Abstract

Meteorological parameters are the critical factors of affecting respiratory infectious disease such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and influenza, however, the effect of meteorological parameters on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains controversial. This study investigated the effects of meteorological factors on daily new cases of COVID-19 in 127 countries, as of August 31 2020. The log-linear generalized additive model (GAM) was used to analyze the effect of meteorological variables on daily new cases of COVID-19. Our findings revealed that temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed are nonlinearly correlated with daily new cases, and they may be negatively correlated with the daily new cases of COVID-19 over 127 countries when temperature, relative humidity and wind speed were below 20°C, 70% and 7 m/s respectively. Temperature(>20°C) was positively correlated with daily new cases. Wind speed (when>7 m/s) and relative humidity (>70%) was not statistically associated with transmission of COVID-19. The results of this research will be a useful supplement to help healthcare policymakers in the Belt and Road countries, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to develop strategies to combat COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Temperature, Relative, Humidity, Wind speed

Highlights

-

•

Temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed were nonlinearly correlated with daily new cases.

-

•

We used log-linear GAM to analyze the effects.

-

•

First study to explore the effects of meteorological factors on the daily new cases of COVID-19 in 127 "Belt and Road" countries.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a novel Coronavirus subtype (Zhu et al., 2020) (which was later named SARS-COV-2 (Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of, 2020) by the International Committee on Virus Classification, and WHO named pneumonia caused by this virus “COVID-19″) first detected in Wuhan, China, then COVID-19 pandemic has swiftly spread all over the world and have become a global public health crisis. This is also the third time (after SARS-COV and MERS-CoV) that the world has seen a global epidemic caused by a subtype of coronavirus in the last two decades (Chen et al., 2020). On January 30, 2020, WHO announced that this novel coronavirus outbreak was a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), which was the highest alert level of WHO(WHO, 2020c). On March 11, the outbreak was declared a pandemic by the WHO(Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020). The epidemic has had devastating consequences on human health, lives and economies. More than 23 million new cases and more than 800,000 deaths have been reported in 216 countries worldwide as of August 31, 2020(WHO, 2020b), and the number of new cases and deaths was still increasing.

Seasonality is a long-recognized attribute of many viral infections of humans(Fisman, 2012; Heikkinen and Järvinen, 2003). Meteorological factors such as temperature and humidity are important factors causing seasonal changes in the infection of respiratory virus (Kutter et al., 2018; Paynter, 2015; Pica and Bouvier, 2012). Sufficient epidemiological studies and laboratory studies have proved that meteorological conditions are essential factors affecting the survival and transmission of coronavirus(Bi et al., 2007; Chan et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2006; Pica and Bouvier, 2012; van Doremalen et al., 2013). However, conclusions about the effect of meteorological factors on COVID-19 transmission are still controversial(Bashir et al.; Gunthe et al., 2020; J. Liu et al.; Neher et al., 2020; Pani, Lin, & RavindraBabu; Yao et al.). Several recent studies have investigated the impact of meteorological factors on the spread of COVID-19 around the world(Biktasheva, 2020; Kodera et al., 2020; J.Liu et al., 2020b; Méndez-Arriaga, 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Rouen et al., 2020; Şahin, 2020; Shi et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Xie and Zhu, 2020), but there has not been enough evidence to indicate that meteorological factors are the critical regulators of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 so far. WHO also pointed out that a lot of research was still needed to improve prediction models and take public health measures(Smit et al., 2020). Therefore, investigating the weather dependence of COVID-19 in different regions or countries is very important to enhance the current understanding of its spread.

The joint construction of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (hereinafter referred to as “Belt and Road”) is a major initiative put forward by China, which has attracted great attention from the international community. By the end of January 2020, China had signed 200 cooperation documents with 138 countries and 30 international organizations to jointly build the " Belt and Road"(Portal, 2019). With the global outbreak of the pandemic, most of the “Belt and Road” countries have been battered, and some related projects have also been affected to varying degrees (Chen and Yang, 2020). The accelerated economic development of the countries along the " Belt and Road”, convenient transportation, frequent movement of people and expanding international trade have created opportunities for the rapid spread of infectious diseases. The COVID-19 epidemic proves that we are only “one plane away” from any new and sudden outbreak of infectious diseases. The spread of infectious diseases is a major threat and serious challenge to public health under the Belt and Road initiative. There are differences in the level of development of the “Belt and Road” countries, and their medical and health conditions and epidemic prevention and control policies are different. As the “Belt and Road” cooperation projects gradually resume their smooth operation, the flow of people and goods between countries will continue to increase.

