Abstract

Objective. To identify and build consensus on priority leadership and professionalism attributes for pharmacy student development among faculty, preceptors, and students.

Methods. One hundred individuals (27 faculty members, 30 preceptors, 43 students) were invited to participate in a three-round, modified Delphi. Published literature on leadership and professionalism informed the initial attribute list. In the first round, participants reviewed and provided feedback on this list. In the second round, participants prioritized attributes as highly important, important, or less important for pharmacy student development. Leadership and professionalism attributes that achieved an overall consensus (a priori set to ≥80.0%) of being highly important or important for pharmacy student development were retained. In the third round, participants rank ordered priorities for leadership and professionalism attributes.

Results. Fifteen leadership and 20 professionalism attributes were included in round one while 21 leadership and 21 professionalism attributes were included in round two. Eleven leadership and 13 professionalism attributes advanced to round three. Consensus was reached on the top four leadership attributes (adaptability, collaboration, communication, integrity) and five professionalism attributes (accountability, communication, honor and integrity, respect for others, trust). Differences were observed for certain attributes between faculty members, preceptors, and/or students.

Conclusion. The modified Delphi technique effectively identified and prioritized leadership and professionalism attributes for pharmacy student development. This process facilitated consensus building and identified gaps among stakeholders (ie, faculty, preceptors, students). Identified gaps may represent varying priorities among stakeholders and/or different opportunities for emphasis and development across classroom, experiential, and/or cocurricular settings.

Keywords: leadership, professionalism, Delphi methodology

INTRODUCTION

Today’s health care environments are increasingly dynamic and require pharmacy professionals to engage in a variety of roles and responsibilities that span the boundaries of traditional practice.1,2 Pharmacists must strive to meet the needs of patients, while also balancing the demands of a rapidly changing health care delivery system.3 The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) 2008-2009 Argus Commission examined issues related to building a sustainable system of leadership development for pharmacy.4 Specifically, their proposed policy statement, “Curricular modifications should occur such that competencies for leading change in pharmacy and health care are developed in all student pharmacists, using a consistent thread of didactic, experiential and cocurricular learning opportunities,” clearly identifies a need for emphasizing leadership development in all aspects of pharmacy education.4,5

Building upon this statement and recognizing the importance of developing future leaders and professionals, Standard 4 of the 2016 Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Standards (Standards 2016) requires programs to develop leadership and professionalism within their graduates.6 Preparing pharmacy students to be effective leaders and professionals is imperative as pharmacists continue to face an ever-transforming health care delivery system.7

While Standards 2016 describes the leadership educational outcome as “the graduate is able to demonstrate responsibility for creating and achieving shared goals, regardless of position,”6 literature suggests that how leadership is defined, conceptualized, and assessed varies within pharmacy education.8 Previous efforts have aimed to advance the understanding of leadership in pharmacy and reach consensus using Delphi methodology.9-11 The Delphi is a research methodology involving a structured process for developing and measuring consensus on complex topics with limited or conflicting evidence using a panel of experts.12 Specific to student leadership development, Traynor and colleagues used a 26-member Delphi panel that included leadership instructors across pharmacy education.9,10 The purpose of their study was to identify guiding principles for student leadership development in the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum. While 12 guiding principles were identified,9,10 one limitation to this approach was that Delphi participation was limited to pharmacy faculty members involved in teaching leadership, thus only representing one component (ie, didactic) of the pharmacy student learning environment.

In addition to leadership, Standards 2016 describes the professionalism educational outcome as “The graduate is able to exhibit behaviors and values that are consistent with the trust given to the profession by patients, other health care providers, and society.”6 Similar to leadership, how professionalism is defined may vary across pharmacy education as one consistent framework has not been identified and endorsed.13-15 Further, the American Pharmacists Association Academy of Student Pharmacists and the AACP Council of Deans Taskforce on Professionalism have outlined recommendations for developing professionalism in graduates, highlighting the importance of building faculty consensus and involving preceptors in defining professional educational outcomes.13

Also new within Standards 2016 was the inclusion of a cocurriculum requirement.6 While cocurricular activities, such as service learning, student organizations, and community outreach, are not new to pharmacy programs,16-20 the requirement to document student involvement in these activities and demonstrate how these experiences assist students in developing competency in the affective domains (eg, leadership, professionalism) was a new expectation. Notably, planning of cocurricular activities is often student-driven with oversight support provided by faculty members.16-20

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Eshelman School of Pharmacy, leadership and professionalism have been taught and evaluated throughout didactic courses, experiential education, and the co-curriculum. However, how faculty members, preceptors, and others defined leadership and professionalism were not consistently aligned, leading to varied instruction and assessment of student competency. Thus, an opportunity was identified to standardize the teaching and assessment of these important topics and key stakeholders were sought to engage in this process. The purpose of this study was to identify and build consensus on priority leadership and professionalism attributes for pharmacy student development among expert faculty members, preceptors, and students.

