Abstract

Clinicians who treat children with neurodevelopmental disabilities may encounter infants with congenital Zika syndrome or those exposed to Zika virus (ZIKV), either in utero or postnatally, in their practice and may have questions about diagnosis, management, and prognosis. In this special report, we reviewed the current literature to provide a comprehensive understanding of the findings and needs of children exposed to ZIKV in utero and postnatally. The current literature is sparse, and thus, this review is preliminary. We found that infants and children exposed to ZIKV in utero have a variety of health and developmental outcomes that suggest a wide range of lifelong physical and developmental needs. Postnatal exposure does not seem to have significant long-lasting health or developmental effects. We provide a comprehensive examination of the current knowledge on health and developmental care needs in children exposed to Zika in utero and postnatally. This can serve as a guide for health care professionals on the management and public health implications of this newly recognized population.

Keywords: Zika, microcephaly, development, disability

Since 2016, Zika virus (ZIKV) has emerged as a global health threat because of its newly identified association with congenital microcephaly.1 ZIKV, named for the Zika forest in Uganda where it was originally identified in 1947, is a Flavivirus transmitted by mosquitoes.1,2 After it was identified, and for the remainder of the 20th century, infections in humans were primarily confined to Africa and Southeast Asia. During that time, ZIKV infection was thought to be fairly benign, with most cases being completely asymptomatic or manifesting as mild fever, rash, and conjunctivitis. However, in 2015, ZIKV emerged in the Americas, and thousands of cases of acute exanthematous illness were reported in Brazil; months later, a sudden and marked increase in reported cases of congenital microcephaly was noted and temporally associated with ZIKV transmission in the same regions during the first trimester of pregnancy in these women.3,4 The World Health Organization (WHO) declared ZIKV a global health emergency on February 1, 2016, and evidence to support a causal association between ZIKV and microcephaly was deemed sufficient in April 2016 and has continued to emerge.5,6 ZIKV is present in many areas of the world. Updated information on areas of ZIKV risk is located at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/zika-travel-information. In addition to transmission through a mosquito bite, ZIKV can be transmitted in the following ways: intrauterine/perinatal, sexual, laboratory exposure, and blood transfusion (probable).

In November 2016, WHO designated an end to the public health emergency and a shift to a long-term approach to answer the multitude of research questions that have emerged about this virus. Now, as the body of evidence builds regarding the pathophysiology of ZIKV and strategies for prevention, questions remain about the full spectrum of sequelae and the long-term implications of congenital Zika infection for individuals, families, and communities. Historical examples of other congenital infections, such as congenital rubella and congenital cytomegalovirus, suggest that microcephaly and the associated brain anomalies may only be the most severe manifestation of ZIKV’s effect on the developing brain. Furthermore, the more subtle neurodevelopmental disabilities, such as learning disabilities, may be identified later in life but nonetheless have significant implications for disability as these children reach adulthood.7

Congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) resulting in microcephaly and fetal brain disruption sequence is now well described. Currently, CZS is recognized as 5 structural anomalies that, while they individually may be shared with other congenital infections, collectively seem to be unique to CZS.8,9 These include (1) severe microcephaly with partially collapsed skull, (2) cortical thinning of the brain associated with abnormal gyral patterns and subcortical calcifications, (3) ocular anomalies, (4) congenital contractures, and (5) hypertonia.8 In contrast, researchers are currently working to explain the sequelae of prenatal ZIKV exposure in infants without overt anomalies and with normal head circumference at birth. As a generation of infants with prenatal ZIKV exposure begins to grow and develop, a broader spectrum of sequelae of this infection may emerge, presenting the possibility of thousands of children at risk of a broad spectrum of developmental concerns.

Clinicians who treat children with neurodevelopmental disabilities may encounter infants with CZS or those exposed to ZIKV, either in utero or postnatally, in their practice and may have several questions about diagnosis, management, and prognosis in such cases (Table 1). In this special report, we will review the current knowledge on special health care needs in prenatal Zika infection and CZS to guide clinicians and other allied health care professionals on the management and public health implications of this newly recognized population (Table 2). The current literature is sparse, and thus, this review is preliminary. It is important to note that the full spectrum of congenital effects of congenital ZIKV infection is not known at this time and that the long-term neurodevelopmental sequelae for these children are also not known.

Table 1.

Case Scenarios Relevant to ZIKV Likely to Be Encountered by Health Professionals Serving Children with Developmental Disabilities

| Case Scenario | Questions to Be Answered |

|---|---|

| 1. An infant presents to the clinic with known CZS | What is known about the developmental outcomes in these patients? What co-occurring conditions are important to screen or monitor for? What interventions are effective in this patient population? |

| 2. An infant presents to the clinic with a history of microcephaly or other anomalies similar to CZS and unknown etiology | Can this infant be tested for CZS? What other etiologies should I consider? |

| 3. An infant or child presents to the clinic with possible prenatal exposure to ZIKV or documented prenatal ZIKV infection but typical appearance at birth | Is this infant at risk of developmental disabilities such as cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder? How can one counsel the family on what to expect? Can prenatal exposure to ZIKV cause more subtle disability (e.g., ADHD and learning disability or language delay)? |

| 4. An infant or child presents to the clinic with postnatal exposure to ZIKV | Is this infant at risk of developmental disabilities? How can one counsel the family on what to expect? |

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CZS, congenital Zika syndrome; ZIKV, Zika virus.