To date, no comprehensive study of climate impacts on covid-19 has been reported within the One Belt And One Road geographic area. Therefore, investigations of COVID-19's weather dependency in “Belt and Road” countries are important to enhance the present understanding about its spread. Therefore, in this study, we intended to investigate the correlation between climatic factors and the number of daily new cases in each country over a period of 8 months using Generalized Additive Model (GAM). The main objective is to examine the scientific evidence of climate dependence for transmission of COVID-19 cases in Belt and Road, depending on climatic conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

There are a total of 138 ″Belt and Road” countries (not including China) that have signed cooperation documents with China to jointly build the “Belt and Road” as of August 31, 2020(Portal, 2019). Among them, eight countries and regions including Samoa, Niue, Federated States of Micronesia, Cook Islands, Tonga, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, and Kiribati did not report epidemic data of COVID-19, and daily meteorological data of 4 countries including Barbados, Lesotho, South Sudan and Yemen are not provided on the website of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration(NOAA), so they were excluded from the study. The remaining 127 countries (including China) that reported new cases of COVID-19 to WHO as of August 31, 2020 were included in the study (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

127 countries included in the study and their continents.

| Continent | Number of countries | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 42 | Angola, Burundi, Benin, Cote d'Ivoire, Cameroon, Congo, Comoros, Cape Verde, Djibouti, Algeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Gambia, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Libya, Morocco, Madagascar, Mali, Mozambique, Mauritania, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sudan, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Seychelles, Chad, Togo, Tunisia, Tanzania, Uganda, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe |

| Asia | 37 | Afghanistan, United Arab Emirates, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bahrain, Brunei, China, Georgia, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Cambodia, South Korea, Kuwait, Laos, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Myanmar, Mongolia, Malaysia, Nepal, Oman, Pakistan, Philippines, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Thailand, Tajikistan, Timor, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Vietnam |

| Europe | 27 | Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Belarus, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Moldova, Macedonia, Malta, Montenegro, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Ukraine |

| North America | 10 | Antigua and Barbuda, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Jamaica, Panama, El Salvador, Trinidad and Tobago, |

| South America | 8 | Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela |

| Oceania | 3 | Fiji, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea |

2.2. Data collection

Data, including daily new cases in 127 countries, were collected from the World Health Organization various daily situation reports (Hasell et al., 2020), as of August 31, 2020(WHO, 2020a). Daily meteorological data during the same study period of each country, including daily average temperature, average dew point and average wind speed were obtained from the website of NOAA(NOAA, 2020). Daily meteorological data of monitoring stations nearest to each country's capital were used.

2.3. Calculation of relative humidity

Relative humidity (RH) is the ratio of the absolute humidity in the air to the saturated absolute humidity at the same temperature and pressure. The calculation formula is as follows:

| (1) |

In equation(1), RH donates the relative humidity, E(hPa) donates the actual vapour pressure, Ew(hPa) donates the saturated vapour pressure of pure horizontal liquid level (or ice surface) corresponding to the dry-bulb temperature t (°C).

The dew point temperature refers to the temperature at which the air is cooled to saturation when the water vapour content and air pressure do not change. The actual vapour pressure E and the saturated vapour pressure Ew can be calculated from the dew point temperature and the actual temperature respectively by adopting the modified Magnus formula(Wu et al., 2020), the formula is as follows:

| (2) |

In equation (2), E0 denotes saturation vapour pressure at a reference temperature T0(273.15 K) which equals 6.11 Mb, a is a constant of 17.43 and B is a constant of 240.73.t(°C) is the actual temperature or dew point.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The GAM is a combination of the generalized linear model and the additive model. It uses a connection function to establish the relationship between the expectation of the response variable and the nonparametric predictor variables(Peng et al., 2006; Talmoudi et al., 2017). In this study, a log-linear GAM was used to analyze the associations between meteorological factors and daily new cases of COVID-19(Dominici et al., 2006). Compared to the total population of 127 countries, the incidence of daily COVID-19 infection among individuals is extremely low, and the distribution is similar to Poisson distribution.

In looking at the effect of temperature and relative humidity on the number of daily new cases, some confounding factors need to be controlled for. The number of daily new cases may always be higher on one day of the week than on the other, so it is necessary to control the day of the week effect. In addition, we used the natural smooth spline function to fit the long-term trend of the time, and determine the degrees of freedom of time trend based on AIC law(Gasparrini, 2014). The model was defined as follows:

| (3) |

In formula (3), log(Yt) is the log-transformed of the number of COVID-19 daily new cases on dayt (added one to avoid taking the logarithm of zeros); α is the intercept; TEMt is the average temperature on dayt; RHt is the average relative humidity on dayt, Windt is the average wind speed on dayt; s() refers to a thin plate spline function, which is based on the penalized smoothing spline(K.Liu et al., 2020c); Countryi is a categorical variable for country; DOW is a categorical variable indicating the date of the week; dayt is the number of days appearing COVID-19 cases in Countryi for capturing day fixed effect; df is the degree of freedom.

Because the effect of weather factors could last for several days and the incubation period of COVID-19 ranges from 1 day to 14 days(National, Health and Commission, 2020), we also examined the associations with different lag structures, including both single-day lag (lag1, lag3, lag7 and lag14) and cumulative lag(lag01,lag03, lag 07 and lag 014). In single-day lag models, a lag of 1 day (lag1) refers to weather indicator on the previous day; in cumulative lag models, lag014 corresponds to a 15-day moving average of weather factors of the current and previous 14 days.

