Abstract

Scope:

Curcumin prevents bone loss in resorptive bone diseases and inhibits osteoclast formation, a key process driving bone loss. Curcumin circulates as an inactive glucuronide that can be deconjugated in situ by bone’s high β-glucuronidase (GUSB) content, forming the active aglycone. Because curcumin is a common remedy for musculoskeletal disease, effects of microenvironmental changes consequent to skeletal development and/or disease on bone curcumin metabolism were explored.

Methods and Results:

Across sexual/skeletal development or between sexes in C57BL/6 mice ingesting curcumin (500 mg/kg), bone curcumin metabolism and GUSB enzyme activity were unchanged, except for >2-fold higher (p < 0.05) bone curcumin-glucuronide substrate levels in immature (4–6-week-old) mice. In ovariectomized (OVX) or bone metastasis-bearing female mice, bone substrate levels were also >2-fold higher. Aglycone curcumin levels tended to increase proportional to substrate such that the majority of glucuronide distributing to bone was deconjugated, including OVX mice where GUSB decreased by 24% (p < 0.01). GUSB also catalyzed deconjugation of resveratrol and quercetin glucuronides by bone, and a requirement for the aglycones for anti-osteoclastogenic bioactivity, analogous to curcumin, was confirmed.

Conclusions:

Dietary polyphenols circulating as glucuronides may require in situ deconjugation for bone protective effects, a process influenced by bone microenvironmental changes.

Keywords: curcumin, bone, osteoporosis, osteoclast, resveratrol, quercetin, resorption

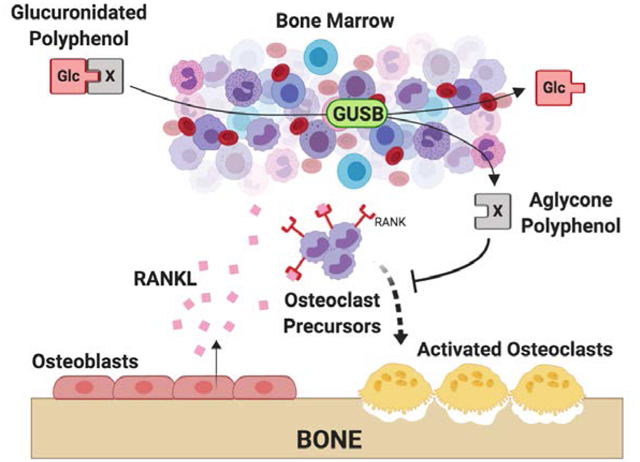

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Resorptive bone disorders are common, including age- and menopause-related bone loss, such that 40% of women and 13% of men develop osteoporotic (OP) fractures in their lifetimes[1]. Increased RANKL-stimulated differentiation of bone-resorbing osteoclasts drives bone loss in these systemic disorders, as well as in less common causes of focal osteolysis, such as joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or osteolytic bone metastases (BMETs)[2–4]. Dramatic bone milieu changes accompany and contribute to these resorptive bone disorders, including alterations in sex hormones (estrogen or testosterone) and growth factors; bone marrow adiposity and hematopoietic cell populations; and/or the accumulation of senescent cells[5–8].

Turmeric, a botanical used for millennia to treat inflammatory conditions such as arthritis, is currently a top selling herbal remedy, the majority of which are used by US adults to treat musculoskeletal disorders, with current turmeric usage reported by one third of patients with RA in a recent survey[9–13]. Clinical and/or pre-clinical in vivo studies of post-menopausal osteoporosis, RA, and osteolytic bone metastasis have repeatedly documented in vivo osteoclast-targeting effects of curcumin, the primary polyphenolic ingredient in turmeric dietary supplements[3,4,14–18]. Evidence of preserved bone mineral density, decreased biomarkers of resorptive osteoclast activity, decreased osteoclast numbers in bone, and a decreased capacity to respond to RANKL to form osteoclasts ex vivo all support in vivo osteoclast-targeted benefits of curcumin for treating a range of resorptive bone diseases, with evidence in some settings of additional indirect upstream effects, in addition to direct inhibition of RANKL-stimulated osteoclast formation and survival, via disruption of pathways or cells (e.g. senescent cells) driving RANKL-stimulated osteoclast formation[3,4,14–19].

Despite this strong in vivo evidence of curcumin anti-resorptive bioactivity and its current widespread use to treat musculoskeletal conditions, it has been an enigma how curcumin could exert bone protective effects in vivo[20]. In humans or rodents, curcumin is barely detectable in the systemic circulation due to its extensive conjugation by the intestine and liver following ingestion to form glucuronides that are thought to be inactive[17,21]. Our laboratory has recently verified a requirement for the aglycone form of curcumin for bone protective effects, confirming the previously postulated inactivity of the circulating glucuronide[17]. Critically, we also identified an enzymatic (beta-glucuronidase [GUSB]) pathway within bone that transforms curcumin-glucuronide distributing to this site following ingestion to the bioactive aglycone, and verified the GUSB-dependency of bone-specific curcumin-glucuronide metabolism, which is lost or impaired in mice with inactivating GUSB mutations leading to >75% reductions in GUSB activity. [17,21] What remains unknown, however, is whether the bioavailability and enzymatic processing of glucuronidated curcumin within bone by GUSB-expressing hematopoietic marrow cells is altered in resorptive disease states, such as osteoporosis, where, for example, sex hormones that promote GUSB expression are low and populations of hematopoietic cells, the source of GUSB within bone, shift due to changes in local growth factor levels and/or increases in marrow adiposity that accompany age and menopause-related bone loss.[8,22–31]

In vivo studies were therefore undertaken in mice with a normal GUS gene haplotype[32] to determine whether changes in the bone microenvironment that occur across the life span during sexual and skeletal development, or that accompany clinically important resorptive bone diseases (age-related bone loss, post-menopausal OP [ovariectomized mice, OVX] or focal osteolytic breast cancer BMET), alter GUSB-mediated metabolism and/or the distribution of glucuronidated curcumin in bone following curcumin ingestion. In addition, because glucuronidation of dietary polyphenols is a common in vivo metabolic fate[33,34], studies were conducted to assess the bioactivity of glucuronidated vs aglycone forms of other dietary polyphenols with reported bone protective effects (quercetin and resveratrol), and the ability of bone to deconjugate these compounds in a GUSB-specific fashion.[35–43]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Curcumin (#218580100, Fisher; 97% by weight, with assayed composition 80.6% curcumin, 13.5% demethoxycurcumin, and 2.4% bisdemethoxycurcumin) and curcumin-glucuronide were purchased, with content/purity verified using LC/MS (see method below)[21]. Resveratrol (#R150000), resveratrol-3-glucuronide (#R150015), quercetin dihydrate (#Q509500), quercetin −d3 (major) (#Q509502), and quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucuronide (#Q509510) were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals. Stock solutions were prepared in DMSO. Primary antibodies recognizing GUSB (#ARP44234_T100, Aviva Systems Biology) and β-actin (#4968, Cell Signaling Technologies [CST]) were used in Western analyses. Saccharolactone (#S0375), and 4-methylumbelliferyl-glucuronide (4-MUG; #M9130) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, and recombinant mouse receptor activator of NFκB ligand (RANKL, 462-TEC) from R&D Systems.

Animals

All procedures were approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC#: 08–149). C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson labs (#000664), with the exception of aged (18 month) male mice acquired from the National Institute on Aging (NIH). Female C57BL/6 mice underwent ovariectomy (OVX) at JAX at 24 weeks of age, with experiments performed at 32 weeks (8 weeks post-OVX), as compared to age-matched controls. Female, 4-week-old athymic Foxn1nu nude outbred mice (Envigo) were inoculated via intracardiac injection with 1×105 bone-tropic MDA-SA cells[15,17] and osteolytic lesions allowed to form in the hind legs (~3–4 weeks). Radiographic osteolytic BMET lesions were confirmed and bone-mineral density (BMD) quantified using an UltraFocus x-ray cabinet (Faxitron, Tucson, AZ).