Table 2.

What We Know and What We Do Not Know About the Consequences of Congenital ZIKV

| What We Know | What We Do Not Know | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall |

|

|

| Head growth |

|

|

| Vision |

|

|

| Hearing |

|

|

| Feeding/nutrition |

|

|

| Motor development |

|

|

| Language/cognitive development |

|

|

| Epilepsy |

|

|

| Hydrocephalus |

|

|

| Orthopedic |

|

|

| Behavior |

|

|

| Other co-occurring conditions |

|

|

| Family and social concerns |

|

|

ASD, atrial septal defect; CP, cerebral palsy; CZS, congenital Zika syndrome; EEG, electroencephalogram; VSD, ventricular septal defect; ZIKV, Zika virus.

NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES IN INFANTS WITH CONGENITAL ZIKA SYNDROME

Microcephaly and Congenital Brain Anomalies

Microcephaly in congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) is merely the outwardly visible manifestation of intracranial abnormalities. After birth, MRI, computed tomography, and transfontanellar ultrasound are used to better define the spectrum of brain anomalies in CZS. Most frequently seen are subcortical calcifications, increased fluid spaces (documented as ventriculomegaly, hydrocephalus, and enlarged extra-axial spaces), and abnormal structure and thickness of the cortex. The location of calcifications at the junction of the gray and white matter may differentiate CZS from other congenital infections (e.g., Cytomegalovirus infection, in which they are periventricular). Descriptions of the cerebral cortex in infants with CZS include polymicrogyria, pachygyria, simplified gyral pattern, and lissencephaly. Numerous other findings have also been described, including dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, hypo-myelination, cerebellar hypoplasia, brainstem hypoplasia, brainstem calcifications, reduced thickness of the spinal cord, subependymal cysts, vasculopathy, cerebral infarct, and cranial nerve enhancement.10-14

One study described follow-up imaging of 37 infants with CZS at age 1 year and noted that intracranial calcifications frequently diminished in number, size, or density, but this was not associated with clinical improvement.15

Vision

It was recognized fairly early that eye abnormalities are a common finding in CZS. Several series from Brazil report ophthalmologic abnormalities in approximately one-third to one-half of infants with microcephaly associated with CZS.16-18

Regarding visual function, several studies report impairment of 90% to 100% of infants with CZS and microcephaly.16,18 In 1 recent study of 119 infants at a mean age of 8 months from Pernambuco, Brazil, 80% had strabismus, 45% had nystagmus, 90% had visual acuity abnormalities, and 36% had abnormal visual fields.18 This same study also examined visual developmental milestones and found that although 88% of infants with CZS made eye contact at age 8 weeks, only 54% had a social smile at age 3 months, 27% had goal-directed reach at age 5 to 6 months, and only 27% regarded facial features at age 7 to 10 months.18 In those infants with significant structural abnormalities of the brain, it is still unclear how much of the visual impairment is attributed to ocular abnormalities versus abnormalities in the optic radiations, primary visual cortex, or cortical visual processing centers. It is also noted that follow-up ocular findings and visual function in this patient population have been limited to infants less than age 1 year. How the ophthalmologic and vision examination of these patients will evolve into childhood and adulthood is not yet understood.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends ophthalmologic screening by dilated fundoscopic examination during the first month of life for infants born to mothers with laboratory evidence of Zika virus (ZIKV) infection during pregnancy or for infants with abnormal clinical findings consistent with CZS.19

Eyeglasses have been shown to improve visual acuity in most infants with CZS and visual abnormalities, although vision was still below normal even with glasses.20 Refractive status may also change over time, and periodic reevaluation is recommended to update refraction. Other interventions for children with congenital visual impairment may be indicated, including patching and visual stimulation therapy. Strabismus surgery may also be recommended. The outcomes of these interventions in CZS have not yet been studied.

Hearing

Since ZIKV’s initial recognition as a congenital infection, infants with CZS have been considered at risk of congenital hearing impairment by drawing analogies from other congenital infections such as congenital CMV and congenital rubella. Because many infants with CZS have been followed over the first year of life with serial hearing screens, the frequency of hearing impairment in infants with prenatal ZIKV infection is clearer.

In a CDC report of 70 infants from Pernambuco, Brazil, up to age 10 months with microcephaly and confirmed evidence of ZIKV infection, only 10% had confirmed hearing impairment (29% conductive and 71% sensorineural) by auditory brainstem response (ABR) testing.21 Hearing impairment was not associated with a particular trimester of maternal infection or degree of microcephaly. In contrast, 68% of 19 children with CZS aged 19 to 24 months in 1 study had evidence of functional hearing impairment on clinical neurological examination.22 These studies vary in their approach to discussing hearing impairment, the first through results of an ABR and the second from clinical response to sound, which might explain the variability in results. Further studies are needed to understand the impact of congenital ZIKV infection on hearing.