According to the results from the GAMs, then we used a piecewise linear regression to determine the relationship between meteorological factors and COVID-19 confirmed cases(Xie and Zhu, 2020). In the sensitivity analysis, we excluded Chile, South Africa, Peru and Russia because the number of confirmed cases was much larger than that of other countries.

In this study, GAMs in our analysis were implemented via the “mgcv” package (version 1.8–28) of R software (version 3.5.2). The statistical tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analysis

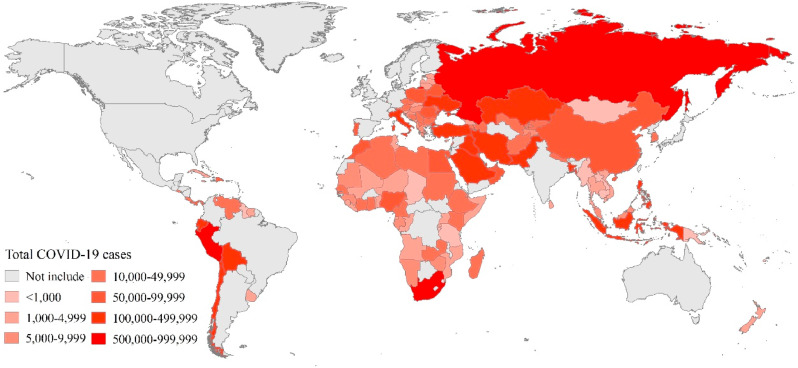

A total of 7,892,264 new cases had been documented in the 127 countries in the study as of August 31, 2020. The distribution of confirmed cases are shown in Fig. 1 . Russia (990,326 cases), Peru (647,166 cases) and South Africa (625,056 cases) were the three countries with the most confirmed cases.

Fig. 1.

The total number of cases of COVID-19 in the study area as of 31 August 2020.

We recorded an average daily count of confirmed cases of 343 in 127 countries. The mean value of temperature, relative humidity and wind speed was 20.5°C, 66.54%, and 1.94 m/s, respectively (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of daily new cases and meteorological variables across all countries and days as of August 31, 2020.

| Mean | SD | MAX | MIN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily new cases | 343 | 1060 | 36179 | 0 |

| Temperature(°C) | 20.5 | 12.4 | 42.9 | −17.8 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 66.54 | 20.17 | 100.00 | 5.31 |

| Wind speed (m/s) | 3.2 | 1.7 | 17.6 | 0.0 |

3.2. Correlation analysis

3.2.1. Spearman ranks correlation analysis

The results of our preliminary correlation analysis shows in Table 3 . We found that temperature (°C)(r = −0.113,p < 0.001), relative humidity(%) (r = 0.195,p < 0.001) and wind speed (m/s) (r = −0.010,p < 0.01) all were significantly negatively correlated with daily new cases of COVID-19 in 127 countries.

Table 3.

Spearman correlation coefficients between meteorological variables and growth rate across all countries and days.