Polyphenol Dosage Information

Mice were administered either a single or a daily dose (once a day for 7 days, or twice daily every 12 hours for 3 days) of 500 mg/kg curcumin via oral gavage, as previously described[21], a dose equivalent to 2.5 g in humans (HED), which is a relevant dose for human consumption of curcumin-enriched turmeric dietary supplements[13,44]. Ex vivo concentrations of curcumin-glucuronide, resveratrol-3-glucuronide, and quercetin-3-glucuronide examined for inhibition of osteoclastogenic activity or pharmacokinetic analyses were chosen based on reported circulating and/or bone levels (for curcumin-glucuronide) in humans and/or rodents [21,37,42,45–47].

Polyphenol Pharmacokinetic Analyses

Following in vivo dosing of curcumin as described above, blood and bone marrow (from hind legs) were obtained under isoflurane anesthesia, as previously described, at time of Cmax (30 minutes) for acute dosing and 30 minutes after the final dose for chronic dosing[21]. Regional bone metabolism of curcumin was determined by bisecting tibia from curcumin-treated mice into proximal 25% and distal 75% fractions (measured from the tibial condyle to the ankle joint) prior to isolation of bone marrow. For assay of curcumin metabolites in bone, because aglycone curcumin is irreversibly metabolized under physiologic conditions to form additional bioactive moieties, harvested bone marrow from curcumin-treated mice was briefly incubated ex vivo as previously described under conditions that “trap” (stabilize) any aglycone curcumin formed (4°C, pH5) by GUSB-mediated deconjugation of glucuronidated curcumin[21]. In separate experiments, naive bone marrow, harvested as above, was incubated with or without saccharolactone (10 mM), a GUSB inhibitor[21], prior to addition of curcumin-glucuronide (0.5 μM), resveratrol-3-glucuronide (0.5 μM), or quercetin-3-glucuronide (3 μM), with subsequent 2 hour incubation on ice and storage of supernatants at −80°C for later metabolite analyses.

LC/MS Determination of Aglycone Curcumin and Curcumin-Glucuronide

Curcumin metabolites were assayed using LC/MS as previously described (limits of detection, curcumin, 14.9 nM; curcumin-glucuronide, 2.9 nM)[21]. For bone, absolute in vivo concentrations were adjusted to the original volume of the marrow pellet (i.e., prior to dilution with pH5 sodium acetate buffer), utilizing pellet mass and assuming a tissue density of 1.06 g/ml.

LC/MS Determination of Aglycone Resveratrol and Resveratrol Metabolites

The concentrations of resveratrol and resveratrol-3-glucuronide in bone marrow samples were analyzed as previously described for analysis of plasma samples [42,43]. Briefly, aliquots of samples were acidified with concentrated HCl and treated with methanol for protein precipitation. The supernatant was dried and resuspended in 50% methanol prior to injecting an aliquot onto the LC/MS system. Chromatographic separation was achieved with reverse phase chromatography. The mass spectrometric analysis was performed using electrospray ionization operated in the negative ion mode. The analytes were detected by multiple reaction monitoring. The limit of detection for resveratrol and resveratrol-3-glucuronide was 5 nM for 100 μl sample.

LC/MS Determination of Aglycone Quercetin and Quercetin Metabolites

Bone marrow supernatants were diluted in 20 mM sodium acetate pH 5 prior to loading on 30-mg Waters HLB (hydrophilic-lipophilic balance) cartridges, washing with water, and elution with methanol. Eluates were evaporated under a stream of nitrogen and dissolved in water/acetonitrile (50:50). LC-MS analyses were performed using a Thermo Finnigan TSQ Vantage triple stage quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray interface operated in the negative ion mode. For chromatography, a Waters Symmetry Shield C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm) was eluted at room temperature with a gradient of acetonitrile in water/0.1% formic acid changed from 5% acetonitrile to 85% in 2 min and further increased to 95% in 1 min at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. The SRM transitions were for quercetin m/z 301.18 → 150.96, d3-quercetin m/z 304.12 → 150.86, quercetin-glucuronide m/z 477.37 → 300.83. (Limits of detection, quercetin, 3.5 nM; quercetin-glucuronide, 1.5 nM).

Osteoclastogenesis Assay

As previously described[21], RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with indicated aglycone or glucuronidated dietary polyphenols for 4 hours prior to induction of osteoclastogenesis by addition of RANKL (50 ng/mL, final concentration) and further incubation at 37°C for 72 hours before quantifying the number of tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-positive, multinucleated osteoclasts formed (n = 4/group).

GUSB-Specific Enzymatic Activity Assay

GUSB-specific enzyme activity in lysates of bone marrow or MDA-MB-231 cells was determined, as previously described, using standard enzymatic assay methods and a 4-methylumbelliferone [4-MU] substrate [21]. Enzymatic activity rates were normalized to bone marrow volume to compare GUSB marrow content across treatment groups [21], or to cellular protein when comparing marrow vs tumor cells.

Western Blots

GUSB protein levels were determined by immunoblot of protein lysates isolated from bone marrow or MDA-SA cells as previously described[17], with equal protein loading confirmed by visualization of total protein content, using BioRad Stain-Free labeling[17].

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (v. 6.0h, GraphPad), with values presented as mean ± SEM. Significant differences were determined by t-test or one-way/two-way ANOVA with Tukey or Sidak post-hoc test, as appropriate. For curcumin metabolites, except where indicated, pair-wise comparisons were made for 1) aglycone curcumin, and for 2) total metabolites (aglycone curcumin + glucuronidated curcumin), which is an accurate estimate of the amount of substrate available for deglucuronidation in bone at time of harvest following curcumin ingestion[21].

RESULTS

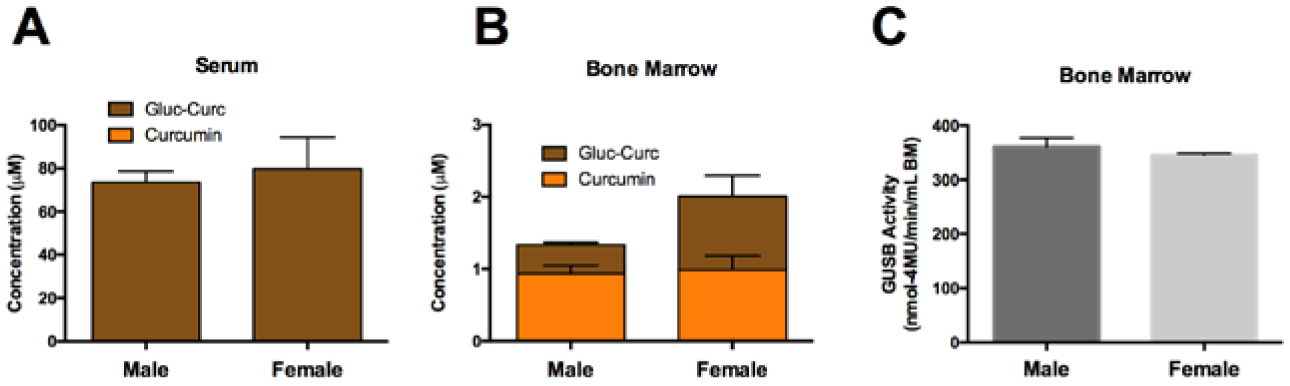

Effect of sex on curcumin metabolism in bone

In skeletally-mature 15-week old male vs female mice[48] acutely administered curcumin by oral gavage, circulating curcumin metabolites, as anticipated, were primarily curcumin-glucuronide, with serum concentrations that did not differ between sexes (Fig. 1A). While total metabolite concentrations in bone tended to be higher in female mice, reflecting higher curcumin-glucuronide substrate levels in bone at time of harvest, this difference was not statistically significant and levels of aglycone curcumin formed during ex vivo incubation were identical between sexes (Fig. 1B). Consistent with these findings, GUSB activity in bone also did not differ between the sexes (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. The effect of sex on bone marrow GUSB activity and curcumin metabolism.