The CDC currently recommends that all newborns with evidence of prenatal ZIKV infection or findings suggestive of CZS receive a hearing screen by automated ABR within the first month of life. In infants who pass the newborn screen, there is thus far no evidence suggesting that delayed-onset hearing loss occurs after the neonatal period. Therefore, the early recommendation for a diagnostic ABR in those who pass initial newborn screen is no longer in place.19 The effect of interventions such as amplification or cochlear implants for hearing impairment in CZS is not yet studied.

Feeding/Nutrition

Growth abnormalities associated with CZS may occur both prenatally and postnatally. Intrauterine growth restriction is a common finding along with microcephaly and can be identified on prenatal ultrasound.23 In a study of 48 infants with CZS from Brazil, 43% had a birth length more than 2 SDs below the mean, and 20% had a birth weight more than 2 SDs below the mean. During follow-up of these infants through a maximum of age 8 months, growth parameters continued to decline, with z-scores decreasing by 0.16 and 0.08 per month in length and weight, respectively.24 A second study of 25 infants with CZS in Brazil emphasized that although these infants grew in weight, length, and head circumference at 3 months of follow-up, percentiles relative to the normative population remained stable.25 Finally, in a group of infants followed up during the second year of life, 3 of 19 (16%) had weights more than 2 SDs below the mean for age.22

Although many infants with CZS feed independently at birth,17 dysphagia and difficulty feeding have been described in CZS and are likely secondary to neurological motor dysfunction. The long-term implications for nutrition in this population are poorly understood. Several case series report the frequency of dysphagia in CZS to be 14% to 77%.15,24,26 One report by de Carvalho Leal et al.27 described 9 infants with CZS and dysphagia in detail. All infants had abnormalities in the oral phase, and 8 infants had delays in the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, increasing the risk of aspiration with feeds. Notably, onset of dysphagia was after age 3 months in 8 of the 9 infants.27 Although many infants with CZS may require feeding supplementation by nasogastric or gastrostomy tubes for either failure to thrive or dysphagia, the impact of this intervention on their growth trajectories has yet to be studied, and whether growth delays are nutritional or constitutional has yet to be understood.

Motor Development

Thus far, motor impairment has been reported as a major feature of CZS, although the degree of impairment and phenotype may vary.8,28 Hypertonia is most frequently described as early as in the first month of life (37%-100%), but hypotonia may also be seen.23,24,26,29,30 Along with increased tone, hyperreflexia (17%-20%), abnormal posturing (21%-43%), and tremors (11%) are also described. Motor examination may also be difficult to assess in infants with arthrogryposis or other congenital contractures. In those infants with longer follow-up during the first year of life, persistence of reflexes including asymmetric tonic neck reflex is also noted, and the motor phenotype is more clearly described with elements of both spasticity and dystonia.24,26,30 Several series also report infants with unilateral or bilateral hemiparesis.23,26

In the longest developmental follow-up study to date, Satterfield-Nash et al.22 used the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination and reported severe motor impairment in 15 infants at age 19 to 24 months, 14 of whom had findings consistent with cerebral palsy. Notably, in these children, severe outcomes including dysphagia, motor impairment, vision and hearing deficits, and epilepsy tended to co-occur. Based on reports of their early developmental trajectories, it is likely that as they age, many children with CZS will never become ambulatory or will have other disabling motor impairments such as dyspraxia that impair gait or agility.

In summary, the reports above collectively describe static motor impairment in CZS consistent with a mixed clinical picture of both pyramidal and extrapyramidal cerebral palsy.

Language/Cognitive Development

Given that CZS has only recently been described in the last 3 years and many major milestones for language and cognition occur after the first year of life, follow-up on this realm of development in affected infants has been limited. However, given the severity of brain anomalies in many of these patients and the frequency of hearing impairment and motor impairment, which may further limit language development, the developmental trajectories in these infants are likely to be significantly delayed. In 1 investigation involving limited follow-up of 1 series of 19 infants with CZS aged 19 to 24 months, researchers administered the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Third Edition (ASQ-3), and found that all affected infants were nonverbal and scored below an age equivalent of 6 months, indicating severe global developmental delay.22,31 Based on this and other qualitative reports, it is likely that infants with CZS will frequently be left with severe to profound intellectual disability. It is still unknown how much of the delay in these infants may be attributed to hearing and motor impairment and whether interventions to improve hearing or communication may also facilitate achievement of cognitive milestones. Future studies will better elucidate their developmental potential.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is common in children with CZS, occurring in approximately 48% to 58% of affected infants in the first year of life.22,24,25,28 Seizures are frequently intractable, and multiple antiepileptic drugs are often required.24,25 In a series of 27 infants with electroencephalography (EEG), 48% had nonepileptiform abnormal activity, 30% had focal epileptiform activity, and 22% had multifocal epileptiform activity.24 Another series identified hypsarrhythmia in 30% of infants with CZS with similar rates of abnormalities on EEG.32

Hydrocephalus

Although ex vacuo hydrocephalus or ventriculomegaly is well recognized as a major finding in CZS, likely secondary to atrophy of brain tissue, hypertensive hydrocephalus may also occur. Of 115 infants with CZS followed at 1 center, 21 (18%) had worsening ventricular enlargement on neuroimaging, and 6 of these had symptoms of neurologic decline, including worsening seizures, drowsiness, or developmental regression.33 All 6 patients received ventriculoperitoneal shunting by neurosurgery and subsequently showed improvement in seizures, developmental milestones, and spasticity.33 Therefore, in children with CZS who present with acute or subacute neurologic decline from baseline, neurosurgical consultation may be indicated.