| Meteorological Indices | Daily new cases |

|

|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | P-value | |

| Temperature (°C) | −0.113 | <0.001 |

| Relative Humidity (%) | −0.195 | <0.001 |

| Wind Speed (m/s) | −0.010 | <0.001 |

3.2.2. Analysis of generalized additive model

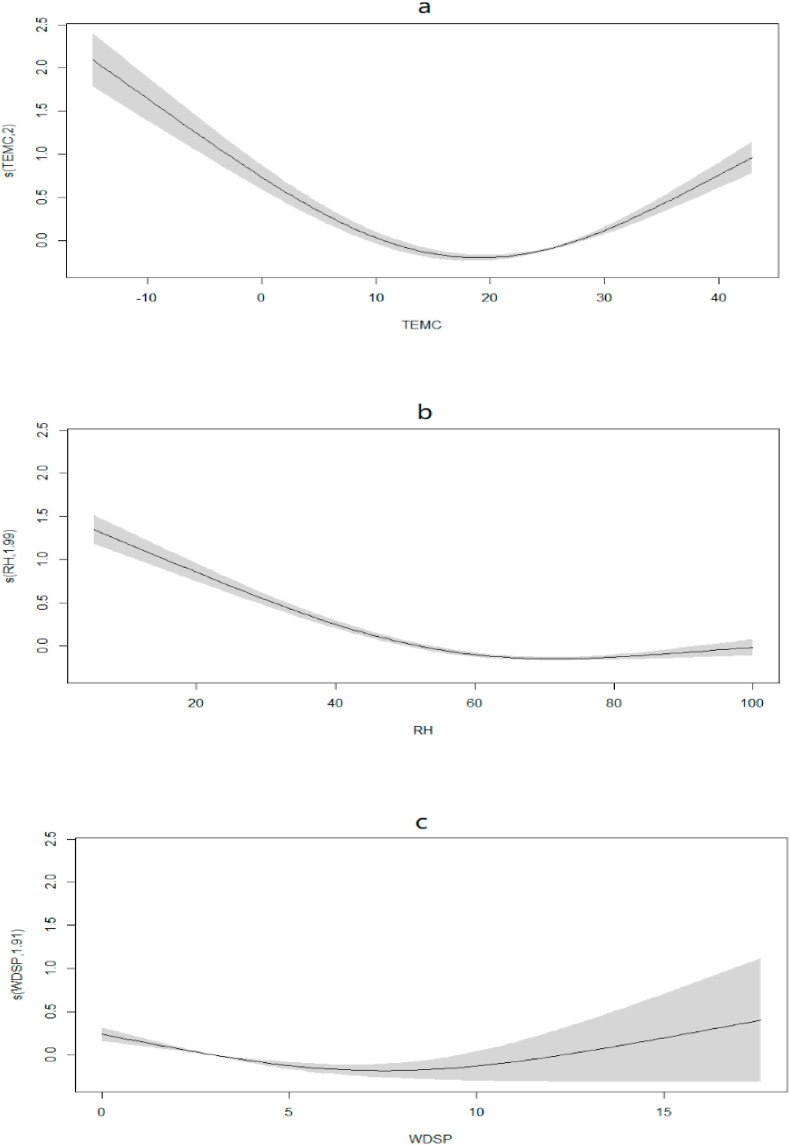

To estimate the exact structural influence of climatic conditions for the spread of COVID-19 in 127 countries, we proceed to estimate the magnitude of the effect of these meteorological factors on the transmission of COVID-19 using GAM. The exposure-response curves in Fig. 2 suggested that the relationship between meteorological variables and daily new cases of COVID-19 cases was significantly nonlinear (Temperature: p < 0.001, RH: p < 0.001, WDSP: p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Exposure-response curves for the effects of meteorological variables on daily new cases of COVID-19. The x-axis is the meteorological parameters. The y-axis indicates the contribution of the smoother to the fitted values.

3.2.2.1. Relationship between temperature and COVID-19

The exposure-response curves in Fig. 2(a) suggested that the correlation between temperature and daily new cases of COVID-19 was non-linear (p < 0.001). Specifically, temperature is significantly negatively correlated with daily new cases in the range of<20°C, while the correlation reversed above 20 °C.

Based on results from GAM, a piecewise linear regression was adapted with a threshold at a 20°C. Table 4 shows the effect of temperature at different layers on new daily cases after stratification. A 1°C increase in temperature, the number of daily new cases decreased by 5.45% (95%CI: 4.34%–6.57%) when the temperature was below 20°C. When the temperature was above 20°C, for every 1°C increase in temperature, the number of daily new cases increased by 11.07% (95%CI: 10.10%–12.05%).

Table 4.

The effects of a 1 °C increase in temperature on daily new cases of COVID-19.

| Temperature (°C) | Daily new cases |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | 95%CI |

P | ||

| Upper limit | Lower limit | |||

| ≤20 | −5.45% | −4.34% | −6.57% | <0.001 |

| >20 | 11.07% | 12.05% | 10.10% | <0.001 |

After adjusting for different lag days, the temperature was still significantly negatively correlated with daily new cases when the temperature was below 20°C, and positively correlated with daily new cases when the temperature was above 20°C. When the temperature was below 20°C, the strongest effects (That is, the maximum percentage change of daily new cases per unit of meteorological variable) were observed at lag 014, with a 1 °C increase in temperature being associated with a 9.88% reduction in daily new cases. When the temperature was above 20°C, the strongest effects were observed at lag 01, with a 1 °C increase in temperature being associated with an 11.07% increase in daily new cases (Table 5 ).

Table 5.

The effects of a 1 °C increase in temperature on daily new cases of COVID-19 in different lag structures.

| Lag structure | Days lagged | Daily new cases |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature ≤20°C | Temperature >20 °C | ||

| single day lag | lag1 | −5.96%* | 10.23%* |

| lag3 | −6.66%* | 9.17%* | |

| lag7 | −7.42%* | 7.78%* | |

| lag14 | −7.52% | 6.33%* | |

| cumulative lag | lag01 | −5.45%* | 11.07%* |

| lag03 | −6.48%* | 11.01%* | |

| lag07 | −8.09%* | 11.00%* | |

| Lag014 | −9.88%* | 10.63%* | |

*: p < 0.05.

3.2.2.2. Relationship between relative humidity and COVID-19

The exposure-response curves in Fig. 2(b) revealed that the correlation between relative humidity and daily new cases of COVID-19 was non-linear (p < 0.001). The relationship was approximately linear in the range of <70% and became flat above 70%, indicating that the single threshold of the relative humidity effect on COVID-19 was 70%.

Based on results from GAMs, a piecewise linear regression was adapted with a threshold at a 70% to quantify the effect of relative humidity above and below the threshold. As showed in Table 6 , a 1% increase in relative humidity, the number of daily new cases decreased by 1.67% (95%CI: 1.40%–1.95%) when relative humidity was below 70%. When relative humidity was above 70%, the effect of temperature was not statistically significant (Table 6).

Table 6.