Curcumin metabolism in A) serum and B) bone marrow of (15-week) male and female C57BL/6J mice (n=4–10/group), 30 minutes following oral gavage with 500 mg/kg curcumin. C) β-glucuronidase (GUSB) enzyme activity in 15-week C57BL/6J mice bone marrow (n=4–10/group). No significance differences were found.

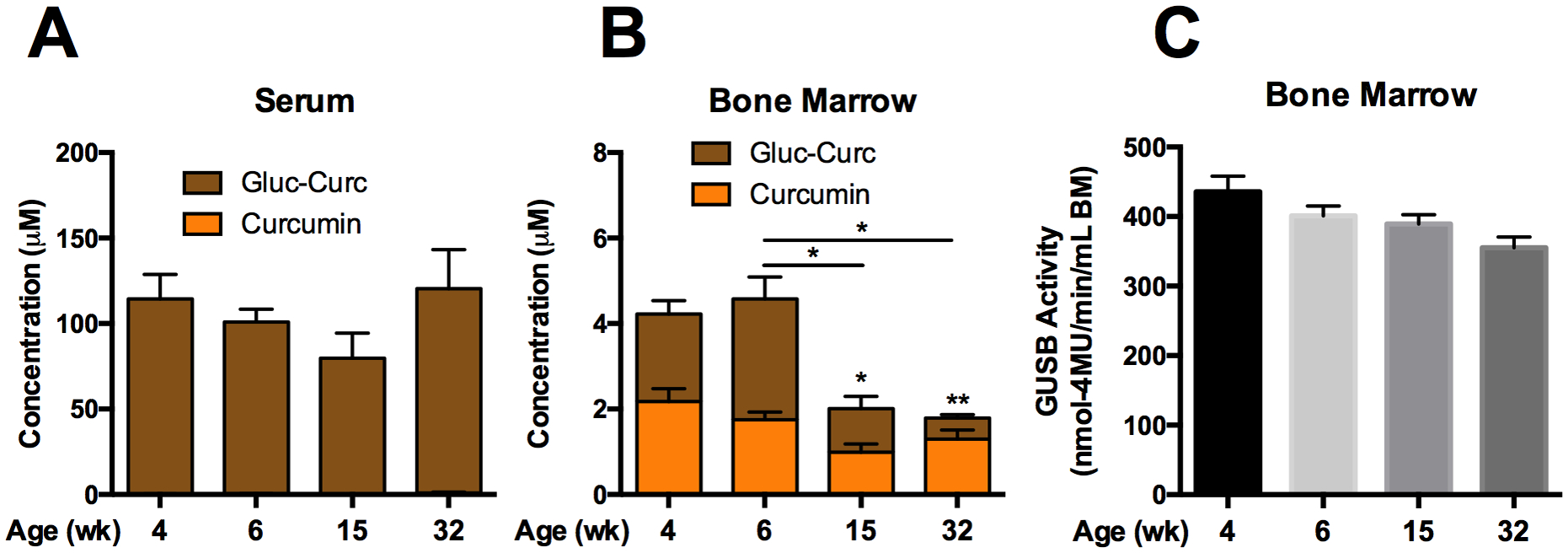

Effects of sexual and skeletal development on curcumin metabolism in bone

In sexually and skeletally immature (4 or 6-week) vs. mature (15 or 32-week) female mice treated orally with curcumin[48], circulating metabolites were again primarily the glucuronide, not the aglycone, with serum concentrations that did not differ across developmental stages (Fig. 2A). In bone, total curcumin metabolite concentrations were significantly higher in immature (vs mature) mice (Fig. 2B). Aglycone curcumin concentrations, while statistically unchanged, also trended higher in immature mice, such that >40% of curcumin-glucuronide distributing to bone following ingestion was deconjugated throughout development. Consistent with this similar, high deconjugation capacity, bone GUSB activity, while trending downwards slightly with age, did not vary significantly during sexual and skeletal development, from 4 to 32 weeks of age (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Effect of age on curcumin metabolism and GUSB activity in mouse bone marrow.

Curcumin metabolites in A) serum and B) bone marrow of female C57BL/6J mice, 30 minutes following oral gavage with 500 mg/kg curcumin (n=4–16/group). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, total curcumin (curcumin + curcumin-glucuronide) vs 4wk or as specified. GUSB enzyme activity in C) female (n=4–16/group) C57BL/6J mice.

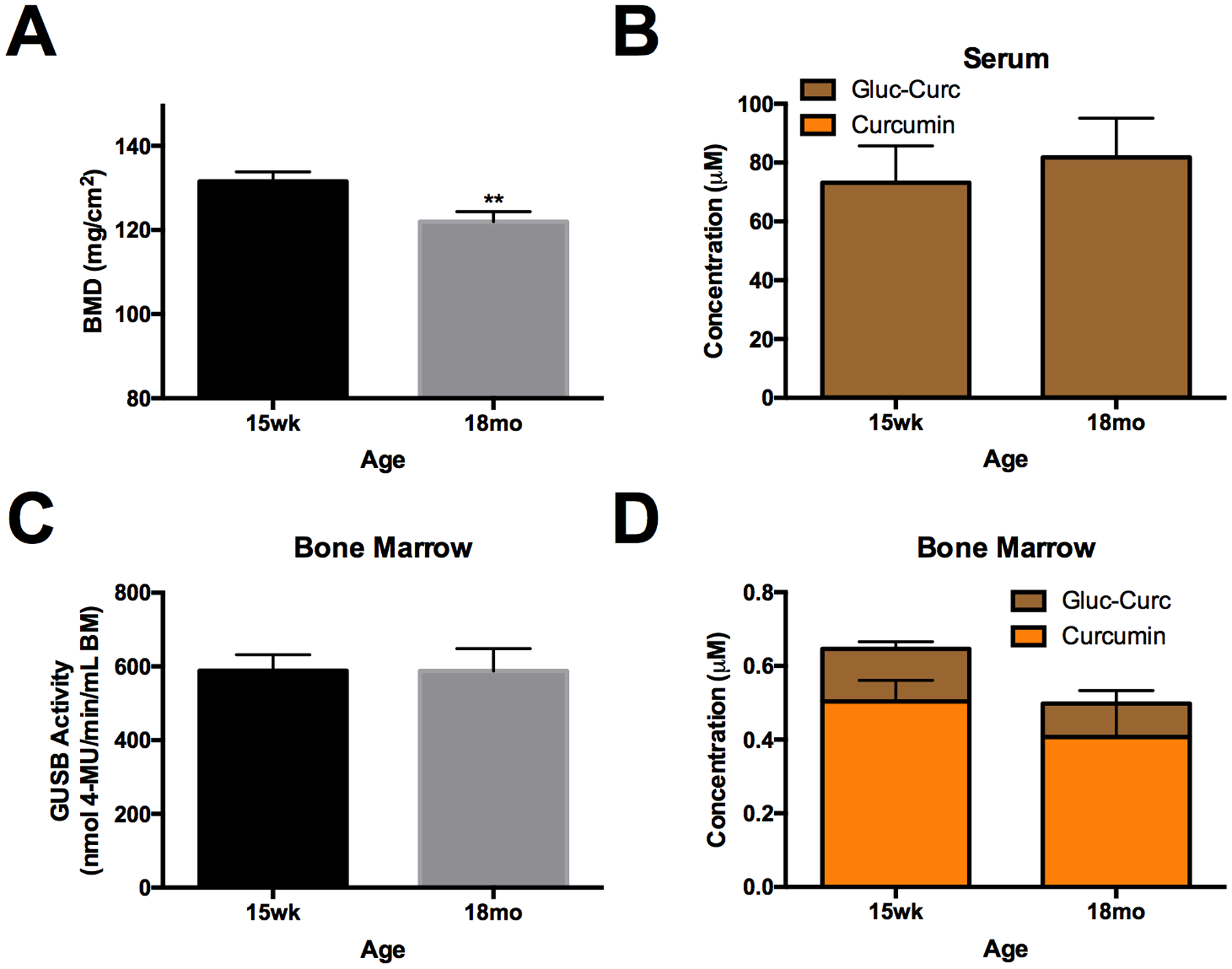

Effect of aging on curcumin metabolism in bone

As anticipated,[49] 18-month-old male mice exhibited age-related bone loss relative to skeletally mature (15-week-old) male mice (Fig. 3A). However, serum metabolites following oral curcumin ingestion, which again were primarily glucuronides, were not altered in aged mice (Fig. 3B), nor was bone GUSB activity (Fig.3C). Total bone metabolites levels, while trending slightly lower in aged mice, were also statistically unchanged, and aglycone curcumin levels remained high, such that >77.9% of curcumin metabolites distributing to bone were deconjugated (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Effect of age-related bone loss on GUSB activity and curcumin metabolism in bone.