Orthopedic

Congenital orthopedic anomalies, frequently associated with fetal motor impairment, have been well described in CZS and are considered to be one of the major features of this syndrome because they are rarely seen in other congenital infections.8,12 A report of 83 infants with CZS from 10 sites in Brazil described a spectrum of orthopedic anomalies ranging from distal digit contractures in 20% to feet malposition in 16% and generalized arthrogryposis in 10%.30 Other smaller studies have echoed these findings, with isolated clubfoot occurring in 4% to 14% and arthrogryposis occurring in 6% to 11%.8,24 All these cases have been associated with malformations in cortical development on brain imaging and are therefore presumed to be neurogenic in origin rather than a primary abnormality of the joints.12,13 Infants with severe arthrogryposis may also have abnormalities in the brainstem or spinal cord.13 In 1 series of 7 infants with CZS and arthrogryposis, 6 infants had all 4 limbs affected, and 1 infant was affected only in the lower extremities.12 Congenital hip dislocation is also frequently reported in infants with CZS and arthrogryposis.8

In contrast, orthopedic problems secondary to motor impairment that frequently occur in children with cerebral palsy have not yet been described in CZS, possibly because of the fact that this is a newly recognized disorder and affected infants are still fairly young. However, based on our understanding of other developmental disabilities affecting children with severe motor impairment, children with CZS are likely to be at risk of osteopenia, scoliosis, hip dislocation, and acquired contractures as they age.

Behavior

Information on behavioral problems in CZS is limited because of short follow-up times in most reports. However, several case series reported profound irritability during infancy.15,24,26 One study of 48 infants from Brazil reported irritability in 85% of cases in the first year of life.24 In 1 report, irritability improved after age 4 months.26 Sleep disorders are also common in CZS and may occur in one-third to one-half of patients during the first 2 years of life.22,34 Future long-term follow-up studies will reveal the behavioral profiles in these patients in more detail. Given the profound degree of developmental delay described earlier, it is possible that children with CZS may be prone to behavioral problems also seen in other patients with profound intellectual disability, including agitation or self-injurious behavior.

Other Co-occurring Conditions

Several other co-occurring health conditions have been reported in children with CZS, which have implications for their long-term health care needs. However, further investigation is still needed, beyond case reports, to determine whether these are true associations with congenital Zika infection.

Congenital heart defects have been reported in CZS. In a report of 103 infants with CZS from Recife, Brazil, transthoracic echocardiogram revealed congenital heart disease in 14 infants (14%). Defects included atrial septal defects and ventricular septal defects.35 Another study of 120 children from Rio de Janeiro reported a similar spectrum of congenital heart defects in 11% of infants with confirmed prenatal ZIKV infection.36 Of note, many infants also had minimal patent ductus arteriosus and persistent foramen ovale, which were considered normal. Future case-control studies will clarify whether this risk is increased over that of the general population.

Neurogenic bladder has also been reported in CZS with a series of 22 infants identified at 1 center.37 All the infants had high-risk urodynamic patterns which, if untreated, may lead to infection and renal damage, presenting a serious comorbidity for these children.37

Other co-occurring findings reported include cleft lip and palate.24 Diaphragm paralysis identified at birth was reported in 3 infants with CZS, all of whom developed progressive respiratory failure and died within the first 3 months of life.17

Family and Social Concerns

Although the family and social concerns for those affected by CZS may vary across countries, geographies, and cultures, several emerging themes are important to consider. It is well recognized that families of children with complex neurodevelopmental disabilities are at risk of increased emotional stress, financial strain, social isolation, and adverse mental health outcomes.38 There is also potential for Zika-related stigma depending on the community’s comfort and understanding of the disease.38 Data are limited thus far on the social and emotional consequences of CZS on affected families, but a small case series from Aracaju, Brazil, showed that mothers of children with CZS had high levels of anxiety and low quality of life during the first year of their children’s lives.39

From a public health perspective, particularly in South America, there is evidence that low-income families may be disproportionately affected by CZS because of existing health care disparities and poor access to reproductive health services.40,41 These disparities are likely to be compounded by the increased health care needs of children with CZS and have the potential to put strain on public health services in regions that are affected. For example, in 2016, there was an 8-fold increase in the number of children eligible for benefits for people with disabilities in Brazil.42

Death

Many case series mention death of severely affected infants in the first days to months of life, and several case series report on pathology findings among infants who have died shortly after birth.43,44 In a review of the 2013 to 2014 ZIKV epidemic in French Polynesia, 2 of the 8 cases that were carried to term had brainstem dysfunction and died within the first few months of life.45 One study of 27 infants with CZS reported a fatality rate of 7% in the first 3 months of life.25

