Abstract

Objective. To determine student pharmacists’ perceptions of a leadership development program for student organization officers and report the changes in their Emotional Intelligence Appraisal (EIA) scores.

Methods. Between 2015-2018, three different cohorts of Doctor of Pharmacy students participated in a voluntary leadership development program that spanned six academic quarters. The program included a variety of self-assessments and large-group topic discussions, followed by quarterly individual written reflections with feedback from faculty mentors. These activities primarily addressed the topics of emotional intelligence, strengths-based leadership, and continuous leadership development. Participants’ EIA scores near the beginning and end of the program were compared. An anonymous online survey of participant perceptions was administered at the end of the program.

Results. One hundred sixty-six student pharmacists completed all program activities. Each cohort’s final mean overall, self-awareness, self-management, and social awareness EIA scores were higher than their corresponding mean initial scores. The overall response rate for the online survey was 61%. All respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that participating in the program enhanced their leadership skills. The majority of respondents additionally rated each of the program’s activities as being either beneficial or very beneficial. The emotional intelligence assessment and strengths-based leadership assessment were the activities that were most frequently cited as being very beneficial.

Conclusion. The pilot implementation of this leadership development program appears to have been both impactful and well received. Programs structured like this one may provide an effective way of increasing the emotional intelligence of student pharmacists, particularly within accelerated pharmacy programs.

Keywords: accelerated pharmacy program, co-curriculum, emotional intelligence, leadership development, student pharmacists, student professional organizations

INTRODUCTION

Fostering the growth of pharmacy students’ leadership skills has been increasingly recognized as an essential component of professional development.1,2 However, a perceived “leadership gap” within the profession currently exists.3 Schools and colleges of pharmacy have been identified as the logical setting for the introduction and reinforcement of leadership principles.4,5 The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy’s Argus Commission has acknowledged leadership as a responsibility for all pharmacists and recommended leadership education on a broad scale, extending beyond traditional management coursework and integrating within extracurricular and co-curricular programs.6

One key component of effective leadership is emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence has been described as a composite of four distinct, but interrelated, skills: self-awareness (accurately perceiving one’s own emotions in the moment and understanding emotional tendencies), self-management (using awareness of one’s emotions to direct behavior positively), social awareness (accurately perceiving and understanding the emotions of others), and relationship management (using emotional awareness to manage interactions successfully).7 Emotionally intelligent leaders are believed to have greater professional resiliency and engage more effectively in interdisciplinary teamwork, leading to success in pharmacy practice.8 Therefore, the concept of emotional intelligence has been incorporated into curricular and co-curricular leadership programming.9-12 Although multiple methods have been proposed for training pharmacy leaders,13 the establishment of formal leadership development programs allows a school to offer diverse activities intended to enhance students’ leadership skills and increase opportunities for reflection. Further, unlike a single didactic course, these programs may span multiple quarters or semesters, allowing students to apply acquired leadership skills as they progress through the curriculum, observe different leadership styles during practice experiences, and participate in various leadership roles.

The success of a leadership development program offered to officers from the American Pharmacists Association-Academy of Student Pharmacists (APhA-ASP) chapter at Midwestern University College of Pharmacy Glendale campus (MWU-CPG) has been described by Raney and Bowman.10 This program was originally created to offset the accelerated nature of MWU-CPG’s three-year Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum, which operates on a year-round, four-quarter system that places greater limitations on the time students have to gain leadership experience while serving as elected officers. While the program successfully expanded officers’ leadership involvement beyond their traditional duties, the reproducibility of these results in a larger sample of pharmacy students was unknown. Thus, the leadership development program was subsequently expanded into a voluntary program open to all student officers and, eventually, to all students at MWU-CPG. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of a multi-modal, longitudinal student leadership development program that primarily targeted student organization officers within an accelerated pharmacy program. The effectiveness of the program was assessed by comparing participants’ Emotional Intelligence Appraisal (EIA) scores at the beginning and end of the program and administering a student perception survey following program completion.

