower | REF |

| 6/16 to 9/16 | 1.20 (1.10–1.32) |

| 10/16 or higher | 1.34 (1.20–1.49) |

| Cognitive Impairment‡ | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) |

| Moderate/Severe Dyspnea§ | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) |

| Daily/Constant Anxiety‖ | 0.98 (0.90–1.07) |

| Daily/Constant Pain¶ | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) |

| For Profit Agency | 0.90 (0.97–1.04) |

| Agencies per 100K population (county-level) | |

| Lowest Tertile | REF |

| Middle Tertile | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) |

| Highest Tertile | 1.02 (0.94–1.12) |

CI=Confidence Interval; ADL=activities of daily living; ICU=intensive care unit; LOS=length of stay

Post-hospital disability on 8 ADL tasks (upper and lower body dressing, bathing, transfers, ambulation, toileting and toileting hygiene, and grooming) scored at initial HH assessment as either 0 (independent), 1 (requires minor human assistance or an assistive device), or 2 (totally dependent or unable to perform the task). The sum disability score was calculated for each patient on a 0–16 scale

From the Medicare Outcomes Assessment and Information Set item M1700 (0–4 scale). Scores 1–4 indicate requirement for human assistance due to cognitive impairment

From the Medicare Outcomes Assessment and Information Set item M1400 (0–4 scale). Scores of 3–4 indicate significant dyspnea occurs with light activity or at rest.

From the Medicare Outcomes Assessment and Information Set item M1420 (0–3 scale). Scores of 2–3 indicate presence of daily or constant anxiety

From the Medicare Outcomes Assessment and Information Set item M1242 (0–4 scale). Scores of 3–4 indicate activity-limiting pain occurs daily or constantly.

FIGURE 2:

Unadjusted count of rehabilitation visits per home health episode for Medicare beneficiaries who survived an ICU stay and discharged directly home, presented by Census Bureau region.

In the fully adjusted multivariable models (Figure 3), older age and higher post-hospital disability scores continued to be associated with receiving more rehabilitation visits. Compared to those younger than 65, patients aged 65–75 received 16% (RR=1.16, 95% CI 1.04–1.30) more rehabilitation visits and those aged older than 85 years received 10% (RR=1.10, 95% CI 0.98–1.24) more. Those in the highest tertile of post-hospital disability received 30% (RR=1.30, 95% CI 1.17–1.46) more visits relative to the lowest tertile. The presence of moderate to severe dyspnea was also associated with receiving 12% (RR=1.12, 95% CI: 1.04–1.20) more rehabilitation visits in the multivariable model. Conversely, living alone was associated with receiving 11% fewer visits (RR=0.89, 95% CI 0.82–0.96), and living in a rural area was associated with receiving 6% (RR=0.94, 95% CI 0.91–0.98) fewer visits. In addition, those in the highest Elixhauser score tertile, received 11% (RR=0.89, 95%CI 0.81–0.99) fewer rehabilitation visits compared to those in the lowest tertile. Patterns of geographic variability observed in the fully adjusted model was largely consistent with bivariate results (Supplemental Figure S2), with patients in the East South Central region (Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee) predicted to receive nearly twofold the number of rehabilitation visits as compared to patients in New England.

Figure 3:

Adjusted negative binomial regression results presented as rate ratios (RRs) for the impact of each variable on rehabilitation utilization. RRs greater than 1 indicate a positive impact on number of rehabilitation visits received, and RRs less than 1 indicate a negative impact. Model was adjusted for all figure variables, and additionally for Census Bureau region and county-level count of home health agencies per 100,000 population.