Because laboratory testing has presented challenges in understanding the extent to which babies have been exposed to ZIKV in utero, it is difficult to estimate the frequency of pregnancy losses and infant deaths that could be attributed to congenital Zika infection. An analysis using epidemiologic reports from the Brazil Ministry of Health from 2015 to 2016 estimated the case fatality rate to be 3% to 19% for fetal and neonatal deaths associated with neurologic abnormalities suspected to be caused by congenital Zika infection.46

DIAGNOSIS OF CONGENITAL ZIKA SYNDROME AND ASSOCIATED NEURODEVELOPMENTAL SEQUELAE

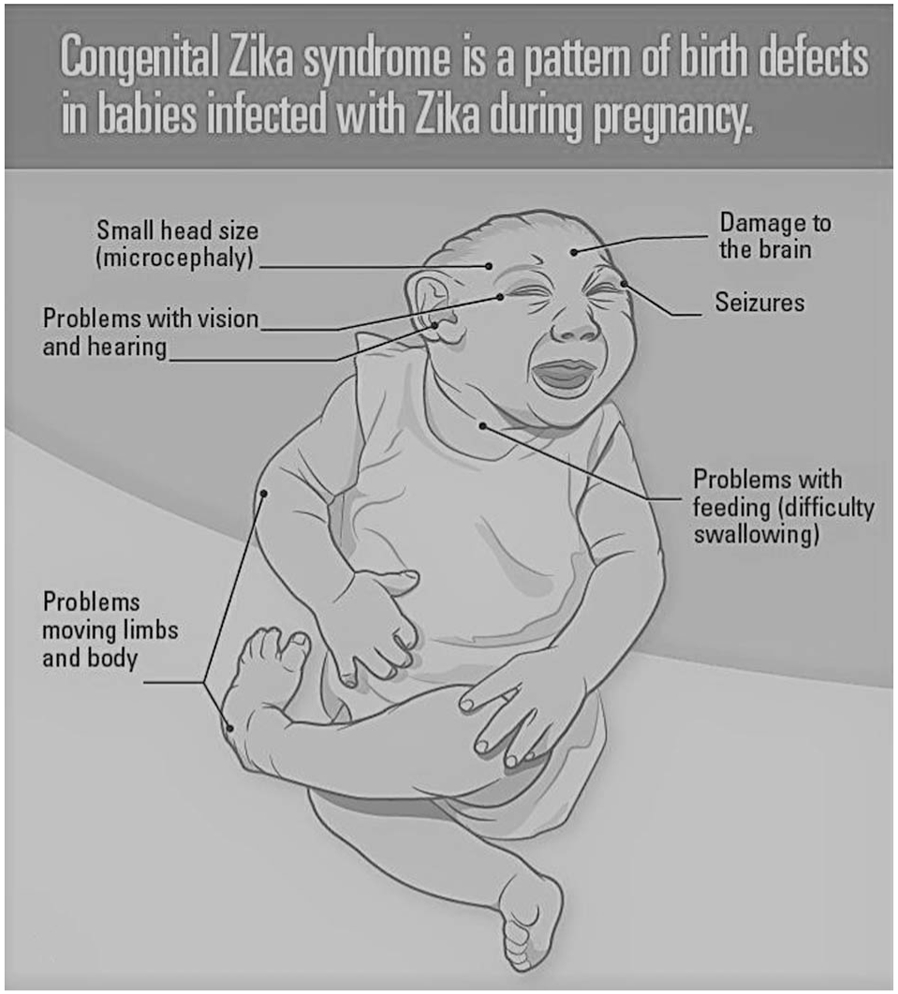

It is also important to note in the context of this article that interpretation of Zika virus (ZIKV) laboratory test results can be challenging because of cross-reactivity with other common flaviviruses, such as dengue virus. False positives and false negatives do occur. Thus, congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) is primarily a clinical diagnosis. A clinician must consider history of, or risk of maternal infection/exposure (i.e., living in or travel to endemic areas), clinical characteristics (including the 5 structural anomalies displayed in Fig. 1), and laboratory testing in the infant (including evaluation for ZIKV RNA in infant serum and urine and ZIKV IgM antibodies in serum, preferably in the first few days of life).

Figure 1.

Congenital Zika syndrome is a pattern of birth defects in babies infected with Zika during pregnancy.

Both ZIKV RNA and antibody testing are most likely to be positive in the first few days of life; however, testing in older infants can be helpful in determining etiology for neurodevelopmental findings attributed to congenital ZIKV infection. In addition, although positive testing in the infant is helpful in confirming the diagnosis, negative testing does not rule out congenital ZIKV as a cause. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance for laboratory testing is regularly updated as laboratory testing is refined.19

If an infant has microcephaly at birth without the other typical features of CZS or develops microcephaly in the first few months, one should consider Zika as an etiologic cause. In addition to further inquiry into maternal history and laboratory testing, the clinician should perform evaluations that assess for associated neurodevelopmental sequelae including neuroimaging, dilated eye examination, and hearing screening using an auditory brainstem response. Updated information on areas of ZIKV risk is located at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/zika-travel-information.