A) Bone mineral density (BMD) in the distal (25%) femur of aged 18mo (vs 15 wk) male C57BL/6 mice (n=10–11/group). Curcumin metabolites in B) serum and D) bone marrow of 15wk vs 18mo male C57BL/6J mice (n=5/group), 30 minutes following oral gavage with 500 mg/kg curcumin. C) GUSB enzyme activity in aged 18mo (vs 15 wk) male C57BL/6 mice (n=10–11/group). No significant differences between 18 mo vs 15 wk except ** p < 0.01, as indicated.

Effect of ovariectomy on curcumin metabolism in bone

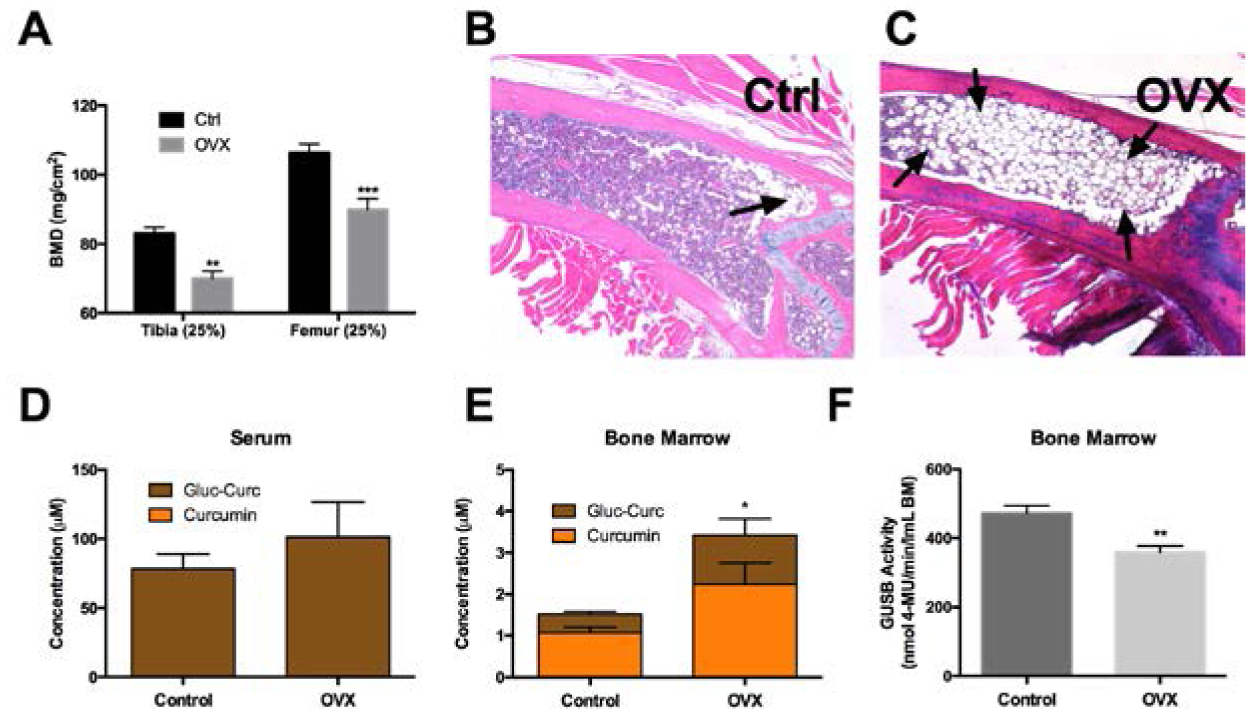

As anticipated [50], BMD in trabeculae-enriched regions of OVX mice decreased (Fig. 4A) and bone marrow adiposity increased (Fig. 4B,C), compared to age-matched controls. Serum curcumin metabolites levels following oral treatment, while trending higher in OVX mice, were statistically unchanged as compared to age-matched controls (Fig. 4D). In bone, total curcumin metabolite levels were significantly higher (2.3-fold, p< 0.05) in OVX mice (Fig. 4E). Aglycone curcumin levels, while statistically unchanged, also tended to be higher in OVX mice. GUSB activity in bone was decreased (−24.2%, p < 0.01) in OVX mice (Fig. 4F), while still remaining sufficient to deconjugate the majority of curcumin-glucuronide distributing to OVX bone (Fig. 4E), findings that were also confirmed in a separate experiment (data not shown).

Figure 4. The effect of ovariectomy on bone marrow GUSB activity and curcumin metabolism.

A) Bone mineral density (BMD) of the proximal tibia and distal femur 8 weeks post-OVX vs age-matched (32 week) female C57BL/6J controls (n=5/group). ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs ctrl. B) H&E of distal femur in control vs C) OVX, demonstrating increased adiposity in OVX (arrow). Curcumin metabolites in D) serum or E) marrow of control or OVX mice 30 min following oral gavage with 500 mg/kg curcumin (n=5/group). * p < 0.05 for total curcumin (curcumin + curcumin-glucuronide). F) GUSB enzyme activity in bone marrow of control or OVX mice (n=4/group). ** p < 0.01.

Effect of focal osteolysis and bone metastatic tumors on curcumin metabolism in bone