The effects of a 1% increase in relative humidity on daily new cases of COVID-19.

| Relative humidity (%) | Daily new cases |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | 95%CI |

P | ||

| Upper limit | Lower limit | |||

| ≤70 | −1.67% | −1.40% | −1.95% | <0.001 |

| >70 | 0.17% | 0.76% | −0.42% | 0.568 |

After adjusting for different lag days, relative humidity was still significantly negatively correlated with daily new cases when the relative humidity was below 70%. When relative humidity was below 70%, the strongest cumulative effects were observed at lag 014, with a 1 °C increase in relative humidity being associated with 2.28% reduction in daily new cases. When relative humidity was above 70%, the results showed that the correlation between relative humidity and new cases was not robust in different lag structures (Table 7 ).

Table 7.

The effects of a 1% increase in relative humidity on daily new cases of COVID-19 in different lag structures.

| Lag structure | Days lagged | Daily new cases |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative humidity≤70% | Relative humidity>70% | ||

| single day lag | lag1 | −1.68%* | −0.04% |

| lag3 | −1.43%* | −0.26% | |

| lag7 | −1.40%* | 0.54% | |

| lag14 | −1.05%* | 0.57% | |

| cumulative lag | lag01 | −1.61%* | 0.17% |

| lag03 | −1.98%* | −0.82%* | |

| lag07 | −2.20%* | −1.42%* | |

| lag014 | −2.28%* | −0.85%* | |

*: p < 0.05.

3.2.2.3. Relationship between wind speed and COVID-19

The exposure-response curves in Fig. 2(c) suggested that the correlation between wind speed and daily new cases of COVID-19 was non-linear (p < 0.001). Based on results from GAM, we conducted a piecewise linear analysis of wind speed with 7 m/s as the threshold. Table 8 shows the effect of wind speed at different layers on new daily cases after stratification. A 1 m/s increase in wind speed, the number of daily new cases decreased by 5.58% (95%CI: 3.46%–7.69%) when wind speed was below 7 m/s. When wind speed was above 7 m/s, there was no statistically significant relationship between wind speed and daily new cases.

Table 8.

The effects of a 1 m/s increase in wind speed on daily new cases of COVID-19.

| Wind speed(m/s) | Daily new cases |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | 95%CI |

P | ||

| Upper limit | Lower limit | |||

| ≤7 | −5.58% | −3.46% | −7.69% | <0.001 |

| >7 | 1.77% | 9.85% | −6.31% | 0.668 |

After adjusting for different lag days, the wind speed was still significantly negatively correlated with daily new cases when the wind speed was below 7 m/s. when the wind speed was above 7 m/s, the strongest cumulative effects were observed at lag 014, with a 1 m/s increase in wind speed being associated with 10.85% reduction in daily new cases. When wind speed was above 7 m/s, there was still no statistically significant relationship between wind speed and daily new cases (Table 9 ).

Table 9.

The effects of a 1 m/s increase in wind speed on daily new cases of COVID-19 in different lag structures.

| Lag structure | Days lagged | Daily new cases |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind speed≤7 m/s | Wind speed>7 m/s | ||

| single day lag | lag1 | −2.83%* | −3.78% |

| lag3 | −3.41%* | −4.71% | |

| lag7 | −3.90%* | 0.43% | |

| lag14 | −5.06%* | −5.83% | |

| cumulative lag | lag01 | −5.58%* | 1.77% |

| lag03 | −6.29%* | −4.20% | |

| lag07 | −9.54%* | −7.36% | |

| lag014 | −10.85%* | −2.65% | |

*: p < 0.05.

3.3. Sensitivity analysis

Taking into account the heterogeneous impact of climatic conditions on exposure events and the fact that some countries are experiencing a significantly higher rate of new cases due to factors other than meteorological factors, we excluded Chile, South Africa, Peru and Russia to fit our core GAM model to determine the relative stability of our empirical results. We also used a piecewise linear model to quantify the effect of this sensitivity analysis. Table 10 showed daily new cases percentage change (%) associated with each 1 unit increase in temperature, relative humidity and wind speed. The correlations found in this paper above remained robust.

Table 10.

Estimated changes with 95% confidence intervals in daily new cases percentage change (%) associated with each 1 unit increase in temperature, relative humidity and wind speed in 123 countries excluding Chile, South Africa, Peru and Russia.

| Daily new cases | β | 95%CI |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limit | Lower limit | ||||

| Temperature (°C) | ≤20 | −4.56% | 2.13% | −5.62% | <0.001 |

| >20 | 10.45% | 11.43% | 9.47% | <0.001 | |

| Relative humidity (%) | ≤70 | −1.46% | −1.22% | −1.70% | <0.001 |

| >70 | 0.50% | 1.32% | −0.32% | 0.231 | |

| Wind speed(m/s) | ≤7 | −6.39% | −4.28% | −8.49% | <0.001 |

| >7 | 1.89% | 10.15% | −6.37% | 0.654 | |

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is the global health crisis and the greatest challenge facing the world (Wu et al., 2020). Our findings explored the non-linear relationship between meteorological variables and daily new cases of COVID-19 by using a GAM. Our findings revealed that temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed were nonlinearly correlated with daily new cases.