METHODS

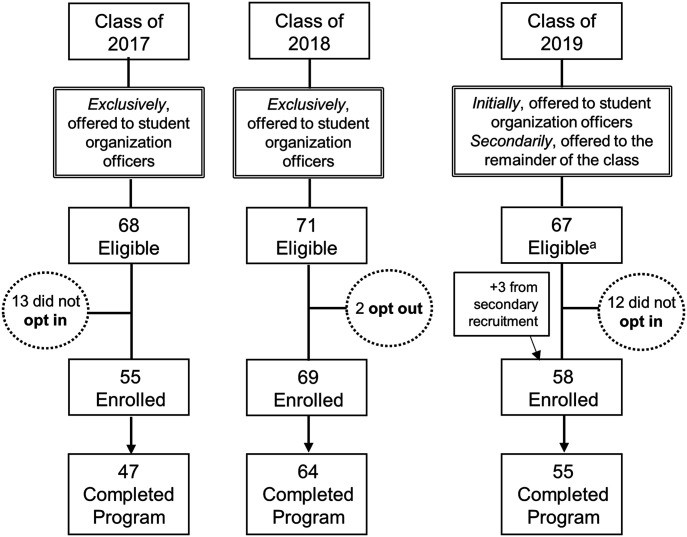

The leadership development program was initially offered to students in the class of 2017 who had been elected to a position within a student organization, a process which typically occurs during the first didactic year. The program was similarly offered to students within the classes of 2018 and 2019; however, the enrollment strategy differed slightly with each cohort (Figure 1). The program consisted a series of activities during each of the subsequent six quarters, concurrent with the student officers’ elected terms. Quarterly activities included readings, self-assessments, large-group topic discussions, and individual written reflections with feedback provided by faculty mentors. These activities addressed topics such as emotional intelligence, strengths-based leadership, team dysfunctions, and continuous leadership development. Eligible students who initially did not choose to participate but subsequently wanted to join were enrolled at the halfway point and required to make-up any previous activities.

Figure 1.

Leadership Development Program Recruitment and Enrollment Results by Cohort

a Per initial eligibility criterion

Discussions were scheduled early in the quarter as one-hour large-group lunch meetings that aimed to expose students to leadership topics. Each discussion was led by members of the program’s oversight committee, which initially consisted of six faculty members and typically used a combination of PowerPoint presentations and active-learning exercises. Subsequent reflection activities, typically due within two weeks, allowed students to directly apply leadership topics to experiences they had as student leaders. Participants submitted completed reflections to a faculty mentor, randomly assigned from the oversight committee. The average mentee:mentor ratio throughout the study was 8:1. Mentors provided feedback on reflections and posed additional questions as needed. Mentee:mentor assignments were maintained throughout the program to provide consistent, longitudinal feedback and develop mentoring relationships. Participants who submitted all required reflections were awarded certificates of completion at a concluding reception. While this development program was ultimately an initiative of the faculty members involved, activities were funded through the Dean’s Office, which also provided administrative support.

To assess program effectiveness, participants’ initial and final EIA scores were compared.14 An overall emotional intelligence score was reported along with scores for each Emotional Intelligence 2.0 skill.7 These scores were established on a scale of 0-100, derived from a “normed” sample, and associated with a particular skill level. Participants’ resulting scores were evaluated in aggregate using descriptive statistics within Excel 2016. Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 8, version 8.2.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA), and consisted of paired, two-tailed, t tests.

An anonymous, voluntary perception survey was administered online following each cohort’s concluding reception using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The survey instrument used a four-point Likert scale to prevent neutral responses, and also included open-ended questions that asked students to indicate how program activities may be improved, suggest additional items for program inclusion, and provide additional feedback or comments. The collected data were evaluated using descriptive statistics within Excel 2016. Students were able to participate in the program independent of their completion of the perception survey. This research fulfilled criteria for expedited review and was approved by the MWU-CPG Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Across all three cohorts, 206 students met the participation requirements and 182 students (88%) participated (Figure 1). Relative to matriculated class size, each cohort’s recruitment rate was 36%, 44%, and 37%, respectively. All student organizations were consistently well-represented with the exception of the Phi Lambda Sigma chapter, which does not elect student officers. Among the participants, 166 students (91%) completed all program activities. Of the 16 students who did not complete the program, nine were no longer eligible because of academic/professional difficulties, two withdrew because of workload beyond the program, and five failed to complete all required assignments. Attrition rates and reasons for attrition were consistent across all cohorts.