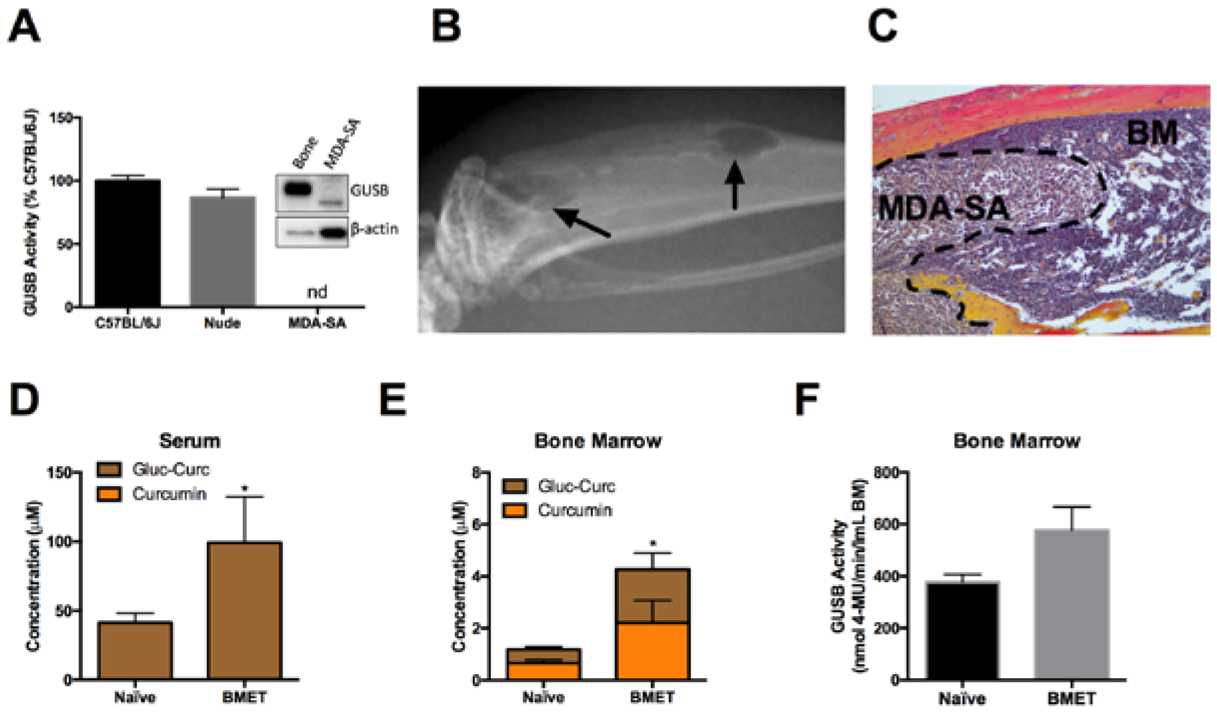

As anticipated[15], inoculation of athymic 4-week-old female mice (n=5), which have the same baseline GUSB activity as age- and sex-matched wild type mice (Fig 5A), with GUSB-negative human MDA-SA cells (Fig. 5A) resulted in the formation of hind limb osteolytic BMET occupying 10 ± 6% of total hind limb radiographic area (Fig. 5B,C). Interestingly, in BMET-bearing mice dosed orally with curcumin, serum curcumin metabolite concentration (primarily curcumin-glucuronide) was markedly higher (>2-fold) than in control mice (Fig. 5D). Similarly, in bone, total curcumin metabolites were 3.6-fold higher and aglycone curcumin concentrations also trended higher in mice with BMETs as compared to controls (Fig. 5E). Consistent with this sustained capacity of tumor-bearing mice to deconjugate the majority of curcumin-glucuronide present in bone, GUSB activity in bone marrow was preserved in tumor bearing marrow, and indeed tended to be higher than control mice (Fig. 5F), although the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 5. Effect of MDA-SA bone metastases on curcumin metabolism and GUSB activity in circulation and bone.

A) GUSB activity or protein expression (inset) in bone marrow from C57BL/6J vs athymic nude mice and in human MDA-SA breast cancer cells, normalized to protein (n=3/group). Note: Equal protein loading was confirmed for western (see methods) since actin content differed by cell type. B) Radiographic (black arrow) and C) histologic images of MDA-SA bone metastasis in the tibia of a female athymic nude mouse. Curcumin metabolites in D) serum and E) bone marrow of nude mice without (naïve) or with (BMET) MDA-SA tumors, 30 minutes following oral gavage with 500 mg/kg curcumin (n=4/group). * p < 0.05 for total curcumin (curcumin + curcumin-glucuronide). F) GUSB enzyme activity in bone marrow of naïve or BMET nude mice (n=5/group).

Regional differences in curcumin metabolism within bone

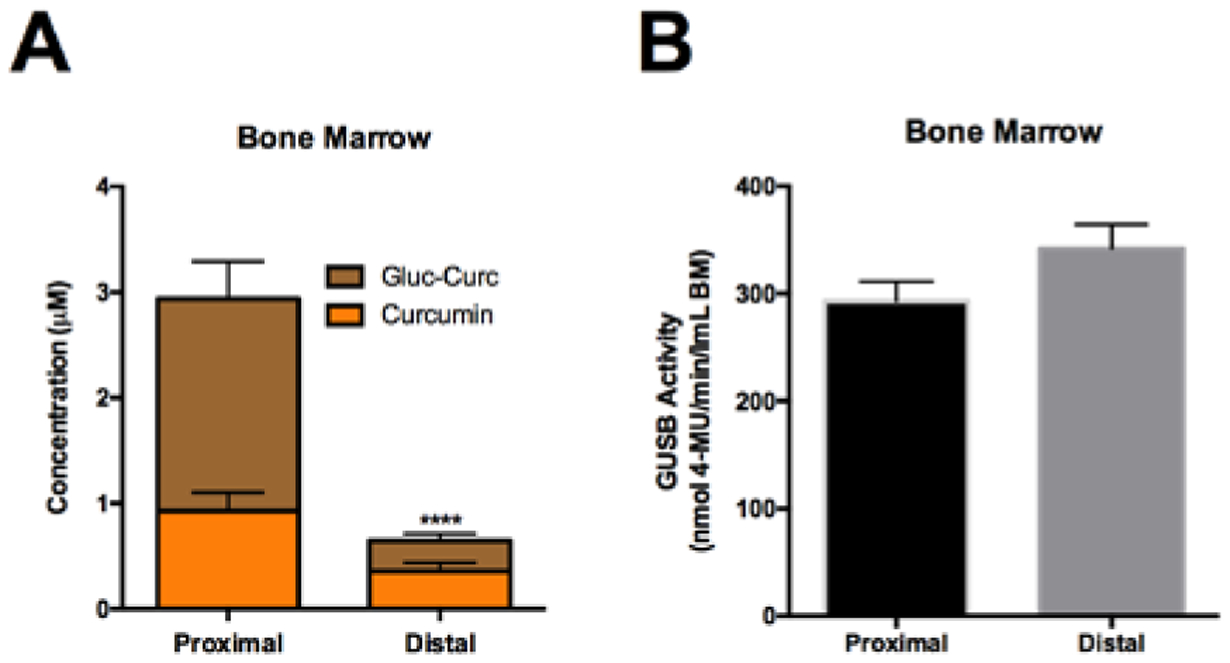

Total curcumin metabolite levels were 4.6-fold higher in trabeculae-enriched regions of bone (Fig. 6A, proximal tibia), which are sites of bone loss in aging (Figs. 3A), OVX (Fig. 4A), and BMET (Fig. 5B), as compared to cortical-enriched bone (Fig. 6A, distal tibia) following oral curcumin treatment . Aglycone curcumin levels, while trending slightly higher in the proximal tibiae (Fig. 6A), did not increase proportionally in OVX (vs. control) mice (44.7% ± 2.7% vs. 24.8% ± 5.6, respectively), representing a significantly lower percent of the total substrate in this compartment (p < 0.001). GUSB activity, normalized to bone marrow volume, was the same in both compartments (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Differences in curcumin metabolism and GUSB activity in proximal vs distal tibia.

Bone marrow was harvested from the tibia of female, 4wk C57BL/6J mice and partitioned into the proximal 25% or distal 75%. A) Curcumin metabolites in proximal vs distal bone marrow, 30 minutes following oral gavage with 500 mg/kg curcumin (n=4/group). **** p < 0.0001 for total curcumin (curcumin + curcumin-glucuronide). B) Quantitation of GUSB activity between proximal and distal tibia (n=4–5/group).