METHODS

In January 2019, a sample of 100 individuals (27 faculty members, 30 preceptors, and 43 students) involved in the PharmD curriculum at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy were invited to participate in a three-round modified Delphi. The Delphi process is research methodology that involves a panel of experts who review and reach consensus on data through iterative feedback to measure agreement.21-24 For this study, invited participants represented key constituencies the research team recognized as experts engaged in the didactic, experiential, or cocurricular aspects of the student learning experience. Participants included faculty members who were teaching leadership and professional development courses within the PharmD curriculum; preceptors who were working in diverse experiential settings throughout the region; and students who were serving in pharmacy student government, class leadership, and/or student organization leadership roles within the cocurriculum and thus charged with representing the student body. These stakeholder groups were intentionally selected as they represented three distinct settings where students develop as leaders and professionals: didactic coursework (faculty members), experiential education (preceptors), and the cocurriculum (students). Attrition was managed by making participation in subsequent Delphi rounds contingent on involvement in the previous round. This study was submitted to the UNC Institutional Review Board and exempted from review.

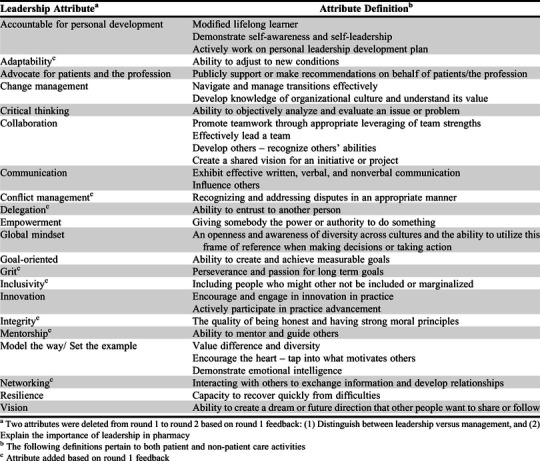

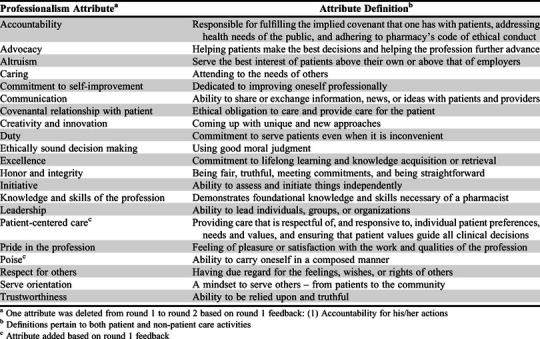

In the first round, participants were given the opportunity to review an emailed list of 15 leadership (Table 1) and 20 professionalism (Table 2) attributes, provide feedback, and add additional attributes important for pharmacy student leadership and professional development. The original list of attributes was informed from published literature outlining important pharmacy leadership9,10,25 and professionalism13-15,26 characteristics. All feedback was reviewed independently, and themes were discussed as a group by the research team for additions and modifications to the attribute lists.

Table 1.

Leadership Attributes and Definitions Used in the Modified Delphi

Table 2.

Professionalism Attributes and Definitions Used in the Modified Delphi

Twenty-one leadership (Table 1) and 21 professionalism (Table 2) attributes were included in the second round. Each attribute was defined using relevant literature. The definitions were included in the survey instrument, which was administered through Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com, Provo, UT). Participants categorized each leadership and each professionalism attribute as highly important, important, or less important. Participants were able to provide additional comments on the survey. Similar to the first round, all comments provided in the second round were reviewed by the research team and themes were discussed for inclusion in the third round of the Delphi.