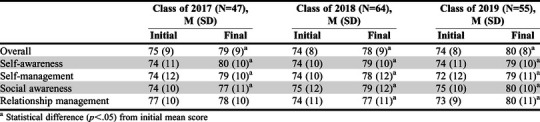

Mean initial and final EIA scores were also consistent across all cohorts (Table 1). In particular, each cohort’s mean overall, self-awareness, self-management, and social awareness final scores were higher than their corresponding mean initial scores (p<.05). With regard to the mean relationship management final scores, only the scores for the class of 2018 and class of 2019 cohorts were statistically higher than their corresponding initial scores.

Table 1.

Pharmacy Students’ Emotional Intelligence Appraisal Scores Before and After Participating in a Leadership Development Program for Student Organization Officers

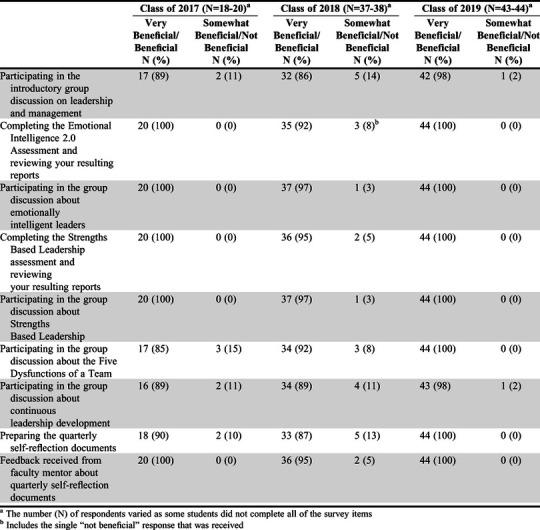

Of the students who completed all program activities, 102 completed the perception survey for an overall response rate of 61% (class of 2017, 43%; class of 2018, 59%; class of 2019, 80%). The variation in yearly response rate was attributed to survey timing relative to course load. All respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that participating in the program enhanced their leadership skills; however, the ratio of strongly agree to agree responses for the class of 2018 cohort (1:1) was comparatively lower than that for the other cohorts (6:1). A majority of respondents from each cohort (85%-100%) also found each program activity to be very beneficial or beneficial to their leadership development (Table 2). However, a disproportionate amount of “somewhat beneficial” responses (69%) and a single “not beneficial” response were found among the class of 2018 cohort. Taking the Strengths-Based Leadership Assessment and the Emotional Intelligence 2.0 assessment were consistently noted as the most beneficial activities.

Table 2.

Pharmacy Students’ Responses to a Survey Regarding Activities Included in a Leadership Development Program for Student Organization Officers

Sixty-nine percent of respondents (70/102) provided feedback for program improvement. Forty-five percent of unique comments (38/84) referred to adding small group or individual discussions to further apply the program’s topics to the participant’s leadership experiences. The next most prevalent themes identified were the recommendation to include more active-learning exercises (8/84) and the recommendation to incorporate more real-life examples (5/84). A total of 25 replies were provided when asked for any additional comments, virtually all of which were positive and complimentary.

DISCUSSION

This was the largest reported study evaluating the impact of a multi-modal, longitudinal leadership development program targeted toward student organization officers within an accelerated pharmacy program. The results of the study indicate that the program positively impacted participants’ overall emotional intelligence. This impact is similar to that demonstrated by an earlier pilot study of APhA-ASP officers completing a leadership development program with the same topic structure.10 In addition, Smith and colleagues found a significant increase in mean overall EIA scores for 38 pharmacy students participating in an optional three-year leadership degree program at the University of Oklahoma.9 Although the program reported by Smith and colleagues was focused on a didactic and experiential curriculum rather than extracurricular leadership activities, it similarly incorporated activities focused on areas of emotional intelligence.9 However, no comparable initiatives among accelerated pharmacy curricula have been reported, which present several distinctive challenges. In addition to a year-round increase in faculty responsibilities, the program places an additional workload on students, who already have a very full schedule. Therefore, several purposeful considerations were made to mitigate this workload, including scheduling a majority of program activities for early in the quarter, holding group topic discussions as lunch meetings with food provided, and allowing students multiple weeks to prepare for the discussions and complete subsequent reflection activities.