DEVELOPMENT IN INFANTS WITH CONGENITAL ZIKA EXPOSURE WHO HAVE A TYPICAL APPEARANCE AT BIRTH

Most newborns born to mothers who have positive laboratory tests for Zika virus (ZIKV) infection during pregnancy have a typical appearance at birth. Results of laboratory testing have proved challenging to interpret, sometimes resulting in a positive test in the mother, followed by a negative test in the infant. Therefore, it is possible that there are both infants who were thought to have ZIKV infection who are actually not infected and also mothers and/or infants who test negative who actually do have ZIKV infection. These test results could also be consistent with the fact that not all ZIKV infections during pregnancy result in congenital infection.

Despite this confusion that laboratory testing presents, case series have reported isolated brain anomalies or eye anomalies in infants with otherwise typical examinations, but this represents the minority of cases.47,48 For this reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends an eye examination and head ultrasound in the first month of life, in addition to standard newborn screens, for infants with suspected congenital ZIKV exposure. However, it is important to keep in mind that this evaluation may not be available to patients in different geographical settings.

In a series of 112 infants born to mothers with confirmed ZIKV infection during pregnancy in Brazil, approximately 20% of all infants had abnormalities on ophthalmic examination, including optic nerve and retinal abnormalities. Most affected infants were exposed during the first trimester of pregnancy.47 Ten of the 24 cases occurred in the absence of microcephaly, and 8 had normal brain imaging, emphasizing that ophthalmic abnormalities may occur as the primary or only manifestation of congenital Zika infection.47 Similarly, another study found that chorioretinal abnormalities may be identified in approximately one-quarter of infants with congenital ZIKV infection despite normal head circumference at birth and good visual interaction in the first several months of life.26

In addition, there have been reports of children who appear typical at birth and who then develop postnatal microcephaly. Van der Linden et al.26 describe a series of 13 infants with normal head circumference at birth who subsequently developed microcephaly. In this series, at age 5 to 12 months, all had hypertonia, 92% had dystonic movements and extrapyramidal signs, 70% had no voluntary hand movement, and 38% had poor head control.

Clinicians providing preventive pediatric care to children who have known congenital ZIKV exposure and typical appearance at birth and who do not have findings on head ultrasound or ophthalmologic examination should be aware that there may be late effects and may need to pursue further diagnostic steps, if clinically indicated. Failure to meet normal growth or developmental milestones should prompt further diagnostic evaluation. In particular, clinicians should pay careful attention to head circumference growth over time to assess for postnatal microcephaly and possible associated brain anomalies.26

Large prospective studies are currently underway to investigate whether infants who meet growth and developmental milestones during the first year of life are at risk of more subtle developmental disability later in life. The protective or risk factors determining whether a fetus exposed to ZIKV will go on to develop congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) are not yet understood. Twin studies highlight the need for understanding the epigenetic phenomenon, which may determine outcome. Two cases were reported of twin pregnancies with prenatal exposure to ZIKV in which 1 fetus was affected by CZS and 1 fetus had a typical experience at birth and at ages 7 and 10 months.49 These cases represent an important example that not all pregnancies exposed to ZIKV will result in CZS or developmental disability, and both practitioners and families should be educated on this as well.

POSTNATAL ZIKA VIRUS INFECTION IN CHILDREN

Postnatal Zika virus (ZIKV) infection is generally considered benign in children, and symptomatic infection with rash, fever, or conjunctivitis is rarely associated with neurologic sequelae. In a retrospective study of more than 18,000 cases of symptomatic ZIKV infection in Colombia, only 3.4% of children were hospitalized, and 0.5% had neurologic involvement, primarily Guillain-Barre syndrome.50 Cases of encephalitis, myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) have also been described, with 1 case of ADEM in a 14-year-old child.51,52

Although breast milk may contain ZIKV, there have been no adverse outcomes reported of infants with ZIKV infection resulting from breastfeeding.53,54 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance suggests the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risks.19

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF CONGENITAL ZIKA SYNDROME

Although congenital Zika syndrome is being increasingly recognized, it is also important to consider other potential etiologies for microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, or other congenital brain anomalies in these patients. If not already done during the neonatal period, clinicians should also consider other congenital infections, including the most common “TORCH” infections (toxoplasmosis, rubella, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella) and genetic etiologies. Common genetic syndromes that may mimic congenital infection include Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome, Cockayne syndrome, OCLN mutations, COL41A mutations, and Krabbe disease.55,56 Frequently, clinical manifestations are similar between congenital infections and genetic syndromes; therefore, in the absence of a clear history of infection during pregnancy, consultation with a specialist in genetics or neurogenetics is recommended.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Is Congenital Zika Syndrome Going Away?

In Central and South America, cases of Zika virus (ZIKV) and associated birth defects dramatically declined over 2016 and 2017. Population exposure and herd immunity may be responsible, but the future of ZIKV as a relevant infection is still unknown. The duration of protective immunity against ZIKV, although suspected to be long lasting, remains to be definitively understood. ZIKV vaccine development is underway and may be an important preventive measure for women of childbearing age in the future.