Leadership and professionalism attributes that achieved an overall consensus (a priori set to ≥80.0%) of being highly important or important for pharmacy student development were included in the third round of the Delphi. Delphi methodology does not outline a specific consensus threshold, with literature reporting agreement in ranges from 55% to 100%.12 For the purposes of this study, agreement of ≥80.0% was deemed sufficient. Participants rank ordered the leadership attributes by priority of importance for pharmacy student development and were again able to provide comments on the Qualtrics survey. This same approach was used for the professionalism attributes. All comments were reviewed and discussed by the research team. In both of the latter two rounds, participants were able to view the full list of attributes and corresponding definitions as they completed the Delphi (Table 1, Table 2). Agreement frequencies were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Correlations were used to evaluate the differences among groups, with statistical significance defined as p<.05. Analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics, version 26 (IBM Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

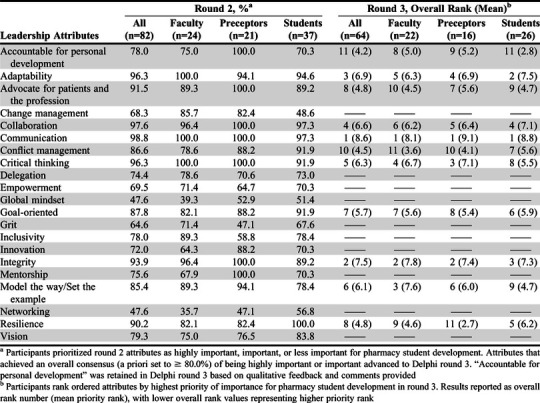

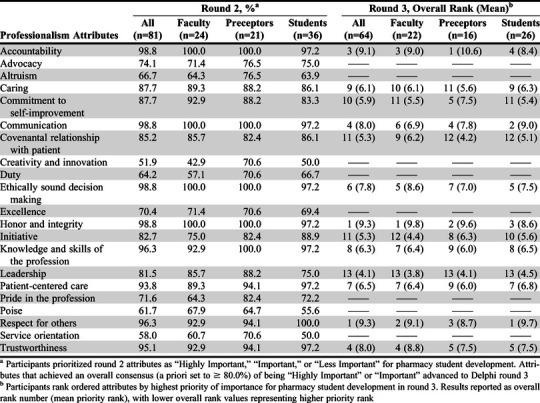

All participants in the first round (N=100) had the opportunity to review and provide feedback on the list of 15 leadership and 20 professionalism attributes. For leadership, eight attributes were added, two were modified, and two were deleted based on detailed discussions of themes identified in participant feedback. For professionalism, two attributes were added, four were modified, and one was deleted based on detailed discussions of themes identified in participant feedback. In the second round, 82% of first round participants (n=82 total: 24 faculty members, 21 preceptors, 37 students) responded to the survey and categorized the 21 leadership attributes (Table 3). Furthermore, 81% (n=81) of first round participants (24 faculty members, 21 preceptors, 36 students) categorized the 21 professionalism attributes (Table 4). Ten leadership and 13 professionalism attributes achieved an overall consensus (a priori set to ≥80.0%) of being highly important or important for pharmacy student development. One additional leadership attribute (ie, accountable for personal development) was retained after reviewing qualitative comments provided in the second round. In total, 11 leadership and 13 professionalism attributes were advanced to the third round. All participants from the second round (n=82) were invited to participate in the third round. Of these, 78% (n=64; 22 faculty members, 16 preceptors, 26 students) completed the third and final round of the modified Delphi (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Leadership Attributes’ Delphi Round 2 and Round 3 Results for Faculty, Preceptor, and Student Participants

Table 4.

Professionalism Attributes’ Delphi Round 2 and Round 3 Results for Faculty, Preceptor, and Student Participants

Correlations were observed between stakeholder groups when analyzing leadership and professionalism attribute ratings within the second and third rounds. Specific to leadership, in the second round, faculty member ratings of highly important and important leadership attributes strongly correlated with preceptor (r=0.68, p<.005) and student ratings (r=0.72, p<.005), while preceptor ratings strongly correlated with student ratings (r=0.59, p<.005). In the third round, faculty rankings of leadership attributes correlated significantly with preceptors (r=0.83, p<.005), while student rankings of leadership attributes were not significantly correlated with those of faculty members (r=0.51, p>.05) or preceptors (r=0.53, p>.05). Specific to professionalism, in the second round, faculty ratings of highly important and important professionalism attributes strongly correlated with preceptor (r=0.90, p<.005) and student ratings (r=0.90, p<.005), while preceptor ratings strongly correlated with student ratings (r=0.92, p<.005). In the third round, faculty rankings of professionalism attributes strongly correlated with preceptors (r=0.77, p<.005) and student ratings (r=0.84, p<.005), while preceptor ratings strongly correlated with student ratings (r=0.80, p<.005).