Conclusions about the effect of meteorological conditions on the transmission of COVID-19 were still controversial. To date, several studies examining the effects of meteorological variables on COVID-19 transmission have explored the role of temperature. Some global or regional studies have reported a negative correlation between temperature and COVID-19(Sobral, Duarte, da Penha Sobral, Marinho and de Souza Melo, 2020) (Rouen et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020),)(L.Liu et al., 2017). Whereas Some studies observed the positive or insignificant relationships between temperature and the disease, without adjusting for other meteorological factors(Bashir et al., 2020; C.Liu, Wang, Liu, Sun and Peng, 2020a; Yao et al., 2020) (Pani et al., 2020),Some studies also put forward the non-linear relation between temperature and COVID-19(Prata et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020) (Hoang and Tran, 2020; Prata et al., 2020; Runkle et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). The literature of Prata et al.(Prata et al., 2020) showed that temperature was found temperatures had a negative linear relationship with the number of confirmed cases and the curve flattened at a threshold of 25.8 °C. There is no evidence supporting that the curve declined for temperatures above 25.8 °C. Research by Chien et al.(Chien and Chen, 2020) also shows that each meteorological factor and COVID-19 more likely have a nonlinear association rather than a linear association over the wide ranges of temperature, relative humidity, and precipitation observed. The overall impact of the average temperature on COVID-19 was found to peak at 68.45 °F (20.25°C) and decrease at higher degrees, though the overall relative risk percentage (RR %) reduction did not become significantly negative up to 85 °F (29.44°C). There are also data from China and South Korea that report a significant nonlinear association between temperature and the number of new cases confirmed daily. In particular, Xie et al.(Xie and Zhu, 2020) found that when the temperature was below 3°C, each 1°C increase in the number of confirmed cases per day increased by 4.86% (95% CI = 3.21–6.51). Hoang et al.(Hoang and Tran, 2020) found that the threshold was 8°C, with a 9% increase of COVID-19 confirmed cases when the temperature was below 8°C. Our results show that temperatures below 20°C were negatively correlated with COVID-19 transmission. The mechanism by which low temperature promotes virus transmission may be that temperature can affect virus transmission by affecting the stability of the virus or the innate immunity of humans(Biryukov et al., 2020; Chin et al., 2020). In this study, we found a positive effect on COVID-19 infection for higher temperatures above 20 °C. Perhaps the transmission of COVID-19 could fit higher temperatures. Further studies need to be conducted to discover new findings and determinants.

Humidity has been identified as one factor that influences seasonality of COVID-19, some previous studies had linked high incidence to low humidity(Bashir et al., 2020; Biktasheva, 2020). Low relative humidity promotes transmission by affecting the persistence of aerosol droplets in the air and reducing the ability of airway ciliated cells to remove virus particle. A previous study in US reported that here was a generally downward trend of RR % with the increase of minimum relative humidity; nonetheless, the trend reversed when the minimum relative humidity exceeded 91.42%. Our results showed that when relative humidity is lower than 70%, it is significantly negatively correlated with COVID-19 transmission, but when it is higher than 70%, the relationship between the two cannot be confirmed.

The wind is an important factor in the spread of infectious diseases and may modulate the dynamics of various pathogens and vectors(Ellwanger and Chies, 2018). A previous study suggested that wind speed is significantly negative correlated with COVID-19 cases in range from 3.60 to 5.70 m/s(Rendana, 2020). Previous literature suggested that high concentrations of low wind speeds, associated with air pollutants, may promote a longer permanence of the viral particles in the air, thus favoring the diffusion of SARS-CoV-2(Coccia, 2020). Negative correlation between COVID-19 and wind speed was also reported over Iran(Ahmadi et al., 2020) and Singapore(Pani et al., 2020). In this study, threshold was obtained at 7 m/s, as the wind speed increases, the number of daily new cases decreases when the wind speed was below 7 m/s. while there is no significant correlation between them when wind speed was above 7 m/s.

Compared with previous research, this research obtained and analyzed data for a longer time range from January 1, 2020, to August 8, 2020, in 127 countries. Research period of this paper includes three seasons of winter, autumn and summer in 108 countries in the northern hemisphere, and two seasons of autumn and winter in 19 countries in the southern hemisphere. It partly explained why outbreaks occur in some countries or regions during periods of high temperature and high humidity, as well as the conclusions drawn from studies and studies at different times and in different regions. The results suggested that COVID-19 may not go away on its own because of warmer weather or higher humidity. Our research results showed that temperature, relative humidity and wind speed were negatively correlated with the transmission of COVID-19 when the three factors were lower than 20°C, 70% and 7 m/s respectively.

As countries in the northern hemisphere over the 127 countries gradually enter the autumn and winter seasons, the temperature and relative humidity in most countries is gradually decreasing, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in some countries in the northern hemisphere may increase. At present, economic exchanges between these 127 countries are gradually returning to stability, and relevant agreements are progressing in an orderly manner. These countries have close contacts and are increasingly becoming a whole, so the deterioration of the epidemic situation in some countries is likely to spread to other countries, and some countries may even face a second wave of outbreaks on a large scale. The prevention and control of the epidemic situation in various countries, especially the prevention and control of imported cases, may face a more difficult situation.