Impact

With thousands of infants affected by congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) in South America and beyond, we recognize the vast global economic and social impact of developmental disabilities. Supporting individuals with developmental disabilities requires a complex multidisciplinary health care system. In many communities worldwide, an expansion of programs will be needed to sufficiently accommodate the potential increase in individuals with developmental disabilities. In the United States, in contrast, it is possible that CZS will occur sporadically and primarily because of travel to areas endemic to ZIKV.57 Considering the multiple complex needs of these children, it may be necessary for countries to build health care infrastructure to accommodate a multidisciplinary approach to address the complex needs of these children affected by congenital ZIKV. Building these systems has added benefit for many other children with complex needs who do not have a history of congenital ZIKV.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IML, et al. Possible association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly: Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dick GW, Kitchen SF, Haddow AJ. Zika virus I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46:509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleber de Oliveira W, Cortez-Escalante J, De Oliveira WT, et al. Increase in reported prevalence of microcephaly in infants born to women living in areas with confirmed Zika virus transmission during the first trimester of pregnancy: Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paploski IA, Prates AP, Cardoso CW, et al. Time lags between exanthematous illness attributed to Zika virus, Guillain-Barre Syndrome, and microcephaly, Salvador, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1438–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Araújo TVB, Ximenes RAA, Miranda-Filho DB, et al. Association between microcephaly, Zika virus infection, and other risk factors in Brazil: final report of a case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:328–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krow-Lucal ER, Regina de Andrade M, Nunes Abath Cananéa J, et al. Association and birth prevalence of microcephaly attributable to Zika virus infection among infants in Paraíba, Brazil, in 2015–16: a case-control study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2:205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lombardi G, Garofoli F, Stronati M. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: treatment, sequelae and follow-up. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(suppl 3):45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore CA, Staples JE, Dobyns WB, et al. Characterizing the pattern of anomalies in congenital Zika syndrome for pediatric clinicians. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:288–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cugola FR, Fernandes IR, Russo FB, et al. The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature. 2016; 534:267–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazin AN, Poretti A, Di Cavalcanti Souza Cruz D, et al. Computed tomographic findings in microcephaly associated with Zika virus. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2193–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soares de Souza A, Moraes Dias C, Braga FD, et al. Fetal infection by Zika virus in the third trimester: report of 2 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:1622–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Linden V, Filho EL, Lins OG, et al. Congenital Zika syndrome with arthrogryposis: retrospective case series study. BMJ. 2016;354:i3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aragao MFVV, Brainer-Lima AM, Holanda AC, et al. Spectrum of spinal cord, spinal root, and brain MRI abnormalities in congenital Zika syndrome with and without arthrogryposis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:1045–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulkey SB, Vezina G, Bulas DI, et al. Neuroimaging findings in normocephalic newborns with intrauterine Zika virus exposure. Pediatr Neurol. 2018;78:75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petribu NCL, de Lima Petribu NC, de Fatima Vasco Aragao M, et al. Follow-up brain imaging of 37 children with cngenital Zika syndrome: case series study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verçosa I, Carneiro P, Verçosa R, et al. The visual system in infants with microcephaly related to presumed congenital Zika syndrome. JAAPOS. 2017;21:300–304.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meneses JDA, Ishigami AC, de Mello LM, et al. Lessons learned at the epicenter of Brazil’s congenital Zika epidemic: evidence from 87 confirmed cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1302–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ventura LO, Ventura CV, Dias NC, et al. Visual impairment evaluation in 119 children with congenital Zika syndrome. J AAPOS. 2018;22:218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adebanjo T, Godfred-Cato S, Viens L, et al. Update: interim guidance for the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection—United States, October 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1089–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ventura LO, Lawrence L, Ventura CV, et al. Response to correction of refractive errors and hypoaccommodation in children with congenital Zika syndrome. J AAPOS. 2017;21:480–e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leal MC, Muniz LF, Ferreira TSA, et al. Hearing loss in infants with microcephaly and evidence of congenital Zika virus infection—Brazil, November 2015–May 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:917–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satterfield-Nash A, Kotzky K, Allen J, et al. Health and development at age 19–24 months of 19 children who were born with microcephaly and laboratory evidence of congenital Zika virus infection during the 2015 Zika virus outbreak—Brazil, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1347–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brasil P, Pereira JP Jr, Moreira ME, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2321–2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moura da Silva AA, Ganz JSS, Sousa PD, et al. Early growth and neurologic outcomes of infants with probable congenital Zika virus syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1953–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliveira-Filho J, Felzemburgh R, Costa F, et al. Seizures as a complication of congenital Zika syndrome in early infancy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:1860–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Linden V, Pessoa A, Dobyns W, et al. Description of 13 infants born during October 2015-January 2016 with congenital Zika virus infection without microcephaly at birth—Brazil. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1343–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Carvalho Leal M, van der Linden V, Bezerra TP, et al. Characteristics of dysphagia in infants with microcephaly caused by congenital Zika virus infection, Brazil, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1253–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pessoa A, van der Linden V, Yeargin-Allsopp M, et al. Motor abnormalities and epilepsy in infants and children with evidence of congenital Zika virus infection. Pediatrics. 2018;141(suppl 2): S167–S179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pacheco O, Beltrán M, Nelson CA, et al. Zika virus disease in Colombia: preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2016. [epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1604037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Del Campo M, Feitosa IM, Ribeiro EM, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of congenital Zika syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2017; 173:841–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alves LV, Paredes CE, Silva GC, et al. Neurodevelopment of 24 children born in Brazil with congenital Zika syndrome in 2015: a case series study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mello MDCG, Miranda-Filho DB, van der Linden V, et al. Sleep EEG patterns in infants with congenital Zika virus syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128:204–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jucá E, Pessoa A, Ribeiro E, et al. Hydrocephalus associated to congenital Zika syndrome: does shunting improve clinical features? Childs Nerv Syst. 2018;34:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinato L, Ribeiro EM, Leite RFP, et al. Sleep findings in Brazilian children with congenital Zika syndrome. Sleep. 2018;41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cavalcanti DD, Alves LV, Furtado GJ, et al. Echocardiographic findings in infants with presumed congenital Zika syndrome: retrospective case series study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orofino DHG, Passos SRL, de Oliveira RVC, et al. Cardiac findings in infants with in utero exposure to Zika virus: a cross sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa Monteiro LM, Cruz GNO, Fontes JM, et al. Neurogenic bladder findings in patients with congenital Zika syndrome: a novel condition. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailey DB Jr, Ventura LO. The likely impact of congenital Zika syndrome on families: considerations for family supports and services. Pediatrics. 2018;141(suppl 2):S180–S187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dos Santos Oliveira SJG, Dos Reis CL, Cipolotti R, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in mothers of newborns with microcephaly and presumed congenital Zika virus infection:a follow-up study during the first year after birth. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20:473–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gurgel D, Gumieri S, Bevilacqua BG, et al. Zika virus infection in Brazil and human rights obligations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017; 136:105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cook CT, Greene SK, Baumgartner J, et al. Disparities in Zika virus testing and incidence among women of reproductive age: New York City, 2016. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;24:533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pereira ÉL, Bezerra JC, Brant JL, et al. Perfil da demanda e dos Benefícios de Prestação Continuada (BPC) concedidos a crianças com diagnóstico de microcefalia no Brasil [in Portuguese]. Cien Saude Colet. 2017;22:3557–3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martines RB, Bhatnagar J, de Oliveira Ramos AM, et al. Pathology of congenital Zika syndrome in Brazil: a case series. Lancet. 2016;388: 898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chimelli L, Melo ASO, Avvad-Portari E, et al. The spectrum of neuropathological changes associated with congenital Zika virus infection. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133:983–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Besnard M, Eyrolle-Guignot D, Guillemette-Artur P, et al. Congenital cerebral malformations and dysfunction in fetuses and newborns following the 2013 to 2014 Zika virus epidemic in French Polynesia. Euro Surveill. 2016;21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cunha AJ, de Magalhães-Barbosa MC, Lima-Setta F, et al. Microcephaly case fatality rate associated with Zika virus infection in Brazil: current estimates. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36:528–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zin AA, Tsui I, Rossetto J, et al. Screening criteria for ophthalmic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:847–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aragao MFVV, Holanda AC, Brainer-Lima AM, et al. Nonmicrocephalic infants with Congenital Zika Syndrome suspected only after neuroimaging evaluation compared with those with microcephaly at birth and postnatally: how large is the Zika virus “iceberg”? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:1427–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Linden V, van der Linden Junior H, de Carvalho Leal M, et al. Discordant clinical outcomes of congenital Zika virus infection in twin pregnancies. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017;75:381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tolosa N, Tinker SC, Pacheco O, et al. Zika virus disease in children in Colombia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2017;31:537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brito Ferreira ML, Ferreira MLB, Henriques-Souza A, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and encephalitis associated with Zika virus infection in Brazil: detection of viral RNA and isolation of virus during late iInfection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:1405–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zare Mehrjardi M, Carteaux G, Poretti A, et al. Neuroimaging findings of postnatally acquired Zika virus infection: a pictorial essay. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35:341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blohm GM, Lednicky JA, Márquez M, et al. Evidence for mother-to-child transmission of Zika virus through breast milk. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1120–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Colt S, Garcia-Casal MN, Peña-Rosas JP, et al. Transmission of Zika virus through breast milk and other breastfeeding-related bodily-fluids: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11: e0005528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanchis A, Cerveró L, Bataller A, et al. Genetic syndromes mimic congenital infections. J Pediatr. 2005;146:701–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Livingston JH, Stivaros S, Warren D, et al. Intracranial calcification in childhood: a review of aetiologies and recognizable phenotypes. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56:612–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crow A, Clark S, Bloch D, et al. Surveillance for mosquitoborne transmission of Zika virus, New York city, NY, USA, 2016. Emerging Infect Dis. 2018;24:827–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]