While these correlations suggest that most leadership and professionalism attributes were rated similarly among stakeholder groups, differences were observed for some attributes (Table 3, Table 4). For example, in the second round, “accountable for personal development” was endorsed as a highly important or important leadership attribute by 75.0% of faculty members, 100.0% of preceptors, and 70.3% of students. Similarly, differences were observed for the leadership attributes of change management (85.7% faculty, 82.4% preceptors, 48.6% students), grit (71.4% faculty, 47.1% preceptors, 67.6% students), and mentorship (67.9% faculty, 100.0% preceptors, 70.3% students) (Table 3). Differences among stakeholder groups was also observed for the professionalism attributes of creativity and innovation (42.9% faculty, 70.6% preceptors, 50.0% students) and service orientation (60.7% faculty, 70.6% preceptors, 50.0% students) (Table 4).

In the third round, the top four ranked leadership attributes were rated similarly across stakeholder groups, with “communication” ranking as the top leadership attribute (faculty rank #1, preceptors #1, students #1) followed by “integrity” (faculty #2, preceptors #2, students #3), “adaptability” (faculty #5, preceptors #4, students #2), and “collaboration” (faculty #6, preceptors #5, students #4). Differences among stakeholder leadership attribute rankings were observed for “conflict management” (faculty #11, preceptors #10, students #7), “model the way/set the example” (faculty #3, preceptors #6, students #9), and “resilience” (faculty #9, preceptors #11, students #5) (Table 3).

Similar to leadership, in the third round, the five top-ranked professionalism attributes were rated similarly across stakeholder groups, with honor and integrity (ranked #1 by faculty members, #2 by preceptors, and #3 by students) and respect for others (ranked #2 by faculty members, #3 by preceptors, #1 by students) tying as the overall top leadership attribute, followed by accountability (ranked #3 by faculty members, #1 by preceptors, #4 by students) then communication (ranked #6 by faculty members, #4 by preceptors, and #2 by students) and trustworthiness (ranked #4 by faculty members, #5 by preceptors, and #5 by students). Differences among stakeholder professionalism attributes rankings were observed for the attributes commitment to self-improvement (ranked #11 by faculty, #5 by preceptors, #11 by students) and initiative (#12 by faculty members, #8 by preceptors, #10 by students) (Table 4).

Comparing stakeholder groups, the difference in mean priority rank was more variable across leadership attributes compared to professionalism attributes. The largest difference in priority rank of leadership attributes was observed for resilience (difference in mean priority rank of 3.5), model the way/set the example (difference of 2.9), and accountable for personal development (difference of 2.4) (Table 3). The largest difference in mean priority rank of professionalism attributes was observed for accountability (difference of 2.2), communication (difference of 2.1), and covenantal relationship (difference of 2.0) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This study is among the first to describe a process for identifying and building consensus on priority leadership and professionalism attributes for pharmacy student development across multiple stakeholders involved in the student learning experience. While there is consensus that leadership and professionalism are important skills necessary for pharmacy practitioners,6,9,13-15,25-27 the literature suggests that how individuals define these characteristics may vary.8,13-15 While Standards 2016 lacks specificity on the attributes important for developing leadership and professional competency,6 these study findings can be used by the Academy to further define these affective domains. Additionally, programs may consider replicating this Delphi process to prioritize leadership and professionalism attributes within their program.

Although Standards 2016 broadly defines these educational outcomes,6 how educators interpret these outcomes may vary depending on their priorities, values, expectations, and experiences. These results support this and suggest that more variance may exist in how individuals define leadership compared to professionalism. This finding expands on the work completed by Reed and colleagues, which found that definitions for leadership in pharmacy varied considerably.8 Reflecting on this finding poses future research questions. For example, is professionalism more centrally agreed upon because of key elements embedded within the Oath of a Pharmacist?28 More research is needed to further investigate this finding.

Results from this study indicate that there is general consensus among faculty members, preceptors, and students on the top priority leadership and professionalism attributes important for pharmacy student development. More specifically, priority professionalism attributes correlated highly across all stakeholder groups throughout the Delphi, and the overall top five rated professionalism attributes all ranked within the top four attributes for each stakeholder group. Further, the overall top four rated leadership attributes all ranked within the top six attributes for each stakeholder group. This level of agreement suggests there is consensus among different stakeholder groups on the top leadership and professionalism attributes important for pharmacy student development.