Effect of chronic curcumin dosing on curcumin metabolism

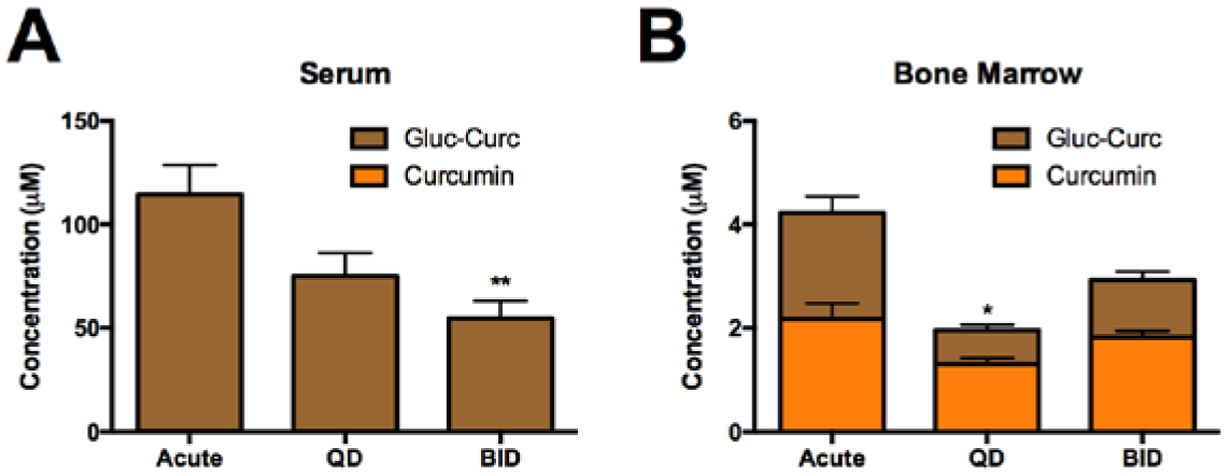

Following a single oral curcumin dose (500 mg/kg), glucuronidated curcumin levels peaked at 30 minutes in serum and bone, with a half-life of 7.3 hours (h) in bone, which exceeded serum (4.4h) (Supplemental Fig. 1). When curcumin (500 mg/kg [HED = 2.5 g]) was dosed chronically either once (QD) or twice (BID) daily, as recommended by turmeric dietary supplement manufacturers[13], serum metabolites concentrations tended to be lower than those achieved with a single acute dose, reaching statistical significance with BID dosing. Total curcumin metabolites levels in bone also tended to be lower with chronic dosing; however, bone aglycone curcumin levels were maintained (Fig. 7B), with bone concentrations within the range required for curcumin inhibition of bone-resorbing osteoclast formation (Fig. 8A).

Figure 7. Metabolism of curcumin in serum and bone marrow following chronic curcumin dosing.

Curcumin metabolites were assayed 30 minutes after final dose in A) serum and B) bone marrow of 4-week (acute or QD dosing) or 6-week (BID dosing) female C57BL/6J following chronic or acute curcumin (500 mg/kg) dosing (n=4/group). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs acute for total curcumin.

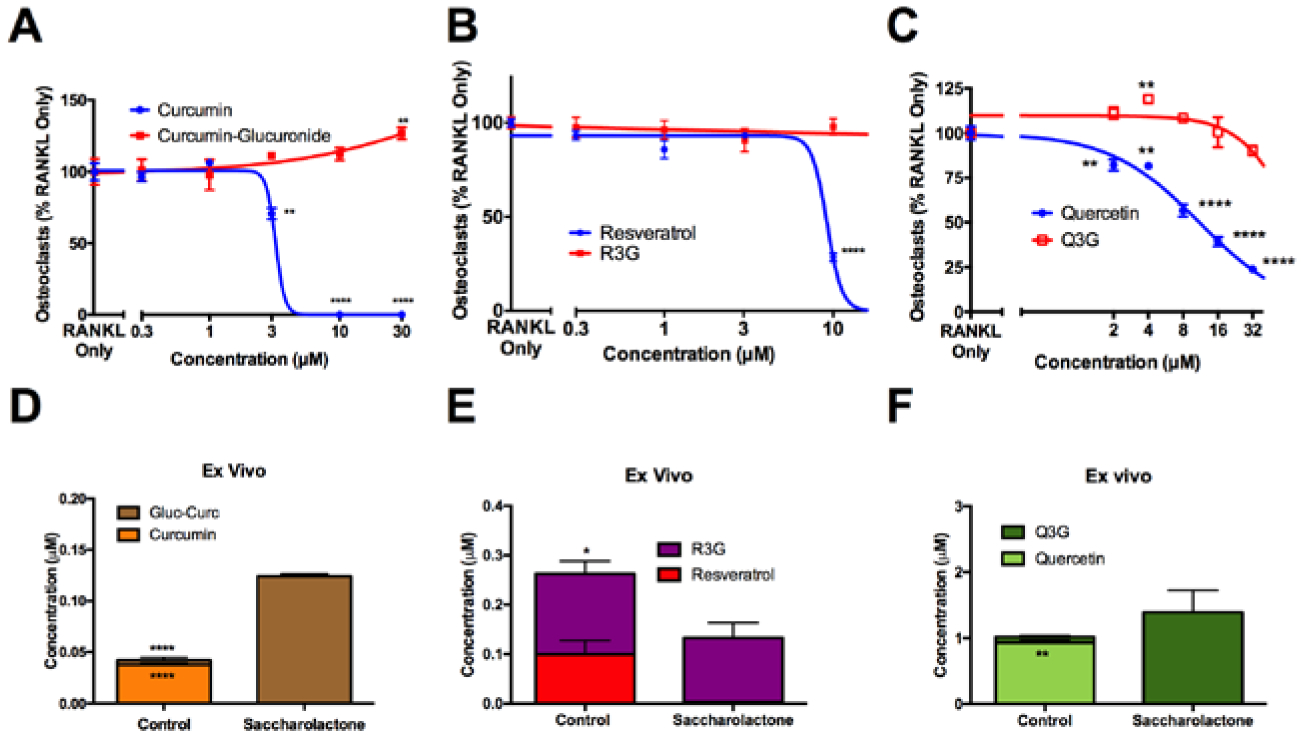

Figure 8. Deconjugation of other bone-protective dietary polyphenols by bone marrow β-glucuronidase.

Bioactivity of aglycone vs glucuronidated polyphenols in blocking RANKL-stimulated osteoclast formation for A) curcumin vs curcumin-glucuronide, B) resveratrol vs resveratrol-3-glucuronide (R3G), or C) quercetin vs quercetin-3- (Q3G). ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001. D) Curcumin-glucuronide (0.5 μM), E) R3G (0.5 μM), or F) Q3G (3 μM) were incubated ex vivo with bone marrow from 4-week-old female C57BL/6J mice in sodium acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 5) for 2 hours at 4°C with or without saccharolactone (10 mM) (n=3–5/group). * p< 0.05, **** p < 0.0001. Aglycone and glucuronides of curcumin, resveratrol, and quercetin were assayed in cell-free supernatant by LC/MS.

Bone specific GUSB-mediated metabolism and bioactivity of glucuronides of bone protective dietary polyphenols

Aglycone forms of curcumin, resveratrol and quercetin each inhibited RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis in a concentration-dependent fashion (IC50 of 3, 9 and 11 μM, respectively), while their glucuronides were without effect (Fig. 8A–C). Curcumin-glucuronide, resveratrol-3-glucuronide (R3G), and quercetin-glucuronide were each deconjugated in a β-glucuronidase-dependent (i.e., saccharolactone-inhibitable) manner during ex vivo incubation with bone marrow (Fig. 8D–F), demonstrating a similar capacity of bone to form bioactive, osteoclast-inhibiting aglycones that was not compound-specific. Of note, the lower concentrations of R3G remaining when GUSB deconjugation was inhibited were suggestive of possible alternative metabolic pathways; however there was no evidence of other resveratrol metabolites commonly detected in vivo being formed (i.e., resveratrol-4-glucuronide, resveratrol-disulfate, resveratrol-monosulfate, or mixed resveratrol-glucuronide-sulfate conjugates; data not shown)[42,43].