DISCUSSION:

In this analysis of HH rehabilitation use among Medicare beneficiaries who survived an ICU stay, we found that only two-thirds of patients receive any skilled therapy visits immediately following hospitalization, and the average patient received only 1 visit per week. We also observed substantial geographic variability in the receipt of rehabilitation services, with both regional variability and rural/urban disparities present. Although some factors reflecting greater rehabilitation needs (advanced age, greater post-hospital disability, and higher baseline dyspnea) were associated with more rehabilitation visits, other factors indicating potential risk for adverse outcomes (living alone, having a greater number of comorbidities, and living in a rural setting) were all associated with receiving fewer rehabilitation visits. These potential disparities have significant implications for discharge planning in this vulnerable population. To our knowledge, this is the first nationally-representative study describing patterns of rehabilitation use and characteristics associated with HH rehabilitation dose received by Medicare beneficiaries who survive an ICU stay.

Importantly, ICU survivors in HH settings may be the subset of critically ill older adults most likely to respond to restorative interventions targeting physical function, i.e., sick enough to require post-acute care services after a hospitalization, yet healthy enough to be discharged directly home. Post-hospital rehabilitation is believed to be an important part of post-ICU functional recovery.5,6,11,17–19 Yet we found that 1 of every 3 critical illness survivors never receives restorative rehabilitation during their episode of home health care, and among those who do the number of rehabilitation visits is relatively small and few involve disciplines other than physical therapy. Low therapy utilization is perhaps more striking because Medicare beneficiaries receiving home health care have at least one obvious need for rehabilitation service: all are considered homebound, meaning they leave home infrequently and are unable to do so without a difficult and taxing effort. Recent data have also suggested that the high levels of new-onset disability, dysphagia, and vocal cord injury associated with intensive care unit stays are commonly observed outside the hospital setting,3,20,21 suggesting a role for rehabilitation in screening all older ICU survivors after hospital discharge. While stringent rehabilitation protocols are often followed for patients after major medical events such as hip fracture or joint replacement, no such guidelines exist for older adults recovering from an ICU stay. Loose guidelines for physical therapy goals, outcomes measures, and interventions after critical illness have been published6—yet, no concrete recommendations for rehabilitation frequency, duration, and total dose were provided. A lack of concrete guidelines may partially explain the substantial regional variability observed in our study. Clearly more evidence is needed to determine the optimal dose and mode of rehabilitation for older adult ICU survivors.

An unexpected finding was that those patients who lived alone or in rural settings received significantly fewer rehabilitation visits. In the adjusted models, an 11% reduction in therapy use was observed among those who lived alone relative to those who lived with others. Patients who live with others may receive more encouragement or support to participate in rehabilitation. Conversely it is possible that those who live alone may be viewed by HH agency staff as more functionally able than those who live with caregivers or in congregate living situations, and are subsequently offered fewer rehabilitation services. Alternatively, caregivers of older adults may provide unique insights into the nature of physical deficit and be strong advocates for rehabilitation involvement. Beyond differences based on living arrangement, rural-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries also received significantly fewer home health rehabilitation visits than comparable patients living in urban settings. This disparity has previously been observed for homebound Medicare beneficiaries recovering from total joint replacement,13 and may hint at an explanation for larger problems with access to restorative care interventions for disabled older adults in rural America.22 Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of social determinants of health that may need to be addressed in future interventions for Medicare beneficiaries discharged directly home after critical illness.

Our findings build on consensus statements from ICU survivorship stakeholder groups that physical therapy and other important post-hospital rehabilitation services are likely fragmented and underutilized in the immediate post-hospitalization period.17,18,23 This underutilization of post-hospital rehabilitation appears particularly significant for patients with the most comorbidities, a finding that needs to be explored more fully in future studies. One prior study within a large cohort of younger critical illness survivors defined a single “dose” of rehabilitation to be 6 visits, with many receiving two and 3 “doses” of rehabilitation over the course of the recovery process.24 In contrast, older ICU survivors in our cohort received around 1 visit per week of skilled rehabilitation in the early HH period—and generally only received care for 30 days. Prior data suggests that the likelihood that older ICU survivors attend outpatient rehabilitation clinics after home health ends is low.8 Indeed, the observed patient characteristics, such as multimorbidity living alone, or living in rural settings that negatively influence rehabilitation use in home health settings (where rehabilitation professionals travel to patients) are magnified when these patients are asked to physically travel to therapy clinics. Overall, low use of rehabilitation in HH likely shifts the burden of functional recovery onto informal or family caregivers; these caregivers may need to take added responsibility for engaging patients in home exercise programs or physical activity with unknown impacts on outcomes.