The advantages of this study are as follows. Compared to previous studies, this paper included data from 127 countries in which COVID-19 cases had been reported over a longer period of time to analyze. In addition, in gauging the transmission and attributable cases of COVID-19 as induced by meteorological factors, we rely on the daily temperature, wind speed and relative humidity as well as the number of new cases of COVID-19 because of the incubation period. Both the observed meteorological factors and health indices have daily frequencies and as such inferences drawn along such path can eliminated the long-term trend of the COVID-19 epidemic and be used to guide the containment, risk analysis, features and structures of the spread of COVID-19.

There are also some limitations to this study. First, meteorological parameters were obtained from a single site, which may affect the statistical analysis. Secondly, due to the adjustment of diagnostic criteria in different countries and the difference of test coverage in different countries during the epidemic period, there will be a difference between the actual number of cases and the number of reported cases. Finally, ecological studies are insufficient to prove causation because of residual confounding of covariables such as population genetics, health infrastructure, peoples' obedience to social-distancing and social-isolation, and persons' immunity.

5. Conclusion

This study mainly aims to contribute the community research by investigating the association between COVID-19 and meteorological parameters over 127 countries by using statistical approaches. Our results indicated that temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed are nonlinearly correlated with daily new cases, and they may be negatively correlated with the daily new cases of COVID-19 over 127 countries when temperature, relative humidity and wind speed were below 20°C, 70% and 7 m/s respectively. Temperature (above 20°C) and relative humidity (above 70%) was positively correlated with daily new cases, but the latter correlation was not robust. Wind speed (above 7 m/s) was not statistically associated with the transmission of COVID-19. When using different hysteresis structures, the results except for relative humidity (above 70%) were still robust. The results of this research will be a useful supplement to help healthcare policymakers to understand the weather dependency of COVID-19 over these countries. Active measures must be taken to control the spread and further spread of COVID-19.

Availability of supporting data

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the website.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2020YFC0846300) and The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71934002).

Author contributions

Jie Yuan: Writing - original draft, Methodology, Software, Data curation. Yu Wu: Writing - review & editing. Wenzhan Jing -review & editing Visualization. Jue Liu: Supervision, Methodology. Min Du: Data curation, Investigation. Liangyu Kang :Data curation, Investigation. Min Liu: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition,Project administration, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Wei Li for guiding the use of the software.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110521.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ahmadi M., Sharifi A., Dorosti S., Jafarzadeh Ghoushchi S., Ghanbari N. Investigation of effective climatology parameters on COVID-19 outbreak in Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138705. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M.F., Ma B., Bilal, Komal B., Bashir M.A., Tan D. Correlation between climate indicators and COVID-19 pandemic in New York, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138835. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi P., Wang J., Hiller J.E. Weather: driving force behind the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome in China? Intern. Med. J. 2007;37(8):550–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biktasheva I.V. Role of a habitat's air humidity in Covid-19 mortality. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736:138763. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biryukov J., Boydston J.A., Dunning R.A., Yeager J.J., Wood S., Reese A.L. Increasing temperature and relative humidity accelerates inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces. mSphere. 2020;5(4) doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00441-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.H., Peiris J.S., Lam S.Y., Poon L.L., Yuen K.Y., Seto W.H. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv. Virol. 2011:734690. doi: 10.1155/2011/734690. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Tian E.K., He B., Tian L., Han R., Wang S. Overview of lethal human coronaviruses. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2020;5(1):89. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0190-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Yang X. Countries along the “Belt and Road” are being severely tested by the epidemic. Int. Finance. 2020;6:33–36. Z. Y. [Google Scholar]