DISCUSSION

In mice, as in humans, orally ingested curcumin is rapidly glucuronidated to form curcumin glucuronide, a major circulating metabolite, while serum levels of aglycone curcumin, the bioactive moiety in bone, are exceeding low. However, bone is notable for its extremely high GUSB content relative to other organs[21]. In prior studies, sufficient GUSB enzyme was present in bones of mice with a normal GUS gene haplotype (C57BL/6) to deconjugate the majority of curcumin-glucuronide substrate distributing to this site following oral curcumin ingestion. The GUSB dependence of bone-specific deconjugation and pharmacokinetic effects of GUSB deficiencies in excess of 75% on curcumin-glucuronide metabolism were documented in C57BL/6 mice with a loss of function GUS gene mutation and C3H/HeJ mice with a low-GUS haplotype[21]. These findings raised the question of whether endogenous modulation of GUSB activity within bone and/or tissue distribution of the glucuronide could be altered in disease settings where the aglycone is needed for bone protection, as may occur, for example, in age- or menopause-related bone loss where sex hormones capable of inducing GUSB expression are deficient. While dietary supplements cannot be marketed for disease treatment, the current widespread use of curcumin-containing dietary supplements to treat musculoskeletal disorders makes this a clinically relevant question.

While pharmacologic or replacement doses of estrogen or testosterone have previously been documented to alter GUSB activity in certain organs[24,28], in the studies reported here, GUSB activity in bone was constant across sexual and skeletal development and did not differ between male and female mice. Circulating glucuronidated curcumin levels were also constant during development following oral ingestion of curcumin. However, bone substrate content was >2-fold higher in skeletally-immature, growing mice, possibly attributable to increased blood flow associated with this high turnover state and/or bone milieu changes associated with high turnover itself[51,52]. Similarly, 2.3- to 3.6-fold higher glucuronide substrate content in bone was also documented in OVX and BMET-bearing mice (vs age matched controls), two additional conditions where bone turnover is markedly enhanced, with variable effects reported on net changes in blood flow [51,53,54]. In BMET-bearing mice, elevated serum levels of curcumin glucuronide, which were otherwise unchanged in mice across development or disease states, may have also contributed to higher glucuronide substrate content in bone. In high-turnover bone microenvironments where glucuronidated substrate concentrations were increased in bone (immature, OVX, BMET), aglycone curcumin content tended to increase proportionally, suggesting that sufficient GUSB was present in bone to convert the majority of inactive curcumin glucuronide to the active aglycone following ingestion of a clinically relevant curcumin dose (5g, HED)[13,55].

Bone GUSB activity was significantly altered only in OVX female mice, where GUSB activity was decreased by 24% as compared to naïve age-matched controls. The magnitude of this loss is much less than the >75% reductions in GUSB activity that resulted in significant decreases in the capacity of bone to deconjugate curcumin glucuronide in mice with genetic GUSB defects[21]. Because the amount of aglycone curcumin product formed (absolute or percent of total metabolites) was not significantly altered in OVX mice, this suggests that sufficient GUSB was still present to deconjugate the majority of substrate delivered to OVX bone following curcumin ingestion. The pharmacologic impact of GUSB reduction between 25–75% are therefore unknown, but of possible relevance given the range of GUSB expression in human populations [56,57]. Because GUSB levels were unchanged in aged bone and only reduced in OVX mice, increases in bone adiposity, which are similar in magnitude in both states in C57BL/6 mice (and in humans) and could theoretically alter GUSB levels via associated changes in hematopoietic marrow cell populations, are not likely to be driving low GUSB activity levels in OVX mice[8,23,29–31]. Instead, because organ-specific decreases in GUSB have previously been reported in OVX mice uteri, a classic estrogen-responsive tissue (but not liver or kidney)[25,26], bone may be one additional tissue where estrogen deficiency can lead to reductions in GUSB, an enzyme that is also estrogen-responsive in humans[22,27,56]. Interestingly, in mice with GUSB-negative BMET lesions, bone GUSB activity trended higher (and bone glucuronide substrate levels were increased), suggesting the possibility that tumoral factors promote local aglycone bioavailability , consistent with curcumin’s in vivo protective effect in this breast cancer BMET model[15].

Of possible clinical relevance, glucuronidated curcumin substrate levels within bone were markedly (5-fold) higher in trabeculae-enriched regions that are an important site of menopausal, age-related and BMET-driven osteolysis, as compared to cortical bone-enriched regions in curcumin-treated mice, a finding possibly attributable to increased blood flow in these metabolically active sites[58,59]. Notably, while aglycone curcumin concentrations also tended to be higher in trabecular regions, the aglycone did not increase proportionally, suggesting the possibility that GUSB enzyme activity could have been saturated in this zone of high substrate concentration.

Also of clinical importance, the capacity of bone to deconjugate curcumin glucuronide was not reduced in response to chronic curcumin administration at dosing intervals recommended by turmeric dietary supplement manufacturers[13]. Substrate levels in bone following twice daily ingestion of curcumin at 12 hour intervals were higher as compared with once daily dosing, as would be expected given the 7.3-hour half-life of curcumin glucuronide in bone, which, interestingly exceeds that of curcumin glucuronide in the circulation. The IC50 for curcumin inhibition of osteoclast formation was the same order of magnitude as average metabolite concentrations in bone over 24 h following oral curcumin ingestion. When combined with evidence of markedly higher metabolite levels within periarticular, trabeculae-enriched areas most affected by common resorptive bone disorders., these findings suggest that sufficient bioactive curcumin may be present in bone to support anti-osteoclastic activity.

Glucuronides are usually the most abundant circulating metabolite of ingested dietary polyphenols, many of which have reported bone protective effects[33,34]. Thus, it is notable that the glucuronides of three such bone protective polyphenols, curcumin, quercetin and resveratrol, all required deconjugation for anti-osteoclastogenic activity, a key mediator of bone loss in all resorptive bone diseases. Moreover, all three were recognized as GUSB substrates and deconjugated by bone in a GUSB-dependent fashion.

In toto, the findings reported here suggest that in vivo bone protective effects of curcumin and other dietary polyphenols with prolonged bioavailability due to circulating glucuronidated metabolites may require GUSB-mediated deconjugation within bone to form the bioactive aglycone. Glucuronidated substrate availability in bone may be higher in states of high bone turnover (e.g., developing skeleton, OVX, bone metastases) and result in proportional increases in aglycone formation, which in curcumin-treated mice led to aglycone levels on the order of those required for inhibition of osteoclast differentiation. The change in bone GUSB activity that uniquely accompanied estrogen-deficiency-related bone loss (−24%) was insufficient to alter aglycone formation in mice with a normal GUSB haplotype, where bone GUSB enzyme activity remained sufficient to deconjugate the majority of glucuronide substrate and only seemed to approach saturation in regions of extremely high substrate concentrations. Given the wide range of GUSB expression in human populations[56,57], however, it remains possible that bone protective effects of curcumin and other bone protective polyphenols requiring the aglycone for bioactivity may be compromised in individuals with GUSB-low phenotypes, particularly in settings where GUSB expression may be further reduced, such as menopause or other estrogen deficiency states, a postulate that requires further testing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) and the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01CA174926 and R34 AT007837 to J.L.F., R01AT006896 to C.S., and F31AT009938 to A.K.); the United States Department of Agriculture (2014-38420-21799 National Needs Fellowship to A.K.) ; and the American Heart Association (16POST27250138 postdoctoral fellowship to P.B.L.). Mass spectrometric analyses were performed in part through Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Digestive Disease Research Center supported by NIH grant P30DK058404 Core Scholarship. Pharmacokinetic analyses were performed in part through the University of Arizona Cancer Center’s Analytical Chemistry Shared Resource supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA023074.