This study is the first to provide nationally-representative estimates of rehabilitation dose received among Medicare beneficiaries who survive an ICU stay. Another strength is the linkage of claims data with robust patient-level assessment variables from OASIS such as symptom burden that are not available in hospitalization claims. This provides the most granular assessment to date of the factors associated with utilization of rehabilitation in post-ICU settings. Our study also has limitations. First, the use of 2012 data may not reflect the most contemporary trends in practice, given shifts in the number of referrals for home care use related to the Affordable Care Act. However, while the hospital readmission reduction program had small impacts on the total number of patients referred to home health care settings this program did not have a direct impact on how much care older adults received during a home health episode of care, which is the focus of this study. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission reports indicate that the number of total visits provided to Medicare beneficiaries requiring home health care services has dropped by only 0.1 visits between 2012 and 2017 (from 16.7 to 16.6 visits) with no change in overall patient complexity.25,26 Second, of those Medicare beneficiaries who did not receive rehabilitation, it is difficult to determine whether these patients were medically unable or simply unwilling to participate. Such evaluations will need to be made in a future prospective or qualitative study. Third, these data only evaluate Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, and may not be representative of older managed Medicare beneficiaries or those with private insurance. Fourth, because of the sample size, we were unable to generate reliable estimates of county-level variability or variability at the hospital referral region level—thereby leaving our estimates of geographic variability more coarsely defined at the Census bureau region. It is therefore difficult to assess whether the factors driving higher utilization in Southern states are related to unmeasured patient factors, such as body mass index, that may be different in these regions or reflect true regional differences in care delivery. Future research with larger samples is needed to shed light on other geographic and market-level factors that may drive differences in utilization.

In summary, most older adult ICU survivors discharged home received approximately 1 visit of rehabilitation per week for the first 30 days. Rehabilitation use is highly variable across geographic regions, and significantly lower for older adults who have multiple chronic conditions, who live in rural settings, or who live alone. Future work should evaluate the optimal timing, intensity, and dose of HH rehabilitation for older ICU survivors, and investigate ways to address disparities in the quantity of HH rehabilitation received among older ICU survivors.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure S1: Development of the Analytic Sample

Supplemental Figure S2: Adjusted Geographic Variability in Home Health Rehabilitation Use

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Grant Funding: J.R.F received grant support from a Foundation for Physical Therapy Research Pipeline to Health Services Research Grant, and National Institute on Aging (NIA) training grant T32AG019134. J.R.F and J.S.L. received grant support from the Center on Health Services Training and Research (CoHSTAR) and the American Physical Therapy Association Home Health Section. J.S.L. is supported by the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center. T. E. M. is supported by the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center of the NIA [P30AG021342]. T. M. G. is the recipient of an Academic Leadership Award [K07AG043587] from the NIA. L. E. F. is supported by a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders Career Development Award in Aging from the NIA [K76AG057023].

Support for VA/CMS data provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Health Services Research and Development Services, VA Information Resource Center (Project Numbers SDR-02-237 and 98-004). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Sponsor’s Role:

The funding agencies had no role in the design, methods, recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.”

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts.