While correlations between faculty members and preceptor priority leadership attributes remained robust for the second and third rounds, student correlations with faculty member and preceptor rankings did not. Differences were observed among the groups for multiple leadership and professionalism attributes. These findings pose multiple questions about the implications of this research. First, should input from all participant groups be weighted equally in determining priority leadership and professionalism attributes for pharmacy student development? Faculty, preceptor, and student stakeholders were intentionally selected as these groups represent three unique experiences within the student learning environment: didactic coursework (faculty members), experiential education (preceptors), and the cocurriculum (students). When evaluating leadership and professionalism throughout these experiences, for example, should faculty ratings and priorities be weighted more heavily when evaluating leadership and professionalism within didactic coursework, preceptor ratings and priorities more heavily during experiential rotations, and/or student ratings and priorities more heavily within the cocurriculum? Second, do variations in attribute priorities reflect variations in setting opportunities and/or setting expectations? For example, is “model the way/set the example” a more important or more commonly used skill in academia (faculty members) compared to clinical practice (preceptors) and/or the cocurriculum (students)? Is “commitment to self-improvement” a more important or more commonly used skill in clinical practice (preceptors) compared to in the didactic curriculum (faculty members/students), cocurriculum (students), academia (faculty members), and/or student organizations (students)? Future research is needed to investigate these questions.

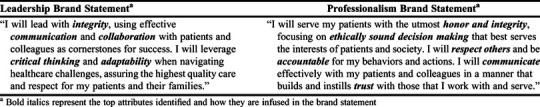

In efforts to integrate these priority leadership and professionalism attributes throughout the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy PharmD program (eg, didactic curriculum, experiential education, cocurriculum), leadership and professionalism brand statements were created using the top attributes identified through the modified Delphi. The leadership brand statement incorporates the top five leadership attributes identified (ie, adaptability, collaboration, communication, critical thinking, integrity), while the professionalism brand statement incorporates the top six professionalism attributes identified (ie, accountability, communication, ethically sound decision making, honor and integrity, respect for others, trust) (Table 5). The purpose of these brand statements is to focus the school’s leadership and professionalism content, and thus expectations, throughout the various student learning experiences on the priority attributes identified by faculty members, preceptors, and students. While these priority attributes and brand statements do not encompass all leadership and professionalism attributes important for various professional pharmacy settings, the statements represent attributes that will be embodied by the pharmacy leader and professional graduating from the PharmD program. Thus, these brand statements were reviewed and endorsed by the PharmD Curriculum and Assessment Committee for inclusion in all relevant syllabi and coursework. Additionally, students are introduced to these brand statements during new student orientation. While these brand statements focus the leadership and professionalism content emphasized throughout the PharmD program, broader literature should be consulted regarding how best to effectively teach these competencies.

Table 5.

Leadership and Professionalism Brand Statements Created Using the Top Attributes Identified in the Delphi

Although prior professionalism research in pharmacy has indicated the importance of exhibiting professionalism attributes through role modeling,29 the impact of a professionalism brand statement related to one’s behavior and perceptions regarding professionalism needs to be investigated. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of brand statements on both leadership and professionalism development in pharmacy students. Further, modeling is acknowledged as one of the most effective means of teaching professionalism within both the actual and any “hidden” curricula that may exist.26 More research is needed to determine what effect having explicit leadership and professionalism brand statements has on role modeling. Further, as many of the attributes are applicable to multiple health professions, brand statements could be used as part of professionalism and/or leadership activities designed to strengthen interprofessional collaboration and education.30,31

While this study was effective at identifying and prioritizing leadership and professionalism attributes for pharmacy student development among faculty members, preceptor, and student groups, it was conducted at a single institution with volunteer expert faculty member, preceptor, and student participants. Additionally, attrition between rounds may be associated with nonresponse bias. Although this Delphi methodology can easily be implemented at other institutions, specific leadership and professionalism priorities may vary to reflect differences in curricular practices, experiential education, and/or cocurricular activities. However, the inclusion of preceptors in this study may have improved the generalizability of these findings as preceptors represent the pharmacy workforce and often precept for multiple schools and colleges of pharmacy. Next steps in this work include integrating the priority attributes throughout the PharmD curriculum and determining the assessment criteria and strategy for evaluating these priority leadership and professionalism attributes across the student learning environment (didactic, experiential, cocurriculum).