A consistent positive impact on EIA scores was seen across all three cohorts, regardless of enrollment strategy. However, the lower rate of program satisfaction among students in the class of 2018 may have been influenced by the opt-out enrollment strategy. While the program was voluntary, participants’ motivation to actively enroll (opt-in) may represent a conscious effort to engage in program activities and perceive more positive outcomes of the program. While a certificate of completion was awarded to participants, other tangible benefits such as course credit were not available. The change in enrollment strategy for the class of 2018 cohort was made to ease the administrative burden of the recruitment process while potentially expanding the program’s cohort. Although this was not a study objective, the resulting observations are worth considering for future offerings of the program. In addition, the program was not initially offered to all students because of limited resources, particularly the limited number of faculty mentors.

There are several limitations to this study that should be recognized and may present opportunities for future study. First, the results of this study characterize findings at a single college of pharmacy and may not be representative of experiences at other institutions. In addition, because program participants consisted almost entirely of student organization officers, potential selection bias may have occurred with the perception survey results. While the program may have contributed to improved emotional intelligence, each student had additional professional and/or personal experiences that likely influenced their EIA scoring, either positively or negatively. In addition, the practical significance of these changes is unknown, as most post-scores remained within the “with a little improvement, this could be a strength” skill level.7,13 Furthermore, the EIA instrument represents only one theoretical model of emotional intelligence and does not incorporate third-party viewpoints. Despite these limitations, the current study provides valuable insights for others attempting to develop the leadership skills of student pharmacists, particularly among accelerated pharmacy curricula, thereby helping to close the perceived “leadership gap” within the pharmacy profession.3 These insights have also helped guide the authors’ own improvement efforts. For example, the program’s first group discussion has been revised to include an initial meet-and-greet between individual faculty mentors and their mentee as well as some small group activities. Also, the recruitment approach has been changed to a full class opt-in at the start of the program in order to further simplify enrollment and minimize the number of secondary recruits.

CONCLUSION

Three cohorts of participants in the MWU-CPG leadership development program experienced a significant improvement in emotional intelligence scores. The program was well-received by participants, who identified the benefits of the program in terms of their personal leadership development. Overall, this study provides a potential model for a longitudinal leadership development program for pharmacy students as well as other health professions students.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Lindsay Davis, PharmD, Alyssa Peckham, PharmD, Joie Rowles, PhD, and Tara Storjohann, PharmD, for their contributions in creating, maintaining, and/or delivering the described program, as well as the MWU-CPG Dean’s Office for their financial and administrative support.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on professionalism. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/policy-guidelines/docs/statements/professionalism.ashx. Accessed November 3, 2020.

- 2.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on leadership as a professional obligation. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/policy-guidelines/docs/statements/leadership-as-professional-obligation.ashx. Accessed November 3, 2020.

- 3.White SJ. Will there be a pharmacy leadership crisis? an ASHP foundation scholar-in-residence report. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005;62(8):845-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. . Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) educational outcomes 2013. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. “Standards 2016” https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerr RA, Beck DE, Doss J, et al. . Building a sustainable system of leadership development for pharmacy: report of the 2008-09 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradberry T, Greaves J. Emotional Intelligence 2.0. San Diego, CA: TalentSmart, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward A, Hall J, Mutch J, et al. . What makes pharmacists successful? an investigation of personal characteristics. J Am Pharm Assoc . 2019;59(1):23-29.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith MJ, Wilson J, George DL, et al. . Emotional intelligence scores among three cohorts of pharmacy students before and after completing the University of Oklahoma College of Pharmacy's Leadership Degree Option Program. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(7):911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raney E, Bowman B. Developing emotionally intelligent leaders within a chapter of a student pharmacist organization. MedEdPublish. 2018;7(4):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson MH, Fierke KK, Sucher BJ, et al. . Including emotional intelligence in pharmacy curricula to help achieve CAPE outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(4):Article 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haight RC, Kolar C, Nelson MH, et al. . Assessing emotionally intelligent leadership in pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(2)Article 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janke KK, Nelson MH, Bzowyckyj AS, et al. . Deliberate integration of student leadership development in doctor of pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(1):Article 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TalentSmart Inc. Emotional Intelligence Appraisal Technical Manual. https://www.talentsmart.com/media/uploads/pdfs/technical-manuals/Emotional%20Intelligence%20Appraisal%20-%20Technical%20Manual.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2020.