Preliminary results from this work were presented in poster form at the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Annual Meeting in Portland, OR.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Connolly B, O’Neill B, Salisbury L, Blackwood B. Physical rehabilitation interventions for adult patients during critical illness: an overview of systematic reviews. Thorax. 2016;71(10):881–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Gill TM. Factors Associated with Functional Recovery among Older Intensive Care Unit Survivors. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2016;194(3):299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Gill TM. Functional trajectories among older persons before and after critical illness. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175(4):523–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, et al. Rehabilitation Interventions for Postintensive Care Syndrome: A Systematic Review*. Critical Care Medicine. 2014;42(5):1263–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prescott HC, Angus DC. Enhancing Recovery From Sepsis: A ReviewSepsis Recovery: Recognition and Management of Long-term SequelaeSepsis Recovery: Recognition and Management of Long-term Sequelae. JAMA. 2018;319(1):62–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Major ME, Kwakman R, Kho ME, et al. Surviving critical illness: what is next? An expert consensus statement on physical rehabilitation after hospital discharge. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JT, Mikkelsen ME, Qi M, Werner RM. Trends in Post-Acute Care Use after Admissions for Sepsis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosa RG, Kochhann R, Berto P, et al. More than the tip of the iceberg: association between disabilities and inability to attend a clinic-based post-ICU follow-up and how it may impact on health inequalities. Intensive care medicine. 2018:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones TK, Fuchs BD, Small DS, et al. Post–acute care use and hospital readmission after sepsis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015;12(6):904–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villa P, Pintado MC, Luján J, et al. Functional status and quality of life in elderly intensive care unit survivors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016;64(3):536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosa RG, Ferreira GE, Viola TW, et al. Effects of post-ICU follow-up on subject outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2019;52:115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke RE, Jones CD, Coleman EA, Falvey JR, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Ginde AA. Use of post-acute care after hospital discharge in urban and rural hospitals. American journal of accountable care. 2017;5(1):16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falvey JR, Bade MJ, Forster JE, et al. Home-Health-Care Physical Therapy Improves Early Functional Recovery of Medicare Beneficiaries After Total Knee Arthroplasty. JBJS. 2018;100(20):1728–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones CD, Wald HL, Boxer RS, et al. Characteristics Associated with Home Health Care Referrals at Hospital Discharge: Results from the 2012 National Inpatient Sample. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(2):879–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerlin MP, Weissman GE, Wonneberger KA, et al. Validation of Administrative Definitions of Invasive Mechanical Ventilation across 30 Intensive Care Units. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2016;194(12):1548–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott D, Davidson JE, Harvey MA, et al. Exploring the scope of post-intensive care syndrome therapy and care: engagement of non-critical care providers and survivors in a second stakeholders meeting. Critical care medicine. 2014;42(12):2518–2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Critical care medicine. 2012;40(2):502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwakman RCH, Major ME, Dettling-Ihnenfeldt DS, Nollet F, Engelbert RHH, van der Schaaf M. Physiotherapy treatment approaches for survivors of critical illness: a proposal from a Delphi study. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2019:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinn JR, Kimura KS, Campbell BR, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute laryngeal injury after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Critical care medicine. 2019;47(12):1699–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuercher P, Moret CS, Dziewas R, Schefold JC. Dysphagia in the intensive care unit: epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical management. Critical Care. 2019;23(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosar CM, Loomer L, Ferdows NB, Trivedi AN, Panagiotou OA, Rahman M. Assessment of Rural-Urban Differences in Postacute Care Utilization and Outcomes Among Older US Adults. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(1):e1918738–e1918738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bemis-Dougherty AR, Smith JM. What Follows Survival of Critical Illness? Physical Therapists’ Management of Patients With Post–Intensive Care Syndrome. Physical Therapy. 2013;93(2):179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chao P-w, Shih C-J, Lee Y-J, et al. Association of postdischarge rehabilitation with mortality in intensive care unit survivors of sepsis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;190(9):1003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Home Health Care Services (2019 Report). Retrieved January 10th 2020 from http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar19_medpac_ch9_sec_rev.pdf..

- 26.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Home Health Care Services (2015 Report). Retrieved January 10th 2020 from http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-9-home-health-care-services-march-2015-report-.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure S1: Development of the Analytic Sample

Supplemental Figure S2: Adjusted Geographic Variability in Home Health Rehabilitation Use