CONCLUSION

The modified Delphi technique can effectively identify and prioritize leadership and professionalism attributes important for pharmacy student development. This process facilitates consensus building and identifies gaps among stakeholders (ie, faculty members, preceptors, students). Identified gaps may represent varying priorities among stakeholders and/or different opportunities for emphasis and development across educational settings (eg, didactic, experiential, cocurriculum).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy Leadership and Professional Development course stream members who advised on the implementation of this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams ML, Blouin RA. The role of the pharmacist in health care: expanding and evolving. N C Med J. 2017; 78(3):165-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Informing the Future: Critical Issues in Health. 6th ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albanese NP, Rouse MJ, Schlaifer M. Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Scope of contemporary pharmacy practice: roles, responsibilities, and functions of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2010;50(2):e35-e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerr RA, Beck DE, Doss J, et al. Building a sustainable system of leadership development for pharmacy: report of the 2008-09 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ . 2009;73(8):Article S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley-Baker LR, Murphy NL. Leadership development of student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):219. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree: standards 2016https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2020.

- 7.Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, et al. Core principles & values of effective team-based health care. NAM Perspectives . 2012; Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC: https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/VSRT-Team-Based-Care-Principles-Values.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed BN, Klutts AM, Mattingly TJ. A systematic review of leadership definitions, competencies, and assessment methods in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ . 2019;83(9):Article 7520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janke KK, Traynor AP, Boyle CJ. Competencies for student leadership development in doctor of pharmacy curricula to assist curriculum committees and leadership instructors. Am J Pharm Educ . 2013;77(10):Article 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Traynor AP, Boyle CJ, Janke KK. Guiding principles for student leadership development in a doctor of pharmacy program to assist administrators and faculty members in implementing or refining criteria. Am J Pharm Educ . 2013;77(10):Article 221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traynor AP, Borgelt L, Rodriguez TE, Ross LA, Schwinghammer TL. Use of a modified Delphi process to define the leadership characteristics expected of pharmacy faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ . 2019;83(7):Article 7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(4):376-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beardsley R, Benner J, Alter R, et al. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism: recommendations of the American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy and American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans Task Force on Professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40(1):96-102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Morgan JA, Rodriguez de Bittner M. Professionalism: a determining factor in experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ . 2007;71(2):Article 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ . 2003;67(3):Article 96. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox ER, Krueger KP, Murphy JE. Pharmacy student involvement in student organizations. J Pharm Teach. 1998;6(3):9-18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel UJ, Mediwala KN, Smith KM, Taylor S, Romanelli F. Carpe diem! Seizing the rise of co-curricular experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(8):Article 6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott MA, McLaughlin J, Shepherd G, Williams C, Zeeman J, Joyner P. Professional organizations for pharmacy students on satellite campuses. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(5):Article 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeeman JM, Bush AA, Cox WC, Buhlinger K, McLaughlin JE. Identifying and mapping skill development opportunities through pharmacy student organization involvement. Am J Pharm Educ . 2019;83(4):Article 6950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeeman JM, Bush AA, Cox WC, McLaughlin JE. Assessing the co-curriculum by mapping student organization involvement to curricular outcomes using mixed methods. Am J Pharm Educ . 2019;83(10):Article 7354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH, Gustafson DH. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Co. 1975:10,89. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, Brook RH. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health . 1984;74(9):979-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs . 2000;32(4):1008-1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu CC, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(10):1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. The Leadership Challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth MT, Zlatic TD. Development of student professionalism. Pharmacotherapy . 2009;29(6):749-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janke KK, Nelson MH, Bzowyckyj AS, Fuentes DS, Rosenberg E, DiCenzo R. Deliberate integration of student leadership development in doctor of pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ . 2016;80(1):Article 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Pharmacists Association. Oath of a Pharmacist. https://www.pharmacist.com/oath-pharmacist. Accessed October 22, 2020.

- 29.Thompson DF, Farmer KC, Beall DG, et al. Identifying perceptions of professionalism in pharmacy using a four-frame leadership model. Am J Pharm Educ . 2008;72(4):Article 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnold L, Cuddy PG, Hathaway SB, Quaintance JL, Kanter SL. Medical school factors that prepare students to become leaders in medicine. Acad Med . 2018;93(2):274-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNair RP. The case for educating health care students in professionalism as the core content of interprofessional education. Med Educ. 2005;39:456-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]