REFERENCES

- [1].Drake MT, Clarke BL, Lewiecki EM, Clin. Ther 2015, 37, 1837–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wada T, Nakashima T, Hiroshi N, Penninger JM, Trends Mol. Med 2006, 12, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kim WK, Ke K, Sul OJ, Kim HJ, Kim SH, Lee MH, Kim HJ, Kim SY, Chung HT, Choi HS, J. Cell. Biochem 2011, 112, 3159–3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Funk JL, Frye JB, Oyarzo JN, Kuscuoglu N, Wilson J, McCaffrey G, Stafford G, Chen G, Lantz RC, Jolad SD, Sólyom AM, Kiela PR, Timmermann BN, Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 3452–3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mohamad N, Soelaiman I-N, Chin K-Y, Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1317–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cauley JA, Steroids 2015, 99, 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Farr JN, Khosla S, Bone 2019, 121, 121–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Justesen J, Stenderup K, Ebbesen E, Mosekilde L, Steiniche T, Kassem M, Biogenerentology 2001, 2, 165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Clarke TC, Black L, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL, Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches among Adults in the United States: New Data, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [10].Smith T, Gillespie M, Eckl V, Knepper J, Reynolds CM, HerbalGram 2019, 123, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Groff R, Strom M, Hopkins L, Feng L, Hopkins A, Funk J, FASEB J. 2017, 31, Supplement lb396. [Google Scholar]

- [12].DeSalvo JC, Skiba MB, Howe CL, Haiber KE, Funk JL, Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2019, 71, 0–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Skiba MB, Luis PB, Alfafara C, Billheimer D, Schneider C, Funk JL, Mol. Nutr. Food Res 2018, 62, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wright LE, Frye JB, Timmermann BN, Funk JL, Agric J. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 9498–9504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wright LE, Frye JB, Lukefahr AL, Timmermann BN, Mohammad KS, Guise TA, Funk JL, J. Nat. Prod 2013, 76, 316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Frye J, Timmerman B, Funk J, BMC Complement. Altern. Med 2012, 12, P55. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kunihiro AG, Brickey JA, Frye JB, Luis PB, Schneider C, Funk JL, J. Nutr. Biochem 2019, 63, 150–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Khanizadeh F, Rahmani A, Asadollahi K, Ahmadi MRH, Arch. Endocrinol. Metab 2018, 62, 438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yousefzadeh MJ, Zhu Y, McGowan SJ, Angelini L, Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H, Xu M, Ling YY, Melos KI, Pirtskhalava T, Inman CL, McGuckian C, Wade EA, Kato JI, Grassi D, Wentworth M, Burd CE, Arriaga EA, Ladiges WL, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nelson KM, Dahlin JL, Bisson J, Graham J, Pauli GF, Walters MA, J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 1620–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kunihiro AG, Luis PB, Brickey JA, Frye JB, Chow HHS, Schneider C, Funk JL, J. Nat. Prod 2019, 82, 500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cohen SL, Huseby RA, Cancer Res. 1951, 11, 52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Elbaz A, Rivas D, Duque G, Biogenerentology 2009, 10, 747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fishman WH, Fishman LW, J. Biol. Chem 1944, 152, 487–8. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fishman WH, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1951, 54, 548–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fishman WH, Farmelant MH, Endocrinology 1953, 52, 536–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Contractor S, Shane B, Biochem. J 1972, 128, 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lund SD, Gallagher PM, Wang B, Porter SC, Ganschow RE, Mol. Cell. Biol 1991, 11, 5426–5434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Scheller EL, Cawthorn WP, Burr AA, Horowitz MC, MacDougald OA, Trends Endocrinol. Metab 2016, 27, 392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Scheller EL, Khoury B, Moller KL, Wee NKY, Khandaker S, Kozloff KM, Abrishami SH, Zamarron BF, Singer K, Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2016, 7, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pagnotti GM, Styner M, Uzer G, Patel VS, Wright LE, Ness KK, Guise TA, Rubin J, Rubin CT, Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 2019, 15, 339–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pfister K, Paigen K, Watson G, Chapman V, Biochem. Genet 1982, 20, 519–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rothwell JA, Urpi-Sarda M, Boto-Ordoñez M, Llorach R, Farran-Codina A, Barupal DK, Neveu V, Manach C, Andres-Lacueva C, Scalbert A, Mol. Nutr. Food Res 2016, 60, 203–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].D’Archivio M, Filesi C, Varì R, Scazzocchio B, Masella R, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2010, 11, 1321–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Woo J, Nakagawa H, Notoya M, Yonezawa T, Udagawa N, Lee I, Ohnishi M, Hagiwara H, Nagai K, Biol. Pharm. Bull 2004, 27, 504–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tsuji M, Yamamoto H, Sato T, Mizuha Y, Kawai Y, Taketani Y, Kato S, Terao J, Inakuma T, Takeda E, Bone Miner J. Metab. 2009, 27, 673–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yeh SL, Lin YC, Lin YL, Li CC, Chuang CH, Eur. J. Nutr 2016, 55, 413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Day AJ, Mellon F, Barron D, Sarrazin G, Morgan MRA, Williamson G, Free Radic. Res 2001, 35, 941–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].He X, Andersson G, Lindgren U, Li Y, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2010, 401, 356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ornstrup MJ, Harsløf T, Kjær TN, Langdahl BL, Pedersen SB, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 2014, 99, 4720–4729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhao H, Li X, Li N, Liu T, Liu J, Li Z, Xiao H, Li J, Br. J. Nutr 2014, 111, 836–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chow H-HS, Garland LL, Hsu CH, Vining DR, Chew WM, Miller JA, Perloff M, Crowell JA, Alberts DS, Cancer Prev. Res 2010, 3, 1168–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chow H-HS, Garland LL, Heckman-Stoddard BM, Hsu CH, Butler VD, Cordova CA, Chew WM, Cornelison TL, J. Transl. Med 2014, 12, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nair AB, Jacob S, J. Basic Clin. Pharm 2016, 7, 27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Boocock DJ, Faust GES, Patel KR, Schinas AM, Brown VA, Ducharme MP, Booth TD, Crowell JA, Perloff M, Gescher AJ, Steward WP, Brenner DE, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 2007, 16, 1246–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wang LX, Heredia A, Song H, Zhang Z, Yu B, Davis C, Redfield R, J. Pharm. Sci 2004, 93, 2448–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Andres S, Pevny S, Ziegenhagen R, Bakhiya N, Schäfer B, Hirsch-Ernst KI, Lampen A, Mol. Nutr. Food Res 2018, 62, DOI 10.1002/mnfr.201700447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Glatt V, Canalis E, Stadmeyer L, Bouxsein ML, J. Bone Miner. Res 2007, 22, 1197–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Farr JN, Xu M, Weivoda MM, Monroe DG, Fraser DG, Onken JL, Negley BA, Sfeir JG, Ogrodnik MB, Hachfeld CM, LeBrasseur NK, Drake MT, Pignolo RJ, Pirtskhalava T, Tchkonia T, Oursler MJ, Kirkland JL, Khosla S, Nat. Med 2017, 23, 1072–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wright LE, Christian PJ, Rivera Z, Van Alstine WG, Funk JL, Bouxsein ML, Hoyer PB, J. Bone Miner. Res 2008, 23, 1296–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Marenzana M, Arnett TR, Bone Res. 2013, 1, 203–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cheng JN, Frye JB, Whitman SA, Funk JL, Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2019, ePub, DOI 10.1007/s10585-019-10012-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Egrise D, Martin D, Neve P, Vienna A, Verhas M, Schoutens A, Calcif. Tissue Int 1992, 50, 336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Raymaekers K, Stegen S, van Gastel N, Carmeliet G, Bonekey Rep. 2015, 4, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Cheng A-L, Hsu C-H, Lin J-K, Hsu M-M, Ho Y-F, Shen T-S, Ko J-Y, Lin J-T, Lin B-R, Wu M-S, Yu H-S, Jee S-H, Chen G-S, Chen T-M, Chen C-A, Lai M-K, Pu Y-S, Pan M-H, Wang Y-J, Tsai C-C, Hsieh C-Y, Anticancer Res. 2001, 21, 2895–2900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lombardo A, Bairati C, Goi G, Roggi C, Maccarini L, Bollini D, Burlina A, Clin. Chim. Acta 1996, 247, 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gratz M, Kunert-Keil C, John U, Cascorbi I, Kroemer HK, Pharmacogenet. Genomics 2005, 15, 875–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sivaraj KK, Adams RH, Dev. 2016, 143, 2706–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Anetzberger H, Thein E, Becker M, Zwissler B, Messmer K, Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 2004, 424, 253–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.