- Chien L.C., Chen L.W. Meteorological impacts on the incidence of COVID-19 in the U.S. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00477-020-01835-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin A.W.H., Chu J.T.S., Perera M.R.A., Hui K.P.Y., Yen H.L., Chan M.C.W. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microb. 2020;1(1):e10. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. How do low wind speeds and high levels of air pollution support the spread of COVID-19? Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of, V The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5(4):536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici F., Peng R.D., Bell M.L., Pham L., McDermott A., Zeger S.L. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Jama. 2006;295(10):1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwanger J.H., Chies J.A.B. Wind: a neglected factor in the spread of infectious diseases. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(11):e475. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisman D. Seasonality of viral infections: mechanisms and unknowns. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18(10):946–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparrini A. Modeling exposure-lag-response associations with distributed lag non-linear models. Stat. Med. 2014;33(5):881–899. doi: 10.1002/sim.5963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthe S.S., Swain B., Patra S.S., Amte A. On the global trends and spread of the COVID-19 outbreak: preliminary assessment of the potential relation between location-specific temperature and UV index. Z. Gesundh. Wiss. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01279-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasell J., Mathieu E., Beltekian D., Macdonald B., Giattino C., Ortiz-Ospina E. A cross-country database of COVID-19 testing. Scientific Data. 2020;7(1):345. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-00688-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen T., Järvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T., Tran T.T.A. Ambient air pollution, meteorology, and COVID-19 infection in Korea. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodera S., Rashed E.A., Hirata A. Correlation between COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates in Japan and local population density, temperature, and absolute humidity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(15) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutter J.S., Spronken M.I., Fraaij P.L., Fouchier R.A., Herfst S. Transmission routes of respiratory viruses among humans. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2018;28:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K., Yee-Tak Fong D., Zhu B., Karlberg J. Environmental factors on the SARS epidemic: air temperature, passage of time and multiplicative effect of hospital infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 2006;134(2):223–230. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805005054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Wang X., Liu C., Sun Q., Peng W. Differentiating novel coronavirus pneumonia from general pneumonia based on machine learning. Biomed. Eng. Online. 2020;19(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s12938-020-00809-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zhou J., Yao J., Zhang X., Li L., Xu X. Impact of meteorological factors on the COVID-19 transmission: a multi-city study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;726:138513. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Hou X., Ren Z., Lowe R., Wang Y., Li R. Climate factors and the East Asian summer monsoon may drive large outbreaks of dengue in China. Environ. Res. 2020;183:109190. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Wei J., Li Y., Ooi A. Evaporation and dispersion of respiratory droplets from coughing. Indoor Air. 2017;27(1):179–190. doi: 10.1111/ina.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Arriaga F. The temperature and regional climate effects on communitarian COVID-19 contagion in Mexico throughout phase 1. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;735:139560. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National, Health, & Commission . 2020. New Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Plan. (Trial Eighth Edition) [Google Scholar]

- Neher R.A., Dyrdak R., Druelle V., Hodcroft E.B., Albert J. Potential impact of seasonal forcing on a SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2020;150:w20224. doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOAA . 2020. Global Summary of the Day.https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/search/data-search/global-summary-of-the-day [Google Scholar]

- Pani S.K., Lin N.H., RavindraBabu S. Association of COVID-19 pandemic with meteorological parameters over Singapore. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;740:140112. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paynter S. Humidity and respiratory virus transmission in tropical and temperate settings. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015;143(6):1110–1118. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814002702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R.D., Dominici F., Louis T.A. Model choice in time series studies of air pollution and mortality. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. 2006;169(2):179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Pica N., Bouvier N.M. Environmental factors affecting the transmission of respiratory viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2(1):90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portal B.a.R. 2019. A List of Countries that Have Signed Cooperation Documents with China to Jointly Build the "Belt and Road.https://www.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/xwzx/roll/77298.htm Retrieved 2 September 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- Prata D.N., Rodrigues W., Bermejo P.H. Temperature significantly changes COVID-19 transmission in (sub)tropical cities of Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138862. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H., Xiao S., Shi R., Ward M.P., Chen Y., Tu W. COVID-19 transmission in Mainland China is associated with temperature and humidity: a time-series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138778. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendana M. Impact of the wind conditions on COVID-19 pandemic: a new insight for direction of the spread of the virus. Urban Clim. 2020;34:100680. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouen A., Adda J., Roy O., Rogers E., Lévy P. COVID-19: relationship between atmospheric temperature and daily new cases growth rate. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020;148:e184. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runkle J.D., Sugg M.M., Leeper R.D., Rao Y., Matthews J.L., Rennie J.J. Short-term effects of specific humidity and temperature on COVID-19 morbidity in select US cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;740:140093. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şahin M. Impact of weather on COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138810. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P., Dong Y., Yan H., Zhao C., Li X., Liu W. Impact of temperature on the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138890. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit A.J., Fitchett J.M., Engelbrecht F.A., Scholes R.J., Dzhivhuho G., Sweijd N.A. Winter is coming: a southern hemisphere perspective of the environmental drivers of SARS-CoV-2 and the potential seasonality of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(16) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobral M.F.F., Duarte G.B., da Penha Sobral A.I.G., Marinho M.L.M., de Souza Melo A. Association between climate variables and global transmission oF SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138997. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmoudi K., Bellali H., Ben-Alaya N., Saez M., Malouche D., Chahed M.K. Modeling zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis incidence in central Tunisia from 2009-2015: forecasting models using climate variables as predictors. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2017;11(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Munster V.J. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(38) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.38.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Weekly Epidemiological Update and Weekly Operational Update.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports Retrieved 2 September 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. Health Topics/coronavirus.https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 Retrieved. from. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. WHO Director-General's Statement on IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-ihr-emergency-committee-on-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov 30 January 2020) Retrieved 2 September 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Jing W., Liu J., Ma Q., Yuan J., Wang Y. Effects of temperature and humidity on the daily new cases and new deaths of COVID-19 in 166 countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:139051. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Zhu Y. Association between ambient temperature and COVID-19 infection in 122 cities from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;724:138201. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Pan J., Liu Z., Meng X., Wang W., Kan H. No association of COVID-19 transmission with temperature or UV radiation in Chinese cities. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.00517-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Xue T., Jin X. Effects of meteorological conditions and air pollution on COVID-19 transmission: evidence from 219 Chinese cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;741:140244. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the website.